Consumption of free sugars by UK adults accounts for 16–17 % of their total energy intake(Reference Bates, Cox and Nicholson1), more than triple the 5 % maximum recommended by the WHO(2). An econometric analysis of repeated cross-sectional data on diabetes and nutritional components of food from 175 countries found that sugar availability is a statistically significant determinant of diabetes prevalence rates worldwide(Reference Basu, Yoffe and Hills3). Briggs et al. estimated that a 20 % tax on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) might result in a 15 % reduction in sugar consumption, potentially preventing approximately 180 000 people in the UK from becoming obese each year(Reference Briggs, Mytton and Kehlbacher4). Evidence from countries such as Mexico(Reference Colchero, Popkin and Rivera5, Reference Colchero, Rivera-Dommarco and Popkin6), Denmark(Reference Smed, Scarborough and Rayner7) and parts of the USA(Reference Silver, Ng and Ryan-Ibarra8) likewise suggests that SSB taxation might be an effective policy in tackling obesity, particularly as part of a multipronged approach(Reference Dobbs, Sawers and Thompson9, 10).

In March 2016, the UK Government announced a Soft Drinks Industry Levy (SDIL), which came into force in April 2018(11, 12). As anticipated, the SDIL led the soft drinks industry to reformulate products to contain less sugar in order to reduce its liability to pay the levy(13, Reference Hashem and Rosborough14). The SDIL represents an important part of the Government’s plan to reduce obesity(15) and dental decay in children(16, Reference Dew17), and also prevent non-communicable diseases associated with excess sugar consumption(Reference Lustig, Schmidt and Brindis18–Reference Malik, Popkin and Bray23). As such, the SDIL has been deemed particularly beneficial to young people and low-income populations who suffer the highest burden of diseases associated with excess sugar consumption(16, Reference Dew17). The SDIL might thus also reduce health inequalities(Reference Mytton24, Reference Powell and Chaloupka25).

Regulatory attempts to reduce consumption of harmful commodities are often met with opposition from producers and marketers of those commodities, and those stakeholders have been shown to use common strategies in resisting the introduction of such upstream regulation. For example, Mialon et al.’s recent systematic review of tactics used by the processed food industry in Australia identified similarities to anti-regulation strategies used by the tobacco and alcohol industries(Reference Mialon, Swinburn and Allender26). Like other so-called ‘unhealthy commodity industries’ (UCI), they used front groups, lobbying and industry-funded research to: (i) emphasise industry responsibility and the effectiveness of self-regulation; (ii) question the effectiveness of statutory regulation; and (iii) frame excessive consumption as the responsibility of individuals, rather than the state(Reference Savell, Gilmore and Fooks27–Reference Ulucanlar, Fooks and Gilmore30). More recently Petticrew et al. suggested that the arguments and language used by the alcohol, food, soda and gambling industries may reflect the existence of a cross-industry ‘playbook’, whose use results in the undermining of effective public health policies(Reference Petticrew, Katikireddi and Knai31). In contrast, there is less evidence of public health advocates using similar tactics to gain support for potentially effective regulation of harmful industry activities. Indeed, such advocates face considerable barriers to effectively influencing policy change, including limited resources, time and appropriate skills(Reference Cullerton, Donnet and Lee32). In the case of minimum unit pricing for alcohol, Katikireddi et al. found that public health advocates worked hard to redefine the policy issue by deliberately presenting a consistent alternative framing of alcohol policy as a broad, multisectoral, public health issue necessitating a whole-population approach(Reference Katikireddi, Bond and Hilton33). The authors considered reframing as vital in enabling policy makers to seriously consider the policy(Reference Katikireddi, Bond and Hilton33). The effectiveness with which stakeholders in a policy debate communicate their arguments is crucial in gaining support for their preferred policy option.

Walton suggests that arguments presented in the media are often used as rhetorically effective techniques to persuade a mass audience(Reference Walton34). The news media is thus a potentially important channel for stakeholders on both sides of any policy debate to promulgate their message. The way that health problems are defined in the news media (i.e. the nature of the problem, its drivers, causal agendas, effects and potential solutions), known as ‘framing’, thus plays a potentially very important role in influencing public and decision makers’ interpretations of health issues(Reference Entman35–Reference McCombs and Shaw37). Public acceptance of a specific policy solution is often a prerequisite for decision makers to implement an evidence-based health policy(Reference Diepeveen, Ling and Suhrcke38, Reference Burstein39) and media framing of problems and solutions can therefore play a key role in determining that acceptability(Reference Innvaer, Vist and Trommald40–Reference Weiss, Wagner, Weiss and Wittrock42), as well as shaping social norms(Reference Joshi and O’Dell43–Reference Hornik and Yanovitzky45).

Systematic reviews of the tactics employed by the alcohol and tobacco industries in attempting to influence marketing regulation have identified a common typology of frames used to argue against such regulation, namely that increased regulation: (i) is unnecessary, (ii) is not backed up by sufficient evidence, (iii) will lead to unintended negative consequences, and (iv) faces legal barriers to implementation; all underpinned by the message that (v) the industry consists of socially responsible companies working toward reducing harmful consumption(Reference Savell, Gilmore and Fooks27–Reference Martino, Miller and Coomber29). While there are subtle differences in different industries’ argumentation, possibly due to their relative positions in the regulatory hierarchy(Reference Martino, Miller and Coomber29), the literature broadly supports the idea that UCI use a cross-industry ‘playbook’ to undermine effective public health policies(Reference Petticrew, Katikireddi and Knai31).

The aims of the present study were therefore to: (i) identify stakeholder arguments used on each side of the SDIL debate in UK newspaper coverage of SSB taxation and compare them with the frames used to resist increased regulation by the alcohol and tobacco industries(Reference Martino, Miller and Coomber29); and (ii) generate insights into how anti-SDIL arguments may be countered to inform future public health advocacy on this and other fiscal policies, both in the UK and worldwide, where there is still considerable resistance to such measures, for example in the USA(Reference Hill and Davis46, Reference Cruickshank47) and Australia(Reference Davey48).

Methods

We used quantitative and qualitative content analysis methods. First, we identified citations of relevant stakeholders in newspapers, their overall presented position as proponents or opponents in the SDIL debate, and the specific arguments in support of or opposing SSB tax attributed to them. Second, we conducted inductive thematic analysis of cited arguments to identify key themes that emerged from the data and compared these with the established typology of industry frames(Reference Martino, Miller and Coomber29).

Newspaper search and article selection

We employed newsprint content analysis based on methods developed by Hilton and colleagues at the University of Glasgow’s Social and Public Health Sciences Unit(Reference Hilton, Hunt and Langan49–Reference Patterson, Hilton and Weishaar52). Eleven UK national newspapers with high circulation figures(53) were selected, along with their Sunday counterparts, to represent three genres: ‘broadsheet’, ‘middle market’ and ‘tabloid’. This typology represents a range of readership profiles diverse in terms of age, social class and political alignment(53, Reference Hilton, Patterson and Teyhan54). The time period of 1 April 2015 to 30 November 2016 was chosen to include coverage triggered by: (i) the publication of reports from the WHO(2), Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition(16) and Public Health England(10); and (ii) the announcement of the UK SDIL (March 2016) and the UK Government’s consultation on the proposed SDIL(55, 56).

The Nexis database(57) was searched for all articles published within the selected publications during the relevant date range that discussed the issue of SSB consumption and taxation. To identify relevant articles, a search string was developed for ‘sugar*’ and one or more of the following terms: ‘beverage*’, ‘soft drink*’, ‘fizz*’, ‘soda’, ‘tax*’ and ‘levy’ occurring anywhere in the text three or more times. The search returned 3127 articles. While the specific policy debate of interest was the SDIL, many stakeholders used the more generic term of ‘SSB tax’ or ‘sugar tax’ when discussing fiscal measures aimed at reducing excess sugar consumption, therefore articles in which stakeholders used any of these terms were included. Hereafter we use the term ‘SSB tax’ unless stakeholders specifically refer to the SDIL.

Articles were excluded if they: (i) did not directly cite stakeholders’ arguments for or against SSB tax or the SDIL; (ii) were short lead-ins to a main story elsewhere in the same edition; (iii) appeared exclusively in an Eire edition; and (iv) appeared in non-news sections of newspapers, including letters, advice, television guide, sport, weather, obituaries or review sections. Letters are routinely excluded from media analysis as they represent the views of individual members of the public rather than stakeholders in the debate. Where a stakeholder provided an opinion piece for a newspaper, this was included in the analysis as a direct citation. After applying the exclusion criteria 2636 articles were removed, leaving 491 for in-depth analysis.

Article coding and stakeholder position analysis

All articles were read in detail by one researcher (R1) to identify and capture the text of direct citations of stakeholder individuals and organisations. Each piece of text was coded for newspaper title, date, individual and/or organisation cited, and whether the argument was in support of, or opposition to, SSB taxation. Where stakeholders used evidence to back up their argument, the type of evidence used was coded. The quantitative coding frame is provided in the online supplementary material (Supplemental File S1: Coding frame used to analyse final sample of newspaper articles). A random sub-sample of 25 % of the articles were double-coded by R2 to ensure coding consistency. Data were imported into the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics version 24 to calculate inter-rater agreement using Cohen’s κ coefficient(Reference Cohen58). Sixty-five per cent of codes returned a κ > 0⋅4, which is typically interpreted as moderate agreement or better(Reference Landis and Koch59). Where less than substantial agreement was identified (κ < 0⋅61), code definitions were discussed within the research team and the coding frame and descriptor document were revised as required.

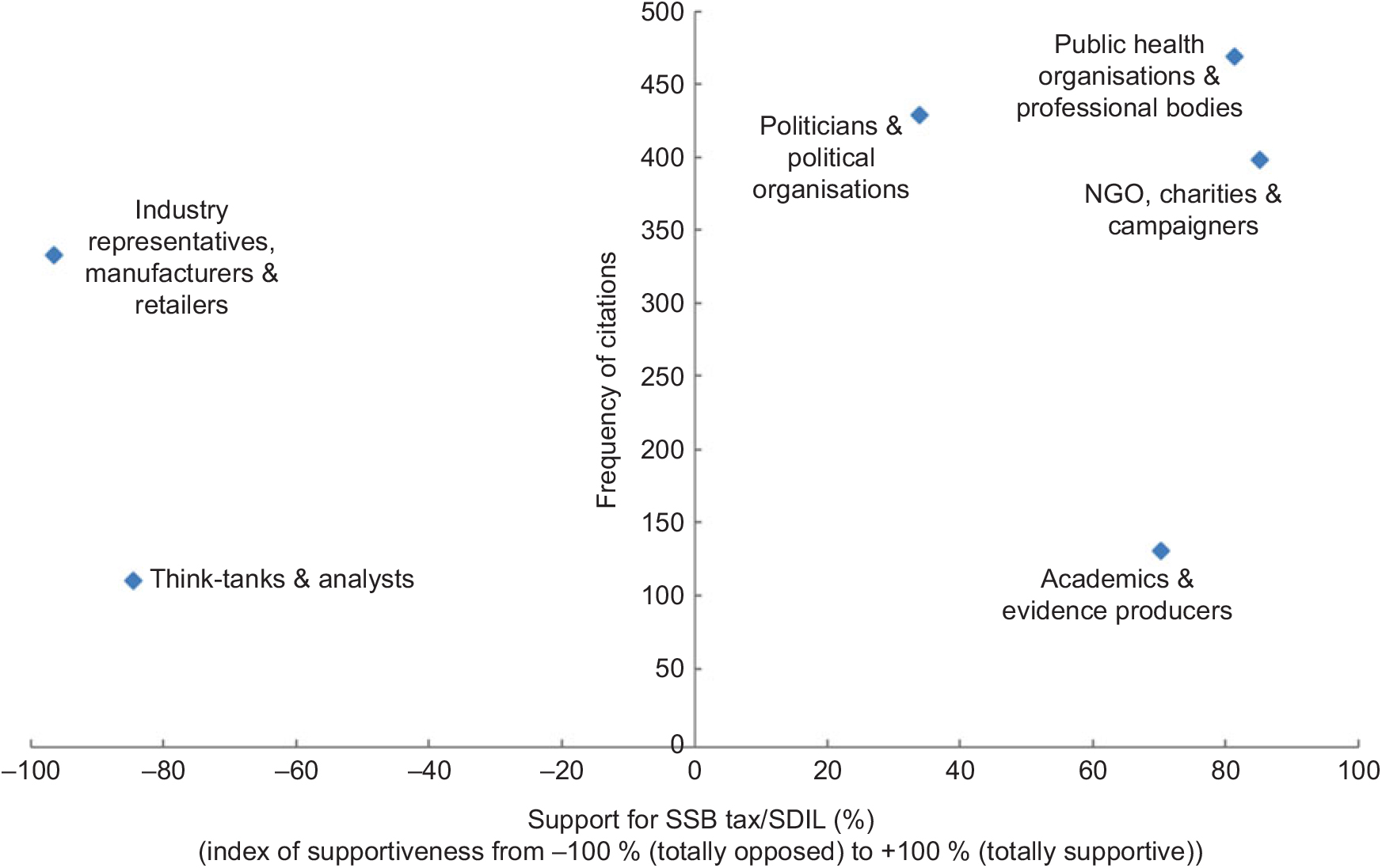

An overview of the slant of opinion by stakeholder was calculated based on an index developed by Patterson et al.(Reference Patterson, Hilton and Weishaar52). The index expresses the proportion of all supportive and oppositional statements associated with a stakeholder as a value on a scale from +100 % (all supportive) to −100 % (all opposed). Cited stakeholders were grouped into six categories according to their organisational affiliations: (i) politicians and political organisations; (ii) public health organisations and professional bodies; (iii) industry representatives, manufacturers and retailers; (iv) non-governmental organisations, health charities and campaigners; (v) academics and evidence producers; and (vi) think-tanks and other analysts. These categories were constructed based on the need to structure the analysis by grouping stakeholders with likely shared values, and were chosen in line with the research team’s prior experience of researching public health policy debates. Individuals and organisations allocated to each group are listed in the online supplementary material (Supplemental File S2: Full list of stakeholder organisations, named individuals, allocation to stakeholder groups). For each stakeholder, the degree of support was then plotted against the total number of times that stakeholder was cited to provide a graphical representation of the most vocal supportive and oppositional groups.

Analysis of arguments in support of and in opposition to sugar-sweetened beverage tax/Soft Drinks Industry Levy

Direct citations were imported into NVivo 11 for inductive thematic analysis. Each piece of text was coded to two separate nodes: stakeholder and theme raised. Individual stakeholder nodes were nested under stakeholder categories, as described above, and thematic nodes were nested under supportive and oppositional categories of argument.

The themes identified were compared with the established typology of industry arguments identified through systematic reviews of research on the alcohol and tobacco industries(Reference Savell, Gilmore and Fooks27–Reference Martino, Miller and Coomber29). In order to compare arguments used by both sides of the SSB tax debate with arguments relating to the regulation of other UCI, we developed a policy-neutral form of this typology (neither opposition nor support for SSB tax): relevance of proposed regulation; evidence; unintended consequences and other benefits; legal; and corporate social responsibility.

Results

Overview

Between 1 April 2015 and 30 November 2016, 491 newspaper articles were identified in which stakeholders were cited as presenting arguments and evidence in the SSB tax debate (Table 1). Most articles were published in UK-wide newspapers (89 %) and 74 % appeared in ‘broadsheet’ newspapers.

Table 1 Number of articles, by region, genre and newspaper title, in the sample of newspaper articles published in eleven UK newspapers between 1 April 2015 and 30 November 2016

A wide range of stakeholders (n 287; 34 % organisations and 66 % individuals) were cited in newspaper articles presenting views on SSB tax (n 1761). A full list of all stakeholder organisations and named individuals is supplied in the online supplementary material (Supplemental File S2). Sixty-five per cent of arguments were in support of some form of SSB tax and 35 % in opposition. Stakeholders infrequently cited evidence in support of their arguments (12 % of the time) and the type of evidence used fell into five categories: (i) academic (citation of a specific academic study); (ii) lay opinion; (iii) expert opinion; (iv) anecdotal; and (v) financial (Table 2). The most frequently used type of evidence was anecdotal (44 %), which was employed by both supporters and opponents of SSB tax. Supporters were more likely to cite a specific academic study or an expert opinion than opponents.

Table 2 Frequency of use of evidence cited in support of and opposition to sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) tax in the sample of newspaper articles published in eleven UK newspapers between 1 April 2015 and 30 November 2016

Overall stance on sugar-sweetened beverage taxation

Plotting the aggregate stance of each stakeholder group against frequency of citations revealed that public health organisations and professional medical associations (the most frequently cited stakeholder group with 25 % of arguments) were most often cited as proponents of SSB tax, as were non-governmental organisations, charities, campaigners and academics (Fig. 1). Groups more frequently cited as opposing the measure included industry representatives and manufacturers (18 % of arguments), think-tanks and economic research organisations. Most stakeholders were cited with consistent arguments, but a minority were cited as making both supportive and oppositional arguments, leaving their degree of support for SSB tax ambiguous and open to interpretation (Supplemental File S2). Inconsistencies arose from: (i) changes in ideological position (politicians and government representatives); (ii) insufficient clarity on the nature of the problem to be solved, excess sugar consumption v. obesity, and policy priorities (public health agencies); and (iii) consistency with academic rigour (academics). The group comprising politicians and political organisations was most diverse in their opinions, in line with the ideological positions held by its constituent stakeholders, with 68 % of arguments in support of taxation and 32 % opposing (Fig. 1). Key individuals in this group (David Cameron, then Prime Minister, and Jeremy Hunt, then Health Secretary) were associated with initial oppositional positions and subsequent supporting positions as the debate developed.

Fig. 1 (colour online) Frequency of citations by stakeholder group and their aggregate stance in the sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) tax/Soft Drinks Industry Levy (SDIL) debate in the sample of newspaper articles published in eleven UK newspapers between 1 April 2015 and 30 November 2016 (NGO, non-governmental organisation)

Thematic analysis and comparison with alcohol and tobacco frames

The themes that arose from the qualitative analysis of stakeholder arguments could be readily classified into the frame/sub-frame structure developed by researchers studying the alcohol and tobacco industries (Table 3). Table 3 presents summaries of typical arguments attributed to stakeholders within articles, organised by stance and frame/sub-frame. Most arguments fell into the evidence (40 %) and regulation frames (31 %), followed by the unintended consequences and other benefits frame (24 %), the corporate social responsibility frame (4 %) and the legal frame (1 %).

Table 3 Summary of frames, sub-frames and key arguments made by opponents and proponents of sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) tax/Soft Drinks Industry Levy (SDIL) in the sample of newspaper articles published in eleven UK newspapers between 1 April 2015 and 30 November 2016. (Frames adapted from Savell et al.(Reference Savell, Gilmore and Fooks27, Reference Savell, Fooks and Gilmore28) and Martino et al. (Reference Martino, Miller and Coomber29))

ASB, artificially sweetened beverage; NCD, non-communicable disease; NHS, National Health Service.

Appropriateness of regulation

The arguments falling into the regulation frame focused on whether or not taxation was an appropriate solution to the problem of obesity. Opponents from the food and drink industry argued that the government should not intervene in the market and that taxation would not prompt behaviour change. For example, the Food and Drink Federation was quoted as stating that: ‘Demonising one nutrient is not a healthy way to proceed. Consumer choice is the best way to go because government intervention simply doesn’t work’ (Independent, 28 August 2015). Some public health agencies opposed the measure because they felt other regulatory mechanisms were of greater priority such as: enforced reformulation and product labelling; control of marketing and promotions; and positive price instruments on healthy products. For example, the President of the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges was quoted as stating that: ‘a sugar tax is probably not top of the list of steps that need to be taken… Higher up would be reformulation of food, and we should curtail marketing of overly sweetened drinks and food like breakfast cereals to children’ (Guardian, 25 October 2015).

Supporters of SSB taxation emphasised the scale of the problem and the urgent need for government action as part of a package of measures, with an emphasis on protecting young people. For example, the National Obesity Forum and Faculty of Public Health made mutually supportive statements: ‘Sugar is indeed the new tobacco. We know it is very harmful to health and we know we can use the same effective strategies that we used in tobacco control’ and ‘A little gentle pressure from sugar taxes and other Government policies will help bring home the message’ (Daily Mirror, 2 November 2016).

Very few supporters highlighted the argument that the SDIL could be seen as a ‘win–win solution’. This position contends that the measure will reduce sugar consumption (by discouraging consumer purchasing and/or encouraging manufacturer reformulation) and raise public revenue that can be reinvested in public health initiatives. The win–win concept was alluded to in the 2016 Chancellor’s budget statement: ‘he wanted to save the nation from an obesity crisis with a tax on fizzy drinks. He said he was convinced that his levy of up to 24p on a litre of fizzy pop would reduce consumption and reap a tax dividend for the exchequer’ (The Observer, 19 March 2016). Supportive stakeholders’ limited invocation of the win–win concept was potentially a missed opportunity to counter opponents’ arguments that sought to position reformulation as a failure of the policy. For example, Investec was associated with that argument: ‘Analysts at Investec said soft drinks makers would reformulate their products to avoid the tax, thereby reducing revenue for the chancellor’ (Sunday Times, 20 March 2016).

Evidence of effectiveness (or lack thereof)

The debate over the evidence bases for supporting or opposing SSB tax centred on the definition of the policy target; that is, reducing sugar consumption v. tackling obesity. Opposing arguments hinged on the likely ineffectiveness of SSB tax in solving the long-term ‘obesity epidemic’, positioning the problem as too complex to solved by a fiscal measure. The Food and Drink Federation was cited as arguing that: ‘Additional burdensome taxes on foods or drinks are rejected by the public. This complex challenge needs a complex solution, one which involves and empowers people, not taxes them’ (Guardian, 4 September 2015). Other opposing arguments included observing that SSB consumption was already in decline, but obesity continues to rise, and arguing that SSB are a sufficiently small source of dietary energy that, even if consumption was reduced, it would have little or no impact on obesity and related non-communicable diseases. For example, the Institute of Economic Affairs was cited as saying: ‘Since soft drink taxes have only a modest effect on the consumption of this relatively minor source of calories, it should not be surprising that there is virtually no evidence sugary drink taxes have reduced obesity or improved health anywhere in the world’ (Times, 13 January 2016).

Conversely, supporting arguments focused on the importance of reducing SSB purchases and thus sugar consumption in the short term, emphasising the impact on specific health concerns such as type 2 diabetes and dental decay in children. Supporters made extensive use of modelling studies and evidence emerging from Mexico to back up their claims. For example, Public Health England was quoted as stating that: ‘The review highlights evidence from Mexico, where a soft drinks tax has led to a six per cent reduction in purchases. The point of the tax is to nudge people away from purchasing these things towards purchasing things that are more consistent with a healthy balanced diet’ (Independent, 20 October 2015).

Three key pieces of evidence were used by stakeholders to support both supportive and oppositional arguments: (i) the McKinsey report entitled Overcoming Obesity: An Initial Economic Analysis (Reference Dobbs, Sawers and Thompson9); (ii) the Public Health England report Sugar Reduction: The Evidence for Action (10); and (iii) a study published in the British Medical Journal evaluating of the impact of the SSB tax in Mexico(Reference Colchero, Popkin and Rivera5) (Table 4).

Table 4 Use of evidence to support stakeholder arguments made in support of or opposition to sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) tax/Soft Drinks Industry Levy (SDIL) in the sample of newspaper articles published in eleven UK newspapers between 1 April 2015 and 30 November 2016

PHE, Public Health England.

Unintended consequences and other benefits (both economic and public health)

Arguments highlighting unintended consequences and other benefits tended to focus specifically on the SDIL rather than SSB taxation more generally. Opponents argued that the SDIL would create negative economic impacts for soft drinks manufacturers, associated industries, the wider economy and consumers, particularly those in lower income groups. Opposing arguments characterised the measure as: regressive; costly to implement; inflationary and likely to cause job losses. For example, the British Soft Drinks Association was quoted as explaining that: ‘Given the economic uncertainty our country now faces, we’re disappointed the Government wishes to proceed with a measure that analysis suggests will cause thousands of job losses’ (Independent, 18 August 2016). Opponents also asserted that the levy would fail to raise the anticipated public revenue as manufacturers would reformulate their products to avoid paying it, positioning this as a negative outcome rather than the positive one suggested in the win–win solution.

Opposing arguments also emphasised the potential negative health consequences of consumers replacing SSB with other sources of sugar or artificially sweetened beverages, suggesting that sugar is addictive and artificially sweetened beverages are no better for health than SSB. The Institute for Fiscal Studies was quoted as reasoning that: ‘If people have a strong taste for sugar, although they may respond to the increase in prices by switching away from sugary soft drinks, it’s entirely possible and quite likely they might switch towards other high sugar products’ (Daily Mail, 18 March 2016).

In contrast, supporters of the tax argued that there would be no adverse economic impact for industry or consumers, as the design of the SDIL allowed industry two years to reformulate its products with less sugar and that consumers could choose from many alternatives to SSB and thus avoid the levy entirely. Additional benefits of the SDIL were highlighted in terms of: (i) the potential for reinvestment of revenue raised into health improvement programmes and subsidies for ‘healthy’ foods; (ii) the positive long-term impact of reduced non-communicable diseases on increased productivity and a reduced burden on the National Health Service; and (iii) sending a strong message to industry and consumers about the health impacts of excess sugar consumption. For example, the WHO was quoted as suggesting that: ‘Fiscal policies may encourage this group of consumers to make healthier choices (provided healthier alternatives are made available) as well as providing an indirect educational and public health signal to the whole population’ (The Herald, 26 January 2016).

Legality issues

Insurprisingly, only opponents of SSB tax were cited as making arguments highlighting the legality and potentially anti-competitive nature of the measure. For example, the British Soft Drinks Association stated: ‘It’s fair to say we are more than just considering legal action. This has been rushed through without warning’ (Sunday Times, 20 March 2016). However, this line of argument was transient, surfacing only briefly at the time of the SDIL announcement in early March 2016, and disappearing by the end of that month. The Telegraph (30 March 2016) quoted AG Barr as saying: ‘[we are] fully committed to working with the Treasury on a full consultation that will have an outcome that benefits consumers, shareholders and other stakeholders’, and added that ‘Mr White said that a legal challenge to the sugar tax was not being considered’. This was in contrast to the response of the alcohol industry to the announcement of minimum unit pricing for alcohol in Scotland, where a legal challenge significantly delayed implementation.

Role of corporate social responsibility

The final frame represents a line of argument again primarily espoused by opponents of SSB tax: that the soft drinks industry has a positive role to play in promoting public health and that it is voluntarily reformulating its products to be healthier in response to consumer demand, without the need for taxation or other regulation. For example, one soft drinks manufacturer was quoted as stating that: ‘Our job is to understand and have relationships with our customers, which we have had for over 100 years, making sure we offer them choices. In stark contrast to other food and drink categories, we have been reducing sugar content and have a strong [commitment] to do so’ (Guardian, 29 March 2016). Conversely, supporters of the measure questioned whether or not working in partnership with industry and relying on voluntary action had worked, pointing out the failure of the Public Health Responsibility Deal(60). For example, a Liberal Democrat MP was quoted as stating that: ‘The whole approach has been based on voluntary action. The question is whether that has succeeded. I don’t think anything fundamentally has changed. We need to rethink our approach and ask if it has led to too cosy a relationship with the food industry’ (Daily Mail, 24 October 2015).

Discussion

Our media content analysis revealed 1761 arguments made by 287 stakeholders in the debate about SSB tax across 491 UK national newspaper articles, which is comparable with similar public debates on other policy measures such as e-cigarette regulation(Reference Patterson, Hilton and Weishaar52) and minimum unit pricing for alcohol(Reference Katikireddi and Hilton61, Reference Patterson, Katikireddi and Wood62). Supportive statements outnumbered opposing ones by almost 2:1. The most frequently cited supporters of SSB tax were public health organisations and professional medical associations, while the most frequently cited opponents were soft drinks industry representatives. Both supportive and opposing arguments aligned with a typology framework developed for studying the alcohol and tobacco industries(Reference Savell, Gilmore and Fooks27–Reference Martino, Miller and Coomber29).

Stakeholders on each side of the debate sought to use evidence to support their arguments; however, opponents were less likely to refer to specific academic studies and more likely to use anecdotal evidence. Interestingly, the same reports were sometimes invoked by both proponents and opponents to support their differing arguments but using subtly different framings. The effective use of evidence is a potentially important factor in influencing public support for proposed policy interventions(Reference Diepeveen, Ling and Suhrcke38, Reference Oxman, Lewin and Lavis63). However, a systematic review by Orton et al. found that policy makers’ sceptical view of research evidence can create a key barrier to its use(Reference Orton, Lloyd-Williams and Taylor-Robinson64). Our findings on how evidence was used by stakeholders in the SDIL debate reinforce the importance of trustworthiness and reliability in the way research is represented, and then used or dismissed.

The use of taxation as an intervention to influence consumer behaviour and reduce consumption of unhealthy commodities is a well-established public health policy that has been used effectively in relation to both tobacco and alcohol(Reference Blecher65, Reference Burton, Henn and Lavoie66). However, a recent systematic review by Wright et al. highlighted the importance for policy actors to be clear about the primary objective of any health tax, be it for fiscal or health purposes, and to frame the tax accordingly(Reference Wright, Smith and Hellowell67). Failure to do so leaves a proposed tax vulnerable to hostile lobbying(Reference Wright, Smith and Hellowell67). Our study identified inconsistencies in argumentation from three possible sources: (i) changes in ideological position (politicians and government representatives); (ii) insufficient clarity on the nature of the problem to be solved and policy priorities (public health agencies); and (iii) consistency with academic rigour (academics). Whether a policy is anticipated to produce single or multiple outcomes, proponents need to identify the outcome or outcomes clearly and consistently. More clearly positioning the SDIL as a win–win solution, both lowering sugar consumption and raising revenues that can be reinvested in health service funding, could have been a useful, pragmatic approach to pre-empt opposing arguments. The limited invocation of that perspective may perhaps represent a missed opportunity for proponents of the policy.

A key strategy employed by other UCI to oppose upstream regulation is the complexity argument, which Petticrew et al. characterise as ‘nothing can be done until everything is done’(Reference Petticrew, Katikireddi and Knai31). Opponents of SSB tax employed this tactic by emphasising the complexity of the obesity problem and therefore the inappropriateness of discrete legislative measures. Proponents apparently countered this by strategic simplification; that is, by focusing on the specific health-harming effects of excess sugar consumption, particularly from SSB for young people. They further emphasised that the SDIL was not intended to be a ‘silver bullet’ to tackle obesity, but a small and important first step focusing on a commodity with negligible nutritional value. Similar, apparently deliberate, attempts to reframe policy debates were previously used by public health advocates in the case of minimum unit pricing for alcohol(Reference Katikireddi, Bond and Hilton33) and by supporters of legislation to prohibit smoking in private vehicles carrying children(Reference Patterson, Semple and Wood68).

Advocates clearly need to continue to use effective arguments and embrace the persuasive power of framing. However, public health advocates and academics should also be aware of the potential for their over-critical analyses of nuanced aspects of policy measures to result in ‘mixed messages’ when filtered through media gatekeepers. Nuance is a strength of academia, and many academics are understandably wary of media commentators championing public health policies. However, complex messages have the potential to create public confusion and actually undermine the intended public health objectives. Academics readily acknowledge uncertainty, but uncertainty rarely has a place in clear public communication(Reference Capewell69). Researchers lacking media skills can thus find themselves uncomfortably positioned in complicated moral and affective landscapes, toiling to represent the nuance of their research(Reference Lucherini70). The challenge is to communicate the core truth simply, but without dumbing down the message into simplistic dichotomy. The mass media lens may depict rigorous academic circumspection as fragility of position, while industry representatives opposing regulation are unlikely to concede any uncertainty(Reference Capewell69).

We suggest that, in a bid to downplay the contribution of SSB to non-communicable diseases, the soft drinks industry employed tactics previously used by other UCI by ‘directly lobbying’ the public and policy makers, shifting blame for obesity to complexity and optimistically trying to characterise the soft drinks industry as promoting healthy lifestyles(Reference Kearns, Schmidt and Glantz71). Our study also supports the findings of the systematic review by Mialon et al. that information and messaging is one of the most prominent corporate political activities employed by food industry actors(Reference Mialon, Swinburn and Allender26).

Our study has relevance beyond debates about SSB tax. These data add to a growing body of research demonstrating the similarities in frames promoted by different harmful commodity industries across public health policy debates(Reference Savell, Gilmore and Fooks27, Reference Savell, Fooks and Gilmore28, Reference Ulucanlar, Fooks and Gilmore30, Reference Petticrew, Katikireddi and Knai31). Our research may therefore help to inform future media strategies by advocates of upstream legislative public health measures targeting a range of harmful products, including sugar, tobacco(72) and alcohol(73). In particular, it may be helpful for public health proponents to support arguments with high-quality evidence, to communicate the subtleties of health policy development without undermining key objectives, and to be aware of the apparent shared UCI ‘playbook’(Reference Petticrew, Katikireddi and Knai31).

Our research strengths include a rigorous approach which offers a robust examination of the newspaper debate around SSB tax. By coding and analysing direct quotations of stakeholders, we sought to minimise the impact of editorial gatekeepers and achieve greater fidelity than the more commonplace approach of analysing entire news articles. Our study is subject to the limitations which are intrinsic to media content analysis. First, these data do not necessarily represent stakeholders’ intended positions, rather a collaboration between stakeholders and media gatekeepers, whereby those positions have been mediated, interpreted, filtered and contextualised by journalists and editors. However, our exclusive use of quotes from individuals and directly attributable citations partly mitigates against this. Second, newspapers represent only one forum in which policy debates play out. Our analysis therefore omits the parliamentary arena, the judicial arena, social media and any non-public discussions that take place ‘behind closed doors’. However, understanding public debate in the media arena still offers a useful ‘door opener to the backstage of politics’, as Wodak and Meyer argue(Reference Wodak and Meyer74). A more comprehensive understanding of stakeholders’ strategies might be triangulated from studying other forms of media, policy documents or consultation responses, and conducting interviews with stakeholders. Third, this form of representational content analysis cannot (and does not seek to) assess the effectiveness of stakeholder media communication strategies, only their implied intention. Further research on public perceptions of media messaging and stakeholder intention might usefully help to complete the picture.

Conclusion

Public health advocates were particularly prominent in the debate surrounding the SDIL in UK newspapers. Mass media engagement can be used to influence how the public and policy makers understand health problems and their solutions and thus the acceptability of specific policies(Reference Entman35, Reference Otten75). Research into how public health policy debates unfold in the media may help to inform improved media advocacy strategies(Reference Weishaar, Dorfman and Freudenberg76). Opponents’ arguments resembled those used by the alcohol and tobacco industries in prior policy debates. Advocates in future policy debates could benefit from seeking a similar level of prominence and avoid inconsistencies by being clearer about the policy objective and mechanisms.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank colleagues at the MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit at the University of Glasgow, particularly Dr Amy Nimegeer for her contribution to the initiation of the study, and Dr Alison Parkes and Ms Mhairi Campbell for their review and comments. Financial support: This work was supported by the UK Medical Research Council as part of the Informing Healthy Public Policy programme (MC_UU_12017/15) and by the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health Directorates (SPHSU15) at the MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow. S.V.K. is funded by an NHS Research Scotland Senior Clinical Fellowship (SCAF/15/02). The UK Medical Research Council, the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health Directorates and NHS Research Scotland had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: S.V.K. is a member of the steering group of Obesity Action Scotland, to whom he provides unpaid advice on the evidence base for public health actions to tackle obesity. S.C. is a Trustee for Heart of Mersey, UK Faculty of Public Health and UK Health Forum and provides unpaid advice to Action on Sugar. All other authors have declared no potential conflicts of interest. Authorship: S.H.: conceptualisation, study design, funding acquisition, supervision, data interpretation, manuscript writing, review and editing. C.H.B.: study design, project administration, investigation, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, manuscript writing, review and editing. C.P.: study design, investigation, data analysis, data interpretation, manuscript writing, review and editing. S.V.K.: study design, data interpretation, manuscript review and editing. F.L.-W.: study design, data interpretation, manuscript review and editing. L.H.: study design, data analysis, data interpretation, manuscript review and editing. A.E.-G.: study design, manuscript review. S.C.: conceptualisation, study design, supervision, data interpretation, manuscript review and editing. Ethics of human subject participation: No approval was required.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019000739

Author ORCID

Shona Hilton, 0000-0003-0633-8152.