The Mediterranean diet is characterized by the use of certain food items with known beneficial effects on health. The relationship between adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern and reduced mortality or lower incidence of major chronic diseases has been widely studied across multiple epidemiological analytical studies(Reference Fung, Rexrode and Mantzoros1–Reference Trichopoulou, Bamia and Trichopoulos6). A key feature of the Mediterranean dietary pattern is the consumption of an adequate breakfast, which can be defined as the first meal of the day, taken before or at the start of daily activities with an energy content that meets 20–25 % of total daily energy needs(Reference Aranceta, Serra-Majem and Ribas7–Reference Giovannini, Verduci and Scaglioni9), and which includes dairy products, cereals, fruit and healthy fats. Among both adults and adolescents, the skipping of breakfast has been associated with smoking, infrequent exercise, low educational level, frequent alcohol use and high BMI(Reference Keski-Rahkonen, Kaprio and Rissanen10–Reference Christoforidis, Batzios and Sidiropoulos13). It has been reported that the failure to consume an adequate breakfast contributes to poor school performance and to dietary deficits that are rarely compensated for at other meals and may lead to a higher consumption of energy-dense snacks later in the day(Reference Fernández San Juan14–Reference Ni Mhurchu, Turley and Gorton20).

Nutrition education is known to be important to promote healthy breakfast habits in young people, but there remains a need for a reliable instrument to evaluate breakfast quality(Reference Eilat-Adar, Koren-Morag and Siman-Tov21). The aim of the present study was to assess the breakfast quality of children and adolescents in the Mediterranean area and to propose a useful instrument to estimate the quality of breakfast in this setting.

Materials and methods

The study was a population-based, cross-sectional nutritional survey carried out in Granada (southern Spain) and the Balearic Islands (north-eastern Spain) between 2006 and 2008.

The population sample comprised 4332 children and adolescents aged 8–17 years registered in school censuses of Granada (73·6 %) and the Balearic Islands (26·4 %). The sampling technique included stratification according to age and sex. Municipalities in Granada and the Balearic Islands were the primary sampling units, and individuals within the schools of these municipalities were the final sampling units. Interviews were conducted in the schools.

The frequency of consumption of foods was investigated by means of a validated semi-quantitative FFQ(Reference Mariscal-Arcas, Romaguera and Rivas22–Reference Mariscal-Arcas, Velasco and Monteagudo27), classifying the consumption frequency over the previous 12 months as: never, less than once/month; once/month; 2–3 times/month; 1–2 times/week; 3–4 times/week; 5–6 times/week; once/d; 2–3 times/d; 4–5 times/d. This FFQ is divided into five sections corresponding to five meal times (early morning, mid-morning, mid-day, mid-afternoon, evening) and each section contains foods usually consumed in Mediterranean countries. Besides data on the total daily intakes of nutrients, the present analysis focused on sections 1 and 2 of the questionnaire (for breakfast and mid-morning snack), which included the following items: bread, breakfast cereals, biscuits, fruit, fruit juice, vegetables, milk, cheese, yoghurt, olive oil, butter, margarine, sugar, jam, honey and bakery products. Results were expressed as g/d. The mean portions consumed by the study population were estimated according to the usual domestic measurements or, in some cases, the amount generally considered an average portion in Spain(Reference Dapcich, Salvador Castell and Ribas Barba28, Reference Moreiras, Carbajal and Cabrera29).

Participants were identified by a six-digit number to preserve their anonymity. Sociodemographic data were gathered on sex, age, school year and educational centre. Questionnaires were administered at the school or in the young person's home by a trained dietitian between Tuesday and Friday. The dietary software program NOVARTIS-DIETSOURCE version 1·2 was used to convert foods into nutrients(Reference Jiménez Cruz, Cervera Ral and Bacardi Gascón30).

Breakfast Quality Index

The proposed index considers the foods reported (in the FFQ) to be consumed between waking and the end of the mid-morning break (i.e. ∼10.30 hours) and their nutrient content. Intakes were evaluated according to previously published guidelines for the Mediterranean diet(Reference Aranceta, Serra-Majem and Ribas7, Reference Martínez, Caballero-Plasencia and Mariscal-Arcas18, Reference Trichopoulou, Costacou and Christina31–Reference Mariscal-Arcas, Rivas and Velasco33), scoring one point each for the consumption of cereals, fruit/vegetables, dairy products and MUFA fats, one point for the intake of simple sugars <5 % of total daily energy consumption, one point for energy intake 20–25 % of total daily energy intake, one point for intake of 200–300 mg of Ca, one point for MUFA:SFA ratio above the median for the population, one point for the consumption of cereals, dairy products and fruit/vegetables together in one meal, and one point for the non-consumption of foods rich in SFA or trans fats. Scores on the proposed index scale range from 1 to 10 (Table 1).

Table 1 Breakfast Quality Index (BQI): items included and scoring (points awarded)

The statistical software package SPSS for Windows version 17 (SPSS Inc.) was used for the statistical analysis. Because application of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test showed the data to be normally distributed, ANOVA was used to compare the intakes of nutrients among age groups and to analyse the relationships between energy and macronutrient intakes and BQI score (in tertiles). Student's t test was used to compare between the sexes. P < 0·05 was considered significant in all analyses.

The study complied with the guidelines in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures were approved by the ethics committees of the University of Granada and the University of the Balearic Islands. Written informed consent was obtained from all children and their parents or guardians.

Results

Questionnaire results from the 4332 children revealed that 6·5 % of them did not consume breakfast. The proportion of non-breakfasters was highest among the 14–17-year-olds (13·0 %) and especially among the females in this age group (16·5 % of females v. 9·3 % of males, P < 0·001). Results for the 281 non-breakfasters were excluded from the analyses.

Table 2 shows the mean estimated intakes of energy and the nutrients considered in the BQI by age group and sex, based on the FFQ data on breakfast and total intakes. All intakes decreased significantly with age (P < 0·001), with the exception of MUFA:SFA (P < 0·05). Boys had higher intakes (P < 0·05) of SFA and cholesterol and girls had higher (P < 0·001) MUFA:SFA. The estimated mean breakfast energy consumption of the whole sample represented 25·02 % of the total daily energy intake. The ratio between energy intake at breakfast and total energy intake was higher in the 7–9-years-olds than in the other age groups (P < 0·001) but did not differ between the sexes (P = 0·117). Each breakfast nutrient analysed represented between about one-fifth and one-third of its total daily intake, with the exception of protein (below one-fifth) and Ca (above one-third).

Table 2 Breakfast nutrient intake (mean and standard deviation) by age group and sex and relationship with total daily intake (%): schoolchildren aged 8–17 years, Granada and Balearic Islands (Spain), 2006–2008

Mean values differed significantly by age group: *P < 0·05, ***P < 0·001.

Mean values differed significantly by sex: †P < 0·05, †††P < 0·001.

The mean BQI score of the whole population was 5·64 (sd 1·60). Stratification of the BQI scores into tertiles showed that 77·7 % of the whole population had a score of 4–7, 13·6 % a score ≥8, and 8·7 % a score ≤3. Table 3 shows the energy intake at breakfast as a percentage of total daily energy and reports the contribution of each nutrient to the breakfast energy intake, grouped by BQI tertile. All food/nutrient groups showed significant differences among tertiles. The highest energy and carbohydrate intakes and lowest protein and fat intakes (expressed as percentages of breakfast energy and total energy) were observed for BQI score ≥8, and stepwise regression analysis revealed that bakery products, bread, biscuits and breakfast cereals contributed 95 % of the energy intake among those in the third BQI tertile.

Table 3 Relationship of Breakfast Quality Index (BQI) score with energy and macronutrient intakes: schoolchildren aged 8–17 years, Granada and Balearic Islands (Spain), 2006–2008

Values differed significantly according to BQI score: ***P < 0·001.

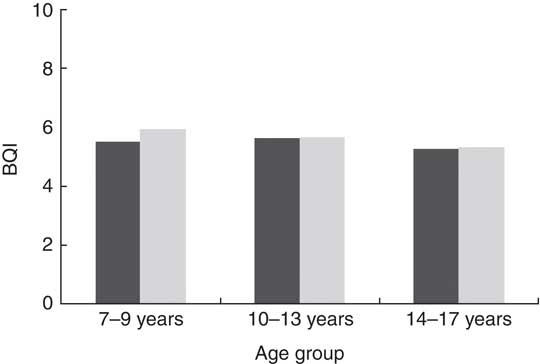

Figure 1 depicts the significant reduction in BQI score with age (P = 0·006, Spearman test). A significant gender difference in BQI score was found for all age groups (P = 0·006, t test), with the boys aged 14–17 years showing the lowest score (mean 5·28 (sd 1·55)) and the girls aged 7–9 years the highest score (mean 5·92 (sd 1·60)). The interaction of age and sex had a significant effect on BQI score (P = 0·018, two-factor ANOVA).

Fig. 1 Breakfast Quality Index (BQI) score by age group and sex (![]() $$$$

, boys;

$$$$

, boys; ![]() $$$$

, girls): schoolchildren aged 8–17 years, Granada and Balearic Islands (Spain), 2006–2008. BQI scores were significantly different between boys and girls in all age groups (P = 0·006) and decreased significantly with age (P = 0·001)

$$$$

, girls): schoolchildren aged 8–17 years, Granada and Balearic Islands (Spain), 2006–2008. BQI scores were significantly different between boys and girls in all age groups (P = 0·006) and decreased significantly with age (P = 0·001)

Discussion

Breakfast consumption by young people has reduced over the past 25 years, with a greater decline among adolescents than in any other age group(Reference Giovannini, Verduci and Scaglioni9, Reference De Rufino Rivas, Redondo Figuero and Amigo Lanza34). In the present study, 6·5 % of the children and adolescents did not take breakfast, and this proportion was higher among the adolescents, in agreement with previous reports(Reference Aranceta, Serra-Majem and Ribas7, Reference Alexy, Wicher and Kersting35, Reference Moreno, Rodriguez and Fleta36). An earlier study of Spanish children and adolescents reported that 4·1 % skipped breakfast(Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas and Ngo37), lower than some estimates of 25 % of young people in other countries(Reference Deshmukh-Taskar, Radcliffe and Liu12, Reference Lazarou, Panagiotakos and Kouta38).

A BQI was developed and applied to the 93·5 % of our study population who consumed breakfast. Higher BQI scores were associated with improvements in the relationships of macronutrients to energy intake and with improved Ca intake and MUFA:SFA. The results of stratifying BQI scores into tertiles, associated with significant differences in the intakes of all foods, lead us to propose that the first tertile (≤3 points) represents a poor breakfast, the second (4–7 points) a medium-quality breakfast, and the third (≥8 points) an adequate breakfast(Reference Van den Boom, Serra-Majem and Ribas8, Reference Kukulu, Sarvan and Muslu19, Reference Eilat-Adar, Koren-Morag and Siman-Tov21, Reference Goglia, Spiteri and Ménard39). The sole limitation to this categorization in is regard to energy intake, which is above recommendations in breakfasts scoring ≥8 points. According to this classification, significantly more children had a medium-quality (score 4–7) than a poor breakfast (score ≤3) until the age of 13 years, but the opposite was true after this age. Further research is warranted to elucidate the reasons for this trend, but a lower parental supervision of breakfast with higher age of the child may play a role(Reference Aranceta, Serra-Majem and Ribas7).

According to various authors, breakfast should supply 20–25 % of total daily energy through the consumption of cereals, fruit and dairy products(Reference Aranceta, Serra-Majem and Ribas7, Reference Van den Boom, Serra-Majem and Ribas8), to which we added the intake of simple sugars and MUFA-rich vegetable fats. We also evaluated positively the absence of SFA and trans-rich fats, due to their known relationship with CVD and other chronic non-transmittable illnesses(Reference López-Miranda, Pérez-Jiménez and Ros40–Reference Carrillo Fernández, Dalmau Serra and Martínez Álvarez42). MUFA:SFA, widely used as an indicator of the quality of fats in the diet, was also taken into account in our index(Reference Bibiloni, Martinez and Llull26, Reference Jiménez Cruz, Cervera Ral and Bacardi Gascón30, Reference Gaskins, Rovner and Mumford43). The intake of Ca was also considered, given its special importance in childhood and adolescence, when growth and bone turnover are most intensive(Reference Ambroszkiewicz, Klemarczyk and Gajewska44). It is difficult to meet dietary Ca recommendations without consuming dairy products, and it has been demonstrated that diets low in Ca and dairy products tend to be deficient in several nutrients(Reference Rafferty, Watson and Lappe45).

A recent publication on breakfast consumption and physical activity in 9–10-year-olds classified breakfasts as poor or good quality according to the consumption of respectively none/one or two/three of three specific food groups (dairy products, cereal/grain products and fruit) and analysed the relative energy intake(Reference Vissers, Jones and Corder46). The authors did not include mid-morning snacks in their survey, and account was not taken of the breakfast intake of micronutrients (e.g. Ca) or the types of fats consumed.

Glucose and insulin levels fall overnight, explaining the need to consume foods with a high glycaemic index at breakfast as an immediate and important source of energy(Reference Foster-Powell, Holt and Brand-Miller47), yielding beneficial cognitive effects and reducing feelings of tiredness(Reference Van Cauter, Blackman and Roland48, Reference Westenhoefer49). In our cultural setting, one way to satisfy glucose demands after the nocturnal fast is by consuming sugar, honey or jam, and our survey found a mean breakfast energy intake of 0·14 (sd 0·10) MJ/d from simple sugars, which represented about 2 % of total daily energy. This percentage appears consistent with the WHO recommendation that simple carbohydrates should not exceed 10 % of daily energy intake(50). Some studies have shown that breakfast foods with a high glycaemic index are more appetizing for young people and make their consumption of breakfast more likely(Reference Clark and Crockett51, Reference Harris, Schwartz and Ustjanauskas52). It has also been proposed that the faster delivery of glucose offered by a meal with high glycaemic index may confer benefits on memory functioning(Reference Smith and Foster53).

The present breakfast index was developed in a Mediterranean setting, and caution should be taken in extrapolating the results to other regions with different dietary patterns. However, our proposal could serve as a model for developing other reference breakfast indices. These results underline the need for effective nutrition education programmes in schools to encourage young people to follow a balanced diet. Families should also be targeted, given that family meal times are important for the development of healthy dietary habits among children and adolescents(Reference Pearson, Atkin and Biddle54). High-quality breakfast programmes may improve the dietary status and learning performance of young people and would be especially valuable for those who receive poor nutrition during the rest of the day(Reference Basch55).

The BQI would be an invaluable instrument in this context, allowing evaluation of the quality of the breakfasts consumed by students and the subsequent correction of any poor habits detected. It can also be applied in adults for the same purposes. The availability of a standardized score would be of major value for epidemiological studies across the Mediterranean and for studies that aim to relate the consumption of breakfast to educational performance or health status, among other variables of interest.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: This study was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Health and Consumption Affairs (Program for Promotion of Biomedical Research and Health Sciences, Projects 05/1276 and 08/1259, and Red Predimed-RETIC RD06/0045/1004); the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science (FPU Program, PhD fellowship to C.M. and M.M.B.); the University of Granada (Postdoctoral Contract to M.M.-A.); the Andalusian Regional Government (grant AGR255); and the Health Department of Granada City Council, Spain. Conflict of interest: The authors state that there are no conflicts of interest. Authors’ contributions: M.M.-A., A.P., J.A.T., and F.O.-S. conceived, designed and devised the study; M.M.-A., C.M., M.M.B., J.A.T., A.P.-A. and F.O.-S. collected and supervised the samples, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript; M.M.-A., A.P., J.A.T. and F.O.-S. supervised the study; A.P., J.A.T. and F.O.-S. obtained funding. Acknowledgements: The authors thank Richard Davies for editorial assistance.