Inadequate eating habits are responsible for more deaths than any other global risk factor, including smoking(Reference Afshin, Sur and Fay1). National nutritional surveys show that most people do not follow dietary recommendations, which is one of the reasons for the high prevalence of obesity and other chronic diseases(Reference Polhuis, Vaandrager and Soedamah-Muthu2).

In order to understand eating behaviour contrary to dietary recommendations, it is essential to consider the environment that involves the formation of eating habits – physical, social, emotional and cultural aspects. In this sense, the Salutogenic Theory, which seeks to explain the interaction of the different systems involved in maintaining full health, has gained more and more followers(Reference Mittelmark, Sagy and Eriksson3).

Conversely, the traditional biomedical view does not value the psychosocial and sociocultural factors involved in this process and can therefore be considered reductionist. Health professionals generally work within a biomedical paradigm in which taking care of someone’s diet is seen as an individual and not a collective responsibility. Diets depend on compliance with national dietary guidelines: not drinking alcohol, reducing the intake of foods containing saturated fats, sugars and salt, and, on the other hand, increase the intake of foods containing unsaturated fat and fibre (fruits, vegetables and grains)(Reference Swan, Bouwman and Aarts4).

Studying people and the context in a disjointed way, as does the traditional biomedical view, may be easier, but it does not do justice to reality and limits relevance and applicability in everyday eating situations. Aaron Antonovsky’s Salutogenic Theory, therefore, has filled the gap left by the traditional biomedical view, by seeking to understand primarily the factors associated with health and well-being, from the biopsychosocial point of view, and to explain what are the necessary resources to guarantee the development of an adequate human diet(Reference Mittelmark, Sagy and Eriksson3).

The Salutogenic structure adds two features to the current biomedical approach. First, it considers all aspects of health, considering health not only as the absence of disease, but also as a quality of life and well-being. Second, it aims to answer the question of how health arises from active participation in lifelong learning experiences. The use of this guidance to study the dynamic interaction between the individual and the context provides a better understanding of how people themselves create health, thus generating a future basis for changes in quality of life strategies(Reference Swan, Bouwman and Hiddink5).

To assess the interaction between people and their context, Aaron Antonovsky created within his theory the concept of the sense of coherence (SOC). SOC is a global orientation that expresses the penetrating, long-lasting, trusting, predictable and explainable feelings of the individual; the resources that are available to meet the demands placed on stimuli and helps to assess if these demands are challenges worthy of investment and engagement. SOC is considered a source of resilience and guidance to protect the well-being of life. This instrument is easy to apply and operationalise in the dynamic interaction between the three subcomponents of understandability, manageability and significance(Reference Antonovsky6). One of its limitations is that some studies report respondents’ difficulties in understanding some items and the origin of these problems may be cultural differences. To minimise this limitation, cross-cultural adaptations, modifications in some questions of the scale are carried out, and these versions are evaluated and validated(Reference Scalco, Abegg and Celeste7). SOC is measured through a questionnaire of twenty-nine questions (full version) or thirteen questions (short version), with seven or five answer options, both formulated by the creator of the theory. A strong SOC is defined as a direction that helps people to perceive life as comprehensive, manageable and meaningful in order to reduce perceived tension(Reference Antonovsky6).

Since salutogenesis guides the study of health as an interaction between physical, mental, social and spiritual factors, portraying the way people experience food and health in their daily lives, research on salutogenic nutrition has the potential to lay the basis for strategies that emphasise resources to maintain a healthy diet(Reference Swan, Bouwman and Hiddink5).

In view of the above, the objective was to systematically review empirical studies to assess the relationship between the SOC, behaviour/eating habits and nutritional status, based on the theoretical and conceptual basis of the Salutogenic Theory.

Methods

This is a systematic literature review study, carried out between May and November 2020, in order to answer the following question: ‘Is the SOC associated with nutritional status and/or eating behaviour?’ The adopted protocol followed the items established by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols (PRISMAP)(Reference Moher, Shamseer and Clarke8,Reference Shamseer, Moher and Clarke9) and was registered in the PROSPERO database (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/), through the number CRD42020191179.

Two researchers (GV and BP) independently carried out the searches in the following databases, from inception to November 2020: MEDLINE/PubMed, Science Direct/Elsevier, LILACS/Bireme, SciELO and Google Scholar. For the MEDLINE/PubMed database, indexed terms in the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were used and for LILACS/Bireme and Scielo databases, indexed terms in the Health Sciences Descriptors (DeCS) were used. The search terms were related to the Salutogenic Theory, nutritional status and eating behaviour: ‘Salutogenesis’, ‘Sense of coherence’, ‘Nutritional Science’, ‘nutritional status’, ‘feeding behavior’ and ‘healthy eating’. These terms were used in English and Portuguese languages, according to the database searched. The Boolean operators ‘AND’ and ‘OR’ were used to cross search terms and define the search strategy.

Observational studies of the cohort, case–control and cross-sectional design were included, involving the population of adults (age range 18 to 60 years) and the elderly (age range> 60 years) of both sexes and who used SOC as the exposure variable. There was no restriction on language or year of publication for the inclusion of the studies. Duplicate articles in the databases and studies whose population had any mental illness or other associated nature that directly interfered with the SOC were excluded.

The evaluation of the eligibility criteria for inclusion of the studies in the systematic review was carried out by two independent researchers (G.V. and B.P.). First, the studies found in each database were analysed by title and summary to identify potential studies for inclusion. In case of doubts, an evaluation of the full text was made to ensure proper inclusion or exclusion. The full text of the studies judged to be eligible for inclusion was also read in order to confirm the initial screening. When there was disagreement between the two reviewers, the opinion of two other reviewers was asked.

The systematic review description process followed the recommendations for the items in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA). The study data were extracted by two researchers independently (LN and JS) and included title of the study, surname of the first author, year of publication, country where the study was carried out, study design, objective, characteristics of the studied population (age, sex and sample), description of the observation performed and the outcomes studied with their respective assessment instruments, cut-off points, data analysis and results. Disagreement cases were resolved by discussion between the reviewers and the opinion of a third reviewer, if necessary. In case of missing data, the authors of the original articles were contacted to provide more detailed information.

Two independent reviewers carried out the methodological quality assessment of the included articles using the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS). NOS adapted for cross-sectional studies(Reference Herzog, Álvarez-Pasquin and Díaz10) and NOS for cohort studies(Reference Wells, Shea and O’Connell11) were used.

NOS uses a star system for scoring articles, considering specific criteria. Cohort studies could score a maximum of four stars for the selection criteria, two stars for the comparability criteria and three stars for the result criteria, totalling a maximum of nine stars. The authors considered the studies of high quality when they scored ≥7 stars and the moderate quality of 5–6 stars, according to the classification adopted by Xing et al. (2016)(Reference Xing, Xu and Liu12). Regarding cross-sectional studies, a maximum of five stars were scored for the selection criteria, three stars for the comparability criteria and two stars for the outcome criteria, totalling a maximum of ten stars. The criteria adopted by Wang et al. (2017)(Reference Wang, Su and Xie13) were used to classify cross-sectional studies, which considered low-quality scores as 0–4, moderate-quality scores as 5–6 and high-quality scores as ≥7.

The data were presented according to the nutritional development outcomes: nutritional status and eating behaviour. Eating behaviour was considered as a set of actions related to food, which ranges from the decision to eat, the availability of food, the method of preparation, the utensils used, the schedules and division of meals, and the type of food ingested. Nutritional status, in turn, was considered as the variables related to the energy reserves, usually body fat, and metabolically active mass, usually fat-free mass, of the individuals, being assessed through the assessment of body composition. Body composition may be assessed through a variety of methods, such as anthropometry, the most common, and use of labelled isotopes or bioelectrical impedance, for example.

Results

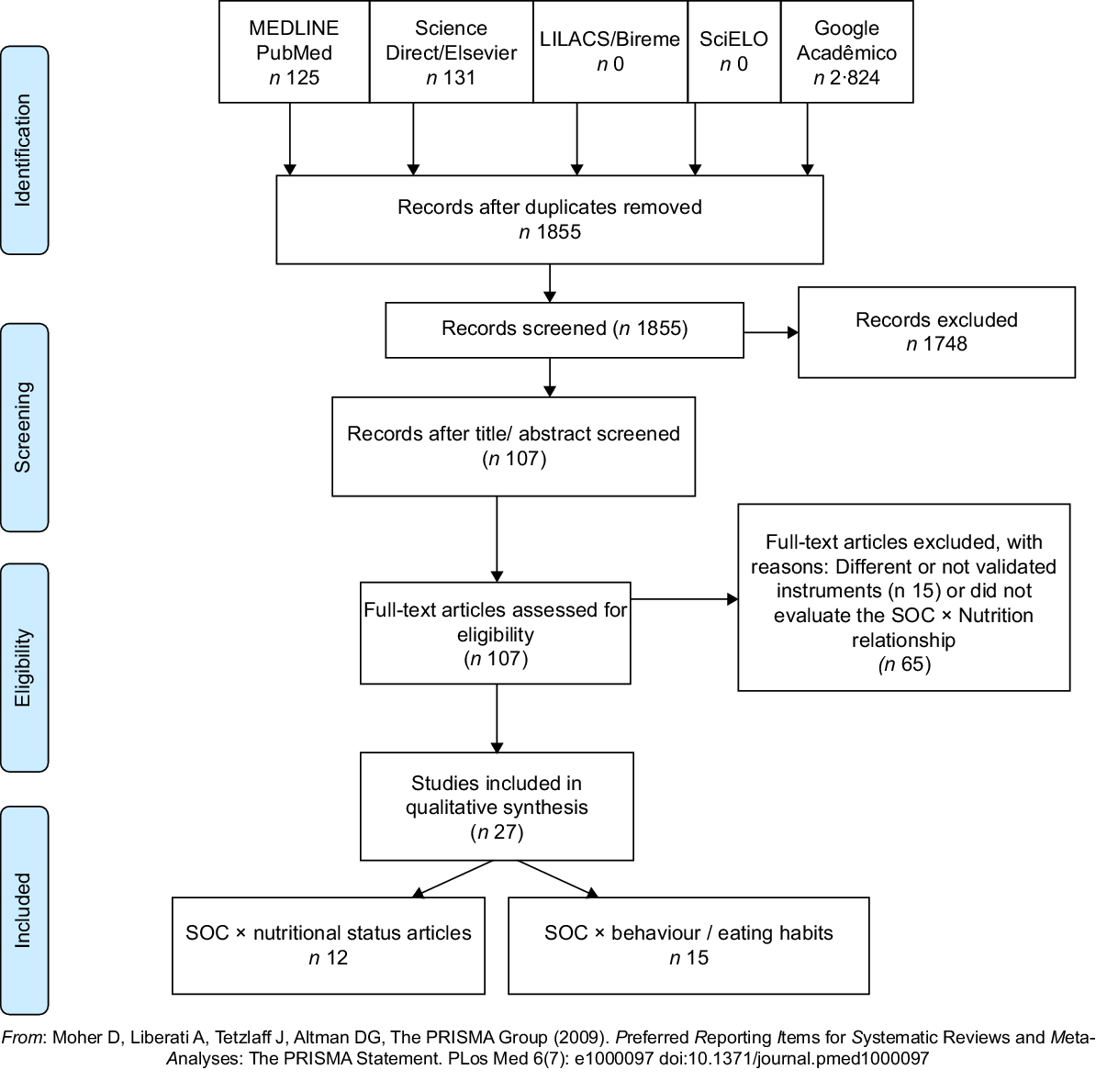

The initial searches in the databases identified 3080 studies, of which 27 met all the eligibility criteria (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Flowchart of the systematic review steps. SOC, sense of coherence

Twenty-five articles were cross-sectional studies and two were cohort studies. The studies were carried out mainly with adults (n 17); a minority included both adults and elderly (n 10). The cumulative sample size of all included studies was 28 981 adults and elderly, aged between 18 and 81 years. The studies were developed in different countries: Japan, Sweden, Germany, USA, Poland, Brazil, Finland, Romania, Australia, Austria, South Korea, Turkey, Hungary, Slovakia and the Netherlands. Most of the articles were in English, being only one in Japanese.

Fifteen studies had eating behaviour/habit as an outcome; twelve had nutritional status. The information presented by the studies analysed was heterogeneous, since they varied in relation to which scale had been adopted to measure the SOC: 71 % used the summary scale with thirteen items and 29 % used the scale with twenty-nine items. The studies also varied in the methods used to assess nutritional status and eating behaviour. Ways of assessing nutritional status varied between Mini Nutritional Assessment in the short form (MNA) and BMI. Eating behaviour/habit was assessed through concepts of adequate nutrition determined by the authors within a pro-health behaviour, consumption of fruits and vegetables, self-perception of a healthy diet, self-reported semi-quantitative food record, consumption of breakfast, sugar consumption between meals, FFQ and dietary scores, based on various indexes. The heterogeneity of the data resulting from these different evaluating methods of the outcomes of interest (nutritional status and eating behaviour) made it impossible to carry out a meta-analysis of the results.

Sense of coherence v. eating behaviour/habit

Among the fifteen articles whose outcome was eating behaviour/habit, eleven demonstrated that SOC positively predicts adequate eating behavior/habit and four indicated that a weak SOC is related to an increase in fast eating, an irregular diet and an excess of food at night supper. Therefore, all articles by different means reported the same relationship: SOC influences eating behaviour/habit (Table 1).

Table 1 Articles that correlate the SOC and eating behaviour/habit

SOC, sense of coherence; SOC-13, sense of coherence summarised with 13 questions; SOC-29, sense of coherence with 29 questions; DEBQ, Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire; EBS, Eating Behavior Scale.

Sense of coherence v. nutritional status

Of the twelve articles that assessed the relationship between SOC and nutritional status, two used MNA as a tool and stated that SOC was weaker in malnourished individuals. A similar positive correlation was found by another article that used BMI as a parameter to assess nutritional status(Reference Sares-Jäske, Knekt and Männistö14). Another six articles showed that SOC and BMI are negatively correlated, that is, the weaker the SOC, the higher the BMI(Reference Sagara, Hitomi and Kambayashi15–Reference Olszak, Nowicka and Baczewska20). On the other hand, three articles found no association between BMI and SOC(Reference Lengerke, Janssen and John21–Reference Redin, Gonçalves and Olinto23) (Table 2).

Table 2 Articles that relate a SOC and nutritional status

SOC, sense of coherence; SOC-13, sense of coherence summarized with 13 questions; SOC-29, sense of coherence with 29 questions.

Methodological quality assessment

All sixteen articles whose outcome was eating behaviour/habit had moderate (n 10) or high (n 6) methodological quality, with scores ranging from 5 to 9 points. The main deficiencies were related to comparability (Table 3). Regarding the twelve articles whose outcome was nutritional status, two articles had low methodological quality(Reference Olszak, Nowicka and Baczewska20,Reference Terelak and Budka22) and the other ten had moderate (n 6) and high quality (n 4). The main deficiencies were also related to comparability (Table 4).

Table 3 Evaluation of the methodological quality of the articles whose outcome was the eating behavior/habit with the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for cross-sectional and cohort studies

*, ** stars for NOS classification.

† Only in the case of cohorts.

Table 4 Evaluation of the methodological quality of the articles whose outcome was nutritional status using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for cross-sectional and cohort studies

*, ** stars for NOS classification.

† Only in the case of cohorts.

Discussion

When analysing the selected articles, fifteen studies asserted that the SOC positively influences eating behaviour, where a strong SOC was associated with several healthy eating patterns. On the other hand, the results of the twelve studies that assessed the relationship between the SOC and nutritional status were controversial.

Research on salutogenic nutrition, the theoretical basis of the SOC, has the potential to bring new insights on health promotion. Salutogenic nutrition guides the study of the dynamics between people and their environment with respect to how health develops from this interaction(Reference Polhuis, Vaandrager and Soedamah-Muthu2). Evidence shows that a strong SOC is associated with a number of behaviours related to a healthy lifestyle, including, among others, healthier eating patterns, physical activity, better oral health behaviours and not smoking(Reference Swan, Bouwman and Hiddink5,Reference Hassmen, Koivula and Uutela24,Reference Lindmark, Stegmayr and Nilsson25) .

Hence, it is worth noting that a healthy diet goes beyond a nutrient-balanced diet, also encompassing the structure and regularity of the eating habit, the way of preparing food and the psychosocial well-being. Thus, having a fixed number of meals at fixed or routine times and enjoying food with the family, for example, are aspects related to healthy eating(Reference Lundkvist, Fjellstrom and Sidenvall26,Reference Bisogni, Jastran and Seligson27) .

Based on this concept, it is already known that stressful situations contribute to abnormal diet patterns. According to Kye & Park (2012)(Reference Kye and Park28), SOC plays a significant role in the perception of a healthy diet. Thus, when the food was evaluated according to emotional, external and food restriction scales, a lesser SOC and more restricted food were predictors of emotional tension. Therefore, it is possible to claim that people who cannot cope with stress tend to have an emotional eating behaviour, eating quickly and with food restriction, that will generate excessive consumption(Reference Greimel, Kato and Müller-Gartner29–Reference Kato, Greimel and Hu31). People who resist the negative effects of stress tend to eat healthy diets.

Eating is highly contextual, and personal interpretations of healthy eating are complex and diverse, as they reflect personal, social, cultural and environmental experiences(Reference Bisogni, Jastran and Seligson27). Eating practices are also inserted in a temporal context. Past experiences guide how people make food choices in the future(Reference Devine32). Thus, a weak SOC is related to the development of inappropriate eating behaviours/habits over time. From another point of view, studies concluded that the SOC contributes independently to explain the variations in the intake of vegetables and fruits and in the intake of saturated fat, sucrose and sweets(Reference Lindmark, Stegmayr and Nilsson25,Reference Peker, Bermek and Uysal33,Reference Koponen, Simonsen and Suominen34) . Mediating factors such as the availability and accessibility of fruits and vegetables at home, nutrition and intake of fruits and vegetables, and irregular eating patterns explain the SOC association and intake of nutrient-rich foods(Reference Ray, Suominen and Roos35).

Hence, people with a strong SOC have an orientation towards healthier lifestyle behaviours, which includes a healthier diet, corroborating the findings of studies that evaluated the relationship between SOC and eating behaviour(Reference Swan, Bouwman and Hiddink5,Reference Sagara, Hitomi and Kambayashi15,Reference Lindmark, Stegmayr and Nilsson25,Reference Kye and Park28–Reference Kato, Greimel and Hu31,Reference Peker, Bermek and Uysal33–Reference Pusztaia, Rozmanna and Horvátha41) .

If a strong SOC influences a balanced and healthy diet, it would be also expected to be correlated with an adequate nutritional status. The articles that correlated SOC with nutritional status, however, showed conflicting results. The mechanisms involved in the regulation of body weight in humans include genetic, physiological and behavioural factors. These factors can contribute to a positive energy balance, leading to body weight gain. It has been reported that SOC is strongly related to aspects of negative emotionality, and negative emotionality, in turn, is associated with a higher BMI and weight gain. Based on this correlation, some of the selected studies showed a relationship between a higher BMI and a weak SOC, portraying the reduction of stress resilience as a potential important factor of obesity(Reference Sagara, Hitomi and Kambayashi15,Reference Skär, Juuso and Söderberg17–Reference Olszak, Nowicka and Baczewska20) . Contrary to this point of view, Zugravu (2012)(Reference Zugravu16) observed that higher levels of BMI were associated with a high SOC score. This result, which is not in line with the literature, was seen by the author as a limitation inherent to the design of a cross-sectional study.

Another three studies associated a lower SOC with a lower BMI and even malnutrition(Reference Sares-Jäske, Knekt and Männistö14,Reference Dewake, Hamasaki and Hitoshi42,Reference Dewake, Hamasaki and Sakai43) . Another three studies found no association between SOC and BMI, stating that SOC, that is, the ability to deal with stresses and to solve problems, does not influence nutritional status(Reference Lengerke, Janssen and John21–Reference Redin, Gonçalves and Olinto23). Many of these studies with contradictory results did not have this association as the main objective to be studied and others had a very small number of participants. Perhaps for these reasons, due attention and explanation of these findings were not given.

Thus, it can be observed that the relationship between SOC and nutritional status was different in the various studies, even being absent in some studies. Possibly, this could be because studies carried out to date have had a cross-sectional design, which limits some conclusions, or their line of thinking was not adequate, which can be noted by the low and moderate methodological quality of most of these articles.

Limitations

The heterogeneity both in the way of evaluating the nutritional data and in the data brought by the selected articles was an important limitation, which made it impossible to carry out a meta-analysis. The methodological quality of the articles, mostly moderate and low, also proved to be a limitation of the review, demonstrating the need for more studies with better quality that portray this association.

Conclusion

SOC had a positive relationship with several healthy eating behaviours. Based on these findings, it would be interesting to use SOC for the early detection of protective factors for healthy eating habits (by identifying a strong SOC), thus adopting the instrument as a screening in public health care, enabling early and targeted interventions. Therefore, research institutions should develop interventions that strengthen people’s SOC as a means of improving eating behaviours. On the other hand, intervention studies for follow-up over a longer time and in different cultures should be developed in order to better establish the relationship between SOC and nutritional status, which was inconsistent among the studies.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Sidney Pratt who revised the English text of this paper, Canadian, MAT (The Johns Hopkins University), RSAdip – TESL (Cambridge University).

Financial support:

This review had no external funding, and all funding was from the authors themselves.

Conflict of interest:

There are no conflicts of interest.

Authorship:

G.R.S.V. participated in the formulation of the research question, study design, realisation of the study, data analysis and writing of the article; B.M.P. participated in the realisation of the study, data analysis and writing of the article; N.B.B. participated in the data analysis and writing of the article; J.R. L.S. participated in the realisation of the study; L.F.N. participated in the realisation of the study; T.M.M.T.F. participated in the writing of the article; M.D.C.L. participated in the writing of the article.

Ethics of human subject participation:

This study did not involve human participants.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021004444