Breast-feeding is one of the top interventions for reducing under-five mortality and improving human development(Reference Requejo, Bryce and Barros1). The promotion, protection and support of breast-feeding are key components of the Nurturing Care Framework, which provides an actionable plan focusing on children’s social, educational and health needs in order to advance early childhood development(2). Furthermore, the benefits of breast-feeding on maternal and child health, food security, education, health equity and environmental sustainability make breast-feeding an essential aspect for meeting the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals(Reference Victora, Bahl and Barros3,Reference Rollins, Bhandari and Hajeebhoy4) .

Despite the benefits and cost savings of breast-feeding, Mexico has one of the lowest rates in Latin America, with an exclusive breast-feeding rate of only 28·6 %(5). Indeed, exclusive breast-feeding in Mexico’s low-income, rural and indigenous communities is quite suboptimal and needs to be understood in the context of the profound epidemiological and nutritional transition that Mexico is experiencing(Reference Gutierrez, Rivera-Dommarco and Shamah-Levy6,Reference González de Cossío, Escobar-Zaragoza and González-Castell7) . The percentage of the population in Mexico that self-identifies as indigenous is 21·5(8). Almost 70 % of the indigenous population live in poverty, 43 % have not completed primary education and 55·2 % work in low-skilled manual jobs(9,Reference Solís, Güémez Graniel and Lorenzo Holm10) .

Previous studies have shown that economic development in indigenous communities generates changes in breast-feeding practices(Reference González de Cossío, Escobar-Zaragoza and González-Castell7,Reference McKerracher, Nepomnaschy and Altman11,Reference Rodríguez and González12) . The speed at which these changes occur depends on the socio-cultural context. For example, in some indigenous communities, the duration of exclusive breast-feeding is associated with mothers’ adherence to social norms, while the overall duration of breast-feeding is impacted by market integration and individual factors(Reference McKerracher, Nepomnaschy and Altman11). Such contextual differences can explain why certain social changes have led to the deterioration of exclusive breast-feeding practices in Mexico’s indigenous communities(Reference González de Cossío, Escobar-Zaragoza and González-Castell7).

Major social changes underlying the epidemiological and nutritional transitions in rural and indigenous communities have been linked with an increased use of ultraprocessed foods, including infant formula(Reference Rivera, Barquera and Campirano13), and can lead to the perceptions that formulas are ‘modern’ and equal to or better than breast milk(Reference Rollins, Bhandari and Hajeebhoy4,Reference Baker, Smith and Salmon14,Reference Piwoz and Huffman15) . The infant feeding industry has played a major role in promoting a formula culture as increased availability and large-scale promotion of formula negatively impact breast-feeding rates(Reference Rothstein, Caulfield and Broaddus-Shea16). Infant formula companies are now heavily marketing their products in low- and middle-income countries due to their rapid economic growth and higher fertility rates and population densities.

There is limited research on how individual and social factors have interacted to influence infant feeding practices across low- and middle-income countries. Additionally, infant feeding decisions have generally been seen through a biomedical lens that places all the responsibility or even blame for not breast-feeding on mothers(Reference Rodríguez and González12,Reference Olza, Ruiz-Berdún and Villarmea17) . This is concerning as research has shown that improving breast-feeding rates requires support from society at large, including family, health professionals and employers, and major structural changes in health and social policies(Reference Victora, Bahl and Barros3,Reference Rollins, Bhandari and Hajeebhoy4) . Thus, interventions to promote breast-feeding must be based on a socio-ecological framework (SEF)(Reference Bronfenbrenner18) which not only focuses on individual factors but also on the mothers’ interpersonal relationships, the institutions with which they interact and the social and cultural norms in which these operate. When a SEF is used, factors that may have been missed when using more individualistic models can be identified, such as sexism, racism and discrimination(Reference Rodríguez and González12,Reference Johnson, Kirk and Rosenblum19) .

Mexico has a historical debt with indigenous populations as they have been grossly neglected by government policies and the healthcare system. As a result, they often lack access to quality health care that is respectful of their cultures. In Mexico, there are sixty-eight indigenous groups, each with its own native language(8). It is important to study the conditions that occur in different indigenous groups and not generalise the findings obtained from one community to another. Given the limited infant feeding research focusing on indigenous groups in Mexico, we were interested in better understanding the multi-level factors that affect infant feeding practices in communities with a strong presence of indigenous groups. Thus, our objective was to explore the factors that influence formula use in two rural, indigenous communities in Mexico where formula use has rapidly increased in recent years. The study was designed based on the SEF with the expectation that it could inform future interventions targeting highly vulnerable populations.

Methods

Study sites

For this study, we worked in the State of Mexico, which is located in the centre of the country and has almost 15 million people, 9·1 % of which identify themselves as indigenous(20). The State of Mexico has a Human Development Index of 0·74 and a level of inequality evaluated through the Gini coefficient of 0·42, indicating the strong presence of social inequities(21). Although the state has a relatively higher economic development than the rest of the country, extreme poverty ranges from 21 to 49 % across disadvantaged municipalities(21). Twelve percentage of its localities lack basic dwelling services, and 18 % lack food access(21). The two communities included in this study were Santa Ana Nichi and Ganzdá, which were selected by Un Kilo de Ayuda (UKA), a national non-profit organisation with whom we partnered for this study. UKA selected these sites due to their previous work in both communities. Santa Ana Nichi has a population of 1213 people, of which 26 % are indigenous, with the majority being Mazahua; Ganzdá has 2433 inhabitants of which 34 % are indigenous, mostly Otomí(20,21) .

In Mexico, people with formal jobs have social security that offers health services. Until 2019, people who did not have social security could join the Seguro Popular social programme. In Santa Ana Nichi and Ganzdá, 73–75 % of people were affiliated with Seguro Popular (20), which provided prenatal, postpartum and neonatal care services. The women of these communities could also receive maternal care through private clinics (some affiliated with pharmacies), traditional healers or UKA facilities. The promotion and support for breast-feeding were provided by Seguro Popular, UKA, and the government’s conditional cash programme, Prospera.

Design and participant selection

As individuals consider adopting a new behaviour, their lived experience must be considered within a SEF to interpret its determinants(Reference Spencer22,Reference Beasley23) . Qualitative methods are essential for identifying such determinants(Reference Harris, Gleason and Sheean24). Therefore, we conducted interviews, focus groups and observations with parents, grandparents and healthcare providers. Participants were selected through purposive sampling and were approached in areas with high population density (i.e. plazas, waiting areas in clinics). Inclusion criteria consisted of mothers, fathers and grandparents of children 2 years of age or younger and healthcare providers who attended to mothers and infants (physicians, nurses, health workers and traditional healers). This study is reported as per the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research checklist(Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig25).

Data collection

Focus groups and interviews

Interviews and focus groups were conducted in Spanish by four of the female authors between June and July 2018. All interviewers were trained in qualitative research methods and were native Spanish speakers. Interviews lasted between 10 min and 1 h, while focus groups lasted between 40 and 50 min each. About 40 % of the recorded interviews lasted 20 min or more. A demographic questionnaire was administered at the end of the interviews and focus groups. The number of interviews and focus groups conducted were enough to reach data saturation.

Script guide

The interview and focus group guides were semi-structured, and their design was based on the SEF (Appendix 1). UKA reviewed these guides to ensure cultural appropriateness. The guide for mothers explored: (1) prenatal experiences; (2) infant feeding practices before/after 6 months; (3) infant feeding practices in the community; (4) benefits of breast-feeding and (5) work and school. Similar topics were included in the guides for fathers, grandparents and healthcare providers as well as additional topics that were applicable to these groups. For example, the guide for healthcare providers explored: (1) protocols surrounding pregnancy and deliveries; (2) breast-feeding recommendations and (3) formula industry practices.

Observations

Direct, non-intrusive observations during interviews were carried out to further understand the factors affecting breast-feeding practices. While no structured guides were used for this process, we wrote down any especially noteworthy exchanges that we wanted to make sure were reflected on the interview transcripts. We also visited pharmacies, clinics and hospitals in each community to note the brands, prices and visibility of infant formulas being sold.

Data analysis

Focus groups and interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim by native Spanish speakers. Participants who chose not to be recorded allowed the researchers to record their notes from the interviews either as notes or audio. The latter were also transcribed verbatim. The first author reviewed all recordings and transcripts to ensure quality and accuracy. Data analyses were conducted in two stages. First, two female authors manually analysed the transcripts independently using thematic analysis(Reference Leech and Onwuegbuzie26). They developed a codebook using emergent concepts drawn from the texts, which was used to assign codes to the transcripts. The codes were then grouped into larger themes. When differences between the first two coders were identified, they were discussed until a consensus was reached.

In the second stage of analysis, two male authors analysed sixteen transcriptions (20 % of interviews) on Dedoose, a web application for qualitative and mixed method analysis (Dedoose, LLC). These transcriptions were randomly selected and were representative of all participant groups. Analysis from the second set of coders was highly consistent with the initial analysis, and additional observations were integrated into the final results. Key quotes from the transcripts were identified to serve as evidence for each theme and were chosen to represent the various participant groups. All analysis was done in Spanish to maintain meaning.

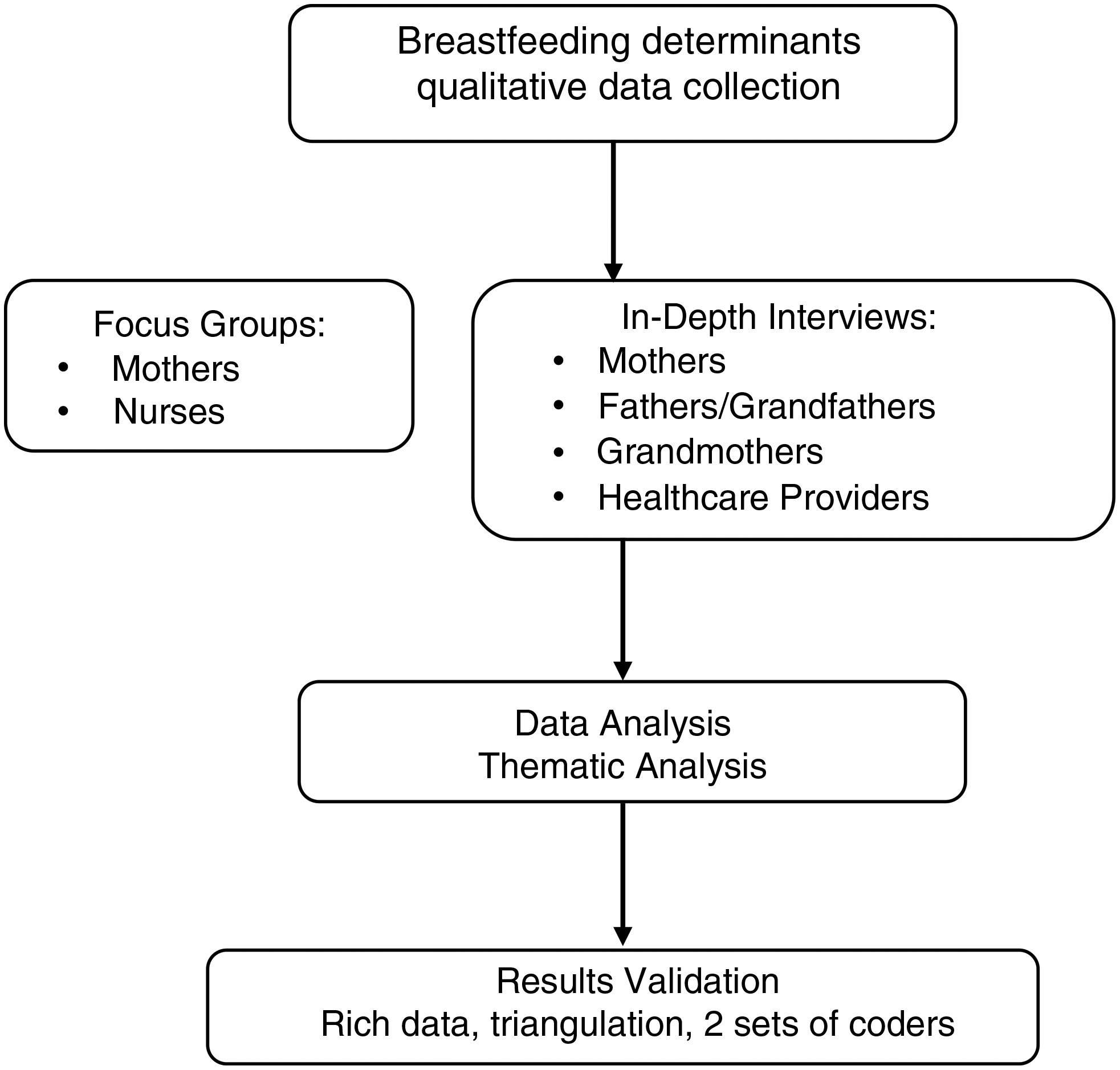

Figure 1 summarises the data collection, analysis and validation process. To maximise the validity of our findings, we used a rich data (verbatim transcripts and descriptive notes) approach and data triangulation strategy(Reference Maxwell27,Reference Maxwell, Bickman and Rog28) . The latter was done at different levels by having: (1) multiple sources of information provided by mothers, family members and healthcare providers; (2) different methods for data collection through interviews, focus groups and observations and (3) four data coders with different genders and backgrounds (medicine, psychology, community nutrition and child development).

Fig. 1 Flow chart for data collection, analysis and validation

Results

In total, we conducted fifty-nine interviews with sixty-three individuals and two focus groups with eleven individuals for a total of seventy-four participants (twenty-five mothers, twelve fathers, two grandfathers, eleven grandmothers and twenty-four healthcare providers). There were a few combined interviews: two of the interviews were with a mother and a grandmother, one interview was with two healthcare providers and one interview was with a mother and a father. We included grandfathers in the fathers’ category rather than with grandmothers due to limited availability of grandfathers and the unique influence of grandmothers on breast-feeding. Forty-nine participants were from Santa Ana Nichi and twenty-five from Ganzdá. Thirty-four percentage of participants spoke or understood an indigenous language, and all participants were fluent in Spanish. The median age of the family participants’ youngest child was 16 months. Both focus groups took place in Ganzdá; one with five mothers took place in a community centre, while one with six nurses was conducted in the hospital after the nurses’ shift. A summary of participants’ sociodemographic characteristics is found on Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of participants from indigenous communities, Santa Ana Nichi and Ganzdá, Mexico

* Percentage is for individuals with known information.

Table 2 Sociodemographic characteristics of healthcare providers from indigenous communities, Santa Ana Nichi and Ganzdá, Mexico

* Percentage amongst medical doctors.

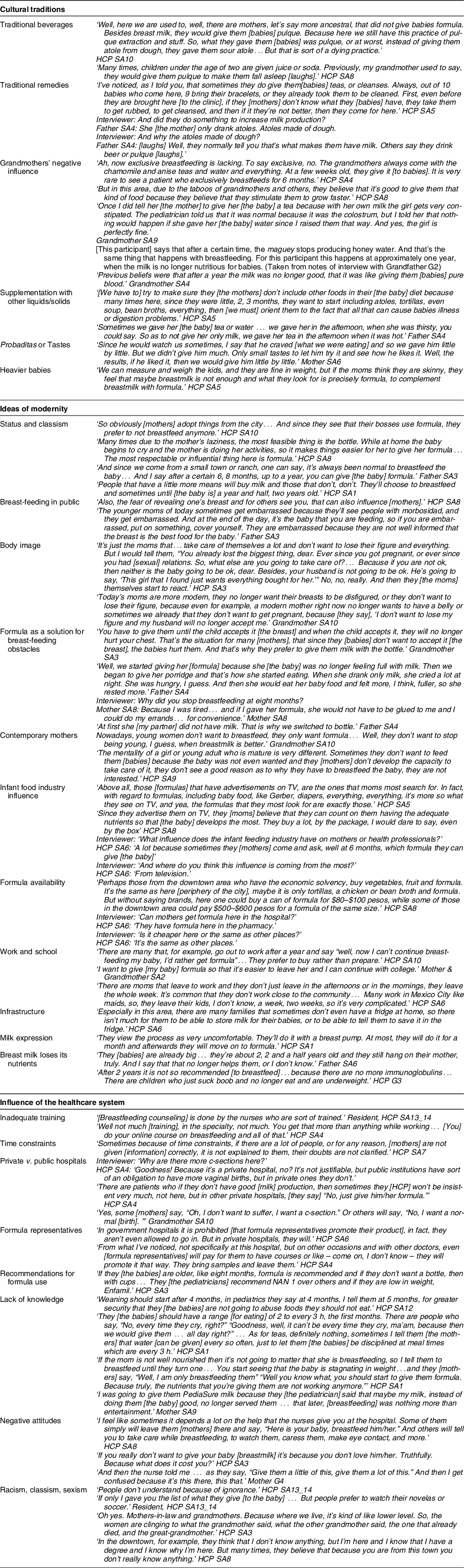

Overall, data analysis revealed three main themes: cultural traditions, ideas of modernity and the influence of the healthcare system. Collectively, these themes provided a cohesive narrative of breast-feeding practices in these two communities. We found that breast-feeding was the norm in both communities and mothers and their family members believed that breast milk was the best source of nutrition for infants. Many respondents mentioned the immunological benefits of breast-feeding, as they had witnessed that breastfed children became sick less often and they indicated the emotional bond that breast-feeding creates between mother and child. In addition, many mothers and grandmothers stated that breast-feeding was a responsibility that one must assume and continue despite the pain and difficulties it can bring to the mother. Despite this, we observed that cultural traditions and certain healthcare practices often resulted in decreased exclusive and overall duration of breast-feeding. Recent social and economic changes in the communities have also led to negative connotations about breast-feeding related to ideas of modernity, especially for younger mothers. Together, such influences appeared to facilitate a preference for formula. A summary of participants’ key quotes by themes can be found on Table 3.

Table 3 Themes, Subthemes and exemplary quotes

Cultural traditions

While breast-feeding was considered the norm in both communities, we identified several cultural beliefs and traditional practices that undermined exclusive breast-feeding. One of the most common practices was the addition of liquid and solid foods to the infants’ diets at 2–3 months of age, sometimes earlier. The reasons were varied, such as giving babies water for hydration or teas to alleviate discomforts like empacho, or indigestion. Such traditions were greatly propagated by the children’s grandmothers, whether paternal or maternal, as they often lived close to the mother. Some grandmothers recommended adding water, teas or atoles (corn-based drinks) to the infant if they perceived that the mother did not produce enough milk or to cleanse the babies’ bodies. Grandmothers also endorsed giving solid foods to provide nutrients and promote growth. Additionally, some believed that over time, a point was reached when breast milk was no longer enough and could even turn into feeding the baby with blood.

This need to introduce various foods to the infant early in life may be related to a frequently reported idea that breast milk needed to be supplemented. Infant formula was often mentioned as a good alternative to breast milk because it was thought to contain special nutrients that stimulate growth and development. Similarly, many participants mentioned the idea that chubbier babies were healthier. Mothers worried when they thought their babies were ‘too skinny’ or were not gaining sufficient weight, leading them to believe that they needed to supplement with formula. Respondents also mentioned that at times, the babies seemed to crave the other foods that the family ate, so mothers would feed their babies probaditas, or small tastes, to decrease their craving.

Another reason why mothers did not breastfeed exclusively was the perception of insufficient milk, as many mothers reported that their milk did not always meet their babies’ needs. Participants indicated that the lack of milk was often due to the lack of foods or nutrients in the mother’s diet (teas, atoles, Brewer’s yeast), the cold or the effect of ‘bad vibes,’ such as the mal de ojo, or evil eye. The prevention of and treatment for insufficient milk included protection with amulets, garlic braids, cleanses and temazcales, or ceremonial saunas. These treatments could also be used to heal babies’ discomforts such as empacho. A general practitioner mentioned that 90 % of babies arrived at the doctor’s office with a ‘pulserita’ (a traditional amulet in the form of a red bracelet) and had already been taken to a cleanse or traditional massage to heal their empacho. When such traditional treatments did not work, families then resorted to medical care.

An interesting finding was the meaning assigned to some traditional foods such as those derived from corn (atole) and maguey, or agave plant (pulque, an alcoholic drink). Participants indicated that both atole and pulque could help mothers who did not produce sufficient milk and babies who experienced empacho. Knowledge about the preparation of pulque was used as an analogy for the changes that breast milk undergoes after time, in the same way as the syrup of the maguey. One participant also mentioned that previously they gave babies pulque and now they gave them juice or soda, ‘as long as they are quiet.’

Ideas of modernity

We found that negative messages about breast-feeding were becoming more prevalent in these communities, most of them related to ideas of ‘modernity’. Several participants referred to contemporary mothers as ‘modern’ who had different priorities than mothers in the past. These new priorities may have been introduced by television and social media and as more women began working in nearby big cities. As part of this transition into ‘modern’ life, infant formula became more popular. Many participants associated with the use of formula were related to a higher socio-economic status, embodied by the women seen feeding formula on television (generally white) and in cities like Mexico City. On the other hand, several participants reported that breast-feeding was for ‘small-town people’ who did not have the money or status to afford formula.

As these communities became more modern, changes in the workplace began to take place. Most mothers worked at home (housework and childcare) and some worked outside in nearby places where they could be in close proximity to their babies and continue breast-feeding. However, due to social and economic changes, more women began working in nearby cities, mainly as domestic workers. For them, it was difficult to take their babies to work, as most of them left for the weekdays and only returned home on weekends. This led to a discontinuation of breast-feeding, either because it was difficult to continue with the baby’s sucking stimulus or because mothers were influenced by observing formula use by their employers and other women in the city. To further complicate the continuation of breast-feeding in the workplace, several participants indicated that milk expression was very difficult and a good proportion of women did not have the infrastructure to keep milk refrigerated.

The relationship of women with their bodies appeared to change as their environments became more ‘modern.’ Participants perceived that Western beauty ideals could not be achieved with breast-feeding as this could deform women’s bodies, making formula the better option. In addition, breasts were often hypersexualised, and several participants indicated that some women believed that if their breasts were deformed, their husbands would no longer accept them. These ideas were more prevalent in younger women who were more likely to feel uncomfortable when breast-feeding in public.

Additionally, formula was seen as a convenient way to navigate modern changes in a mother’s life. For example, many family members indicated that ‘modern’ mothers were not willing to endure any painful discomfort associated with breast-feeding and instead preferred to feed their babies with formula. Replacing breast-feeding with formula use was also seen as advantageous for younger mothers as it allowed them to continue schooling and complete their daily activities.

Regarding the duration of breast-feeding, most women in these communities breastfed for around 18 months. However, breast-feeding up to 2 years or more was deemed improper as some believed that babies become ‘too old or big,’ which could lead to dependency. Others believed that breast milk lost its nutrients after a certain period of time and that other foods were better for the growth of babies.

Many healthcare providers believed that the infant food industry had a significant influence on mothers, especially as access to television and social media increased over time. Particularly, television commercials had a great impact on infant feeding practices, and mothers always asked providers about the formulas that were most heavily advertised. The availability of formula was also increasing, and we found formula in most pharmacies, clinics and hospitals. Even the director and paediatrician of a hospital shared that their pharmacy sold formula for the same price as other places in town. The availability of formula also depended on the neighbourhood location, which was a proxy for the socio-economic status of the households. A healthcare provider indicated that families near the centre of town could afford and find more expensive formulas, while families in the peripheries continued to breastfeed.

Influence of the healthcare system

The healthcare system impacted breast-feeding practices in various ways. We noted certain practices that hinder breast-feeding, such as caesarean sections and the use of formula. Respondents stated that in many hospitals, especially private ones, mothers have the choice of vaginal birth or caesarean section. Indeed, we noted that women were having fewer vaginal deliveries and more caesarean sections – especially in private clinics. One gynaecologist indicated that mothers who have caesarean sections have delays starting breast-feeding, leading to formula use. Furthermore, healthcare providers mentioned that public hospitals are more insistent with mothers about breast-feeding, while private hospitals are more lenient about providing formula. Moreover, formula representatives increased availability by providing samples to physicians. While this was a bigger issue in private hospitals, many physicians who worked in those private hospitals also held positions in public ones, which could influence their practice anywhere they worked.

In addition, healthcare providers reported a lack of training and education about breast-feeding, leading to insufficient knowledge to support mothers. One gynaecologist stated that breast-feeding support for mothers was mostly given by nurses, who were ‘sort of trained.’ Furthermore, many healthcare providers indicated not having sufficient time to clarify mothers’ doubts or give adequate lactation counselling. This limited training and time constraints led many providers to give erroneous information to mothers. For example, some providers indicated that breast milk was not a sufficient source of nutrition, some recommended establishing feeding schedules instead of free demand, and others reported that after time, usually 6 months, breast milk lost its nutritional properties and formula needed to be given. Some providers even recommended certain brands of formula for different needs.

We also noted that a significant proportion of healthcare providers shared their negative attitudes towards breast-feeding with mothers. Many providers often made recommendations to use formula instead of breast milk, and at times described breast-feeding as ineffective. This unfavourable view of breast-feeding could be partially explained by the lack of practical experience on the subject. Some healthcare providers acknowledged their own difficulties in breast-feeding their children, mentioning that they understood why their patients could not do it either. Furthermore, the exposure to diverse healthcare providers led to mothers receiving confusing and/or contradictory messages.

Last, the lack of support from healthcare providers was further aggravated by racist, classist and sexist ideas. The majority of healthcare providers had ‘higher status’ profiles that differed greatly from those of people from these rural and indigenous communities, thus creating a cultural and social shock which made adequate and empathetic communication difficult.

Discussion

In these rural and indigenous communities of Central Mexico, we found infant feeding beliefs, attitudes and practices consistent with an advanced epidemiological and nutritional transition in the context of ‘modern life’ in a high middle-income country. While social norms still favoured breast-feeding, we found several cultural traditions that hindered exclusive breast-feeding. We also documented beliefs that formula was associated with modernity and higher social status, facilitating women to work outside the home and maintain a body image consistent with Western standards of beauty. Several healthcare practices further fostered the preference for formula.

We identified the prevalent use of formula associated with messages of its compatibility with modernity from the infant feeding industry and from society in general. The idea that formula can be used to ‘complement’ breast milk may have a strong penetration in these communities due to an already established belief in early supplementation of breast milk with foods such as teas, atoles and pulque. Formula was also promoted as the best solution for a modern lifestyle that could solve the various obstacles mothers faced with breast-feeding. For example, many mothers mentioned beliefs that their milk was not adequate or sufficient, which is highly consistent with previous studies conducted in Mexico(Reference Mohebati, Hilpert and Bath29,Reference Segura-Millán, Dewey and Perez-Escamilla30) and globally(Reference Safon, Keene and Guevara31,Reference Pérez-Escamilla, Buccini and Segura-Pérez32) . Some mothers believed that they did not produce enough milk, that their babies did not like their milk or that after the babies drank their milk, they remained hungry, experienced colic or did not sleep well. Formula was then viewed as a solution for these issues. Consistent with previous studies(Reference Chopel, Soto and Joiner33–Reference Williamson, Leeming and Lyttle35), younger and first-time mothers had the most difficulty with breast-feeding possibly because they had lifestyles that were incompatible with breast-feeding (i.e. work), had less experience breast-feeding and were under more pressure to not breastfeed due to stigmatisation and body image(Reference Chopel, Soto and Joiner33,Reference Anderson, Damio and Himmelgreen36,Reference Naanyu37) . In our study, younger mothers were more subject to feeling embarrassed to breastfeed in public due to morbosidad (morbid curiosity), consistent with previous studies(Reference Bueno-Gutierrez and Chantry38). All of these obstacles can lead women to feel uncomfortable with breast-feeding and instead resort to formula(Reference Bueno-Gutierrez and Chantry38,Reference Schmied, Olley and Burns39) .

Previous studies have observed similar infant feeding transitions, where the consumption of formula begins in high-income groups and then ‘trickles down’ to low-income groups(Reference Baker, Smith and Salmon14,Reference Barennes, Empis and Quang40,Reference Cattaneo41) . A study in Laos found that mothers in rural areas were more likely to breastfeed exclusively and less likely to use breast milk substitutes, while breast-feeding rates decreased in areas near bigger cities(Reference Barennes, Empis and Quang40). The consumption of formula has been positively correlated with higher income within and between low- and middle-income countries, and as countries become more developed, measures to protect breast-feeding should be implemented, particularly among the poorest communities(Reference Anderson, Damio and Himmelgreen36,Reference Neves, Gatica-Domínguez and Rollins42,Reference Mitra, Khoury and Hinton43) .

Studies on acculturation and migration have shown mothers’ adaptations from breast-feeding in more traditional and rural environments to formula use in more modern and urban ones(Reference Schmied, Olley and Burns39,Reference Singh, Kogan and Dee44) . One meta-ethnographic study showed that migrant women were often exposed to messages from the media and healthcare providers promoting formula as convenient, providing mothers with the freedom to ‘get on with [their] lives’ and avoid the embarrassment of breast-feeding in public(Reference Schmied, Olley and Burns39). Furthermore, the increased visibility of infant formula in the new environments of migrant women affected their socio-cultural expectations and practices(Reference Schmied, Olley and Burns39).

Western standards of beauty can further influence infant feeding practices, as having body image dissatisfaction increases the risk of abandoning lactation(Reference Morley-Hewitt and Owen45). One study in Mexico found that for each one-unit increase in the body image dissatisfaction score, the odds of breast-feeding decreased by 6 %, a decrease that was even greater among obese and indigenous women(Reference Bigman, Wilkinson and Homedes46). These effects of body image dissatisfaction on lactation can be particularly dangerous in countries experiencing rapid epidemiological transitions, where the high prevalence of obesity further increases the risk for body image dissatisfaction and decreased lactation(Reference Bigman, Wilkinson and Homedes46–Reference Swanson, Keely and Denison48).

An important factor affecting breast-feeding is marketing by the infant food industry(Reference Rothstein, Caulfield and Broaddus-Shea16,Reference Barennes, Empis and Quang40,Reference Grummer-Strawn, Holliday and Jungo49) . We observed the strong influence of the infant food industry through the widespread availability of formula and advertising, which has been shown to increase mothers’ interest in buying formula(Reference Putthakeo, Ali and Ito50,Reference Kaplan and Graff51) . Interestingly, in our study, mothers developed a liking to formulas they saw on television, consistent with formula companies’ marketing strategy to create brand preference(Reference Foss52). A UNICEF report on the violations of the WHO International Code of Commercialization of Breast Milk Substitutes (The Code) in Mexico indicated that over 50 % of mothers received recommendations from healthcare providers to feed their baby with dairy products and 80 % saw advertising about breast milk substitutes in the previous 6 months(Reference García Flores, Herrera Maldonado and Martínez Peñafiel53). Furthermore, infant feeding companies visited 15·5 % of private practices, reaching up to six communications per healthcare provider during the previous 6 months in 22 % of those cases(Reference García Flores, Herrera Maldonado and Martínez Peñafiel53). Such violations to The Code have been documented elsewhere in Latin America. In Peru, visits by formula representatives to healthcare providers are common and mothers often report receiving free formula and vouchers and even purchasing formula samples at discounted prices during their health visits(Reference Rothstein, Caulfield and Broaddus-Shea16). Studies have shown that providing nursing mothers with formula samples in hospitals can lead mothers to question the benefits of breast-feeding and doubt their own ability to breastfeed(Reference Rosenberg, Eastham and Kasehagen54–Reference Parry, Taylor and Hall-Dardess57). About 60 % of paediatric associations receive some form of financial support from the infant food industry, and this increases up to 82 % in the Americans(Reference Grummer-Strawn, Holliday and Jungo49). This is worrisome since research shows that doctors experience loyalty towards companies and feel obligated to prescribe their products(Reference Fabbri, Gregoraci and Tedesco58,Reference Rothman, McDonald and Berkowitz59) .

Several participants expressed that physicians recommended particular brands of formula, justifying the indication that breast milk was no longer sufficient or that babies were not gaining enough weight. A previous study found that mothers who received formula recommendations from healthcare providers were almost 10 times more likely to feed a mixed diet and up to four times more likely to abandon breast-feeding (Reference Rothstein, Caulfield and Broaddus-Shea16). In contrast, healthcare providers’ support for breast-feeding has been associated with increased odds of initiating and continuing breast-feeding(Reference Arora, McJunkin and Wehrer60,Reference Taveras, Li and Grummer-Strawn61) . Lu and colleagues found that when healthcare providers recommended breast-feeding, women were over four times more likely to initiate breast-feeding(Reference Lu, Lange and Slusser62). Combining the influence of the infant food industry on healthcare providers, lack of breast-feeding training and education, time constraints impeding adequate breast-feeding counselling, lack of social programmes offering breast-feeding counselling and the increase in obstetric practices that hinder breast-feeding (i.e. C-sections), we can understand how formula has now also become a social norm in highly socio-economically vulnerable communities.

Communication between healthcare providers and patients is not always adequate, leading to additional obstacles to breast-feeding, as was seen in this study(Reference Bueno-Gutierrez and Chantry63). In Peru, mothers have reported that nurses often only tell them to breastfeed but without providing specific instructions, and they have described their clinical encounters as impatient and disrespectful(Reference Rothstein, Caulfield and Broaddus-Shea16). When interviewed, the nursing staff acknowledged that time constraints and resource limitations deterred appropriate breast-feeding counselling(Reference Rothstein, Caulfield and Broaddus-Shea16). Another important aspect little studied in Latin America is racism and classism within health services. Previous studies have documented forms of institutionalised racism and discrimination towards vulnerable mothers in the context of infant feeding, as healthcare providers showed apathy towards those mothers and considered them as ‘too submissive’ to family influences, especially those of grandmothers(Reference Rodríguez and González12,Reference Schmied, Olley and Burns39,Reference Grewal, Bhagat and Balneaves64–Reference Puthussery, Twamley and Harding66) .

One interesting finding was the use of traditional beverages that carry symbolic meaning. For people unfamiliar with Mesoamerican culture, it may be surprising that infants can be given pulque. However, this derivative of the maguey, as well as foods derived from corn, is strong cultural and social traditions. The replacement of such traditional foods with infant formula identified in our study was similar to a study in Laos, which found that while mothers traditionally introduced rice to infants early on, they had begun to instead use breast milk substitutes as they believed these had similar nutritional value to rice(Reference Barennes, Empis and Quang40). It would be interesting to inquire whether traditional infant feeding practices, such as giving pulque or atole to infants in Mexico, are based on beliefs that these foods complement infants’ nutrition and if now formula is replacing those traditional foods. Beliefs that breast milk alone is insufficient may be influenced by the social and economic changes that communities experience, perhaps in response to strong infant food industry marketing. Formula advertising can represent formula as an option equal or complementary to breast milk, influencing infant feeding normative behaviours and social norms(Reference Piwoz and Huffman15). Murray has argued that we must scrutinise the origin of ideas that breast milk is insufficient and analyse if these beliefs are related to the claim that reproductive bodies are insufficient and need better management(Reference de López67).

The results of our study have implications for future interventions to support mothers who wish to breastfeed in these indigenous communities in Mexico. Counselling mothers, family members and healthcare providers may be beneficial in addressing the various misconceptions about breast-feeding. For example, providing mothers with anticipatory guidance based on key messages regarding the addition of teas, water and probaditas in the first 6 months of life may help improve the rates of exclusive breast-feeding. Key messages targeting the ideas that breast milk becomes unsuitable for the infant over time may help extend the overall duration of breast-feeding. Breast-feeding counselling must also be given for women to learn to overcome lactation problems that mothers commonly face, such as breast pain, perception of insufficient milk and beliefs that their baby is dissatisfied. To maximise their effectiveness, these interventions should include family members – particularly grandmothers – as these communities still have strong and deep cultural traditions. Future interventions will need to be respectful of such traditions and should be co-designed with the participation of community members for them to be successful and sustainable. Furthermore, training for healthcare providers must focus on standardising basic and applied breast-feeding pre-service and in-service training and education that includes improving communication skills that emphasise respect, dignity, humility and compassion.

Our study had several limitations. First, the external validity of our findings needs to be interpreted with caution as participants from our purposive sample were mostly low-income homemakers from indigenous communities in Central Mexico. In addition, most of our findings were based on self-reported behaviour and were dependent upon the participants’ recollections, associated feelings, and their recall may have been influenced by socially acceptable behaviours. Last, we were not able to return to the communities for validation and feedback of our results.

Conclusion

Our study offers new insights into the social ecology of infant formula in rural and indigenous communities in Central Mexico. Our findings are consistent with previous studies that demonstrated an epidemiological and nutritional transition in rural populations, but that had not been able to connect the dots as we did in the context of a SEF. While breast-feeding was still widely accepted so is infant formula nowadays. It is urgent to design multi-level and multisectoral interventions to prevent the further dissemination and revert the already strong infant formula culture that has formed in these highly vulnerable communities. Marketing regulation policies that are consistent with The Code need to be well enforced in order to protect the right that women have to breastfeed their children for as long as recommended.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: We thank all the families and healthcare providers who took their time to participate in this study and share their experiences with us. We are very grateful for the entire UKA staff who provided transportation and guidance throughout our data collection. This project would not have been possible without the help and support from everyone. Financial support: P.L. received funding for this project from the Yale School of Public Health Downs International Health Student Travel Fellowship and from the Yale School of Medicine Summer Research Fellowship. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: P.L., D.B.G., R.P.E. and A.G.M. conceived and designed the study. P.L., D.B.G., T.V. and B.G. enrolled participants and collected data. P.L., D.B.G., A.Z.A. and G.M.L. analysed the data. P.L. and D.B.G. wrote the manuscript. All authors participated to the writing of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving study participants were approved by the Yale Human Subjects Committee. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Verbal consent was witnessed and formally recorded.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021002433