Early childhood growth and development are established predictors of developmental and health outcomes throughout life and may influence the health and well-being of the next generation(1). Specifically, adverse exposures such as malnutrition during critical periods of developmental plasticity (first 1000 d; i.e., pregnancy and the first 2 years of life) are associated with sub-optimal growth, adiposity and developmental delays in childhood, as well as with obesity and non-communicable disease risk in later life(Reference Black, Victora and Walker2). This is particularly relevant in low- and middle-income countries such as South Africa, where both stunting and overweight/obesity affect approximately a quarter of children under the age of 5(Reference Shisana, Labadarios and Rehle3,4) . Within the framework of nurturing care, both adequate nutrition and responsive parenting approaches in early life are critical to building a foundation for optimal growth and development through infancy and childhood(1).

The WHO recommends exclusive breast-feeding for the first 6 months of life, with sustained breast-feeding up to 2 years of age, alongside the introduction of diverse, micronutrient-rich complementary foods in order to support optimal infant growth and development(1). These guidelines should be complemented by responsive caregiving approaches, which involve prompt and appropriate mother/caregiver–child interactions that promote the development of healthy appetites and eating behaviours(1). However, while guidelines for optimal infant feeding practices exist, global research shows that they are rarely achieved due to barriers such as conflicting sources of information and advice, financial constraints, convenience, misinterpretation of infant behavioural cues and lack of support and/or perceived pressure from healthcare workers, family members and friends(Reference Matvienko-Sikar, Kelly and Sinnott5–Reference Shortt, McGorrian and Kelleher8).

In South Africa, infant feeding guidelines and their interpretation have been strongly influenced by changes in guidelines for the Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV(9). Specifically, previous guidelines provided HIV-positive women with a choice to either exclusively breastfeed or to exclusively formula feed their infants, with free infant formula also being provided to HIV-positive women in healthcare facilities. However, in 2011, the Tshwane Declaration of Support for Breastfeeding in South Africa was introduced and aimed to promote exclusive breast-feeding to all women, regardless of their HIV status, leading to a shift in the advice given to HIV-positive women, as well as an end to free infant formula provision(10). While policy changes reflect WHO recommendations, poor communication around these changes between policy makers, healthcare providers and mothers, as well as the stigmatisation of HIV and its established link to infant feeding practices in South African communities, continues to influence maternal decision making(Reference Nieuwoudt, Manderson and Norris11,Reference Nieuwoudt and Manderson12) .

Quantitative and qualitative research conducted in South Africa has shown that, although the initiation of breast-feeding has greatly increased since 2011 (>90 %), only 32 % of infants under 6 months of age are exclusively breastfed and mixed feeding is common – with non-breast milk liquids and solids often introduced before 2 months of age(4,Reference Nieuwoudt, Manderson and Norris11–Reference Mushaphi, Mahopo and Nesamvuni13) . Potential explanations for this have been an ongoing prominence of exclusive breast-feeding education and advice around HIV (rather than infant health) and a lack of emphasis on the risks of mixed feeding(Reference Nieuwoudt, Manderson and Norris11). While useful for understanding the context surrounding early infant feeding practices and exclusive breast-feeding rates, the focus of the literature fails to elucidate the wider context of feeding practices across the early infant period. In addition, in settings such as South Africa where approximately 14·3 million are defined as vulnerable to hunger, food insecurity and a lack of access to high quality, micronutrient-rich foods may restrict the ability of caregivers to provide adequate diets to their infants(Reference Chakona and Shackleton14). Further exploration into infant feeding practices in South Africa across the first 2 years of life – particularly related to the quality and diversity of complementary foods and their introduction – as well as what influences maternal feeding practices overall therefore requires further investigation.

This qualitative study used focus group discussions (FGD) and in-depth interviews (IDI) with mothers of infants aged 0–24 months to (i) describe the infant feeding practices of urban South African women living in Soweto and (ii) understand from the mothers’ perspective what influences these feeding practices.

Methods

Participants

Study participants were recruited from an existing study (the International Atomic Energy Agency multicentre infant body composition study) taking place at the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC)/Wits Developmental Pathways for Health Research Unit (DPHRU) at Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital in Soweto, Johannesburg, South Africa. The International Atomic Energy Agency study recruited two cohorts of mother–infant pairs from the maternity ward at Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital and followed them up from either birth to 6 months (n 250) or three- to 24 months (n 400) in order to (i) develop references for infant body composition and (ii) assess factors associated with changes in body composition during infancy. Mothers involved in the current study consented to be contacted for future studies, and this platform was therefore used to identify mothers with infants across a range of infant ages (0–24 months). In order to achieve a desired sample size of six to eight mothers per FGD, a total of twenty-eight mothers were randomly selected and invited to participate, with nineteen agreeing to take part in one of three FGD at the DPHRU site.

Data collection

FGD were arranged by the age of the mother’s baby as follows: one each for mothers of 0–6-month-olds, 7–14-month-olds and 15–24-month-olds. From those included in the FGD, twelve mothers were selected for inclusion in the individual IDI – with an even split according to the FGD that they attended. The four IDI per age group were observed to reach data saturation across all dimensions identified during the exploratory FGD phase. Prior to commencement of the FGD, all mothers completed a short questionnaire with a trained member of research staff which covered basic socio-demographic information. Both the FGD and IDI began in English – with flexibility to use vernacular languages – and were audio recorded. The FGD and IDI were all conducted by a qualitatively trained facilitator at the DPHRU site, while comprehensive field notes were compiled by an observer to supplement the audio files. Both the facilitator and the observer were fluent in the vernacular languages used. The focus group sessions lasted between 60 and 120 min each, and the interviews lasted between 60 and 90 min each. All participants were reimbursed for their transport costs and received refreshments when attending the FGD and IDI.

While a semi-structured guide was used to facilitate the FGD (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Appendix 1), the facilitator encouraged interaction and discussion between participants, as well as brainstorming of topics around their baby’s health and well-being, movement, development and their feeding practices. This allowed for an exploratory approach to the group discussions, rather than promoting a didactic nature of posing formal questions. In addition, while the FGD were aimed at discussion of mothers’ experiences with the children included in the study (i.e. within the age range of the FGD they were involved in), the open-ended nature of the FGD meant that mothers may have discussed experiences with previously born children if relevant to the conversation. Emerging themes from the FGD were then used to develop and refine the IDI guide (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Appendix 2), which was designed to provide a deeper understanding of the topics discussed during the FGD, as well as explore any gaps identified during FGD analyses. However, this interview guide remained semi-structured in order to promote open discussion and to allow for exploration into the approaches and perceptions described by mothers. After completion of the FGD and IDI, the audio files were transcribed verbatim by an external transcriber fluent in both English and the vernacular languages used. Where vernacular languages were used during the discussions, the transcriber subsequently translated the transcription to English. In order to verify accuracy, all transcripts were thoroughly checked against the recordings by either the original facilitator or observer of the FGD or IDI.

Data analysis

The three FGD transcripts were divided between three researchers who read and re-read their allocated transcript to familiarise themselves with the content. Researchers used a combination of deductive (pre-identified themes based on the research question) and inductive (emerging themes from the transcripts and field notes) approaches to identify and analyse themes. After initial identification of themes, researchers swapped transcripts and coding frameworks to cross-check interpretation and theme identification across the group. Individual-level reviews were followed by group meetings to compare, contrast and discuss emerging themes, while incorporating the principles of the immersion-crystallisation method(Reference Borkan, Crabtree and Miller15). An independent researcher tested reliability and internal validity of the data coded from the FGD and, where differences were established, reported these to the team. Discrepancies were then discussed and resolved as a group to ensure that codes and text reflected the definitions generated by the team. The independent researcher then cross-checked and collated common and unique themes across the three transcripts to develop an overall data codebook for the three FGD. Following coding, a group meeting was held to complete data analysis and interpretation of themes, and the codebook was interrogated and refined until no new themes emerged.

The codebook developed during FGD analysis was used as a basis for coding the IDI. The team of four researchers independently used the FGD codebook to analyse all twelve IDI according to four primary research areas identified from previous research and confirmed or refined based on the emerging themes from the FGD, namely (i) infant caregiving and well-being; (ii) infant feeding practices; (iii) infant movement, play and development and (iv) perceptions around infant body size. Due to the complexity of the individual research areas, these were analysed and interpreted separately, with infant feeding practices being the area of focus in this case. Where the FGD codebook did not include sufficiently detailed themes for a particular research area (i.e. infant feeding), further themes were identified and added. After coding and theme identification had been completed, a process of cross-cutting theme identification and confirmation across FGD and IDI was carried out. Once this process had been finalised per research area, the combined themes and subthemes for the FGD and IDI were shared between the research team members for interrogation of the identified themes, and these were refined and agreed upon as a group. For the purpose of the current study, only the themes and sub-themes related to infant feeding practices are presented. In order to illustrate the themes that emerged from the FGD and IDI, exemplar quotations were excerpted.

Results

The characteristics of mother–infant pairs included in the study are summarised in Table 1. The mean ages of mothers per FGD were as follows: FGD1 (n 6), 26 (sd 4) years; FGD2 (n 7), 26 (sd 4·5) years; and FGD3 (n 6), 28 (sd 5·5) years. All mothers had attended secondary school and the majority were unemployed (n 14). Only one mother was married and lived with the baby’s father. The majority of the infants were male (n 12), and the mean ages of the babies per FGD were FGD1, 4 (sd 2) months; FGD2, 9 (sd 4) months and FGD3, 19 (sd 2·5) months.

Table 1 Characteristics of mother–infant pairs according to focus group discussion (FGD) attendance

The results of the study are separated according to the two study objectives, namely (i) contextual information provided by mothers about their infant feeding practices – focusing on what and how babies were being fed in Soweto and (ii) emerging themes describing maternal perspectives on what influences infant feeding practices in Soweto.

Infant feeding practices

What babies are fed

All mothers described initiating breast-feeding with their baby; however, the majority had not breastfed exclusively for any length of time. Instead, mothers introduced solid foods as early as the first or second month of life, alongside breast milk and/or formula. The first food introduced was commonly a soft maize porridge called ‘cream of maize’, which is a commercially purchased and fortified porridge designed as a weaning food from 6 months of age. Some mothers also gave a soft, sorghum-based porridge (known as ‘Mabele’) which, depending on the brand or whether it was specifically designed for weaning, may, or may not, have been fortified. For younger babies, porridge was often made very watery so that it could be fed from a bottle. Tea (usually decaffeinated rooibos) and water were also given to babies from a very young age.

As babies got older (around 5 or 6 months of age), other solid food was introduced. Common food items included commercially prepared baby foods, other cereals such as Weet-bix, bread, other maize-based porridge (pap or samp), sour milk (maas) and yogurt. Mothers with older infants discussed continuing to breastfeed and/or give infant formula past the baby’s first birthday.

In general, mothers had a perception that their babies did not like vegetables and/or fruit and therefore these were rarely fed to babies up to 2 years of age. However, some mothers did feed their babies vegetables, and these were mostly starchy vegetables like pumpkin and potato. Some mothers also gave vegetables such as carrots, cabbage, spinach and beetroot to their babies when they were being cooked for the family. Specifically, at night, most babies were fed maize porridge with gravy or maas. Some were given small amounts of meat or vegetables from the family meal, but most were fed only the gravy from the family food pot.

Many mothers gave their babies ‘junk’ food as a snack and believed that all children liked and needed small amounts of these foods. Common snacks included crisps, sweets and lollipops, biscuits and juice, as well as other sugar-sweetened fizzy drinks. However, in some cases, yogurt (usually flavoured, sweetened yogurt) and fruit (apple and banana) were given to babies as snacks in an attempt to avoid ‘junk food’.

How babies are fed

Most mothers fed their babies from their own plates or bowls, rather than from a shared plate. Young infants were commonly fed off the mother’s lap using a bottle or spoon, with food often being mashed to allow them to eat it easily. Some mothers allowed their babies to begin feeding themselves once they were old enough to express a desire to do so. However, others did not allow this, as they felt their babies would play with their food rather than eat it. Babies that refused to eat were often force-fed.

Many babies in Soweto were fed ‘in their own time’ at home, rather than while the mother/family was eating. However, some ate together with the family during the evening meal. As many of the mothers did not have a separate dining area in their homes, feeding tended to occur where it was convenient at the time – either in the main room of the home or in the kitchen. Some mothers described feeding their babies or allowing them to eat in front of the television.

Mothers perceived fussiness and crying (or fake crying) as the most common hunger cue for babies; however, as they got older, children would tell their mothers when they were hungry or would seek out food themselves. Common cues of fullness were babies closing their mouths, spitting out their food or moving their heads away. As babies got older, they would begin playing with their food when they had eaten enough or they would tell their mothers they were full once able to vocalise this.

What influences infant feeding practices

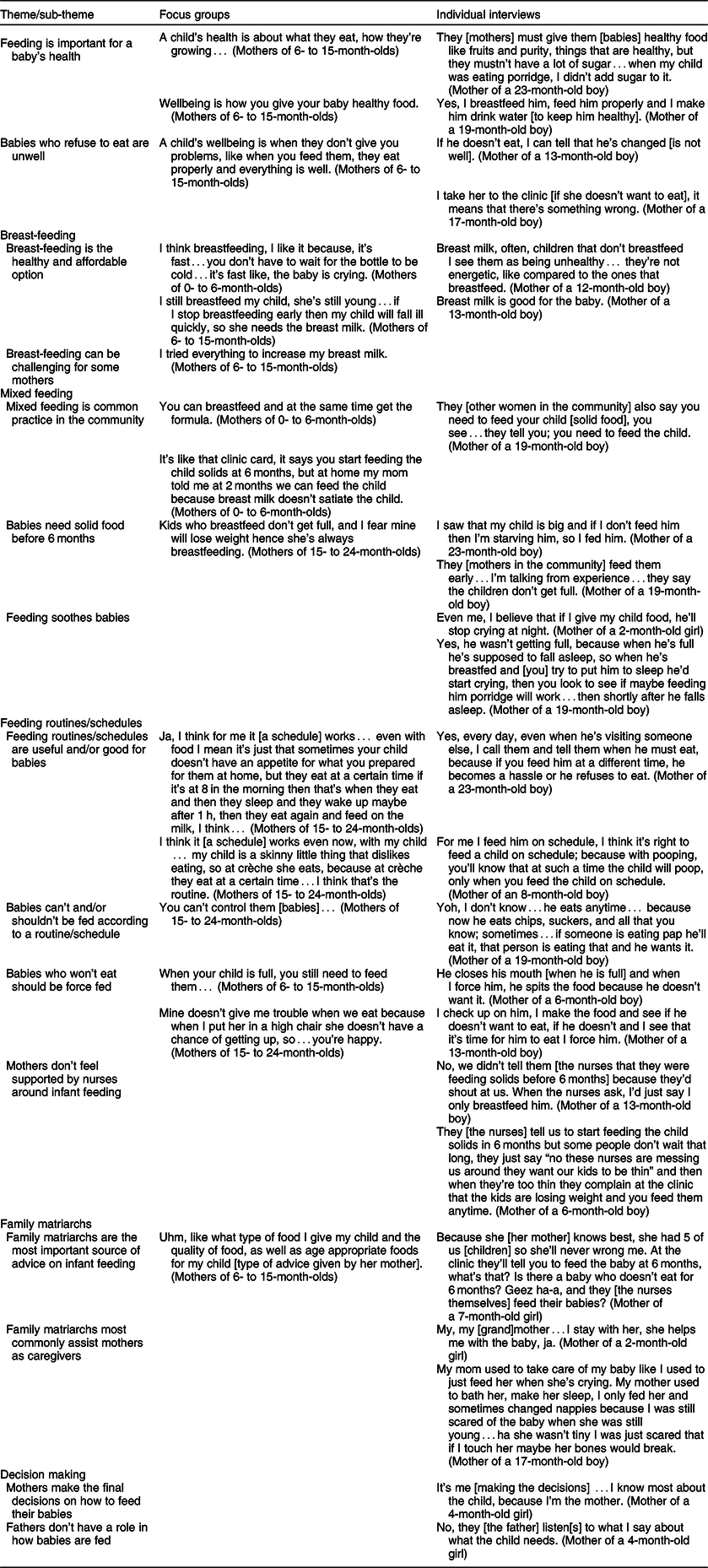

The factors that mothers felt influenced their infant feeding practices were identified according to ten main themes, as presented below. A complete description of the themes and sub-themes, as well as additional exemplar quotations, is provided in Table 2.

Table 2 Emerging themes, sub-themes and exemplar quotations related to mothers’ perceptions of what influences infant feeding practices in Soweto, South Africa

Feeding is important for a baby’s health

Across the study, mothers described an understanding that how and what babies ate was important for their health. They believed that healthy babies eat well and that feeding their babies healthy food (including breast milk), and avoiding sugary food in some cases, was a key part of keeping them healthy:

[A healthy child is] a child that is well taken care of and well fed… he eats a lot, eats well. (IDI; mother of a 1-month-old boy)

Babies who refuse to eat are unwell

Similarly, mothers perceived a lack of appetite or an unwillingness to eat as a sign of ill health:

To be able to make sure your child is eating and if they’re not then to be aware that they’re not and why they’re not… to understand if they don’t eat, then they’re sick. (FGD; mothers of 15- to 24-month-olds)

Breast-feeding

Breast-feeding was determined to be the healthy and affordable option for infant feeding. Mothers specifically described breast-feeding as ‘good’ or ‘healthy’ for the baby across the study, with those in the FGD also perceiving it to be the convenient and affordable option:

I think breastfeeding is the most affordable and healthiest thing to consider for the baby. (FGD; mothers of 0- to 6-month-olds)

If you breastfeed your baby, she’ll become healthier than one who drinks Nan [formula milk]. (IDI; mother of a 17-month-old boy)

However, during the FGD, mothers also acknowledged that breast-feeding can be challenging for some mothers. They described experiences (either personally or from the community) of mothers being unable to produce enough milk for their babies, as well as difficulties in being able to breastfeed babies in public places or once they returned to work:

Some ladies, they want to breastfeed but they have no milk in their breasts, others want to breastfeed but maybe they’re at work. (FGD; mothers of 0- to 6-month-olds)

Some people get sick when they see you taking out your breast, they say “sies, why you don’t buy your child a bottle or something” …like more in public places…they don’t like it. (FGD; mothers of 0- to 6-month-olds)

Mixed feeding

Particularly during IDI, women discussed that mixed feeding is common practice in the community, with many mothers combining breast-feeding with formula and/or other liquids and solids from an early age:

At home there were people using the bottle, but also breastfeeding. (IDI; Mother of a 4-month-old girl)

When I started, I used to feed him formula and breast milk, and then from 4 months I started giving him Nestum, and cream of maize, and ProNutro… (IDI; mother of a 6-month-old boy)

Mothers described their mixed feeding practices – and the early introduction of solid food in particular – being influenced by a belief that babies need solid food before 6 months. Specifically, there was a strong perception that if their babies were only fed milk for 6 months that they would not feel full and may lose weight:

Anyway, we do feed our children solids because milk doesn’t make them full. (FGD; mothers of 15- to 24-month-olds)

If my child was 6 months without eating solids, he’d be skin and bones only not chubby as he is now. (FGD; mothers of 0- to 6-month-olds)

Feeding soothes babies

Infant feeding and weaning practices were also influenced by the baby’s behaviour, with mothers expressing an understanding that feeding their babies would stop them from being fussy or crying. To an extent, mothers saw feeding as a way of soothing a ‘problematic’ baby and also believed that feeding would promote sleep:

They give us problems, they just cry and cry, but if you feed them, they are alright, they don’t bother you and cry incessantly. (IDI; mother of a 4-month-old girl)

Feeding routines/schedules

Mothers expressed contrasting feelings around the idea of feeding babies according to a routine/schedule. Specifically, some mothers thought that feeding routines/schedules were useful and/or good for babies, either making babies less of a ‘hassle’ or ensuring that they grew properly:

They say that when you feed them at the right time [they will be normal body weight], maybe in the morning something and then in the afternoon something different and then later as well something different. (IDI; mother of a 4-month-old girl)

In contrast, some mothers felt that babies cannot and/or should not be fed according to a routine/schedule, believing that babies eat when they are hungry and you cannot ‘control’ them. Feeding routines/schedules were also perceived as too restrictive in some cases – with some mothers believing that they would prevent their baby from being able to adapt to change:

My child needs to eat at different times so that she gets used to change, like my child will eat porridge and then if you give her a banana she’ll eat it and if you give her water she’ll take it, so she doesn’t have a time schedule, she eats anytime. (FGD; mothers of 6- to 15-month-olds)

My child doesn’t have a schedule for eating; she eats when she’s hungry. (FGD; mothers of 6- to 15-month-olds)

Babies who will not eat should be force fed

Across the study, mothers discussed believing that babies should be force-fed when they refused to eat:

I force him [when he won’t eat] then he spits it out…I pick him up, squeeze him and feed him [using her hand]. (IDI; mother of a 19-month-old boy)

In addition, while use of high chairs was rare, a couple of mothers in the FGD described using these as a tool to force their children to eat, thereby limiting their ability to move around and avoid eating:

Because when I put her under my arm, when I feed her once she tries to get up…so when I feel that she’s giving me too many problems I put her in the high chair, I know in the high chair she doesn’t go forward and she doesn’t go back. (FGD; mothers of 15- to 24-month-olds)

Family matriarchs

Throughout the study, mothers explained that family matriarchs are the most important source of advice on infant feeding in Soweto. In particular, their own mothers and grandmothers routinely promoted mixed feeding, and mothers reported experiencing a lot of pressure from maternal figures to introduce solids before 6 months of age:

They also say you need to feed your child, you see, especially the older ones, the grannies, those are the ones I take most of the advice [from]… (IDI; mother of a 19-month-old boy)

In addition, as the advice provided by family matriarchs often conflicted with that received at health facilities, women often prioritised the advice from their babies’ grandmothers and great-grandmothers above that of health professionals. This was commonly influenced by the fact that they either trusted in the experience of their mothers and grandmothers or they felt pressured to follow this advice within the home environment where they lived with, and received support from, these matriarchs:

We have parents [mothers, grandmothers] that guide us through their experience of raising us, I believe they know what’s good for our kids. (FGD; mothers of 6- to 15-month-olds)

Yoh, I don’t know…because I’m scared of my grandmother, she’s helping me and she’s like you have a baby, I was there when you were a baby…like “I raised you” …I stay with her, and at night she’s there; so if I don’t listen to her when she says I must feed the baby, and like maybe if like the child is crying, she won’t take that child, she’ll be like, ‘I told you that you must feed that baby, I told you…’’ (IDI; mother of a 2-month-old girl)

Women who attended the IDI also explained that, in their community, as well as being the primary source of information and advice around infant feeding, family matriarchs most commonly assisted mothers as caregivers. As these women took care of their babies when the mothers needed support, they were often highly influential in the feeding methods adopted – routinely carrying out these practices in the home environment:

By then I didn’t know anything; so, she [her mother] helped me, she looked after them [her children]; she was always by my side. (IDI; mother of a 19-month-old boy)

Mothers do not feel supported by nurses around infant feeding

The majority of mothers expressed a lack of support from nurses around the feeding practices they adopted, leading to a lack of trust and honesty between nurses and mothers. Nurses strongly emphasised the need to exclusively breastfeed until 6 months of age and mothers expressed feeling pressured to do so when attending health facilities. However, as the information and advice given to them by nurses often contradicted that of their babies’ grandmothers and great-grandmothers, it was common for mothers to lie to health professionals about how they were feeding their babies in an effort to avoid judgement – or even to avoid being shouted at or threatened by nurses during clinic visits:

No, like I can’t say that, yoh, this nurse will be like, “I told you to do this [exclusively breastfeed] and you do this…” like now the whole clinic is looking at me, yoh…Ja, she’ll make noise, no…Ja, ja I don’t want to be judged. (IDI; mother of a 2-month-old girl)

They [other mothers] won’t say [that they are feeding their babies solids before 6 months], they won’t, they’re scared; and the nursing sisters tell you that if you feed the child solids before they’re 6 months old and it harms the child, we’re going to have you arrested, we won’t take it lightly, so how can you tell the truth…you just keep quiet and tell them you didn’t feed the child. (IDI; mother of a 6-month-old boy)

Decision making

Regardless of the advice that was received around infant feeding, some women expressed a strong feeling that mothers make the final decisions on how to feed their babies:

Me [makes the decisions] …yes, they have an input but if I don’t agree with them, I still have the final say. (IDI; mother of an 8-month-old boy)

In addition, the view that fathers do not have a role in how babies are fed was expressed. Women therefore felt that there was no difference in how babies were fed if their fathers were present or not:

Uh, no…as the mother you can do most of the things, you don’t need [the father]. (IDI; mother of a 1-month-old boy)

However, there was some acknowledgement during IDI that fathers could provide financial support if they were involved in the lives of mom and baby which would be beneficial in providing for the baby’s needs:

It would be different [if I lived with my partner] because even his support we would receive, rather than being alone and not working…financially, I’m just not able to make ends meet, because I have no income, I’m raising him on grant money, so if he was there, supportive and giving us money, I’d be able to give the child some of the things he needs. (IDI; mother of a 12-month-old boy)

Discussion

This qualitative study aimed to describe the infant feeding practices of mothers living in Soweto, South Africa, and to explore their perspectives on what influences these. Our findings showed that, while mothers understood that breast-feeding was beneficial, the duration of exclusive breast-feeding was very short. The diversity and quality of weaning foods was low and ‘junk’ food was commonly given. Babies were routinely fed using bottles or spoons and this often happened separately to family meal times.

Feeding practices in Soweto were strongly influenced by a belief in the importance of feeding for health, with an unwillingness to eat being a sign of ill health. As such, it was common for mothers to force-feed their babies. Mothers also believed that feeding solid food was necessary to soothe babies. Feeding practices were highly influenced by family matriarchs, and mothers did not believe that fathers had a role in making feeding decisions. Mothers did not feel supported by nurses and therefore tended to lie about their feeding methods at health facilities.

Mixed feeding and the early introduction of solid foods

Exclusive breast-feeding has been a focus of infant feeding literature in South Africa and, although some improvement has been demonstrated, exclusive breast-feeding to 6 months remains rare(Reference Siziba, Jerling and Hanekom16,Reference Nieuwoudt, Ngandu and Manderson17) . Continually low exclusive breast-feeding rates have, to an extent, been attributed to the historical focus on breast-feeding exclusivity for HIV-positive women and therefore the stigma that remains between exclusive breast-feeding and non-voluntary HIV disclosure(Reference Nieuwoudt, Manderson and Norris11). Additionally, poor communication and training of health workers around policy changes have resulted in a lack of understanding of the importance of breast-feeding for infant health and development overall, as well as of the dangers of mixed feeding(Reference Nieuwoudt and Manderson12,Reference Martin-Wiesner18) . Without adequate training and investment in the guidelines that they promote, health workers tend to provide dogged emphasis on exclusive breast-feeding, seemingly removing any choice from mothers and making open discussion and support around infant feeding impossible(Reference Nieuwoudt and Manderson12). As demonstrated in our study, a lack of support from nurses around infant feeding behaviours can lead to distrust and dishonesty between mothers and nurses. If exclusive breast-feeding interventions are to be successful, equipping health workers to educate and support mothers in an open and compassionate way is essential to facilitating greater maternal self-efficacy around exclusive breast-feeding.

The importance of an effective health workforce has been recognised as a priority in South African literature and is acknowledged globally as a part of WHO’s Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative which has, in part, been responsible for positive trajectories in exclusive breastfeeding rates in middle-income settings such as Brazil(Reference Nieuwoudt, Ngandu and Manderson17,Reference Rollins, Bhandari and Hajeebhoy19,20) . While the principles behind Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative are committed to by South Africa in our own Mother-Baby Friendly Initiative, substantial inequalities and disparities in implementation continue to isolate the most vulnerable mothers and babies(Reference Martin-Wiesner18,Reference Gray, Vawda, Padarath, King and Mackie21) . In addition, while this intervention may successfully promote breast-feeding initiation, mothers face numerous barriers to sustained breast-feeding within their community and home environments that require ongoing promotion and support. Addressing these inequalities in the health system and its support structures – particularly in low-income areas and at community level – should be prioritised by government if the efficacy is to be improved and sustained.

As seen in our study, complex and interrelated factors influence whether or not a mother sustains exclusive breast-feeding, with perceived breast milk insufficiency and the inadequacy of milk alone, the use of food to soothe, the involvement of other caregivers and the pressure felt from family and/or community members all contributing to the cessation of exclusive breast-feeding(Reference Mushaphi, Mahopo and Nesamvuni13,Reference Nieuwoudt, Ngandu and Manderson17,Reference Gray, Vawda, Padarath, King and Mackie21,Reference Jama, Wilford and Masango22) . Nieuwoudt et al. (Reference Nieuwoudt, Ngandu and Manderson17) recently showed that combined and complementary interventions at the individual, family, community and health facility levels are necessary to break the contextual barriers and norms surrounding exclusive breast-feeding in South Africa and promote breast-feeding self-efficacy in mothers.

In the Lancet’s breast-feeding series, Rollins et al. (Reference Rollins, Bhandari and Hajeebhoy19) demonstrated that, across low- and middle-income countries, adequate implementation of concurrent interventions across channels can facilitate substantial improvement in breast-feeding rates, with combined health system and community-based interventions shown to increase breast-feeding exclusivity by 2·5 times. As highlighted by our study, community norms around mixed feeding and the strong influence of family members – and matriarchal figures in particular – should be targeted to promote appropriate infant feeding guidance and support. The development of well-trained peer support networks, for example, has been shown to successfully increase exclusive breast-feeding rates to 6 months of age in countries such as India, Bangladesh and the Philippines, with the frequency of contact between mothers and peer counsellors being associated with greater improvement(Reference Shakya, Kunieda and Koyama23). The Grandmother Project – a non-profit organisation working to improve the health and well-being of women and children in low- and middle-income countries such as Senegal – also provides useful methodology, specifically using a ‘Change through Culture’ approach to utilise the role of grandmothers in their communities for the improved health and well-being of women and children(Reference Aubel24). This approach has been effective in strengthening the knowledge and advocacy of grandmothers around nutritional health and promoting timely and improved complementary feeding. Additionally, in Brazil, mass media campaigns and social mobilisation, alongside investment in human milk banks and policies around kangaroo-mother care, have contributed to improvements in exclusive breast-feeding and should be explored in this setting(Reference Rollins, Bhandari and Hajeebhoy19,Reference Santos, Barros and Horta25) .

Weaning and complementary foods

While the early introduction of solid food has been explored in the literature, the diversity and quality of the complementary foods introduced during early life have received less attention, particularly with qualitative approaches and in African settings(Reference Robinson26,Reference Sayed and Schönfeldt27) . However, as in our study, data indicate that maize porridge and commercially produced infant cereals are most commonly given to South African infants, alongside liquids such as water and tea below 6 months of age(Reference Sayed and Schönfeldt27,Reference Mamabolo, Alberts and Mbenyane28) . In addition, porridge is often diluted to produce a thin and/or soft consistency that facilitates easier feeding, thus lowering the nutrient density per serving(Reference Sayed and Schönfeldt27). Use of grain-based ‘gruel’ and starchy staples as predominant food sources during the first 6–23 months of life is associated with poor growth in early childhood(Reference Steyn, Nel and Nantel29,Reference Udoh and Amodu30) .

The limited variety and quality of complementary foods given to babies in our study may, in part, be driven by a lack of dietary quality and diversity in the home. However, mothers’ perceptions that their babies did not like certain foods (particularly vegetables) were also described to influence the weaning foods provided. As mothers associated a baby’s willingness to eat and eating ‘well’ (i.e. eating enough) with their health and well-being, they were inclined to feed familiar and/or ‘junk’ foods that would be accepted and promote ‘fullness’ rather than novel foods that may be refused. In contexts such as Soweto, where food insecurity plagues households and regular access to high-quality, healthy food may be limited, mothers may also be reluctant to offer novel food items to infants due to the risk of refusal and, potentially, food waste(Reference Ntila, Siwela and Kolanisi31).

Data from high-income settings show that familiarisation of new tastes through repeated exposure to novel foods is important in encouraging acceptance of new foods into the diet(Reference Mura Paroche, Caton and Vereijken32,Reference Anzman-Frasca, Ventura and Ehrenberg33) . This is particularly important for bitter tastes, such as vegetables, which infants may refuse at the first exposure(Reference Hetherington, Schwartz and Madrelle34). Specifically, greater exposure to various vegetables during weaning has been associated with reduced food fussiness and higher, more preferential, vegetable consumption in childhood(Reference Maier-Nöth, Schaal and Leathwood35,Reference Mallan, Fildes and Magarey36) . In addition, establishment of a ‘junk’ food driven diet by the age of three has been associated with higher adiposity as children age(Reference Reilly, Armstrong and Dorosty37,Reference Leary, Lawlor and Davey Smith38) . This suggests that, particularly in increasingly obese settings such as Soweto, exposure to a variety of healthy foods, alongside minimal exposure to junk food items, during the weaning period may be important in shaping food preferences and establishing healthier trajectories of dietary intake. Therefore, interventions that encourage and support mothers (and other caregivers) towards timely and appropriate introduction of novel foods may be central to shifting emerging dietary preferences and patterns during the early years.

Feeding styles

In the era of increasing childhood obesity, there has been a growing focus on the promotion of responsive feeding which involves timely recognition and response by the caregiver to the infant’s hunger and satiety cues(Reference Hurley, Cross and Hughes39). This approach is associated with the development of appetite regulation in infants and is believed to promote healthier food relationships and reduce the risk of obesity across the life course(Reference Savage, Hohman and Marini40). Our study shows that mothers in Soweto have a tendency towards non-responsive feeding practices – including inappropriate responses to hunger and satiety cues, taking excess control over feeding ‘events’ and/or being inadequately engaged in positive feeding interactions(Reference Hurley, Cross and Hughes39,Reference Harbron and Booley41) . Such feeding behaviours during early life have been associated with the development of unhealthy food relationships and emotional eating behaviours, as well as the adoption of poor-quality diets(Reference Hurley, Cross and Hughes39). In addition, non-responsive feeding behaviours – such as consistent use of food to soothe – have been associated with more rapid weight gain between 6- and 18 months of age(Reference Hurley, Cross and Hughes39).

Responsive parenting interventions indicate that providing information and support to mothers can facilitate more reactive and appropriate responses(Reference Savage, Hohman and Marini40,Reference Daniels, Mallan and Nicholson42) . Specifically, guidance on contingent and developmentally appropriate feeding practices has been associated with more sensitive and structured feeding behaviours, as well as a reduction in pressured feeding styles and feeding to soothe(Reference Savage, Hohman and Marini40). Further, group-based anticipatory guidance with mothers has been shown to promote maternal self-efficacy and, therefore, more protective feeding behaviours and interactions(Reference Daniels, Mallan and Nicholson42). This suggests that targeting styles of feeding within communities like Soweto through education and support around responsive feeding practices may promote more reactive and developmentally appropriate feeding interactions, as well as the development of healthy appetites and eating behaviours.

While the South African Department of Health provides all mothers with a Road to Health booklet which is designed to educate women in five key pillars for optimal health, the nutrition-based content largely focuses on breast-feeding and types of weaning foods, with a lack of emphasis on responsive feeding styles and the importance of support structures around infant feeding within the community. This, in addition to the effective use of such resources at health facilities, as well as the implementation of complementary health promotion messaging, should be prioritised in future government interventions(Reference Wiles and Swingler43).

Engaging fathers in caregiving practices and support

As seen in our study, much of the caregiving support received by mothers in communities such as Soweto is from their own mothers and grandmothers, with fathers often being absent for a variety of social and economic reasons(Reference Meintjes, Hall and Sambu44,Reference van den Berg and Makusha45) . While the majority of mothers in our study were single, they did not necessarily see the absence of fathers as a challenge to caregiving (with the exception of potentially providing financial support). This is common across African settings where childcare and feeding practices are predominantly determined by cultural norms and primarily enforced by the mother (or grandmother/great-grandmother in some cases)(Reference Aubel46).

While it may not be the norm in communities such as Soweto, previous research shows that many mothers desire greater involvement and support from fathers around infant feeding(Reference Chintalapudi, Hamela and Mofolo47). In addition, research shows that involving fathers in feeding education may facilitate the adoption of a more supportive paternal role, particularly related to financial and emotional support, protection of the mother–baby dyad and encouragement to engage with health services(Reference Mgolozeli, Khoza and Shilubane48). As with family matriarchs, feeding information and support services should increasingly engage fathers where possible in order to establish optimal support structures for mom and baby. Through better engagement of all family members, we can therefore aim to reduce the isolation and uncertainty felt by individual parents and grandparents and establish a more cohesive and unified approach to infant feeding across households and communities.

Strengths and limitations

Our study presents a unique exploration into infant feeding practices during the first 2 years of life. Specifically, our findings provide novel information on the context of exclusive breast-feeding in South Africa and emphasise the complex and entrenched factors that reinforce the low likelihood of exclusive breast-feeding. In addition, by combining this with exploration into parenting styles and support structures in Soweto, we use two complementary qualitative approaches to provide a new dimension to understanding infant feeding overall.

However, the study was not without limitations. First, the FGD and IDI were conducted at our research site, and this limited our ability to validate whether what was discussed was really what happened in the community. However, through engagement with mothers of infants at a variety of ages and the use of rigorous data analysis strategies, we were able to depict major themes that were common across groups and individuals. Our study only involved mothers, rather than including other caregivers. Given the strong influence of other caregivers on infant feeding practices, future research should explore the perceived role of these individuals in supporting mothers around infant feeding, as well as how this may be enhanced to benefit infant health and development. As this was a qualitative study and only involved nineteen participants, our findings are not generalisable to the population of Soweto. However, as in all qualitative research, our objectives were exploratory in nature and therefore the three FGD and twelve IDI were effective in capturing experiences and perceptions of infant feeding behaviours and in reaching data saturation(Reference Hennink, Kaiser and Marconi49).

Conclusion

The study findings highlight three key elements that may be useful for intervention development. First, a mother’s confidence in her ability to exclusively breastfeed is critical and support to foster breast-feeding self-efficacy is much needed. Second, shifting the norms around mixed feeding and the early introduction of solid foods and promoting more responsive feeding approaches should play a central intervention role. Lastly, engaging family members – particularly grandmothers and great-grandmothers, as well as fathers where possible – is important in promoting more supportive household and community structures around infant feeding and empowering mothers to make healthier choices for their infants. Given the complex interplay of factors influencing the ability of individuals to make healthy lifestyle choices for themselves and their families, prioritising the establishment of healthy appetites and eating behaviours in the early years is central to optimising the health trajectories of current and future generations.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank the mothers who took part in the current research and the research teams whose work we represent here. Financial support: S.V.W., A.P. and S.A.N. are supported by the DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Human Development at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. S.V.W. is also supported by the University Research Office and School of Clinical Medicine at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. The research was supported by the South African Medical Research Council and Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: S.V.W. conceptualised and wrote the manuscript. A.P., W.S. and E.C. conceptualised and managed the study. S.V.W., A.P., W.S. and E.C. developed the focus group discussion and/or in-depth interview guides and analysed the data. S.A.N. was the main investigator of the project and acquired the funding. All authors were involved in interpretation of results and reviewed the manuscript. All authors gave final approval of the version to be submitted. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all research involving study participants was approved by the University of the Witwatersrand’s Research Ethics Committee (Medical; approval numbers M171129 and M170707). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020002451