Food practices in the first year of life are important in the formation of children’s eating habits( 1 ). According to the WHO, breast milk must be the first and sole option during the first 6 months of life, followed by an appropriate complementary diet while maintaining breast-feeding until 2 years of age or more( 2 ). Research shows that breast-feeding support programmes have increased the rates of breast-feeding since the 1990s( Reference Labbok, Wardlaw and Blanc 3 ). In 1995, 34 % of children under 6 months received breast milk exclusively, while in 2011 the rate had risen to 43 %( 4 ). This increase was due to governmental incentives through programmes to protect, promote and support breast-feeding( 1 – Reference Labbok, Wardlaw and Blanc 3 ). Nevertheless, this percentage is still far from the recommendation( 1 ).

In the global scenario, only 60 % of children from 6 to 8 months receive solid or semi-solid foods correctly for their stage of development, with inappropriate quality and frequency of complementary feeding possibly leading to nutrient deficiencies( 4 ). It is important to consider that in this stage of life, children usually leave the exclusive family setting and start attending nurseries. Therefore, the nursery becomes an important partner in the appropriate introduction of complementary feeding, considering that children will have most of their meals there( Reference Ramos, Santos and Reis 5 , Reference Cervato-Mancuso, Westphal and Araki 6 ). In this regard, food and nutrition education (FNE) is an interesting strategy to improve feeding practices in the first years of life, as it has shown a significant effect on the growth of children up to 24 months( Reference Walsh, Kearney and Dennis 7 , Reference Imdad, Yakoob and Bhutta 8 ).

Despite these benefits, FNE is rarely performed in nurseries and kindergartens. Goulart et al.( Reference Goulart, Banduk and Taddei 9 ) highlighted the importance of this setting for educational processes that target children and their families, as well as the consequent demand for trained educators to encourage healthy eating practices. The lack of adequate FNE in nurseries and schools is associated with nutritional deficiencies, such as anaemia, and lower prevalence of breast-feeding( Reference Goulart, Banduk and Taddei 9 ).

Thus, the aim of the present study was to analyse the effectiveness of different interventions based on FNE for nursery professionals and the parents/guardians of infants.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

The present study was a non-randomized controlled intervention study conducted in public nurseries of a municipality in Brazil (Nova Lima, 87 400 inhabitants, 428·4 km2), located in the metropolitan region of Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais. The municipality has ten nurseries with approximately 202 students under 2 years of age (study population).

Research was conducted in 2015 with the parents, directors, supervisors, teachers and kitchen coordinators responsible for students enrolled in nurseries level I and II, which are the students under 2 years of age. Initially, the sample was analysed regarding demographic data (age and education of parents; sex, age, date of birth, telephone number and address of the students) through a questionnaire completed by the guardians of the children. Next, two different FNE interventions were implemented in two groups: (i) the control group (CG), which received a standard intervention consisting of written guidelines; and (ii) the intervention group (IG), which, in addition to receiving the information of the CG, participated in bimonthly meetings regarding healthy complementary feeding. The groups were divided according to the viability of the nursery for the meetings (face-to-face intervention).

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (CAAE 44107215.3.0000.5149).

Nutritional interventions

The themes of the interventions were selected from the main problems addressed in recent studies( Reference Caetano, Ortiz and Silva 10 – Reference Monterrosa, Frongillo and Cossío 12 ) and in national research( 13 , 14 ), as well as from the requirements of the nursery professionals and parents/guardians of the children. The Food Guide for Children under Two Years Old ( 15 ), the Primary Care Booklet No. 23 ( 1 ) and the guidelines of the National Strategy for Healthy Supplementary Feeding( 16 ), the Breastfeeding Network Brazil( 17 ) and the Breastfeeding Nurtures Network( 18 ) were used for the theoretical framework.

Five key messages were created to work on with the parents/guardians and nursery professionals, the themes being: breast-feeding, consistency of baby food, offering rejected foods again, healthy diet and foods to be avoided. The key messages were presented to the nursery professionals of the CG as posters arranged in accessible locations where these professionals spent most of their working hours. The posters contained brief, visually stimulating information that the professionals could read quickly and reinforce their interest in the themes.

Interventions with the parents/guardians of the CG consisted of reports with similar information to that of the posters, attached in the notebook of the students once per month. The student notebooks are the most common and efficient means of communication between the municipal nursery schools and the parents/guardians. The estimated average time of the CG interventions was 50 min, considering the approximate time required to read each activity.

The activities for the professionals of the IG consisted of four meetings of 8 h total duration on healthy complementary feeding, resulting from the key messages used in the CG. These meetings were performed by a nutritionist at the municipal nurseries, during the workday of the professionals. The interventions with the parents/guardians occurred in a similar way; however, the content was more succinct because most of the parents had jobs or did not have time, as observed in previous studies. The IG parent meetings had a total duration of 5 h.

Evaluation of nutritional interventions

The interventions were assessed differently for the professionals and the parents.

The shift of knowledge regarding the themes covered with the professionals was assessed using an adapted questionnaire( Reference Barros and Seyffarth 19 ) containing ten objective questions about breast-feeding and complementary feeding. Both groups answered the instrument before and immediately after completing the FNE activities. This questionnaire included personal information, such as age, education, experience in nursery schools, participation in any course on infant nutrition and whether the subject had a child, to check any possible association between personal experience and total correct responses. In addition to the nutritional intervention, the instrument contained a brief assessment of the course.

The effectiveness of the intervention with the parents was assessed according to the evolution of the food consumption of the children and any changes in beliefs, attitudes and intentions of the parents after eight months of nutritional intervention. Food consumption was evaluated using the adapted SISVAN questionnaire( 20 ) that the parents or guardians completed before and after the nutritional intervention. The Food Guide for Children under Two Years Old was used to analyse the questionnaire( 15 ).

The beliefs, attitudes and intentions of the parents in relation to certain eating behaviours were assessed according to the instrument proposed by Monterrosa et al.( Reference Monterrosa, Frongillo and Cossío 12 ) that uses a Likert scale with three levels of response for beliefs and attitudes and five levels for behavioural intention. The questionnaire was applied simultaneously to the food consumption questionnaire at the start of and shortly after the last nutritional intervention.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analysis of the data included calculation of frequencies and measures of central tendency and dispersion. The distribution of the quantitative variables was verified using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and the results were presented as mean and standard deviation for the variables with normal distribution and as median and interquartile range (IQR) for the non-parametric variables.

Before analysing the effects of the nutritional intervention, the CG and IG were compared at baseline. Student’s t test and the Mann–Whitney test were used for a simple comparison of means and medians, respectively, and the χ 2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the proportions. Considering the analysis of the evolution of the professionals’ knowledge after the procedure, ANCOVA was used to evaluate any changes in the mean number of correct responses to the questionnaire in each group. The change in correct responses was assessed using McNemar’s test.

The intergroup analysis of the professionals’ assessment in relation to the nutritional intervention was performed by comparing the medians using the Mann–Whitney test. Also, Spearman’s correlation and the Mann–Whitney test were used to compare the medians of correct responses for the non-parametric explanatory variables and qualitative variables, respectively.

Changes in the beliefs, attitudes and behaviour of the parents after the nutritional intervention were compared using Wilcoxon’s test and McNemar’s test. The intergroup analysis of food consumption was assessed using the χ 2 test or Fisher’s exact test, and the intragroup analysis was assessed using McNemar’s test.

The analyses were performed using the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 19.0 (Student Version), considering a level of significance of 5 %.

Results

A total of ninety professionals initially participated in the study (CG, n 50; IG, n 40). Of these professionals, three teachers (CG, n 2; IG, n 1) did not answer the questionnaire after the nutritional intervention, due to changing school.

Regarding the parents of the students, 202 (CG, n 102; IG, n 100) participated in the initial stage; seventeen (CG, n 5; IG, n 12) did not continue with the research because their child left the school and sixteen from the IG were excluded because they did not take part in any of the meetings. Thus, the final analysis totalled 169 parents (CG, n 97; IG, n 72).

Professionals at baseline and evolution after the nutritional intervention

All the participants were women, with a mean age of 44·7 (sd 9·2) years. It was found that 81·0 % had children, 60·0 % were teachers and 48·9 % had completed some type of specialization course. It should be noted that the study groups were similar regarding profession and education. The IG, however, had more experience working in nurseries than the CG (P=0·001) and presented greater attendance during the child nutrition course in comparison with the CG (P=0·016).

In terms of prior knowledge on breast-feeding and complementary feeding, there was no statistical difference in any of the responses when comparing the two groups at the baseline of the study (Table 1). The median of correct responses was 9·0 (IQR 5·0–14·0) questions (P=0·256). There was no statistical difference in the median of correct responses at baseline according to the presence of children (P=0·818), completion of the course on child nutrition (P=0·788), work experience in nurseries (P=0·144) and schooling (P=0·224). Of the IG, 32·5 % of the professionals participated in all the meetings, 39·5 % attended three meetings, and 9·3 % and 18·6 % attended two and one meeting, respectively.

Table 1 Evolution of the knowledge of the nursery professionals after the nutritional intervention on complementary feeding practices, intragroup and intergroup comparisons; Nova Lima, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil, 2015

CG, control group (received standard food and nutrition education in writing); IG, intervention group (received the same information as the CG and face-to-face meetings).

McNemar’s test was used for intragroup comparisons; the χ 2 test or Fisher’s exact test for intergroup comparisons.

aStatistically significant intergroup difference, P<0·05.

bStatistically significant intragroup difference in post-test, P<0·05.

The intragroup comparative analysis showed that the IG performed better on the questionnaire after the intervention than the CG, with a significant difference between the mean number of correct responses after the baseline adjustment (12·2 v. 10·7; P=0·001).

With respect to the type of food initially offered in complementary feeding and awareness that the child should be breast-fed until the age of 2 years or more, there was a significant increase in correct responses in both groups (Table 1). Among the incorrect responses, the majority of professionals believed that complementary feeding should be introduced with teas and juices (70·9 % at baseline and 30·2 % after the intervention) and breast milk should only be offered until the sixth month (47·8 % at baseline and 19·8 % after the intervention).

The professionals of the CG and IG had prior knowledge that complementary feeding should not replace breast-feeding and that certain foods, such as sugar, coffee, tea and canned foods, should not be offered in the first years of life. This knowledge remained unchanged in the post-test (Table 1).

The IG showed a significant increase in knowledge after the nutritional intervention in relation to the most suitable foods for complementary feeding (P<0·001), consistency (P=0·002), foods that should be offered at lunch (P=0·007), the correct age to introduce complementary feeding (P=0·039) and foods that help with iron absorption (P=0·039; Table 1).

Among the incorrect responses, the majority of professionals believed that soup was the most suitable food to be offered for complementary feeding. Foods prepared using the blender and the introduction of foods from 3 months (15·0 % at baseline) and 4 months (6·9 % after the intervention) were also frequent incorrect responses.

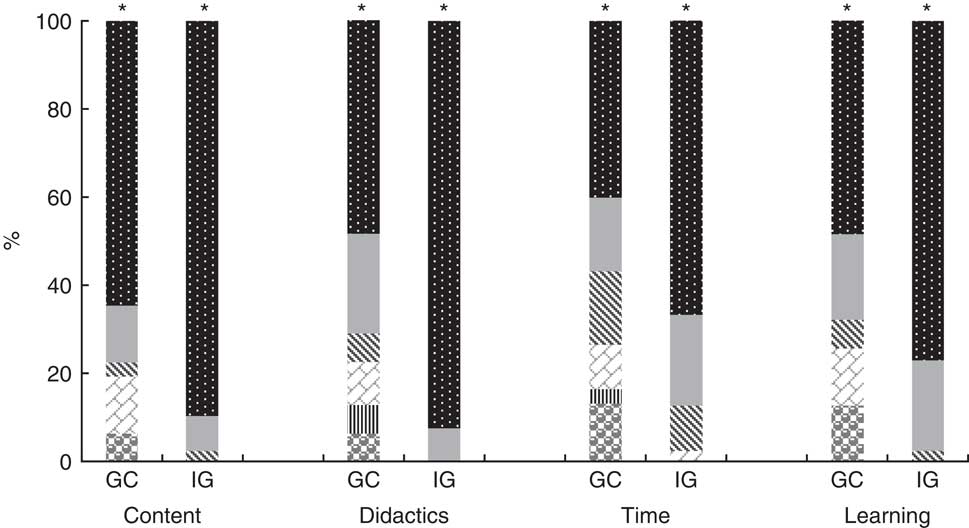

The IG reported greater learning and practical application than the CG (100·0 v. 57·9 %; P<0·001). Figure 1 shows the evaluation of the professionals regarding the content, didactics, time and learning provided by the course. This evaluation revealed statistically higher scores in the IG for all items (P<0·05).

Fig. 1 Intergroup comparison of the assessment of the nursery professionals in relation to the nutritional intervention on complementary feeding practices, considering scores from 0 to 5 (![]() , 0;

, 0; ![]() , 1;

, 1; ![]() , 2;

, 2; ![]() , 3;

, 3; ![]() , 4;

, 4; ![]() , 5); Nova Lima, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil, 2015. *Statistically significant difference (Mann–Whitney test), P<0·05 (CG, control group (n 50) received standard food and nutrition education in writing; IG, intervention group (n 40) received the same information as the CG and face-to-face meetings)

, 5); Nova Lima, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil, 2015. *Statistically significant difference (Mann–Whitney test), P<0·05 (CG, control group (n 50) received standard food and nutrition education in writing; IG, intervention group (n 40) received the same information as the CG and face-to-face meetings)

Children and parents/guardians at baseline and evolution after the nutritional intervention

Of the infants, 60·4 % were male with a median age of 14·4 (IQR 10·1–17·8) months. The median age was higher among participants of the CG (15·5 v. 12·7 months; P=0·009; Table 2). The median age of the mothers was 28·0 (IQR 23·0–34·0) years and the median age of the fathers was 31·0 (IQR 27·0–38·0) years. Most of the parents had finished secondary school (Table 2). There were no differences between the groups prior to the nutritional intervention.

Table 2 Sociodemographic characteristics of the children (<2 years) and their parents according to experimental group in the nutritional intervention on complementary feeding practices; Nova Lima, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil, 2015

CG, control group (received standard food and nutrition education in writing); IG, intervention group (received the same information as the CG and face-to-face meetings); IQR, interquartile range; BRL, Brazilian Real.

The χ 2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables; the Mann–Whitney test for the age comparison.

*Statistically significant difference, P<0·05.

The mothers exclusively breast-fed their infants up to the sixth month in 18·5 % of cases and 60·5 % of the children were exclusively breast-fed until the fourth month or less. The median breast-feeding duration was 135·0 (IQR 60·0–210·0) d. It was found that 48·3 and 28·7 % of the infants were fed baby food and honey/sugar before the sixth month, respectively. The CG and IG did not present a significant difference with respect to these parameters. Meat consumption and offering dinner on the previous day were significantly higher in the CG than the IG at baseline (Table 3).

Table 3 Dietary intake of the children (<2 years) according to experimental group in the nutritional intervention on complementary feeding practices; Nova Lima, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil, 2015

CG, control group (received standard food and nutrition education in writing); IG, intervention group (received the same information as the CG and face-to-face meetings).

McNemar’s test was used for intragroup comparison; the χ 2 test or Fisher’s exact test for intergroup comparison.

aStatistically significant intergroup difference, P<0·05.

b,cStatistically significant intragroup difference in post-test, P<0·05.

Regarding the parents’ beliefs, attitudes and intentions, the attitude of offering meat from the sixth month was significantly higher in the CG than in the IG (P=0·007; Table 4). The IG’s intention of offering soups or broths to the child was significantly greater than the CG’s intention at baseline (P=0·018; Table 4). The other variables did not differ between the groups at baseline.

Table 4 Intragroup and intergroup differences in parents’ beliefs, attitudes and intentions before and after the nutritional intervention on complementary feeding practices; Nova Lima, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil, 2015

CG, control group (received standard food and nutrition education in writing); IG, intervention group (received the same information as the CG and face-to-face meetings).

aStatistically significant difference pre-test between CG and IG (χ 2 test), P<0·05.

bStatistically significant difference post-test between CG and IG (χ 2 test), P<0·05.

cStatistically significant intragroup difference in IG (McNemar’s test), P<0·05.

† Belief measured with a Likert scale of 3 points (‘I agree’, ‘indifferent’, ‘I do not agree’).

‡ Attitude measured with a 3-point scale (‘very good’, ‘good’, ‘bad’).

§ Intention (‘Next weekend, I will ...’) measured with a 4-point scale (‘definitely’, ‘probably’, ‘probably not’, ‘definitely not’).

In the IG, 3·6 % of the parents attended all the meetings; 7·1 % participated in three meetings; 27·0 % and 35·1 % attended two and one meeting, respectively; and 27·0 % did not attend any meeting (these were excluded from the analyses).

Regarding food consumption, only the IG had a significant increase in meat intake the day before the test (P=0·003) and offering dinner to the infant (P=0·027) after the nutritional intervention (Table 3). This group also consumed large quantities of soft drinks (P=0·007) in the month preceding the final questionnaire, with the values being below those of the CG (P=0·021). The consistency of the foods offered to the infants evolved significantly from ‘mashed’ to ‘like the rest of the family’ after the interval of 8 months between assessments in both groups (P<0·001). There was no significant intergroup difference after the intervention.

After the nutritional intervention, there was a significant increase in the number of parents who believed that children should be given meat from the sixth month in the IG (P=0·008; Table 4). The belief that soups and broths do not nourish the child improved significantly after the intervention in the IG (P<0·001). Similarly, it was observed that the intention of the parents to provide such foods to their children was significantly reduced (P=0·001; Table 4).

The intention of the participants to continue breast-feeding after 6 months (P=0·001) and offer mashed or diced foods to the infants (P=0·004) was significantly lower after the intervention in the IG (Table 4). Comparing the CG and the IG in the final stage showed a greater significant difference among the parents of the IG in the intention to offer vegetables that their infants might not like (P=0·006; Table 4). There was no significant difference in any of the analysed variables regarding beliefs, attitudes and intentions after the intervention in the CG.

Discussion

The present study showed that the nursery professionals who work with infants have some knowledge regarding breast-feeding and complementary feeding; however, this knowledge is insufficient for the appropriate care of infants. After the intervention, the CG and IG evolved favourably, with the greatest learning occurring in the IG. Unlike the professionals, the adherence of the parents in the IG was very low, although there was a significant improvement in some of the parameters assessed. In the CG, no changes were observed in the parents’ beliefs, attitudes and intentions after the intervention.

Regarding knowledge about the introduction of complementary feeding, previous studies have revealed that caregivers have insufficient knowledge of infant feeding and have highlighted the need for training programmes for nursery professionals to assure quality care for the infants in their care( Reference Bento, Esteves and França 21 – Reference Silva, Taddei and Konstantyner 24 ).

The professionals presented prior knowledge of the foods that should not be offered to infants, such as sugar, coffee, tea and canned food. These findings hindered the production of any additional knowledge after the intervention in matters relating to these subjects.

Fewer correct responses were found relating to the type of foods that should be initially offered to the infant and until what age the infant should be breast-fed. It is extremely important for nursery professionals to acquire this knowledge since they are responsible for introducing complementary feeding at the institution and often guide the parents, even when they do have all the required information( Reference Souza, Prudente and Silva 23 ).

A comparison of the control and intervention groups showed that written guidelines alone, without meetings, led to few effective results. Susin et al.( Reference Susin, Giugliani and Kummer 25 ) managed to increase breast-feeding rates with a simple intervention strategy that consisted of a video on breast-feeding, an explanatory booklet and free discussion after the video. Short and simple interventions are easier to plan and routinely execute, considering the number of professionals needed to perform these interventions. Nevertheless, face-to-face intervention can provide more effective results, mainly due to the possibility of having discussions and responding to queries. However, considering the current numbers of technical staff in the municipalities, there are not enough professionals in the National School Feeding Programme (PNAE) for the numerous tasks related to school meals, including FNE( Reference Scarparo, Oliveira and Bittencourt 26 ). It is therefore necessary to increase the number of nutrition professionals in the programme and consequently ensure the appropriate introduction of complementary feeding in local nurseries.

It is important to highlight that the nutritional intervention in the work setting enabled greater adherence, considering that the participation of the professionals was satisfactory, while only a small portion of the parents attended the entire course because they did not have sufficient free time. Low adherence of parents to nutritional intervention programmes has been reported in other studies and was justified by the lack of availability, difficulty in keeping to the schedules of the lectures and lack of interest in actually changing the lifestyle of their children( Reference Jugend 27 ). The scarcity of effective programmes that really help parents improve the nutrition of their children has also been discussed( Reference Nyberg, Sundblom and Norman 28 ). Thus, training in educational activities from graduation must ensure ongoing programmes with effective results.

In relation to the parents, the comparison between groups showed a significant improvement for the IG in relation to changes in consumption, beliefs, attitudes and intentions. The study of Monterrosa et al.( Reference Monterrosa, Frongillo and Cossío 12 ) also found positive results after an intervention with large-scale media, such as radio and leaflets in vaccination campaigns, and suggests the use of simple and viable strategies to support complementary feeding practices. In addition, a qualitative study revealed that, although parents are aware of the WHO recommendations, the influence of colleagues who suggest the early introduction of foods impairs the implementation of these recommendations. Conversely, a trusting relationship with a health-care professional whose practice and advice are consistent with the recommendations was one of the factors that contributed to appropriate complementary feeding( Reference Walsh, Kearney and Dennis 7 ).

With respect to breast-feeding until the sixth month, a prevalence of 18·5 % found in the present study, with the median duration of breast-feeding of 135·0 d (4·5 months) being much lower than that found in Brazilian capital cities: 41·0 % and 341·6 d (11·2 months), respectively( 13 ). International data also present higher breast-feeding rates than those found in the present study, namely 37·0 % of exclusive breast-feeding until the sixth month in low- and middle-income countries and 27·0 % in developed countries( Reference Victora, Bahl and Barros 29 ). This fact can be explained by the profile of the infants in the present study, as the mothers returned to work after the fourth month of maternity leave and started taking formula to the municipal nurseries. The Second Survey of the Prevalence of Breastfeeding in Brazilian State Capitals and the Federal District( 14 ) shows a predominance of exclusive breast-feeding and breast-feeding among women who do not work outside the home or are on extended maternity leave of 6 months. More recent data also corroborate these findings( Reference Silva, Taddei and Konstantyner 24 ). These findings point out the importance of actions to incentivize breast-feeding among mothers who return to work and reveal the need for continuous FNE based on partnerships between the departments of education and health to achieve results that resemble the global average among mothers who work outside the home.

The introduction of complementary foods before the sixth month also showed a value higher than the national frequency (48·3 v. 20·7 % in a national survey). This difference was also expected due to the replacement of breast milk for baby formula at the nurseries, and the consequent start of complementary feeding from the fourth month, as recommended by the Food Guide for Children under Two Years Old ( 15 ).

The limitations of the present were the comparison of non-randomized groups with some differences at baseline, as well as the low adherence of the parents to the nutritional intervention. However, it is worth noting the real health-related context of the research and the absence of significant differences in the outcome variables prior to the intervention. Regarding the adherence of the parents to the intervention, this still represents a huge challenge in FNE and reveals the need to create future strategies that efficiently encourage the participation of parents.

Despite the limitations, the potential of the study should be highlighted. The professionals who cared for the infants learned more about infant nutrition, which can improve the quality of the services they provide. Furthermore, the study shows the importance of intense intervention in the childcare setting to promote healthy supplementary feeding. In addition, the findings may provide education and health managers with the evidence they need to plan nutritional support of the PNAE, with breast-feeding support and the appropriate introduction of complementary feeding.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the current study showed that the nursery professionals and parents of children from 4 to 24 months of age had some knowledge about complementary feeding; however, this knowledge was insufficient to ensure the appropriate introduction of foods to children in this age group. The face-to-face intervention had a significantly greater effect on the evaluated parameters, denoting the importance of its application in infant care services to improve the introduction of complementary feeding.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank the Núcleo de Nutrição da Secretaria de Municipal de Educação de Nova Lima for helping with the data collection. Financial support: This work was supported by the Secretaria de Educação da Prefeitura Municipal de Nova Lima/MG, Brazil and Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG). The funders had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None to declare. Authorship: N.A.C. participated in the project design, bibliographic review, data collection, statistical analysis and article writing. T.M.S. provided technical support for the execution of the project and participated in the review of the article. L.C.S. acted in the coordination of the project, orientation of the students involved, statistical analysis and review of the article. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (CAAE 44107215.3.0000.5149). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.