Diets high in fruits and vegetables decrease the risk of developing CVD, stroke, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, overweight, obesity and several types of cancer( 1 ). Among all nutritional factors, the strongest inverse correlations with death rates in several European countries are found for the consumption of fruit and vegetables( Reference Stefler, Pikhart and Kubinova 2 – Reference Bamia, Trichopoulos and Ferrari 4 ). In 2012, a comparative risk assessment of the global burden of disease identified diets low in fruits and vegetables to be among the five leading risk factors worldwide( Reference Lim, Vos and Flaxman 5 ). In the Netherlands, only 8 % of adults consume the recommended daily amount of vegetables of 200 g or more and 13 % consume two or more pieces of fruit daily( Reference van Rossum, Fransen and Verkaik-Kloosterman 6 ). Moreover, the consumption of fruits and vegetables is unequally distributed across the population. Individuals with lower socio-economic position (SEP) eat less fruits and vegetables and meet the dietary guidelines less often compared with individuals with higher SEP( Reference Malon, Deschamps and Salanave 7 – Reference Dijkstra, Neter and Brouwer 10 ). It is suggested that perceived affordability of healthy food products plays an important role in SEP differences in dietary intake( Reference Williams, Thornton and Crawford 11 – Reference Giskes, Turrell and Patterson 14 ), although the evidence is not conclusive( Reference Kamphuis, de Bekker-Grob and van Lenthe 15 , Reference Giskes, Van Lenthe and Brug 16 ).

In 2008, the world economy entered a severe economic crisis. This crisis increased income inequalities in many countries and the consequences of the economic crisis may be more severe for those with a lower SEP( 17 ). Reports from the Institute for Fiscal Studies and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development showed that households decreased their food expenditures since the beginning of the crisis and switched to lower priced and less healthy foods( Reference Griffith, O’Connell and Smith 18 , 19 ). A study from Iceland showed that the crisis was associated with a significant reduction in the consumption of fruits and vegetables( Reference Asgeirsdottir, Corman and Noonan 20 ). An Australian study showed that individuals who experienced financial distress during the crisis had a 20 % higher risk to become obese than those who did not suffer from such distress( Reference Siahpush, Huang and Sikora 21 ). Furthermore, the price gap between healthy and unhealthy foods has grown between 2002 and 2012( Reference Jones, Conklin and Suhrcke 22 ). Healthy foods like fruits and vegetables became relatively more expensive, while unhealthy foods became relatively cheaper. Thus, the occurrence of the economic crisis and the higher price of healthier foods may have had the largest budget impact on those with a lower SEP and may have been a barrier to eating a healthy diet. However, the change in socio-economic inequalities in the intake of fruits and vegetables over this particular period of time is unknown, while a negative change for the lowest socio-economic groups may potentially have an impact on the widening of socio-economic inequalities in diet and consequently in health inequalities. Understanding these changes is crucial for the development of interventions and policies to improve dietary intake and reduce diet-related chronic diseases in lower socio-economic groups. If trends vary by specific socio-economic subgroups, interventions and policies need to be tailored to the needs and capacities of the target population.

The longitudinal Dutch GLOBE study is designed to investigate the causes of socio-economic differences in the health and health behaviours of adults( Reference Jones, Conklin and Suhrcke 23 ). Information about dietary intake collected in 2004 and 2011 provides the opportunity to investigate how the intake of fruits and vegetables changed during a time of economic crisis for higher and lower socio-economic groups. Therefore, the aim of our study was to investigate whether the intake of fruits, cooked vegetables, raw vegetables and fruit juice changed between 2004 and 2011 and to determine SEP differences in intake and intake change. Furthermore, we explored if financial barriers could explain potential SEP differences in the change of fruit and vegetable intake between 2004 and 2011.

Methods

GLOBE study

The study sample consisted of participants of the longitudinal GLOBE study, conducted in the south-east of the Netherlands. The aim of the GLOBE study is to investigate mechanisms and underlying factors contributing to socio-economic differences in health. Detailed information on the sampling and design of the GLOBE study, as well as results obtained in the first 10 years of the study, are provided elsewhere( Reference van Lenthe, Kamphuis and Beenackers 23 – Reference van Lenthe, Schrijvers and Droomers 25 ). Briefly, the sample for GLOBE was randomly drawn from the municipal population registries, stratified by age, SEP and degree of urbanization. In 1991 a postal questionnaire was sent to 27070 inhabitants of eighteen municipalities aged 15–78 years (response rate=70·1 %, N 18973). Sub-samples (total n 5667) were interviewed and/or surveyed in 1991, 1997 and 2004 (also including a new sample). In 2011, a large-scale postal survey was administered in a new wave of data collection. Of the respondents of the previous survey of 2004 (n 4784), 249 had died, seventy-six had emigrated and fourteen were lost to follow-up (i.e. no correct address information available). This resulted in a sample of n 4445 that was sent the 2011 survey. A total of 2983 respondents returned the survey (response rate=67·2 %). We excluded five respondents because all required dietary intake data were missing, leaving 2978 respondents for the descriptive statistics and 2970 for the regression analyses.

Fruit, cooked vegetable, raw vegetable and fruit juice consumption

Respondents were asked to complete a validated FFQ in 2004 and 2011, which included questions about the intake frequency of fruits, cooked vegetables, raw vegetables and fruit juice, separately( Reference Van Assema, Brug and Ronda 26 , Reference Bogers, Van Assema and Kester 27 ). The FFQ did not ask for different types of fruits or vegetables. In concordance with the Dutch dietary guidelines, a potato was not considered a vegetable( 28 ). In this FFQ respondents were asked to estimate how many days per week they usually consumed fruits, boiled/baked/steamed vegetables, raw vegetables and fruit juices in the past month. Additionally, in 2004, respondents were asked in an open question to indicate the number of days per week these products were consumed. In 2011, respondents were asked the same question but could choose between the following answer categories: never, <1, 1–2, 3–4, 5–6 and 7 d/week. To compare the consumption between 2004 and 2011, we categorized the number of days per week indicated in 2004 into the corresponding 2011 categories and labelled this variable ‘intake frequency’. In both waves, respondents were also asked to indicate the average portion size of each food product; however, because of the high number of missing values, this information could not be used in the analyses. The questionnaires were filled out in the autumn (October/November) in both waves.

Socio-economic position

SEP was defined by self-reported level of education and household income( Reference Galobardes, Morabia and Bernstein 29 ). In 2004 respondents were asked to indicate their highest level of completed education. The eight categories, from which respondents could choose, were combined into four categories: elementary (less than or primary education), lower secondary (lower professional and intermediate general education), higher secondary (intermediate professional and higher general education) and tertiary (higher professional education and university)( Reference van Berkel-van Schaik and Tax 30 ). Respondents were also asked to indicate their net monthly household income (0–1200€, >1200–1800€, >1800–2600€ and >2600€) in 2004. Household income was defined as the respondent’s income plus income of a partner (if applicable), and included the income of children only if it was shared with the household.

Potential mediators

In 2004, respondents were asked to indicate if they agreed with the proposition that vegetables are expensive (yes/no). If yes, they were asked to indicate if this was a barrier for them to consume vegetables (often, sometimes and sporadic/never). These questions were combined in the financial barrier ‘vegetables are expensive’ and categorized as ‘yes’ (‘vegetables are expensive’ and ‘I often/sometimes perceive this to be a barrier for consumption’) or ‘no’ (‘vegetables are not expensive’ or ‘vegetables are expensive and I sporadically/never perceive this to be a barrier for consumption’). Exactly the same questions were asked with regard to fruits (not fruit juice) and combined in the barrier ‘fruits are expensive’. In 2011, the occurrence of financial distress was assessed. Respondents were asked to indicate if they had experienced difficulties in paying for food, rent, electricity bill, etc. during the past year. The financial barrier ‘financial distress’ was categorized as ‘no’ or ‘sometimes/yes’.

Potential confounders

Demographics included age (<40, 40–60 and >60 years old), sex, marital status (married, single, divorced, widowed), employment status (employed, unemployed, non-active), country of birth (Netherlands v. other) and living arrangement (living together with partner, living alone, other).

Lifestyle factors included BMI (self-reported weight (in kilograms) divided by the square of self-reported height (in metres)), smoking (never, former, current), physical activity (days per week physically active for ≥30 min/d) and perceived general health (excellent, very good, good, moderate, poor).

Statistical analyses

We used descriptive statistics to summarize the characteristics of the study sample and the intake frequency of fruits, cooked vegetables, raw vegetables and fruit juice in 2004 and 2011. Spearman’s correlation coefficient was calculated to investigate the intercorrelation between the SEP indicators (education and income).

For the regression analyses all missing data (independent and dependent variables, confounders, effect modifiers and mediators), excluding eight respondents because level of education was ‘other’, were imputed with multiple imputation via the predictive mean matching method( Reference Little 31 ). Imputations were based on the associations between all the variables included in the study. Forty imputed data sets were generated and pooled estimates from these forty imputed data sets were used to report OR and their 95 % CI. We used the number of imputed data sets that is equal to the percentage of people with one or more missing variables in the data set. Ordinal logistic regression analyses were used to investigate the association between SEP and intake frequency of fruits, cooked vegetables, raw vegetables and fruit juice, because the dependent variable (intake frequency) consisted of ordered discrete categories( Reference Ananth and Kleinbaum 32 ). The proportional odds assumption was tested with the test of parallel lines. No assumptions were violated. Potential confounders were evaluated by adding the variables separately to the models adjusted for age and sex and examining the change in point estimates of the independent variable. If the estimate changed more than 10 %, the variable was considered a confounder. However, this was not the case for any of the variables and therefore the final analyses were adjusted only for age and sex. Tests for trend were performed by including the SEP indicators as ordinal variables in the models. Effect modification by age and sex was examined by adding interaction terms to the multivariate models.

To investigate the association of SEP with intake frequencies in 2004 and 2011 we used two models. Model 1 included level of education or income in 2004 and was adjusted for the variables age and sex; and model 2 was additionally adjusted for the other SEP indicator in 2004. When mutually adjusting for both SEP indicators, we interpreted the remaining statistically significant OR to indicate the magnitude of the independent effect of the SEP indicator in question. The OR represent the likelihood to report a lower intake frequency of fruits, cooked/raw vegetables or fruit juice than the reference group (highest SEP). To investigate the association between SEP in 2004 with change in intake frequency of fruits, cooked vegetables, raw vegetables and fruit juice between 2004 and 2011, we adjusted the intake in 2011 for the intake in 2004. These OR represent the likelihood to report a decrease in intake frequency between 2004 and 2011 compared with the reference group (highest SEP). Again, two models were used: model 1 included level of education or income in 2004 with adjustment for age, sex and the intake frequency in 2004; and model 2, similar to model 1, but with additional adjustment for the other SEP indicator in 2004.

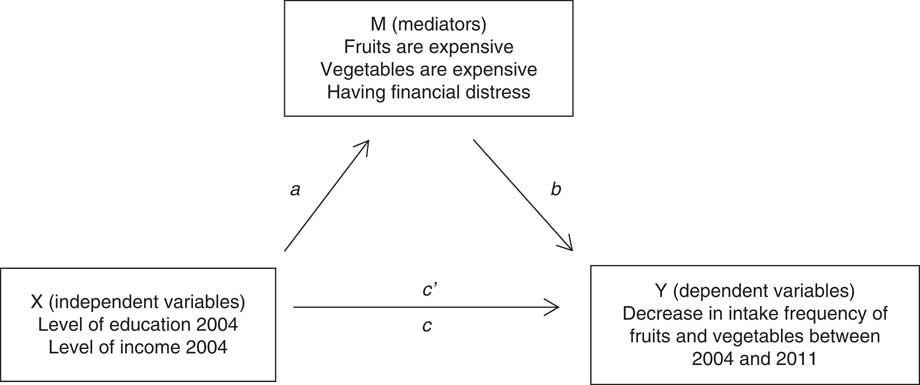

To investigate the contribution of financial barriers relating to the price of fruits and vegetables and having financial distress to SEP differences in the change of intake frequency between 2004 and 2011, we followed the mediation approach of Baron and Kenny( Reference Baron and Kenny 33 ) (see Fig. 1 for conceptual mediation model). Step 1 in this approach is to link the dependent (decrease in intake frequency between 2004 and 2011) to the independent variables (level of income or education in 2004). Step 2 is to show a statistically significant association between the independent variable (level of income or education in 2004) and the mediators (financial barriers). Step 3 is to show a statistically significant association between the mediator (financial barriers) and the dependent variable (decrease in intake frequency between 2004 and 2011), when controlling for the independent variable (level of income or education in 2004). If all steps are confirmed, the attenuation of the effect size in step 3 can be interpreted as the influence of the mediator. We performed the last step only for the mediators that fulfilled all three steps. To assess the magnitude of the attenuation, we calculated the percentage change in OR using the following formula: %attenuation=[(OR model−OR base model)/OR base model]×100. Interaction between the final mediators, income and education was tested, but no interaction was found.

Fig. 1 Conceptual mediation model according to Baron and Kenny( Reference Baron and Kenny 33 ) for the association between level of income and education in 2004 and the decrease in intake frequency of fruits and vegetables between 2004 and 2011. Path a represents the association between X and M and path b represents the association between M and Y, adjusted for X. Path c′ is the direct effect and path c is the total effect between X and Y

Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 20.0 and P<0·05 was considered statistically significant (two-tailed).

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of 2978 participants who were included in our sample both in 2004 and 2011. There were slightly more females (54·2 %) than males and the mean age for the total sample was 53·4 (sd 13·4) years (range=25–75 years). Most respondents reported to have finished lower secondary (33·6 %) or tertiary education (30·4 %) and were categorized in the highest income category (>2600€/month; 28·6 %), followed by the second highest income category (>1800–2600€/month; 25·8 %). A quarter of the respondents reported to have experienced financial distress during the past year in 2011 (25·0 %). In 2004, 12·9 % perceived the high price of vegetables a barrier for purchase and 14·5 % perceived the high price of fruits a barrier for purchase. The Spearman intercorrelation coefficient (r) of income and education was 0·52.

Table 1 Characteristics of the sample of Dutch adults from the GLOBE study in 2004 (n 2978)

SEP, socio-economic position.

Intake frequencies in 2004 and in 2011

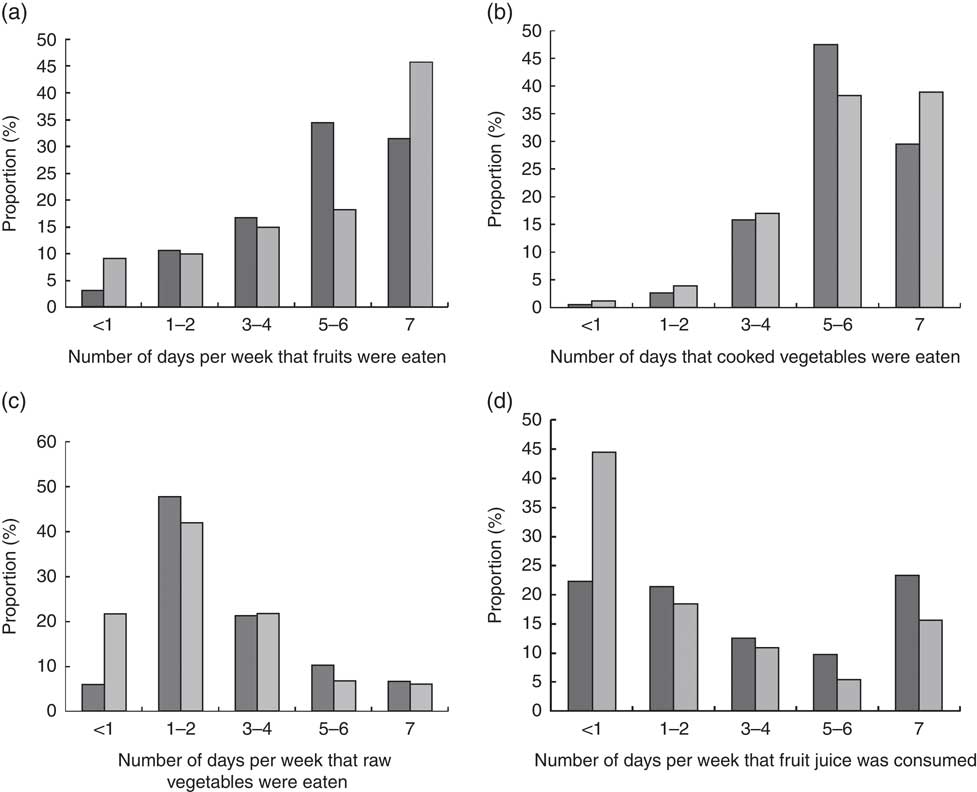

Figure 2 shows the intake frequency (number of days per week consumed) of fruits, cooked vegetables, raw vegetables and fruit juice in 2004 as well as 2011. Table 2 shows the number of respondents who decreased, increased or stabilized their intake frequency of fruits, cooked vegetables, vegetables and fruit juice between 2004 and 2011 in total and by level of education and level of income in 2004. Between 2004 and 2011, 46·7 % of the respondents decreased their intake frequency of fruits, 18·5 % remained stable and 29·9 % increased. Of those who decreased, 51·4 % decreased fruit intake by one day per week, 24·7 % by two and 12·6 % by three days per week. Of those who increased, 65·5 % increased their fruit intake by one day per week, 19·1 % by two and 9·8 % by three days per week (data not shown). For cooked vegetables, 52·5 % of the respondents decreased their intake frequency between 2004 and 2011, 24·0 % remained stable and 18·8 % increased. Of those who decreased, 66·1 % decreased cooked vegetable intake by one day per week, 20·7 % by two and 8·2 % by three days per week. Of those who increased, 72·3 % increased their cooked vegetable intake by one day per week, 21·2 % by two and 4·9 % by three days per week (data not shown). For raw vegetables, 19·2 % of the respondents decreased their intake frequency between 2004 and 2011, 15·0 % remained stable and 55·4 % increased. Of those who decreased their intake, 48·0 % decreased their raw vegetable intake by one day per week, 38·5 % by two and 9·9 % by three days per week. Of those who increased, 49·6 % increased their raw vegetable intake by one day per week, 25·7 % by two and 13·9 % by three days per week (data not shown). For fruit juice, 36·3 % decreased increased their intake frequency between 2004 and 2011, 9·0 % remained stable and 39·3 % increased. Of those who decreased, 51·5 % decreased their fruit juice intake by one day per week, 24·6 % by two and 13·3 % by three days per week. Of those who increased, 40·1 % increased their fruit juice intake by one day per week, 15·3 % by two and 14·6 % by three days per week (data not shown).

Fig. 2 The number of days per week that (a) fruits, (b) cooked vegetables, (c) raw vegetables and (d) fruit juice were consumed in 2004 (![]() ) and 2011 (

) and 2011 (![]() ) by Dutch adults (n 2978) aged 25–75 years, the GLOBE study. Charts do not add up to 100 % due to missing data

) by Dutch adults (n 2978) aged 25–75 years, the GLOBE study. Charts do not add up to 100 % due to missing data

Table 2 Number of respondents who decreased, increased or remained stable regarding the number of days per week they consumed fruits, cooked vegetables, raw vegetables and fruit juice in 2011 compared with 2004, by level of education and level of income in 2004: Dutch adults (n 2978) aged 25–75 years, the GLOBE study

* Lines do not add up to total n and % due to missing data.

Socio-economic differences in intake frequencies in 2004

Respondents in the lowest income group in 2004 had a 1·34 higher odds (95 % CI 1·02, 1·77) to report a lower intake frequency in 2004 of cooked vegetables compared with those in the highest income group (Table 3). Respondents in the lowest or lower education group in 2004 had a higher odds to report a lower intake frequency in 2004 of fruits (OR=1·48; 95 % CI 1·10, 2·00), cooked vegetables (OR=1·29; 95 % CI 1·06, 1·58), raw vegetables (OR=1·56; 95 % CI 1·14, 2·14) and fruit juice (OR=1·44; 95 % CI 1·19, 1·74) compared with those in the highest education group.

Table 3 OR and 95 % CI for the association of level of income and level of education in 2004 with a lower intake frequencyFootnote * in 2004 of fruits, cooked vegetables, raw vegetables and fruit juice compared with the highest group: Dutch adults (n 2970) aged 25–75 years, the GLOBE study

Ref., reference category; SEP, socio-economic position.

Significant results are indicated in bold font.

* The intake frequency is the number of days per week that fruits, cooked vegetables, raw vegetables and fruit juice were consumed in 2004 (<1, 1–2, 3–4, 5–6, 7 d/week).

† Model 1: model adjusted for sex and age.

‡ Model 2: additionally adjusted for the other SEP indicator in 2004 (level of income or education).

§ The estimates represent the likelihood to report lower intake frequency of fruits, cooked vegetables, raw vegetables and fruit juice compared with the reference group.

Socio-economic differences in changes in intake frequencies in 2011

Respondents in the lowest income group in 2004 had a higher odds to report a lower intake frequency in 2011 of cooked vegetables (OR=1·71; 95 % CI 1·33, 2·20) and raw vegetables (OR: 1·67, 95 % CI 1·29, 2·17) compared with those in the highest income group (Table 4). Respondents in the lowest education group in 2004 had a higher odds to report a lower intake frequency in 2011 of fruit (OR=1·59; 95 % CI 1·17, 2·16), cooked vegetables (OR=1·51; 95 % CI 1·12, 2·05), raw vegetables (OR=1·97; 95 % CI 1·45, 2·68) and fruit juice (OR=1·41; 95 % CI 1·03, 1·94) compared with those in the highest education group.

Table 4 OR and 95 % CI for the association of level of income and level of education in 2004 with a lower intake frequencyFootnote * in 2011 of fruits, cooked vegetables, raw vegetables and fruit juice compared with the highest group: Dutch adults (n 2970) aged 25–75 years, the GLOBE study

Ref., reference category; SEP, socio-economic position.

Significant results are indicated in bold font.

* The intake frequency is the number of days per week that fruits, cooked vegetables, raw vegetables and fruit juice were consumed in 2011 (<1, 1–2, 3–4, 5–6, 7 d/week).

† Model 1: model adjusted for sex and age.

‡ Model 2: additionally adjusted for the other SEP indicator in 2004 (level of income or education).

§ The estimates represent the likelihood to report lower intake frequency of fruit, cooked vegetables, raw vegetables and fruit juice compared with the reference group.

Socio-economic differences in a decrease in intake frequencies between 2004 and 2011

Between 2004 and 2011, the respondents in the lowest income group in 2004 had a higher odds to report a decrease in intake frequency of cooked vegetables (OR=1·62; 95 % CI 1·23, 2·11) and raw vegetables (OR=1·64; 95 % CI 1·25, 2·15) compared with those in the highest or higher income group (Table 5). The respondents in the lowest or lower education group in 2004 had a higher odds to report a decrease in intake frequency between 2004 and 2011 of fruits (OR=1·49; 95 % CI 1·08, 2·06), cooked vegetables (OR=1·45; 95 % CI 1·06, 2·00), raw vegetables (OR=1·75; 95 % CI 1·27, 2·39) and fruit juices (OR=1·28; 95 % CI 1·03, 1·57) compared with those in the highest education group.

Table 5 OR and 95 % CI for the association of level of income and level of education in 2004 with a decrease in intake frequencyFootnote * between 2004 and 2011 of fruits, cooked vegetables, raw vegetables and fruit juice compared with the highest group: Dutch adults (n 2970) aged 25–75 years, the GLOBE study

Ref., reference category; SEP, socio-economic position.

Significant results are indicated in bold font.

* The intake frequency is the number of days per week that fruits, cooked vegetables, raw vegetables and fruit juice were consumed in 2011 (<1, 1–2, 3–4, 5–6, 7 d/week).

† Model 1: adjusted for sex, age and the intake frequency of fruit, cooked vegetables, raw vegetables or fruit juice in 2004.

‡ Model 2: additionally adjusted for the other SEP indicator in 2004 (level of income or education).

§ The estimates represent the likelihood to report a decrease in intake frequency of fruits, vegetables, raw vegetables and fruit juice between 2004 and 2011 compared with the reference group.

The mediating role of financial barriers in socio-economic differences in the decrease in intake frequencies between 2004 and 2011

The results of step 1 of the mediation analyses are already presented in Table 5. The results of step 2 show that the respondents in the lowest income group in 2004 had a higher odds to report the financial barrier ‘fruits are expensive’ (OR=4·07; 95 % CI 2·81, 5·89) and ‘vegetables are expensive’ (OR=3·46; 95 % CI 2·33, 5·13) or ‘financial distress’ (OR=10·53; 95 % CI 7·39, 15·03) compared with those in the highest income group (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1).

The respondents in the lowest education group in 2004 had a higher odds to report the barrier ‘fruits are expensive’ (OR=1·71; 95 % CI 1·10, 2·64) and ‘vegetables are expensive’ (OR=3·53; 95 % CI 2·22, 5·62) or ‘financial distress’ (OR=2·74; 95 % CI 1·88, 3·98) compared with respondents in the highest education group. These associations were adjusted for level of income in 2004, gender and age (Supplemental Table 1).

The results of step 3 show that respondents reporting the barrier ‘fruits are expensive’ had a 1·42 higher odds (95 % CI 1·16, 1·75) to report a decrease in cooked vegetable intake frequency between 2004 and 2011 than respondents who did not report this barrier (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 2). Respondents who reported the barrier ‘vegetables are expensive’ had a 1·31 higher odds (95 % CI 1·05, 1·63) to report a decrease in intake frequency of cooked vegetables between 2004 and 2011 compared with respondents who did not report this barrier. Respondents reporting the barrier ‘financial distress’ had a 1·26 higher odds (95 % CI 1·06, 1·50) to report a decrease in intake frequency of fruits between 2004 and 2011 compared with respondents who did not report this barrier.

For the last step, we continued only with those variables that fulfilled all conditions of the Barron and Kenny approach (Table 6). The association between level of income in 2004 and the decrease in intake frequency of cooked vegetables between 2004 and 2011 was adjusted for the barrier ‘fruits are expensive’ and ‘vegetables are expensive’. The barrier ‘fruits are expensive’ explained 0·9 to 7·4 % and the barrier ‘vegetables are expensive’ explained 1·5 to 5·2 % of the difference in decrease in intake frequency of cooked vegetables between people having different levels of income. The association between level of education in 2004 and the decrease in intake frequency of fruits between 2004 and 2011 was adjusted for the barrier ‘financial distress’; and the association between level of education in 2004 and the decrease in intake frequency of cooked vegetables between 2004 and 2011 for the barriers ‘fruits are expensive’ and ‘vegetables are expensive’. The barrier ‘financial distress’ explained 1·6 to 3·5 % of the difference in decrease in intake frequency of fruits between people having different levels of education. The barrier ‘fruits are expensive’ explained 0·7 to 2·8 % and ‘vegetables are expensive’ explained 2·1 to 4·3 % of the difference in decrease in intake frequency of cooked vegetables between people having different levels of education.

Table 6 OR and 95 % CI for the association of level of income and level of education in 2004 with a decrease in intake frequencyFootnote * between 2004 and 2011 of fruits and cooked vegetables additionally adjusted for financial barriers and the magnitude of the attenuation: Dutch adults (n 2970) aged 25–75 years, the GLOBE study

X, did not fulfil the conditions of all three steps of Baron and Kenny( Reference Ananth and Kleinbaum 32 ); Ref., reference category; SEP, socio-economic position.

Significant results are indicated in bold font.

* The intake frequency is the number of days per week that fruits and cooked vegetables were consumed in 2011 (<1, 1–2, 3–4, 5–6, 7 d/week).

† Base model: adjusted for sex, age, the intake frequency of fruits or cooked vegetables in 2004 and the other SEP indicator in 2004.

‡ The estimates represent the likelihood to report a decrease in intake frequency between 2004 and 2011 of fruits and cooked vegetables compared with the reference group.

§ % attenuation=[(OR model with mediator−OR base model)/OR base model]×100.

Discussion

The present study among Dutch adults showed a widening of relative income and education differences in fruit, cooked and raw vegetables and fruit juice intake between 2004 and 2011. The financial barriers ‘fruits are expensive’, ‘vegetables are expensive’ and ‘financial distress’ each explained a small part of the observed decreases in fruit and cooked vegetable intake among lower income and education groups between 2004 and 2011.

The present study extends previous research by examining the relative SEP differences in changes in dietary intakes within a sample of Dutch adults, using both education and income as indicators of SEP, to study financial barriers as potential explanation for the observed differences in changes between SEP groups. The results of our study suggest that the influence of income and education in the sample on fruit and vegetable intake became stronger between 2004 and 2011. Even though the Netherlands is a wealthy and economically developed country, the present study’s findings show that also in developed countries the income and education differences in fruit and vegetable intake are increasing and consequently widening socio-economic health differences.

Studies on how socio-economic disparities in eating behaviours develop over time and especially during an economic crisis are limited. Nevertheless, our results support findings of some previous studies which suggested that, during the economic crisis, socio-economic differences in dietary intake widened. A previous observational study from Greece on dietary behaviour revealed that SEP disparities in healthy eating increased during 2006 and 2011( Reference Filippidis, Schoretsaniti and Dimitrakaki 34 ). In that study the consumption of at least five portions of fruits and vegetables daily decreased significantly among lower SEP groups (from 9·0 to 4·1 %). An Italian study showed that adherence to the healthy Mediterranean diet decreased considerably between 2007 and 2011 and that socio-economic indicators became major determinants of adherence to the Mediterranean diet, which was suggested to be caused by the economic crisis( Reference Bonaccio, Di Castelnuovo and Bonanni 35 ). A study in Iceland showed that the economic crisis was associated with reductions in various health behaviours between 2007 and 2009, including the consumption of fruits and vegetables( Reference Asgeirsdottir, Corman and Noonan 20 ). However, it is important to mention that none of these studies directly investigated the impact of the crisis on dietary intake and that the effects of a crisis can be complex. Future research must find out if the emergence of the economic crisis and its consequences underlie changes in dietary intake or whether other developments or factors were involved.

Having financial distress and concerns regarding the high price of fruits and vegetables explained a small part of the observed income and education differences in the decrease in intakes between 2004 and 2011. Previous cross-sectional studies support these findings and reported mediating effects of price concerns on fruit and vegetable intake among different SEP groups( Reference Aggarwal, Monsivais and Cook 36 – Reference Beydoun and Wang 38 ). There are indications in the literature that healthy diets cost more than unhealthy diets( Reference Darmon and Drewnowski 39 ), although contrasting evidence exists as well( Reference Winkler, Turrell and Patterson 40 ). Australian data show that the average cost of a healthy 7 d meal plan requires 20 % of the income of an average-income family, but double that for a welfare-dependent family( Reference Kettings, Sinclair and Voevodin 41 ). In our study, one out of four respondents reported to have experienced financial problems during the last year (25 %) and 13 and 15 % of the respondents reported that vegetables and fruits, respectively, are expensive to buy. These findings emphasize again the role of income in socio-economic differences in fruit and vegetable intake, which may be partly dependent on the pricing of fruits and vegetables. An important question is whether removal of the price barriers would lead to a higher intake of fruits and vegetables, particularly among those in lower socio-economic groups. Food pricing strategies including taxation and subsidies may be effective in influencing dietary intake( Reference Mozaffarian, Rogoff and Ludwig 42 ). Indeed, recent studies showed that a price discount on fruits and vegetables increased the purchase of fruits and vegetables, especially in low SEP groups( Reference Waterlander, de Boer and Schuit 43 , Reference Ball, McNaughton and Le 44 ). Future research must continue to investigate the role of financial barriers in SEP differences in dietary intake over time and if the implementation of taxes and subsidies to improve diet quality can be effective in a real-life setting and could decrease SEP differences in intake.

The financial barriers investigated in our study explained only a small proportion of the differences in changes of intake frequency of fruits and cooked vegetables between 2004 and 2011. This suggests that many other factors underlie the socio-economic differences in dietary intake. According to the commonly used socio-ecological model there are four key domains that are associated with the quality of dietary intake, including the individual, interpersonal, community and societal domain( Reference Bronfenbrenner 45 ). Individual factors associated with diet quality include knowledge about healthy eating, intention or motivation to eat a healthy diet, age, gender and health status. Interpersonal factors include food availability at home, cultural factors regarding healthy eating and social support from others to eat a healthy diet. Examples of community factors associated with diet quality are food availability in shops, at the workplace and when eating out. Societal factors include the dietary guidelines of a country, public health policies, retail, marketing and media. The impact of all these various factors operating at each domain may vary according to socio-economic group. Before developing new interventions, future research should focus on providing insights into the most relevant causes and mechanisms that underlie socio-economic differences in dietary intake. It is only then that interventions can be adequately designed and tailored to the needs and capacities of the target population( Reference Ball 46 ). Without taking adequate account of the most important underlying causes, interventions run the risk of failing to benefit the lower SEP groups, or even to widen the differences in dietary intake and consequently health.

Our study has a number of strengths and limitations. The main strength of our study is that we investigated changes in SEP differences in dietary intake during a period of economic crisis. Therefore, the study adds valuable information to the recent literature. Furthermore, the GLOBE sample was representative of the source population of residents aged 25–74 years who resided in Eindhoven and surroundings in 2004 and were born in the Netherlands. We were able to include two different SEP indicators and different financial barriers which allowed us to study potential mediators to provide insights into the complex character of socio-economic differences in dietary intake. Furthermore, a strength of the analytical approach is the use of multiple imputations to handle missing data. Limitations of our study should be noted as well. All data, including the dietary and socio-economic information, were self-reported, which may have resulted in biased responses. Furthermore, we were able to report only the number of days that fruits and vegetables were eaten per week, because of high numbers of missing data on portion sizes. This may have resulted in biased results in change in intake of fruits and vegetables between 2004 and 2011. The financial barriers in the study did not account for a lot of variability in the dietary intake changes and it should be taken into account that food frequencies are measured with the corresponding error; therefore, the associations are likely to be subject to measurement error with potential attenuation of the results. Furthermore, between 2004 and 2011 a substantial number or participants died, immigrated or could not be traced. Therefore, potential biases due to loss to follow-up cannot be excluded. Moreover, we specifically focused on fruits and vegetables and used these as indicators of a healthy diet. To provide a better understanding on SEP differences in dietary intake over time, future research should also investigate other food products, including unhealthier products such as savoury snacks, sweet snacks and sugar-sweetened beverages. In addition, the mediation approach that we chose has disadvantages and better alternatives are available. However, since our outcome variable is an ordinal categorical variable these approaches are highly advanced. Since the primary aim of our research was to investigate socio-economic differences in the change in intake frequency and the mediation analyses were only a secondary aim, we decided to choose a simple and straightforward mediation method, like the Baron and Kenny method. Finally, we were not able to investigate whether decreasing fruit and vegetable intake led to replacement by other foods and, if so, which. If fruits and vegetables were replaced by cheaper, unhealthier foods, the impact on dietary quality will be negative, whereas if they were replaced by cheaper, healthier foods such as legumes, the effect will not be necessarily negative.

Conclusion

In conclusion, during a period of economic crisis, relative differences in intake of fruits and vegetables between lower and higher income and education groups widened. This is partly explained by the perception that fruits and vegetables are expensive and the experience of financial distress among the lower income and education groups. To obtain a comprehensive picture of this complex problem, future research should further investigate the underlying mechanisms of socio-economic differences in dietary intake over time. In addition, as the effects of the economic crisis on dietary intake have only recently become apparent, it is important to monitor the occurrence of unhealthy dietary intake and/or barriers to making healthy dietary choices in lower socio-economic groups.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The GLOBE study is carried out by the Department of Rotterdam of the Erasmus University Medical Centre in Rotterdam, in collaboration with the Public Health Services of the city of Einhoven and region South-East Brabant. The authors are thankful to Eris Eekhout for her support on the imputation of missing values. Financial support: The present project was financed by grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw project number 40050009 and ZonMw Healthy Food Program, project number 115100006). The funder had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. Authorship: S.C.D. performed the statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. J.E.N., I.A.B. and M.V. had critical input in the data analyses and helped drafting the manuscript. C.B.M.K. was involved in the data collection and design of the questionnaire, had critical input in the data analyses, and helped drafting the manuscript. F.J.v.L. is the principal investigator of the GLOBE study, coordinated data collection, had critical input in the data analyses, and helped drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was approved by the appropriate ethics committee and therefore performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017004219