Identifying healthy lifestyles such as proper nutrition is critical to lessen the burden of chronic disease and related risk factors. Lifestyle interventions among middle-aged and older adults may be complex and may have differing effects based on social support. Thus, an investigation of determinants that may lead to one’s healthy lifestyle is important. For example, lifestyle factors play a substantial role in the prevention and management of chronic diseases such as CVD, obesity and type 2 diabetes, which are prevalent at substantial rates in middle-aged and older adults(Reference Benjamin, Muntner and Alonso1–Reference Flegal, Kruszon-Moran and Carroll3). About 20 % of adults aged ≥65 years die of CVD, and one-third of deaths relating to CVD occur among those under 75 years of age(Reference Benjamin, Muntner and Alonso1). According to a 2019 report, the United States spent approximately US$351 billion on the medical costs of CVD and stroke in 2014–15, and the cost is projected to increase for middle-aged (45–64 years) and older (≥65 years) adults in the future(Reference Benjamin, Muntner and Alonso1). Furthermore, the growing prevalence of obesity among older adults is prominent; more than one-third of adults aged ≥60 years (37·5 % for men and 39·4 % for women) are obese(Reference Flegal, Kruszon-Moran and Carroll3), increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes(Reference Abdullah, Peeters and de Courten4). Thus, multimorbidity among middle-aged and older populations has increasingly become a public health concern.

For the prevention and management of chronic disease, the importance of healthy eating habits, in addition to regular physical activity, has been emphasised(Reference Shlisky, Bloom and Beaudreault5). Certain dietary patterns, such as the Mediterranean and plant-based diets, for example, are associated with reduced risk for CVD(Reference Hung, Joshipura and Jiang6,Reference Ellingsen, Hjerkinn and Seljeflot7) , cognitive decline(Reference van de Rest, Berendsen and Haveman-Nies8–Reference Kesse-Guyot, Andreeva and Jeandel10), type 2 diabetes(Reference Jannasch, Kröger and Schulze11–Reference Schwingshackl, Missbach and König13) and depression(Reference Lai, Hiles and Bisquera14), as well as enhanced quality of life(Reference Govindaraju, Sahle and McCaffrey15). However, the intake of fruit/vegetables among older adults is sub-optimal(Reference Nicklett and Kadell16). Only 10·9–12·4 % of adults aged ≥51 years consume the recommended amount of fruit and vegetables to meet federal recommendations(Reference Lee-Kwan, Moore and Blanck17). To reduce the risk of developing and accelerating chronic diseases, additional attention should be paid to factors that facilitate healthy dietary habits.

As a critical factor relating to health behaviour, research shows the influence of social relationships on dietary intake. Social isolation has been reported to increase the risk of poor nutrition(Reference Locher, Ritchie and Roth18–Reference Conklin, Forouhi and Surtees21), while social support may help support healthy dietary behaviour of older adults(Reference Conklin, Forouhi and Surtees21–Reference Bloom, Edwards and Jameson24). For instance, an analysis of adults aged ≥50 years in the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer (EPIC) study identified an association between being widowed or living alone and low levels of vegetable intake, and this relationship was more profound among men compared with women(Reference Conklin, Forouhi and Surtees21). Those with less frequent contact with friends had lower fruit/vegetable intake. Similarly, the association between poor diet intake and living alone was reported in a study of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III data.(Reference Davis, Murphy and Neuhaus25) A focus group study of community-dwelling older adults in the UK also pointed out the positive influence of social engagement (e.g. social activity and social interaction with friends and family) on dietary habit(Reference Bloom, Lawrence and Barker26). A study of community-dwelling older adults in the UK(Reference Bloom, Edwards and Jameson24) found that men and women who had emotional support had a better diet, which was measured by a FFQ assessing the consumption of twenty-four foods like fruit, vegetables, wholegrain cereals and oily fish. Practical support was associated with healthy eating among older men, while a larger social network was more critical among older women(Reference Bloom, Edwards and Jameson24). Findings of these previous studies are mostly based on cross-sectional analysis(Reference Vesnaver and Keller23). Additionally, the concept of social support for a healthy diet has been predominantly captured by indirect measures, such as the number of friends; friendship density(Reference McIntosh, Shifflett and Picou22); frequency of social(Reference Sahyoun, Zhang and Serdula20), family and friend(Reference Conklin, Forouhi and Surtees21) contact; and the availability of emotional, practical and negative aspects of support in general(Reference Bloom, Edwards and Jameson24,Reference Stansfeld and Marmot27) . Limited studies have assessed social support directly relating to dietary intake, such as companionship – having meals together (e.g. refs. Reference Boulos, Salameh and Barberger-Gateau19 and Reference McIntosh, Shifflett and Picou22) and helping with cooking(Reference McIntosh, Shifflett and Picou22). The role of social support specific to healthy eating among older adults has been understudied.

Intervention

To help lessen extant research gaps, the current study examined the role of social support on dietary intake among older adults who participated in a lifestyle intervention designed to improve eating habits and physical activity, Texercise Select (Reference Ory, Smith and Howell28). Texercise Select is a 10-week group-based programme designed for adults aged ≥45 years. The programme was designed to encourage healthy eating and physical activity through education, discussions and training exercise(Reference Ory, Smith and Howell28). Led by trained facilitators who go through 6 h of standardised training, this programme uses an official programme manual and other complementary materials. The programme delivers a total of twenty sessions (i.e. two 1·5-h sessions each week for 10 weeks), and about a half of the workshops were devoted to discussions and activities about healthy eating. In each session, programme participants discuss healthy eating and behaviour changes, such as goal-setting for healthy eating, nutrition facts, how to read food labels, behaviour tracking and problem-solving in a group setting.

The programme was designed to help participants gain different behavioural skills through hands-on practice and discussions about how to overcome barriers and meet goals associated with healthy eating. The effectiveness of Texercise Select has been reported: improved fruit/vegetable intake per week(Reference Smith, Ory and Jiang29,Reference Smith, Lee and Towne30) , fast-food intake per week(Reference Smith, Lee and Towne30), daily water intake(Reference Smith, Ory and Jiang29,Reference Smith, Lee and Towne30) , physical activity(Reference Smith, Ory and Jiang29,Reference Ory, Lee and Han31) and sedentary behaviour(Reference Ory, Lee and Han31). Moreover, programme participants improved the level of social support for physical activity(Reference Ory, Lee and Han31) and dietary intake(Reference Smith, Ory and Jiang29,Reference Smith, Lee and Towne30) .

Aims

Given the relationship between dietary-specific social support and food intake has not been fully explored, the aims of the present study were to: (i) evaluate the psychometrics of the dietary-specific social support scale included in the current study, the Social Support for Healthy Eating Scale; and (ii) test if improved dietary-specific social support mediates the intervention effect on changes in dietary intake among Texercise Select participants.

Methods

Participants and study procedure

Data were collected from middle-aged and older adults who resided in Texas and who were recruited from various community sites between May 2015 and Aug 2017. Participants were recruited through various community-based organisations for older adults and healthcare centres that provide health and wellness programmes to older adults in Texas(Reference Ory, Lee and Han31). While the research team approached and recruited participants who have similar characteristics, the intervention and comparison groups were not randomly assigned due to the pragmatic nature of the community-based intervention. Group assignment was determined based on the need and preference of participating sites. For the intervention group, Texercise Select workshops were delivered in community settings such as senior centres, senior housing, community centres and faith-based facilities. Texercise Select was not delivered to the comparison group, although the participants in this group might have been exposed to other health and wellness programmes. The current study used data from 386 middle-aged and older adults (intervention n 211, comparison n 175) who completed pre- and post-surveys.

Dietary intake

Information about dietary intake was collected using four items(Reference Smith, Ory and Jiang29). Participants were asked to answer the question, ‘Over the past 7 days, how many times did you eat fast food, meals or snacks?’ using a six-point scale: ‘0’, ‘1’, ‘2’, ‘3’, ‘4’ and ‘≥5’. Using the same response scale, the following three questions were asked: ‘Over the past 7 days, how many servings of fruit/vegetables did you eat each day?’ and ‘Over the past 7 days, how many soda and sugar-sweetened drinks (regular, not diet) did you drink each day?’ Daily water intake was assessed with the item ‘In the average day, how many cups of water do you drink each day?’ using a nine-point scale, ranging from ‘0’ to ‘≥8’. Change scores between pre- and post-survey values were derived by regressing post-survey values on pre-survey values.

Dietary-specific social support

The current study used an original Social Support for Healthy Eating Scale to assess changes in dietary-specific social support. Participants rated how often they receive social support by assessing the following three specific social support goals for dietary activities: ‘plan dietary goals’, ‘keep dietary goals’ and ‘reduce barriers to healthy eating’. The perceived availability of dietary-specific social support was reported using a four-point scale with categories of ‘never’, ‘rarely’, ‘sometimes’ and ‘often’. Similarly, we computed the change scores between pre- and post-survey values by regressing post-survey values on pre-survey values. In Texercise Select, participants discuss how to plan and keep goals as well as remove barriers to healthy eating in a group setting. This scale consisting of three items relating to workshop discussion topics was used to evaluate programme effectiveness – whether participants improved levels of dietary-specific social support as a result of Texercise Select workshop participation. While having reported the internal consistency of the scale (i.e. Cronbach’s α) in the previous studies(Reference Smith, Ory and Jiang29,Reference Ory, Lee and Han31) , this is the first study that investigated the reliability and validity of the scale.

Sociodemographic information

Participants’ sociodemographic information collected by the questionnaire included age, sex, living arrangement, race, chronic conditions and education. Age (number of years), sex (female = 1, male = 0), race (white = 1, non-white = 0), education (0 = less than some high school, 1 = some high school, 2 = high school graduate, 3 = some college or vocational school, 4 = college graduate or higher), number of chronic conditions (self-reported), living arrangement (living alone = 1, living with someone = 0) were entered as covariates in the mediation analysis.

Participants selected their race from the categories of White, Black or African American, Asian, American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and other. Another item assessed their ethnicity (Hispanic/Latino = 1, non-Hispanic/Latino = 0). Because a vast majority (90·0 %) of participants reported being non-Hispanic/Latino, we elected to use race (and omit ethnicity) from study analyses to facilitate meaningful comparisons. Since a vast majority of our analytic sample were either White (50·0 %) or Black or African American (46·5 %) (i.e. 3·6 % for Asian or other), a binary race category (i.e. White or Non-white, which includes Black or African American, Asian, American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander and other) was created and used for analyses.

Participants were provided a list of chronic conditions and asked to self-report that they had been diagnosed with by a healthcare provider. The list included arthritis/rheumatic disease, breathing/lung disease (e.g. asthma, emphysema and bronchitis), cancer, depression or anxiety disorder, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension and stroke. The number of chronic conditions was derived from the sum of endorsed conditions from this self-reported list.

Food access was reported as a factor relating to dietary intake among older adults(Reference Sharkey, Johnson and Dean32); therefore, we also included geographic residence as a covariate using the 2013 National Center for Health Statistics’ Urban–Rural Classification Scheme for the Counties of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention(Reference Ingram and Franco33). This coding scheme consists of six levels based on: (i) metropolitan statistical areas (MSA) and micropolitan statistical areas defined by the Office of Management and Budget, (ii) the population size of MSA and (iii) the location of city populations in the largest MSA with ≥1 million(Reference Ingram and Franco33). In the current study, we created two geographical groups: large/medium metro (codes 1–3) and small metro/micropolitan/non-core (codes 4–6) counties. Based on this coding scheme, each participant’s residence by county level was coded as ‘1’ for large/medium metro and ‘0’ for small metro/micropolitan/non-core.

Data analysis

Basic between-group comparisons

Sociodemographic characteristics and chronic conditions were compared between intervention and comparison groups using a χ 2 test for categorical variables and a Mann–Whitney U test for skewed continuous or ordinal variables.

Attrition analyses

We performed an attrition analysis to assess whether there were significant differences in sociodemographic characteristics between the participants who completed the pre- and post-surveys after the programme and those who did not.

Scale evaluation

We performed an exploratory factor analysis to examine whether the three items of the dietary-specific social support measured the same construct using data from the study participants who completed the pre-survey (n 564). In addition to bivariate correlations for the identification of possible multicollinearity, sampling adequacy (Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin [KMO] value > 0·5) and Bartlett’s test for patterned relationships ( P < 0·05)(Reference Kaiser34) were assessed. We then examined the reliability and validity of the dietary-specific social support construct – Social Support for Healthy Eating Scale – using the criteria: Cronbach’s α > 0·7, composite reliability score > 0·7 and average variance extracted (i.e. convergent validity) > 0·5(Reference Fornell and Larcker35).

Total intervention effect

We assessed associations between the intervention condition (1 = intervention, 0 = comparison) and changes in dietary intake, controlling for age, sex, race, number of chronic conditions, living arrangement and geographic residence.

Mediational analysis

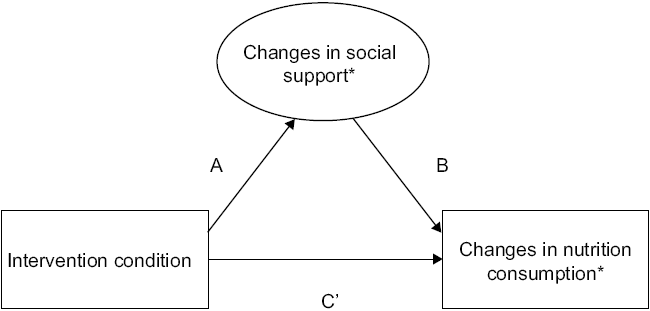

The current study employed structural equation modelling to test if changes in dietary-specific social support mediated the relationship between the intervention condition and changes in dietary intake, controlling for age, sex, race, number of chronic conditions, living arrangement and geographic residence (Fig. 1). For estimating changes in outcome variables and the potential mediator (i.e. dietary-specific social support) over the intervention period, we computed the residualised change scores by regressing post-survey scores on the corresponding pre-survey values(Reference Plotnikoff, Lubans and Penfold36). Maximum likelihood with robust standard error method was used for structural equation modelling since the endogenous variables (i.e. residualised change scores) were continuous and assumed to have non-normal distributions. For mediation testing, we used the bias-corrected bootstrapping method, which has an advantage over the conventional mediation testing method(Reference Baron and Kenny37) for constructing confidence intervals of parameters regardless of the assumption of normal distribution(Reference Shrout and Bolger38). Data were missing completely at random (MCAR) (Little’s MCAR test = 331·45, P = 0·192); thus, we used the Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation method for mediation testing. Exploratory factor analysis and structural equation modelling were performed using SPSS 25 (IBM SPSS Statistics) and Mplus 8 (Muthen & Muthen), respectively.

Fig. 1 The model depicting the mediating role of social support between intervention condition and changes in dietary intake. *Residual change scores obtained based on pre-survey scores as predictors

Results

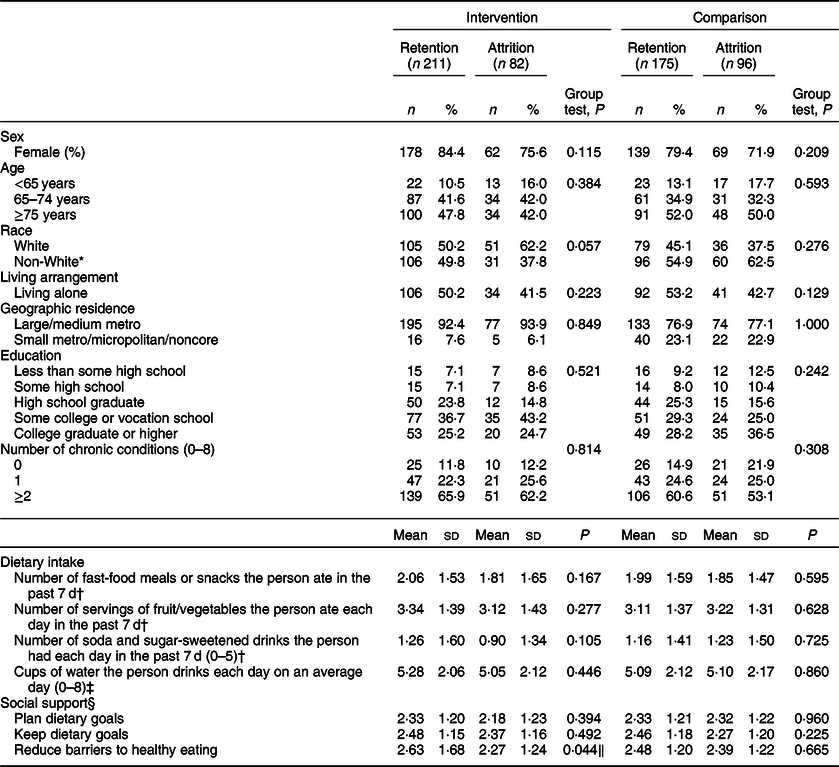

A majority of participants in the intervention and comparison groups were female (81·9 % for intervention, 76·8 % for comparison), ≥75 years (46·2 % for intervention, 51·3 % for comparison), had at least some college or vocation school education (63·6 % for intervention, 58·9 % for comparison) and had ≥2 chronic conditions (64·8 % for intervention, 57·9 % for comparison) (Table 1). About half of older adults lived with someone (52·2 % for intervention, 50·6 % for comparison). The intervention group had a significantly larger proportion of White participants (χ 2 = 7·00, df = 1, P = 0·008) and large/medium metro county residence (χ 2 = 26·89, df = 1, P < 0·001) than the comparison group. No significant difference at pre-survey was found in dietary intake between the intervention and comparison groups. No other items in dietary-specific social support differed between intervention and comparison groups.

Table 1 Sociodemographic and health characteristics, dietary intake and social support of participants at pre-survey by intervention and comparison groups

* Including Black or African American, Asian, American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander and other.

† Six-point scale (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, ≥5).

‡ Nine-point scale (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, ≥8).

§ Four-point scale (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often).

Supplementary analyses showed that among retention and attrition groups, there were no significant differences in sociodemographic, dietary intake or dietary-specific social support, except social support for reducing barriers to healthy eating at pre-survey for the intervention group (z = −0·21, P = 0·044) (Table 2). Among the intervention group, a higher level of social support for reducing barriers to healthy eating was observed in those who completed both pre- and post-surveys.

Table 2 Sociodemographic and health characteristics, dietary intake and social support of attrition and retention by group

* Including Black or African American, Asian, American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and other.

† Six-point scale (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, ≥5).

‡ Nine-point scale (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, ≥8).

§ Four-point scale (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often).

‖ P < 0·05.

Scale evaluation

The acceptable reliability and validity of the dietary-specific social support scale (Social Support for Healthy Eating) was confirmed. Correlations among the three items of dietary-specific social support were moderate to strong (0·57–0·75). No violation of multicollinearity for the construct was confirmed (determinant value 0·23). The obtained KMO value (0·69) indicated an adequate level for factor analysis(Reference Field39). Patterned relationships were also observed among the three items of dietary-specific social support (Bartlett’s test of sphericity: χ 2 = 813·10, df = 3, P < 0·001). The constructs of dietary-specific social support showed high internal consistency with Cronbach’s α (0·86). The obtained values of composite reliability (0·86) and average variance extracted (i.e. convergent validity) (0·68) met the criteria(Reference Fornell and Larcker35).

Total intervention effects

After the intervention period, the intake of fruit/vegetables (B c = 0·52, se = 0·13, P < 0·001) and water (B c = 0·31, se = 0·15, P = 0·041) increased in the intervention group compared with the comparison group, controlling for sex, age, race, education, number of chronic conditions, living arrangement and geographic residence (direct effect) (Table 3). Moreover, living with someone (B = −0·11, se = 0·03, P = 0·002) was associated with changes in fruit/vegetable intake. No significant change was found in the intake of fast-food meals or snacks and soda/sugar-sweetened drinks in the intervention group compared with the comparison group (P > 0·05).

Table 3 Unstandardised path coefficients and significant tests (direct paths) from the structural equation modelling of intervention, social support and dietary intake†

* P < 0·05.

† Each path controlled for age, sex, race, education, living arrangement, number of chronic conditions and geographic residence.

Intervention effects on dietary-specific social support for practicing healthy eating

Participants reported significantly higher levels of dietary-specific social support (B A = 0·28, se = 0·10, P = 0·003) in the intervention group compared with the comparison group after adjusting for sex, age, race, education, number of chronic conditions, living arrangement and geographic residence (direct effect) (Table 3). None of the included covariates were associated with changes in the level of dietary-specific social support (P > 0·05).

Influence of changes in dietary-specific social support on changes in dietary intake

Changes in the level of dietary-specific social support after the intervention period were positively associated with changes in fruit/vegetable intake (B B = 0·27, se = 0·08, P < 0·001) after controlling for sex, age, race, education, number of chronic conditions, living arrangement and geographic residence (direct effect) (Table 3). Living with someone (B = −0·11, se = 0·03, P = 0·002), female sex (B = 0·07, se = 0·03, P = 0·005) and large/medium metro residence (B = 0·06, se = 0·03, P = 0·023) were related to increases in fruit/vegetable intake. No association was found between changes in the level of dietary-specific social support and water intake (P > 0·05). Thus, only the model of fruit/vegetable intake was tested in the subsequent mediating analysis.

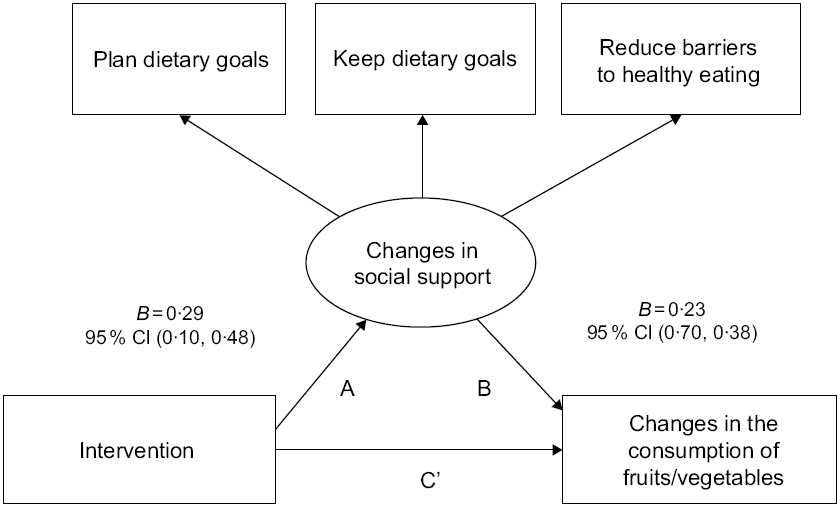

Mediation analysis

The mediating (indirect) effect of changes in the level of dietary-specific social support over the intervention period was confirmed on the relationship between intervention status and increased fruit/vegetable intake among programme participants, after controlling for sex, age, race, education, number of chronic conditions, living arrangement and geographic residence (Fig. 2). Changes in the level of dietary-specific social support mediated (B AB = 0·06, se = 0·02, 95 % CI 0·01, 0·15) the effects of the intervention on fruit/vegetable intake (indirect effect). Thus, the product (B AB) of direct effects fell outside of zero, indicating a significant indirect effect. The explained variance in the indirect effect of dietary-specific social support was 12·0 %. Living with someone (B = −0·10, se = 0·04, P = 0·003) and female sex (B = 0·07, se = 0·03, P = 0·010) were also associated with changes in fruit/vegetable intake. Regarding the dietary-specific social support items, keeping dietary goals (β = 0·93, se = 0·03, P < 0·001) made the strongest contribution in the mediation model, followed by planning dietary goals (β = 0·80, se = 0·03, P < 0·001) and reducing barriers to healthy eating (β = 0·70, se = 0·04, P < 0·001).

Fig. 2 Unstandardised coefficients and bias-corrected bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals for direct and indirect effects from structural equation model testing the mediating (indirect) effect of changes in the level of social support between intervention and changes in fruit/vegetable intake. Note: The model controlled for age, sex, race, education, living arrangement, the number of chronic conditions and geographic residence

Discussion

The current study examined the mediating role of dietary-specific social support in dietary intake among the participants of Texercise Select, a lifestyle intervention. Confirming the appropriate psychometrics of our Social Support for Healthy Eating Scale, we found that improved dietary-specific social support mediated the intervention effect on improvement in fruit/vegetable intake over that intervention period. The indirect (mediation) effect accounted for about 12 % of the overall intervention effect on the increase in fruit/vegetable intake. Moreover, compared with the comparison group, the current study also confirmed that programme participants improved the intake of fruit/vegetables and water as well as their level of dietary-specific social support. The improvement of dietary-specific social support among programme participants was associated with improved weekly fruit/vegetable intake, but not with water intake. These findings suggest that middle-aged and older adults benefitted from this programme by improving fruit/vegetable intake that is partially enhanced by improved dietary-specific social support.

Moreover, we found that living arrangement, female sex and large/medium metro residence were associated with fruit/vegetable intake. Participants who lived with someone improved their fruit/vegetable intake regardless of improvement in dietary-specific social support. These findings suggest that middle-aged and older adults who live with someone may have had more opportunities to apply the healthy eating strategies that were discussed in Texercise workshops (i.e. goal-setting, behaviour tracking and problem-solving for potential barriers) despite the availability of perceived dietary-specific social support.

Previous studies reported consistent findings about the association between living arrangement and the risk of poor dietary intake among middle-aged and older adults(Reference Davis, Murphy and Neuhaus25,Reference Sharkey, Johnson and Dean32,Reference Davis, Murphy and Neuhaus40) . A secondary data analysis using the Nationwide Food Consumption Survey(Reference Davis, Murphy and Neuhaus40) reported the risks of unhealthy eating behaviours among older adults who live alone, such as skipping meals (especially breakfast) and a higher proportion of calorie intake from eating outside of home. An association of living alone with a lower intake of fruit and vegetables was also confirmed in the study that examined the distance for a good selection (fresh or/and processed) of fruit or vegetables among older adults in rural areas(Reference Sharkey, Johnson and Dean32). Furthermore, a study of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III data reported that living alone was associated with poor diet quality among middle-aged and older adults(Reference Davis, Murphy and Neuhaus40).

We found a significant association of living with someone with improved fruit/vegetable intake in this programme evaluation. Our study examined the effect of lifestyle intervention by investigating changes in the dietary intake immediately before and at the end of intervention. The influences of living arrangement on healthy eating among older adults in general as well as in programme evaluation need to be further examined for promoting healthy eating.

We also found that being female was associated with improved fruit/vegetable intake in the mediation model. The findings imply that among female participants of Texercise Select, improvement in fruit/vegetable intake was partially due to improved dietary-specific social support during the workshops. Future studies should examine how female sex plays a role in improving social support for healthy eating. The differential associations of dietary-specific social support with dietary intake by sex have been addressed(Reference Locher, Ritchie and Roth18,Reference Bloom, Edwards and Jameson24) . A larger social network was a factor associated with better diet quality among older women, while the availability of practical support was important among older men(Reference Bloom, Edwards and Jameson24). The lower level of perceived dietary-specific social support was also associated with the risk of poor nutrition among White older women (but not with Black women)(Reference Locher, Ritchie and Roth18). Although differences in dietary-specific social support by race and ethnicity need to be further investigated, the present and previous studies confirmed the differential influences of social relation or support on eating habits by sex.

The current study also identified an association between residing in a large/medium metro area and increased fruit/vegetable intake. This finding can be explained by the ease of access to food resources in large or medium metropolitan areas compared with less-dense small metropolitan or rural areas. A study of food access among older adults in rural areas(Reference Sharkey, Johnson and Dean32) reported that lower levels of fruit and vegetable intake were associated with a longer distance to the nearest supermarket and food stores that sold a variety of fruit and vegetables, after controlling for sociodemographic characteristics and perceived food access. However, in another study, distance to supermarkets in urban areas was not identified as a factor associated with fruit and vegetable intake(Reference Dean and Sharkey41). Inadequate transportation is a known factor influencing limited food choices among rural older adults(Reference Shanks, Haack and Tarabochia42). Thus, our study findings suggest that older adults who reside in large or medium metropolitan areas benefit from the availability of wider food selections, more grocery stores and public transportation. Workshop participants in urban areas may have had more opportunities to obtain healthy foods and apply healthy eating skills because they resided in communities with more resources.

The present study assessed the level of social support directly relating to healthy eating. Similar findings have documented positive associations of social support with dietary intake among older adults, yet they were predominantly based on general social support measures. More specifically, these studies used indirect support measures such as marital status(Reference Locher, Ritchie and Roth18), social contact(Reference Sahyoun, Zhang and Serdula20), social engagement(Reference Johnson, Donkin and Morgan43), friendship network(Reference McIntosh, Shifflett and Picou22), social support in general (i.e. instrumental support, emotional support, social interaction and social space)(Reference Nicklett, Semba and Simonsick44) and adapted social support scales (e.g. the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale for Social Support(Reference Meenan, Mason and Anderson45) and the Close Persons Questionnaire(Reference Stansfeld and Marmot27)). Limited studies have assessed social support specific to dietary behaviours, such as companionship measured by spending meal time together(Reference Boulos, Salameh and Barberger-Gateau19,Reference McIntosh, Shifflett and Picou22) and helping with cooking(Reference McIntosh, Shifflett and Picou22). When assessing diet-related outcomes among participants of a lifestyle intervention that includes components specifically targeting a healthy diet, the use of social support scales directly assessing healthy eating behaviours is critical. For example, Texercise Select participants discuss specific healthy eating strategies, such as goal-setting, proper portion and food labels, in group-based workshops. The direct measure of social support for healthy eating can help identify specific social support associated with improved dietary intake.

Limitations

Several limitations should be noted. First, the current study was conducted without randomisation because of the nature of interventions in community settings. Thus, the estimates of true intervention effects are limited; yet external validity was enhanced in this pragmatic research study(Reference Glasgow46). That said, the current study employed a pre/post case-and-comparison design with an intervention group exposed to the intervention and a comparison group not exposed to the intervention. This is a significant strength beyond a simple pre-post case design. Second, the current study used data from a convenience sample, which may limit the sufficiency of sample size. To compensate for this potential limitation, we employed the bias-corrected bootstrapping method – a non-parametric method of testing indirect effects – in mediation analysis(Reference Shrout and Bolger38). This statistical method allowed us to generate a pseudo-random sample, which may be small or moderate and have an asymmetrical distribution. Third, the geographic scope of the current study was limited (i.e. selected communities in Texas, limited sample distribution preventing a clear rural/urban distinction); therefore, the findings may not be generalisable to the larger population of Texas or that of the nation as a whole. It should also be noted that the focus was on community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults, and may not be generalisable to middle-aged and older adults residing in an institutionalised setting. Fourth, the current study utilised self-report information; thus, risk of errors, such as recall bias and social desirability bias, could not be avoided(Reference Althubaiti47). A recall error could influence the association between dietary-specific social support and dietary intake. It should be also noted that there is a possibility that self-report data could be influenced by one’s social desirability or acceptability, despite the current study addressing anonymity and confidentiality during data collection.

A relatively large proportion of participants did not complete post-survey (28·0 % for intervention, 35·4 % for comparison). To minimise potential bias due to attrition, we performed attrition analysis to investigate sociodemographic and health status differences. We adjusted the analyses for race, which significantly differed between completers of pre- and post-survey and non-completers when performing structural equation modelling (in addition to age, sex, education, living arrangement, number of chronic conditions and geographic residence). Moreover, we had imbalanced data in the sex variable with a large proportion (80·0 %) of female participants typical of community-based health promotion programmes. Thus, our findings about the association between being female and having increased fruit/vegetable intake may require a careful interpretation for generalisability. Given the distribution of this variable, we acknowledge the limited sensitivity to detect true associations of being male with the selected variables.

Additionally, some other confounding factors might be associated with changes in dietary intake. For instance, we included the geographic residence of participants by county level, yet other environmental- and neighbourhood-level factors relating to food access, such as the availability of transportation and stores with healthy food selection(Reference Sharkey, Johnson and Dean32), were not included in the present study. We also chose a proxy measure of socioeconomic status, participants’ educational levels v. using income levels. This decision was made based on the fact that a large proportion of missing values in income levels (19·4 %) were identified along with a moderate level of correlation between educational and income levels (r 0·45, P < 0·001). We decided to use participants’ education levels as a proxy measure of income levels in the current study because we did not have other wealth-related information available for participants.

Implications

The current study suggests valuable practice and research implications. Participants of Texercise Select, which stresses engagement through discussions and activities for goal-setting and problem-solving, improved dietary-specific social support for healthy eating measured over the programme period. The improved dietary-specific social support was partially related to increased fruit/vegetable intake among participants over time. Thus, this group-based lifestyle intervention, which can facilitate social support for developing various healthy eating skills, may be beneficial for improving dietary behaviours among middle-aged and older adults. While the current study specifically examined Texercise Select, it is plausible that other group-based interventions that facilitate the development of practical skills through engagement (e.g. disease self-management) for older adults may be capable of improving dietary-specific social support and enhancing intended programme outcomes. Future research should investigate additional social support strategies for healthy eating. Such efforts would be beneficial for identifying workshop activities towards enhancing social support for healthy eating.

Conclusion

Middle-aged and older adults who participated in Texercise Select improved their dietary intake of weekly fruit/vegetables and daily water intake as well as the level of dietary-specific social support compared with the comparison group. The improved level of dietary-specific social support among programme participants was associated with improved weekly fruit/vegetable intake. No association was found between the improved level of dietary-specific social support and an increase in daily water intake. Furthermore, the intervention effect on improved weekly fruit/vegetable intake was mediated by an improved level of dietary-specific social support among programme participants, suggesting that Texercise Select may have helped improve their fruit/vegetable intake by increasing the levels of dietary-specific social support. Living with someone and being female were also associated with an improved intake of fruit/vegetable intakes. Designing a lifestyle intervention to promote social support for developing healthy eating skills may be critical to improving food intake among middle-aged and older adults. This, in turn, can promote healthy aging and reduce the onset and progression of chronic diseases.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors recognise the Texas Health and Human Services Commission for supporting the creation and evaluation of Texercise Select, and the Texas A&M School of Public Health for helping to standardise and implement Texercise Select. We thank the delivery sites, class facilitators and participants for their role in the study. Financial support: None. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: A.Y. conceived research questions. A.Y. wrote the draft with M.L.S. and M.G.O. SL handled data acquisition and management. A.Y. performed statistical analyses. S.L., S.D.T., M.L.S. and M.G.O. provided critical revisions and feedback. All authors approved the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Texas A&M University Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.