Adolescence is a time when the physiological need for nutrients increases and the consumption of a diet of high nutritional quality is particularly importantReference Dwyer, Garrow and James1. A balanced and appropriate diet during childhood and adolescence is likely to reduce the risk of both immediate and long-term health problems2–Reference Gordon5. Poorer quality diet is consistently observed among the more socially disadvantaged groups in societiesReference Roos, Johansson, Kasmel, Klumbiene and Prattala6–9. Social gradients in nutritional intake have been proposed as a possible explanation for the social inequalities observed in a variety of nutrition-related health outcomes among adultsReference James, Nelson, Ralph and Leather10, 11.

Food poverty may be defined as the inability to access a nutritionally adequate diet and the related impact on health, culture and social participationReference Friel and Conlon12, Reference Dowler13. Experiencing food poverty during adolescence has been associated with poor diet and may therefore expose young people to various health risksReference Alaimo, Olson and Frongillo14, Reference Giskes, Turrel, Patterson and Newman15. Previous studies suggested that among children in the USA, household food insecurity, defined as limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods, is associated with poor health-related outcomesReference Casey, Szeto, Robbins, Stuff, Connell and Gossett16, Reference Alaimo, Olson, Frongillo and Briefel17.

The topic of food poverty, food insecurity and food deserts has received some attention in the recent pastReference Cummins and Macintyre18, Reference Dowler19. Within the general population, there is agreement that food poverty is associated with poverty and lower social class status. For example, the UK Food Poverty (Eradication) Bill was passed in 2001 aimed at taking government and local action to eradicate food poverty20. However, despite increased understanding of the parameters of the problem, such policy responses are not widespreadReference Friel and Conlon12.

Moreover, there appears to be a paucity of work investigating the extent of food poverty among adolescents and its associations with social class, food consumption, health and well-being. The present report aims to describe reported food poverty among school-aged children, to investigate the associations between food intake and the experience of food poverty, and to assess the risks of self-reported health and well-being associated with food poverty.

Methods

Sample

This study utilised data from the 2002 Irish Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study, a part of the World Health Organization International collaborative study (WHO-HBSC), carried out among 162 305 schoolchildren in 35 countries. Research teams in all participating countries must follow the same research protocolReference Currie, Samdal, Boyce and Smith21 in order to facilitate entry into the international database and subsequent international analyses. Following this protocolReference Currie, Samdal, Boyce and Smith21, the sampling unit for this study was the classroom. A nationally representative sample of schools (stratified by geographical region) was randomly selected, and individual classrooms within these schools were subsequently randomly selected for inclusion. All mainstream schools, both public and private, were included in the sample frame. Data were collected using a self-completion questionnaire, in April–June and September–October 2002, from 8424 schoolchildren. The response rate in this study was 83% of schoolchildren.

Measurement

The questionnaire was designed by researchers from all 35 participating countries (see Acknowledgements)Reference Currie, Samdal, Boyce and Smith21. Food poverty was defined as those schoolchildren who responded always, often or sometimes to the question ‘Some young people go to school or to bed hungry because there is not enough food at home. How often does this happen to you?’ This question has been validated within the HBSCReference Mullan, Currie, Boyce, Morgan, Kalnins, Holstein, Currie, Samdal, Boyce and Smith22 and in studies in the USAReference Alaimo, Olson and Frongillo14, Reference Alaimo, Olson, Frongillo and Briefel17, and its relevance and applicability has also been demonstrated elsewhere23, Reference Riches24. Children were also asked to report on their father's occupation from which a three-category social class scale was created (social classes 1–2, social classes 3–4 and social classes 5–6). Data on paternal occupation were available for 83% of respondents. Food consumption was measured by a set of questions regarding the frequency of the consumption of a variety of foodstuffs. The various foodstuffs were chosen to capture the relative intake of fibre and calcium, and the consumption foods high in fat, sugar and sodium. The validity and the reliability of this set of questions have been validated among schoolchildren in various countries in Europe and the USAReference Maes, Vereecken, Johnston, Currie, Samdal, Boyce and Smith25–Reference Vereecken, Inchley, Subramanian, Hublet and Maes27. These variables were dichotomised at daily consumption or less of the foodstuffs. The questionnaire also included a question on the frequency of having breakfast, a behaviour associated with nutritional statusReference Resincow28, Reference Siega-Riz, Carson and Popkin29 and which can be reliably assessed with this age groupReference Maes, Vereecken, Johnston, Currie, Samdal, Boyce and Smith25. Breakfast eating was dichotomised at ever missing breakfast or not.

Self-rated health was assessed by the question ‘Would you say your health is?’, with the response options dichotomised at excellent vs. good, fair or poor. Self-rated health is employed as a proxy indicator of health status, with demonstrated applicability for both children and adultsReference Idler and Benyamini30, Reference Torsheim, Currie, Boyce and Samdal31. Children were also asked to report the frequency, in the 6 months prior to the survey, that they experienced a variety of symptoms. These items were used for calculating two indices: those reporting emotional symptoms (feeling low, nervous, bad tempered, afraid, or tired and exhausted) at least once a week during the last 6 months; and those reporting physical symptoms (headache, stomach-ache, backache, dizzy, or neck and shoulder pain) at least once a week in the last 6 months. This symptom checklist represents a non-clinical measure of mental healthReference Haugland, Wold, Stevenson, Aaro and Woynarowska32, Reference Ghandour, Overpeck, Huang, Kogan and Scheidt33. Based on Huebner's (1991)Reference Huebner34 students' life satisfaction scale, children were asked six questions concerning feelings about their life: ‘I like the way things are going for me’, ‘I feel that my life is going well’, ‘I would like to change many things in my life’, ‘I wish I had a different life’, ‘I feel I have a good life’ and ‘I feel good about what is happening to me’. For these six questions, the response options were dichotomised at never and sometimes vs. always and often. Self-reported happiness was measured by the question ‘How do you feel about your life in general?’ and the responses were dichotomised at very happy vs. quite happy, not very happy and not happy at all. Finally, children were asked to rank themselves from 0 to 10 on a life satisfaction ladderReference Cantril35. This scale was used to identify those with low life satisfaction (response < 6). The appropriateness of these well-being items have been previously tested and reported elsewhereReference Hagquist and Andrich36, Reference Torsheim, Ravens-Sieberer, Hetland, Välimaa, Danielson and Overpeck37.

Statistical analyses

Associations between reported food poverty and likelihood of the various outcome measures described above are expressed in odds ratios (ORs) from logistic regression models in SPSS, version 12.0. All analyses were adjusted for age and social class (according to the father's occupation), and were conducted independently for girls and boys. Each table represents a separate logistic regression model. Employing the classroom as the sampling unit, but the individual as the unit of analysis, has the potential to mask clustering effects; nevertheless, previous literature has shown that a cluster effect is less likely in the variables under investigationReference Roberts, Tynjala, Currie, King, Currie, Roberts, Morgan, Smith, Settertobulte and Samdal38.

Results

Compared with 14.6% of schoolchildren in Europe who reported food poverty (ranging from 5.1% in Portugal to 26.8% in Italy), 16.1% of the Irish pupils reported experiencing food poverty (18.7% of boys, 14.2% of girls). This ranged from 15.3% of children from families of lower social classes (SC5–6), to 15.9% from middle social classes (SC3–4) families and to 14.8% of children from higher social classes (SC1–2) (P = 0.50). Small and statistically non-significant differences were also found between the three age groups, with 16.5% of 10- to 11-year-old children, 16.4% of 12- to 14-year-old children and 15.3% of 15- to 17-year-old children reporting food poverty (P = 0.41).

Experiencing food poverty was significantly associated with a poorer diet (less fruit, vegetables and brown bread, and more crisps among girls and fried potatoes and hamburgers among boys) (Table 1). Children reporting food poverty were more likely to miss breakfast on weekdays, with adjusted ORs of 1.29 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.99–1.59) for boys and 1.72 (95% CI 1.50–1.95) for girls.

Table 1 Associations between food poverty and daily consumption or less of various foodstuffs, by gender

OR – odds ratio; CI – confidence interval.

* Adjusted for age and paternal social class.

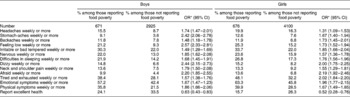

Reported food poverty was also found to be significantly associated with frequent mental and somatic symptoms, poor health (Table 2) and low life satisfaction (Table 3). ORs of ≥ 2 were found among boys experiencing food poverty, indicating an increased likelihood of reporting stomach-ache, feeling low and dizziness. Similarly, among girls experiencing food poverty ORs of >2 were found, indicating an increased likelihood of reporting dizziness, feeling afraid, and feeling tired and exhausted. Both boys and girls experiencing food poverty were significantly less likely to report excellent health. On all measures of life satisfaction, children reporting food poverty were significantly more likely to feel dissatisfied with their life, and were less likely to report that they feel happy. A comparison of the 32 HBSC countries that asked these questions (Fig. 1) confirms this as an international pattern, though showing some variability in the strength of the association, with Ireland ranking about mid-way.

Table 2 Associations between food poverty and measures of health perception, by gender

OR – odds ratio; CI – confidence interval.

* Adjusted for age and paternal social class.

Table 3 Associations between food poverty and measures of reported life satisfaction, by gender

OR – odds ratio; CI – confidence interval.

* Adjusted for age and paternal social class.

Fig. 1 Associations between food poverty and low life satisfaction, by country. *Adjusted for age and paternal social class. Germany, Italy and Russia are represented by regional rather than national samples; Be-VLG – Belgium, Flanders

Discussion

These data indicate a substantial level of food poverty among Irish schoolchildren. They also show that experiencing food poverty is significantly associated with poorer diet, frequent mental and somatic symptoms and low life satisfaction, but not with paternal social class. The current study is based on a large nationally representative sample of schoolchildren and the questionnaire in use was piloted and validated in Ireland as well as in other countries that took part in the international HBSC study in 2001/02Reference Currie, Samdal, Boyce and Smith21, Reference Currie, Roberts, Morgan, Smith, Settertobulte and Samdal39.

It is important to note that this study is cross-sectional in design and thus casual interpretations cannot be made. The response rate in this study is very high; nevertheless, there could be a bias due to non-response, because those absent from school might be particularly different from attendees. In addition, there is a relatively high level of missing data on socio-economic status, which must be considered when interpreting the lack of social class differences in reported food poverty. All data employed here are based on self-reports from children. Although the items employed have been extensively piloted and tested, it is important to bear in mind that there will inevitably be error within these data. Nevertheless, the patterns reported here are both substantial and internally consistent, and thus deserve further consideration.

The association between socio-economic status, diet and health is well established among adultsReference Friel and Conlon12, Reference Dowler13, Reference Giskes, Turrel, Patterson and Newman15 and young childrenReference Alaimo, Olson and Frongillo14, Reference Alaimo, Olson, Frongillo and Briefel17, but not among adolescents. These findings concur with previous literature on the associations between social class and health in adolescence. Whereas strong evidence exists with respect to the importance of socio-economic inequalities in health among adults and young childrenReference Woodroffe, Glickman, Baker and Power40, Reference MacIntyre41, the patterns among adolescents are rarely so clear. Contradictory findings abound in the literature, and vary by measure of socio-economic status, health behaviour or outcome, as well as countryReference West42–Reference Goodman44. Thus adolescence is perceived as a period of relative healthfulness and equality. Although parental occupation is still considered a reliable measure in this age groupReference West42, Reference Abramson, Gofin, Habib, Pridan and Gofin45, Reference Townsend46, other possible measures of socio-economic status among adolescents is an important avenue of investigationReference Currie, Elton, Todd and Platt43, Reference Batista-Foguet, Fortiana, Currie and Villalbi47. However the role of other sources of social inequality also requires consideration.

According to the findings presented here, the association of food poverty with poor diet, negative health and poor life satisfaction among children is over and above measures of social class and is generally stronger among boys than girls. Casey and colleagues previously reported similar gender effectsReference Casey, Szeto, Robbins, Stuff, Connell and Gossett16, which suggest, together with the international comparison presented here, that the associations between food poverty and low life satisfaction are not unique to Ireland and may exhibit considerable cultural variability. Thus, the necessity of considering the different pathways of association between food poverty and health within specific population subgroups is highlighted.

The unequal distribution of the material, social and cultural resources in society results in social inequalities in food, and often in food poverty among some population groupsReference Friel and Conlon12, Reference Shaw, Dorling, Gordon and Davey Smith48. Research in the UK and Ireland has clearly identified material and structural issues of access to and availability of healthy foods as the two main determinants of food povertyReference Dowler and Dobson49. It appears from this study that the risk of being hungry due to lack of food at home can exist across all social classes. This suggests a more complex aetiology of food poverty among children, including matters of material circumstance, psychosocial support, work–life balance of parents, family (dis)organisation, as well as personal and family nutrition knowledge and beliefs, many of which could operate independently of occupational or socio-economic statusReference DeRose, Messer and Millman50.

Access to a safe and varied healthy diet is a fundamental human right. Yet, up until recently, food poverty per se has not received much attention at a policy level in Ireland. However, the recognition of the need for equal access to food for all members of society is embedded within Ireland's new National Nutritional Policy, launched in Summer 2006. One of the key strategic objectives is to help reduce food poverty51. No single approach to tackling food poverty is believed to address all the relevant issues. However, with regard to food poverty among children and adolescents, schools are a powerful, potentially supportive setting, in a position to provide much of the structural and skills development necessary for healthy living. The provision of school meals is a proven beneficial support measure for schoolchildren52, 53. Ongoing dietary programmes in schools are to be commended, but need to be developed and supported nationwide as part of a long-term strategic approach to ensure provision of nutritionally balanced meals for all children.

Acknowledgements

The international 2001/2002 HBSC comprises data from the following countries (principal investigators at that time are given in parentheses): Austria (Wolfgang Dür), Belgium-Flemish (Lea Maes), Belgium-French (Danielle Piette), Canada (William Boyce), Croatia (Marina Kuzman), Czech Republic (Ladislav Csémy), Denmark (Pernille Due), England (Antony Morgan), Estonia (Mai Maser, Kaili Kepler), Finland (Jorma Tynjälä), France (Emmanuelle Godeau), Germany (Klaus Hurrelmann), Greece (Anna Kokkevi), Greenland (Michael Pedersen), Hungary (Anna Aszmann), Ireland (Saoirse Nic Gabhainn), Israel (Yossi Harel), Italy (Franco Cavallo), Latvia (Ieva Ranka), Lithuania (Apolinaras Zaborskis), Macedonia (Lina Kostorova Unkovska), Malta (Marianne Massa), The Netherlands (Wilma Vollebergh), Norway (Oddrun Samdal), Poland (Barbara Woynarowski), Portugal (Margarida Gaspar De Matos), Russia (Alexander Komkov), Scotland (Candace Currie), Slovenia (Eva Stergar), Spain (Carmen Moreno Rodriguez), Sweden (Ulla Marklund), Switzerland (Holger Schmid), Ukraine (Olga Balakireva), USA (Mary Overpeck, Peter Scheidt) and Wales (Chris Roberts).

This study was supported by grant aid from the Health Promotion Unit of the Department of Health and Children, Government of Ireland and by a research project grant from the Health Research Board (HRB). The authors' work was independent of the funders.