Adolescents (10–19-year-olds) formed almost a quarter of The Gambian population in 2015(1), a proportion projected to increase(2). The Gambia, like other low- and middle-income countries, suffers from the triple burden of malnutrition(3), namely conditions of undernutrition such as stunting, co-existing with conditions of overnutrition, including overweight and obesity, and of micronutrient deficiencies including Fe deficiency(4). Having survived the highly vulnerable infectious disease stage of childhood(5), adolescents are often deemed healthy in many low- and middle-income countries including The Gambia despite still being at risk. Nonetheless, nutrition research has mainly focused on pregnant women, neonates and children under 5 years(6). This has left a knowledge gap around adolescent health, with data largely limited to anthropometry and anaemia status from either nationwide surveys(7) or region-specific research studies(Reference Schoenbuchner, Johnson and Ngum8–Reference Ward, Jarjou and Prentice12). What shapes adolescent nutrition is critical to understand in this community, given the potential triple benefits of interventions during this period on: improving contemporary health; long-term health and the health of future generations.

The determinants of adolescent malnutrition are multi-faceted. Delayed, stunted growth and impaired development may arise from suboptimal nutrition(Reference Salam, Hooda and Das13). Protein-energy malnutrition is rated high amongst the causes of deaths in children and adolescents(Reference Kyu and Pinho14). Many low- and middle-income countries are shifting away from their traditional diets, adopting convenience foods(15). Increasing rates of overweight and obesity among adolescents are related to immediate and long-term risks of developing non-communicable diseases (NCD)(Reference Koplan, Liverman and Kraak16,Reference Lloyd, Langley-Evans and McMullen17) . Also, whilst high proportions of adolescents from few West African countries do <60 min of moderate-to-vigorous-intensity physical activity daily, below the WHO recommendations on physical activity for health; there is no data on physical activity of any age group in The Gambia(18). Additionally, adolescence is a phase of the life course marked by increasing autonomy, although in many contexts, including The Gambia, opportunities for autonomy are experienced differently by young women and men(Reference Kaplan, Forbes and Bonhoure19–22).

Existing international and public health organisations focus on the sexual and reproductive health of women living in sub-Saharan Africa, including adolescent girls, but have failed to prioritise adolescent nutrition(23,24) . Rather, it forms an integral, albeit neglected, part of the health and nutrition policies of The Gambia. These policies are focused on reducing the incidence of diet-related NCD and improving the nutritional status of the socio-economically deprived and nutritionally vulnerable groups(24,25) . Simultaneously conducting research and implementing interventions on adolescent diet and physical activity may help realise the triple benefits of investing in their nutrition. As emerging adults, adolescent nutritional status is significant in breaking intergenerational cycles of malnutrition and growth failure(Reference Akseer, Al-Gashm and Mehta26). In The Gambia, stunting is significantly higher in rural children under the age of 5 years and rural inhabitants are at heightened risk of malnutrition from food insecurity emanating from unpredictable harvests(27). Understanding the perceived drivers of adolescent dietary and physical activity patterns within this context will be important for informing future health programmes and interventions. The way to understand such perceived drivers is to listen to the perspectives of adolescents and their caregivers. As part of the Transforming Adolescent Lives through Nutrition (TALENT) collaboration(28) (Barker et al., this issue), the current study took a qualitative approach to explore adolescents’ and caregivers’ perceptions of the factors influencing adolescent diet and physical activity.

Methods

Setting, research design and participants

The study was set in six rural villages of the Kiang West district of The Gambia (latitude 13oN, longitude 15°W), West Africa. Kiang West is located approximately 160 km from the capital Banjul. It covers an area of 750 km2, has a population size of approximately 15 000(Reference Hennig, Unger and Dondeh29) and mainly comprises subsistence farmers, many of whom undertake a small amount of commercial groundnut farming during the annual rainy season (June–October). These are predominantly Muslim communities, who live together in extended family compounds. Most compounds do not have access to improved sanitation and electricity, but community taps and water pump wells are available. The illiteracy rate is high, at 53 % for women and 40 % for men(7); education is via either Quranic or English-medium schools, or Quranic followed by English-medium schools.

Participants were selected by purposive sampling from the Keneba Demographic Surveillance Study Database(Reference Hennig, Unger and Dondeh29), considering the study eligibility criteria (i.e. age and gender). Contextual data were gathered via a cross-sectional survey focusing on adolescent’s height, weight, derived rates of stunting, BMI, and overweight and obesity. It included data on parental schooling, employment status, household assets and amenities, adolescents’ dietary diversity(30) and access to digital technologies (Fall et al., this issue). From the eighty respondents, a sub-sample of forty adolescents were invited to participate in a Focus Group Discussion (FGD). The sample was stratified by age, gender and generation. Recruitment and consent of participants were conducted by experienced field workers, who explained the study to participants in their native Mandinka language using a participant information sheet. Separate information sheets and consent forms for caregivers and adolescents were generated, explaining the purpose, process and potential outcomes of the study including issues of anonymity, confidentiality and the right to withdraw at any stage. Caregivers gave written consent for themselves and their child. Adolescents provided written assent for their own participation.

This paper focuses on the outcomes of the qualitative work, using some of the quantitative data for context. FGD were chosen as the most appropriate data collection method to obtain insights into adolescents’ experiences and a sense of social norms arising from group discussion(Reference Krueger and Casey31). Data quality focused on the depth and quality of interaction amongst participants, and adequacy of the sample for addressing the research questions. Data were generated via six FGD, each comprising ten participants. Designed to capture a diverse range of experiences, the groups included: girls (aged 10–12 years), boys (aged 10–12 years), girls (aged 15–17 years), boys (aged 15–17 years), mothers and fathers. FGD were conducted in a research room at the MRCG at LSHTM Keneba Field Station by I.C., M.B.M. and R.E.J. I.C. and M.B.M. were fluent in Mandinka and familiar with the context, having worked with the MRCG for many years. I.C., who had previous experience of conducting FGD, was the facilitator; M.B.M. together with R.E.J. were observers. Prior to the main data collection, two pilot FGD were conducted with six boys (11–13 years) and eight men caregivers to assess feasibility and inform on the format of future sessions.

Data collection

FGD were held during July 2018, with two conducted per week. Discussions were recorded using a digital voice recorder (Olympus VN-541PC). A semi-structured FGD guide was designed (see supplementary information for details of the main topics and questions) to explore qualitatively perceptions of the factors influencing adolescent diet and physical activity behaviour in this community. During each FGD, the researchers used creative methods to engage participants. For example, adolescent and caregiver participants were given fifty laminated photos of commonly available and consumed foods in Kiang West. The photos were spread on a table, and participants were asked to group the foods according to how beneficial they felt they were to their health. The food sorting activity was allocated 10 min.

Prior to starting the FGD, participants were assured of the confidentiality of any data generated (and the limits to confidentiality). Their anonymity and safety were guaranteed throughout all phases of the research. They were encouraged to express themselves unreservedly, whilst also respecting the views of others. FGD were conducted in the mornings and lasted between 40 and 100 min.

Data analysis

All quantitative data were imported into Data Desk 6.3 (Data Description Inc.)(32) to describe simple summary statistics. Audio recordings in Mandinka were directly translated and transcribed into English, since Mandinka is not a written language. The Gambian field researchers performed all the translation and transcription using a transcription device (Olympus AS-2400 Transcription Kit). Participants’ identities were anonymised and uniformly cited in transcripts as ‘P’.

Guided by Braun and Clarke’s approach(Reference Braun and Clarke33), the data were analysed thematically. To ensure accuracy, audio records were checked against the English transcripts. These transcripts were uploaded into the qualitative software package NVivo (version 12, QSR International Ltd)(34) and coded by R.E.J. Themes were inductively generated at first, and then, based on the research questions, a deductive approach was taken. A coding framework was developed in collaboration with the other studies that formed part of TALENT (Barker et al., this issue). Similar codes were organised into themes, aided by the use of cross-tabulations comprising major codes and case attributes. The coding was reviewed by P.H.J. and S.W. Based on the researchers’ interpretation of the data and themes, a thematic map (Fig. 1) was developed manually.

Fig. 1 Thematic map framework of the determinants of rural Gambian adolescent diet, physical activity and health

Results

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of those who completed the survey. Participants were all Muslim of low socio-economic background. All the adolescent participants had good diet diversity score with median >9 for all groups, and 100 % of adolescents had a score >5.

Table 1 Characteristics of the quantitative study participants*

* Data are reported as (n and %) for categorical variables; mean and sd for normally distributed data; and median (interquartile range – IQR) for skewed data. Diet diversity score is reported as median (IQR), n scoring ≥ 5.

Very few homes had an electricity supply, and only 4·5 % of the older boys had an electric fan, but radio possession was common. None of the households owned a car. Fall et al., this issue, give a comprehensive report of the quantitative data across the sites comprising the wider TALENT study.

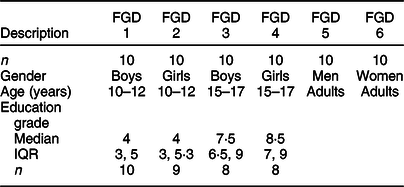

Forty adolescents from the quantitative study and twenty caregivers participated in the FGD. The sample attributes are illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2 Attributes of the focus group discussion (FGD) participants

Figure 1 details the major themes that emerged from the FGD. For many participants, economic factors and the local environment were interrelated in determining adolescent food availability and variability in physical activity. Similarly, many pointed to the relationship between economic, environmental, social and cultural factors in driving ambitious plans for social and cultural activities.

Knowledge of the links between diet and health

Many participants demonstrated good awareness of the association between diet, health and physical activity, depicted as the outer framework of Fig 1. In all of the FGD, participants were able to discuss the health benefits of the specific food groups and/or physical activity:

‘These are garden produce, when they are eaten, can help protect the body from many minor ailments’ (woman caregiver, FGD6).

‘[The physical activity we do] give us energy, power or strength’ (younger girl, FGD2).

Across the FGD, the majority of participants displayed more advanced nutritional knowledge associating certain diseases with diet.

‘It [Salt seasoning] … also causes high blood pressure…’ (man caregiver, FGD5).

‘Sugar is not good [for health], it causes diabetes’ (older girl, FGD4).

However, there were some differences in the nature of that knowledge between groups. Younger participants and caregivers tended to articulate a more basic understanding:

‘If you mix them [milk and candies], it is going to cause sickness’ (younger boy, FGD1).

In contrast, only older boys and girls displayed a more in-depth understanding. They tended to speak in more detail about the nutritional benefits of certain foods:

‘… vegetables, … have vitamins, vitamin C is good in the body. All these things…, if you lack one of them…, you have disease.’ (older boy, FGD3).

However, some discussions implied that the quality of nutrition knowledge of many participants was not entirely evidence-based, but revolved around some misconceptions:

‘Milk, … is good for men who smoke cigarettes, … it cleans their lungs’ (older girl, FGD4)

‘Chocolate … it can cause liver problem, spoil the liver’ (man caregiver, FGD5)

‘… the running they do is good as it makes their blood flow well…’ (woman caregiver, FGD6)

All participants showed understanding of the association between dental health and sugary foods.

‘Biscuits and chocolate can cause toothache’ (woman caregiver, FGD6)

Despite concerns about adolescents’ diet and physical activity levels, the FGD highlighted that all adolescents had some knowledge of the relationship between health, diet and physical activity. Being in relatively higher education (Table 2), older adolescents generally had a more in-depth understanding and were able to articulate the relationship between specific food groups and nutrients.

Economic factors driving adolescent diet

All participants perceived household wealth variations, along with changes in the affordability of different foods, to be an important driver of adolescent diet. They suggested many were unable to regularly afford nutrient-rich foods. Rather they were restricted to monotonous diets comprising nutrient-poor staples:

‘When there is no money, we don’t eat it [butter]; [We eat] porridge or heated rice’ (younger boys, FGD1)

The hot climate, coupled with lack of refrigeration, hindered preservation of fresh produce. However, adolescent boys and men caregivers felt that even for perennial nutritious foods like beans, their consumption depended on affordability:

‘You can eat [beans] … for up to a week … if you have the means, it requires affordability’ (man caregiver, FGD5).

Moreover, the majority of women caregivers indicated that the receipt of remittances impacted on the foods consumed:

‘… what you used to have [in terms of diet] can now change if you have more income’ (woman caregiver, FGD6)

FGD participants, therefore, reinforced a common perception that food affordability directly affects adolescent diet and highlighted indirectly the link between diet and health. Increased household wealth through remittances was seen only by women caregivers to shape the diets of adolescents.

Social and cultural factors affecting diet

Participants outlined a range of social and cultural influences on adolescent diet, which mainly comprised familial decision-making habits. A large proportion of participants perceived mothers as the main decision makers regarding the major meal of the day, followed by fathers. Nonetheless, whilst mothers may determine what the meals comprise, limited resources restricted choices.

‘Those who cook [mothers] [decide what is eaten at home]’ (woman caregiver, FGD6)

Most participants were satisfied with mother-led decision-making; only women caregivers posited adolescents’ dislike of some meal decisions, which often resulted in food wastage. Some of the men caregivers felt the need for a more autocratic approach in the face of a lack of dietary choice:

‘… if you cannot get what they demand, you force them to eat what is available …’ (man caregiver, FGD5)

A minority of participants, mainly the younger girls and women, spoke of the limited role adolescents played in choosing meal options:

‘Children can say: mum, today this is what we want to be cooked.’ (woman caregiver, FGD6)

Shaped by tradition and family size, gendered familial hierarchies in food sharing practices were reported by all caregivers, older boys and young girls to influence adolescent diets. Where this practice existed, adolescent boys often benefitted from more nutritious foods than girls.

‘… mostly the very elderly are dished separate meal …sometimes joined by their grandchildren; … adolescent males join their fathers and females their mothers.’ (man caregiver, FGD5)

Moreover, most participants believed festivals, birth and wedding ceremonies had a sporadic influence on the nature of adolescent diets:

‘… more ‘benachin’ (one-pot dish of rice, oil stew and meat or fish, and vegetables) are cooked.’ (older girl, FGD4)

At such ceremonies, highly energy-dense foods are consumed, including carbonated drinks high in sugar. Conversely, a small number of participants, mainly older boys and women caregivers, spoke of the consumption of salad during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan.

‘During Ramadan, … they prepare fast breaking foods like salads …’ (woman caregiver, FGD6)

Outside of the home environment, participants suggested that some adolescents were able to access nutritious foods at school, but this was not universal. Rather, nutrient-poor foods were readily accessible from street vendors in close proximity to schools. Such foods included local and/or cheap fruit-flavoured drinks high in sugar and chemical additives or deep-fried snacks.

‘… [During break times at school], sometimes I go to look for food’ (older boy, FGD3).

In the main, FGD participants felt that the social and cultural influences on adolescent diet included mothers’ decision-making over domestic issues, fathers’ autocracy and hierarchical family structures, the nature of food available in schools, and, to a lesser extent, cultural and religious events and practices. Adolescents able to purchase items from street vendors appeared to have some limited autonomy over their diet.

Environmental influences on diet

All participants pointed to the influence of seasonality on rural adolescent diet and the abundance of nutrient-rich green leafy vegetables in the rainy season:

‘During the rainy season, the types of foods we have are leaves like ‘kucha’(sorrel), these are more available during the rains…’ (older boy, FGD3).

A few participants, mainly younger boys and older girls, spoke of the consumption of fruits such as mangoes common in the rainy season, and oranges and cashews abundant in the dry season:

‘We eat [mangoes] everyday if we have them, and cashews when available’ (younger boys, FGD1).

Short sojourns to urban areas also influenced adolescent’s diets, with opinion split between participant groups. The younger boys and girls and women caregivers perceived a dietary change when in urban areas:

‘F: …What do you eat in Sukuta (urban) that you don’t eat in Manduar (village)?’

P: Bread and tea

P: Chips

P: Milk powder.’ (younger boys, FGD1)

In contrast, older boys and girls and men caregivers believed there were little or no changes in diet between rural and urban areas:

‘The Gambia is all one food … rice only.’ (man caregiver, FGD5).

Although urban environments were perceived to expose adolescents to more junk foods, their diet at home was also rich in fats and oils, salt and sugar. Hence, many participants perceived the association between consumption of these foods with hypertension, diabetes and poor dental health.

Awareness of the links between physical activity and health

All participants gave examples of physically active tasks that adolescents do as part of their daily chores including farming and food production. Participants also demonstrated knowledge of the link between physical activity and good health:

‘… the running they do is good as it makes their blood flow well …’ (woman caregiver, FGD6).

Older girls commented on the effects of sedentary behaviour:

‘Inactivity after eating fully is not good for health’ (older girl, FGD 4).

Despite the general lack of data on physical activity, for many participants, gardening and farming constituted a key form of physical activity, in addition to contributing to local food production. The perception of the link between health and physical activity and knowledge of health benefits was a motivator for physical activity. The majority of participants concurred that physical activity was good for health, strong bones and boosted power, whilst women caregivers conceived it to strengthen joints. Younger boys associated physical activity with disease prevention.

Perceptions of cultural, economic and social influences on adolescent physical activity

Cultural practices, particularly the popularity of music and dance, were commonly regarded as important factors influencing adolescent physical activity. According to men caregivers, adolescents organised parties and danced during school holidays and ceremonies. Women caregivers also commented that at the football field, young girls grouped themselves, clapped and danced as well as during breaktime at school:

‘When there is music, we dance.’ (younger boy, FGD1).

‘We beat the drum and dance.’ (older girl, FGD4).

Despite the lack of availability of digital technologies (Table 1), with the exception of battery-powered radios, their potential influence on sedentary behaviour was mentioned in all groups, highlighting the link between social factors, physical activity and health in the thematic map (Fig. 1). Caregivers spoke of, what they felt was, adolescents’ growing interest in watching television and using mobile phones:

‘During weekends and in the evenings, we watch ‘Mannu’ (Indian film) on Joy Prime channel’ (older girl, FGD4).

Although with relatively little access to digital media given, only 5·3 % younger girls and 13·6 % older boys reported possessing a television in the household (Table 1). The time spent using digital technologies, for instance the collective watching of television, was still a concern amongst participants. Many participants perceived frequent use of media devices to reduce physical activity, whilst dancing, field and breaktime activities improve physical activity of adolescents.

Environmental factors affecting physical activity

All participants provided examples of the ways in which physical activity featured in rural adolescents’ lives as a consequence of the natural environment setting. For example, all travelled to school by either on foot or by bicycle, with younger adolescents tending to do the former:

‘Some go by bicycle and some on foot to school’ (man caregiver, FGD5).

A further example was household chores including the collection of water from community taps and wells, as majority of homes do not have piped water to the house (Fall et al., this issue). Sometimes wheelbarrows or bicycles would be used to help carry water drums:

‘After lunch, I fetch water and if there is cooking for the evening, I do it, and sweep’ (older girl, FGD4).

Men caregivers also mentioned adolescents’ involvement in activities such as the repair of fences and the clearing of backyards, while the older boys indicated that they fetched sticks for fencing works, firewood and shepherding goats. Women caregivers underscored that pounding, washing dishes and laundry were activities done by adolescents, the latter common at weekends:

‘…those who have pounding would do that’ (woman caregiver, FGD6).

Last, the majority of participants had the opinion that seasonality appeared to affect adolescents’ physical activity patterns. It was indicated that young and older adolescents clear the farm in the rainy season prior to sowing groundnuts and acting as shepherds.

‘We go to the bush during the rains, for working, clearing the farm, planting groundnuts’ (younger boys, FGD1).

The activities described above have varying degrees of intensity. Enjoyable but less strenuous activities include dancing, walking, cycling to school and household chores. Fetching water, gardening and farming may be classified as moderate- to high-intensity activities. The availability of outside space shaped opportunities for physical activity. Football was a frequently cited example of recreational physical activity. Some women caregivers and older girls insinuated that this was dominated by boys with girls were side-lined and confined supporting the boys:

‘They [girls] at the field support football teams’ (woman caregiver, FGD6).

Adolescent boys’ supposed control of field spaces was a gender norm in this setting. As a result, girls had little opportunity to use such spaces for their own recreation. All these environmental activities are believed to form part of adolescent physical activity in the rural context, depicted as the link between the natural environment and physical activity of adolescents in the thematic map (Fig. 1).

Discussion

We have described here, from the perspectives of adolescents and caregivers, factors influencing adolescent diet and physical activity in rural Gambia. To our knowledge, this is the first work of this kind conducted in this context. A knowledge of the link between diet, physical activity and health was expressed by majority of participants, highlighted in the thematic map (Fig. 1). The older adolescents particularly possessed superior knowledge of nutritional benefits of foods, probably gained from attending upper basic schools (Table 2), where the curriculum consists of general science education including an introduction to food. In contrast, a significant proportion of participants’ nutrition knowledge lacked an evidence-base reinforcing the need for effective, intergenerational nutrition education. Hence, the separate theme of nutrition knowledge in the thematic map needs further research. Nonetheless, the heightened awareness of many participants (through the radio, local health personnel, community outreach and word-of-mouth) of the relationship between diet and high blood pressure might be a response to the increasing diagnosis and prevalence of hypertension in the rural adult population(Reference Cham, Scholes and Fat35). In the same environment, high odds of hypertension in young lean rural adolescents is also a cause for concern(Reference Jobe, Agbla and Prentice36). Furthermore, diabetes prevalence is on the rise(37–Reference Rolfe, Tang and Walker39) and is diagnosed annually in Gambian children and young adolescents(Reference Patterson, Guariguata and Dahlquist40).

Likewise, an association between eating sugary foods and dental health is well known, generating the relatively minor but novel theme of dental health in Fig. 1. Dental caries have very high incidence among Gambian adolescents(Reference Adegbembo, Adeyinka and George41,Reference Kosovic and Nilsson-Andersson42) . This high risk and the associated discomfort of toothache may explain adolescents’ preoccupation with dental care. Whilst chewing sticks and imported toothbrushes and pastes are available, there is, for many, limited access to dental services and low fluoride content in drinking water in some areas of The Gambia(Reference Jordan, Schulte and Bockelbrink43). Moreover, health is borne to be associated with economic conditions; an association clearly demonstrated in the thematic map via the joint theme of diet. Affordability seemingly influencing the dietary habits of rural Gambian adolescents is consistent with reports by The Gambian government and UNICEF(27) and from other settings in sub-Saharan Africa(Reference Mukhayer, den Borne and Rik44). Also, remittances purportedly improving food security and dietary diversity is similar to other settings, for example, Nigeria(Reference Akerele and Odeniyi45).

Perceived social and cultural factors emerged as a particularly salient theme shaping adolescent diet. This theme is directly and indirectly interrelated to food availability through the natural environment and economic power. Decisions about meals were considered to be driven by availability, and then familial hierarchies and gendered decision-making practices, followed by cultural and religious ceremonies. Women caregivers’ role in decision-making around meals has been described in black African and Caribbean children in London, UK(Reference Rawlins, Baker and Maynard46). This opinion is also supported by the reports of men’s low participation in food preparation. Gender segregation in food consumption is a long-standing tradition in Gambian villages, where fathers are treated as household leaders and served first with the best part of the dish or better quality foods(Reference Mwangome, Prentice and Plugge47,Reference Pérez and García48) . Although this practice is perceived to be changing, some participants confirmed it still exists, in which case adolescent boys might benefit from sharing more nutritious foods with their fathers. Moreover, the World Food Programme, in partnership with the government’s school feeding programme, only exists for the lower basic schools(49). Consequently, older adolescent students are deprived of this nutritious systematic feeding programme.

The seasonal availability of fruits, vegetables and nuts, denoted by the major natural environment theme (Fig. 1), as a perceived driver of adolescent diet, has been quantitatively defined during analysis of seasonality of micronutrients in this region(Reference Bates, Prentice and Paul50). Comparable to neighbouring Senegal, the tendency for the adolescent diet to become monotonous is, to a large extent, explained by the seasonality of some foods like mangoes(Reference Fiorentino, Landais and Bastard51). Moreover, opinions differed about diet variability between the rural and urban areas. The development of The Gambian South Bank Road (a major trans-Gambia highway) ushered in improved access to imported food commodities in the region, with the creation of local shop vendors. Thus, the themes natural environment and economic factors in Fig. 1 are perceived to be interrelated in influencing diet and indirectly health.

Moreover, analysis of the FGD highlighted the connection between the natural environment, economic factors and the nature of physical activity undertaken by adolescents. These groups of rural adolescents felt that they had high levels of physical activity inherent in living in a rural subsistence farming community. When access is available to resources such as televisions, this reduces physical activity in a similar way to high-income settings(Reference Sandercock, Alibrahim and Bellamy52). The role of other daily household chores in contributing to physical activity has been highlighted in West African Serer adolescents who reported pounding millet, an arduous chore completed by girls(Reference Benefice, Garnier and Ndiaye53). Supposedly, seasonality as a component of the natural environment was discerned to discreetly shape the frequency and intensity of routine adolescent physical activity by priority apportioned to gardening or farming.

The findings from this qualitative study highlight important issues to inform further research on the health and nutrition of adolescents in this setting. Specifically, the consistent commentary that financial constraint shapes choice, with poverty impacting on both dietary diversity and food security, is a key finding. As the majority of the adolescent groups were in education, school feeding programmes to help diversify foods for rural poor adolescents in both lower and upper basic schools may be of benefit, alongside reviewing the health and nutrition education content of the school curriculum to impart deeper nutrition knowledge. Government rapid action on socio-economic status at the individual, household and community levels via investments in sustainable diversified large-scale mechanised agriculture, revitalising the fishing and local manufacturing industries and improving social security and housing conditions could prove effective.

Access to open land and playing fields is a motivator for adolescent physical activity, a finding consistent with previous reports from high-income settings(Reference Davison and Lawson54). However, sporting activities were generally dominated by boys. Supporting adolescent physical activity through maintaining spaces with sport amenities would impact on recreational physical activity for both boys and girls. For adolescent girls, the pathway to impact can include recreational dance classes or a designated space for girls’ team sports.

The strengths of the current study include the rigorous methodology, participants’ engagement, the time allowed for discussions that yielded in-depth information, and the available supportive network of qualitative researchers. The study involved caregivers of adolescents which provided an opportunity to explore and obtain various perspectives about diet and physical activity. Also, the FGD were conducted by experienced local research staff, with local knowledge and good community relations. Limitations include problems common to qualitative research, such as the dominance of some individuals in discussions and the reluctance of some members to participate or elaborate on their responses, which the facilitator tried to mitigate. Also, deeper probing questions could have yielded more data.

In conclusion, this paper has demonstrated that the rural Gambian adolescents and their caregivers involved in this study understood the link between diet, health and physical activity. Perceived drivers of adolescent diet and physical activity included a variety of economic, social and cultural factors, underpinned by the local environment. Interventions need to address these interrelated factors, including misconceptions regarding diet and physical activity that may be harmful to health.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful to all adolescents and caregivers who participated in the study. We also thank the drivers, field and data management teams at the MRCG at LSHTM Keneba field station. Financial support: This study was funded by a Global Challenges Research Fund/Medical Research Council pump priming grant (grant number: MC_PC_MR/R018545/1). Funding support was also provided by the MRC (Programme Numbers U105960371; U1232611351 and MC-A760-5QX00) and Department for International Development (DfiD) under the MRC/DfID Concordat. The funding agency was not involved in the study design, data analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: R.E.J.: Contributed to the study design, coordinated implementation of the study, collated and analysed all data, and wrote the manuscript. P.H.J.: Contributed to study design, provided qualitative research training, supervised the study, contributed to data analysis and interpretation, provided critical review and input to the manuscript. S.H.K.: Contributed to the study design, reviewed and contributed to drafting of the article. M.B.M.: Observed the focus group discussions (FGD), contributed significantly to data collection and translated and transcribed the audio data. I.C.: Facilitated the FGD, contributed significantly to data collection and translated and transcribed the audio data. L.J.: Provided advice, direction and support for the local implementation of the project. K.W. and S.E.M.: Contributed to the study design, adapted the standardised TALENT questionnaire to the Gambian context, supervised the implementation of the study, reviewed and provided critical and substantial input and revision to the manuscript. C.F.: Contributed to the conception and design of the study and provided critical review of the manuscript. M.B.: Contributed to the study conception and design, provided qualitative research training, made substantial input to the data interpretation and reviewed the manuscript. S.W.: Provided qualitative research training, contributed to data analysis and interpretation, provided substantial critical reviews and input to the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving study participants were approved by the joint Medical Research Council Unit The Gambia at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine/Gambia Government Ethics Committee (SCC1590v2.2). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020002669