Over the past decade, research has shown that family meals are protective against poor dietary intake( Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Hannan and Story 1 – Reference Utter, Scragg and Schaaf 5 ), unhealthy weight-related outcomes (e.g. excessive weight gain, disordered eating behaviours)( Reference Utter, Scragg and Schaaf 5 – Reference Berge, MacLehose and Loth 17 ), substance use( Reference Fulkerson, Story and Mellin 18 , Reference Eisenberg, Neumark-Sztainer and Fulkerson 19 ) and poor psychosocial outcomes in children, adolescents and young adults( Reference Fulkerson, Story and Mellin 18 , Reference Fulkerson, Strauss and Neumark-Sztainer 20 , Reference Eisenberg, Olson and Neumark-Sztainer 21 ). Researchers posit that eating together yields both physical and psychosocial benefits for youths and adults alike by offering a daily opportunity for healthful eating and connection between family members( Reference Berge, MacLehose and Loth 17 , Reference Flattum, Draxten and Horning 22 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Larson and Fulkerson 23 ). Given existing findings which strongly suggest that family meals can serve to protect youths from a number of harmful health-related outcomes, participation in regular family meals has been recommended by several prominent organizations, associations and researchers( 24 – Reference Dietz and Stern 28 ).

Unfortunately, despite numerous known health benefits and widespread public health messaging informing families of the importance of eating regular family meals, many families are not eating together; data suggest that the frequency of family meal consumption has decreased over time, particularly among low-income families( Reference Walton, Kleinman and Rifas-Shiman 29 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Wall and Fulkerson 30 ). In an effort to guide the development of interventions aimed at increasing the number of families who engage in regular family meals, it is important to explore mechanisms that may lead to the intergenerational transmission of family meals or changes in patterns across generations( Reference Fulkerson, Larson and Horning 31 ). Researchers have begun to explore potential mechanisms by which the routine of eating family meals is passed between generations( Reference Watts, Berge and Loth 32 , Reference Berge, Miller and Watts 33 ). A study by Watts et al., which utilized data collected as a part of the ongoing Project EAT (Eating and Activity in Adolescents and Young Adults) cohort study, found that frequency of family meals and the idea that family meals were ‘expected’ during adolescence were associated with family meal frequency during early parenthood( Reference Watts, Berge and Loth 32 ). Using the same data set, Berge et al. examined intergenerational transmission of regular family meals from adolescence into parenthood; results indicated that young adult parents who reported having regular family meals as an adolescent and as a parent (‘maintainers’), or who started having regular family meals with their own families (‘starters’), reported more healthful dietary intake, weight-related behaviours and psychosocial outcomes compared with young adults who never reported having regular family meals (‘nevers’)( Reference Berge, Miller and Watts 33 ). A retrospective study by Friend et al. found that recalling frequent family meals during childhood was associated with engaging in family meals as a parent, as well as having more family meal routines and higher expectations for their family meals with their current family( Reference Friend, Fulkerson and Neumark-Sztainer 34 ). Overall, qualitative work exploring intergenerational family meal transmission has found that parents’ childhood mealtime experiences, good and bad, impact their choices about how to engage in mealtimes with their own children; a common theme across several studies was that parents desire to improve upon their own eating experience to make things better for their child( Reference Trofholz, Thao and Donley 35 – Reference Dallos and Denford 37 ). Taken together, these quantitative and qualitative findings suggest that a parent’s own childhood experience with family meals has an impact on the routines and expectations he/she has for meals with his/her own family.

Using a subset of the Project EAT parent sample, the present study sought to step beyond the field’s current knowledge of intergenerational family meal transmission by using a novel mixed-methods approach to provide rich description of what may influence the transmission of family meal patterns across generations. This mixed-methods study used one-on-one interviews completed during 2016–2017 with parents of children of pre-school age (2–5 years), who also completed a survey during 2015–2016 as part of the ongoing Project EAT cohort study, to explore the similarities and differences among parents’ qualitative accounts of prior childhood experiences and current contextual factors around family meals across quantitatively informed categories of family meal frequency patterns from childhood to now as a parent. By better understanding the reasons why certain parents maintain their parents’ family meal practices and others may diverge, results from the study may help to identify relevant opportunities for interventions that support all families in positive family meal experiences.

Methods

Study participants

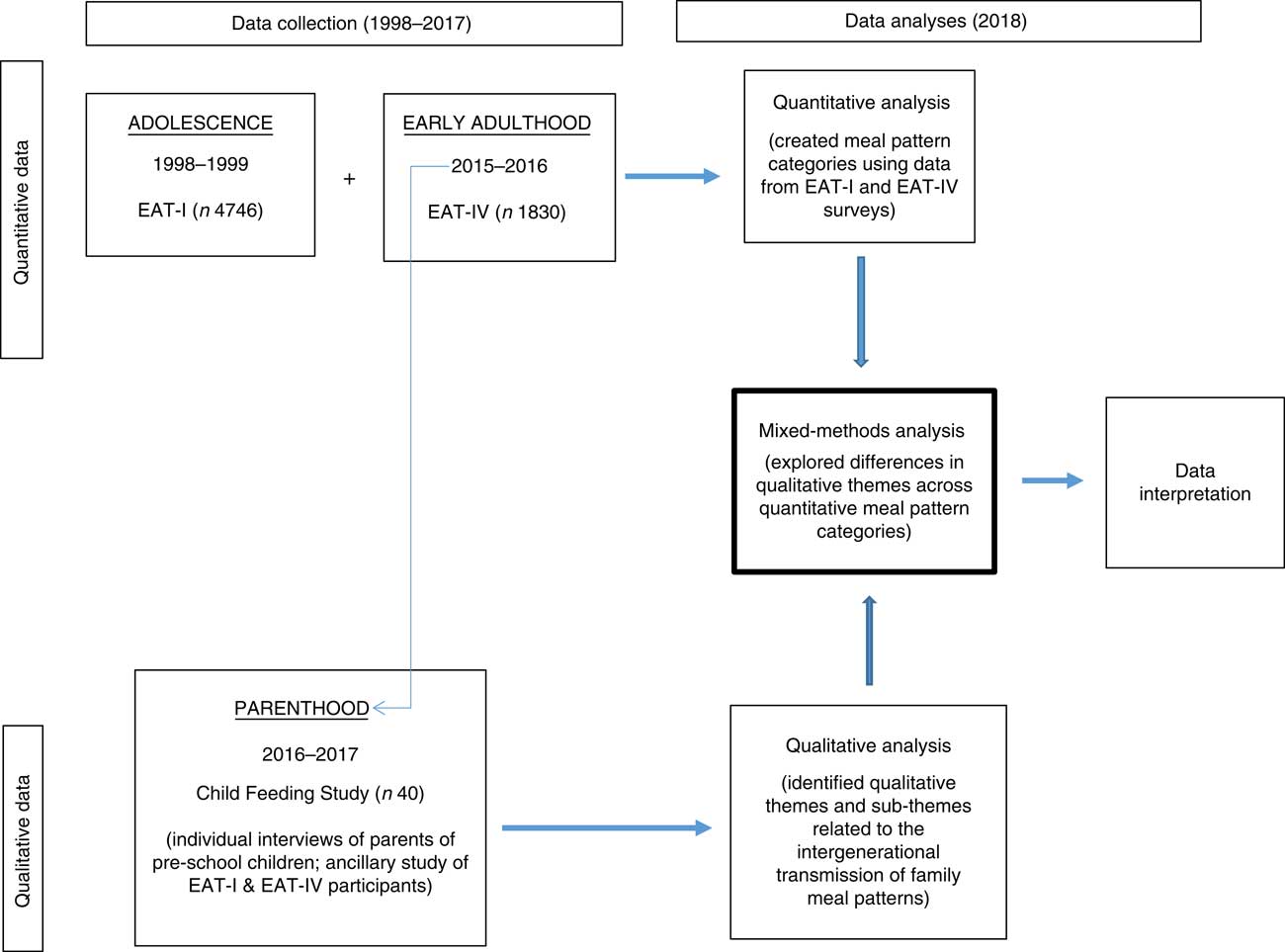

Participants in the current mixed-methods study were Project EAT participants who completed both (i) a self-report survey at Wave 1 (1998–1999; EAT-I) and Wave 4 (2015–2016; EAT-IV) of Project EAT and (ii) a one-on-one interview as part of an ancillary study (i.e. Child Feeding Study) in 2016–2017 with Project EAT parents of children aged 2–5 years old. Project EAT is a longitudinal study on eating and weight-related health during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood( Reference Watts, Berge and Loth 32 , Reference Berge, MacLehose and Meyer 38 ), and in 2016–2017, an ancillary qualitative study was conducted to further explore parents’ experiences of feeding their pre-school child and the factors influencing the choices they made about feeding. Parents of children of pre-school age were targeted in the ancillary study as both parents and the home environment are a primary influence for children in this young age group. The participant sample for the current study includes forty parents. Figure 1 presents details on data collection and the analysis timeline.

Fig. 1 (colour online) Data collection and analysis flowchart (EAT-I, wave 1 of Project EAT; EAT-IV, wave 4 of Project EAT; Project EAT, Eating and Activity in Adolescents and Young Adults)

Participant recruitment

Project EAT study participants were recruited as students (n 4746) in 1998–1999 from thirty-one public middle and high schools in Minneapolis–Saint Paul, MN, USA. Students completed self-report surveys and anthropometric measures during selected health/physical education classes. In 2015–2016, all participants in the original sample who could be contacted were invited to complete the EAT-IV survey (1830 completed the survey), which was designed to follow up on the participants as they were progressing through young adulthood at a time of life when many participants would become parents. In 2016–2017, a convenience sample of EAT-IV parent participants was then recruited to participate in the ancillary Child Feeding Study. Eligibility criteria included having at least one child aged 2–5 years who lived with them at least 50 % of the time at the time of the EAT-IV survey. Participants meeting these criteria (n 492) were then invited by email to participate in a study of qualitative interviews to learn more about parents’ experiences feeding their pre-school aged child. Participants were recruited in randomly selected batches of twenty parents and recruitment ended when theoretical saturation was reached( Reference Sobal 39 , Reference Strauss and Corbin 40 ). Participant demographic characteristics are included in Table 1.

Table 1 Intergenerational family meal patterns by demographic characteristics among parents of children of pre-school age; a subset of Project EAT (Eating and Activity in Teens and Young Adults), 2016–2017

‘Maintainers’ (n 9) reported having regular family meals both at baseline and 15-year follow-up. ‘Starters’ (n 24) reported not having regular family meals at baseline but having regular family meals at 15-year follow-up. ‘Inconsistents’ (n 7) reported having infrequent/irregular family meals at baseline and at 15-year follow-up (see text for details).

Data collection

Quantitative

At EAT-I, participants self-reported demographic information on their sex, age and ethnicity/race. At EAT-IV, participants self-reported their income, employment status and educational attainment, in addition to the number of children they have, their ages and their current custodial arrangement. At both time points participants reported family meal frequency by responding to the following question: ‘During the past seven days, how many times did all, or most, of your family living in your house eat a meal together?’ Response options included: ‘never’, ‘1–2 times’, ‘3–4 times’, ‘5–6 times’, ‘7 times’ and ‘more than 7 times’ (test–retest: EAT-I, r=0·70; EAT-IV, r=0·64). Responses to these questions were used to categorize participants into an intergenerational family meal pattern trajectory; the categorization scheme utilized was based on previous research conducted by Berge et al. (details below)( Reference Berge, Miller and Watts 33 ).

Qualitative

The research team conducting the parent interviews comprised one faculty member and three graduate research assistants. The research team members were between the ages of 20 and 40 years, and represent a combination of Caucasian, Hispanic and Asian racial/ethnic groups. Before data collection, a series of research team meetings were held where research team members were trained in qualitative data collection methods( Reference Krueger and Casey 41 ) and standardized interview protocols( Reference Miller and Crabtree 42 ); to improve reliability and consistency of interview methods, research assistants conducted several practice interviews and observed at least one participant interview (conducted by K.A.L.) prior to conducting interviews independently.

Semi-structured interview guides were used and questions covered a range of topics related to child feeding and weight-related behaviours. Questions specific to the current analysis of intergenerational transmission of family meal routines (Table 2) were based on: (i) Family Systems Theory tenets regarding intergenerational transmission of family patterns/practices( Reference Broderick 43 ); (ii) recommendations from the literature to explore intergenerational transmission of mealtime practices( Reference Fulkerson, Larson and Horning 31 ); and (iii) gaps in the extant literature on family meal routines and child feeding practices. Specific interview questions explored parents’ family meal practices when they were children; what practices they had transmitted to their own children; and the role of their partner and their partner’s upbringing in their current family meal practices. The overarching goal of these questions was to deepen our understanding of what might influence the intergenerational transmission of family meal patterns. The interview guide was first piloted with two content area experts, three graduate students and four parents of children aged 2–5 years to make sure questions were clear, elicited in-depth discussion and were acceptable to participants; feedback from pilot testing was used to modify the wording, content and order of interview questions prior to fielding.

Table 2 Semi-structured interview guide

Although interviews were semi-structured, probes were used to facilitate fuller responses to questions. Interviews ranged in length from 30 to 60 min. The majority of interviews (n 30) took place in a private room on the university campus, while ten interviews took place over the telephone due to the participant not living locally or having other barriers to meeting in person (e.g. childcare challenges). There were no major differences between in-person interviews and phone interviews with regard to interview length and participant responses. Interviews were audio-recorded and written consent from participants was obtained before commencing the interview. All study protocols were approved by the University of Minnesota’s Institutional Review Board Human Subjects Committee.

Data analysis

Quantitative

Following the approach in Berge et al., we first created a binary variable to define the regularity of family meals reported on the EAT-I (1998–1999) and at EAT-IV (2015–2016) surveys, with five or more family meals per week categorized as ‘regular’( Reference Berge, Miller and Watts 33 ). Initially, four family meal frequency patterns were created including: ‘nevers’, ‘starters’, ‘stoppers’ and ‘maintainers’. ‘Nevers’ (n 4) reported not having regular family meals both at EAT-I and EAT-IV; ‘starters’ (n 23) reported not having regular family meals at EAT-I but having regular family meals at EAT-IV; ‘stoppers’ (n 3) reported having regular family meals at EAT-I but not at EAT-IV; and ‘maintainers’ (n 9) reported having regular family meals both at EAT-I and EAT-IV. Upon further review of participant responses, the ‘never’ and ‘stopper’ categories were collapsed and re-named ‘inconsistent’ because all participants reported eating at least some family meals at both time points, making ‘inconsistent’ a more apt description of this group. Previous research( Reference Berge, Miller and Watts 33 ) using this categorization scheme found that family meal frequency patterns over time tended to be similar across the following sociodemographic characteristics: sex, race/ethnicity, socio-economic status and number of children living in the home; the lack of demographic differences between the ‘never’ and ‘stopper’ categories within the larger Project EAT sample provided additional evidence that collapsing these two categories was an acceptable approach. The current study builds on and expands this prior study by conducting an in-depth examination of parents’ perspectives of what factors influenced whether they continued the family meal routines (i.e. regular or irregular family meals) experienced in adolescence now as a parent.

Qualitative

Audio-recorded interviews with parents (n 40) from the 2016–2017 ancillary study were transcribed verbatim and coded using a hybrid deductive and inductive content analysis approach( Reference Elo and Kyngäs 44 , Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldana 45 ) using NVivo10 software (2014; QSR International Pty Ltd, Burlington, MA, USA). The hybrid deductive/inductive qualitative approach allowed the initial research questions to guide the development of the coding tree (deductive), while also allowing for unique data-derived concepts and themes to be identified (inductive). After an initial coding tree was created (by K.A.L.), coding of all interview transcripts was conducted by two coders (K.A.L. and M.J.A.U.) in multiple stages: (i) line-by-line coding of all interviews; and (ii) organization of codes into initial themes/sub-themes. The two coders met after each stage of coding to review all coding decisions; discrepancies revealed at each stage were discussed until agreement was reached and then both coders moved on to the next stage( Reference Guba and Lincoln 46 – Reference Patton 48 ).

Mixed methods

The quantitative survey data and qualitative interview data were then merged during a final stage of analysis. In particular, after the initial round of coding and theme development, qualitative data were stratified by the three quantitatively informed groups based on intergenerational family meal patterns (described above): ‘maintainers’ (n 9), ‘starters’ (n 24) and ‘inconsistents’ (n 7). Codes and initial themes and sub-themes were then further analysed using a matrix that facilitated comparisons across the three intergenerational family meal pattern groups. This process led to further refinement of overarching themes as well as sub-themes for each intergenerational family meal pattern group.

Results

We identified four overarching themes regarding influences on intergenerational transmission of family meals, including: (i) early experiences; (ii) influence of the partner; (iii) household skills; and (iv) parent priorities. For each of these overarching themes, sub-themes were identified within each of the intergenerational family meal pattern groups (‘maintainers’, ‘starters’, ‘inconsistents’). Below, we provide a description of each overarching theme and sub-themes for each family meal pattern group along with illustrative quotes. Table 3 highlights overarching themes, sub-themes and associated quotes by intergenerational family meal pattern group.

Table 3 Overarching qualitative themes and sub-themes across quantitative categories of intergenerational family meal patterns emerging from interviews with parents of children of pre-school age; a subset of Project EAT (Eating and Activity in Teens and Young Adults), 2016–2017

Early experiences

The majority of participants in the ‘maintainers’ family meal pattern recalled family meals as being expected and reported having positive memories associated with eating family meals during childhood and adolescence. For many, these positive memories played a role in their decision to continue the tradition of family meals with their own children. For example,

‘I mean, I always really enjoyed that time of like sit down and conversation, and my dad would even quiz me on like math problems, so it was kind of like an interactive time. I wouldn’t say it was chaotic by any means. It was definitely like a sit-down meal, and that, to me, growing up I think was a huge – I mean, if I remember it so vividly, I would call it a pretty impactful moment, so that’s kind of the same moments we’re trying to carry forward to my kids as well.’ (Father)

Participants in the ‘starters’ family meal pattern described having mixed memories of their early meal experiences, with some participants describing occasional meals eaten together and others not having any strong childhood memories of eating with their family. For example, one participant said,

‘Growing up, I came from a family that, if we remembered to eat, it was great, but no one in my family was really big on food (or eating together).’ (Mother)

Further, many participants in this group talked about having fewer opportunities to learn or practice food preparation or meal planning skills during childhood. For example,

‘I’ve tried to change [from how things were when I was a child], because my mom was one who never meal planned, and we ate out a lot, tons. And so I’d come home from school, and I remember my mom would be standing at the pantry looking in there, being like, “What should we have for dinner?” You know, it’s 4:30, and then she didn’t know or she didn’t have groceries, so we’d get in the car and we’d go out to eat.’ (Mother)

Several families in the ‘inconsistent’ pattern discussed having fewer memories or less positive memories of eating family meals as a child. One participant recalled,

‘So I guess I remember we [my sisters and mom] used to take turns cooking dinner or something like that, but I don’t remember a lot of meals besides special occasions or holidays.’ (Mother)

Role of partner

The majority of parents in the ‘maintainers’ pattern discussed the fact that their partners shared a similar childhood tradition of eating regular family meals, which made it easy for them to prioritize carrying forward this same tradition with their children. For example,

‘We both [my wife and I] were raised in a family that always ate together. Always.’ (Father)

The few participants in this pattern whose partners did not eat family meals during their childhood discussed that their partner seemed to appreciate or understand the value of family meals, despite not having engaged in them themselves. One participant described,

‘I think, once we started combining our two ways of doing things when we first were married, he just kind of naturally felt more comfortable about my way of doing things, … and so he seemed to kind of like my way of doing things better, and so that’s kind of just how we naturally fell into place before we had kids, and that has continued with the kids.’ (Mother)

Several participants in the ‘starter’ pattern shared that it was the influence of their partner that led them to start to eat family meals, as their partner brought with them new family traditions or values around eating together. As described by one participant,

‘They [husband’s family] always had a really strong family base and doing – like they’d always eat together, and wash the dishes after meals. That was always their big thing. And so we [my husband and I] kind of brought that into our home and helping out afterwards and washing dishes and having the family environment is important to us.’ (Mother)

Several families who were part of the ‘inconsistent’ family meal pattern discussed the role that work and schedule conflicts with their partner played in their inability to have consistent family meals. Some participants talked about how eating together was a priority for their family and emphasized that when their schedule allowed them to, they always took advantage by having meals with their family. For example, one participant said,

‘Well, this summer I was on first shift at my work. I was able to get off at 3:00 in the afternoon, and come get the kids, and come home and make dinner, but now I’ve got shifted back to the second shift, so currently it’s just my wife and those two at dinnertime. Sometimes I’ll get home early enough, and they’ll be still sitting at the table, and I’ll join them, then generally all four of us around the table, trying to have a family meal, with no distractions.’ (Father)

Household skills

Many participants across meal pattern groups discussed the impact that specific household skills had on their ability to eat home-cooked family meals. Participants in the ‘maintainer’ pattern noted that either they or their partner (or both) felt confident in their food preparation and meal planning skills, which made it easy for them to carry on the tradition of family meals. For example, one participant said,

‘We are absolutely comfortable [cooking]. We watch cooking shows and have far too many cookbooks that we never read, and cooking emails. Yeah, we keep working on it, and we’ll try something and it won’t work, and we’ll try it again a little bit differently the next time.’ (Mother)

Participants in the ‘starter’ category exhibited some diversity around who possessed the household skills, but in all instances at least one of the parents had developed the skills for family meals. Several indicated that they developed cooking skills during adulthood and went beyond their own parents’ skills, which made them more confident to prepare a wider variety of foods for their family. For example,

‘My mom always laughs and says, “I don’t know where your cooking skills came from,” but you just learn. You just do and learn and practice and try.’ (Mother)

Some also discussed developing meal planning skills, which allowed them to plan ahead for the shopping and food preparation that goes into making a family meal. Alternatively, some participants discussed the important role of the cooking and meal planning skills that their partner brought into their household. For example, one participant said,

‘His parents were very good cooks and adventurous with their cooking style, so I think that he has that too and brings that in, where he’ll just kind of cook anything and try anything.’ (Mother)

The cooking and meal preparation skills described by participants in the ‘inconsistent’ pattern were quite mixed; some participants described feeling limited by their lack of skills, whereas others noted that they had the skills they needed to plan and prepare meals but did not do so consistently for a variety of other reasons. For example,

‘Well, I’m not really much of a cook, so I’ve got two meals, and part of it is because if I’m cooking, it’s because [my husband is] working late, and so I’m watching two kids and trying to put a meal together. So my cooking involves frozen pizza, chicken nuggets, fish sticks, mac and cheese, like really simple food that the kids actually eat.’ (Mother)

Further, some participants described feeling like only one adult in their family had the skills needed, which meant that when that person was not available then family meals were not eaten. For example, one participant said,

‘My wife’s a really good cook, and I could burn water. Yeah, so I – so that’s something that I actually want to get better at, because whenever my wife’s gone, then I find myself relying on a frozen pizza or macaroni and cheese. ... I want to give my kids a good base for growing up, you know, that they start getting the good habits in. But right now, I don’t know. That’s kind of my wheelhouse – is easy, unhealthy things, or like eating out at [fast-food locales].’ (Father).

Parent priorities

Many participants who had maintained or carried on the tradition of eating family meals with their own family discussed how their desire to maintain this tradition with their family significantly influenced their practice of having family meals as a parent. Several participants in the ‘maintainer’ pattern also reflected on the types of foods they ate growing up and noted that they have prioritized preparing and serving healthier food options for their children. For example, one participant said,

‘And so, you know, I’m trying to break the cycle and give her more variety and things that I was ever exposed to when she is a kid, so I can show my kids and give them a good base for cooking at home and family dinners and things like that.’ (Mother)

Another participant stated,

‘I would say we try and eat ourselves and feed our daughter less processed kind of foods than we probably ate growing up. I mean, I remember growing up eating a lot of like frozen microwave stuff like for a snack or something. My mom would always cook like a good meal for dinner, but for a snack or lunch when I’m on my own or whatever, you know, and I would just eat a lot of processed junk. I probably drank a lot more pop. We’re trying not to do that.’ (Father)

Participants within the ‘starter’ pattern discussed the significance of making family meals a priority; some talked about rearranging work schedules or limiting evening activities, whatever needed to be done to make sure that they preserved this time with their family for most evenings. For example, one participant said,

‘I remember having specific like conversations, especially when you’re signing your kids up for sports and you’re looking at times. If there were options, we’d always sign up for a later time so we could make sure it didn’t run into the dinner hour. Now, it could change when they’re older, ... but I love our dinnertimes together.’ (Mother)

A few parents within the ‘starter’ pattern talked about the desire to do things differently with their children from the way their parents had done things with them. Some parents discussed this desire broadly; for example, one parent said,

‘I’ve intentionally done things differently [than my parents]’ (Mother)

whereas another said,

‘So some traditions we’re trying to carry on and then other things we’re intentionally going against, you know, a reversal of what we grew up with.’ (Father)

Other parents were more specific about these differences; for example, one parent discussed trying to limit eating out through meal planning,

‘Yeah, I’ve really tried to change, because my mom was one who never meal planned, and we ate out a lot, tons. [Now] we probably eat out once a week, or we get pizza once a week because it’s fun for the kids, and it gives me a break, honestly, once a week. But I have tried to meal plan so we wouldn’t be eating out so much – so I would have all the groceries for the week.’ (Mother)

For families in the ‘inconsistent’ meal pattern category, preparing and eating dinner together as a family was not or was inconsistently a top priority. Some participants talked about prioritizing ‘relaxed rules’ over strict mealtimes together as a family. Many participants in this group discussed general inconsistency in their expectations for mealtimes. As one participant said,

‘I find myself being like, “Okay, come sit down. Okay, come sit down. Come sit down.” And it’s like – so I think it’s good for him. I’m like, “Please come up here and eat.” But sometimes I’m like, “Whatever. I don’t care. Sit under the table.” So I’m not super consistent at all.’ (Mother)

Discussion

The current mixed-methods study aimed to expand current knowledge of intergenerational family meal transmission by illuminating how parents’ perceptions/accounts about what influences family meals map onto intergenerational family meal patterns. Specifically, the study used one-on-one qualitative interviews with parents to understand childhood experiences and current contextual factors around family meals across different quantitatively informed categorizations of intergenerational family meal patterns. Findings revealed salient variation within each overarching theme around family meal influences (early childhood experiences, influence of partner, household skills and family priorities) across the different intergenerational family meal patterns (‘maintainer’, ‘starter’, ‘inconsistent’), in which ‘maintainers’ had numerous influences that supported the practice of family meals; ‘starters’ experienced some supports and some challenges; while the ‘inconsistent’ group experienced many barriers to making family meals a regular practice.

Participants who reported eating frequent family meals during adolescence as well as during adulthood (‘maintainers’) shared a common set of early childhood experiences that led them to prioritize carrying on the tradition of eating family meals; eating meals with their family during their childhood was expected and routine, as well as an overall positive experience. Many ‘maintainers’ had partners who either shared a similar tradition of eating family meals, or, at minimum, appreciated the value of adding this type of routine to their current family. Finally, one or both partners possessed the skills needed to plan and prepare family meals. Interestingly, several participants in this category discussed their goal to serve healthier food to their children than they ate as a child; for these participants it seemed that because they came into adulthood with the skills needed to prioritize, plan and prepare family meals, they felt capable of working to improve upon the types of foods served during their childhood.

For the participants who did not engage in frequent family meals as children but began to engage in family meals as adults (‘starters’), the ‘desire to do things differently’ with their own family was frequently discussed. Their desire to do things differently led them to prioritize eating meals with their family and to work to overcome barriers, such as lack of cooking or meal planning skills, in order to make this priority a reality. For some, this meant that they taught themselves to cook or spent time developing organizational skills and planning strategies that extended well beyond what they learned from their own parents. For others, their partner played a strong influential role in their ability to begin the tradition of eating family meals by bringing new traditions or skills sets into their relationship that made eating regular family meals more doable.

The group of participants who engaged in family meals only inconsistently or irregularly, both during childhood and with their own families (‘inconsistents’), was quite heterogeneous in terms of what kept them from eating regular family meals. Some members of this group placed a high value on family meals, but faced significant barriers, including challenging schedules and limited cooking/meal planning skills, that interfered with making regular family meals a reality. Some of these participants talked about how they would eat family meals when their schedules permitted (e.g. weekend mornings or holidays). Other individuals in the ‘inconsistent’ meal pattern discussed the role of competing priorities; for example, a few parents talked about prioritizing their child’s freedom to eat when and where they wanted, over eating as a family. Overall, this group reported fewer memories or less positive memories of eating family meals as a child, and faced several barriers including inconsistent levels of cooking and food preparation skills and challenging evening schedules.

The extant literature on routines and rituals provides a useful framework to assist with interpretation of the findings from the present mixed-methods study( Reference Fiese, Tomcho and Douglas 49 ). Family routines and rituals both refer to specific, repeated practices that involve two or more family members( Reference Fiese, Tomcho and Douglas 49 ). Yet they are distinct and can be contrasted along the dimensions of communication, commitment and continuity( Reference Fiese, Tomcho and Douglas 49 ). Family routines are characterized by communication that is instrumental (e.g. this is what needs to be done), involve a momentary time commitment and are repeated regularly, but hold special meaning( Reference Fiese, Tomcho and Douglas 49 ). Family rituals, on the other hand, involve symbolic communication (e.g. this is who we are)( Reference Fiese, Tomcho and Douglas 49 ). The time commitment and continuity involved in the performance of rituals moves beyond the current moment and can include repetition across generations( Reference Fiese, Tomcho and Douglas 49 ). Although rituals and routines are distinct, they are often interwoven in daily interactions. Family meals are frequently used as an example of an activity that is not purely a routine or a ritual, but rather contains features of both( Reference Fiese, Hammons and Grigsby-Toussaint 50 , Reference Fiese, Foley and Spagnola 51 ). Findings from the present study highlight examples of the blending of ritual and routine and the themes that emerged suggest that the strength of meal-related routines and rituals plays a role in the intergenerational transmission of family meals. For example, it is easy to identify the role that firmly established routines (e.g. food preparation and meal planning skills) and rituals (e.g. value placed on the tradition of meals eaten together) played in the maintenance of regular family meals from one generation to the next, whereas families within the ‘inconsistent’ intergenerational family meal trajectory described fewer routines and rituals surrounding meals, both during childhood and adulthood. Families in the ‘starter’ trajectory described working to develop and maintain routines that allowed them to start having regular family meals; perhaps maintenance of these routines over time will allow these family meals within these families to become more of a ritual. Future research on family meals should continue to explore the role of routines and rituals in the maintenance and disruption of intergenerational family meal patterns; and interventions focused on the maintenance of family meals or seeking to encourage families to begin eating together should consider using a routines and rituals framework to guide their programme development.

Findings from our mixed-methods study support and extend prior quantitative work on intergenerational transmission of family meals( Reference Fulkerson, Larson and Horning 31 – Reference Berge, Miller and Watts 33 , Reference Trofholz, Thao and Donley 35 ) by providing rich, detailed information on factors that distinguish how different family meal patterns are passed between generations. That said, it should be noted that although study participants were drawn from a large, population-based sample, this sample is over-represented by white, upper middle class, college educated parents and therefore is not representative of the population at large. Future work should seek to understand if parents of diverse racial/ethnic and socio-economic backgrounds describe similar factors as influencing intergenerational family meal transmission. Further, given that ‘influence of partner’ emerged as a salient theme, future research on intergenerational transmission of family meals should consider collecting information from both parents. Finally, the number of participants within each of the family meal pattern groups was relatively small and findings should be interpreted with this limitation in mind. Future research should consider the use of cluster analysis to investigate whether salient sub-themes identified within this small sample exist at a population level.

Conclusion

The current study adds significantly to the literature by illuminating specific details about what may influence the transmission of family meal patterns across generations (early experiences, partners, skills, priorities) and identifying specific opportunities for clinicians and public health professionals to intervene to support positive family meal experiences for all families. Specifically, clinical and public health interventions should seek to provide young people with opportunities to learn and practice cooking and meal planning skills during adolescence or young adulthood. Across groups, possessing cooking and planning skills was paramount to making regular family meals a reality; among ‘maintainers’ these skills were ingrained, allowing them to move towards a focus on improving the healthfulness of meals served, whereas among ‘starters’ these skills were developed, allowing them to take on the new tradition of having regular family meals, and among the ‘inconsistent’ group, lack of skills was cited as a barrier. Study findings also suggest the important role that partners play in the development and maintenance of household routines, indicating that future family meal interventions should seek to reach all adults within the home environment. Finally, given the important role that childhood memories played in the transmission of family meals across generations, an effort should be made to reach out to parents for whom family meals during their childhood were not routine or positive, with the goal of helping them to develop an understanding of how and why they might work to incorporate this tradition/ritual into their own family. Primary care providers should consider facilitating a discussion with parents about their former and current family meal routines, as well as educating parents on the health benefits of shared mealtimes, during paediatric primary care visits.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The completion of this research would not have been possible without the hard work of student volunteers: Anne Hutchinson, Abbie Lee and Junia Nogueira de Brito. Financial support: This work was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Principal Investigator K.A.L., grant number K23-HD090324-01A1); the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Principal Investigator D.N.-S., grant number R01HL116892); and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (postdoctoral fellowship M.R.W., Principal Investigator R. Jeffery, grant number T32DK083250). Content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Authorship: K.A.L. obtained funding for the study; recruited participants; conducted interviews; coded qualitative data; developed final qualitative themes; conducted quantitative data analysis; wrote the initial draft of the manuscript; and coordinated revisions to the manuscript. M.J.A.U. coded qualitative data; developed final themes; and assisted with writing and thorough review of the manuscript. M.R.W. assisted with the analysis approach and the development of final themes; assisted with quantitative data analysis; and assisted with writing and thorough review of the manuscript. D.N.-S. helped develop the interview guide and the recruitment plan; and assisted with writing and thorough review of the manuscript; she is also the Principal Investigator for the parent study from which participants were recruited, Project EAT. J.O.F. assisted with writing and thorough review of the manuscript. J.M.B. helped develop the interview guide and the recruitment plan; and assisted with writing and thorough review of the manuscript. All authors have read, approved and provided critical revisions to the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board. Written or verbal consent was obtained from all subjects. Verbal consent was witnessed and formally recorded.