Diets rich in fruits and vegetables reduce risk of heart disease(Reference Wang, Ouyang and Liu1,Reference Dauchet, Amouyel and Hercberg2) , some cancers(Reference Wang, Ouyang and Liu1,Reference Farvid, Chen and Rosner3) , diabetes(Reference Ford and Mokdad4,Reference Wu, Zhang and Jiang5) and all-cause mortality(Reference Bellavia, Larsson and Bottai6). Although the overall US population is under-consuming fruits and vegetables, low-income individuals consume even less(Reference Lee-Kwan, Moore and Blanck7) and also have greater risk of chronic diseases(Reference Seligman, Laraia and Kushel8) and all-cause mortality(Reference Banerjee and Radak9). Greater risk of diet-related chronic disease among low-income individuals may be partially attributed to lower nutrition knowledge(Reference Laz, Rahman and Pohlmeier10) and limited cooking skills(Reference Wolfson, Ramsing and Richardson11).

Community-supported agriculture (CSA) and other direct-to-consumer models may be a unique way to address limited nutrition knowledge and access to healthy food among low-income populations. The CSA model, brought to the USA in the 1980s from Switzerland and Japan(Reference DeMuth12), is characterised by an economic partnership between farmers and consumers, in which consumers purchase a ‘share’ of a farm’s crop prior to the growing season and receive portions of the produce grown(Reference Brown and Miller13). CSA farms can be found in all regions of the USA(Reference DeMuth12,Reference Woods, Ernst and Tropp14) . In 2015, 7398 farms sold $226 million in product through CSA sales(15) and membership has increased in the past 15 years(Reference Woods, Ernst and Tropp14). CSA members tend to be higher income and well educated(Reference Jackson and Essl16,Reference Russell and Zepeda17) , and cost is a major barrier to participation(Reference Hanson, Garner and Connor18). However, CSA are associated with higher fruit and vegetable consumption(Reference Cohen, Gearhart and Garland19–Reference Wilkins, Farrell and Rangarajan21), and participation among low-income families may promote produce intake and adoption of healthy eating patterns(Reference Quandt, Dupuis and Fish20,Reference Andreatta, Rhyne and Dery22) .

A major barrier to use of CSA produce is lack of education or experience with proper preparation methods(Reference Cotter, Teixeira and Bontrager23). While it is imperative that interventions aiming to improve fruit and vegetable consumption among low-income populations provide the skills and knowledge needed to support behaviour change, several barriers exist in implementing nutrition education to these communities. Such barriers include transportation challenges, a lack of reinforcing infrastructure and educators seen as ‘outsiders’(Reference Haynes-Maslow, Osborne and Pitts24). Perceived benefits of and barriers to attending CSA-paired nutrition education classes among low-income families have been reported by Quandt et al. (Reference Quandt, Dupuis and Fish20). Quandt et al. found barriers to be conflicting family activities and night classes, as well as frequently changing contact information. Recommendations for improvement were to partner with agencies and hold nutrition education classes at natural hubs for families(Reference Quandt, Dupuis and Fish20). However, the current literature still lacks dedicated exploration into the experiences of participants enrolled in CSA-paired nutrition education and the potential benefits.

Farm Fresh Foods for Healthy Kids (F3HK) was a randomised intervention trial for low-income families and their children. The trial partnered with twelve farms across four states – New York, Vermont, Washington and North Carolina – to implement a subsidised or ‘cost-offset’ community-supported agriculture (CO-CSA) programme paired with nutrition education. Participating farms were selected by community partner referrals. We sought farms who accepted, or were willing to accept, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits; were willing to offer weekly payment plans for participants and who agreed to participate in a sustainability plan to continue the CO-CSA programme after the intervention’s conclusion. Participants agreed to pay 50% of the CSA share and the remaining 50% was paid upfront to farms by study grant funds. The goal of F3HK was to investigate the effects of the intervention on diet, other health behaviours and local economies. Participants were randomised into the intervention or the delayed intervention control group. Participants of the intervention group received the CO-CSA and CSA-tailored nutrition education in 2016, and the delayed intervention control received the same intervention one year later in 2017.

After completion of a full season of the intervention, participants were invited to take part in focus group discussions to share their experiences with the CSA programme and nutrition education classes. The present paper aims to describe: (1) participants’ experiences with nutrition education classes; (2) barriers to attending education classes; (3) similarities or differences in perceived barriers between those who attended at least one class and those who did not attend any classes and (4) recommendations to improve class curricula and reduce barriers to attendance.

Methods

Education curriculum

The education curriculum was developed to align with locally grown produce items and state agricultural calendars(Reference Wilkins and Bokaer-Smith25–31) and with input from an advisory committee which included researchers and Cooperative Extension education representatives from each of the four states. The overall objectives of the nutrition education were to (1) address attitudes and beliefs about the value of consuming fruits and vegetables (outcome expectation); (2) improve skills and self-efficacy with respect to storing, preparing and consuming CSA produce (self-efficacy); (3) reduce potential barriers to acceptance of CSA produce and develop strategies to substitute fruits and vegetables for more energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods (barriers); (4) increase skills and self-efficacy related to preparation of CSA produce using minimal solid fat and sugar (behavioural capacity); (5) provide opportunities for participants to observe peers demonstrating newly acquired skills and share new experiences via group discussion (observational learning/modelling) and (6) provide information and strategies to help families be more active in daily life and reduce sedentary time, particularly screen time. Each farm site had nine classes that were provided during the CSA season which varied from 15 to 24 weeks. Educators completed a two-hour, web-based training on the curriculum’s organisation and content, as well as best practices for educating adults. They were encouraged to hold three classes at the beginning of the season, three classes mid-season and three classes near the end of the season. Most classes included an ‘apply’ activity that involved hands-on food preparation aimed to stimulate behaviour change in fruit and vegetable intake(Reference Hersch, Perdue and Ambroz32,Reference Reicks, Trofholz and Stang33) . Tastings did occur, but full meals were not typically provided. While lessons focused on adults, each class included child-friendly activity adaptations and materials. More details on the design and methods of the F3HK intervention have been published by Seguin et al.(Reference Seguin, Morgan and Hanson34)

The nine-lesson curriculum was implemented in each farm community during the CSA season which varied from 15 to 24 weeks. Educators were encouraged to hold three classes at the beginning of the season, three classes mid-season and three classes near the end of the season. Drawing on prior research about barriers to participation in CSA-tailored education(Reference Quandt, Dupuis and Fish20), many classes were held at natural hubs for family activities that included churches, schools, a community centre, an extension office and one of our CSA farms. In addition, research staff queried participants about convenient days and times for lessons, and educators scheduled classes to accommodate the greatest number of participants.

Recruitment and focus groups

We recruited focus group participants from families that participated in the F3HK intervention. We contacted F3HK participants via email, phone and text message to participate at the end of the first season of CSA membership (2016 for intervention participants and 2017 for delayed intervention participants). Adhering to the trial’s inclusion criteria, all participants were parents or legal guardians of one or more children aged 2–12 years. Those who had participated in a CSA in the past 3 years were excluded. Participants were asked for their annual household income. Participants who could not attend the scheduled focus group in 2016 were invited to the 2017 focus group. We asked participants to share their experiences with the intervention, including how the CSA share and education classes may have impacted at-home behaviours. In 2016, we held fourteen focus groups in November and December with a total of fifty-three attendees. In the second year of implementation, we held a further fourteen groups between September and December with a total of forty-three attendees. We held at least one focus group for each of the twelve farm sites each year. Attendance at each focus group ranged from one to eight participants. Focus group discussions lasted 60–90 min, were held in community locations and were facilitated by a trained interviewer. Prior to the groups, we conducted a facilitator training to review how to establish a welcoming atmosphere, remain neutral, ask effective probes and manage group dynamics. Participants provided written consent prior to the start of each focus group. We allowed caregivers to bring their children but did not provide formal childcare. Each participant was compensated $25. Some participants did not attend any classes but were still invited to attend a focus group and asked to speak on their personal barriers to attendance. On average, focus group participants attended 4·17 classes, ranging from 0 to 9, out of a total of nine classes. Sixteen did not attend any F3HK nutrition education classes.

We developed a semi-structured discussion guide with two parts. First, we assessed CSA access modelled on the 5A framework for access which was adapted by Caspi et al. to be specific to food access. Dimensions included availability, accessibility, affordability, acceptability and accommodation(Reference Caspi, Sorensen and Subramanian35). Findings from this discussion have been reported by White et al. (Reference White, Jilcott Pitts and McGuirt36)

Second, we inquired about participants’ experiences with, and perceptions of, the education classes themselves. The current paper focuses on description and analysis of these experiences and perceptions.

Qualitative analysis

We audio recorded the focus groups and transcribed them verbatim before uploading into Nvivo Pro version 11 (QSR International) for data management and coding. We developed an initial inductive codebook based on the questioning structure of the discussion guide. Two researchers (I.L. and L.G.) independently coded four transcripts. A third researcher (L.C.V.), who led focus group facilitation in New York, joined the other two researchers and together the team reviewed the initial coding, discussed and resolved discrepancies and developed new codes based on emergent ideas. Based on these discussions, we revised the codebook and used this revised version to recode the four transcripts and all remaining transcripts. All coding took place between March and May 2019. Inter-coder reliability was high, with observed agreement >99% and prevalence-adjusted and bias-adjusted kappa >99%. Given the high level of agreement between coded files, we analysed the data using the first author’s coding. Our analysis involved reviewing each code and summarising ideas presented. We organised the analysis in three categories: benefits of classes, barriers to class attendance and recommendations for improving classes. Themes presented in the results were drawn from each of the four participating states.

Results

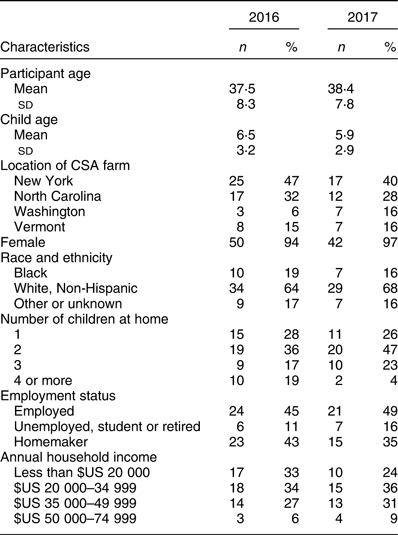

Almost all participants were female and over 60% had an annual household income of less than $US 35 000 (Table 1). We report findings according to the objectives and illustrate dominant and recurring themes with quotations.

Table 1 Demographic data for focus group adults with children (n 96) Participating in the farm fresh foods for healthy kids (F3HK) multicentre randomised intervention trial’s cost-offset community-supported agriculture (CO-CSA) programme. Focus groups were held in 2016 and 2017 and were located in nine communities in New York, North Carolina, Washington and Vermont states

Perceived class benefits

Participants described seven major benefits of class attendance: recipe ideas, caregiver cooking and food preservation skills, caregiver nutrition knowledge, improved home cooking behaviours, child knowledge and skills, sense of community and enhanced CSA experience.

Recipe ideas

Participants reported the primary benefit of the classes to be the distribution of recipes. Most participants reported that recipes helped them learn to cook unfamiliar produce and introduced different and new ways to prepare familiar vegetables. The recipes were even beneficial to those who could not attend classes; some educators emailed participants recipes in addition to handing them out in class.

‘It [the class] gave you ideas to cook with some of the [CSA] stuff… that we didn’t know how to cook.’ (NC, Farm 31)

‘I think it was most helpful that we got recipes of things that were cooked in the class, so if we missed it we could try it at home.’ (NC, Farm 32)

‘I cook radishes now [laughter], um I think I use more herbs too… because a lot of the recipes you use fresh herbs in the book that they gave us and some of the cooking classes.’ (VT, Farm 41)

Caregiver cooking and food preservation skills

Class activities were also helpful, as many participants reported that they learned cooking techniques such as stir-frying, steaming and chopping. Participants also noted that they learned food preservation techniques like freezing produce and drying herbs and that they felt more confident in the kitchen and cooked more at home.

‘Learning the different ways to steam things … it did give me ideas with ways to prepare certain things’ (NY, Farm 13)

‘Taught me how to make more stir fries like how to really incorporate more vegetables into a stir fry’ (NY, Farm 13)

‘I learned… how to cut properly. There’s a way that you’re supposed to cut things … there’s different cooking techniques, and then also how to preserve your … veggies for longer, and stuff like that.’ (VT, Farm 44)

Perceived caregiver nutrition knowledge

Many participants appreciated the activities that took place outside of the kitchen and described learning new skills and knowledge that complemented their CSA experience. For example, the grocery store tour covered calculating price based on weight and helped participants recognise cost differences based on unit price rather than sale price. Participants described how the visualisation exercises helped them understand the health risks associated with popular dishes that their families may consume when not eating at home.

‘The unit price v. the sale … and then you know how to compare, that was very helpful…to see if you’re actually getting a sale.’ (NC, Farm 32)

“So you picked the Denny’s Grand Slam and she gave you a hamburger bun and a tub of lard and said, “Okay that Grand Slam equals"… 8 scoops of lard and just visualizing it” (NY, Farm 12)

Home cooking behaviours

Several participants described cooking and eating more vegetables as a result of the cooking classes. They said classes encouraged them to cook more and to use healthier cooking techniques. Many stated feeling more confident in the kitchen and were more willing to involve their children in the kitchen at home after the cooking classes.

‘I think it opened me up to a different mindset on looking at vegetables … This way I realize “yeah, it doesn’t take that much to cook it, or bake it or fry it.”.’ (WA, Farm 22)

‘Cooking is kind of a stressful thing for me. I was always brought up, you know, one person in the kitchen. So I’ve actually learned to let the kids do things and make a mess and not be so stressed about it.’ (NY, Farm 11)

‘I use less oil…and I try to use healthier oil like…olive oil, avocado oil.’ (NY, Farm 11)

Perceived child knowledge and skills

Instructors also endeavoured to engage children in activities, such as colouring a diagram of MyPlate, and in cooking preparation, such as allowing them to cut vegetables and help clean up. Many participants reported that children found the classes to be fun and looked forward to helping to cook each week. Some parents noted that this enthusiasm translated into greater interest among their children to help cooking at home.

‘Yeah, [the educator] was really good about having her [my daughter] do things, you know, that she could do. Like chopping certain things or washing things or stirring.’ (VT, Farm 41)

‘Definitely made them want to be more involved at home. My kids want to help cook now.’ (NC, Farm 32)

Sense of community

Many participants felt a sense of community with other attendees, the instructors and the children. They noted how classes and open discussions facilitated sharing of recipes and cooking ideas and how cooking together and sharing meals reinforced a sense of comradery. Conversations during classes were described as ‘fun’, and participants exchanged contacts and made friends. Some participates noted that their children made friends with other participants’ children.

‘It was awesome. She [daughter] got to participate and that was one of my favorite things, having the community aspect of the classes because it makes the healthy food really important when we are actually gathering in one space together to share and cook a meal together.’ (WA, Farm 22)

Enhancement of the community-supported agriculture experience

Some participants reported that classes supported their CSA experience through discussions of how to use the weekly produce. However, this was only discussed at three locations. Participants at seven locations suggested that class lessons and recipes be more focused on the produce they received in their CSA shares.

‘So that was really a key to this program, was the Thursday [CSA pick-up] and the Thursday night we had the cooking, and it was the same exact thing that was in our bag. It was really nice.’ (NC, Farm 32)

‘One time I asked hey, can we figure out what to do with kohlrabi cause I’m so lost… can we do some recipes or something.’ (NC, Farm 32)

Barriers to class attendance

Participants discussed three major barriers to class attendance: personal obligations, caretaker obligations and class logistics. We did not observe notable differences in the types of barriers between participants who attended one or more classes and those who could not attend any.

Personal obligations

Most participants who did not attend any of the education classes reported work and school obligations to be important barriers to attending classes. Many of these participants described that education classes offered in the middle of the day were particularly difficult to attend due to work, and a few mentioned how education classes conflicted with their night college classes.

‘We would have loved to have done the cooking classes, but I couldn’t. I got a new job. So schedule-wise I’ve been working a lot of hours.’ (NY, Farm 12)

‘I wasn’t able to make any of the classes because I was working.’ (WA, Farm 23)

Caregiver obligations

Participants described prioritising family obligations over nutrition education classes. Among those with small children and infants, evening class times interfered with early bedtimes.

Participants with older children juggled multiple extracurricular activities after school, such as sports practices and afterschool education programmes.

‘It was hard for me because I have some [kids] in sports practice, [as a] single parent, I had to be the one to pick up and that time is around dinner time and close to time they get out of practice. So just that little group after, the little cooking class, I really had trouble sticking with that.’ (NC, Farm 32)

Early evening classes also made dinner preparations late and rushed, leaving some participants forced to order take-out or skip dinner to rush to class right after work. And although participants often sampled dishes they cooked during class, many thought that the dishes were not substantial enough for a meal and reported feeling hungry and tired during and after class.

‘Yeah it was … you know by the time [husband] got out of work and we got here we didn’t have time to cook dinner.’ (NY, Farm 12)

‘I was usually already hungry when I got there, and I’m like, I wanna hurry up and, you know, get this done so I can eat! Um, but then at the same time it usually was not very filling, and so when I got home, I was still wanting something to eat. But it was like 7:30, almost 8 o’clock. Um, so that was kind of hard to deal with.’ (NC, Farm 32)

Class logistics

Differences in class logistics also affected coordination between CSA pick-up and class times and dates. At five locations, educators scheduled classes to correspond with CSA pick-up times and locations. Participants at these sites reported this to be convenient and said they appreciated maximising their travel time in this way. For others, the distance between their home and the class location and the lack of coordination with CSA pick-up were problematic.

‘The classes were on… was it Tuesday or Wednesday? And then pickup was on Thursday and I’m like [long pause] I’m driving to [town] twice a week. So that made my commute harder.’ (NY, Farm 12)

Recommended class improvements

Participants made four distinct suggestions for improving the F3HK education classes: offer multiple classes a week, lengthen the class time, make greater use of the CSA produce in the class activities and provide childcare.

Multiple classes a week

Participants offered suggestions to resolve conflicts with work and personal schedules. However, opinions varied on whether classes should be held on weekends or weekdays. Participants suggested repeating the class lesson more than once a week, on different days and at different times:

‘It would have been nice if they were not always on the same day of the week so that if a participant can never do a Wednesday, at least there is one day that they will be able to do. Or maybe gather the availability of participants in general and then based on that pick two different days that work for most people.’ (WA, Farm 22)

Lengthen the class time

Participants recommended extending classes from 60 to 90 or 120 min. Many felt that classes were rushed, especially when they were involved in cooking activities and socialisation. Several participants suggested that eating and socialising should be included in an extended class period so that sufficient time could be given to the curriculum and activities and extra time at the end could serve as a ‘buffer’ for community building.

‘I think the class should be scheduled for an hour and a half because really the last 15 minutes was eating the food and coming back together as a community. So having that scheduled into the class time so that we didn’t have to rush off … having an extra buffer of time, having that scheduled in.’ (WA, Farm 22)

Greater use of community-supported agriculture produce and pantry staples

Participants strongly suggested that cooking classes focus more explicitly on the produce included in the weekly CSA share. Additionally, demonstrating recipes that only required pantry staples in addition to CSA items was important. As one participant explained:

‘… we were making something that I would have to go buy all the ingredients on top of the CSA. So I was like this is not okay for me. For me I thought it was going to be like a cooking class for adults where you go and use the things from your box to make.’ (NY, Farm 11)

Providing childcare

Some participants with small children reported that providing childcare would have been a significant incentive for attendance. Although children were welcome to attend, these caregivers raised concerns over children being distracting or not sufficiently accommodated in classes and suggested incorporating more structured activities for children so the adults could focus on the class content. Although the curriculum outlined ways to involve children in some discussions and cooking activities, young children were often left unoccupied.

‘…my other two girls were not as excited cause they’re a little younger. I think standing there for a long time was a little challenging for them.’ (NY, Farm 13)

‘Yeah, they got antsy because they got bored. If you have some kind of organized activity for the kids while we were doing our portion, I think would’ve been great.’ (VT, Farm 44)

Discussion

This qualitative study of low-income participants in a CO-CSA intervention investigated participants’ perceived experiences of nutrition education classes, barriers to class attendance and recommendations for class improvements. Some of the findings align with previous evaluations of nutrition education classes. To our knowledge, this is only the second peer-reviewed paper to examine perceptions of nutrition education designed to complement cost-offset CSA programmes, and our findings generally are consistent with that smaller study(Reference Quandt, Dupuis and Fish20). Below we highlight several unique findings, including those that may help to inform future interventions with similar goals and target populations.

Participants described five benefits of the education classes that aligned with prior research: recipe ideas, caregiver cooking and food preservation skills, improved perceived child knowledge and skills, perceived caregiver nutrition knowledge and improved home cooking behaviours. Our findings are congruent with other studies that find recipes and cooking lessons to be effective in helping low-income families enhance their cooking skills(Reference Birmingham, Shultz and Edlefsen37,Reference Pooler, Morgan and Wong38) and added support for the inclusion of food preservation among the food preparation skills taught. Perceived changes to children’s knowledge and skills as a result of nutrition and cooking education also align with prior research(Reference Hersch, Perdue and Ambroz39). Non-cooking activities, such as a grocery store tour and food content visualisations, contributed to perceived increases in caregiver nutrition knowledge. Grocery store tours have been shown to improve knowledge and intention to consume more fruits and vegetables(Reference Nikolaus, Muzaffar and Nickols-Richardson40,Reference Jung, Shin and Niuh41) and are widely used in healthy eating promotion programmes(Reference Pooler, Morgan and Wong38,Reference Jung, Shin and Niuh42) such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program-Ed(Reference May, Brady and Van Offelen43).

Participants also noted two benefits not reported in prior research: a sense of community and an enhanced CSA experience. There was a sense of community with other participants and the instructors, especially around open discussion of their CSA experience and sharing food. Sharing meals after cooking lessons may have contributed to social bonding, which makes individuals feel better about themselves and closer to those around them(Reference Dunbar44). To our knowledge, no other study has reported social eating as a benefit to cooking classes and nutrition education. Future interventions should consider the inclusion of community bonding activities for participant enjoyment and retention.

The perception that cooking and tasting activities enhanced the CSA experience was only reported as a benefit by participants at three locations where educators incorporated the current week’s CSA produce into the class lesson and featured recipes. Although class content had been developed to align with locally grown produce items and state agricultural calendars(Reference Wilkins and Bokaer-Smith25–31), recipes did not always use items in the participant CSA share for that week. Dannefer et al. showed that pairing nutrition education with shopping at a farmers’ market increases willingness to try new fruits and vegetables(Reference Dannefer, Abrami and Rapoport45). Acceptability of introducing new foods from the CSA shares to their families was a focus group theme(Reference White, Jilcott Pitts and McGuirt36); thus, it would be beneficial for educators to have knowledge and access of specific weekly CSA contents to highlight the produce in class activities. To this end, F3HK educators were offered CSA shares alongside participants during the second year of the intervention (2017). Even with this change, featured produce sometimes differed from participants’ share contents either because class participants received shares from different farms or the share contents differed within the same farm, preventing perfect alignment with lesson content and requiring educators to adapt lessons with little notice. However, direct, advance coordination between educators and farmers may not be realistic given farmers’ chaotic schedules and the unpredictability of the growing season. Educators’ use of passive means (e.g. farm newsletters or social media) may be another mechanism by which to improve coordination. Future studies should explore strategies for improved coordination and for bolstering consumers’ adaptability to the flexible shopping and cooking routines required when relying on the local food system.

Participants reported conflicting work and family obligations as primary challenges to class attendance, citing work schedules, night classes and children’s extracurricular activities as examples. Accommodating different schedules and finding a class time that worked for all participants was a major theme for Slusser et al. (Reference Slusser, Prelip and Kinsler46) Quandt et al. previously reported on barriers to low-income participants’ attendance at educational sessions paired with a CSA programme and found similar challenges(Reference Quandt, Dupuis and Fish20). We sought to overcome barriers identified by Quandt et al. regarding conflicting family activities and scheduling(Reference Quandt, Dupuis and Fish20) by surveying families to identify preferred class times and locations at enrollment. However, there were several months between enrollment and the start of classes, so their availability may have changed. Furthermore, no prior studies have reported that offering education sessions in the evening is a barrier to attendance because they conflict with dinnertime. Given that participants reported a sense of community around shared food and a desire for longer sessions, future interventions of this nature may consider allocating more time to eat and providing meal-sized recipe portions.

Two additional recommendations to enhance education classes were offered by participants: offering each lesson more than once at different times and integrating childcare. The resource-intensive nature of these recommendations and limited funding and transportation for educational programmes in rural communities(Reference Haynes-Maslow, Osborne and Pitts24) may impede their feasibility. Participants found it convenient to attend classes when they aligned with weekly CSA pick-ups. Such alignment may be the most efficient way to create convenience for participants, and the curriculum could be further refined to ensure engagement opportunities for children of diverse ages.

Given that lack of knowledge about CSA(Reference Hanson, Garner and Connor18), how they operate(Reference Cotter, Teixeira and Bontrager47) and how to cook CSA produce(Reference Cotter, Teixeira and Bontrager23) are major barriers to CSA participation among low-income families, integrating nutrition and cooking education with cost-offset CSA access has potential for greater participant benefit. Participant-reported education class benefits, such as recipes and improved cooking behaviours, may have been facilitated by the accessibility and affordability of produce in CSA shares(Reference White, Jilcott Pitts and McGuirt36) since access to produce are known barriers to healthy eating(Reference Eikenberry and Smith48–Reference Pollard, Kirk and Cade50) and behaviour change(Reference John51) in low-income families. Thus, researchers should continue to explore the feasibility and impact of interventions that combine food access with skill building and behaviour change-supporting education. However, lack of community and financial support has been a major barrier for health interventions in low-income and rural communities(Reference Haynes-Maslow, Osborne and Pitts24,Reference Barnidge, Radvanyi and Duggan52) . Therefore, online classes that do not require infrastructure or transportation may be more feasible.

Strengths of this study include the multi-site design, which allowed for a diverse sample of participant perspectives from four geographically diverse states. Standardised training of focus group facilitators aided in consistent data collection. Having multiple co-authors develop the codebook and double code the transcripts provided a wide perspective of the data and lent reliability and validity to the final codes and themes. Study limitations included poor focus group turnout. In 2016, 54% of all F3HK participants attended focus groups, and, in 2017, 42% attended a focus group. This limited generalisability of our findings. Individuals who did not attend focus groups may have faced unique challenges to class attendance not captured in these focus groups. Additionally, although focus groups allowed for dialogue among participants, they limited our ability to analyse any relationship between individual and household characteristics, such as occupation or number of children, and reported benefits, barriers and recommendations. Lastly, the potential of social desirability and recall bias may have exaggerated perceived benefits of the intervention.

Conclusion

The CSA model is an alternative mode of accessing produce that has the potential to support fruit and vegetable consumption among low-income families. Participants believed that pairing nutrition education classes with a cost-offset CSA programme improved their own knowledge, food preparation skills and cooking habits, as well as knowledge, skills and habits of their children. Future interventions would benefit from better coordination with dynamic local growing cycles for maximal integration of unfamiliar CSA produce into lesson content. Coordinating classes with CSA pick-up and offering childcare may facilitate enrollment and retention in food access interventions that seek to incorporate locally sourced foods into family focused educational activities.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank Grace Marshall, Judy Ward and Brian Lo of Cornell University for their support of this work. Financial support: This research was supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), under award number 2015-68001-23230. USDA had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: R.A.S., L.C.V., K.L.H., S.B.J.P., J.K., A.S.A., M.S. and I.L. conceived the study; R.A.S., J.K., E.H.B., M.S. and W.W. participated in data collection; I.L., L.G. and L. C.V. developed the coding approach; I.L. and L.G. coded all data; I.L., L.G., K.L.H. and S.B.J.P. analysed data and interpreted themes; all authors provided critical feedback on data analysis and interpretation and manuscript preparation. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Vermont (CHRBS 16-393) and Cornell University (protocol ID #1501005266). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.