Food insecurity, a lack of reliable access to a sufficient quantity of affordable, nutritious food, impacts over one-eighth of American households, with highest rates among households with incomes below the federal poverty level( 1 ). Food insecurity is associated with poor dietary quality and elevated disease risks( Reference Hanson and Connor 2 , Reference Laraia 3 ). Food banks in the USA typically operate as warehouses that store a large quantity and variety of food items to be distributed by smaller front-line agencies, called food pantries, which directly serve the end users free of charge. Food banks and food pantries in the USA distribute free grocery items to over 46·5 million Americans in need annually( Reference Rochester, Nanney and Story 4 , 5 ). Estimations of food insecurity among pantry clients in the USA range from 50 to 84%( 5 – Reference Robaina and Martin 7 ). Food pantries are often used to augment the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits( Reference Robaina and Martin 7 , Reference Bhattarai, Duffy and Raymond 8 ). However, some clients use food pantries as their primary or sole food source, partially due to SNAP ineligibility( Reference Dave, Thompson and Svendsen-Sanchez 9 ). Food pantries play a critical role in addressing the needs of Americans at high risk of food insecurity( 10 ).

Besides emergency food provision, food pantries may serve as a natural setting and focal point where additional services can be delivered to improve the diet and health status of the highly vulnerable client population. Previous reviews on food pantries largely focused on cross-sectional studies that assessed the nutritional values of foods provided, service types and quality, and client characteristics (e.g. food security status, dietary intake, malnutrition status, health or disease status, and frequencies or reasons for food pantry use)( Reference Bazerghi, McKay and Dunn 6 , Reference Simmet, Depa and Tinnemann 11 , Reference Simmet, Depa and Tinnemann 12 ). One prospective review intends to survey outcomes of disease prevention and management interventions in food pantries, but the review does not assess health behaviour (e.g. food choice) and results have yet to be reported( Reference Long, Rowland and Steelman 13 ). The purpose of the present study was to systematically review and synthesize scientific evidence regarding the effectiveness of food pantry-based interventions on diet-related outcomes in the USA. We focused on food pantries in the USA because the types and ways of operation of food banks and pantries differ substantially across countries, and they are also subject to different government regulations and serve diverse populations.

Methods

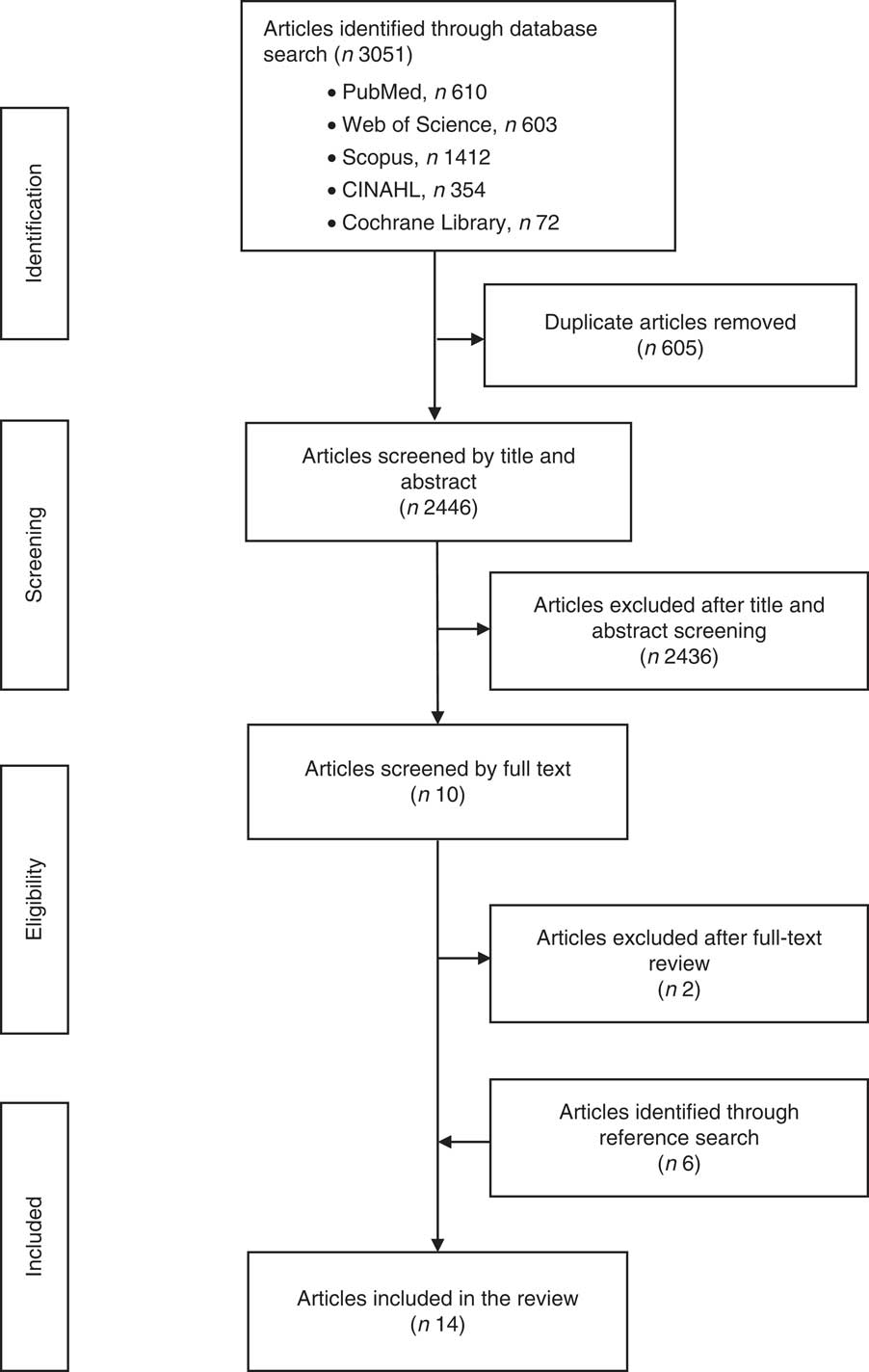

The systematic review was reported in accordance with the PRIMSA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement( Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff 14 ). Analysis was conducted in May 2018.

Data sources

A keyword search was performed in five electronic bibliographic databases: (i) PubMed; (ii) Web of Science; (iii) Scopus; (iv) Cochrane Library; and (v) Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). The search algorithm included all the following keywords: ‘food pantry’, ‘food pantries’, ‘food bank’, ‘food banks’, ‘food shelf’, ‘food shelves’, ‘food cupboard’, ‘food cupboards’ and ‘food assistance’. The MeSH (medical subject heading) term ‘food assistance’ was included in the PubMed search. All keywords in the PubMed were searched with the ‘(All fields)’ tag, which are processed using Automatic Term Mapping( 15 ). The Appendix documents the search algorithm in PubMed as an example. The search function ‘TS=Topic’ was used in Web of Science, which launches a search for topic terms in the fields of title, abstract, keywords and Keywords Plus®( 16 ). Titles and abstracts of the articles identified through the keyword search were screened against the study selection criteria. Potentially relevant articles were retrieved for evaluation of the full text. Two reviewers, J.W. and J.S., independently conducted title and abstract screening and identified potentially relevant articles. Inter-rater agreement was assessed using the Cohen’s kappa (κ=0·82). Discrepancies were resolved through face-to-face discussions between R.A., J.W. and J.S.

A reference list search (i.e. backward reference search) and a cited reference search (i.e. forward reference search) were conducted based on the full-text articles meeting the study selection criteria that were identified from the keyword search. Articles identified from the backward and forward reference search were further screened and evaluated using the same study selection criteria. The reference search was repeated on newly identified articles until no additional relevant article was found.

Study selection

Studies that met all of the following criteria were included in the review. (i) Setting: food pantry and/or food bank in the USA; (ii) exposure: any intervention that addresses food pantry clients’ diet-related outcomes (e.g. nutrition knowledge, food choice, food security, diet quality), except for the daily work routine of a food pantry (i.e. food service) or food bank (i.e. food storage and distribution); (iii) study design: randomized controlled trial (RCT) or pre–post study; (iv) study subjects: food pantry/bank clients; (v) article type: peer-reviewed publication; (vi) time window of search: from the inception of an electronic bibliographic database to 28 May 2018; and (vii) language: article written in English.

Studies that met any of the following criteria were excluded from the review: (i) food pantry/bank-related observational studies; (ii) non-peer-reviewed articles; (iii) articles not written in English; or (iv) letters, editorials, study/review protocols or review articles.

Data extraction

A standardized data extraction form was used to collect the following methodological and outcome variables from each included study: authors, publication year, study design, sample size, age range, percentage of women, duration of follow-up, setting, intervention type, intervention components, measures, outcomes, statistical models, covariates adjusted for and estimated intervention effectiveness.

Data synthesis

A tabulation of extracted data revealed that no two interventions provided a quantitative estimate for the same outcome measure. This precluded a meta-analysis. We narratively summarized the common themes and findings of the included studies.

Study quality assessment

We used the National Institutes of Health’s Quality Assessment Tool of Controlled Intervention Studies to assess the quality of each included study( 17 ). This assessment tool rates each study based on fourteen criteria. For each criterion, a score of 1 was assigned if ‘yes’ was the response, whereas a score of 0 was assigned otherwise (i.e. an answer of ‘no’, ‘not applicable’, ‘not reported’ or ‘cannot determine’). Study quality assessment helped measure the strength of scientific evidence but was not used to determine the inclusion of studies.

Results

Study selection

Figure 1 shows the study selection flowchart. We identified 3051 articles in total by the keyword search, including 610 articles from PubMed, 603 articles from Web of Science, 1412 from Scopus, 354 articles from CINAHL and seventy-two articles from Cochrane Library. After removing duplicates, 2446 unique articles entered title and abstract screening, of which 2436 articles were excluded. The full texts of the remaining ten articles were reviewed against the study selection criteria( Reference Wilson, Just and Swigert 18 – Reference Biel, Evans and Clarke 27 ) and two studies were excluded because they were other types of interventions (i.e. smoking cessation and medical referral) rather than diet-related interventions( Reference Perkett, Robson and Kripalu 19 , Reference Larsson and Kuster 23 ). A forward and backward reference search was conducted based on these eight articles and six new articles were identified that met the study selection criteria( Reference Greder, Garasky and Kleinet 28 – Reference Miyamoto, Chun and Kanehiro 33 ). Therefore, these fourteen articles consist of the final pool of studies included in the review( Reference Wilson, Just and Swigert 18 , Reference Caspi, Davey and Friebur 20 – Reference Martin, Wu and Wolff 22 , Reference Flynn, Reinert and Schiff 24 – Reference Miyamoto, Chun and Kanehiro 33 ).

Fig. 1 Flowchart showing study selection for the current review of food pantry-based interventions in the USA

Summary of the selected studies

Table 1 summarizes the basic characteristics of the fourteen articles evaluating twelve distinct interventions included in the review. All of them were published within the past 12 years. Seven studies adopted a pre–post study design and five adopted an RCT study design. Sample size varied substantially across studies. Two articles had a sample size between forty and 100 participants( Reference Caspi, Davey and Friebur 20 , Reference Flynn, Reinert and Schiff 24 ), seven had a sample size between 100 and 500 participants( Reference Wilson, Just and Swigert 18 , Reference Martin, Wu and Wolff 22 , Reference Martin, Shuckerow and O’Rourke 25 , Reference Martin, Colantonio and Picho 29 – Reference Eicher-Miller, Mason and Abbott 32 ), three articles had a sample size between 500 and 1000 participants( Reference Seligman, Lyles and Marshall 21 , Reference Clarke, Evans and Hovy 26 , Reference Greder, Garasky and Kleinet 28 ), one had a sample size between 1000 and 2000 participants( Reference Biel, Evans and Clarke 27 ), whereas the remaining one recruited 375 families( Reference Miyamoto, Chun and Kanehiro 33 ). The mean and median sample sizes were 429 and 236, respectively, except for one study that did not report its sample size in detail( Reference Miyamoto, Chun and Kanehiro 33 ). All studies but one( Reference Miyamoto, Chun and Kanehiro 33 ) focused exclusively on adults aged 18 years or above. Among the nine articles that reported sex distribution, women accounted for over half (53–100%) of the analytic sample( Reference Caspi, Davey and Friebur 20 – Reference Martin, Wu and Wolff 22 , Reference Flynn, Reinert and Schiff 24 , Reference Martin, Shuckerow and O’Rourke 25 , Reference Greder, Garasky and Kleinet 28 , Reference Martin, Colantonio and Picho 29 , Reference Yao, Ozier and Brasseur 31 , Reference Eicher-Miller, Mason and Abbott 32 ). Four articles recruited participants with diabetes( Reference Seligman, Lyles and Marshall 21 , Reference Martin, Wu and Wolff 22 , Reference Martin, Shuckerow and O’Rourke 25 , Reference Greder, Garasky and Kleinet 28 ), three articles recruited participants with hypertension( Reference Martin, Wu and Wolff 22 , Reference Martin, Shuckerow and O’Rourke 25 , Reference Greder, Garasky and Kleinet 28 ), two articles recruited participants with obesity( Reference Martin, Wu and Wolff 22 , Reference Martin, Shuckerow and O’Rourke 25 ) and one article recruited participants with heart disease( Reference Greder, Garasky and Kleinet 28 ).

Table 1 Basic characteristics of the studies included in the current review of food pantry-based interventions in the USA

RCT, randomized controlled trial; M, male; F, female.

Table 2 summarizes intervention type, intervention components, outcome measures, statistical models and estimated intervention effectiveness on diet-related outcomes. Nutrition education (n 9) was the most common type of intervention( Reference Caspi, Davey and Friebur 20 , Reference Flynn, Reinert and Schiff 24 – Reference Greder, Garasky and Kleinet 28 , Reference Yao, Ozier and Brasseur 31 – Reference Miyamoto, Chun and Kanehiro 33 ), followed by client-choice intervention (called ‘Freshplace’; n 3)( Reference Martin, Wu and Wolff 22 , Reference Martin, Shuckerow and O’Rourke 25 , Reference Martin, Colantonio and Picho 29 ), food display intervention (n 1)( Reference Wilson, Just and Swigert 18 ) and diabetes management intervention (n 1)( Reference Seligman, Lyles and Marshall 21 ). The nutrition education interventions included nutrition knowledge dissemination (e.g. healthy eating plate, nutrition facts label use, nutritional implications of different fat types, relationship between nutrition and health, and healthy recipes using fresh produce)( Reference Caspi, Davey and Friebur 20 , Reference Flynn, Reinert and Schiff 24 – Reference Greder, Garasky and Kleinet 28 , Reference Yao, Ozier and Brasseur 31 – Reference Miyamoto, Chun and Kanehiro 33 ) and cooking demonstrations( Reference Flynn, Reinert and Schiff 24 , Reference Biel, Evans and Clarke 27 ). In the nutrition education interventions, extension staff and local volunteers provided education pertaining to various nutrition-related facts and knowledge (e.g. read food labels, understand different types of fats) for low-income families( Reference Caspi, Davey and Friebur 20 ). Study investigators created a software to provide messages regarding tailored recipes and food-use tips for pantry clients( Reference Clarke, Evans and Hovy 26 , Reference Miyamoto, Chun and Kanehiro 33 ). Food pantry staff were trained about the relationship between nutrition and chronic diseases in order to provide healthier pantry food options( Reference Greder, Garasky and Kleinet 28 ). A food safety-certified graduate assistant served whole-grain dish along with the recipe, informed clients regarding the whole-grain ingredients in the recipe and asked them to make half their grains whole on a daily basis( Reference Yao, Ozier and Brasseur 31 ). In the cooking demonstration, study investigators provided cooking classes for low-income people who would like to try new recipes( Reference Martin, Wu and Wolff 22 ). The staff did a cooking demonstration to show how one could prepare healthy recipes using the fresh produce offered and distributed the recipes to pantry clients( Reference Biel, Evans and Clarke 27 ). The client-choice intervention (‘Freshplace’) included three major components: (i) participants chose their own foods (primarily fresh and perishable food items); (ii) met with a project manager once per month to develop and track personal goals for becoming food secure and self-sufficient; and (iii) received services tailored to their individual needs (e.g. a six-week cooking workshop)( Reference Martin, Wu and Wolff 22 , Reference Martin, Shuckerow and O’Rourke 25 , Reference Martin, Colantonio and Picho 29 ). In the food display intervention, researchers manipulated the display of a targeted product (i.e. protein bar) in a food pantry – placing the product in the front or the back of the category line and presenting the product in its original box or unboxed – with the goal of encouraging the selection of targeted foods through ‘nudges’ but without restricting choices( 1 ). In the diabetes management intervention, food pantry clients with diabetes were provided with diabetes-appropriate foods, blood sugar monitoring, primary care referral and self-management support by project personnel who were registered dietitians or certified diabetes educators( Reference Seligman, Lyles and Marshall 21 ).

Table 2 Intervention components, measures, statistical models and estimated effects on diet and health outcomes of the studies included in the current review of food pantry-based interventions in the USA

HbA1c, glycated Hb.

Two of the fourteen articles adopted one or more biometric outcome measures (e.g. BMI calculated from measured height and weight, glycaemic level and blood pressure)( Reference Seligman, Lyles and Marshall 21 , Reference Flynn, Reinert and Schiff 24 ), and the remaining twelve articles adopted subjective outcome measures using questionnaires (n 5)( Reference Martin, Wu and Wolff 22 , Reference Martin, Shuckerow and O’Rourke 25 , Reference Greder, Garasky and Kleinet 28 , Reference Martin, Colantonio and Picho 29 , Reference Eicher-Miller, Mason and Abbott 32 ), face-to-face or telephone-based interviews (n 5, including a 24 h dietary recall( Reference Caspi, Davey and Friebur 20 ))( Reference Caspi, Davey and Friebur 20 , Reference Clarke, Evans and Hovy 26 , Reference Clarke and Evans 30 , Reference Yao, Ozier and Brasseur 31 , Reference Miyamoto, Chun and Kanehiro 33 ), staff registration (n 1)( Reference Biel, Evans and Clarke 27 ) and researchers’ observation (n 1)( Reference Wilson, Just and Swigert 18 ). One of the fourteen articles adopted both biometric and subjective measures (e.g. interview and biometric measures)( Reference Flynn, Reinert and Schiff 24 ). Statistical tests and models applied included the t test, χ 2 test, Cronbach α test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, linear regression, logistic regression, ANOVA, hierarchical linear modelling and generalized linear mixed model.

All twelve studies included in the review found improvements in diet, cooking skills, food security, nutrition knowledge and/or health outcomes attributable to food pantry-based interventions. Among these studies, four reported positive qualitative outcomes linking the food pantry-based intervention to improved cooking skills( Reference Clarke and Evans 30 ), medical care( Reference Biel, Evans and Clarke 27 ), nutrition knowledge( Reference Greder, Garasky and Kleinet 28 ) and/or dietary quality among study participants( Reference Miyamoto, Chun and Kanehiro 33 ). The remaining eight studies that applied statistical tests and models reported a statistically significant positive association between the food pantry-based intervention and diet quality, cooking skills, food security, nutrition knowledge and/or health outcomes( Reference Wilson, Just and Swigert 18 , Reference Caspi, Davey and Friebur 20 – Reference Martin, Wu and Wolff 22 , Reference Flynn, Reinert and Schiff 24 – Reference Clarke, Evans and Hovy 26 , Reference Martin, Colantonio and Picho 29 , Reference Yao, Ozier and Brasseur 31 , Reference Eicher-Miller, Mason and Abbott 32 ). The nutrition education interventions and the client-choice intervention were found to improve participants’ nutrition knowledge, cooking skills, food security status and fresh produce intake( Reference Caspi, Davey and Friebur 20 , Reference Martin, Wu and Wolff 22 , Reference Flynn, Reinert and Schiff 24 – Reference Martin, Colantonio and Picho 29 , Reference Yao, Ozier and Brasseur 31 – Reference Miyamoto, Chun and Kanehiro 33 ). The food display intervention was found to significantly help pantry clients select healthier food items( Reference Wilson, Just and Swigert 18 ). The diabetes management intervention was found to significantly help participants better control their glycaemic level( Reference Seligman, Lyles and Marshall 21 ). More specifically, the glycaemic control intervention was more effective among the subset of participants with glycated Hb (HbA1c) ≥7·5% at baseline (i.e. improved by 0·48 percentage points) than those with diabetes in general (i.e. improved by 0·15 percentage points)( Reference Seligman, Lyles and Marshall 21 ). The only study that assessed BMI reported a reduction in BMI among food pantry clients following a six-week cooking programme of plant-based recipes, but the estimated intervention effect was only marginally significant (P=0·05)( Reference Flynn, Reinert and Schiff 24 ).

Study quality assessment

Table 3 reports criterion-specific ratings from the study quality assessment. All fourteen articles included in the review clearly stated the research question/objective, clearly specified and defined the study population, recruited subjects from the same or similar populations during the same time period, pre-specified and uniformly applied inclusion and exclusion criteria to all participants, had a reasonably long follow-up period that was sufficient for changes in outcomes to be observed, and implemented valid and reliable exposure and outcome measures. On the other hand, none of them examined the dose–response effect of food pantry-based interventions, and few justified their sample size and/or conducted a power calculation( Reference Wilson, Just and Swigert 18 , Reference Clarke, Evans and Hovy 26 ). Three articles had the outcome assessors blinded to the exposure status of the participants( Reference Wilson, Just and Swigert 18 , Reference Seligman, Lyles and Marshall 21 , Reference Flynn, Reinert and Schiff 24 ). Four articles had an attrition rate less than 20%( Reference Wilson, Just and Swigert 18 , Reference Martin, Wu and Wolff 22 , Reference Martin, Shuckerow and O’Rourke 25 , Reference Clarke, Evans and Hovy 26 ). Seven articles had a participation rate above 50%( Reference Martin, Wu and Wolff 22 , Reference Martin, Shuckerow and O’Rourke 25 , Reference Clarke, Evans and Hovy 26 , Reference Martin, Colantonio and Picho 29 – Reference Eicher-Miller, Mason and Abbott 32 ), assessed the exposures more than once during the study period( Reference Caspi, Davey and Friebur 20 – Reference Martin, Wu and Wolff 22 , Reference Flynn, Reinert and Schiff 24 – Reference Clarke, Evans and Hovy 26 , Reference Martin, Colantonio and Picho 29 ), and measured and statistically adjusted key potential confounding variables for their impact on the relationship between exposures and outcomes( Reference Wilson, Just and Swigert 18 , Reference Seligman, Lyles and Marshall 21 , Reference Martin, Wu and Wolff 22 , Reference Clarke, Evans and Hovy 26 , Reference Martin, Colantonio and Picho 29 , Reference Yao, Ozier and Brasseur 31 , Reference Eicher-Miller, Mason and Abbott 32 ).

Table 3 Quality assessmentFootnote * of the studies included in the current review of food pantry-based interventions in the USA

* The study quality assessment tool was adopted from the National Institutes of Health’s Quality Assessment Tool of Controlled Intervention Studies. For each criterion, a score of 1 was assigned if ‘yes’ was the response, whereas a score of 0 was assigned otherwise. Study quality assessment helped measure strength of scientific evidence but was not used to determine the inclusion of studies.

Discussion

The present study systematically reviewed scientific evidence regarding food pantry-based interventions on participants’ diet-related outcomes in the USA. A total of fourteen articles evaluating twelve distinct interventions were identified. Seven studies adopted a pre–post study design and the remaining five adopted an RCT design. Nine studies focused on nutrition education interventions, one study focused on client-choice intervention, one study focused on food display intervention and the remaining one focused on diabetes management intervention. The review findings demonstrated the feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of these food pantry-based interventions in producing a wide range of positive outcomes such as improved nutrition and health literacy, food security, cooking skills, healthy food choices and intake, diabetes management and access to community resources.

Since the current review was conducted, Seligman et al. (2018)( Reference Seligman, Smith and Rosenmoss 34 ) reported that food banks positively impacted food security, food stability and fruit/vegetable intake among participants. However, no differences in self-management (i.e. depressive symptoms, diabetes distress, self-care, hypoglycaemia and self-efficacy) or HbA1c were identified. On the one hand, findings from Seligman et al. (2018)( Reference Seligman, Smith and Rosenmoss 34 ) help strengthen the evidence regarding the effectiveness of food pantry-based interventions on food security and dietary quality. On the other hand, the null findings contradicted previous positive findings pertaining to improved HbA1c reported in Seligman et al. (2015)( Reference Seligman, Lyles and Marshall 21 ). Future studies should be conducted to assess this discrepancy.

Despite these initially promising results, food pantry-based interventions also face multiple challenges. Largely dependent upon donations and volunteer work, food pantries may have limited resources to provide additional services to clients in need( Reference Bazerghi, McKay and Dunn 6 , Reference Simmet, Depa and Tinnemann 11 , Reference Simmet, Depa and Tinnemann 12 , Reference Gany, Bari and Crist 35 ). Modifications of health behaviours and outcomes often require moderate to intensive interventions that last for a sustained period, but the shortage in personnel and funding may threaten the sustainability and suitability of food pantry-based interventions. Language and cultural barriers, lack of mutual trust and social stigma may prevent clients from fully engaging in the interventions offered at food pantries( Reference Chiu, Brooks and An 36 – Reference Fuller-Thomson and Redmond 40 ). This situation could be further hampered by food pantry staff’s lack of professional training in intervention delivery. A close collaboration between food pantry and health or other professionals might be the key to a successful and sustainable intervention. A potential partnership for these interventions may exist between food pantries and agencies implementing SNAP-Ed (i.e. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program–Education), who have staff that specialize in assisting organizations serving low-income populations( 41 ). SNAP-Ed implementing agencies provide free technical assistance and may help bridge the gap between pantry staff or funding shortages and the desire to implement sustained food pantry interventions.

Food insecurity is merely one of the many challenges food pantry clients face on a daily basis. Malnutrition among food pantry users has been strongly correlated with lack of shelter, access barriers to health care and other social resources, unemployment, physical and mental disability, illiteracy, substance abuse and domestic conflict( Reference Greenberg, Greenberg and Mazza 42 ). Findings of the current review revealed the potential of food pantry-based interventions in addressing some of the unmet needs of pantry users, especially in the domains of food insecurity and diet quality. The remaining questions are: what else could be done to support this highly vulnerable population, and how could we sustain interventions beyond the conclusion of research funding? Emerging research has explored non-diet related interventions at the food pantry setting, such as smoking cessation and medical referral programmes( Reference Perkett, Robson and Kripalu 19 , Reference Larsson and Kuster 23 ), in an effort to meet other needs of pantry users beyond food access. In view of the close link between food insecurity and health, Feeding America has started to promote partnerships between food pantries/banks and health-care providers( 43 ). As a pilot programme, a food pantry in Indiana was established in a health clinic to address the health and nutrition needs of senior patients and the neighbouring community( Reference Shockley 44 ). Sustainability of an intervention is largely determined by the abundance and stability of financial resources that cover the capital and labour cost of the intervention beyond the phase of scientific research. Demonstrating the intervention effectiveness and cost-effectiveness is of importance, but it alone may not be sufficient to attract and sustain long-term investment. Building a healthy partnership with other non-profit or for-profit institutes could help sustain the intervention in the long run if that is of their common interest. The Walmart Foundation has partnered with local food banks/pantries across the nation in a joint effort to improve the quantity and quality of food in the charitable meal system( 45 ). Resource and cost sharing based on partnerships can also play an important role in intervention sustainability. However, two recent studies assessed the network of agencies in local communities that promote healthy eating among populations with limited resources and found that those agencies were only loosely connected( Reference An, Loehmer and Khan 46 , Reference An, Khan and Loehmer 47 ).

The current review serves as the first attempt to synthesize scientific evidence regarding food pantry-based interventions on participants’ diet-related outcomes in the USA. Several limitations pertaining to the review and the included studies should be noted. The majority of the selected studies used subjective outcome measures (e.g. questionnaires and face-to-face or telephone-based interviews), which are subject to recall error and social desirability bias( Reference Bowling 48 , Reference Kaushal 49 ). Half of the articles adopted a pre–post study design. In the absence of randomization, their estimated intervention effects could be prone to confounding bias. Research quality varied substantially across studies. Merely two articles justified their sample size and/or conducted a power calculation. It is possible that some studies were underpowered to detect a statistically significant effect. Only four articles had an attrition rate less than 20%, which could be partially explained by the high turnover rate of food pantry clients and the difficulty in tracking them over time. All articles reported positive findings only, whereas it is possible that non-positive and/or inconclusive results were not reported or published (i.e. presence of publication and/or reporting bias). No two articles provided a quantitative effect estimate for the same type of food pantry-based intervention on the same diet-related outcome, which precluded a meta-analysis. None of the included studies assessed the dose–response effect of food pantry-based interventions. The presence of an optimal intervention intensity remains to be tested. Most studies were small in scale and it remains unclear whether some of those interventions are suitable for scaling up to accommodate the population needs. The current review only included published literature. There might be useful and relevant unpublished studies that were missed by the review. Future work could explore grey literature to see whether it could build on the findings from the current review. Biel et al. (2009) explored a collaboration model between community clinics and local food pantries to jointly address the unmet needs of low-income residents( Reference Biel, Evans and Clarke 27 ). However, such partnership is uncommon. Future work should incorporate larger sample sizes and diverse participants, examine the dose–response effect of the intervention, build collaboration with other public or private entities, and design innovative interventions to address other types of unmet needs of food pantry users.

Conclusions

The present work systematically reviewed scientific evidence regarding food pantry-based interventions on clients’ diet-related outcomes. Fourteen articles evaluating twelve distinct interventions were identified from the keyword and reference search, including nine nutrition education interventions, a client-choice intervention, a food display intervention and a diabetes management intervention. All fourteen articles included in the review clearly stated the research question/objective, clearly specified and defined the study population, recruited subjects from the same or similar populations during the same time period, pre-specified and uniformly applied inclusion and exclusion criteria to all participants, had a reasonably long follow-up period that was sufficient for changes in outcomes to be observed, and implemented valid and reliable exposure and outcome measures. On the other hand, none of them examined the dose–response effect of food pantry-based interventions, only two justified their sample size and/or conducted a power calculation, three had the outcome assessors blinded to the exposure status of the participants and four had an attrition rate less than 20%. Findings from these studies demonstrated the feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of food pantry-based interventions in delivering a wide range of positive outcomes including improved nutrition and health literacy, food security, cooking skills, healthy food choices and intake, diabetes management and access to community resources. Future studies are warranted to address the challenges of conducting interventions in food pantries, such as shortage in personnel and resources, to ensure intervention sustainability and long-term effectiveness.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This research is partially funded by Guangzhou Sport University. Guangzhou Sport University had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare. Authorship: R.A. conceived and designed the study and wrote the manuscript. J.W. and J.L. conducted the literature review and constructed the summary tables and figures. E.L. and J.M. contributed to manuscript drafting. J.S. contributed to manuscript revision. Ethics of human subject participation: This review is non-human subject research and exempt from institutional review board review.

Appendix

Search algorithm in PubMed

‘food pantry’(All Fields) OR ‘food pantries’(All Fields) OR ‘food bank’(All Fields) OR ‘food assistance’(MeSH) AND (‘humans’(MeSH Terms) AND English(lang))