At the time of the present study (2009), Queensland Health provided a range of services for 4·33 million people through fifteen Health Service Districts across the state( 1 , 2 ). Queensland has an area of 1·73 million square kilometres, which makes it the second largest state in Australia and approximately seven times the size of Great Britain( 3 ). More than 50 % of Queensland's population lives in regional and remote areas outside the greater metropolitan area of Brisbane; it is the most decentralised state in Australia( 3 ). There were 67 947 full-time equivalent employees in Queensland Health, which represented approximately one-third of the Queensland public-sector workforce( 4 ).

Queensland Health has a clear leadership role in promoting healthy lifestyles throughout the state and this is increasingly important with the rising prevalence of lifestyle-related chronic disease( 5 ). The most recent data in Queensland indicate that at least 16 % of the total disease burden is due to measurable risk factors with dietary determinants (high blood pressure, high cholesterol, overweight and obesity, and low fruit and vegetable intake) and physical inactivity( 5 ). High BMI is now the leading cause of premature death and disability in the state, overtaking tobacco in 2007; measured data indicate that approximately one in three adults is overweight and one in four is obese( 5 ). There is also increasing evidence that consuming dietary patterns consistent with national evidence-based guidelines is associated with reduced morbidity and mortality( 6 ).

Public-sector settings such as health facilities and schools can provide a unique opportunity to model best practice food-supply policy interventions as part of government's leadership to promote healthy eating. In December 2005, the Queensland Minister for Health requested a review of the food and drink supply in food outlets and vending machines accessible by staff and the general public in Queensland Health facilities. Subsequent audits and mapping found that energy-dense, nutrient-poor (EDNP) foods and drinks were vastly over-represented (up to 80 % of displayed products) and recommendations were made to address this issue.

In 2007, Queensland became the first jurisdiction in Australia to introduce a state-wide policy approach to improve the food and drink supply in health facilities by developing A Better Choice Healthy Food and Drink Supply Strategy for Queensland Health Facilities (A Better Choice)( 7 ). The aim of A Better Choice is to increase the supply and promotion of healthy foods and drinks to staff, visitors and the general public in Queensland Health facilities, while limiting the supply and promotion of EDNP choices, thus making healthy choices the easier choices in this setting. The strategy applies to all areas where foods and drinks are provided including food outlets, staff dining rooms, vending machines, tea trolleys, coffee carts, catering at meetings or functions, leased premises, fundraising, promotion and advertising. These are referred to as ‘food supply areas’ throughout the present study. A Better Choice applies to all public health-care settings throughout the state including hospitals, community health centres, residential care facilities and office buildings. The strategy does not apply to foods and drinks that staff members bring from home or to in-patient, client and/or aged care residency meals.

A Better Choice classifies foods and drinks into three colour-coded categories: ‘green’ (best choices), ‘amber’ (choose carefully) and ‘red’ (limit), similar to methods described elsewhere( Reference Dick, Lee and Bright 8 ). Foods and drinks from the five ‘healthy’ food groups are in the ‘green’ category. Nutrient profiling based on the amounts of energy, saturated fat, sodium and fibre per serving or per 100 g is used to assess other foods and drinks to determine if they fit into the ‘amber’ or ‘red’ category. The ‘red’ category includes EDNP foods and drinks. The overall intent of the strategy is to increase healthier options to at least 80 % of foods and drinks on display and restrict less healthy or ‘red’ options to no more than 20 % of foods and drinks on display( 7 ). Only ‘green’ category foods or drinks are to be promoted or advertised( 7 ). A suite of hard-copy and web-based resources including practical toolkits, catering guidelines, product guides, recipes, promotional materials such as posters and postcards, and emailed policy directives were developed to assist strategy implementation and included specific requirements on the supply, display, advertising and placement of foods and drinks( 9 ). Implementation was supported by a high-level state-wide steering committee, a dedicated state-wide project officer and twenty-five volunteer A Better Choice district contact officers, who tended to be food-service managers, dietitians or nutritionists, and functioned as ‘champions’ for the strategy throughout the fifteen Health Service Districts.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, A Better Choice is the first comprehensive policy intervention to improve the food and drink supply in multiple public-sector health facilities. There is an absence of related research in the literature, but the concept aligns with the WHO Health Promoting Hospitals framework( Reference Whitehead 10 ). This views hospitals as institutions with the ability to influence the health and well-being of their clients, workforce and community and represents a shift from the provision of solely acute curative services to those that encompass the entire health and social continuum( Reference Whitehead 10 ). In this way, health facility settings differ from other workplace settings in their potential ability to broadly influence public food and health ‘culture’.

A Better Choice was introduced in September 2007 and became mandatory in all Queensland Health facilities in September 2008. The extent of strategy implementation was measured in May 2009. As an internal Queensland Health service-delivery quality improvement initiative, ethical approval was not required for the study.

Methods

Two data collection methods were used: an online survey of Queensland Health facility managers and telephone interviews with A Better Choice district contact officers. Self-reported survey methods were employed due to resourcing constraints related to the large number of facilities and staff involved across a vast geographic area, and also provided the opportunity to engage with key A Better Choice target groups throughout the state.

Survey of facility managers

The survey was directed to each facility manager who was responsible for the operational administration of an entire facility. A facility was defined as the services located on one geographical site. Facilities that did not provide any food service to Queensland Health staff or visitors were excluded. The final Queensland Health sample consisted of 278 facilities.

Full implementation of A Better Choice was defined as: ‘red’ foods and drinks limited to 20 % in food outlets, staff dining rooms, tea carts and coffee trolleys; ‘red’ foods and drinks removed totally from vending machines, catering and fundraising; and promotion and advertising of only ‘green’ foods and drinks. Responses to a series of questions assessing this definition were combined to determine an overall percentage of implementation in the different types of facilities. Categories were informed by the A Better Choice objectives and the range of responses described in evaluation of a similar initiative in Queensland schools( Reference Dick, Lee and Bright 8 ). Additional free-text options were provided for all responses and were the sole option to gather information on suggestions for future improvements.

The survey was administered electronically during a three-week period in May 2009. Scheduled reminders were forwarded periodically and major hospitals and facilities were prompted directly for response.

Quantitative results were analysed using the statistical software package SPSS 13·0. Frequencies and χ 2 tests were used to identify differences between groups; 95 % CI and P < 0·05 were used to conclude significant differences between groups.

Interviews with the A Better Choice district contact officers

Interviews of approximately 30 min duration were conducted by the A Better Choice state-wide project officer by telephone with A Better Choice district contact officers in each Health Service District during the same three-week period as the survey of facility managers. In larger Health Service Districts which had more than one A Better Choice district contact officer, more than one contact was interviewed. Interview questions were circulated one week in advance and covered the extent of strategy implementation, factors assisting implementation, barriers to implementation and additional support required. Qualitative responses were grouped by thematic analysis. Common themes and differences were identified and used to contextualise the results of the survey of facility managers.

Results

One hundred and thirty-four managers of 278 eligible facilities (48·2 %) responded to the online facility survey (Table 1). The sample comprised managers of thirty-eight metropolitan, fifty regional and thirty-four remote facilities. Twelve respondents did not identify location. Twenty-four of the twenty-five A Better Choice district contact officers participated (96 %); of these 45·5 % were catering/food-service managers and 33·6 % were dietitians or nutritionists and there was no significant difference between the professions of A Better Choice district contacts across geographical locations.

Table 1 Response rate for survey of facilities, Queensland, Australia, May 2009

Queensland Health facilities are not uniform in the types of food services they provide. The most common types of food supply areas reported were catering (66·4 %), vending machines (42·5 %) and staff dining rooms (38·8 %). Reported implementation rates for each food supply area were determined only for facilities where they were relevant.

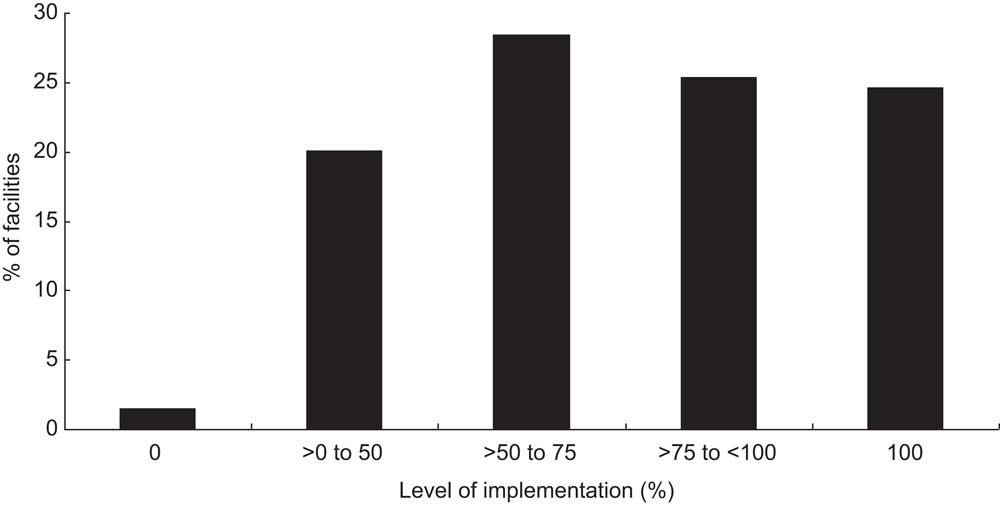

Of facility managers, 24·6 % reported full implementation of A Better Choice in all food supply areas in which it applied, 78·4 % reported implementation of more than half of the strategy requirements, 20·1 % reported implementation of up to half of the requirements and 1·5 % (two facility managers) reported that the strategy had not been implemented at all (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Reported level of implementation of A Better Choice requirements; 134 public sector-owned and -operated health facilities in Queensland, Australia, May 2009

There were no significant differences in reported implementation of A Better Choice based on facility location in metropolitan, regional or remote areas. However, there was a trend for more facility managers in regional or remote areas to report full or close to full implementation than metropolitan-area facility managers. There was also no significant difference based on facility type, but more community health-centre managers than hospital managers reported fully implementing the strategy, or being close to full implementation. Significantly more managers of small facilities (less than 100 staff; 36·6 %) reported fully implementing the strategy compared with managers of large facilities (100 or more staff; 9·8 %; χ 2 (4) = 21·9, P < 0·001).

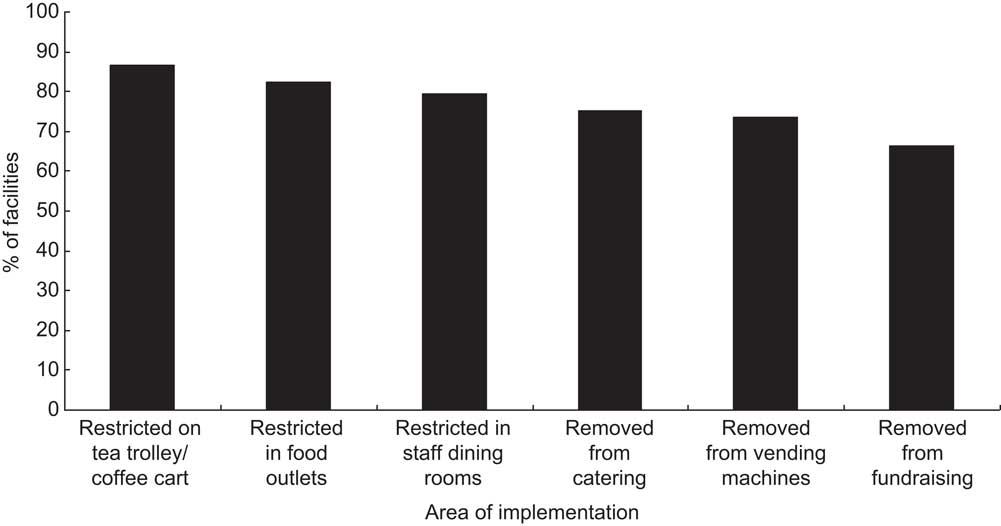

Restriction of ‘red’ foods and drinks to 20 % of displayed items in tea trolleys/coffee carts, food outlets and staff dining room was reported by 86·7 %, 82·4 % and 79·4 % of facility managers, respectively (Fig. 2). Complete removal of ‘red’ foods and drinks was reported by 75·2 % of facility managers in catering, 73·6 % in vending machines and 66·2 % in fundraising (Fig. 2). Some facility managers reported no removal of ‘red’ category foods and drinks at all from vending machines (12·4 %) or fundraising activities (12·3 %). Similar patterns of implementation were reported by the A Better Choice district contact officers.

Fig. 2 Reported compliance with the A Better Choice requirement to restrict and remove ‘red’ foods and drinks; 134 public sector-owned and -operated health facilities in Queensland, Australia, May 2009

Facility managers reported only advertising and promoting ‘green’ category foods and drinks in promotional stands (80·6 %), by cash registers (76·9 %), in cabinets or fridges (76·1 %), in point-of-sale promotions (75·4 %), on menu boards (73·1 %) and in vending machines (68·7 %). There were no significant differences in the number of facility managers reporting implementation of this part of the strategy across different areas.

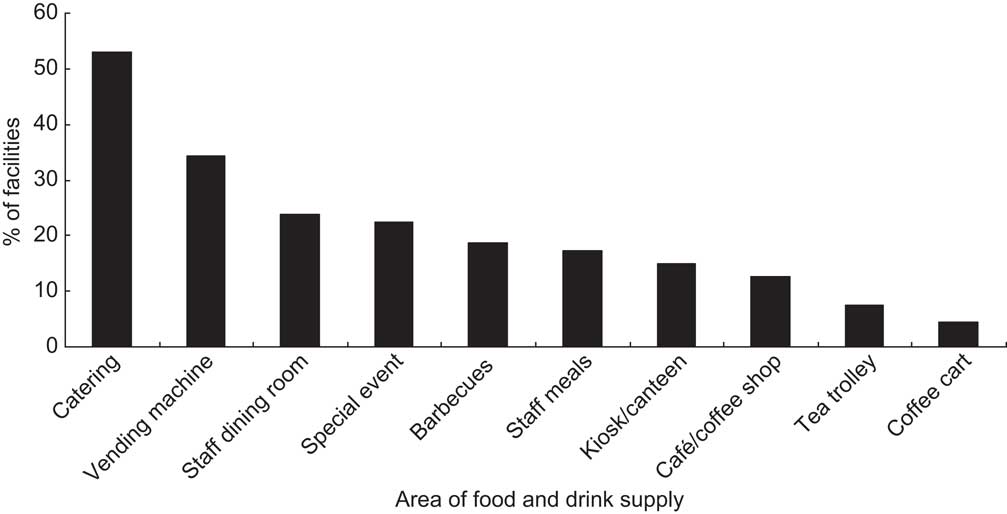

Reported improvement in food and drink supply, measured by increased availability of ‘green’ foods and drinks, was most common in catering (53·0 %), vending machines (34·3 %), staff dining rooms (23·9 %) and special events (22·4 %; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Reported increase in availability of ‘green’ products across different areas of the food and drink supply resulting from the A Better Choice requirement; 134 public sector-owned and -operated health facilities in Queensland, Australia, May 2009

Over 70 % of facility managers reported their staff found the catering guidelines (71·5 %) and posters (70·1 %) very useful or somewhat useful in aiding strategy implementation. Approximately half indicated that the toolkit (56·3 %), strategy document (54·3 %), brochures (50·9 %) and website (47·0 %) were very useful or somewhat useful.

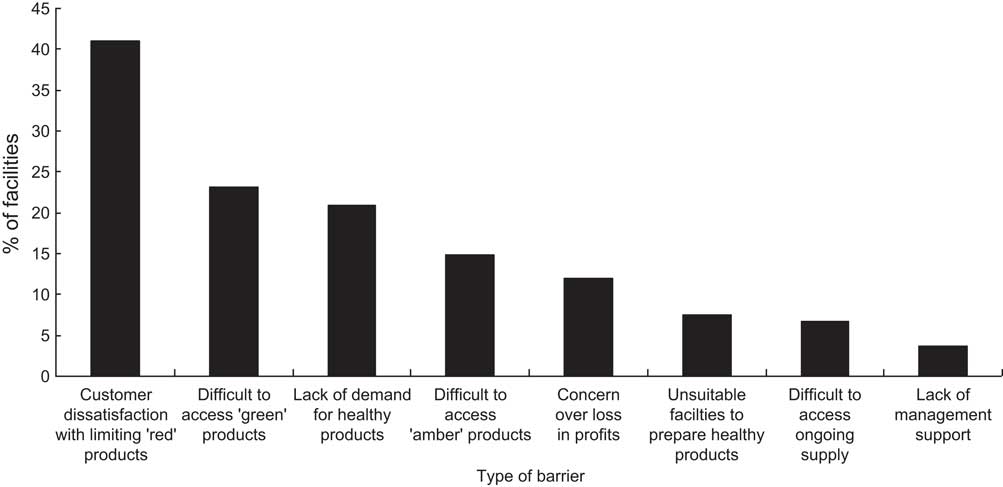

No barriers to implementation were reported by 39·7 % of facility managers; 60·3 % reported encountering barriers. Participants could nominate multiple responses. The most frequently reported barriers were perceived customer dissatisfaction with limitation of ‘red’ category foods and drinks (41·0 %), difficulty accessing suitable ‘green’ category products (23·1 %) and perceived lack of demand for healthy foods and drinks (20·9 %). Less commonly reported barriers were concern over loss of profit (11·9 %) and lack of management support (3·7 %; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Reported barriers encountered when implementing A Better Choice; 134 public sector-owned and -operated health facilities in Queensland, Australia, May 2009

Overall, 18·7 % of facility managers reported that no further support was required for implementation of A Better Choice. There were no significant differences in types of future support desired between facility managers who reported fully or not fully implementing A Better Choice. The most desired future support services for all facilities were more information on available products (47·8 %), materials to promote the strategy (46·3 %) and recipe ideas (41·8 %).

Discussion

Survey results suggested that most facilities had made changes to align with the requirements of A Better Choice. There were no significant differences in the degree of reported implementation across facility location or type, but small facilities were more likely than large facilities to have fully implemented the strategy. This finding may be explained by the complexity of strategy implementation in large facilities, which had more food supply areas, services and personnel, and faced greater communication demands in facilitating change. Small facilities tended to have fewer food supply areas requiring change and this was likely easier to address.

A Better Choice district contacts confirmed that most food outlets run by Queensland Health food services had changed to comply with A Better Choice. However, food outlets leased to a private provider or run by a volunteer group were slower and at times resistant to introducing the required changes. There were few reported examples of these providers embracing the strategy, but direct investigation with lease holders did not occur to substantiate claims.

Sixty per cent of facility managers reported experiencing barriers to implementation. Reported barriers were consistent with those described in a study of vending machines in Californian health facilities that reported difficulty sourcing healthier alternatives and financial concerns as challenges( Reference Lawrence, Boyle and Craypo 11 ). In a different setting, most schools do not appear to encounter overall losses of revenue after implementing nutrition policies, but more work is required to assess the financial impact of changes to food and drink supply policy in schools and other settings including health facilities( Reference Wharton, Long and Schwartz 12 ).

A Better Choice prohibits the supply of ‘red’ foods or drinks in catering that is paid for by Queensland Health. Catering was the most common food supply area across small and large facilities (66·4 %) and substantial improvements were reported by facility managers and district contacts in this area. The high rate of implementation may have been facilitated by the A Better Choice catering guidelines resource, which was reported as the most useful resource by facility managers. However, district contacts indicated that external catering was often non-compliant due to health management and staff being unaware of the guidelines or the nutrition criteria, choosing to ignore the guidelines or falsely believing that external catering was exempt.

A Better Choice requires removal of ‘red’ foods and drinks from vending machines to ensure that healthier choices are the easiest choices and to motivate the food industry to develop and reformulate healthier items suitable for vending. The survey of facility managers suggested high levels of implementation in vending machines generally. However, most A Better Choice district contact officers reported that improvements were substantially easier to make to drink vending machines than snack vending machines and that many facilities continued to stock ‘red’ snack products or removed snack vending machines altogether. Several regional and remote A Better Choice district contact officers reported difficulty in obtaining suppliers willing to comply with A Better Choice; changes to vending machine facing advertising was generally slower in regional and remote areas. This is likely to reflect the generally poorer services available in these areas compared with metropolitan areas.

Australian and international research has demonstrated the high levels at which EDNP foods and drinks are stocked in vending machines. A survey of 206 vending machines at train stations in Sydney found that 84 % of slots were stocked with EDNP foods and drinks( Reference Kelly, Flood and Bicego 13 ). A study of Californian health facilities found that only 25 % of drinks and 19 % of foods in vending machines adhered to comparable nutrition standards used in schools( Reference Lawrence, Boyle and Craypo 11 ). In a large workplace obesity-prevention programme across several American states, healthy vending machine policy was highlighted as a particularly challenging environmental intervention due to coordination with vendors, correct labelling and promotional pricing( Reference Goetzel, Baker and Short 14 ). An evaluation of the implementation of the Smart Choices Food and Drink Supply Strategy in Queensland Schools found high compliance in drink vending machines( Reference Dick, Lee and Bright 8 ) similar to the current study; however, Queensland schools generally do not provide snack vending machines.

Fundraising is another component of A Better Choice where ‘red’ foods and drinks must not be used. The use of ‘red’ fundraisers, such as chocolate or pie drives, is common because they are simple to organise and generate substantial profits. Fundraising compliant with A Better Choice had one of the lowest levels of implementation across facilities (66·2 %) and district contact officers reported that managers had not prioritised this issue. They also reported that fundraising was often run by volunteers who seemed more threatened by the strategy or more resistant to change. In the Queensland school setting, 80 % of school principals reported that the healthy food and drink policy had been implemented in school fundraising activities, but only 61 % of parents and citizens’ associations (groups that conduct school fundraising) felt that healthy fundraising could be financially viable( Reference Dick, Lee and Bright 8 ). The use of ‘red’ category foods and drinks has also been identified as an issue in fundraising( Reference Kelly, Baur and Bauman 15 ) and sponsorship( Reference Kelly, Baur and Bauman 16 ) in sports club settings. Despite the challenges associated with healthful fundraising, the range of healthy options is continuing to improve( Reference Franco and Welsby 17 – 19 ) and many commercial operators are now providing healthy alternatives( 20 , 21 ).

To increase implementation of A Better Choice, facility managers requested recipes, information about suitable products and promotional materials. As many of these materials had already been developed, greater promotion of existing A Better Choice resources is likely to be required. A Better Choice district contact officers also suggested additional targeted resources for external catering, snack vending machines and leased premises, reflecting the specific challenges in these areas. Responsibility for leading response to each recommendation was allocated to the state-wide strategy steering group, public affairs and marketing staff, or health facility workers. The mandatory nature of the A Better Choice strategy was expected to assist sustainability of the approach.

Parallels can be drawn between the intent of A Better Choice and other workplace nutrition interventions. These initiatives have traditionally targeted individual behaviour change to achieve improvements in health outcomes and much of the related research has been focused on reducing medical insurance costs in the USA( Reference Heinen and Darling 22 ). However, there is growing recognition that environmental policy and regulatory approaches may be more acceptable to workers and are likely to produce larger impacts on outcomes such as worker health and productivity( Reference Goetzel, Baker and Short 14 , Reference Devine, Nelson and Chin 23 ). Healthy cafeterias, vending machines and catering services as addressed by A Better Choice have been identified as important targets for improving food supply in workplaces( Reference Anderson, Quinn and Glanz 24 – Reference Engbers, van Poppel and Chin 26 ).

Queensland Health is a large employer in the state. At June 2011, the Queensland public sector as a proportion of the Queensland labour force had remained at about 10 % for approximately 10 years( 4 , 27 ). It has been argued that public-sector and health-care organisations should model best practices and that hospitals in particular should ensure a healthy food and drink supply for staff and visitors( Reference Heinen and Darling 22 ). Both public- and private-sector employers can apply nutritional standards for food outlets, vending machines and catering and to ensure that the supply and promotion of EDNP foods and drinks are reduced, just as smoking and alcohol are now restricted in most workplaces( Reference Heinen and Darling 22 ). The catering component of A Better Choice has now been adapted for use throughout the Queensland public sector( 28 ) and the A Better Choice state-wide project officer has been requested to supply strategy resource materials to other Queensland workplaces including remote mining camps.

Policy-led food supply interventions are an essential component of reversing the obesogenic drivers of the global obesity epidemic( Reference Gortmaker, Swinburn and Levy 29 ). Keys advantages of policy approaches include sustainability, broad reach and systemic nature, but political resistance and public reluctance may be greater than associated with traditional health education approaches( Reference Gortmaker, Swinburn and Levy 29 , Reference Swinburn, Sacks and Hall 30 ). Supporting healthy food-service policies in public- and private-sector organisations has been outlined as a core action for governments in reducing and preventing obesity( Reference Gortmaker, Swinburn and Levy 29 ). In addition, the evidence base related to obesity prevention requires expansion beyond randomised controlled trials to encompass evaluation of natural experiments, policy and cost saving( Reference Gortmaker, Swinburn and Levy 29 , Reference Swinburn, Sacks and Hall 30 ). A Better Choice is one example of evidence translation of public policy approaches to improve the food and drink supply in a complex, real-world setting.

Limitations

A major limitation is that self-reported results are more subjective than recorded observations. While a degree of concordance between the reports of facilities managers who were responsible for implementation of the policy and the A Better Choice district contact officers who had a greater advocacy role as ‘champions’ of the policy increased confidence in the results, the high risk of positive bias remains. Further assessment of the level of implementation of A Better Choice for quality improvement and/or evaluation purposes should be conducted by observational audits on a regular basis.

It is not known if the facilities of non-responding managers differed significantly in strategy implementation compared with those who responded. Consequently, results may not be generalisable to all Queensland Health facilities. Implementation of A Better Choice in large hospitals potentially benefited more staff and community members and these sites were actively followed up to ensure a survey response. Hence the sample of large facilities was more representative of these facilities, which may have introduced a bias in the reporting compared with small facilities. The response rate was lower for small facilities and it is possible that the managers of small facilities achieving full implementation were more likely to respond.

Although responsible for the implementation of A Better Choice in their facilities, managers may not always have been the ideal employee to complete the facility survey as they were often removed from front-line strategy implementation, especially in large facilities. However, addressing the survey to the facility manager may have increased awareness of their accountability in ensuring full implementation of A Better Choice throughout their facility.

Conclusion

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, A Better Choice is the first reported effort to apply a food supply policy to address all areas where foods and drinks are provided and promoted in multiple public-sector health facilities, including food outlets, staff dining rooms, vending machines, catering at meetings and functions, tea trolleys, coffee carts, leased premises, fundraising, promotion and advertising. A Better Choice sought both to increase the supply and promotion of healthy choices and to decrease the supply and promotion of EDNP foods and drinks. For practical and operational reasons policy implementation was assessed by self-report, but in the future objective audits of the food and drink supply should be conducted to address limitations in methodology.

Nevertheless, the level of consistency between reported policy implementation by the facility managers and the A Better Choice district contact officers supports the notion that improvements were achieved in the supply of foods and drinks in food outlets, staff dining rooms, internal catering, tea trolleys, coffee carts and drink vending machines in many public-sector health facilities after a 9-month policy implementation period. Reported results also suggest that further work is required to achieve higher levels of policy implementation in snack vending machines, external catering, leased premises and fundraising activities.

The present study has demonstrated that, despite many challenges, policy approaches to improve the food and drink supply can be implemented successfully in public-sector health facilities, although results may be limited in some food supply areas. A Better Choice may provide a model for improved food supply in other health and workplace settings.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: This activity was funded by Queensland Health. Staff from Queensland Health contributed to the study design and conduct, interpretation of the findings and preparation of the manuscript. Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest to report. Ethics: Ethics approval was not required. Authors’ contributions: J.M. contributed to the strategy implementation and evaluation and led the preparation of this paper; A.L. managed the strategy development, implementation and evaluation; N.O. led the strategy development and implementation; and RE led the strategy implementation and evaluation. All authors approved the final manuscript. Acknowledgements: The authors thank all Queensland Health staff and external partners who contributed to the development and implementation of A Better Choice and the Queensland Chief Health Officer, Dr Jeannette Young, for her leadership role.