Children’s exposure to unhealthy food and beverage marketing has a direct impact on their dietary preference for, and consumption/intake of, these products(Reference Smits, Vandebosch and Neyens1–Reference Smith, Kelly and Yeatman5). In addition, children are particularly vulnerable to the persuasive power of marketing messages and techniques (for example, celebrity and athlete endorsements, in-store marketing and toy co-branding)(Reference Smits, Vandebosch and Neyens1,Reference Smith, Kelly and Yeatman5–Reference Elliott and Truman7) . As the burden of child malnutrition in all its forms continues to rise globally(8), the improvement of food environments through restricting children’s exposure to, and the persuasive power of, marketing practices stands out as a priority in public health nutrition policy. Restricting of food marketing is also increasingly recognised as a child rights issue, implying States’ obligation to regulate(Reference Garde, Byrne and Gokani9–Reference Tatlow-Golden and Garde13).

The WHO and its regional offices have published recommendations for policy intervention to limit the negative impact of food marketing to children and adolescents, with an aim of reducing their consumption of energy-dense and high-in saturated fat, trans fat, free sugar and/or salt products, including fast foods and sugar-sweetened beverages(14–16). WHO recommendations include that ‘marketing’ restrictions should cover not only advertising but all other commercial communications designed to promote (or have the effect of promoting) high-in saturated fat, trans fat, free sugar and/or salt foods; that States should take a comprehensive approach for the highest potential to achieve desired impacts; and that Member States should cooperate to reduce the impact of cross-border marketing(14,17) . In particular, as digital media and other forms of access to children become more widespread, it follows that regulations seeking to reduce children’s exposure to marketing of unhealthy products should expand from broadcast (primarily television) advertising bans, towards encompassing narrowcast (e.g. social media)(Reference Potvin-Kent, Pauzé and Roy18), and novel marketing techniques such as product placement, co-creation, and ‘advergaming’ (a method of interactive marketing in which free downloadable computer games appear on websites to advertise a company or product).

Restriction of marketing can in practice take many different forms. The NOURISHING Database has documented the various actions taken so far around the world in this policy area (by a total of twenty-nine countries as of December 2020), ranging from: voluntary pledges and self-regulation, to mandatory regulation; restriction of broadcast food advertising, and/or non-broadcast communications channels, to restriction in any medium, as well as restriction of marketing in schools; with most regulating only specific marketing techniques, or promotion of specific food items and beverages (such as sugar-sweetened beverages or energy drinks)(19).

Evaluations of self-regulatory regimes have shown these to be insufficient to reduce children’s exposure to this advertising(Reference Galbraith-Emami and Lobstein20–Reference Chambers, Freeman and Anderson22), with common issues being insufficiently comprehensive codes and guidelines (e.g. Norway(Reference Vaale-Hallberg23–Reference Vaale-Hallberg25)), and low compliance (e.g. Spain(Reference León-Flández, Rico-Gómez and Moya-Geromin26), Canada(Reference Potvin Kent and Pauzé27)). The case for implementing mandatory regulations restricting the marketing of unhealthy foods and beverages to children is thus increasingly strong. In 2020, nineteen countries had some form of mandatory broadcast or non-broadcast marketing restrictions (and another had mandatory restrictions of marketing in schools), though these had varying degrees of strength and coverage(19). Overall, however, countries have found it difficult to move beyond voluntary restrictions and to adopt more comprehensive regulations. Key challenges include concerns about economic impacts(Reference Thow, Waqa and Browne28), and concerns about the potential for formal constraints in the form of costly legal challenges from international trade and/or investment agreements (TIA)(Reference Garton, Thow and Swinburn29–Reference Thow, Snowdon and Labonte31). In particular, the use of TIA to challenge other forms of nutrition policy, such as mandatory interpretive labelling, suggest a need for investigation into whether such agreements may constrain governments ‘policy space’ to regulate food environments through mandatory marketing restrictions. Policy space refers to the ‘freedom, scope, and mechanisms that governments have to choose, design, and implement public policies to fulfil their aims(Reference Koivusalo, Schrecker and Labonte32).’

For example, Chile’s regulatory marketing restrictions are the world’s strictest and most comprehensive to date, in its Law No. 20.606 on the Nutritional Composition of Food and its Advertising (amended to Law No. 20.869 on Food Advertising), which prohibits any advertising or marketing of foods ‘high in’ sugar, sodium, saturated fat, or caloric value to children and adolescents under 14(33). Decree No. 13 of this law specifies that advertising is considered to be aimed at children under the age of 14:

If it uses, among other elements, children’s characters and figures, animations, cartoons, toys, children’s music, or if it includes the presence of people or animals that attract the interest of children under 14 years old or if it contains statements or fantastic arguments about the product or its effects, children’s voices, language or expressions of children, or situations that represent their daily lives, such as school, playground or children’s games. (33 Decree No. 13)

Trans-national food corporations including Canozzi, Kelloggs and PepsiCo have filed domestic court claims in Chile challenging Decree No. 13 on the basis of alleged breaches to their trademark protections, though none have been ultimately successful(Reference Tulli34). While no challenges have been raised against Chile’s mandatory marketing restrictions in international trade or investment dispute forums to date, studies have explored the potential for trade-related arguments being raised under the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS)(Reference Carreno35–Reference Dorlach and Mertenskotter37) and the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade(Reference Carreno and Dolle36–38) under the interpretation of marketing restrictions as technical regulations, which must not create ‘unnecessary’ technical barriers to the free movement of food products across borders. Another analysis asserted that, as a US company investing in Chile, trans-nationals like PepsiCo could also pursue a challenge to protect their brand investments under Chapter 10 of the Chile-US Free Trade Agreement(Reference Potočnik39).

Legal scholars have discussed the theoretical trade and investment implications of food marketing restrictions to varying degrees of detail(Reference Fidler40–Reference Campbell45). However, these analyses do not elucidate the specific implications for public health nutrition policy design, and there is little written on this topic in public health journals. Emerging research from civil society as well as a recent academic review identified the interaction of policy design settings with certain international trade and investment rules as a key factor resulting in the constraint or preservation of governments’ policy space for food environment regulations such as marketing restrictions(Reference Garton, Thow and Swinburn29,38) . A more detailed understanding of the specific interactions of TIA commitments with mandatory marketing restrictions is needed in order to guide the development of robust regulations that will avoid or withstand challenges on the basis of TIA.

Methods

Our objective was to harness inter-disciplinary expert knowledge to identify aspects of TIA which could impinge upon policy space for mandatory marketing restrictions. To do this, we explored the relationship between marketing regulation policy design and TIA-related policy space through a series of qualitative vignette interviews with experts in the field of international economic policy and marketing regulations.

Because of the multisectoral nature of food and nutrition policy (where policy space spreads across multiple sectors and multiple actors within sectors), it is essential to consider food marketing restrictions from a political economy lens(Reference Thow, Kadiyala and Khandelwal46,Reference Balarajan and Reich47) . We therefore applied a political economy perspective(Reference Reich and Balarajan48), to examine the mechanisms (political and technical) through which international trade and investment commitments could encroach on policy space for restrictions on food and beverage marketing to children. We performed a policy analysis(Reference Walt and Gilson49), informed by an approach focusing on the contexts, agenda-setting circumstances and policy characteristics that affect policy space and policy change(Reference Thow, Kadiyala and Khandelwal46,Reference Grindle and Thomas50,Reference Crichton51) . We drew on Fidler et al.’s conception of potential constrictions to public health policy space posed by TIA: substantive constriction, procedural constriction, and structural constriction(Reference Fidler, Aginam and Correa52). In terms of policy design characteristics, we apply Hall’s policy ‘settings’ (the selectable ‘order’ within a given ‘policy instrument)(Reference Hall53)’. Our underlying philosophical framework was critical realism, characterised by a realist ontology wherein causal mechanisms are both visible/empirical and intangible, and knowledge or understanding of these is constructed and fallible(Reference Fletcher54).

Study design

Three over-arching research questions guided the current study:

What are the specific trade- and investment-related constraints governments may face when considering the policy avenue of restricting marketing promotions of unhealthy food and beverages to children?

What are the specific policy design settings of importance for marketing restriction policy space?

How might contextual factors, including actors, institutions and networks, affect the mechanisms of TIA influence on policy space for marketing restrictions?

We followed an adapted ‘scenario analysis’ methodology, which explores implications of plausible alternative futures ‘in a creative, rigorous and policy-relevant manner’ that reflects a normative dimension and incorporates different perspectives(Reference Swart, Raskin and Robinson55). To do this, we designed in-depth interviews structured by a series of qualitative ‘vignettes,’ i.e. ‘short stories about individuals, situations and structures,’ set out in a series of variations that unfold in stages, based on changing key variables(Reference Hughes56). In light of our focus on the contexts, agenda-setting circumstances and policy characteristics that affect policy space and policy change, we designed these vignette scenarios to explore the potential consequences—in terms of perceived conflict with TIA and related constraint to policy space—of changing various marketing restriction policy design ‘settings’ within a specified policy context.

Data collection

We conducted nine interviews with international expert informants who had expertise and experience in the restriction of marketing unhealthy food and beverages to children and international trade and/or investment agreements (Table 1). These we identified and recruited purposively based on our knowledge of the experts in the field and authorship of key literature, as the global pool of expertise in this specific area is very small. Those we approached were primarily academics, legal professionals, government nutrition policy specialists and civil society actors, and we reached additional participants by snowballing. We did not recruit industry actors affected by policy decisions in marketing, as we expected there to be a potential commercial conflict of interest for these stakeholders. The participants in the current study were anonymised with the labels P1–P9.

Table 1 Interview participant characteristics

* There was overlap between participants in terms of their fields of expertise and sectors in which they were involved. For example, most (8/9) had acted in an advisory capacity to governments in trade negotiations and, in some cases, trade or investment disputes.

The three authors developed the policy scenario vignettes collaboratively and with input from a trade and investment legal expert advisor, based on our knowledge of best practice recommendations in marketing restriction and policy settings that had been previously identified as having potential interactions with TIA(Reference Garton, Thow and Swinburn29). These stepped qualitatively from a minimally burdensome and generally non-controversial baseline (a mandatory restriction of persuasive techniques to advertise unhealthy food/beverages to children through television advertising during children’s programs), to a ‘comprehensive’ policy that more closely resembles best practice from a population health perspective but was also expected to be more politically difficult to achieve (Table 2). The final scenario was designed to test whether policy informed by international evidence rather than local data (and therefore less burdensome for government regulators) would encounter any difference in legal risk.

Table 2 Policy settings applied in scenario design

KG conducted all interviews and asked the same Guiding Questions after each change to the vignette/scenario:

Which, if any, TIA and associated chapters and articles would apply?

Are there any potential challenges of conflict with respect to TIA?

Are there any potential supportive factors that could increase the policy space?

What would need to change in order to reduce the likelihood of policy space constriction?

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim by KG and member-checked by participants, after which KG carried out the analysis of responses in NVivoTM(57). We applied a ‘retroductive’ approach to coding, i.e. an iterative process moving between induction and deduction, consistent with a critical realist analysis(Reference Fletcher54,Reference Halperin and Heath58) . We began by establishing a set of a priori codes based on our study frameworks, including categories of policy content, policy process, policy context (including actors and institutions involved) and policy space outcomes (in terms of potential substantive, procedural and/or structural constraint). During analysis, we expanded upon these categories through iterative reading of the data, developing additional reactive codes to add to our evolving conceptual framework.

Results

Trade and/or investment agreements interactions with policy scenarios

The principal relevant WTO agreements identified by participants included: the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), TBT and TRIPS. Participants also identified international investment agreements (IIA), and regional free trade and investment agreements (FTIA) including the NZ-Australia Closer Economic Relations (CER) Agreement, the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) Agreement and its replacement, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement on Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and customs unions such as the European Community (EC), as being theoretically relevant to the restriction of marketing unhealthy foods to children (Table 3).

Table 3 General interaction of marketing restriction policy with trade and/or investment agreements

* Electronic commerce and digital trade agreement rules have been gaining prominence, with potentially serious implications for policy space to regulate marketing in the digital age(Reference Kelsey62). However, their discussion was outside the scope of the current study.

Overall, participants tended to assign low risk of TIA-related legal issues to the early scenarios with regard to these agreements (Table 4). Changes to the time of day (peak hours/watershed restrictions) and target age (to children being under 18) were deemed important under GATS as these proposed scenarios were interpreted to approach the equivalent of quantitative restrictions prohibited under market access rules. Increased risk of conflict or incompatibility with WTO agreements began to appear when scenarios proposed: broadening restrictions to include all unhealthy food/beverage advertising in broadcast and non-broadcast media (scenario 4.1), consideration of all forms of product marketing (v. advertising only) (scenario 4.2) and inclusion of brand advertising and sponsorship in the restrictions (scenario 5.0). There was more uncertainty regarding risk, which arose at an earlier stage, when considering other (‘WTO-plus’) FTIA and customs unions, because of the potential variations in text (which tend towards tighter restrictions on policy). Responses indicated minimal risk of conflict with IIA, until the proposed policy scenario began to affect brands (scenario 5.0).

Table 4 Visualisation of perceived risk of policy space constraint for each scenario, under different agreements, and rubric for spectrum of risk (below)

Key (from left to right): No TIA argument against the policy; TIA arguments hypothetical-only, but not realistic; policy should be compatible but requires justification; policy should be compatible but greater evidence burden; unpredictability (e.g. related to the specifics of commitments already made, or ability to collect the necessary evidence); possible risk or threat to policy space posed by TIA; realistic risk or threat to policy space posed by TIA; policy that will be high-risk based on certain TIA (substantive) constraints.

Disagreement between participants was based not on the nature of risk, but in the level of risk, or potential for it to actually happen (between realistic and theoretical risk). Rather, there are many ‘grey areas’ where policy space may depend upon specific factors related to policy design, context, and variations in the trade rules and commitments across agreements (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table SX). These are the areas that commercial stakeholders are likely to exploit, by advancing self-serving interpretations of the legal provisions.

Key trade and investment rules and principles

What are the specific direct and indirect trade- and investment-related constraints governments may face when considering the policy avenue of imposing regulation restricting marketing promotions of unhealthy food and beverages to children?

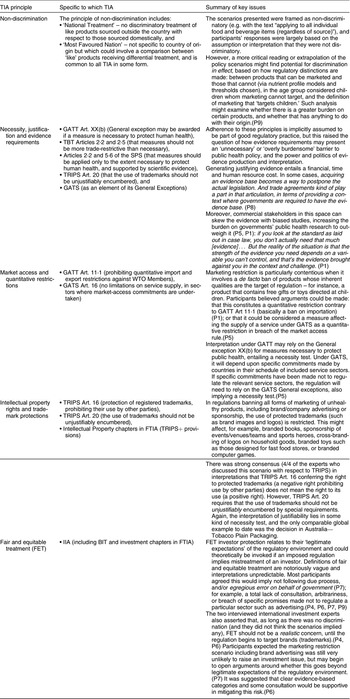

Participants mentioned a wide range of TIA with potential relevance, but their discussion consistently centred on similar principles common to most TIA: non-discrimination, necessity and justification with scientific evidence, market access requirements and quantitative restrictions, intellectual property rights and trademark protections and fair and equitable treatment of investors (Table 5)

Table 5 Technical TIA considerations for marketing restrictions identified by interview participants

Key policy design settings

Participant responses indicated that two main policy design factors that interact heavily with TIA-related policy space are the framing of objectives and regulatory distinctions drawn (i.e. the specified definitions, in particular those pertaining to which products are affected by the regulation, and which are not).

Framing of objectives

Framing of policy objectives is important in terms of showing necessity under the WTO Technical Barriers to Trade, justifiability under TRIPS, cause for General Exceptions under GATT and GATS, commitments to necessity or ‘proportionality’ common in many regional FTIA or non-arbitrariness (an aspect of FET) under IIA. Participants emphasised the importance of demonstrating the intervention’s link to the objective in the chain of causality for the health issue in question. The further the intervention is from the objective, along that chain, the harder it will be to establish the link due to the many external factors and forces that intervene along the way. For instance, if the desired end result is a reduction in prevalence of childhood obesity,

First of all you need to reduce exposure/power of marketing, then it needs to have some effect on either the purchase intention of children or the people who purchase foods for them, then that change in intention needs to translate to change in consumption, which needs to result in a healthier diet (for example fewer calories consumed, or less sugar, or whatever it is), and that healthier diet then needs to result in reduced prevalence of obesity. (P1)

Framing the regulatory objective in reference to more intermediate objectives would reduce this evidentiary burden.

Participants also indicated that a focus on protecting children in marketing restrictions (as opposed to restricting marketing to the public in general) may be more politically feasible (in terms of ethical arguments and political will), but must be matched with appropriate policy actions. A participant recounted that in Chile, for example, restriction of child-appealing advertising at bus stops, in parks and elsewhere other than in and around schools was not approved because this would be targeted to the general public as well – and therefore did not fit their definition of ‘child-directed,’(P2) highlighting one of the pitfalls of framing legislation around ‘child-directed’ or ‘child-targeted’ marketing rather than on power and exposure of children.

We expected that a rights-based approach might differ from one based on public health nutrition objectives. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), for example, includes commitments to protect children from information and material injurious to their well-being, including ‘misleading’ advertising. This treaty also recognises children as being ‘up to the age of 18.’ One legal expert participant acknowledged that pointing to commitments in an international human rights treaty such as the UNCRC, which is a separate/external treaty to those created under the WTO or regional or bilateral TIA, can help in establishing the legitimacy of a regulatory objective.(P7) How these separate treaties would interact in a trade or investment dispute is thus far untested. Nevertheless, in terms of the framing of objectives, if a policy is designed to fulfil a protected right, then the evidence needed to prove its effectiveness in achieving that right might not necessarily be health outcome-related. For instance, the objective could be a reduction in exposure to harmful commercial practices.

Regulatory distinctions

A common response was that, first and foremost, a policy restricting marketing of unhealthy food and beverages to children must be non-discriminatory between ‘like’ products in intent and in effect. A main challenge in policy design therefore lies in the definitions for regulatory distinctions (e.g. what is ‘persuasive,’ what is ‘targeting children’ or which products and brands are ‘unhealthy’). In other words, where do we draw the line between what is allowed to be marketed and what is not? To avoid challenges and delays, public health nutrition policymakers have to be very clear on these definitions from the beginning (which, as one expert involved in policy design pointed out, is often more difficult than it seems).(P3) They identified the definition of ‘child-appealing hooks’ as an area where further research is needed, as these are very challenging to define in terms of design elements – like shapes, colours and sound. This expert explained, ‘I think we just don’t know how to do it yet. That is part of the ambiguity of advertising: that we cannot describe it, however it’s clearly affecting the children, just in the way their brain is developed, and how they are very appealed-to by all these cues.’(P3) Studies have shown that even the nutrient profiling models used to distinguish ‘unhealthy’ or ‘high in’ products that should not be marketed to children can be contentious (in informal forums of debate, though notably never in a formal dispute), despite the WHO and its regional offices having established certain standards and definitions(Reference Labonté, Poon and Mulligan63–Reference Labonté, Poon and Gladanac65).

Because of the difficulties inherent to drawing regulatory distinctions, two participants speculated that comprehensive marketing restrictions (i.e. the later scenarios covering all forms of marketing of unhealthy food and beverages to children under 18, in all media) might have greater leeway in terms of non-discrimination, non-arbitrariness and FET.(P1, P7) On the other hand, broad marketing restrictions might entail more difficulty to prove necessity in proportionality to the objective,(P5) and may be less politically viable.

Contextual factors

Previous studies have established that contextual factors can have a moderating effect on the mechanisms through which TIA constrain policy space for restricting marketing of unhealthy food and beverages to children(Reference Garton, Thow and Swinburn29). Our findings suggest that domestic political/regulatory contexts, as well as actors/institutions involved at both domestic and international spheres, may constitute relevant contextual factors in this policy space.

Regulatory context

Analysis of interview data indicated three key factors relating to domestic regulatory contexts that influenced the potential for TIA to constrain policy space for marketing restrictions: domestic legal frameworks, the economy’s reliance on imported food and beverages and the state of available evidence (Table 6).

Table 6 Domestic regulatory context factors influencing policy space for marketing restrictions

The analysis of available policy space for regulatory marketing restrictions in any given country would therefore require context-specific legal analysis.

Actors and institutions

The actors and institutions active in the debates surrounding regulatory proposal, design and implementation appeared to influence policy space outcomes. Responses indicated that commercial stakeholders will be quick to raise concerns that marketing restrictions may violate existing TIA (specifically, in the ‘grey areas’ identified in Table 4). In the absence of voices knowledgeable about the detailed interpretative implications of trade and investment provisions, this could amount to regulatory chill. Several participants mentioned that a domestic Ministry of Business/Industry/Economy would be another initial opposing force to any regulation of marketing – with concerns around potential trade restrictiveness, investment agreements or even enforcement – through processes for internal regulatory vetting, including Regulatory Impact Assessments.(P3, P5, P8) Commercial stakeholders will usually have direct access to such government bodies to voice their concerns, potentially creating strong internal/domestic opposition to a marketing/advertising restriction policy. As evidenced in the scenarios, the more comprehensive the regulation, the more sectors and actors become involved – for example, from cable television providers, to supermarkets (for in-store point-of-sale marketing), to fast food services (in-product hooks and brands) and so on – and the greater their incentives become to oppose regulation. The strength of their influence will depend on how much power they represent within the domestic economy. The distribution of power (resources) and incentives was consistently mentioned as a key factor with respect to whether concerns or challenges are actually raised in trade or investment forums.

Discussion

Where and why do constraints arise and what can be done to mitigate risk?

Our findings suggest that governments interested in pursuing basic regulatory restrictions of marketing and advertising of unhealthy food and beverages to children, but wary of the potential repercussions in trade and investment forums, may proceed with reasonable confidence that well-designed (evidence-informed, non-discriminatory/non-arbitrary) marketing restriction regulations are unlikely to encounter any substantive constraints on the grounds of TIA, but would benefit from legal expertise. With the caveat that this in no way presents a legal analysis, our study suggests several features of strategic policy design within the health sector with potential to render regulations more robust and defensible against TIA-related challenges.

In terms of non-discrimination, a nutrient profile model can create a transparent and scientific basis to distinguish foods and beverage that cannot be marketed (a WHO-backed model will be the strongest). As for necessity and justification, basic national child overweight/obesity statistics can provide evidence of the need for regulation. Our analysis indicates that international evidence on how the power of and exposure to marketing influences food choices, as well as the international evidence showing ineffectiveness of voluntary codes, should provide sufficient justification for regulatory marketing restriction. Focusing restrictions on persuasive marketing techniques (e.g. featuring cartoons or other images, toys, giveaways) seems to be most easily justifiable but will require definition of persuasive elements (the definition of which will relate to the target age of the restrictions) and may in fact impede the implementation of more comprehensive restrictions that could significantly reduce children’s exposure to marketing. Restricting marketing to children under 18 might be justifiable (e.g. based on UNCRC commitments) though commercial stakeholders are likely to oppose, especially if there are other domestic age distinctions in place. Finally, if establishing time of day with restricted broadcast marketing, a watershed cut-off based on peak viewing times, for example between 07.00 to 21.00, appears to be increasingly supported by evidence(Reference Vandevijvere, Soupen and Swinburn66–Reference Mytton, Boyland and Adams69) and thus should be justifiable with local evidence of children’s peak viewing times.

Challenges associated with regulating all forms of product marketing

In the current study, we explored how a comprehensive regulatory restriction of all forms of marketing of unhealthy foods to children expands the service sectors affected and entails greater need for justification of ‘necessity.’ This greater evidentiary burden for regulating governments may present in itself a ‘procedural’ constraint to policy space. The greater potential impact on businesses also means greater incentive to fight proposed marketing regulations in any way possible.

Our study indicates that marketing restriction regulation is particularly contentious when it involves what might be interpreted as a de facto ban of products whose inherent qualities are the target of regulation. Prime examples of this are the Ferrero ‘Kinder Surprise’ chocolate egg that contains a toy and the MacDonald’s ‘Happy Meal’ targeted to children that usually includes free gifts or toys, which were among the products affected by marketing restrictions in Chile. Ferrero has argued that the toys inside ‘Kinder Sorpresa’ (as they are called in Chile) are ‘an essential and integral part of the product, which constitutes a single unit (…) The surprise is the essence itself of the chocolate egg, and in no case can be considered a hook for its consumption(Reference Krizanovic70).’ The company has stated it ‘reserves the right to activate national and international institutions to obtain a legal solution to this situation, which affects the reputation of one of its most popular and better-quality products(Reference Krizanovic70).’

Interestingly, Chile is not the only country to have banned ‘Kinder Surprise.’ The chocolate eggs have also been illegal in the USA because of a Department of Agriculture ban on importing food products with small parts due to choking hazard, and this US import restriction was never met with a trade dispute. And despite the threatening rhetoric, companies in Chile are adapting. By July 2016, Burger King had reportedly withdrawn all existing advertisements concerning children’s toys in Chile, ended all advertising to children under 14 and had ceased to deliver toys in all of their Chilean restaurants(Reference Carreno and Dolle36). MacDonald’s opted instead to reformulate the products contained in its ‘Happy Meal’ to continue to offer toys with it(Reference Carreno and Dolle36), resulting in healthier offerings in this children’s meal package.(P3)

Though it reportedly took 14 years (10 years of discussion, 4 to implement)(Reference Corvalan, Reyes and Garmendia71), this type of regulation covering all types of marketing in all media has been accomplished successfully in Chile. Corvalán et al. note that certain global regulatory developments that have taken place since (for example, the Pan American Health Organization’s nutrient profile model launched in 2015, which goes beyond Chile’s model to include non-caloric sweeteners, and action taken by other countries to restrict marketing of unhealthy foods to children) have further paved the way for governments wishing to implement such comprehensive regulatory child-directed marketing restrictions(Reference Corvalan, Reyes and Garmendia71).

Challenges associated with restricting brand marketing

The current study also explored some of the challenges in regulating food and beverage brand advertising, which appears to face the most potential TIA-related constraints to policy space with respect to intellectual property and trademark protections under the TRIPS Agreement, as well as FTIA (with TRIPS+ commitments) and IIA (Table 4). This is an important area of marketing regulation because the reach and appeal of unhealthy food and beverage brand advertising to children is strong. Children’s brand exposure at a young age means that brand recognition, preference and brand loyalty are developed early on(Reference Boyland and Tatlow-Golden6). Brands are known to advertise on social media platforms, such as Facebook, in ways that seek to engage adolescents and children (Reference Kelly, Freeman and King72). Tellingly, Australian children were found more likely to associate positive feelings (e.g. ‘cool, exciting, fun’) and personality traits (e.g. ‘popular, outgoing’) with unhealthy food brands, in a study that showed children’s alignment of brand characteristics with their own personality(Reference Kelly, Freeman and King72). And in the USA, pre-schoolers’ food brand recognition significantly predicted higher BMI in these children(Reference Harrison, Moorman and Peralta73). The power of brand advertising extends to low- and middle-income countries, where trans-national food and beverage logo recognition consistently and significantly related to preference for international products, like McDonald’s hamburgers and Coca Cola soft drinks, over domestic and local food and beverage options in a sample of children in Brazil, China, Nigeria, Pakistan and Russia(Reference Borzekowski and Pires74).

Our interview scenario also proposed regulating brand sponsorship, of sports events, for example, as there is strong evidence that ‘sports sponsorships with food and beverage companies often promote energy-dense, nutrient-poor products and while many of these promotions do not explicitly target youth, sports-related marketing affects food perceptions and preferences among youth(Reference Bragg, Roberto and Harris75).’ Athlete endorsements and food advertisements/product placement in sport video games are other areas of concern(Reference Bragg, Roberto and Harris75).

Participants expected there to be some challenges in this policy scenario relating to corporate trademark rights under TRIPS, and more importantly, IIA in relation to interpretations of FET and indirect expropriation. In-depth legal analyses would need to be carried out to assess the ‘legally available’ policy space for such a regulation in a given context. The existing Chilean regulation is the only comprehensive example to date, though it is limited in the area of restricting brand marketing – only going so far as restricting the use of strategies and imagery appealing to children: ‘for example, [a registered brand character] can be present, but cannot be doing any kind of physical activity, e.g. running or jumping or smiling or whatever.’(P2) And despite international evidence that major sports and cultural events have high overall numbers of youth viewership(Reference Bragg, Miller and Roberto76), the Chilean regulation was not able to regulate advertising at such events(Reference Corvalan, Reyes and Garmendia71). Nor could it regulate brand marketing activities linked to corporate social responsibility programmes.(P3)

The distinction of which brand advertising would not be allowed was a sticking point for participants. The Chilean marketing restriction regulation is interesting as it uses an exposure test and a power test to determine whether the marketing appeals to children(Reference Corvalan, Reyes and Garmendia71). We contend that, similarly, a 3-part test could be used to determine when brand advertising should be restricted: (1) is the brand/logo reasonably linked to unhealthy food or beverages? If yes, (2) is there expected exposure of children to this brand/logo or (3) does its representation have ‘power’ to attract children?

The case for bold policy making

Comprehensive marketing restrictions have the potential to shift cultural norms and preferences for food and beverages over time. For example, limited tobacco advertising bans first came about in the United States beginning in 1970, with little or no effect due to substitution of advertising to the remaining non-banned media(Reference Saffer and Chaloupka77). The Framework Convention on Tobacco Control now mandates comprehensive tobacco marketing bans (including point-of-sale promotion and display), and today some countries have, in effect, a ‘dark market’, significantly de-normalising tobacco use over the span of a generation(Reference Burton, Hoek and Nesbit78). Global marketing (facilitated by TIA) is one of the major drivers of global food and beverage consumption (alongside trade liberalisation and foreign direct investment)(Reference Friel, Schram and Townsend79). As such, restricting all forms of marketing of unhealthy food and beverages to children has the potential to create generational change in dietary preferences and norms, significantly constraining the ability of unhealthy food and beverage companies to sell their products to that demographic, and to shape their future preferences.

However, the challenge of setting regulatory distinctions means that policies may be overly vague, creating opportunities for commercial stakeholders to push back. Norway was one of the first countries to implement the WHO Set of Recommendations on the marketing of foods and non-alcoholic beverages to children, proposing regulation banning all marketing of unhealthy food and beverages ‘directed at’ children below 18 years in 2012(17). Accounts indicate that the initial regulation was vulnerable to attack by the food and beverage industry as it was ‘unduly broad’ (e.g. children were defined as being below 18 years of age), policy design left many ‘unanswered questions’ that opened the door to legal challenge and that non-compliance with European Economic Area Law was also a major critique(Reference Vaale-Hallberg23). Industry stakeholders claimed that the regulation created too much uncertainty over what kind of marketing would be legal(Reference Vaale-Hallberg24). Following such industry criticism, this became a self-regulatory regime administered by a Complaint Commission of the Food Industry, agreeing not to place marketing pressure on children below 13 years(Reference Vaale-Hallberg24), which has demonstrated questionable effectiveness in deciding which cases had breached the code(Reference Vaale-Hallberg25).

Chile’s Law of Food Labelling and Advertising is the most advanced national marketing restriction currently in place, with early evaluations showing significant reduction in children’s and adolescents’ exposure to ‘high in’ product advertising(Reference Dillman Carpentier, Correa and Reyes80,Reference Mediano Stoltze, Reyes and Smith Taillie81) , as well as a decline in household purchases of, and caloric consumption from ‘high-in’ beverages(Reference Smith Taillie, Reyes and Colchero82). A move to stricter ‘total ban’ advertising (rather than time slot) restrictions and lower nutrient thresholds in 2018 is expected to have eliminated the majority of children’s remaining product advertising exposure(Reference Dillman Carpentier, Correa and Reyes80). The industry responses to Chile’s measures suggest that, despite opening with threats to pursue challenges in international legal forums, they will toe the line when confronted with comprehensive marketing restriction regulations.

Finally, though Chile’s marketing restrictions represent a world-leading example, there are several remaining ‘loopholes’ precluding optimal protection of children from unhealthy food and beverage marketing(Reference Corvalan, Reyes and Garmendia71). This regulation should therefore be considered a baseline standard, but by no means a regulatory ‘ceiling.’ Governments need to have the policy space to go beyond this example if and when they see fit.

Implications for research, policy and practice

The implication of the current analysis, for policymakers, is that the substantive basis for trade-related concerns regarding the development of comprehensive regulatory marketing restrictions appears to be weak, though evidence and strategic policy design are important – especially for broader restrictions and those including brand marketing, which run the highest risk of encountering TIA-related constraints. There is, however, a higher risk of procedural constraints in the form of appeals to necessity/justification and lack of scientific evidence, market access requirements and quantitative restrictions, intellectual property rights and trademark protections and fair and equitable treatment of investors, creating delays and potentially derailment of the policy process.

Our findings highlight the importance of public health nutrition regulators having access to legal expertise with respect to international economic law, to provide an accurate picture of their ‘legally available’ policy space for marketing regulations(Reference Garde and Zrilič83). Especially, as the ‘everyday interpretive practices’ used by corporate stakeholders (including self-serving interpretations of TIA) to shape policy-makers’ perceptions of the legality of these regulations have been shown to be often at odds with the commonly-held interpretations of the (small) WTO legal expert community(Reference Dorlach and Mertenskotter37).

Due to participants’ emphasis on evidence requirements and challenges in defining what is to be regulated, the current analysis suggests the benefit of further research into what constitutes marketing targeting children (in terms of exposure and power-of-advertising dimensions) by looking at design elements (e.g. colours, shapes and sounds) more broadly and engagement designs (e.g. through digital media).

Strengths and limitations

A benefit of the vignette approach is that it provides many different angles from which to look at the research questions and allows the exploration of a variety of possible policy alternatives. As described by Swart, Raskin and Robinson, normative scenarios ‘represent organized attempts at evaluating the feasibility and consequences of trying to achieve certain desired outcomes or avoid the risks of undesirable ones(Reference Swart, Raskin and Robinson55).’ A key limitation of the current study was that there are few global examples of regulatory uptake for reference (essentially, only Chile). In addition, the global marketing and advertising landscape is rapidly changing (e.g. although the ‘old’ platforms are not well dealt with, there are new social media platforms constantly appearing), so it can be difficult to keep up with the implications and interactions with the (also dynamic) trade/investment space. Lastly, our exclusion of expert stakeholders from the food and beverage industry means that we may be missing additional perspectives, though the interviewed experts were asked how they expected industry stakeholders might respond to each scenario. Nevertheless, this series of interviews goes well beyond the limited literature in this area, adding to collective knowledge on policy space for mandatory restriction of unhealthy food and beverage marketing to children.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that regulatory marketing restrictions do run the risk of incurring challenges under WTO agreements and other FTIA. However, participants indicated a low likelihood of substantive legal challenges for most of the policy scenarios presented. Concerned policymakers should be aware of the difference between theoretical risk, threat of a challenge and realistic risk of initiation and/or loss of a formal dispute and design regulations accordingly. We recommend a bold and comprehensive approach to regulating food and beverage marketing environments, as risks can be reduced through strategic policy design. More inter-disciplinary work is needed exploring the intersection between food marketing regulations and international economic policy to address the uncertainties that may contribute to policy inertia.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution to study design and analysis of responses provided by Jane Kelsey and comments on draft versions provided by Amandine Garde and Fiona Sing. We also wish to thank each of the expert interview participants for contributing their valuable knowledge and perspectives to the current study. Financial support: The research was supported by a University of Auckland doctoral scholarship awarded to KG. The preparation of this manuscript was supported by a grant from the University of Auckland’s Performance Based Research Fund. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: All three authors collaborated in formulating the research questions and designing the study. KG carried out data collection. KG performed data analysis, with supervision from AMT and BS. KG drafted the manuscript, with BS and AMT providing substantial commentary. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee on 11 December 2017 for three years [reference number 020495]. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021001993