Linear growth faltering in childhood, also familiarly known as stunting, is a major global health concern( Reference Humphrey and Prendergast 1 ). Stunting has both short-term and long-term consequences on health and development throughout the life cycle( Reference de Onis and Branca 2 – Reference Stewart, Iannotti and Dewey 4 ) as well as across generations( Reference Martorell and Zongrone 5 ). Nearly half of all deaths among children under 5 years of age (under-5s) are attributable to undernutrition, which has both direct and indirect impacts on economic productivity and growth( 6 ). It has been estimated that stunting can reduce a country’s gross domestic product by up to 3 %( 7 ) and that as adults, stunted children earn 20 % less than the non-stunted( Reference Grantham-McGregor, Cheung and Cueto 8 ).

The causes of stunting are multisectoral and multifactorial. The WHO conceptual framework on childhood stunting describes the complex interaction of household characteristics; water, sanitation and hygiene; environmental issues; socio-economic status; and cultural influences with childhood stunting( Reference Stewart, Iannotti and Dewey 4 ). Causes of malnutrition in early childhood have also been extensively analysed by both Fenske et al. ( Reference Fenske, Burns and Hothorn 9 ) and Goudet et al. ( Reference Goudet, Griffiths and Bogin 10 ). These authors have classified the determinants of childhood stunting into immediate (individual level), intermediate (individual/household level) and underlying (maternal, household and regional level) factors.

Globally, although the prevalence of stunting is dropping, there are still around 156 million under-5s who are stunted( 11 ). In 2015, Asia was the home to 56 % of all stunted under-5 children, while Africa’s share was 37 %( 11 ). The prevalence of stunting among under-5s has decreased by an average of 2·7 % per year (from 51 to 36 %) between 2004 and 2014 in Bangladesh( 12 ). This is far below the targeted annual reduction of 3·3 %, necessary to meet the World Health Assembly target of 40 % reduction by 2025. Therefore, Bangladesh is less likely to achieve the World Health Assembly target for reducing childhood stunting with the current pace of reduction( 6 ).

Bangladesh has experienced rapid urbanization in recent years and is expected to have more than 50 % urban population by 2050( 13 ). As a result, more people are residing in urban slum settlements – a number currently estimated to be 2·2 million( 14 , 15 ). Congested living conditions, poverty, lack of knowledge on nutrition, and improper hygiene and sanitation facilities all make slum dwellers more vulnerable to recurrent infections which result in health and nutritional deprivation( 16 , Reference Ahsan, El Arifeen and Al-Mamun 17 ). Evidence also suggests that the prevalence of stunting among under-5s is higher among children living in these slums compared with the overall urban population of Bangladesh (40 v. 26 %)( 18 ).

Given the situation, careful exploration of the most important determinants of stunting is critical for governments and development partners. This would enable them to make strategic decisions to reduce the stunting prevalence as well as to plan, design and monitor effective interventions( 12 , Reference Ahmed, Hossain and Mahfuz 19 ). However, only a few studies have been conducted to date focusing on comprehensively explaining the myriad factors associated with childhood stunting( Reference Ahmed, Hossain and Mahfuz 19 – Reference Hossain and Khan 22 ). Furthermore, it is broadly accepted that the first 1000d from conception through the first 2 years of life is the most critical period for stunting( Reference Black, Victora and Walker 3 , Reference Leroy, Ruel and Habicht 23 ). Therefore, the present study was carried out to identify the risk factors of stunting at different levels (i.e. individual, maternal and household) among Bangladeshi children aged 0–23 months.

Methods

Study design and participants

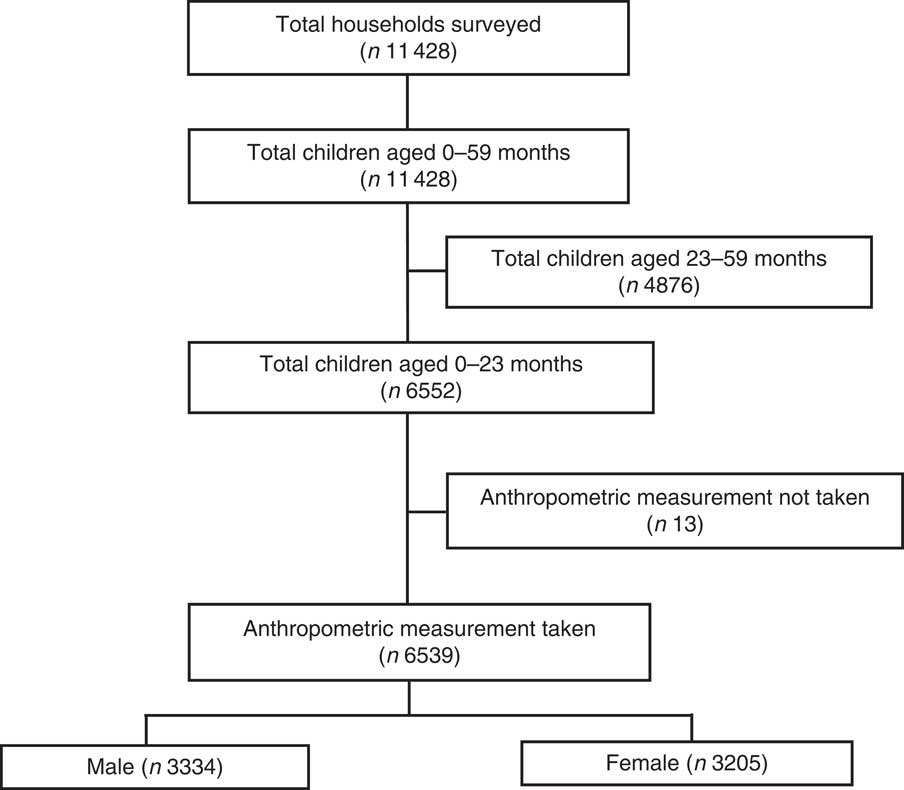

The data used for the present study were part of a nationwide cross-sectional health-care survey carried out between October 2015 and January 2016. The base survey was conducted by Building Resources Across Communities (BRAC) to explore the overall health status of children, mothers and senior citizens of rural areas and urban slums in Bangladesh. The survey excludes urban non-slum areas as BRAC operates its health interventions in rural areas and urban slums only. A slum is defined as a cluster of compact settlements of five or more households grown unsystematically and haphazardly on government and/or private vacant land( 14 ). A two-stage cluster random sampling procedure was applied and a total of 11 428 households (response rate 94·9 %) having at least one under-5 child was selected in the base survey. In the first stage, 210 enumeration areas (EA) were selected randomly with probability proportional to EA size, with 180 EA from rural areas and thirty EA from urban slums. An EA is a union (rural areas) or ward (urban slums), which is the lowest administrative unit in Bangladesh. A complete list of unions and wards, collected from the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, was used as the sampling frame for the first stage of sampling. In the second stage, starting from the north-west corner of an EA with systematic random sample of five households, on average, fifty-four households were selected per EA to provide statistically reliable estimates for rural areas and urban slums separately. Finally, the random selection covered all administrative divisions and fifty-eight out of sixty-four districts of Bangladesh. If a household contained more than one under-5 child, the smallest child was included in the survey. The present analysis was performed among all the children (n 6539) aged 0–23 months of the selected households (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Study profile and enrolment of participants

Data collection tools and techniques

A pre-tested structured questionnaire was administered to gather information pertaining to the child, mother and household through face-to-face interview with the child’s mother. Anthropometric measurements were taken using standardized procedures. Data collection was carried out electronically in ODK (Open Data Kit), an Android-based open-source mobile platform software( Reference DeRenzi, Borriello and Jackson 24 ).

Skilled female interviewers (with health survey experience) were recruited to minimize reporting bias as the respondents were women( Reference Davis, Couper and Janz 25 ). Fifteen days of intensive training was provided to the interviewers which included lectures, mock interviews, role play and field practice at the community level. A multilayer monitoring system was employed to maintain the quality of data and several tasks such as spot checking, thorough checking and back checking of the questionnaire were performed. Any discrepancies arising were resolved through re-interviewing the respective mothers.

Variables assessed and measured

Child characteristics considered for the present study were: age in months; gender (boy/girl); birth order (1–2, 3–4, ≥5); birth weight in kilograms (<2·5, ≥2·5); immediate breast-feeding after birth (yes/no); prelacteal feeding (yes/no); exclusive breast-feeding up to 6 months (yes/no); and suffering from diarrhoea within the last 3 months (yes/no). Although the study did not collect data on exact birth weight, mothers were asked to report, according to their perception, whether their child was ‘very small’, ‘smaller than average’, ‘average’, ‘larger than average’ or ‘very large’ at birth. A birth size of ‘very small’ or ‘smaller than average’ was categorized as low birth weight (<2·5 kg), while a birth size of ‘average’ to ‘very large’ was categorized as normal birth weight (≥2·5 kg). Maternal characteristics were: age in years; level of education (no education, primary incomplete: grade 1–4, primary complete/secondary incomplete: grade 5–9, secondary or higher: grade 10 or higher); occupation (housewife/working outside), BMI in kg/m2 (underweight: <18·5, normal: 18·5–24·9, overweight: 25·0–29·9, obese: ≥30·0), age at first pregnancy in years (<20, ≥20); vitamin A supplementation immediately after delivery (yes/no); Fe supplementation during pregnancy (yes/no); using soap before eating (yes/no); and using soap after defecation (yes/no). Household-level characteristics were: administrative division (Barisal, Chittagong, Dhaka, Khulna, Rajshahi, Rangpur, Sylhet); place of residence (rural areas/urban slums); household wealth quintile (lowest, low, middle, high, highest); size of household (≤4, >4); household food security status (secure/insecure); household source of drinking-water (safe/unsafe); type of latrine (improved/unimproved); and toilet hygiene condition (hygienic/unhygienic).

Construction of the wealth index was based on factor analysis of principal component analysis of key socio-economic variables( Reference Rutstein 26 ). The variables considered were: type of wall, floor and roof of the house; ownership of a radio, television, computer, bicycle, mobile/telephone, refrigerator, wardrobe, table, chair, watch, bed, sewing machine, bike, motor vehicle and livestock; and access to solar electricity.

Age of the child was recorded from the immunization card or birth certificate. A local event calendar was used when this information was unavailable. Height was measured to the nearest 0·1 cm using a board with a wooden base and a movable headpiece, with the participant in supine position. Weight was measured with an electronic bathroom scale at 0·1 kg precision. Height and weight of the children and mothers were taken separately. BMI of the mothers was calculated using the formula( Reference Gibson 27 ): [weight (kg)]/[height (m)]2.

The UNICEF and WHO Joint Monitoring Programme’s operational definition for improved water supply, treated water and improved sanitation facilities was used( 28 ). The households were considered food insecure if they faced any food insufficiencies in the 30d prior to the survey.

Outcome measurement

The outcome variable was stunting of children aged 0–23 months. A child with height-for-age more than 2 sd below the median height-for-age of the WHO reference population (height-for-age Z-score<−2) was considered stunted( 29 ).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed to assess the distribution of the variables. The χ 2 test was used to compare the prevalence of stunting within different categories of a variable with 5 % level of significance. As the EA were scattered throughout the country with different demographic and social characteristics, there was a potential chance for certain variability in stunting prevalence among clusters. Moreover, mothers from the same EA could share certain types of unobserved cultural and environmental factors. This nested source of variability was addressed by incorporating random effects with the usual fixed effects in the model( Reference Agresti 30 ). Therefore, considering EA as clusters, the modified Poisson regression was executed to explore the factors truly associated with early childhood stunting( Reference Zou and Donner 31 ). EA were considered as random effects with exchangeable correlation among clusters, while other variables were considered as fixed effects. The parameters of the model were estimated through the generalized estimating equations approach to estimate the true effect of associated factors and the unknown correlation of the outcome among clusters( Reference Zeger, Liang and Albert 32 ). Due to the convergence problem with many covariates in the binomial model, the modified Poisson regression model was performed, which is equivalent to the binomial model while estimating the risk ratio( Reference Zou and Donner 31 ). The crude risk ratio (cRR), adjusted risk ratio (aRR) and 95 % CI were estimated at 5 % level of significance. The children’s anthropometric index was constructed in WHO AnthroPlus software and all statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software package Stata version 13.0.

Ethical approval

The guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed while conducting the study and ethical clearance was sought from the Bangladesh Medical Research Council (reference number BMRC/NREC/2013-2016/802) before the study. Both written and verbal consent were taken from the mothers of the children prior to the interview.

Results

Sample description

Of the 6539 children less than 2 years of age sampled, 23·7 % were 0–5 months old, 31·1 % were 6–11 months and 45·2 % were 12–23 months old (Table 1). The male:female ratio was close to unity (49·0 v. 51·0 %, respectively). Meanwhile, 63·4 % of mothers were 20–29 years of age and 20·5 % were aged 30 years or above. In addition, 13·6 % of children’s mothers had no education while 14·3 % had completed grade 10 or higher. Most of the mothers (94·4 %) were housewives. Also, 20·6 % of the mothers were underweight, 14·4 % were overweight and only 2·2 % were obese. More than one-third of children were sampled from Dhaka division and 86·9 % lived in rural areas. A total of 40·0 % of children belonged to poor households (20·2 % lowest, 19·8 % low; Table 1).

Table 1 Demographic and socio-economic characteristics of the sample of Bangladeshi children under 2 years old (n 6539), October 2015–January 2016

* Primary incomplete=grade 1–4.

† Primary or secondary incomplete=grade 5–9.

‡ Secondary or higher=grade 10 or higher.

Prevalence of childhood stunting

Overall, 29·9 % of children were stunted (Table 2). The prevalence of stunting increased with age of the child (P<0·001) and was higher among boys than girls (32·6 v. 27·1 %; P<0·001). The prevalence increased with higher birth order (29·2 % for the first or second child, 30·4 % for the third or fourth child, and 37·2 % for the fifth or later child; P=0·006). Stunting prevalence was also significantly higher among low-birth-weight babies (weight <2·5 kg) than babies with normal birth weight (42·0 v. 29·0 %; P<0·001). The study further showed that the prevalence of stunting was considerably lower among children who were exclusively breast-fed up to 6 months compared with those who were not (17·1 v. 32·9 %; P<0·001). Children suffering from diarrhoea episodes within the last 3 months were also more likely to be stunted (34·7 v. 29·4 %; P=0·006).

Table 2 Bivariate analysis of child, maternal and household characteristics with childhood stunting in Bangladeshi children under 2 years old (n 6539), October 2015–January 2016

Although not significant, the prevalence of childhood stunting was found to be increasing with mother’s age. However, in contrast, the prevalence of stunting decreased significantly with increasing maternal education (P<0·001). A total of 38·7 % of children whose mothers had no education were stunted, compared with 28·3 and 22·0 %, respectively, among children whose mothers had completed grade 5–9 and grade 10 or more. Maternal nutritional status, measured by BMI, also predicted decreased childhood stunting (P<0·001). Also, the prevalence of stunting was higher among children whose mothers became pregnant for the first time before the age of 20 years (P=0·020). At the same time, the prevalence of stunting was also significantly lower among children whose mother received vitamin A supplements immediately after delivery (P=0·036), received Fe supplements during pregnancy (P<0·001), used soap before eating (P=0·003) and used soap after defecation (P<0·001).

Disparity in childhood stunting prevalence was observed among households from different administrative divisions (P<0·001). The prevalence was highest in Sylhet division (41·4 %) and lowest in Khulna (24·5 %). Also, the prevalence was higher among the children from urban slums than among those from rural areas (32·3 v. 29·6 %; P=0·099). Stunting prevalence was significantly higher among children from poor households (poorest: 33·2 %, richest: 24·9 %; P<0·001). However, the prevalence was considerably lower among children from food-secure households (P<0·001), and among households with improved (P<0·001) and hygienic (P<0·001) latrines (Table 2).

Risk factors for childhood stunting

Individual assessments of each of the covariates with childhood stunting are presented in Table 3. Significant associations were observed between stunting and different child characteristics such as age, gender, birth order, birth weight, exclusive breast-feeding up to 6 months and diarrhoea episodes. Maternal characteristics such as level of education, BMI, age at first pregnancy, Fe supplementation during pregnancy, use of soap before eating and after defecation were also significantly associated with childhood stunting. Moreover, household-level factors such as administrative division, wealth quintile, food security status, type of latrine and toilet hygiene condition were significantly associated with childhood stunting.

Table 3 Association of child, maternal and household characteristics with childhood stunting in Bangladeshi children under 2 years old (n 6539), October 2015–January 2016

RR, risk ratio; Ref., reference category.

The final adjusted modified Poisson regression model captured 3 % of variation (P<0·001) in outcome among clusters. The adjusted estimated effects for the factors associated with childhood stunting are also presented in Table 3. We found that the children aged 6–11 months had 34 % higher risk of stunting than those aged 0–5 months (aRR=1·34; 95 % CI 1·11, 1·62), while children aged 12–23 months had 2·65 times higher risk (aRR=2·65; 95 % CI 2·20, 3·20). Meanwhile, boys had 21 % higher risk than girls (aRR=1·21; 95 % CI 1·12, 1·30). It was also notable that low-birth-weight babies had more than 50 % higher risk of stunting than babies with normal birth weight (aRR=1·51; 95 % CI 1·35, 1·68).

The risk of stunting was 12 % lower among children whose mothers had completed grade 5–9 (aRR=0·88; 95 % CI 0·80, 0·97) and was 22 % lower among children of mothers who had completed grade 10 or more (aRR=0·78; 95 % CI 0·67, 0·92) compared with the children of uneducated mothers. The children of underweight mothers had 11 % higher risk of stunting than those of normal-weight mothers (aRR=1·11; 95 % CI 1·02, 1·20). Meanwhile, there was 9 % higher risk of stunting among children whose mothers became pregnant for the first time before the age of 20 years (aRR=1·09; 95 % CI 0·99, 1·19).

It was found that children from Khulna division had 16 % lower risk of stunting compared with those of Dhaka (aRR=0·84; 95 % CI 0·72, 0·99), while the risk was 35 % higher among children from Sylhet division (aRR=1·35; 95 % CI 1·12, 1·64). It was also evident that children from urban slums had 19 % higher risk of stunting than those from rural areas (aRR=1·19; 95 % CI 1·00, 1·41). Also, children from the richest households had 16 % lower risk of stunting than those from the poorest households (aRR=0·84; 95 % CI 0·72, 0·98). Moreover, children from food-secure households had 7 % lower risk (aRR=0·93; 95 % CI 0·85, 1·00), households having improved toilet had 12 % lower risk (aRR=0·88; 95 % CI 0·79, 0·98) and households having hygienic toilet had 10 % lower risk (aRR=0·90; 95 % CI 0·79, 1·02) of stunting compared with their corresponding reference (Table 3).

Discussion

The present study recognized several modifiable risk factors of stunting at individual, maternal and household levels among children aged 0–23 months in Bangladesh. Although the overall stunting prevalence among children has been declining in Bangladesh over the last decade, the reduction rate is not satisfactory( 12 ). The findings of the present study suggest that an intervention considering multilevel factors might increase the reduction rate, which in turn would help to achieve the World Health Assembly targets on reducing childhood stunting.

Overall, about one-third of children were stunted and there was marked variation in stunting prevalence among children based on place of residence, region and economic status. This agrees with the findings of the most recent national Demographic and Health Survey( 12 ). The present study also found that the prevalence of stunting was comparatively higher among the children from urban slums, which may be due to lack of adequate public services as well as health and sanitation facilities in slums. This is in line with the findings of some other studies( Reference Awasthi and Agarwal 33 – Reference Islam, Sanin and Mahfuz 35 ). Furthermore, as reported elsewhere( Reference Hossain and Khan 22 ), stunting prevalence was considerably higher in Sylhet division, which is characterized by high rate of poverty, low literacy and lack of access to safe water and sanitation( 36 ).

High prevalence of stunting among young children can be attributed to chronic nutrition deprivation and poor linear growth in infancy and early childhood( Reference Aguayo, Nair and Badgaiyan 37 , Reference Jones, Ickes and Smith 38 ). The demand for nutrients increases with age and inappropriate complementary feeding may result in inadequate intakes of vital nutrients, which is one of the major causes of stunting in early childhood( Reference Shrimpton, Victora and de Onis 39 , Reference Dewey and Adu-Afarwuah 40 ). However, evidence of the positive role of exclusive breast-feeding on linear growth is surprisingly weak( Reference Bhutta, Das and Rizvi 41 ). The current study also found no significant association between exclusive breast-feeding and risk of early childhood stunting.

It is well documented in several studies( Reference Aguayo, Nair and Badgaiyan 37 , Reference Mishra, Kumar and Basu 42 ) that children born with a birth weight of less than 2·5 kg possess a higher risk of being stunted in early childhood. The present study also found that children born with low birth weight had 50 % higher risk of being stunted. The association between low birth weight and stunting in childhood can be explained by the increased vulnerability of children to infections and increased risk of complications including sleep apnoea, jaundice, anaemia, chronic lung disorders, fatigue and loss of appetite( Reference Haque, Tisha and Huq 43 , Reference Khanal, Sauer and Karkee 44 ). As reported in an earlier study carried out in Bangladesh( Reference Aguayo, Nair and Badgaiyan 37 ), the present study also found that stunting prevalence was higher among boys than girls. The explanation for this gender variation in stunting is still unclear, although some researchers have argued that this disparity is more prevalent among poor households compared with those better-off socio-economically( Reference Wamani, Åstrøm and Peterson 45 ).

Several maternal factors were also identified to be significantly associated with stunting among children under 2 years of age. It was evident that children of undernourished mothers were more likely to be stunted than those of well-nourished mothers. Maternal undernutrition is one of the major causes of intra-uterine growth retardation which contributes about 20 % of the global burden of childhood stunting( Reference Black, Victora and Walker 3 ). Moreover, stunted girls are likely to grow to be stunted women in their later life, which adversely affects growth of the fetus during their pregnancy. Suboptimal growth of the fetus often results in low birth weight at delivery( Reference Young, Nguyen and Addo 46 ), which contributes to stunting in early childhood. However, the present study showed that maternal age at first pregnancy played a pivotal role in stunting among the children, which is also supported by other studies( Reference Aguayo, Nair and Badgaiyan 37 , Reference Varela‐Silva, Azcorra and Dickinson 47 ). Furthermore, mother’s education was identified as an important predictor of stunting. Studies conducted in Bangladesh( Reference Hossain and Khan 22 , Reference Headey, Hoddinott and Ali 48 ) and India( Reference Aguayo, Nair and Badgaiyan 37 ) also confirmed that higher maternal education significantly reduces stunting among children. Another multi-country study( Reference van den Bold, Quisumbing and Gillespie 49 ) showed that 43 % of the total reduction in stunting can be attributed to improvement in maternal education. Therefore, certain nutrition-sensitive and nutrition-specific interventions targeting adolescent girls and mothers may also be central to the national efforts in reducing childhood stunting and achieving the World Health Assembly target( 6 , Reference Ahmed, Hossain and Mahfuz 19 , Reference Haddad, Achadi and Bendech 50 ). Since mothers are the main caregivers in households for young children, women’s empowerment in terms of education and decision making should also be given attention when designing nutrition intervention programmes.

At household level, children from poor and food-insecure households were more likely to be stunted( Reference Awasthi and Agarwal 33 ). This is similar to the findings of the most recent national Demographic and Health Survey( 12 ). Besides, lack of access to a sanitary latrine and unhygienic toilet condition were significantly associated with higher risk of stunting among children. This association is in line with the findings of some other previously conducted studies( Reference Fink, Gunther and Hill 51 , Reference Rah, Cronin and Badgaiyan 52 ). Therefore, to reduce stunting prevalence, policy makers should focus on reducing poverty and household food insecurity through ensuring easy access to credit, promoting small investments and social safety net transfers, subsidizing raw materials of production such as seeds and fertilizer, subsidizing the cost of medicines, and encouraging homestead gardening, among others.

However, merely implementing nutrition interventions may not necessarily ensure the desired level of reduction in childhood stunting prevalence in Bangladesh. It is also important that a suitable environment is being ensured where successful programme implementation can be achieved. A recent systematic review also highlighted that certain factors such as political stability, community mobilization, a multisectoral approach and programme delivery using community-based platforms can contribute to achieve higher rate of reduction( Reference Hossain, Choudhury and Abdullah 53 ). It is also very crucial that the poorest of the poor( Reference de Onis and Branca 2 ) and geographically vulnerable people( Reference Hossain and Khan 22 ) are given the highest priority.

We used the modified Poisson regression model with the generalized estimating equations approach in the present study while estimating the unknown correlation of outcome among clusters. Future research may also employ mixed-effect models as an alternative to using generalized estimating equations as mixed-effect models are capable of estimating the variance of multiple random or nested random effects( Reference Hubbard, Ahern and Fleischer 54 ).

The present study has several strengths over other similar studies. First, it followed a rigorous sampling method covering a large sample size of children aged less than 2 years. Second, along with the rural areas, it also covered urban slums of the country where living standards as well as health and sanitation parameters are worse than in rural areas. Thus, the inclusion of children from urban slums alongside those from rural areas greatly increases the comprehensiveness of the study. However, the study was subjected to certain limitations too. Being cross-sectional in nature, it was unable to draw out the temporal relationship between stunting and its determinants. Third, since the base study was carried out in rural areas and urban slums where BRAC operates its health and nutrition interventions, we were unable to include the children of urban non-slum areas of the country. Lastly, we had to rely on mother’s perception of the size of her child at birth instead of the exact birth weight. This is due to the fact that birth weight is not being taken for many newborn babies, particularly in cases of home deliveries in Bangladesh.

Conclusions

The present study findings urge the importance of administering a multicomponent, multidisciplinary intervention to address the issue of stunting among children aged 0–23 months in Bangladesh. Policy makers and public health practitioners should focus on specific initiatives such as quality health-care services, promotion of breast-feeding, sanitation facilities, household food security and especially on maternal education and nutrition.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors acknowledge the role of the relevant staff of the Health Nutrition and Population Programme, BRAC, for initial review of the tools and smooth arrangement of the data collection initiatives. Financial support: This research was funded by the Strategic Partnership Arrangement (SPA) between BRAC, the UK Department for International Development (DFID) and the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT). The funders had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this manuscript. Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose. Authorship: S.K.M., M.R. and K.A. contributed to the design of the study. M.B.H. conducted the data analysis and participated in interpretation of the results. S.K.M., M.B.H., M.P., F.K. and F.A. contributed to write the first draft of the manuscript. F.M.Y. commented extensively on the manuscript draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethical approval was obtained from the Bangladesh Medical Research Council (reference number BMRC/NREC/2013-2016/802). The purpose of the study was described and written informed consent was obtained from the child’s parents prior to the interview. The respondents were ensured of the confidentiality of information provided.