‘Unhealthy diets and physical inactivity are key risk factors for the major non communicable diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and diabetes.’

Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health, 2004

The lifestyle of individuals is very vulnerable to negative influences during adolescence, which is a crucial period of life when both major physical and psychological changes occur. Overall, there is a worldwide trend to adopt unhealthy behaviours( Reference Mazzarella and Pizzuti 1 , Reference Moreno, Rodriguez and Fleta 2 ); for instance, both the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), a WHO collaborative cross-national survey in European countries( Reference Currie, Nic Gabhainn and Godeau 3 ), and the Youth Risk Behaviour Surveillance System (YRBSS) in the USA( 4 ) have indicated that skipping breakfast, low consumption of fruit and vegetables, high consumption of junk foods and increased sedentary activities are often observed in adolescents of both genders.

The risks associated with unhealthy behaviours related to diet and physical activity begin in childhood and build up throughout life( 5 ). During adolescence, diet may affect health status also in the short term, for instance by increasing adiposity and negatively affecting cardiovascular risk factors( Reference Davis, Gance-Cleveland and Hassink 6 ); similarly, sedentary behaviours and low physical activity are associated with excess body fat, hypertension and high cholesterol levels( Reference Freedman, Dietz and Srinivasan 7 ).

Meeting health recommendations is expected to improve quality of life and to reduce the incidence of chronic diseases( Reference Aarnio 8 – Reference Kavey, Daniels and Lauer 10 ). Adolescents’ behaviours can be modified through a number of different strategies, for example communication campaigns and educational counselling( Reference Evans, Uhrig and Davis 11 ) following the most common national( 12 ) and international recommendations( 9 , 13 , 14 ) such as: (i) having breakfast; (ii) consumption of ≥5 servings of fruit and vegetables/d; (iii) consumption of ≥3 servings of milk/yoghurt daily; (iv) practice of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) for ≥60 min/d; and (v) limiting watching television (TV) to <2 h/d.

Notwithstanding, little is known in adolescents about either the clustering of dietary and physical activity behaviours or their effects on health outcomes( Reference McKenna, Taylor and Marks 15 , Reference Sanchez, Norman and Sallis 16 ) and surrogate end points. Among the latter, waist circumference (WC), a widely recognized marker of abdominal fat, is of particular practical interest because it is a predictor of metabolic and cardiovascular risks in adults and children( Reference Takami, Takeda and Hayashi 17 , Reference Savva, Tornaritis and Sedvva 18 ). As a matter of fact, WC and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) are both able to identify children with a higher metabolic and cardiovascular risk better than BMI-for-age or skinfold thickness( Reference Saelens, Seeley and van Schaick 19 – Reference Ashwell, Gunn and Gibson 21 ). While WC has been shown to be related to each healthy behaviour( Reference Alexander, Ventura and Spruijt-Metz 22 – Reference Martinez-Gomez, Rey-López and Chillón 25 ), no data are available regarding the association with clustered behaviours.

The major aims of the present study were to: (i) evaluate the prevalence of meeting recommendations for breakfast consumption, fruit and vegetable intake, milk/yoghurt consumption, MVPA levels and TV watching in a sample of adolescents from southern Italy; and (ii) assess in these adolescents the association between meeting health recommendations and abdominal adiposity. As a secondary end point, junk snack food consumption and its correlation with unhealthy behaviours were assessed.

Methods

Participants

The study population was derived from a cluster-randomized sample of high-school students attending the second and third grade, participating in a study on the prevention of eating disorders (DiCAEv) in adolescence. That study took place in three high schools in Naples (Campania region, Italy) between March 2007 and December 2009. The sample included Caucasian individuals belonging to all socio-economic classes (according to parental educational level) and was representative of the school population of the Campania region( Reference Mazzarella and Pizzuti 1 ). The adolescents’ parents or guardians were fully informed about the objectives and methods of the study and signed a consent form. Also the adolescents provided their written assent. Study procedures were carried out according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by academic and scholastic institution boards. Inclusion criteria were: (i) age between 14 and 17 years and (ii) consent to participate. Six hundred and eighty-seven adolescents were available to be recruited, but only 550 families gave their consent to participate in the study (80 %); adolescents with missing data on any of the independent variables considered in the survey were excluded (n 72). Therefore a total of 478 adolescents were finally evaluated (participation rate 86·9 %).

Measures

Anthropometry

A portable scale (Seca model 813, Hamburg, Germany) was used to measure weight to the nearest 0·1 kg, with shoes and heavy clothing removed. Height was measured to the nearest 0·1 cm using a portable stadiometer (Seca model 220). BMI (kg/m2) was calculated as body weight divided by the square of height. WC was measured at the narrowest point between the lower costal border and the iliac crest using a non-extensible steel tape (Seca model 200). Measures of height and waist were taken three times and the mean value was considered for data analysis. WHtR, a marker of abdominal fat deposition independent of age( Reference Ashwell, Gunn and Gibson 21 ), was calculated and the cut-point of ≥0·5 was used to identify adolescents with high abdominal adiposity( Reference Ashwell and Hieh 26 ). Categories of overweight (OW) and obesity (OB) were defined according to the BMI thresholds proposed by Cole et al. ( Reference Cole, Bellizzi and Flegal 27 ) for international comparisons, where the cut-off points for OW and OB are smooth sex-specific BMI centiles, constructed to match the values of 25·0 and 30·0 kg/m2, respectively, at age 18 years. Parental education level was considered as a proxy index of socio-economic status.

Dietary intake

In the present study, the consumption of breakfast (d/week) and that of four food items (fruit, vegetables, milk, yoghurt products) was explored. Usual dietary intake was assessed through an FFQ administered by interview by two trained nutritionists. For each food item, respondents were asked to indicate the frequency of consumption per day, per week or per month. Never and seldom were also included and considered as ‘zero’. All reported numbers were converted to daily frequency (servings/d). The daily intake for each food group (fruit and vegetables; milk and yoghurt) was calculated by summing up the frequency of consumption of fruit plus vegetables or milk plus yoghurt. In the same way, the consumption (servings/d) of snack foods rich in fat and/or added sugars, such as crisps or chocolate bars (defined as ‘junk snack foods’( Reference Anderson and Patterson 28 )), was also assessed. Participants were classified as meeting each dietary recommendation when they consumed: breakfast on ≥6 d/week, ≥5 servings of fruit and vegetables/d and ≥3 servings of milk/yoghurt daily( 9 , 12 , 13 ).

Physical activity

The modified long version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), as proposed by the HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence) study( Reference Craig, Marshall and Sjostrom 29 , Reference Hagströmer, Bergman and De Bourdeaudhuij 30 ) and adapted into Italian according to the IPAQ committee guidelines (http://www.ipaq.ki.se/cultural.htm), was administered by trained operators. The questionnaire for adolescents focuses on four domains: (i) school-related physical activity (including activity during physical education classes and breaks); (ii) transportation; (iii) housework; and (iv) leisure time. The housework domain included only one question (compared with three in the original IPAQ) about physical activities in the garden or at home. For each of the four domains, the number of days per week and the number of physical activity periods per day (≥10 min of physical activity) were recorded. Outcome measures were average minutes of walking, moderate or vigorous activities per day; the sum of moderate and vigorous activities was computed to obtain minutes of MVPA per day. Participants were classified as meeting physical activity recommendations if they performed MVPA for ≥60 min/d( 14 ).

Sedentary behaviours

The study also included a questionnaire assessment regarding daily hours spent in TV watching and computer or video game use. Average time spent watching TV (h/d) was used as a proxy for unhealthy sedentary behaviour because it is considered an important determinant of OW in adolescence compared with video game and computer use( Reference Rey-López, Vicente-Rodríguez and Biosca 31 ). Participants were classified as meeting the specific recommendation if they limited TV watching to <2 h/d( 14 ).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical software package version 18·0. The level of significance was set at P < 0·05. Variables were not normally distributed. Descriptive statistics, including medians, 25th and 75th percentiles, frequencies and percentages, were used to describe demographic and anthropometric characteristics of participants as well as healthy lifestyle behaviours. The non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare differences in age, height, weight, BMI, WC and WHtR between genders. The Spearman's rank correlation test was performed to evaluate whether healthy lifestyle behaviours and junk snack food consumption correlated with each other. The χ 2 test was used to compare proportions for parental education levels or selected health behaviours between genders. The χ 2 test for trend was used for analysis of proportions between a binary variable (OW/OB status; WHtR ≥ 0·5) and an ordered categorical variable (number of risk factors). Finally, binary logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate associations of each of the selected health recommendations with WHtR, controlling for age and gender.

Results

Demographic and anthropometric characteristics

Demographic and anthropometric characteristics of the adolescents are shown in Table 1. No difference in BMI was found between genders, while WC and WHtR were higher in boys than girls. OW prevalence was higher in boys than girls (29·9 % v. 19·7 %, respectively; P < 0·01), while OB prevalence did not differ between genders (9·8 % v. 6·9 %, respectively; P = 0·2). WHtR was ≥0·5 in 23·8 % of boys and 10·3 % of girls (P < 0·01).

Table 1 Demographic and anthropometric characteristics of the study population: adolescents aged 14–17 years (n 478) attending three high schools in Naples, Italy, March 2007 to December 2009

WC, waist circumference; WHtR, waist-to-height ratio.

The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the differences in median values between genders, while the χ 2 test was used to compare the proportion of parental education levels between genders.

*Statistical significance was taken as P < 0·05.

Meeting health recommendations

As median (25th–75th percentile) values, adolescents had breakfast on 7 (1–7) d/week, consumed 1·6 (1·0–2·7) servings of fruit and vegetables/d, consumed 1·0 (0·3–1·0) servings of milk/yoghurt daily, reported 22·9 (11·1–45·7) min of MVPA/d and spent 2·0 (1·0–2·5) h watching TV/d.

The proportion of adolescents meeting each of the selected health recommendations is shown in Table 2; 55·4 % for having breakfast, 2·9 % for eating fruit and vegetables, 1·9 % for milk/yoghurt consumption 13·6 % for performing MVPA and 46·3 % for TV watching. No differences between genders were found, except that having breakfast and milk/yoghurt consumption that were slightly more frequent in boys. More than 65 % of adolescents ate ≥1 serving of junk snack foods/d (median 1·14, 25th–75th percentile 0·71–1·86), with no gender difference. The number of health recommendations met by the same individual was also considered (Table 3). About 21 % of the sample did not meet any health recommendation, while only about 5 % fulfilled three recommendations, and <0·5 % fulfilled four recommendations. No gender differences were found (Table 3).

Table 2 Proportion of the study population who met each of the selected health recommendations: adolescents aged 14–17 years (n 478) attending three high schools in Naples, Italy, March 2007 to December 2009

MPVA, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; TV, television.

The χ 2 test was used to compare the proportions meeting selected health recommendations between genders.

*Statistical significance was taken as P < 0·05.

Table 3 Distribution of meeting multiple health recommendations in the study population: adolescents aged 14–17 years (n 478) attending three high schools in Naples, Italy, March 2007 to December 2009

Finally, healthy lifestyle behaviours and junk snack food consumption were correlated with each other; only significant results are reported here. There was a positive association between having breakfast and eating fruit and vegetables (r = 0·113, P < 0·02); both of these eating behaviours were positively correlated with milk/yoghurt consumption (r = 0·523, P < 0·001 and r = 0·134, P < 0·004, respectively) and negatively correlated with eating junk snack foods (r = −0·173, P < 0·001 and r = −0·179, P < 0·001, respectively). Watching TV was negatively correlated with having breakfast (r = −0·093, P < 0·05) and eating fruit and vegetables (r = −0·154, P < 0·01), while it was positively correlated with eating junk snack foods (r = 0·186, P < 0·001). Total time spent in sedentary behaviours was negatively correlated with eating fruit and vegetables (r = −0·181, P < 0·001) and positively correlated with eating junk snack foods (r = 0·244, P < 0·001).

Relationships between meeting health recommendations and abdominal adiposity

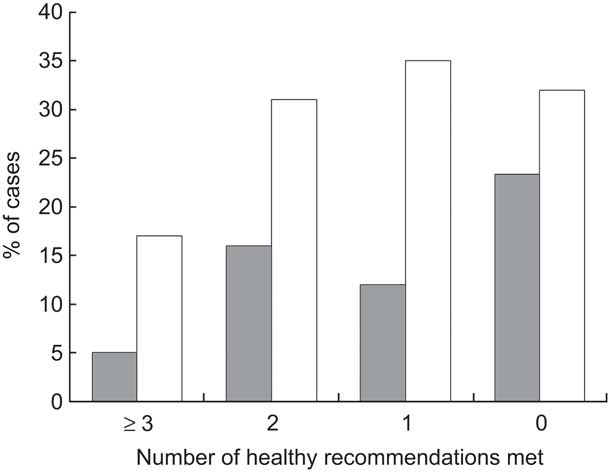

When the association between WHtR as outcome variable with each of the healthy lifestyle behaviours as independent variables was considered, the only positive relationship emerged with TV watching (r = 0·118, P < 0·05). On the other hand, as the number of healthy recommendations met decreased, the percentage of adolescents with abdominal adiposity rose (Fig. 1, P < 0·002, χ 2 for trend). The trend was not significant for the prevalence of OW/OB (P = 0·329). Having regular breakfast, performing ≥60 min of MVPA/d and watching TV for <2 h/d represented the most frequent cluster of healthy lifestyle behaviours (89 %) in adolescents with WHtR < 0·5. Finally, the logistic regression model demonstrated that male gender (OR 2·560, 95 % CI 1·338, 4·892; P < 0·005) and watching TV for ≥2 h/d (OR 2·260, 95 % CI 1·154, 4·427; P < 0·02) were the only independent variables positively associated with high WHtR values.

Fig. 1 Percentage of cases with abdominal adiposity (waist-to-height ratio >0·5; ![]() ) or overweight/obesity (

) or overweight/obesity (![]() ) in the different categories of multiple healthy recommendations met among adolescents aged 14–17 years (n 478) attending three high schools in Naples, Italy, March 2007 to December 2009. The χ

2 test for trend was used for the statistical analysis of proportions: as the number of healthy recommendations met decreased, the percentage of adolescents with abdominal adiposity rose (P < 0·002), while the trend was not significant for overweight/obesity (P = 0·329)

) in the different categories of multiple healthy recommendations met among adolescents aged 14–17 years (n 478) attending three high schools in Naples, Italy, March 2007 to December 2009. The χ

2 test for trend was used for the statistical analysis of proportions: as the number of healthy recommendations met decreased, the percentage of adolescents with abdominal adiposity rose (P < 0·002), while the trend was not significant for overweight/obesity (P = 0·329)

Discussion

The main results of the present study indicated that: adolescents living in Campania region only seldom meet health recommendations on diet and physical activity; healthy behaviours are correlated with each other; and there is a positive association of male gender and TV watching with abdominal adiposity.

Meeting health recommendations

The present study has considered main dietary and physical activity recommendations as important determinants of present and future health( Reference Edwards, Mauch and Winkelman 32 – Reference Crespo, Smit and Troiano 35 ). First, the proportion of adolescents meeting each of the recommendations was evaluated. Skipping breakfast has been related in adolescence to irregular pattern of meals and junk food consumption( Reference Hoyland, Dye and Lawton 36 – Reference Affenito, Thompson and Barton 38 ), and it is also associated with an increased risk of excess body fat( Reference Szajewska and Ruszczynski 39 ). Consistent with previous studies( Reference Mazzarella and Pizzuti 1 , Reference Hallstrom, Vereecken and Ruiz 40 ), breakfast was consumed at least 6 d/week only by 55 % of our sample and more frequently by boys than girls, as already observed in northern Italy and throughout Europe( Reference Vanelli, Iovane and Bernardini 41 , Reference Pearson, Atkin and Biddle 42 ). The consumption of fruit and vegetables is commonly promoted because they are nutrient-dense foods with a potential effect, even if relatively small, in protecting against adiposity in children( Reference Davis, Gance-Cleveland and Hassink 6 ). In agreement with previous surveys( Reference Mazzarella and Pizzuti 1 , Reference Larson, Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan 43 ) the average consumption of fruit and vegetables was very low in the adolescents studied, with only a low percentage of them (2·9 %) consuming at least 5 servings/d. Another marker of a healthy diet is eating non-energy-dense dairy products( 44 ), which are an important source of calcium( Reference Ross 33 ). In our sample only 1·9 % of the adolescents met the guidelines for milk and yoghurt consumption, in line with previous data regarding our region( Reference Mazzarella and Pizzuti 1 ).

In addition to healthy dietary behaviours, lifestyle recommendations for adolescents promote physical activity and the reduction of sedentary behaviours, aiming for better physical fitness and psychological health( Reference Strong, Malina and Blimkie 34 ). In particular, low physical activity and excessive TV watching are both considered in adolescents as significant determinants of excess body fat and cardiometabolic risk factors( Reference Strong, Malina and Blimkie 34 , Reference Crespo, Smit and Troiano 35 ). We evaluated physical activity using a well-established questionnaire (IPAQ)( Reference Hagströmer, Bergman and De Bourdeaudhuij 30 , Reference Strong, Malina and Blimkie 34 ). A threshold of 60 min of MVPA/d, chosen according to evidence-based recommendations( 14 ), was met by 13·6 % of our sample with no gender difference. This value was slightly higher than that reported by the HBSC regional survey (8·1 %)( Reference Mazzarella and Pizzuti 1 ), possibly because of the different methodology. On the other hand, similar results have been obtained, as compared with the HBSC regional survey( Reference Mazzarella and Pizzuti 1 ), with respect to the percentage of adolescents (<50 %) meeting the recommendation for TV watching.

Finally, the consumption of junk snack foods (sweet and savoury products) was also specifically assessed, because of its negative impact on diet quality( Reference Capewell and McPherson 45 ). Quite astonishingly, >65 % of our sample ate at least 1 serving of junk snack foods/d.

As far as we are aware, few papers have focused on the clustering of dietary, physical activity and sedentary behaviours in adolescents. First, we considered the selected health behaviours as dichotomized variables (meeting or not meeting health recommendations): only less than one adolescent out of twenty met three or four recommendations, with the most prevalent cluster represented by having breakfast, performing physical activity and limiting TV watching; while, on the other hand, more than one adolescent out of five did not meet any health recommendation. In a similar study on patterns of nutrition and physical activity behaviours in adolescents, Sanchez et al. ( Reference Sanchez, Norman and Sallis 16 ) reported that only 2 % of Spanish adolescents completely met the guidelines for diet (fat <30 % of total energy and fruit/vegetables >5 servings/d), physical activity (>60 min/d) and sedentary healthy behaviours (TV <120 min/d).

Second, the five health behaviours (having breakfast, eating fruit and vegetables, consumption of milk/yoghurt, performing MVPA, limiting TV watching) were related to each other and with junk snack food consumption. There were significant correlations between the three dietary behaviours. Watching TV was inversely related to having breakfast or eating fruit and vegetables, while junk snack food intake not only negatively correlated with breakfast frequency, but was also positively related to TV watching, possibly because of concurrent eating and/or exposure to food advertising( 46 ). Although a direct comparison with previous data cannot be performed, since the behaviours considered were not strictly the same, a few studies have already confirmed that risk-related behaviours may coexist in young adolescents( Reference Pearson and Biddle 47 – Reference Dumith, Muniz and Tassitano 49 ).

Meeting health recommendations and abdominal adiposity

WC, which is a marker of abdominal fat( Reference Savva, Tornaritis and Sedvva 18 ), has been shown to be related to having breakfast( Reference Alexander, Ventura and Spruijt-Metz 22 ), fruit and vegetable consumption( Reference Bradlee, Singer and Qureshi 23 ), physical activity( Reference Klein-Platat, Oujaa and Wagner 24 ) and sedentary behaviours( Reference Martinez-Gomez, Rey-López and Chillón 25 ). In addition, mounting evidence has demonstrated the benefits of regular physical activity as treatment for abdominal obesity in association with energy restriction( Reference Kim and Lee 50 ).

As far as we are aware, the present study is the first one that has evaluated and clearly demonstrated the association between meeting health recommendations and abdominal adiposity. As the number of health recommendations met decreased, the proportion of adolescents with abdominal adiposity increased (Fig. 1), while no significant trend was observed for the prevalence of OW/OB.

Taking into consideration also the above-mentioned relationships between TV watching and dietary behaviours, such as consumption of junk snack foods( 46 , Reference Francis, Lee and Birch 51 – Reference Harrison and Marske 53 ), it is not surprising that the logistic regression analysis model also identified TV watching as an independent predictor of WHtR in our adolescents. On the contrary, we failed to demonstrate any association between total screen time (TV watching, video game and computer use) and WHtR (r = 0·05), possibly because of the specific behavioural setting of the Neapolitan area (e.g. less time spent using computers).

Overall, the results of the present study are likely to depend on the criteria chosen for defining recommendations. Some healthy behaviours, such as having breakfast and limiting TV watching, more probably entered in the cluster of recommendations met just because they were the most prevalent. Thus, the results of the logistic regression analysis model cannot be interpreted in the sense that the role of fruit and vegetable consumption or MVPA in the prevention of abdominal adiposity should be denied.

We should acknowledge that the study has some limitations such as its cross-sectional design, the relatively narrow age range and the restriction to the urban setting in one southern region of Italy. On the other hand, the strengths of the study are that all data were collected by interview and carefully checked by trained nutritionists rather than self-reported; in addition, all anthropometric data were carefully measured rather than being reported.

Conclusions

The WHO recommends the implementation of strategies in order to face the multiple risks linked to unbalanced diet and sedentary lifestyle. Our study indicates that adolescents not often meet multiple health recommendations on diet and physical activity, confirming that there is a strong need for effective strategies to promote healthy behaviours during adolescence.

In particular, watching TV for ≥2 h/d is the marker more strictly related to abdominal fat in adolescence. We suggest that the calculation of WHtR should be included in health surveillance systems, because not only it is a predictor of cardiovascular risk but also it is sensitive to the effect of unhealthy lifestyle.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: The work was funded by Regione Campania (delibera no. 1687 – 26/11/05). Conflicts of interest: None of the authors had any personal or financial conflict of interest. Ethics: The Ethics Committee of Federico II University approved the study protocol. Authors’ contributions: P.I.I., L.S., A.F. and G.V. provided substantial contribution to the conception and design of the study. P.I.I., N.V., S.M. and C.M. were responsible for the field work of the survey, development of the database and uploading of the data. P.I.I. and G.V. did the analyses and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Acknowledgements: The authors acknowledge Professor Adriana Vaio for her support and collaboration and the schools and pupils for their participation.