Food security refers to whether households can consistently afford and have physical and economic access to sufficiently healthy food at all times(1). Approximately 12 % of households in the UK reported being food insecure between 2021 and 22(2). In the United States of America (USA), 10·2 % of households and 12·5 % of households with children were food insecure in 2021(3). Figures from Canada were slightly higher at 18·4 % in 2021(4). Data from public surveys in the UK showed that food insecurity in households with children increased from 12·1 % in January 2022 to 23·4 % in June 2023(5).

Food aid, where food is free or greatly reduced in price, in high-income countries is usually provided by charitable organisations. The continuing financial crisis and global food inflation are leading to rising demand for food aid(6). In the USA, 49 million people required food aid in 2022(7). In the UK, people using food banks increased by 177 % from March 2019 to 2020(8). More recently, almost 3 million food parcels were distributed by the largest group of food banks between 1st April 2022 and 31st March 2023, an increase of 37 % from the same period in the previous year(9). The trend is reflected in Canada, with almost 1·5 million visits to food banks between March 2021 and March 2022, an increase of 15 % from the previous year(10). The pressures of the economy are also affecting food aid, with food banks facing challenges of declining donations, increasing numbers of people requiring support and sustaining their volunteer workforce(11). Research has identified barriers and limitations of food banks, such as limited opening hours, inadequate food provisions(Reference Oldroyd, Eskandari and Pratt12) and feelings of shame and embarrassment among users(Reference van der Horst, Pascucci and Bol13,Reference Garthwaite14) . Interventions providing emergency access to food are subsequently evolving to try and better serve users’ needs.

The need for food aid could be a consequence of inadequate welfare assistance resulting in insufficient resources to purchase food or short-term ‘shocks’ such as loss of income due to job loss, illness or disability. Low-income households are particularly vulnerable to food insecurity(Reference Leete and Bania15–Reference Loopstra, Reeves and Tarasuk18). Evidence shows people experiencing food insecurity are more likely to experience unemployment, low income, be of non-white ethnicities, have low educational qualifications, be lone-parent households and have a disability(Reference Loopstra, Reeves and Tarasuk18–Reference Yau, White and Hammond21). Food bank use, food insecurity, poverty and adverse health outcomes are closely related(Reference Garthwaite, Collins and Bambra22). Food insecurity is associated with an increased risk of chronic diseases such as CVD(Reference Philip, Baransi and Shahar23), type 2 diabetes and poor mental health(Reference Thomas, Lammert and Beverly24,Reference Barker, Halliday and Mak25) .

Household food insecurity is complex as one or all family members can experience food insecurity at different severities with a range of implications. Adults in food-insecure households have been observed to skip or reduce their meals to ‘shield’ children from the effects of hunger and undernourishment leading to a detrimental effect on the adult’s diet quality(Reference Hanson and Connor26). Children living in food-insecure households have a poor-quality diet(Reference Keenan, Christiansen and Hardman27) with low consumption of fruits and vegetables(Reference Pilgrim, Barker and Jackson28). Low fruit and vegetable consumption are risk factors for CVD, cancer and all-cause mortality(Reference Aune, Giovannucci and Boffetta29). Children in food-insecure households also have a greater risk of mental health problems(Reference Darling, Fahrenkamp and Wilson30,Reference Melchior, Chastang and Falissard31) , but shielding has been observed to improve mental health outcomes in children(Reference Ovenell, Azevedo Da Silva and Elgar32). Associations have been found between food insecurity and behavioural problems, poor academic performance and emotional problems(Reference Shankar, Chung and Frank33). Subsequently, food insecurity and associated poor-quality diet and mental health problems can place a major financial strain on the healthcare system in treating short-term and chronic conditions leading to a public health crisis.

Few studies have examined the effectiveness of multiple types of food aid interventions, and existing studies predominantly focus on outcomes in adults receiving food aid(Reference Oldroyd, Eskandari and Pratt12,Reference An, Wang and Liu34,Reference Oronce, Miake-Lye and Begashaw35) . To address this gap, we broadened the interventions to cover various types of food aid and included outcomes in children. Therefore, this review aims to systematically review and narratively synthesise studies investigating the impact of food aid interventions in households with children (≤ 18 years) in high-income countries. The first objective is to investigate the effectiveness of food aid interventions in reducing food insecurity. The second objective is to investigate how food aid interventions impact diet quality, mental health and/or weight status in adults and children within a household.

Methods

This systematic review is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines(Reference Page, McKenzie and Bossuyt36). A scoping search was initially conducted in the Web of Science to identify keywords commonly describing food aid interventions. Synonyms for the category’s population, food aid, food insecurity, diet quality, mental health and weight status were identified. Synonyms were combined with ‘OR’ and categories with ‘AND’ shown in Table 1, creating a comprehensive search. A library specialist assisted with developing the search strategy. A systematic electronic search was conducted on 09th July 2022 using the databases Web of Science and EBSCOhost for MEDLINE, CINAHL and PsycINFO.

Table 1 Search strategy

Eligibility criteria

The search was limited to studies published in English from 1st January 2008 to 9th July 2022 to ensure up-to-date interventions are included. The global financial crisis of 2007–2008 resulted in widespread job losses, a substantial rise in food insecurity and an increased demand for food aid in high-income countries(Reference Belcher and Tice37,Reference Davis and Geiger38) . Food aid has since remained a key resource for people living in poverty or facing a short-term financial crisis(Reference Goodwin39,Reference Lambie-Mumford, Silvasti, Lambie-Mumford and Silvasti40) . Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in Table 2.

Table 2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review

Screening process

Results were exported into Rayyan(Reference Ouzzani, Hammady and Fedorowicz41), an online software screening tool, and duplicates were removed. Title and abstract screening was performed by a single reviewer (CS); however, a random 10 % sample was independently screened by a second reviewer (ET). An agreement of 94·1 % was achieved between the two reviewers, and discrepant titles were included in the abstract screening. CS reviewed the remaining 90 % of titles. The same process was followed for abstract screening with 91 % agreement, and discrepant abstracts were included for full-text screening. CS and ET independently screened all remaining full-text papers against the inclusion criteria. The agreement was 64 %. CS and ET discussed the eight studies which were discrepant and reached a consensus for 4 papers. A third reviewer (NZ) was consulted regarding eligibility for the remaining 4 discrepant papers.

Data extraction

CS extracted the data from the full-text papers; however, a random selection of 20 % from the final full-text papers was selected for second reviewer extraction. CS and ET independently extracted data for these papers using a modified version of the Cochrane Collaboration data extraction form(42). CS and ET reviewed the information to ensure consistency. Data extracted included authors, year, country, study design, population, sample size, description of intervention, data collection method and outcomes. For statistically significant outcomes, CI or p-values were reported.

Quality assessment and risk of bias assessment

CS and ET independently conducted quality assessment and risk of bias for all full-text papers using the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Assessment tool(43). Studies were categorised as good, fair or poor. A ‘good’ study would have a low risk of bias.

Results

The search identified 10 394 records, of which 3414 were duplicates. Titles of 6980 records were screened, and of these, 278 abstracts were screened. Full-texts of 25 papers were screened and 9 papers were included in this review (Fig. 1). Due to the heterogeneity of the studies, a meta-analysis could not be performed and the results are presented as a narrative review.

Fig. 1 PRISMA flow chart detailing the selection process

Characteristics of included studies

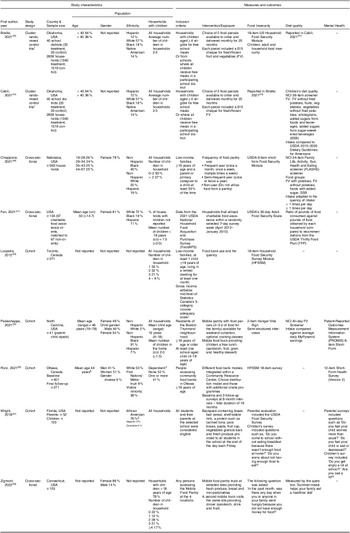

Study designs include one cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT), which reported relevant outcomes in two separate papers(Reference Cabili, Briefel and Forrestal44,Reference Briefel, Chojnacki and Gabor45) , three cross-sectional(Reference Chiappone, Gribben and Calloway46–Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48) and four cohort(Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk49–Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) studies (Table 3). Two studies were based in Canada(Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk49,Reference Rizvi, Wasfi and Enns50) and seven in the USA(Reference Cabili, Briefel and Forrestal44–Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48,Reference Wright and Epps51,Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) .

Table 3 Characteristics of included studies

Food parcels could be ordered online or via telephone. Choice of 5 food parcels containing shelf-stable foods, including 6 protein-rich items, 2 dairy items, 4 grain foods, 4 cans of fruit, 12 cans of vegetables, recipes and nutrition education handouts. All eligible children were allowed 1 parcel each. Chickasaw Nation Nutrition Service nutritionists selected items based on the quality of their nutritional content, knowledge about what Chickasaw Nation families eat and communication with Chickasaw families. The food parcel, including the $15 check, was valued at $53 per eligible child(Reference Cabili, Briefel and Forrestal44,Reference Briefel, Chojnacki and Gabor45) .

* The RCT studies are the same intervention with food security reported by Briefel et al. (Reference Briefel, Chojnacki and Gabor45) and children’s diet quality by Cabili et al. (Reference Cabili, Briefel and Forrestal44)

† Statistics Canada’s 5-category income adequacy scale: ≤ $29 999, $39 999 or $59 999 if household 1 or 2 people, 3 or 4 people or 5+ people, respectively.

‡ Dependents include children or adult dependents.

§ Ethnicity data shown are for the whole school population (n 496) and not the sample population. Socio-demographic sample data was not collected as the researchers were concerned about the privacy and confidentiality of the participants. The data indicate the ethnicity mix of the school.

The study population varied widely within the studies. Generally, females were the main respondents(Reference Chiappone, Gribben and Calloway46–Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48,Reference Rizvi, Wasfi and Enns50) . Three studies were in ethnic minority groups, predominantly non-Hispanic Black populations(Reference Chiappone, Gribben and Calloway46,Reference Wright and Epps51,Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) . Four were in mostly non-Hispanic White populations(Reference Cabili, Briefel and Forrestal44,Reference Briefel, Chojnacki and Gabor45,Reference Fan, Gundersen and Baylis47,Reference Rizvi, Wasfi and Enns50) . Two studies(Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48,Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk49) did not collect individual ethnicity data; however, one stated the residents in the target neighbourhoods were mostly Black or Hispanic(Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48). The populations were mostly from low-income areas(Reference Cabili, Briefel and Forrestal44–Reference Chiappone, Gribben and Calloway46,Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48,Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk49,Reference Wright and Epps51,Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) and/or from neighbourhoods where most children were eligible for free school meals(Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48,Reference Wright and Epps51) .

Two studies evaluated a mobile pantry combined with providing a free meal for children; one operated on weekends(Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) and the other during summer holidays(Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48). One study evaluated a programme where children were provided free food provisions in a backpack during the school term(Reference Wright and Epps51). Four studies assessed food bank models/use(Reference Chiappone, Gribben and Calloway46,Reference Fan, Gundersen and Baylis47,Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk49,Reference Rizvi, Wasfi and Enns50) . The RCT analysed a free food parcel home delivery intervention(Reference Cabili, Briefel and Forrestal44,Reference Briefel, Chojnacki and Gabor45) .

The parcel delivery(Reference Cabili, Briefel and Forrestal44,Reference Briefel, Chojnacki and Gabor45) and backpack(Reference Wright and Epps51) interventions were primarily aimed at children. Two programmes(Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48,Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) aimed to benefit the whole household by locating a mobile pantry and food truck giving free meals to children in the same location. Four studies investigated food aid use, two included households comprising any mix of individuals(Reference Chiappone, Gribben and Calloway46,Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk49) , and two only investigated participants with children(Reference Fan, Gundersen and Baylis47,Reference Rizvi, Wasfi and Enns50) .

Food insecurity was reported as a quantitative outcome in seven studies(Reference Briefel, Chojnacki and Gabor45–Reference Wright and Epps51). One study(Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) collected qualitative data from 20 participants using semi-structured interviews to investigate the impact of food insecurity on families and perceptions of the effectiveness of the programme. Data were collected using validated questionnaires; two studies used the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) 18-item Household Food Security Module(Reference Briefel, Chojnacki and Gabor45,Reference Wright and Epps51) , one used the 6-item Short-Form Household Food Security Module(Reference Chiappone, Gribben and Calloway46) and one utilised the USDA 30-day Food Security Scale(Reference Chiappone, Gribben and Calloway46). Zigmont et al.(Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48) used one specific question from the USDA 18-item Household Food Security Module to assess food insecurity. The two studies from Canada utilised the 18-item Household Food Security Survey Module(Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk49,Reference Rizvi, Wasfi and Enns50) , an adapted version of the USDA 18-item Household Food Security Module which has been used routinely by the Canadian government(53).

Dietary data were collected in five studies(Reference Cabili, Briefel and Forrestal44,Reference Chiappone, Gribben and Calloway46–Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48,Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) . Two different screeners from the National Cancer Institute were used in two separate studies: 24-item fruit and vegetable screener(Reference Chiappone, Gribben and Calloway46) and an all-day fruit and vegetable screener(Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52). Another study collected food group data consisting of fruit and vegetables, foods with added sugar and sugar-sweetened beverages and compared intake to USDA dietary guidelines(Reference Cabili, Briefel and Forrestal44). One cross-sectional study(Reference Fan, Gundersen and Baylis47) used data from the 2012 National Food Acquisition and Purchase Survey (FoodAPS). The researchers compared the ratio of the USDA Thrifty Food Plan recommended pounds of consumption and actual pounds of foods obtained by the household for each food group. The Thrifty Food Plan is designed by the USDA to meet the nutritional requirements of a family of four, integrating USDA healthy eating guidelines and food preferences and is achieved at the lowest cost(54). One study(Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48) collected limited dietary data, asking respondents whether they strongly agree, agree, disagree or strongly disagree if ‘Summer meals help my family eat a healthier diet.’ The figures were presented alongside other socio-demographic characteristics of the sample by food security status.

Mental health outcomes were measured in three studies(Reference Rizvi, Wasfi and Enns50–Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52). Two studies used validated questionnaires: Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System 8-item Anxiety Short-Form to assess parental anxiety(Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) and the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey, version 2 to evaluate the mental health of the adult respondents(Reference Rizvi, Wasfi and Enns50). One study assessed mental health and anxiety by providing a short questionnaire to both children and parents asking about the children’s mental health and anxiety(Reference Wright and Epps51).

Quality assessment

There was high heterogeneity between the study populations, with various measures and reporting of diet quality and mental health outcomes. The RCT(Reference Cabili, Briefel and Forrestal44,Reference Briefel, Chojnacki and Gabor45) was the only study rated ‘good’. Blinding was not possible as the intervention involved participants ordering a food parcel. Randomisation of households was carried out to reduce confounding factors. There was low attrition of participants, ensuring the statistical power of the results was reliable. Four studies(Reference Chiappone, Gribben and Calloway46,Reference Fan, Gundersen and Baylis47,Reference Rizvi, Wasfi and Enns50,Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) were rated as ‘fair’. Of these, two studies(Reference Chiappone, Gribben and Calloway46,Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) reported dietary intakes using validated surveys. One(Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) collected baseline and follow-up data after three to six months, with the other study(Reference Chiappone, Gribben and Calloway46) collecting data at one point in time only during visits to community centres where participants were recruited. One study analysed household food purchasing data from a nationally representative survey of US households(Reference Fan, Gundersen and Baylis47).

Food security data for all studies were collected using a validated survey. Data from all studies were self-report, thereby introducing recall(Reference Althubaiti55) and response bias(Reference Schoeller, Bandini and Dietz56,Reference Burrows, Ho and Rollo57) which can lead to over- or underestimating the true effectiveness of the interventions.

There are some limitations of the dietary data collection for all the studies. Diet surveys were collected retrospectively, and therefore liable to information bias, and used either a 30-day(Reference Cabili, Briefel and Forrestal44,Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) or one-week(Reference Chiappone, Gribben and Calloway46,Reference Fan, Gundersen and Baylis47) reference period for analysis. Two studies(Reference Cabili, Briefel and Forrestal44,Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) investigating children’s diet quality asked the parent/caregiver to report their child’s food consumption. Another source of information bias is that parents/caregivers may not be present for all of their children’s eating occasions, leading to incomplete or inaccurate data.

In one study(Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48), while dietary intake data were not collected, participants were asked whether the intervention helped their family eat a healthier diet. The question is too broad to elicit accurate data for determining diet quality, which limits the validity of these findings.

Dietary surveys were carried out using various methods across the studies, including interviews in-person(Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48,Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) , via the phone(Reference Cabili, Briefel and Forrestal44) or both(Reference Fan, Gundersen and Baylis47). These methods risk introducing social desirability bias, where participants may over-report the consumption of healthier foods, particularly with sensitive discussions regarding their children’s dietary habits.

Two studies(Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk49,Reference Wright and Epps51) did not provide socio-demographic data on the sample population. Low response rates (Reference Wright and Epps51), high attrition(Reference Rizvi, Wasfi and Enns50,Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) and lack of completion of follow-up surveys(Reference Wright and Epps51,Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) were key limitations. Due to high attrition in the Ottawa study(Reference Rizvi, Wasfi and Enns50), the researchers reduced the study period from 24 to 18 months.

Convenience sampling was mostly used, which has a high risk of selection bias. Participants were recruited door-to-door(Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk49,Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) , whilst waiting in line at food banks(Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48,Reference Rizvi, Wasfi and Enns50) , from community venues(Reference Chiappone, Gribben and Calloway46) and from parents expressing an interest in participating in the school backpack programme(Reference Wright and Epps51).

Summary of findings

The summary of findings for all included studies is presented in Table 4. In some studies, not all participants used food aid, and therefore, only the subsample that used food aid is included in the tables.

Table 4 Summary of findings for included studies

* Food pantry use categories: semi-frequent user – once or twice a year and some months but not every month; frequent user – once a month, once a week and multiple times a week(Reference Chiappone, Gribben and Calloway46).

† Attributes used to match CFA clients to non-clients included age, sex, marital status, race/ethnicity, education, household size, number of children in the household, number of seniors in the household, whether the household lived in rural areas, monthly household income before tax, whether the household was food insecure.

Food insecurity

Three studies showed food insecurity prevalence was reduced in households where food aid was utilised(Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48,Reference Rizvi, Wasfi and Enns50,Reference Wright and Epps51) . Results from the cluster RCT(Reference Briefel, Chojnacki and Gabor45) with 2859 participants show adult food insecurity significantly reduced by 2·8 % points (P = 0·002, 95 % CI: –4·8, –0·9) and household food insecurity by 2·4 % points (P = 0·003, 95 % CI: –4·1, –0·6) at the first 12-month follow-up. However, no significant difference remained in adult or household food insecurity at the final 18-month follow-up.

The Ottawa cohort(Reference Rizvi, Wasfi and Enns50) included only food bank users (n 401). Food bank use of more than three times in the preceding three months decreased over the four waves of data collection: baseline (52 %), 6-month (51 %), 12-month (42 %) and 18-month (40 %). At the end of 18 months, food-secure participants increased from 11 % to 18 %, and severely food insecure decreased from 39 % to 25 %. However, accessing food banks did not appear to be effective as participants with more than three food bank visits remained severely food insecure (47 %), moderately food insecure (50 %) and marginally food insecure (46 %). There were significant reductions in food insecurity by visiting food banks in a community resource centre providing additional health, social and welfare services (β 0·59, CI: 0·99, 0·19, P < 0·01) and choice-based models in which users choose their food items (β 0·53, CI: 0·89, 0·17, P < 0·01)(Reference Rizvi, Wasfi and Enns50).

In Loopstra and Tarasuk’s cohort of 371 low-income families in Toronto, only 23 % of families used a food bank(Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk49). Odds of using a food bank at the 12-month follow-up increased with severity of food insecurity; moderately food insecure (OR 3·21, 95 % CI: 1·26, 8·18) and severely food insecure (OR 3·75, 95 % CI: 1·18, 11·90). Among participants using a food bank at baseline and follow-up (n 54), 41 % were severely food insecure and remained so at follow-up, with only 13 % no longer reporting severe food insecurity. Of those who no longer used a food bank at follow-up (n 31), only 7 % reported no longer being severely food insecure and 13 % reported being newly food insecure.

Evaluation of a backpack programme at a public school in Florida (n 120 students, 52 parents)(Reference Wright and Epps51) showed a small but non-significant trend in improved parental food insecurity reduced from 2·63 ± 0·166 at the beginning of the school year to 1·81 ± 0·180 at the end of the school year, P = 0·081). Qualitative feedback supports the finding as parents stated more food was available for the family.

Cross-sectional survey responses from 153 individuals participating in a summer mobile pantry and supper programme in New Haven, USA(Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48) demonstrated positive results. Sixty-eight per cent of participants attended with children, of whom 65 % reported it is generally more difficult to feed their family during the summer holidays when children do not receive school meals. The programme proved modestly effective as 37 % of participants agreed it was easier to feed their family compared to 26 % who disagreed. Forty-five per cent agreed they could obtain sufficient food from the programme. However, 13 % of food-insecure participants agreed the programme makes it easier to feed their family compared to 24 % who were food secure. A smaller proportion of food-insecure participants (17 %) reported obtaining enough food compared to 27 % of food-secure respondents.

Diet quality

Diet quality was better for households using some form of food aid(Reference Cabili, Briefel and Forrestal44,Reference Fan, Gundersen and Baylis47,Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) . For instance, children receiving the food parcel delivery in the RCT(Reference Cabili, Briefel and Forrestal44) significantly increased daily fruit and vegetable consumption, 0·1-cup equivalents compared to the control group (P < 0·001, 95 % CI: 0·06, 0·13) and 0·06-ounce equivalent increase in wholegrains (P < 0·001, 95 % CI: 0·04, 0·08). Additionally, frequency of mean daily consumption significantly increased for fruits (fresh, frozen, canned) (P < 0·001, 95 % CI: 0·06, 0·14), vegetables (P = 0·048, 95 % CI: 0·00, 0·06), brown rice and cooked wholegrains (P < 0·001, 95 % CI: 0·01, 0·02). This represented a 5 % increase in fruit and vegetable and 9 % increase in whole grain consumption for households receiving the food parcel.

The weekend mobile pantry and lunch programme(Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) resulted in a non-significant increase in fruit and vegetable intake. Baseline daily serving of total fruit and vegetables (including dried beans and tomato and vegetable soup) was 3·39 (sd ± 9·02) and at follow-up was 3·88 (sd ± 9·44), P = 0·41.

Charitable food assistance clients obtained significantly more non-starchy vegetables (0·16 [sd: ±0·03] v. 0·08 [sd: ±0·02], P = 0·018) than non-clients(Reference Fan, Gundersen and Baylis47). A non-significant increase in obtaining meat and beans (0·57 [sd: ±0·11] v. 0·34 [sd: ±0·06], P = 0·051) was also observed between clients and non-clients. Clients obtained 28 % of their food from charitable food aid which suggests that food aid utilisation is likely responsible for providing the additional vegetables, meat and beans.

One cross-sectional(Reference Chiappone, Gribben and Calloway46) study of 563 food pantry users in Nebraska observed a negative impact of pantry access on diet quality. Greater odds of consuming foods with added sugar ≥ 1 per day were reported in frequent (OR 2·14, 95 % CI: 1·33, 3·44) and semi-frequent (OR 1·57, 95 % CI: 1·00, 2·46) food pantry users compared to non-users(Reference Chiappone, Gribben and Calloway46). However, this represents food items obtained from all sources, not only the food pantry, indicating participants’ overall dietary intake. In the mobile pantry with supper programme(Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48), participants were asked if the programme helped them eat healthier, with 43 % agreeing. However, only 15 % of food-insecure respondents agree the programme helps them eat healthier, compared to 27 % of food-secure participants. Dietary intake data was not collected; therefore, it cannot be deduced which foods improved diet quality or establish any statistically significant improvements.

Mental health

Three cohort studies reported mental health outcomes(Reference Rizvi, Wasfi and Enns50–Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52). A small increase in mean perceived mental health scores measured using the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey from 40·2 ± 11·3 at baseline to 41·6 ± 11·9 at the end of the 18-month study period (P < 0·001) was reported in the Ottawa cohort(Reference Rizvi, Wasfi and Enns50), demonstrating an improvement. The scores are measured on a continuous scale from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better perceived mental health. Lower mean mental health scores were observed with greater severity of food insecurity. Participants who were marginally food insecure scored 44·5 ± 12·2, moderately food insecure 39·6 ± 11·4 and severely food insecure 35·8 ± 10·8. The mobile pantry and weekend lunch programme(Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) reported no change in parental mean anxiety scores from baseline (50·0 ± 9·85) to follow-up (50·7 ± 8·19, P = 0·51). A score of 50 in the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System 8-item Anxiety Short-Form reflects a mean anxiety score for the general population and indicates no depression. Survey responses from parents in the backpack programme at a public school in Florida (n 120 students, 52 parents)(Reference Wright and Epps51) reported greater child anxiety and sadness at the end of the programme but the children did not report any sadness or anger.

Many programmes reported that parents expressed relief(Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48,Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) from financial pressure and obtained more fruit and vegetables. Children reported being grateful, enjoying healthier foods and trying new foods(Reference Cabili, Briefel and Forrestal44,Reference Briefel, Chojnacki and Gabor45,Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48,Reference Wright and Epps51) . Parents were appreciative of the healthier food items(Reference Cabili, Briefel and Forrestal44,Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48,Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) , convenience(Reference Cabili, Briefel and Forrestal44,Reference Briefel, Chojnacki and Gabor45,Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48) and relief knowing food aid was available locally(Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48,Reference Wright and Epps51,Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) . However, people did not take full advantage of the food aid. In the RCT(Reference Cabili, Briefel and Forrestal44), only 65 % ordered a parcel in one of the intervention months. The mobile pantry and children’s lunch lost 50 % of their sample due to attrition(Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52). Sixteen per cent of participants in the other mobile pantry programme stated they would visit the pantry less than once a week(Reference Zigmont, Tomczak and Bromage48). The longitudinal analysis(Reference Rizvi, Wasfi and Enns50) also lost 67 % of their baseline sample who accessed food banks. It is unclear why some participants did not fully engage with the programmes or access food banks even though positive feedback was provided.

Discussion

Food aid use was associated with improved food security and diet quality in some of the included studies. Food bank models offering additional support such as community programmes, health and social services, cooking classes and a free meal for children, client-choice-based models and programmes providing convenient access were more likely to be associated with improved food security and diet quality. Parents also reported that feeding their families with sufficient and healthy foods was easier after accessing food aid.

The findings from this review show that greater severity and persistent food insecurity(Reference Chiappone, Gribben and Calloway46,Reference Fan, Gundersen and Baylis47,Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk49,Reference Rizvi, Wasfi and Enns50) were often experienced by more frequent food aid users. Likely, a proportion of people accessing food aid in the cross-sectional studies were experiencing food insecurity when surveyed, hence the requirement for food aid assistance. This is a limitation of the included cross-sectional studies, and with this risk of possible reverse causality, the results must be interpreted cautiously.

A qualitative follow-up 6 months after the original study completion of 11 participants found that 10 continued to regularly rely on food banks and stated quality, choice and insufficient quantities of food remained a problem(Reference Rizvi, Enns and Gergyek58). This aligns with research showing that food banks minimally alleviate food insecurity(Reference Bazerghi, McKay and Dunn59) with many people relying on them long-term(Reference Caspi, Davey and Barsness60,Reference Loopstra61) . Food banks were not intended to be a long-term intervention; however, they are becoming entrenched in the food environment(Reference Thompson, Smith and Cummins62).

Established barriers to accessing food banks include physical access, distance and lack of transport, short opening hours and long queues(Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk49,Reference Dave, Thompson and Svendsen-Sanchez63) . Additional obstacles include not meeting personal food preferences, cultural or religious requirements, receiving insufficient or poor-quality food(Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk49,Reference Rizvi, Enns and Gergyek58,Reference Enns, Rizvi and Quinn64–Reference Kihlstroma, Long and Himmelgreen66) . Qualitative research consistently highlights feelings of shame, embarrassment, powerlessness and stigma which negatively impact the mental health of individuals and their families(Reference van der Horst, Pascucci and Bol13,Reference Garthwaite14,Reference Middleton, Mehta and McNaughton67,Reference Douglas, Sapko and Kiezebrink68) . In response to these challenges, some traditional food bank models have evolved to mitigate the associated mental health impacts. Food bank clients describe the choice of food items as a priority(Reference Caspi, Davey and Barsness60), and interventions offering choice give greater autonomy to clients leading to improved self-esteem, a sense of control and dignity(Reference Enns, Rizvi and Quinn64). Such positive mental health outcomes have been reported in the Ottawa cohort(Reference Rizvi, Wasfi and Enns50) in this review, and improved self-sufficiency and reductions in food insecurity are supported in other studies investigating choice-base models and targeted referral services(Reference Martin, Wu and Wolff69,Reference Martin, Colantonio and Picho70) .

Parents have been shown to shield children from food insecurity by reducing their food intake to provide food for their children, thereby mitigating negative mental health impacts for their children(Reference Shinwell and Defeyter17,Reference Hanson and Connor26,Reference Ovenell, Azevedo Da Silva and Elgar32) . In turn, parents experience emotional distress that can be detrimental to their mental health(Reference Hevesi, Downey and Harvey71). Only one study in this review surveyed both children and adults pre- and post-intervention(Reference Wright and Epps51). Parental anxiety had a small improvement, but children did not report any improvement in their mental health. This may suggest that overcoming barriers such as physical access, distance, transport and no queuing to receive food aid may also be an effective way to reach households with children and improve mental health.

Results for diet quality were inconsistent. Studies have repeatedly observed diet quality to be low in food bank users(Reference Eicher-Miller72,Reference Marmash, Ha and Sakaki73) , with low intakes of fruit and vegetables, dairy(Reference Hanson and Connor26,Reference Simmet, Depa and Tinnemann74) and increased intake of added sugar(Reference Marmash, Ha and Sakaki75,Reference Hutchinson and Tarasuk76) . Only one study in this review observed more frequent food pantry use and increased consumption of foods with added sugar(Reference Chiappone, Gribben and Calloway46). Research shows that food parcels are often inadequate with insufficient quantities of nutrient-dense food(Reference Oldroyd, Eskandari and Pratt12,Reference Simmet, Depa and Tinnemann77,Reference Fallaize, Newlove and White78) , likely due to reliance on donations. Food insecurity is independently associated with a poor-quality diet and poor health(Reference Yau, White and Hammond21,Reference Hanson and Connor26,Reference Kirkpatrick and Tarasuk79) . Food aid clients disproportionally face difficulties achieving a healthy diet and are at increased risk of chronic disease(Reference Garthwaite, Collins and Bambra22).

One effective intervention identified in this review was the food parcel delivery(Reference Cabili, Briefel and Forrestal44). A more recent study investigating bi-weekly fresh fruit and vegetable home delivery with virtual nutrition education in the USA(Reference Fischer, Bodrick and Mackey80) did not report significant improvements in food insecurity or fruit and vegetable intake. Both studies included recipe cards and nutritional education as additional resources for participants. The difference in the effectiveness could be that the intervention in this review provided five parcels to select from, potentially giving clients a sense of dignity and improved self-esteem(Reference Kihlstroma, Long and Himmelgreen66). Notably, children liked the novelty of receiving a parcel which some referred to as a present and were more willing to try new foods. A systematic review investigating food pantry interventions in the USA corroborates that choice-based models and nutrition education were the most effective at improving food insecurity and diet quality(Reference An, Wang and Liu34).

One study(Reference Palakshappa, Tam and Montez52) included in this review provided optional cooking skills classes at a local church or community centre which participants enjoyed and stated they learnt new skills. However, many did not use the classes due to schedules or family commitments. This suggests that educational material can be effective; however, the delivery should be either at home, that is online or at the point of food parcel collection for convenience.

An alternative and convenient method to collecting parcels is giving children a backpack with food items during school hours. Although this review found no favourable outcomes, another study reported children had more energy, improved academic performance, school grades and shared food with other family members(Reference Laquatra, Vick and Poole81). Reliable and robust studies investigating the impact of such backpack programmes are still needed as the effectiveness of food insecurity and diet quality is mixed and limited(Reference Hanson and Connor82–Reference Walch and Holland84). Although all children in the school received the backpack, another review observed some children feel ashamed or stigmatised at receiving backpacks(Reference Fram and Frongillo83). Not only could this approach lead to negative mental health impacts for children, it can also diminish the effectiveness in settings where a smaller proportion of the school population is eligible. It could be an effective targeted option in schools or areas where most children are eligible for a backpack.

Accessing food aid may temporarily alleviate or reduce the severity of food insecurity. However, other factors such as employment and income likely have a more substantial impact on reducing food insecurity(Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk16,Reference Shinwell and Defeyter17) . Improving employment and income would be a more effective long-term strategy to reduce the need for long-term reliance on food aid(Reference Smith and Thompson85).

Studies on households with children, including parent’s and children’s individual perspectives, are limited. Therefore, outcomes in children and adults should be evaluated to develop more effective and targeted interventions to benefit the whole household. Due to the differing political and welfare systems in different countries, the limited evidence from the UK and Europe warrants further research to gauge the effectiveness of current interventions in these geographic and diverse socio-demographic populations.

Strengths and limitations

This review is the first to systematically review quantitative outcomes of how food aid interventions impact households with children. The screening process, quality assessment and data extraction included a second independent reviewer. A comprehensive search strategy was conducted using a wide range of terms describing food aid from the literature enabling relevant studies to be identified.

Limitations of this review include only studies published in English. Therefore, effective or novel interventions published in other languages could not be assessed. Generalisability of the results is limited due to the heterogeneity of the populations, variability of interventions and outcome measures. The majority of studies did not include a comparator or control group. Consequently, it cannot be inferred the outcomes improved as a direct result of the food aid interventions. With the exception of one study, all other included studies were observational designs and thus causality cannot be inferred.

The heterogeneity of reported outcomes did not allow for statistical analysis or a meta-analysis to compare the effectiveness of the interventions. Only two studies were rated as good, suggesting more high-quality studies are needed to provide robust and reliable evidence of the effectiveness of food aid interventions.

Implications for public health

Food banks rely on donations from the public and surplus food from commercial organisations such as food retailers and restaurants. With the current global rise in the cost of living and inflation, people are less able to donate. Commercial organisations are potentially reducing costs by limiting surplus food leading to fewer donations. Additionally, the economic crisis will likely increase the number of people who require food aid; therefore, immediate action is necessary to support vulnerable households.

The links between poverty, low income and adverse health outcomes, that is the socioeconomic gradient of health, are well researched. The global economic crisis will continue to constrain household budgets. Vulnerable households are at risk of sliding further down the gradient and likely to become food insecure. Consequently, a greater proportion of the population risk consuming a nutritionally inadequate diet leading to a rise in chronic disease. The resultant healthcare costs of managing chronic disease will place additional pressure on health services. Increased poverty and long-term ill health are major public health concerns.

Whilst out of the scope of this review, some of the issues, namely low income, material and social deprivation, and health inequalities require considerably more upstream action. The government must acknowledge the unintended regular and long-term use of food banks, which include less healthy food than households may choose to purchase. Current policies and the welfare system are not meeting the needs of these individuals and families. There is an urgent need to implement changes in the welfare system and to find a way to support charitable food assistance organisations to provide short- to medium-term relief to current and future users or increase welfare benefit payments to increase food security for lower-income households(86).

Conclusion

Households continue to experience persistent food insecurity. However, models where clients can choose items, food banks in community centres offering additional support and convenient ways to receive food items demonstrated improvements in food insecurity and diet quality. Choice and support should be incorporated into food aid interventions in the absence of increased value of benefits which would support food security.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

The Wessex DIET study which this review formed part of is supported by the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration Wessex. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. The views and opinions expressed in this protocol are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Authorship

The research question was formulated and refined by D. S., N. A. A., N. Z. and C. S. The search was carried out by C. S. Screening, data extraction and quality assessment were carried out by C. S. and E. T. Discrepancies were resolved with N. Z. C. S. interpreted and synthesised the results with review from all other authors. C. S. wrote the first draft of the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics of human subject participation

Not applicable.