The European Union (EU) project ‘Protection, Promotion and Support of Breastfeeding in Europe: A Blueprint for Action’(1) produced, among other documents, a report on the breast-feeding situation in twenty-nine EU and associated countries in 2002(2, Reference Cattaneo, Yngve and Koletzko3). The follow-on EU project ‘Promotion of Breastfeeding in Europe: Pilot Testing the Blueprint for Action’(4), carried out in eight countries (BE, DK, FR, IE, IT, LU, LV, PLFootnote †) between 1 May 2005 and 30 April 2008, used the same questionnaire to reassess the breast-feeding situation in 2007. In September 2007 the questionnaire was sent to the thirty countries surveyed in 2003 and completed questionnaires were returned to the project coordinator between the end of 2007 and the beginning of 2008. These two sets of data represent a unique opportunity to assess progress since 2002 and to compare the achievements of the eight countries participating in the follow-on project with those of other EU and associated countries.

Methods

In the first quarter of 2003, a questionnaire, available as supplemental web material, was sent to relevant key informants in the then fifteen member states of the EU, as well as to CH, IC and NO. Through the WHO European Office, the questionnaire was also sent to BG, CY, CZ, EE, HU, LT, LV, MT, PL, RO, SI and SK, as these were EU accession and candidate countries at that time. In 2007 the same questionnaire was sent to key informants in the same countries. As far as possible, the 2003 and the 2007 questionnaires were completed by the same people in the participant countries. If this was not possible due to staff turnover, the 2003 key informants were asked to provide contact details for their replacement.

In 2003, of thirty countries approached, completed questionnaires were received from twenty-nine (all except CY); in 2008, twenty-four countries returned the requested information (BG, CH, CY, EE, HU and MT did not). The number of returned questionnaires was in fact twenty-seven, as UK sent four (one each for England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland), as in 2003. Of the twenty-seven key informants, ten were government officials, fourteen were employees of national health systems and three worked with non-government organizations (NGO). Fourteen of the respondents were either national breast-feeding coordinators or members of national breast-feeding committees. Finally, in each of the ten sections of the questionnaire a blank box was provided for free comments on the subject of that section; some of the information reported in the results is derived from these comments.

Results

Policy, planning and management

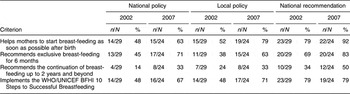

Six out of twenty-four (25 %) countries lacked a national policy in 2007 (AT, CZ, FR, IC, PL, PT), compared with eleven out of twenty-nine (38 %) in 2002 (AT, BE, CH, CZ, FI, HU, IC, IT, PT, RO, SI). Table 1 shows the number of countries with a national and/or local policy and/or national recommendations in 2002 and 2007, incorporating each of four criteria. In 2002, five countries, all among accession or candidate countries (LT, LV, MT, PL, SK), had national policies that met all four criteria. In 2007, four more countries, all participants in the pilot project (BE, IE, IT, LU), had succeeded in developing policies incorporating all four criteria. LT and SK reaffirmed their policy commitments to apply all four criteria; LV in the interim had dropped the criterion of ‘helping mothers to start breast-feeding as soon as possible after birth’. In the intervening period PL had abandoned its national policy due to changing political commitments. However, the Lublin region of PL (which was a participant of the Blueprint pilot project) had developed its own local policy, which includes all four criteria. After the collection of the 2007 data, AT adopted a national policy that meets all four criteria, using the model proposed by the revised Blueprint for Action(4).

Table 1 Countries with policies and recommendations meeting stated criteria in 2002 and 2007

BFHI, Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative.

In 2002, ten out of twenty-nine countries (BG, DE, DK, EE, EL, ES, NL, NO, SE, Scotland) reported policies covering three out of four criteria; in 2007 three more countries (FI, RO, SI) reported achieving this level of policy commitment, while two countries (ES, Scotland) had policies covering fewer criteria than in 2002. The majority of countries limited the recommended optimal duration of breast-feeding to 1 year of age or beyond instead of adopting the WHO recommendation of 2 years or beyond. This latter was the most common criterion not adopted in both the 2002 and 2007 surveys. The number of countries where exclusive breast-feeding was recommended up to 6 months increased between 2002 and 2007. Nearly half of the countries stated in 2007 that they performed public monitoring of adherence to, or implementation of, policies and recommendations (EL, FI, IE, LT, LU, LV, PL, SI, SK, England, Wales, Scotland), up from five out of twenty-nine countries in 2002.

Finally, seven countries developed or revised their national plans of action during this period, bringing the total number up to sixteen out of twenty-four, compared with thirteen out of twenty-nine in 2002. In 2007, only AT, SE and SK had no national action plan and were not envisaging drafting one. Except for PL, where a local action plan was developed for the Lublin area (as part of the Blueprint pilot project), all eight countries of the pilot project had a national plan. The proportion of countries with a national breast-feeding committee had gone up from 69 % in 2002 to 79 % in 2007, but no such improvement was reported in the proportion of countries with a national breast-feeding coordinator. Little improvement was also reported in terms of financial support for initiatives recommended by national committees and coordinators. The additional actions urged in the 2005 Innocenti Declaration(5) did not appear to have accelerated the process of change. In 2007, ES, FR, IC and IT were the only countries lacking both a national coordinator and a national committee. Among the countries in the pilot project, DK, IE, LU and LV had both a coordinator and a committee regularly funded, but the government of DK has decided to withdraw its funding for these by the end of 2008. PL had an unfunded committee and no coordinator. In 2007, only four countries (NL, PL, PT, SE) had no funds available for initiatives proposed by their committees and there were still eight national committees relying on irregular funding sources (CZ, DE, EL, FI, LT, SI, SK, Scotland).

Training

Pre-service training provision was reported as inadequate both in 2002 and in 2007. About 25 % of countries (eight of twenty-nine in 2002 and six of twenty-four in 2007) reported the existence of national boards that certify some level of pre-service breast-feeding training, but standards for these were frequently reported as inadequate. Where curricula for pre-service training existed, these mainly related to the training of midwives and nurses in health-care training colleges (at either undergraduate or postgraduate level). With reference to in-service training, the number of countries using the quality-assessed 18 h UNICEF/WHO course on breast-feeding practices and/or the 40 h WHO/UNICEF course on counselling for health professionals did not change between 2002 and 2007. Six countries (DK, FR, IC, NL, NO, SE) had not introduced either of these courses; some of them, however, had introduced some other form of in-service course (DK, NO, SE). Besides the translation difficulties, a further potential reason given for not using the 18 h and 40 h courses was that they are considered too basic by some service providers. Most of the alternative courses incorporated core aspects of the WHO and UNICEF courses and their duration varied from a few hours to 200 h. Some of these courses (in DE, for example) were officially endorsed and led to a recognised certificate and/or academic credits. However, there was little assessment of the quality and effectiveness of these courses, except in DK. The coverage of in-service training using quality-assessed UNICEF and WHO courses was increasing. Specifically, the number of countries with high or medium coverage with the 18 h course doubled from seven of twenty-nine (24 %) in 2002 to twelve of twenty-four (50 %) in 2007. A similar increase was reported in the number of countries with high or medium coverage with the 40 h course (three of twenty-nine (10 %) in 2002 to five of twenty-four (21 %) in 2007). In-service training coverage was higher for nurses and midwives than for doctors; among the latter, paediatricians were more likely to undergo training than obstetricians. The number of International Board Certified Lactation Consultants (IBCLC) was also increasing in most countries. Six countries were still without an IBCLC (BG, CZ, LV, MT, RO, SK). PT had one, DE over a thousand, several countries more than a hundred (NL 360, AT 317, UK 268, FR 238, IT 168, IE 136, BE 120, PL 108). The ratio of the number of IBCLC to the whole population was highest in IC (about 1:14 000), followed by AT (1:26 000), IE (1:31 000), NL (1:45 000) and SI (1:48 000).

Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative

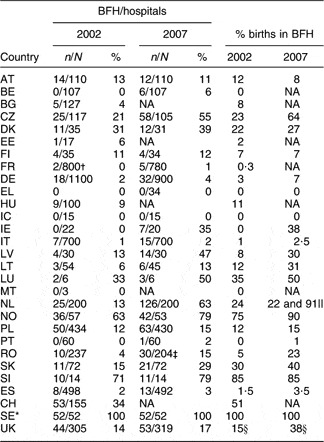

The Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) was certainly the field in which most improvements were achieved between 2002 and 2007. EL and IC have no designated Baby Friendly Hospitals (BFH); in SE, all hospitals are BFH, but no reassessment has been done at national level since 2003. All countries with the BFHI, except for FI and SE, had a BFHI coordinator in 2007, compared with twenty-two out of twenty-seven in 2002. In that year, twelve out of twenty-nine (41 %) countries had no designated teaching BFH: BE, EE, EL, FI, FR, IC, IE, IT, LT, LV, MT and PT. In 2007, seven out of twenty-four (29 %) countries fell into this category: EL, FR, IC, IT, LT, LV and PT. The number of teaching BFH, however, continued to remain low. Except for AT and FI, the number of BFH and the percentage of infants born in BFH increased in all countries. Table 2 shows the number of BFH out of all hospitals by country, as well as the percentage of births taking place in BFH in 2002 and 2007. The data from NL include home-care organisations providing maternity care in the mother’s own home. In DK, some BFH merged, and this has impacted on the relatively modest increase in the number of BFH. The number of countries where more than 50 % of infants are born in BFH went up from four in 2002 (CH, NO, SE, SI) to six (the same four plus CZ and NL) in 2007. Six countries in 2002 (CZ, DK, LU, NL, SK, UK) and nine in 2007 (DK, IE, LT, LU, LV, PL, RO, SK, UK) had percentage births in BFH in the intermediate range (15–50 %), while nineteen in 2002 and ten in 2007 had lower percentages (0–15 %). The Global Criteria for the achievement of a BFH award were not fully applied in all countries, but the number of countries where they were applied was increasing. Some countries with very low rates of breast-feeding initiation (FR, IE, UK) used a nationally designated BFH award which did not require the achievement of rates of exclusive breast-feeding at discharge of 75 % or higher. In NO, some BFHI steps (Steps 4, 6, 7, 9) had been strengthened and an eleventh step was added, which involves optimal care for the mother to enable her care better for her baby. The BFHI requires the reassessment of BFH every 2 to 5 years, most commonly this was done every 3 years. In some countries the first reassessment was programmed to take place 1–2 years after designation and thereafter less often. Ceasing the acceptance of free formula donations by hospitals was a challenge to the expansion of the BFHI in some countries, as was the fact that the BFHI is generally under-funded.

Table 2 Number and percentage of Baby Friendly Hospitals (BFH) by country and percentage of births in BFH in 2002 and 2007

NA, not available.

*No reassessment since 2003.

†Self-assessed using global Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative criteria.

‡These thirty hospitals are active as BFH but have not been officially certified yet.

§Up from 8 % to 11 % (England), 34 % to 46 % (Wales), 38 % to 56 % (Scotland) and 20 % to 39 % (Northern Ireland), between 2002 and 2007.

||For hospitals and maternity homes, respectively.

Applying the Baby Friendly Initiative, based on the adaptation of the 10 Steps, to primary health-care settings was increasing and up from 38 % in 2002 to 50 % of countries in 2007. These initiatives were either being planned or implemented in BG, CZ, DE, DK, FI, HU, IT, LT, NL, NO, SE, SI, SK and UK. Many countries were extending the initiative to other health, academic and employment areas such as general paediatric service areas, neonatal intensive-care units, health professional colleges and health service workplaces.

International Code and subsequent relevant Wold Health Assembly resolutions

In the period between 2002 and 2007 no further legislative initiatives were reported in relation to controlling the marketing of breast-milk substitutes and allied products within the scope of the WHO Code. This was not surprising, as such changes usually occur over longer periods of time and are often dependent on the ratification of international conventions and resolutions and on the issue of European Commission (EC) directives. All EU member states voted in favour of the Code in 1981; they followed a similar course of action also for subsequent relevant World Health Assembly (WHA) resolutions. In 1991, the EC adopted some provisions of the Code in its directive for the internal marketing of infant and follow-on formulae (91/321/EC). In December 2006 the EC issued an updated directive (141/06/EC); this did not make a substantial change towards the application of all the provisions of the Code, while subsequent WHA resolutions were not even taken into account. The main differences between the EC directives and the Code can be summarised as follows. The EC directives:

1. Only apply to infant and follow-on formulae; marketing restrictions, however, only apply to the former.

2. Do not apply to other breast-milk substitutes, including complementary foods that can be used as a replacement for breast milk.

3. Do not apply to feeding bottles and teats, which are covered by the Code.

4. Do not define ‘health care system’, ‘institutions and organisations’ and ‘publications specialised in baby care’; this can lead to ambiguity in interpretation with regard to donations of infant formula, the provisions of low-cost supplies, and where advertising is permitted.

EU member states have for the most part adopted the EC directives. Whenever monitoring of compliance with the Code has been conducted (in IE, IT, LU and LV during the period covered by the current article), violations have been discovered. There was a general lack of awareness of the Code among the public and health professionals. Limited official dissemination of information about the Code and its implementation had taken place in few countries.

Legislation for working mothers

No changes since 2002 were reported for the legislation on maternity protection, except from IE, where the entitlement period for maternity leave was increased from 18 to 26 weeks paid and 16 additional weeks unpaid, and UK, where statutory maternity leave was extended to 52 weeks in 2007. In most countries, the legislation on maternity protection with relevance to breast-feeding goes beyond the minimum standards recommended by the International Labour Organization (ILO) 183 Convention, even though only nine EU countries ratified it: AT, BG, CY, HU, IT, LT, LU, RO and SK. The ILO standards had been fully implemented in about two-thirds of countries (eighteen of twenty-nine in 2002 and fifteen of twenty-four in 2007) and partially implemented in the remaining ones. Where national legislation did not meet the ILO standards, it was mainly due to the lack of provisions for lactation breaks or lack of job protection and non-discrimination for breast-feeding workers. The standard regarding paid breast-feeding breaks during working time was not met in DK, FI, FR, IC and UK in 2007. Moreover, ES, FR, IC, PT, SK and UK had no specific legislation for job protection and non-discrimination for breast-feeding workers. Fathers could often share the maternity protection benefits granted to mothers under national legislation. Scandinavian countries had parental leave instead of maternity leave, which allowed parents to share equally the leave or part of it. Moreover, many categories of working mothers (e.g. women employed for less than 6–12 months at the time of application for maternity leave, contract workers, irregular part-time workers and apprentices/working students) were not covered by the legislation in many countries. Finally, most national jurisdictions had not adapted sufficiently to enable mothers achieve the recommendation regarding exclusive breast-feeding for 6 months, adopted as policy by many countries.

Community outreach, including voluntary mother-to-mother support

In 2007, all respondents reported that peer counsellors and/or mother-to-mother support groups and organisations were providing services in their countries; in 2002 there were no such groups in IC and RO. In many cases these groups were involved in the promotion and support of breast-feeding long before any concerted public health initiative/activity on breast-feeding started. The number of these NGO was increasing slowly, as was the coverage of the services they provided, although this was rated as medium in about half of the respondent countries. High coverage of mother-to-mother support services was reported only from Scotland. It was reported that links between these groups and health-care services deteriorated since 2002; links rated as medium to high in 2002 numbered sixteen out of twenty-nine (55 %), whereas in 2007 this number dropped to ten out of twenty-four (42 %). On the other hand, in 2007 more health services were organising/facilitating mother-to-mother support groups (sixteen out of twenty-four (67 %)) than in 2002 (fifteen out of twenty-nine (52 %)). In an increasing number of countries volunteer mother-to-mother support organisation members were receiving some training in breast-feeding management and support. In 2002 around half the countries were offering, either through health services or NGO, training for peer counsellors and one-third of these countries reported its coverage as medium to high, while in 2007 almost three-quarters of the countries were providing training, with medium to high coverage in half of them. Women were made aware of the availability of these groups through newsletters, health service information materials/consultations (during antenatal care or at discharge after delivery), telephone directories and Internet sites. Mothers who needed information or support usually attended mother-to-mother group meetings, or got in touch by phone and increasingly by e-mail and through the Internet. Support was usually provided via the same channels, but sometimes also through home visits, written materials and videos.

Information, education, communication

In an increasing number of countries, governments allocated some funds for breast-feeding promotion and other related communication activities. This number went up from sixteen out of twenty-nine (55 %) in 2002 to seventeen out of twenty-four (71 %) in 2007. These funds were mainly allocated for the production of information/education materials for health professionals and mothers in the form of booklets, leaflets, flyers, posters, stickers, videos, television spots and media campaigns, but funds were also available for projects, BFHI materials, guidelines, training and workshops. Information and education materials were reviewed and revised as necessary. They were widely and regularly disseminated in some countries, irregularly in others. It is difficult, however, to say whether communication was fully in line with WHO and UNICEF recommendations, and to estimate whether it reached those most in need and how effective it was. Except in DE, IC, LU, UK and partially in LV and NO, no provisions were made to audit the impact of these materials/initiatives in terms of both coverage and effectiveness (coverage was audited in DE only). Activities marking the World Breastfeeding Week (WBW) each year increased between 2002 and 2007 and this applied to all countries except IC and RO. Most respondent countries had also designated a National Breastfeeding Week (NBW) and this usually fell in October, apart from PL and UK (where NBW is in May), the Flemish-speaking region of BE, CZ, LT and LU (where NBW is in August) and in EL (where NBW was marked in November). Activities marking WBW and NBW were organised by NGO and UNICEF in nearly half the countries, with state bodies organising them in almost one-third of respondent countries.

Monitoring

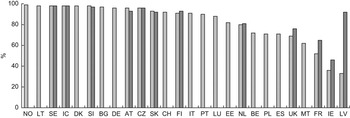

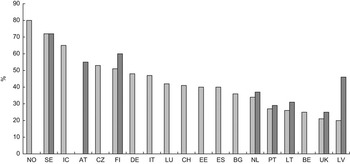

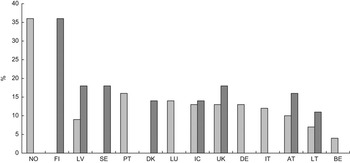

As far as data collection for monitoring breast-feeding rates is concerned, there were no marked differences between 2002 and 2007. Collection of data on breast-feeding rates was almost always funded by governments, within the budgets assigned to health-care systems. Three countries had no national/regional health service data collection systems. These were DK (although a national data collection system was due to start in 2008), NL (where a private research institute funded by the government collected data regularly on a sample base) and PL (due to lack of funding). The lack of standardised definitions, methods, age groups and indicators, across and within countries, prevented comparisons between countries in 2002; this situation had not improved in 2007. Moreover, only half of the respondent countries had data available in 2007 that updated the figures submitted in 2002. Figures 1–4 show the national data that were available. Improvements in the rates of initiation of breast-feeding were reported from FR, IE, LV and UK, the countries in which rates were very low in 2002 and, except in LV, continued to be lower than elsewhere in 2007. Rates of initiation remained as they were or were slightly decreasing in the countries with high rates in 2002 (AT, CZ, FI, IC, SE, SI, SK). From countries that reported comparable data at 3–4 months, all except NL showed an improvement. Higher rates of exclusive breast-feeding at 6 months were reported from LT, LV, NL and SK, while rates were unchanged in FI and were apparently decreasing in AT; however, this latter is an artefact due to a change of definition between surveys. In those countries reporting data for any breast-feeding at 6 months the rate had gone up in FI, LT, LV and UK, and to a lesser extent in NL and PT, while it remained unchanged or decreased in PT and SE. All the countries with two sets of data at 9–12 months reported some improvement.

Fig. 1 Rates of initiation of breast-feeding in Europe: 1998–2002 (![]() ) and 2003–2007 (

) and 2003–2007 (![]() ). Data missing from EL, HU and RO. SI, SE and MT: any breast-feeding at discharge. PL and IE: exclusive breast-feeding at discharge. IC: any breast-feeding at 1 week. ES, EE and LV: any breast-feeding at 6 weeks. FI: any breast-feeding at age less than 1 month. NL and SK: initiation of exclusive breast-feeding. All other countries: initiation of any breast-feeding

). Data missing from EL, HU and RO. SI, SE and MT: any breast-feeding at discharge. PL and IE: exclusive breast-feeding at discharge. IC: any breast-feeding at 1 week. ES, EE and LV: any breast-feeding at 6 weeks. FI: any breast-feeding at age less than 1 month. NL and SK: initiation of exclusive breast-feeding. All other countries: initiation of any breast-feeding

Fig. 2 Rates of any breast-feeding at 6 months in Europe: 1998–2002 (![]() ) and 2003–2007 (

) and 2003–2007 (![]() ). Data missing from DK, EL, FR, HU, IE, MT, PL, RO, SK and SI

). Data missing from DK, EL, FR, HU, IE, MT, PL, RO, SK and SI

Fig. 3 Rates of exclusive breast-feeding at 6 months in Europe: 1998–2002 (![]() ) and 2003–2007 (

) and 2003–2007 (![]() ). Data missing from BE, BG, EE, EL, FR, IE, MT, PT and SI. DK and SE: full breast-feeding. UK and NL (2007): exclusive breast-feeding at 5 months

). Data missing from BE, BG, EE, EL, FR, IE, MT, PT and SI. DK and SE: full breast-feeding. UK and NL (2007): exclusive breast-feeding at 5 months

Fig. 4 Rates of breast-feeding at 12 months in Europe: 1998–2002 (![]() ) and 2003–2007 (

) and 2003–2007 (![]() ). Data missing from BG, CH, CZ, EE, EL, ES, FR, HU, IE, MT, NL, PL, RO, SI and SK. UK: at 9 months

). Data missing from BG, CH, CZ, EE, EL, ES, FR, HU, IE, MT, NL, PL, RO, SI and SK. UK: at 9 months

Disadvantaged groups

In most countries, there was no specific policy or plan addressing the poor uptake of breast-feeding by mothers from disadvantaged groups. Some specific policy and action plans had been developed and/or implemented in relation to these groups in eleven out of twenty-nine countries (38 %) in 2002 and in eleven out of twenty-four (46 %) in 2007. They addressed smokers, teenagers, less educated families, lower socio-economic groups, immigrant women or minority groups. With regard to the latter groups some countries, such as AT, DE and UK, provided translated information leaflets free of charge to members of the main minority groups. In LU the disadvantaged groups were specially mentioned in the new action plan, with preferential access to free individual breast-feeding counselling. In several districts of SK, training programmes for Roma mothers were introduced in cooperation with local health workers. In RO there were networks of community nurses and Roma mediators at county level with a focus on disadvantaged groups. There were also local activities carried out by health authorities and NGO targeted at meeting the needs of these communities. These activities generally focused on reducing inequalities in health and did not specifically address breast-feeding. Where data on breast-feeding rates were gathered, this usually included information on variables associated with health inequalities, such as age, educational attainment, residence and occupation, but less often on family income, employment status and ethnicity.

Discussion

The current situation in the countries surveyed is extremely heterogeneous. However, a number of conclusions can be drawn. The conclusion arrived at in the 2002 survey – that breast-feeding rates and practices in EU countries fall short of WHO and UNICEF recommendations, and of targets and recommendations proposed in national policies and by professional organisations – still holds true. Even in countries where initiation rates are high, there is a marked fall-off in breast-feeding in the first 6 months. The trend in breast-feeding rates is improving slowly, as shown by the modest increases in the rates of initiation, any breast-feeding at 6 months and continued breast-feeding at 12 months in Figs 1, 2 and 4. Except for AT and LV, where definitions and methods changed between surveys, improvements are probably true and not artefactual. Despite these improvements, the rate of exclusive breast-feeding at 6 months throughout Europe is overall lower than recommended. Yet, between 2002 and 2007 there was a marked improvement in the number of BFH, the percentage of births in BFH, and to a lesser extent in the availability and coverage of in-service training and the number of IBCLC. There was also some improvement in policy, planning, management, communication and mother-to-mother support, while no legislative changes were reported at either EU or national level in extending breast-feeding protection to give full effect to the International Code. Some minor improvements in maternity protection legislation have occurred (extension of maternity leave and entitlement to paid workplace breast-feeding breaks) but this has not been very extensive.

The interventions needed to increase the rates of initiation, exclusivity and duration of breast-feeding have been systematically reviewed(Reference Dyson, McCormick and Renfrew6–Reference Spiby, McCormick and Wallace10). Although the evidence base needs to be strengthened(Reference Renfrew, Spiby and D’Souza11), especially as far as the evaluation of the effectiveness of different policies is concerned, there is clear evidence for the effectiveness of many interventions that, if employed, can bring about significant improvements to the current situation. What is required is investment in these interventions; for example, better resourcing for pre-service and in-service training, funding for the extension of the Baby Friendly Initiative to all maternity, child care and community health facilities, enhancement in support for peer counsellors and mother-to-mother support groups. Improvements in the legislative protections for breast-feeding by rigorously applying the International Code and subsequent WHA resolutions, and improving workplace and societal protections, are also essential and require political commitment. Comprehensive, timely, accurate and comparable data sources are urgently required to monitor progress, test effectiveness and compare results within and between countries.

Finally, the eight countries that pilot-tested the Blueprint for Action, and contributed to its revision and validation, performed comparatively better between 2002 and 2007 than the remaining EU respondent countries as far as implementation of breast-feeding interventions is concerned. This is partly due to the fact that participation in the project required the development and/or revision of a breast-feeding plan of action, following a thorough analysis of current breast-feeding rates and practices. Compared with the other countries, these eight countries achieved better results in:

1. The development of policies and recommendations, aided significantly by the availability of a template document developed in a parallel project(12).

2. The appointment of breast-feeding committees and coordinators.

3. The implementation of in-service training.

4. The rate of designation of new BFH.

5. The monitoring of compliance with the International Code.

It was not possible, however, to link these achievements directly with any improvements in their rates of breast-feeding. It is the opinion of the research team that unless breast-feeding services improve (using best-evidence-based models), legislative protections are enhanced and pre-service and in-service training is upgraded and made more widely available (particularly in the large teaching hospitals), it is unlikely that any marked improvements in breast-feeding rates will be achieved anywhere in Europe for the foreseeable future.

Acknowledgements

The project of which the current paper is a part was carried out with financial support from the European Commission, Health and Consumer Protection Directorate-General, Directorate G – Public Health, EU Project Contract No. SPC 2004326 ‘Promotion of Breastfeeding in Europe: Pilot Testing the Blueprint for Action’. The study does not necessarily reflect the Commission’s views and in no way anticipates the Commission’s future policy in this area. All the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. A.C. and T.B. wrote the first draft of the paper, based on the project report submitted to the European Commission. All the remaining authors, in addition to providing data from their own countries, revised the draft and read, commented on and approved the final manuscript. The following people, in addition to the authors, provided the requested information: Ilse Bichler, Anne-Marie Kern, Renate Fally-Kausek, Martina Esberger and Margaritha Kindl (AT); Françoise Moyersoen (BE); Anna Mydlilova, Magdalena Paulová and Dagmar Schneidrová (CZ); Mathilde Kersting, Anke Weissenborn, Michael Abou-Dakn, Denise Both, Kristiana Heindel, Gabriele Kewitz, Gudrun von der Ohe and Tarané Probst (DE); Tine Jerris (DK); Vicky Benetou and Themis Zachou (EL); Luis Ruiz Guzman (ES); Sirpa Sarlio-Lähteenkorva and Marjaana Pelkonen (FI); Flore Marquis and Annick Vilain (FR); Geir Gunnlaugsson, Sesselja Gudmundsdottir and Jona Margret Jonsdottir (IC); Genevieve Becker (IE); Leonardo Speri (IT); Roma Bartkeviciute, Giedra Leviniene, Daiva Sniukaite, Egle Markuniene and Ausrute Armonaviciene (LT); Yolande Wagener (LU); Dace Zavadska, Dina Kruze, Jevgenija Livdane, Ilze Kreicberga, Klaudija Hela, Vineta Vēja, Skaidrite Vasaraudze, Sarma Sleze, Aiga Rurane and Iveta Pudule (LV); Adrienne de Reede and Heleen Hayes (NL); Anne Bergljot Bærug (NO); Isabel Loureiro (PT); Petronela Stoian and Alin Stanescu (RO); Ulla-Kaisa Koivisto Hursti, Kerstin Nordstrand, Elin Siljehag, Ylva Arnhof, Gunnar Johansson, Vilhelm Nordenanckar, Mattias Grundström, Camilla Lööw-Lundin and Kristina Sjölin (SE); Borut Bratanič (SI); Viera Hal’amová, Pavol Šimurka, František Bauer, Helena Drobná and Katarína Vicianová (SK); Sheela Reddy, Janet Calvert, Linda Wolfson, Jane Britten and Susan Sky (UK).