The literature evidence indicates that moderate alcohol consumption is associated with a lower risk level for a number of cardiovascular risk factors such as lipoprotein, glucose metabolism, haemostatic and inflammatory markers in the elderly(Reference Perissinotto, Buja and Maggi1). Accordingly, a J-shaped relationship between alcohol consumption and risk for CHD morbidity and mortality is broadly reported in elderly persons(Reference Mukamal, Chung and Jenny2). Several prevalence and longitudinal studies have shown that the well-known age-dependent renal decline is strongly associated with cardiovascular risk factors in the elderly(Reference Sarnak and Levey3), but to date the relationship between alcohol consumption and renal function is still unclear.

The abuse of alcohol is known to be associated with renal alterations, including tubular dysfunction, acute tubular necrosis and IgA nephropathy(Reference De Marchi, Cecchin and Basile4). However, scarce evidence has been provided on a role of moderate alcohol consumption on kidney function in adults. A recent study on 65 601 middle-aged Chinese men suggested an inverse relationship between alcohol consumption and the risk of end-stage renal disease(Reference Reynolds, Gu and Chen5). In another large prospective cohort study, Schaeffner et al. reported an inverse relationship between alcohol consumption and the risk of renal dysfunction in apparently healthy men(Reference Schaeffner, Kurth and de Jong6). A prospective observational study on nurses found no significant association between alcohol consumption and the onset of renal dysfunction(Reference Knight, Stampfer and Rimm7) in women. In addition, in the second National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, alcohol was unrelated to any presence of chronic kidney disease in 9082 adults(Reference Stengel, Tarver-Carr and Powe8). On the other hand, in a case–control study Perneger et al.(Reference Perneger, Whelton and Puddey9) found that consumption of two alcoholic drinks daily corresponded to a fourfold increase in the risk of end-stage renal disease, whereas a case–control study by Vuppituri and Sandler(Reference Vupputuri and Sandler10) identified no increased risk of chronic kidney disease among regular alcohol consumers. While the association between alcohol consumption and renal function in adult populations is still under debate, information on elderly populations is lacking(Reference Menon, Katz and Mukamal11).

The aim of the present longitudinal study was to investigate the association between alcohol consumption and prevalence and incidence of renal function impairment in an elderly population. The study considered a representative sample of an elderly Italian population, for whom alcoholic beverages are traditionally part of the diet.

Methods

Study sample

Our sample population was drawn from the Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging (ILSA) cohort. The ILSA is a population-based longitudinal study on the health of Italians aged 65–84 years. The main aims of ILSA were to study the prevalence and incidence rates of common chronic conditions (IHD, hypertension, congestive heart failure, arrhythmia, intermittent claudication, type 2 diabetes mellitus, impaired glucose tolerance, thyroid dysfunction, dementia, parkinsonism, stroke and peripheral neuropathy), to assess physical and mental functional status in the older population, and to identify their risk factors and protective factors. A random sample of 5632 individuals was identified using the demographic lists at the registry offices of eight Italian municipalities from a total target population of 44 737 individuals. The full design of the ILSA has been published elsewhere(Reference Maggi, Zucchetto and Grigoletto12). In brief, the study included prevalence and incidence surveys. The first survey started in March 1992 and the second in September 1995, with a mean follow-up of 3·5 years. Each survey consisted of two phases: a screening phase for all participants, which included a personal interview, a physical examination, and laboratory and diagnostic tests; and a second phase for participants who tested positive for one or more diseases, who underwent a clinical assessment by board-certified physicians (geriatricians or neurologists) and a review of their medical records. Informed consent was given according to institutional guidelines. All of the study phases were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

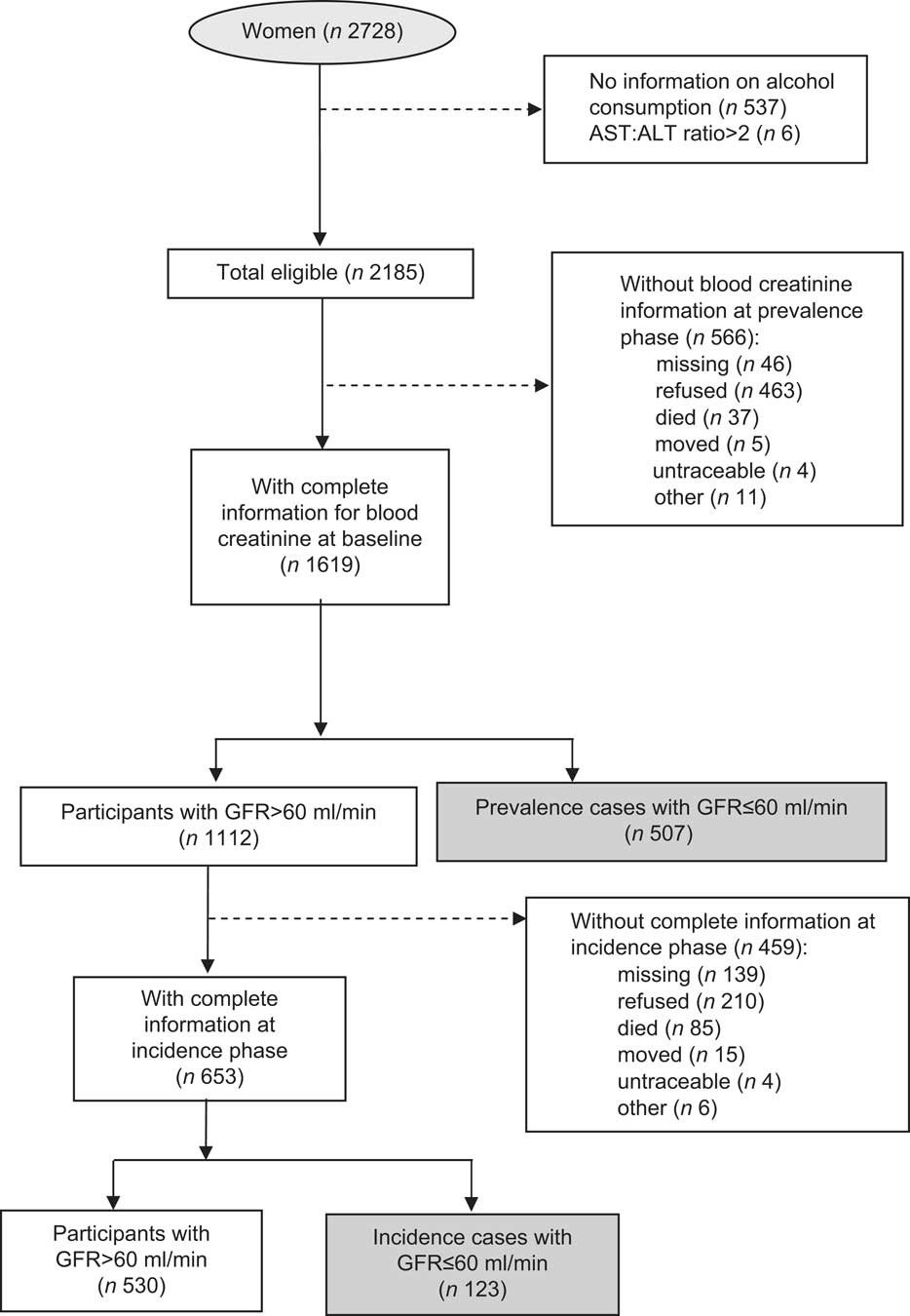

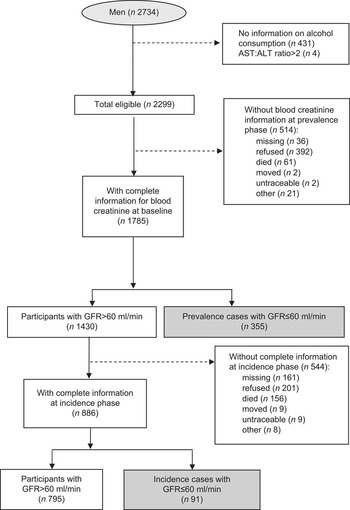

At baseline, 5462 participants (2728 women and 2734 men) were eligible for the ILSA. The present study excluded from the analysis all those lacking baseline information on alcohol consumption (n 968) and those whose ratio of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was higher than 2·0 when they also showed AST > 45 U/l and/or ALT > 55 U/l (n 10), to exclude those suspected to be alcohol abusers. Among the remainder (n 4484), 1080 participants who had no serum creatinine data at baseline were also ruled out. In the end, 3404 participants (1619 women and 1785 men) were analysed at the prevalence phase, while 1539 (653 women and 886 men) whose serum creatinine was assessed at the baseline and at follow-up visits were included in the longitudinal analysis. Details on attrition numbers by gender are given in Figs 1 and 2. A preliminary descriptive analysis (data not shown) showed for both women and men that participants included in the analysis of prevalence data were significantly younger, with lower education, lower prevalence of dementia and higher prevalence of arrhythmia and hypertension than participants who were not included. Among participants included in the analysis, the proportion of abstainers was significantly lower. Differences due to attrition were found also at the incidence phase because the participants included were significantly younger, with lower blood fibrinogen levels and less affected by diabetes and dementia.

Fig. 1 Attrition analysis for women: elderly Italians aged 65–84 years, Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging

Fig. 2 Attrition analysis for men: elderly Italians aged 65–84 years, Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging

Study variables and definitions

Questionnaire

The questionnaire used to collect information included questions on age and education; lifetime hospital admissions; current use of medications (including antihypertensive medications (i.e. diuretics, β-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or calcium antagonists), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cardiac drugs (i.e. diuretics, nitrates, antiarrhythmic drugs and cardiac glycosides)); and food consumption (daily or weekly frequency of consumption of the main categories of foods).

To collect information on drinking habits, the participants were asked: ‘Do/Did you drink wine regularly (nearly every day)?’, ‘Do/Did you drink beer regularly (nearly every day)?’ and ‘Do/Did you drink spirits/appetizers/laced coffee?’ The history of alcohol consumption was assessed by asking people to list the periods of their life with different levels of consumption (questions on amounts based on a standard 125 ml glass for wine and beer, and number of shots for spirits, and on the periods of consumption from age… to age….). Abstainers were identified as those answering ‘no’ to the questions above and reporting that their current and past consumption was null. Drinkers were identified as those answering ‘yes’ to at least one of the above questions, and were classified as former and current drinkers. Former drinkers were those no longer drinking alcoholic beverages at the time of the survey. Current drinkers were considered as those who reported alcohol consumption at the time of the interview, and current consumption was the amount reported at the time of the interview. Alcohol intake was assessed in terms of glasses of wine or beer per day and number of shots of spirit per day, month or year. A trained interviewer converted the amount of each beverage into ml/d using a standard measure of 125 ml per glass of wine and beer, while one shot of spirit corresponded to 40 ml. Total individual alcohol consumption (g/d) was calculated by multiplying the amount of beverage (ml/d) consumed by the amount of alcohol contained in each beverage (g/ml), as recommended by the Italian National Institute of Nutrition(13), and summing each amount. To be precise, we assumed that wine has an alcohol content of 9·4 g/100 ml, beer 3·6 g/100 ml and spirits 28·8 g/100 ml. For the men, the total daily alcohol intake was classified into six alcohol consumption brackets: lifelong abstainers, former drinkers, drinkers of ≤12 g alcohol/d, 13–24 g alcohol/d, 25–47 g alcohol/d and ≥48 g alcohol/d. For the women, the last two categories were pooled (>24 g/alcohol d).

Smoking habit was also considered, i.e. the mean number of cigarettes smoked daily. Those who had never smoked were classified as never smokers and those who smoked >5 cigarettes/d were classified as smokers, either current smokers or former smokers (those who had given up smoking at least 5 years before the baseline investigation).

Blood sampling, blood pressure and anthropometric measurements

Venous blood samples were drawn from each individual after an overnight fast. The blood tests and measurement methods are described elsewhere(Reference Maggi, Zucchetto and Grigoletto12). Briefly, serum creatinine, glycaemia, plasma fibrinogen and serum TAG, LDL cholesterol (LDL-C), HDL cholesterol (HDL-C) and total cholesterol were measured.

Renal function was estimated using the simplified Modification of Diet in Renal Diseases formula, i.e. glomerular filtration rate (GFR)=186×[serum creatinine (mg/dl)]−1·154×(age)−0·203×(0·742 for females)(14). This formula is the preferred method of estimation in elderly people(Reference Fliser15). No adjustment for race was considered because all our patients were white. All GFR values were expressed as ml/min per 1·73 m2 body surface area. A reduced GFR was defined as 60 ml/min or less.

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure values were obtained by averaging the measures taken during the interview, the physical examination and the clinical examination. In data analysis, isolated systolic hypertension was defined as systolic pressure >160 mmHg and diastolic pressure <90 mmHg.

Height and weight were measured with people barefoot and lightly dressed, from which BMI was calculated.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were stratified by gender. To generalize the ILSA sample to the Italian population and to take into account the design effect, a set of weights was defined and applied according to the age distribution of the Italian reference population and the sample fraction. The general characteristics of the participants at baseline were compared by alcohol consumption level. The parametric or non-parametric approach was used, as applicable, for the ANOVA to compare mean values. Distributions of categorical variables (education, smoking habit, diseases) were compared with the χ 2 test. The percentage change in serum creatinine compared with the baseline value was calculated as [(follow-up – baseline value)/baseline value] × 100.

Multiple adjusted least-square means of serum creatinine levels and percentage changes in serum creatinine levels, and the standard error, were calculated using ANOVA within alcohol consumption groups. The adjusting variables were age, BMI, smoking habit, history of hypertension and diabetes at baseline.

The prevalence of low GFR (≤60 ml/min) at baseline was calculated with 95 % CI. Logistic regression analysis was used to estimate OR and 95 % CI for the presence of low GFR, using the alcohol consumption classes as independent variable. Data from the literature suggest there are many factors, potential confounders or intermediates, of alcohol consumption on renal impairment. Age, education, smoking, protein intake and antihypertensive and lipid-lowering drugs were considered confounders, because these factors are involved in renal impairment and in our data are associated with alcohol consumption. As for protein intake, we used BMI as a surrogate of protein metabolic charge. Meanwhile, as alcohol consumption is thought to act potentially on blood cholesterol and fibrinogen, systolic hypertension and diabetes, all of these variables were qconsidered intermediate factors of alcohol action. Based on this, we performed three logistic regression models to assess confounding and to investigate mediation. The first logistic regression model was unadjusted (model 1); model 2 produced OR adjusting for potential confounding variables; and model 3 included potential confounders also adjusting for potential intermediates of alcohol action.

The linear trend of the OR was assessed by treating alcohol consumption as a ranked variable in the logistic models. A quadratic term for alcohol consumption was entered in the models to evaluate if the association was U-shaped. Analysis of trend was performed excluding former drinkers.

The analysis of incident worsening in renal function included only those participants with GFR > 60 ml/min at baseline. The cumulative incidence of low GFR at the follow-up in 1995 was calculated with the related 95 % CI. We compared the risk of low GFR in different alcohol consumption groups, taking abstainers as the reference. To adjust for confounders and intermediates, the three logistic models previously applied were used to estimate adjusted OR for incidence data. Corrected risk ratios (RR) were approximated from OR(Reference Zhang and Yu16).

To explore the effect of plausible competing risks on the relationships between alcohol consumption and renal function, as suggested by the preliminary analysis on participants who were excluded, a sensitivity analysis was performed by applying the previously described models only on participants free from main chronic disease at baseline (heart failure, myocardial infarction, hypertension, stroke, diabetes).

In all analyses, the threshold for significance was set at two-tailed 0·05. Statistical analyses were performed with the SAS statistical software package version 9·1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

In our sample of 1619 elderly women, 477 were lifelong abstainers, 358 former drinkers and 784 were current drinkers. The female drinkers had a mean (sd) alcohol consumption of 16·0 (1·0) g/d, median 11·7 g/d (first quartile = 11·7 g/d, third quartile = 15·4 g/d). Their mean (sd) daily alcohol intake from wine, beer and spirits was 14·5 (8·9) g/d, 0·3 (1·4) g/d and 1·4 (8·5) g/d, respectively.

Among our 1785 elderly men, 138 were lifelong abstainers, 315 former drinkers and 1332 were current drinkers. Among the male drinkers, the mean (sd) alcohol consumption was 31·0 (26·4) g/d, median 23·3 g/d (first quartile = 11·0 g/d, third quartile = 37·8 g/d). Their mean (sd) daily alcohol intake from wine, beer and spirits was 26·6 (22·6) g/d, 0·5 (2·3) g/d and 3·9 (9·7) g/d, respectively. Almost all of these Italian drinkers drank wine (98 % of the men and 99 % of the women).

More detailed results on alcohol consumption in the ILSA can be found in the report by Scafato et al.(Reference Scafato, Gandin and Ghirini17).

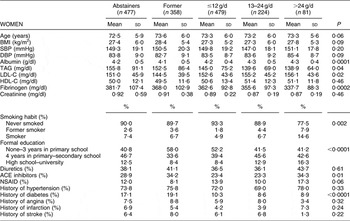

Tables 1 and 2 compare the characteristics of the sample population by drinking category. Among the women, blood fibrinogen (P = 0·0002) and the prevalence of diabetes (P < 0·0001) were significantly and inversely associated with alcohol intake, while smoking habit (P = 0·0002) and serum albumin (P = 0·0001) were directly and significantly associated with alcohol consumption (Table 1). Among the men, formal education, blood fibrinogen and serum creatinine were significantly and inversely associated with alcohol intake at baseline (P < 0·0001, P = 0·005 and P = 0·005, respectively), while smoking habit (P = 0·003), HDL-C (P = 0·005), LDL-C (P = 0·001) and systolic blood pressure (P = 0·0008) were directly and significantly associated with alcohol consumption (Table 2).

Table 1 Women's characteristics at baseline by alcohol consumption (weighted data), Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging

SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Table 2 Men's characteristics at baseline by alcohol consumption (weighted data), Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging

SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

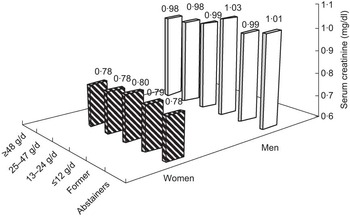

Figure 3 shows the adjusted mean serum creatinine levels at baseline by gender and alcohol intake level. The analysis considered only the 1539 subjects for whom sufficient information was obtained in the incidence phase. The difference between alcohol intake groups was statistically significant only for the men (P = 0·02), with lower mean serum creatinine levels among higher drinking categories.

Fig. 3 Adjusted mean serum creatinine levels at baseline by gender and alcohol consumption: elderly Italians aged 65–84 years, Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging. The analysis considered 653 women and 886 men included in the incidence phase of the study. Mean values were adjusted for BMI, age, smoking, education, hypertension and diabetes at baseline (weighted data). Significance of the difference in serum creatinine by alcohol consumption group: P = 0·33 (women) and P = 0·02 (men)

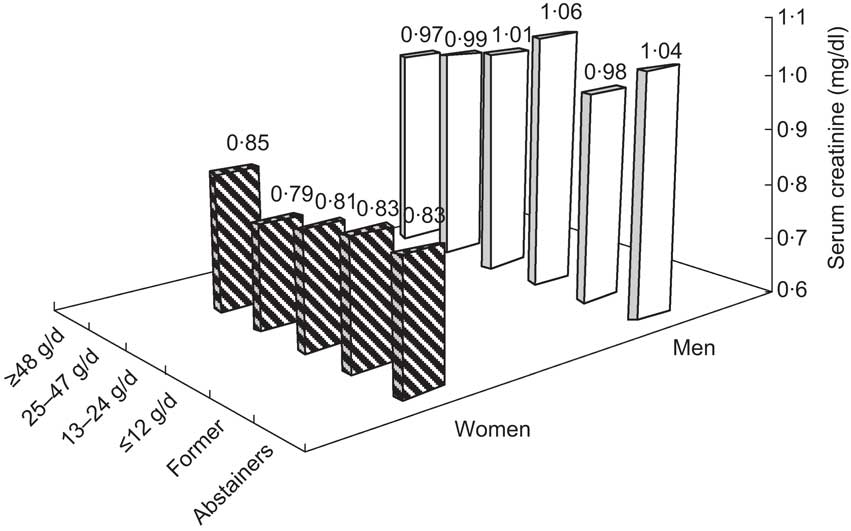

Figure 4 shows the adjusted mean serum creatinine levels at follow-up by gender and alcohol intake level. The difference between alcohol intake groups was again statistically significant only for the men (P = 0·04), lower mean serum creatinine levels coinciding with the heavier drinkers.

Fig. 4 Adjusted mean serum creatinine levels at the 3·5-year follow-up by gender and alcohol consumption: elderly Italians 65–84 years, Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging. The analysis considered 653 women and 886 men included in the incidence phase of the study. Mean values were adjusted for BMI, age, smoking, education, hypertension and diabetes at baseline (weighted data). Significance of the difference in serum creatinine by alcohol consumption group: P = 0·12 (women) and P = 0·04 (men)

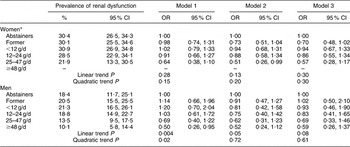

Table 3 shows the prevalence of reduced renal function (GFR ≤ 60 ml/min) at baseline and the results of the adjusted logistic regression models evaluating the association between low GFR and different alcohol consumption groups by comparison with abstainers. Despite the figures, alcohol consumption did not seem to correlate significantly with the prevalence of low GFR in the elderly women and no linear or quadratic terms were statistically significant in any logistic model. For the elderly men, a significant decreasing linear trend (P = 0·05) was shown in the risk of low GFR at baseline with alcohol categories in model 2, and after adjusting for both confounders and intermediates in model 3 the significance was marginal (P = 0·08).

Table 3 Prevalence of renal dysfunction (defined as GFR ≤ 60 ml/min) by alcohol consumption category and OR ratios and 95% CI (estimated with weighted data) obtained from logistic regression models. Abstainers are the reference group

GFR, glomerular filtration rate.

Model 1, unadjusted OR; model 2, OR adjusted for covariates (age, BMI, smoking habit (>20 cigarettes/d), education, antihypertensive and lipid-lowering drugs) at baseline; model 3, OR adjusted for covariates (age, BMI, smoking habit (>20 cigarettes/d), education, antihypertensive and lipid-lowering drugs) and intermediates (isolated systolic hypertension, diabetes, blood fibrinogen and total cholesterol) at baseline.

*For women, the highest drinker category is >24 g/d.

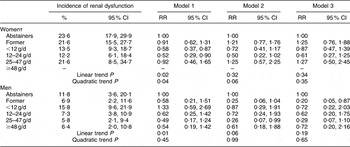

Table 4 gives the adjusted RR for low GFR by comparison with abstainers in the incidence phase by alcohol consumption level. For women the risk of low GFR was not statistically associated with alcohol consumption level. The linear trend was never statistically significant, but in model 2 the quadratic term was marginally significant (P = 0·06). In men, adjusted RR for drinking categories were all lower than 1, even though statistical significance was reached only for former drinkers (RR = 0·18, 95 % CI 0·04, 0·85). The linearity of trend showed marginal significance only in model 2 (P = 0·06).

Table 4 Incidence of renal dysfunction (defined as GFR ≤ 60 ml/min) by alcohol consumption category and RRFootnote * and 95 % CI (estimated with weighted data) performed by different models. Abstainers are the reference group

GFR, glomerular filtration rate; RR, risk ratio.

Model 1, unadjusted OR; model 2, OR adjusted for covariates (age, BMI, smoking habit (>20 cigarettes/d), education, antihypertensive and lipid-lowering drugs) at baseline; model 3, OR adjusted for covariates (age, BMI, smoking habit (>20 cigarettes/d), education, antihypertensive and lipid-lowering drugs) and intermediates (isolated systolic hypertension, diabetes, blood fibrinogen and total cholesterol) at baseline.

* Risk ratios were approximated from the adjusted odds ratios obtained using multivariable logistic regression models.

† For women, the highest drinker category is >24 g/d.

The additional results provided by the sensitivity analyses only including participants free from chronic diseases at baseline (data not shown) supported the linearity of relationships between alcohol consumption and prevalent renal dysfunction in both genders (model 3: P for linear trend = 0·006 and 0·07 for women and men, respectively), while a U-shaped relationship with incidence of renal impairment was confirmed only in women (model 3: P for quadratic term = 0·05).

Discussion

The present study investigated the relationship between moderate alcohol consumption and age-related loss of renal function. Only in men did both prevalence and incidence results seem to suggest an inverse linear relationship between moderate alcohol consumption and the risk of age-related loss of renal function. The results suggest that alcohol might not exert a harmful effect on kidney function in elderly men. In contrast a U-shaped association was shown for women at the incidence phase, suggesting a higher risk of developing renal impairment in elderly women who drink more than 24 g alcohol/d.

The kidneys of elderly people show morphological and haemodynamic alterations that determine a progressive age-associated decline in renal function. On the other hand, several studies have shown that the age-related loss of kidney function is more pronounced in older patients in whom cardiovascular and other risk factors coexist, suggesting a strong relationship between worsening kidney function and hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia and smoking, as well as non-traditional cardiovascular risk factors including inflammation and endothelial dysfunction(Reference Sarnak and Levey3, Reference Elsayed, Tighiouart and Griffith18). The latter factors are also involved in kidney atherosclerotic development, responsible for a so-called ischaemic nephropathy, which is associated with progressive renal fibrosis and therefore with worsening renal function. Actually, the present study confirmed the prognostic role on worsening of renal function of factors such as use of diuretics, smoking and high fibrinogen levels (data not shown), as suggested previously(Reference Baggio, Budakovic and Perissinotto19).

The mechanisms which link alcohol consumption to kidney function can draw on the mechanisms advanced to explain the effects of alcohol consumption on cardiovascular diseases and risk factors(Reference Baggio, Budakovic and Perissinotto19). Recent experimental and human observations indicate that some other components of alcoholic beverages might have beneficial effects on kidney function by influencing oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction and apoptotic mechanisms which play a role in many diseases, including atherosclerosis and several nephropathies(Reference Lo Presti, Carollo and Caimi20). In addition, it was shown that alcohol consumption increases paraoxonase activity(Reference van der Gaag, van Tol and Scheek21) and the latter potently inhibits lipoprotein oxidation(Reference Watson, Berliner and Hama22). It has also been shown that alcohol consumption is associated with healthier blood levels of HDL-C and apo A1. Shaeffner et al.(Reference Schaeffner, Kurth and Curhan23) found that men with HDL-C levels <40 mg/dl had a twofold risk of renal insufficiency after adjusting for other risk factors. Actually our sample population mainly consumes wine (more than 85 % of total alcohol intake) and this does not allow us to analyse alcohol separately from other components. As a consequence, our results cannot be enlarged to drinking habits based on different alcoholic beverages. Nevertheless, our results corroborate findings in the literature.

Referring to inflammatory markers and renal impairment, it has recently been suggested that chronic hypoxia and inflammation are common mechanisms of progressive renal fibrosis, which is associated with worsening renal function. A leading role in this process is played by plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, which facilitates extracellular matrix accumulation by inhibiting plasmin-dependent extracellular matrix degradation. In their epidemiological study, Mukamal et al. found that adults with moderate alcohol consumption had lower plasminogen activator inhibitor antigen-1 levels than non-drinkers(Reference Mukamal, Jadhav and D'Agostino24). There are numerous reports of alcohol consumption in adults and older people being associated with lower blood fibrinogen levels(Reference Perissinotto, Buja and Maggi1) and fibrinogen is a component strongly associated with the progressive deterioration of renal function(Reference Beulens, Stolk and van der Schouw25).

Another far from negligible effect of alcohol has to do with its influence on insulin sensitivity and the incidence of diabetes. Alcohol consumption is associated with type 2 diabetes in a U-shaped fashion, indicating a lower risk of type 2 diabetes in moderate alcohol consumers than in abstainers or heavy drinkers, and this applies to older women too(Reference Buja, Scafato and Sergi26).

On the other hand, alcohol consumption has a harmful effect on systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels, which are risk factors for renal function, as amply demonstrated(Reference Xin, He and Frontini27). Our results nevertheless suggest that the overall direction of association of alcohol leans towards a non-detrimental effect on renal function in elderly men.

Furthermore, in our analysis the adjusted results obtained from the model including known intermediate factors were very similar to those obtained from the model adjusting only for confounders. These results seem to suggest that other mechanisms should be involved in the likely association between alcohol and renal function.

The association of alcohol consumption on renal impairment appeared to differ in women and men. Among women alcohol consumption was related to renal impairment with a U-shaped dose effect, while in men a decreasing linear trend for the risk of renal dysfunction among drinking categories was shown. Actually, our results are in agreement with previous evidence on sex-specific susceptibility to alcohol effects. Men and women differ in their ability to metabolize alcohol, possibly due to gender-related differences in total fluid distribution volume, lean body mass, or activity of the enzymes processing alcohol in the liver(Reference Kwo, Ramchandani and O'Connor28). Sex steroids may have a role in cytochrome enzyme expression and in regulating hepatic oxidant stress status(Reference Wolbold, Klein and Burk29). The overall result is a higher susceptibility of women to alcohol action, exposing women to harmful effects also for low doses.

The present study suffers from a number of limitations. First, information about alcohol consumption was self-reported; however, alcohol consumption is very common in Italy (particularly among older people) and so reporting on drinking habits is unlikely to cause embarrassment. Second, no information was obtained on drinking patterns; participants were not asked about the proportions of alcohol they drank with meals or at other times. Third, as wine was by far the most common alcoholic beverage used by our sample, we cannot distinguish between the specific contribution to our findings of alcohol per se and of other components of the alcoholic beverages. Fourth, the FFQ was not validated and it did not allow us to evaluate daily nutrient intake. Fifth, even though the study was population-based and the sample size was remarkable, attrition heavily reduced the sample size of critical groups, in particular women drinking more than 24 g alcohol/d and male abstainers. This caused inadequate power in the statistical analyses and consequently, although the results suggested well-defined trends, statistical significance of the difference was only roughly achieved. Moreover, our results could be affected by risks due to those diseases that could compete with alcohol consumption on health outcomes. In fact, those who drink large amounts of alcohol may die from other causes such as heart failure, diabetes or myocardial infarction. Nevertheless the sensitivity analysis performed only on participants free from chronic diseases at prevalence phase confirmed the results. Finally, as this was an observational study, a causal interpretation of the relationship between the exposure and the outcome is not allowed.

Conclusions

Our results suggest a not harmful association of moderate alcohol consumption on the risk of renal impairment in elderly men. In accordance with the recommendations on alcohol consumption in the elderly and subject to individual characteristics, moderate quantities of alcohol may not have an injurious association on renal function in the elderly and perhaps even a beneficial association for men and for women at very light consumption (less than 24 g/d) only. The mechanisms of alcohol on the cardiovascular system might also be invoked to explain the results on renal function. Nevertheless, in translating the results of the research into general policy on alcohol consumption we cannot forget the proved harmful causal relationship between alcohol and mortality for a high number of diseases directly or indirectly deriving from any consumption, and the adverse effects of alcohol on risk of falling and interactions with medication. Furthermore, special warning is necessary for drinking among women because of their major vulnerability to alcohol effects that, even at light intake, would significantly raise their risk of developing diseases.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: The Italian National Research Council supported the ILSA project from 1991 to 1998 as part of the Progetto Finalizzato Invecchiamento and in 1999 as part of the ‘Biology of Aging’ Strategic Project. Since 1999 ILSA has been coordinated by the National Centre for Epidemiology, Surveillance and Health Promotion – CNESPS Population Health Unit at the Istituto Superiore di Sanità and funded by the Ministero della Sanità through the programme ‘Epidemiology of the Elderly’ and the ‘Estimates of Health Needs of the Elderly’ special programme of the Tuscany Region. Conflicts of interest: None. Author contributions: guarantors for the integrity of the study: E.M. and E.S.; study conception and design: A. Buja, E.P., G.S. and S.M.; intellectual content: E.P., A. Buja, G.R. and S.G.; statistical analysis: E.P. and A. Buja; data interpretation: A. Buja, S.M., E.S., B.B. and A. Basile; manuscript writing: E.P., A. Buja and G.S. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Acknowledgements: The ILSA Working Group comprises the following individuals. E. Scafato (MD), G. Farchi (MSc), L. Galluzzo (MA) and C. Gandin (MD), Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Roma; A. Di Carlo (MD) and M. Baldereschi (MD), CNR, Firenze; G. Crepaldi (MD), S. Maggi (MD), N. Minicucci (PhD) and M. Noale (PhD), CNR, Aging Section, Padova; A. Capurso (MD), F. Panza (MD, PhD), V. Solfrizzi (MD, PhD), V. Lepore (MD) and P. Livrea (MD), University of Bari; L. Motta (MD), G. Carnazzo (MD), M. Motta (MD) and P. Bentivegna (MD), University of Catania; S. Bonaiuto (MD), G. Cruciani (MD) and D. Postacchini (MD), Italian National Research Center on Aging, Fermo; D. Inzitari (MD) and L. Amaducci (MD), University of Firenze; C. Gandolfo (MD) and M. Conti (MD), University of Genova; N. Canal (MD) and M. Franceschi (MD), San Raffaele Institute, Milano; G. Scarlato (MD), L. Candelise (MD) and E. Scapini (MD), University of Milano; F. Rengo (MD), P. Abete (MD) and F. Cacciatore (MD), University of Napoli; G. Enzi (MD), L. Battistin (MD), G. Sergi (MD), F. Grigoletto (ScD) and E. Perissinotto (ScD), University of Padova; P. Carbonin (MD), Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Roma.