Malnutrition is a public health and development problem in Burkina Faso and West Africa(Reference Remans, Pronyk and Fanzo1–Reference Black, Allen and Bhutta3). Despite increased momentum in recent years, progress towards the World Health Assembly targets remains slow(4). Continuing business as usual will jeopardise the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals(5). While there exist strong policies, their implementation is weak(Reference Florentino, Adorna and Solon6) and fragmented, limiting their effects from being maximised(Reference Alpha and Fouilleux7,Reference Garrett and Natalicchio8) .

In Burkina Faso, the prevalence of stunting among children under five decreased from 35·1 % in 2009 to 25·0 % in 2018, but the absolute number of stunted children during the same period did not decrease(4). The global acute malnutrition declined slightly from 11·3 to 8·4 %.

It has been shown that the fight against stunting and other forms of malnutrition requires a multisectoral approach that offers a package of both nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions with high coverage of beneficiaries while ensuring geographical convergence(Reference Garrett and Natalicchio8–Reference Ruel and Alderman11). In fact, several studies have provided evidence of the effectiveness of multisectoral programmes in improving indicators of infant and young child feeding (IYCF) and reducing stunting(Reference Remans, Pronyk and Fanzo1,Reference Reinhardt and Fanzo9,Reference Cunningham, Singh and Pandey Rana12) . For example, in Brazil, stunting prevalence was reduced by half (50 %) from 13·5 to 6·8 % between 1996 and 2006/2007. According to Monteiro, two-thirds of this reduction in the stunting rate could be attributed to a multisectoral approach that had been implemented(Reference Monteiro, Benicio and Conde13).

An observational study on stunting in children exposed to multisectoral interventions in nine sub-Saharan African countries found a significant reduction in the prevalence of stunting in five of the countries(Reference Remans, Pronyk and Fanzo1).

The Government of Burkina Faso has been engaged in a national nutrition planning process since 2014 with political reforms for a comprehensive approach multisectoral programming. Key actions included the strengthening of multisectoral coordination, the revision of national nutrition policy, the development of a Multisectoral Nutrition Strategic Plan and the integration of nutrition into sectoral policies(Reference Maimouna, Ouedraogo and Ouaro14–Reference Doudou, Ouedraogo and Ouaro16). In addition to this political leadership at the central level, locally elected officials have also committed to contributing to scaling-up nutrition-sensitive interventions through the integration of nutrition objectives with indicators in the Communal Development Plans and to fostering multi-stake holder dialogue and coordination at the subnational level(Reference Ouedraogo, Doudou and Drabo17).

At programmatic levels, several models of multisectoral action plans have been designed, with integrated intervention packages at the community level(Reference Ouedraogo, Doudou and Drabo17). IYCF, which has been identified by the Lancet series as one of the top ten most effective interventions in preventing stunting with the window of opportunity of the first thousand days of life, is a flagship intervention of the Burkina Faso strategic plan(Reference Ouedraogo, Doudou and Drabo17,Reference Sodjinou, Cisse and Tapsoba18) . A scaling-up plan has been developed to gradually scale up the programme in all regions of Burkina Faso with the involvement of all relevant sectors.

As implementation continues and challenges occur, the main question that has arisen from stakeholders is the understanding of the determinants of a successful nutrition multisectoral programme at the community level(Reference Ouedraogo, Doudou and Drabo17,Reference Sodjinou, Cisse and Tapsoba18) . The quality of the implementation process is a critical aspect of programme effectiveness and, in the case of Burkina Faso, maximising the effects and impacts of the multisectoral implementation of IYCF interventions is another critical aspect. Most studies focus on the causes of malnutrition and impact assessments of interventions(Reference Reinhardt and Fanzo9,Reference Meessen, Kouanda and Musango19) . Given the scarcity of evidence on the successful service delivery of multisectoral nutrition programmes and lessons learned, such contributions that examine what makes the implementation of these programme successful become critical for nutrition programmes(Reference Fajardo20,Reference Tumilowicz, McClafferty and Neufeld21) .

This study was undertaken in three health districts of northern Burkina Faso, with the aim of identifying and analysing the challenges and enabling factors that affect the implementation of a multisectoral community nutrition programme and that are associated with its performance.

Methods

Programme description

The programme of focus for this study covered three provinces (Yako, Gourcy and Titao) in the northern region of Burkina Faso, one of the two regions that benefited between 2013 and 2014 from the pilot phase of the IYCF scaling-up plan supported by UNICEF under the Africa’s Nutrition Security Partnership and where plausible improvements in IYCF indicators were reported(Reference Sodjinou, Cisse and Tapsoba18). Lessons learned from this pilot phase informed the design of a follow-up programme in 2017–2018, which involved five key programmatic sectors, namely agriculture, environment, livestock, primary education and health.

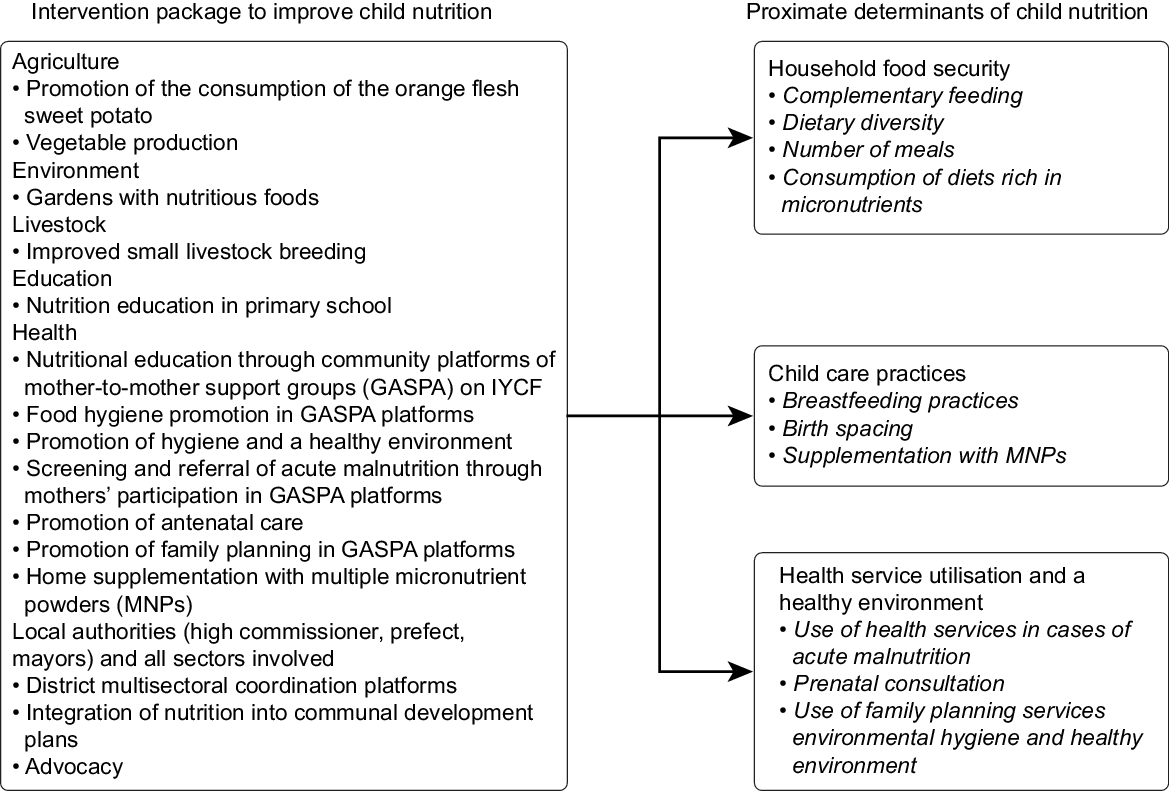

The current study focuses on the 2017–2018 programme, which aimed to increase the coverage of IYCF best practice interventions and to reduce the prevalence of stunting. The main beneficiaries of the programme were 29 494 pregnant women and 42 679 mothers of children aged 0–23 months. The integrated multisectoral package consisted of high-impact nutrition interventions (Fig. 1) in the five sectors. The interventions in the education sector only covered the province of Passore with nutrition education in primary school. In addition, actors from the five sectors of the government, eight community-based organisations with 1015 community health workers (CHW) and 235 volunteer resource persons were involved in the implementation. A grant in the form of a cash transfer of 42 USD was provided to support small livestock rearing.

Fig. 1 Overview of project interventions to improve nutrition and the proximate determinants of child nutrition

Study type and site

This was a qualitative study conducted in three health districts each from the provinces of Passore, Zandoma and Lorum in the northern region of Burkina Faso.

Identification of influencing factors and lessons learned through qualitative approaches

We used qualitative methods to identify the enabling factors, challenges and lessons learned from the implementation of a multisectoral, community-level programme. Data were collected through in-depth individual interviews with key stakeholders involved in the programme implementation. Focus groups were also conducted with mothers of children under the age of two who benefited from the programme and direct observations. Finally, a consultative workshop was held to consolidate and triangulate the findings.

A semi-structured interview guide was administered in March 2019 to respondents selected primarily based on their high-level involvement in the implementation process. A purposive sampling method taking into account diversity and categories of actors involved in the implementation of the multisectoral programme was employed:

Provincial sector heads and technical agents from five contributing sectors, i.e. health, agriculture, environment, livestock and education.

Community actors, including staff from the eight community-based organisations, CHW and volunteer resource persons at the village level.

Respondents from public institutions, community-based organisations and villages were selected in each of the three provinces where the programme was implemented.

Individual interviews focused on the following dimensions: (i) success factors, (ii) barriers or challenges in implementing the multisectoral approach, (iii) the sector and community participation levels, (iv) multisectoral coordination, (v) convergence and integration of interventions, (vi) capacity of actors and the availability of resources, (vii) monitoring and evaluation and social accountability, (viii) context, (ix) sustainability of the programme, (x) lessons learned in the implementation of multisectorality and (xi) prospects for the successful implementation of multisectoral nutrition programmes.

A team of four investigators consisting of two social anthropologists and two nutritionists who had experience in qualitative research conducted the individual interviews. Interviewers were trained for 5 d on data collection and the interview guide was pretested at the end of the training, and the tools were adjusted before the data collection phase in the field.

The investigators continued to conduct individual interviews and triangulate the data until saturation was reached. In addition to individual interviews, a focus group discussion was conducted in each of the target health districts. Focus groups were carried out with beneficiaries and mothers of children under 2 years of age, and discussions were focused on the following points: (i) the use of products from raising small livestock and the consumption of orange-fleshed sweet potatoes and small-scale gardening products; (ii) the barriers faced by mothers; (iii) sociocultural barriers to the adoption of best nutrition practices and (iv) perceptions of the programme interventions.

Direct observations consisted of visits to improved food production sites to observe product types and facilities. The in-depth interviews and focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The discussions were coded, analysed using QDA Miner software and synthetised by themes and subthemes. Deductive and inductive approaches were used for this interview content analysis. This analysis was performed by an assistant researcher and verified by the lead researcher.

The results from individual interviews and focus groups were presented to all stakeholders during a triangulation workshop with thirty-two participants from the three health districts, the five public sectors and beneficiaries. This workshop was facilitated by two independent researchers. The aim was to triangulate the findings and explore additional emerging issues from the interviews.

An adaptation of the theoretical framework on multisectorality in nutrition(Reference Haddad, Acosta and Fanzo22,Reference Jerling, Pelletier and Franzo23) and the key factors for successful programme implementation derived from implementation science(Reference Durlak and DuPre24,Reference Pinto and Slevin25) were used for the design of the study and to develop the interview guides. The framework also guided the data analysis. This adapted conceptual framework includes seven key factors (drivers and challenges) influencing the implementation of multisectorality at the community level (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Theoretical framework for analysing the factors influencing the implementation process of multisectoral nutrition programmes at the community level

Results

Participants’ characteristics

A total of forty-seven key informants involved in the implementation of the multisectoral nutrition programme at the community level participated in individual interviews (Table 1). These actors included programme implementers in the five public sectors including health, agriculture, environment, livestock and education; community members, namely, the staff of associations, CHW and community leaders. The CHW had a primary school education level. Three focus group discussions were conducted with twenty-four mothers (eight per group) of children under 2 years of age.

Table 1 Distribution of respondents by socio professional profile

Success factors and challenges of implementing the integrated multisectoral nutrition

Most of the factors influencing the implementation of multisectorality were common among the three health districts. The main themes highlighted by the respondents are grouped in Table 2.

Table 2 Summary of the key success factors and challenges of implementing a multisectoral nutrition programme at the community level in Burkina Faso’s Northern Region

OFSP, orange-fleshed sweet potatoes;s

Factors related to community participation

Community involvement and engagement were identified as key factors in the success of the programme’s implementation. During the formulation phase of the programme, the population was consulted through community-based village-level diagnostics to understand the real needs and guide the necessary actions.

Frontline community actors who worked as nutrition education actors in implementing the programme were recruited locally within the community; the selection process was participatory, and these actors were designated by the community itself. Public adherence to the programme, social acceptance and the strong involvement of beneficiaries were among the facilitating factors. Some mothers who received cash transfer for small livestock rearing received support from their husbands, which made it possible for them to build chicken coops. Implementing stakeholders and beneficiaries reported that a limiting factor was related to the difficulties in mobilising women for nutrition education sessions on IYCF during the rainy season due to their occupation with work in the fields.

Factors related to the capacity of actors and the availability of resources

The main factors that positively influenced the programme implementation were the motivation of community actors who felt valued by the activities; the existence of a large network of CHW, with at least two per village and the experience of the community-based associations in the field of IYCF. These structures have been pioneers in the implementation of the community component of IYCF activities at the national level since 2013, when the pilot phase of the scaling-up plan was implemented.

Capacity building of community actors through training in nutrition education on IYCF and in technical aspects related to nutrition-sensitive interventions, including the promotion of small-scale livestock farming, promotion of orange-fleshed sweet potato and home gardening to produce nutritious food for consumption and sale and technical support to the beneficiaries, were key factors for success.

However, respondents from some sectors noted inadequacies related to mothers’ low level of mastery of nutrition-sensitive intervention techniques (small livestock rearing, nutrition-sensitive agriculture, etc.), the low level of education of CHW and the insufficient number of CHW compared with the number of beneficiaries to be covered mainly in the ‘big villages’.

The technical support provided by the sectors through capacity building for community actors and supervision was identified as supporting factors. In addition, the existence of local nutrition champions, called ‘Volunteer Resource Persons’, who were often village and religious leaders, to support community advocacy and awareness through dialogues was one identified as one of the key success factors. As one of the leaders of implementation associations recalls about a champion in nutrition ‘In a village this year, the head even brought the species of orange fleshed sweet potato (OFSP) and cultivated it cleanly in his village. He set an example to the community, encouraged local production of the OFSP and gave a strong message to the population by raising awareness that the OFSP is very rich in vitamin A and helps to combat child malnutrition. The customary chiefs help us because their words carry a lot of weight; when it’s the chief who says it’s easy, everyone follows’.

At the sector level, the lack of human resources, the high staff turnover, conflicts of agenda and insufficient financial incentives to participate in community activities were identified as barriers. One of the CHWs reported, ‘There is a problem with many of the health workers accompanying us in our activities because they often don’t have the time’.

The lack of financial resources to cover the needs of the entire target population with the entire integrated package was one of the major constraints observed by the implementers. In addition, some beneficiaries believed that the amount of grant in the form of cash transfer was insufficient to set up small livestock rearing. Co-financing by partners such as UNICEF and the FAO was a facilitating factor in mobilising resources for implementation.

Factors related to sector participation, collaboration and multisectoral coordination

The involvement and participation of the various sectors in technical support and the strengthening of the skills of community workers for multisectoral implementation were noted as key determinants of success.

Indeed, the majority (90 %) of the interviewees felt that the level of involvement and participation of sectors were overall good or satisfactory. The level of participation varied by sector, with a high level of participation in the health sector and little involvement in the livestock, agriculture, environment and education sectors. A community actor explained, ‘There is good involvement of the health services, as they accompany us in our activities of nutrition education and culinary demonstrations. Health workers are very involved because when we talk about nutrition, people see health more than other sectors’.

Sector participation was facilitated by the implementers’ areas of expertise in relation to the themes covered, advocacy, good collaboration, information sharing, good communication, periodic meetings, joint operational planning of field activities and financial motivation.

On the other hand, factors limiting sector participation included insufficient communication, such as the late arrival of some invitation letters; low involvement of sectors in operational planning; lack of conventions; insufficient definition and clarification of the roles expected of the different sectors; lack of financial resources to motivate sector actors; high workload in some sectors and agenda conflicts. A community actor stated, ‘It is the scheduling conflicts that delay the programming of certain activities with the districts’.

Implementing stakeholders also noted that good collaboration and coordination were key determinants of the quality of multisectoral implementation.

Most respondents felt that the collaboration between community-based organisations and the public sectors was good. However, the collaboration of community-based organisations with the non-health sectors was limited in the absence of a contract.

Furthermore, one of the main barriers mentioned was the verticality, that is, the habit of the sector actors to work in ‘silos’, resulting in insufficient cross-sector collaboration for the various technical services (health, livestock, agriculture, environment and education). As one respondent noted, ‘Everyone’s sector works on their own’.

In addition, the programme tested a decentralised multisectoral nutrition coordination platform at the province level in Passoré. This multisectoral platform brought together more than six sectors, municipalities and civil society and was under the leadership of the high commissioner, who provided horizontal governance, while the district physician acted as the technical secretariat. In Passore, most respondents were unanimous that the decentralised multisectoral nutrition coordination platform in the province contributed to raising awareness of stakeholders in the sectors involved of the importance of the fight against malnutrition, enhanced their commitments and understanding of the need for a multisectoral approach and their roles. One of the respondents said, ‘This multisectoral coordination platform allows different sectors to sit down together and take a look at nutrition promotion. Very often, this framework of exchanges does not exist, and this creates overlaps on the ground related to the lack of coordination’.

Challenges existed of the provincial platform, including the sessions did not take place regularly. Some sector respondents also noted the multiplicity of coordination frameworks with the over-mobilisation of stakeholders. The lack of a multisectoral nutrition coordination platform in two of the three districts/provinces was identified as a key limiting factor.

Factors related to geographical convergence and the integration of interventions

Respondents reported that geographic convergence to provide an integrated package of multisectoral interventions to beneficiaries was the key driver of successful multisectoral implementation. However, there was low geographic and target group coverage mainly for the nutrition-sensitive interventions, as well as disparities between the three provinces. Most mothers of children under 2 years benefited from nutritional counseling on IYCF, but nutrition-sensitive interventions involving the promotion of the consumption of orange-fleshed sweet potatoes, home gardens with nutritious foods and small livestock rearing covered less than half of the beneficiaries.

Most respondents stated that the integration of interventions to provide a package of services to mothers of children was an important factor. To this end, the model of community-based mother-to-mother support group platforms for the promotion of IYCF best practices, commonly referred to as ‘GASPA’, was cited by most respondents as an effective approach. These respondents indicated that the community platforms acted as a gateway to providing an integrated and multisectoral service package.

The difference in beneficiary targeting strategies between sectors was a major constraint to the integration of nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions. Health sector-level targeting was geared towards children under 5 years of age and pregnant and lactating women, while in agriculture and livestock sectors, targeting was directed towards poor and most vulnerable people. In addition, there was also a difference in the geographical targeting criteria for the intervention zones by sector.

Factors related to monitoring, evaluation and social accountability

The programme contributed to nutritional monitoring through mid-upper arm circumference screening of children and the participation of their mothers in the GASPA platforms. In addition, the programme enabled the development of reporting tools for IYCF activities at community level. The gaps identified were related to the varied and burdensome data collection tools and the inadequacy of community data entry into the District Health Information System. Additional constraints included the absence of a multisectoral monitoring system with a database recording all the programme’s multisectoral interventions and the absence of a social accountability mechanism for beneficiaries.

Factors related to the context

Implementing actors stressed that the persistence of certain traditional beliefs about food taboos was a major obstacle to the adoption of good IYCF practices. For example, a belief holds that ‘if a child consumes eggs, he will become a thief’; therefore, children should not consume eggs. Although most mothers in the focus group said that they used food obtained from improved production practices, some mothers admitted that they had not given their children enough of these foods. A community actor said, ‘The OFSPs are given, but the eggs, some moms used to sell them’.

The insecurity of the northern region due to terrorist attacks was a new constraint reported by implementing actors. One of the respondents stated, ‘With insecurity, gathering in groups is prohibited, and there are increasing displacements and humanitarian access problems in villages where there are terrorist attacks with armed groups’. This insecurity resulted in difficulties bringing mothers together in certain communities to carry out nutrition education activities on IYCF.

Factors related to the sustainability of the programme

The majority of respondents noted that the programme was sustainable. For them, the nutrition education on IYCF itself made it possible to sustain the achievements of the programme; as one respondent noted, ‘Educating mothers prevents a recurrence of the problem of malnutrition’. Mothers’ participation in malnutrition screening was also an element of sustainability.

Other cited sustainability factors were related to support for mothers to develop improved small-scale farming and gardening to produce nutritious foods for consumption and for sale, as well as social acceptance of the programme. In addition, other respondents from community associations said that the weak ownership of activities by the sectors in their annual action plans and the low internal funding were considerable challenges to the sustainability of the programme.

Lessons learned from the decentralised implementation of the multisectoral nutrition programme

The regional triangulation workshop with implementing actors identified key lessons learned from implementation:

The establishment of the provincial multisectoral nutrition coordination platform under the leadership of the high commissioner was a catalyst for multisectoral governance. The high commissioner’s position, which is the highest political position and super head all sectors at the provincial level, brought together the key sectors around the platform to create a unifying framework. The clarification of the roles of the sectors in the implementation was important. The creation of a common vision was a challenge, but the mobilisation of sectors around a common goal with each sector having its own role successfully unified the sectors.

The designation of nutrition champions at the local level to organise community dialogues around public awareness and advocacy were very helpful in eliminating food taboos.

The distribution of micronutrient powder and introduction of nutrition-sensitive interventions increased women’s participation in GASPA nutrition education sessions:

The GASPA community platform approach was a gateway to building multisectoral platforms. The diverse themes covered during the GASPA sessions and the variety of communication channels were appreciated by women.

Discussion

Facilitating factors and challenges of the implementation of multisectorality

The study provided a better understanding of the success factors and challenges of the implementation of a multisectoral nutrition programme at the community level based on a qualitative study in Burkina Faso.

The level of participation varied by sector, with little participation from the non-health sectors. This low participation of nutrition-sensitive sectors had a negative influence on the quantity and nutritional quality of improved food production. In addition, the multisectoral approach requires full sector involvement at all stages of the process from programme development to implementation(Reference Garrett and Natalicchio8,Reference Victora, Barros and Assunção26) .

The study showed a lack of collaboration between sectors, with a tendency for sectors to work in silos. This lack of intersectoral collaboration at the decentralised level is reflected at the central level, where each sector focuses on its sectoral priorities. Several factors could explain the lack of sectoral collaboration. First, the persistence of a sectoral vision of malnutrition can be observed(Reference Alpha and Fouilleux7). Nutrition is perceived as the sole responsibility of the health sector, and the other non-health sectors do not feel very concerned. This is the weight of the initial stowage, the historical anchoring of malnutrition, as malnutrition has historically been an issue that is placed in the hands of the health sector. Faced with this predominant sectoral logic, it is necessary to build a common understanding through the capacity building of actors in nutrition-sensitive sectors regarding multisectorality in nutrition, to explain to these actors that their roles are important and to prompt them to align the fight against malnutrition with their sectoral priorities(Reference Heikens, Amadi and Manary27). Burkina Faso is making efforts to integrate nutrition into the training programmes of agronomists in vocational schools(Reference Sodjinou, Thiamobiga and Tapsoba28).

Collaboration is sometimes influenced by the commitment to nutrition among sector managers and the mobility of the actors; for new actors who do not know what is happening on the ground, sometimes it is necessary to re-explain everything. The issue of financial incentives is a challenge, and mechanisms should be put in place to motivate sector actors to facilitate their participation(Reference Durlak and DuPre24).

The study also showed that the scopes of entry, targets and sector priorities are not the same across sectors, which creates obstacles in the implementation of a multisectoral approach. These results corroborate those of studies carried out in Cambodia, Malawi(Reference Muehlhoff, Wijesinha-Bettoni and Westaway29,Reference Rawat, Nguyen and Ali30) , Bangladesh, Cambodia, Ghana, Mozambique and Nepal(Reference Komatsu, Malapit and Theis31). The differences in geographic targeting strategies by sector could be related to the tools used that result in the identification of different priority areas.

The low coverage of nutrition-sensitive interventions is a hindrance to the provision of a multisectoral package. However, as one author observed, the integration of interventions is the backbone of multisectorality(Reference Fajardo32). In addition, nutrition-sensitive interventions, by helping women engage in their own farming or livestock activities, allow women to link ‘theory to practice’ to improve food diversification(Reference Muehlhoff, Wijesinha-Bettoni and Westaway29,Reference Ismail, Immink and Immink33,Reference Kennedy34) .

The model of the Passoré provincial multisectoral platform for nutrition coordination is a good example that has made it possible to mobilise and unite the different sectors around multisectorality. However, with the multiplicity of coordinating frameworks and the overlap of the multisectoral nutrition coordination platform with the Provincial Food Security Council, it is necessary to consider whether the link between these two provincial coordination frameworks calls for their merger in order to increase the synergy of their actions(Reference Alpha and Fouilleux7,Reference Pelletier, Gervais and Hafeez-ur-Rehman35) . For increased multisectorality, it also seems necessary to reinforce the integration of nutrition into the frameworks of communal dialogues(Reference Ouedraogo, Doudou and Drabo17).

In terms of monitoring and evaluation, the obstacles observed could be explained by the low level of education of CHW and the lack of a decentralised multisectoral nutrition information platform such as the National Information Platform for Nutrition (NIPN). Improving the quality of routine data would strengthen the use of routine data as scientific evidence to better guide decision-making(Reference Tumilowicz, McClafferty and Neufeld21,Reference De Kadt36) .

The absence of a social accountability mechanism could be explained by the lack of a culture of accountability. However, the establishment of a social accountability platform would help improve the quality of services and solve some of the implementation difficulties(Reference Haddad, Achadi and Bendech37).

The urgency linked to the growing insecurity due to terrorist attacks in recent years is jeopardising the implementation of programmes in these areas around the Sahelian band and necessitates the development of new innovative strategies for adaptation to ensure that people have access to integrated multisectoral nutrition services(Reference Field38). In terms of sustainability, the programme offers guarantees of sustainability through strong community ownership, knowledge and changes in practices. This sustainability could be further strengthened through actions aimed at improving the uptake of interventions by sectors, the institutionalisation of the programme with the full involvement of CHW recruited by the state and the development of a strategy for mobilising local resources(Reference Pinto and Slevin25).

Recall bias was observed in relation to respondents’ recalling the details of certain events during the individual interviews. The triangulation of sources minimised this bias. Some key informants were not available at the time of data collection. In addition, there is a rapid staff turnover in public sectors and some participants were new on their respective position. As such, they have not been always participating in multisectoral implementation, limiting their knowledge and experience of the challenges and success factors. Also, the study was cross-sectional based on perceptions of implementing partners, a participatory observation with an immersion of researchers during several years would allow a better observation of the stakeholder dynamics.

Despite this limitation, this study adds to the growing literature on multisectoral planning and coordination. It is one of the first studies in sub-Saharan Africa to investigate the success factors and challenges of implementing a multisectoral nutrition programme at the community level. It has provided insights and identifying on news enabling factors for the delivering of multisectoral nutrition interventions at community level, including: (i) the importance of the model of GASPA community-based platforms as gate way to multisectoral implementation; (ii) the role of advocacy work of nutrition champions and (iii) the contributions of the provincial multisectoral nutrition coordination platforms.

The results of this study confirm certain barriers in the multisectoral nutrition planning at the national level(Reference Alpha and Fouilleux7,Reference Ouedraogo, Doudou and Drabo15,Reference Pelletier, Gervais and Hafeez-ur-Rehman35) : (i) low involvement and participation of certain sensitive sectors, (ii) verticality or working in silos, (iii) leadership conflicts between sectors and (iv) problem of mobilising endogenous resources.

Some barriers also corroborate those already identified in other studies conducted elsewhere at the decentralised level(Reference Muehlhoff, Wijesinha-Bettoni and Westaway29,Reference Rawat, Nguyen and Ali30,Reference Fajardo32) : (i) divergence in targeting approach between sectors, (ii) lack of incentives financial and (iii) lack of intersectoral convergence.

New specific obstacles to the delivery of multisectoral interventions at community level were identified in relation to previous knowledge include (i) absence of conventions with the non-health sectors; (ii) insufficient definition and clarification of the roles and expectations from different sectors; (iii) agenda conflicts between sectors, (iv) lack of technical skills among community workers; (v) weak ownership of activities by the sectors in their annual action plans; (vi) low coverage for nutrition-sensitive interventions; (vii) multiplicity of coordinating frameworks; (viii) absence of a multisectoral monitoring system and social accountability mechanism and (ix) insecurity context.

Policy and programme implications for programme planners and implementers

In view of the barriers observed, we propose the following strategies to improve the quality of the implementation of multisectorality:

Strengthen collaboration and coordination between health and non-health sectors by (i) boosting the functioning of multisectoral coordination platforms, (ii) strengthening the capacities of the actors for leadership and multisectoral coordination, (iii) formalising partnershipsto support the contribution of each sector and (iv) establishing financial incentive mechanisms to strengthen the participation of sectors.

Build the capacity of implementing actors regarding multisectoral approaches to nutrition as well as the technical aspects of implementing nutrition-sensitive interventions.

Harmonise targeting approaches or identify a common intersectoral targeting strategy with a single starting point, such as the GASPA community platforms.

Mobilise substantial resources to ensure that the full intervention package will cover a significant proportion of the beneficiaries.

Improve the geographical convergence of interventions and the coverage of beneficiaries with the intervention package to maximise nutritional impact.

Advocate for the integration of nutrition budget lines in sector action plans.

Establish a social accountability platform and a multisectoral information system to guide decision-making.

Support the advocacy work of nutrition champions.

Conclusion

The study helped to improve the understanding of the facilitating factors and challenges of implementing a multisectoral nutrition programme at the community level. However, the successful operationalisation of multisectoral programmes requires actions that address the key barriers identified to enable sectors to work together better and offer a more integrated package of services to the most beneficiaries to enhance the nutritional impact. Despite some limitations, the study results identified important lessons and programme implications that can be used to improve the effectiveness and impact of future multisectoral nutrition programmes.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank the association SEMUS, UNICEF and FAO for their generous contributions in the realisation of the study. The authors also thank the different categories of programme implementers in the three districts for their participation in the study. Financial support: The author(s) disclose the receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: the implementation of the multisectoral nutrition programme was funded by UNICEF. Conflict of interest: None declared. Authorship: O.O. led the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data and drafting of the article. M.H.D. participated in the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data and revision of the article. K.M.D. participated in the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data and revision of the article. M.K. participated in analysis and interpretation of the data and revision of the article. D.C. participated in analysis and interpretation of the data and revision of the article. C.M. participated in analysis and interpretation of the data and revision of the article. D.S. participated in analysis and interpretation of the data and revision of the article. N.M.Z. participated in analysis and interpretation of the data and revision of the article. P.D. participated in the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data and revision of the article. All authors contributed to the development, review and approval of the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the National Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Health’s (MOH). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S136898002000347X