Postpartum weight retention can contribute to the development of obesity in women(Reference Gunderson and Abrams1, Reference Gore, Brown and West2). Given the breadth of negative health outcomes associated with obesity(Reference Must, Spadano and Coakley3, Reference Calle, Rodriguez and Walker-Thurmond4) and its prevalence in the USA(Reference Ogden, Carroll and Curtin5), it is imperative that risk and protective factors for obesity be identified.

Postpartum weight retention is highly variable, but has been consistently associated with a small number of important risk factors including black race(Reference Parker and Abrams6–Reference Smith, Lewis and Caveny8), pre-pregnancy weight(Reference Gunderson, Abrams and Selvin9) and the amount of weight gained during pregnancy(Reference Viswanathan, Siega-Riz and Moos10, Reference Rooney and Schauberger11). Protective factors are less well studied, but include modifiable behavioural strategies such as healthy diet and physical activity(Reference Amorim, Linne and Lourenco12–Reference Ohlin and Rossner15) and mode of infant feeding.

Studies conducted across various populations have found a significant relationship between the duration of breast-feeding and postpartum weight change, particularly when breast-feeding continued for at least 6 months(Reference Ohlin and Rössner16–Reference Baker, Gamborg and Heitmann20). Other studies report the effect of breast-feeding on postpartum weight loss to be absent(Reference Dugdale and Eaton-Evans21) or minimal and easily confounded(Reference Janney, Zhang and Sowers22–Reference Gigante, Victora and Barros23), leading some to characterize the evidence of a relationship as being mixed or inconclusive(Reference Butte and Hopkinson24–Reference Ip, Chung and Raman26). One reason for this variation in findings may be that the effect of breast-feeding can be attenuated by excessive energy intake(Reference Winkvist and Rasmussen27). It may also be that breast-feeding must be sustained for a minimum period before a significant impact on weight loss can be realized(Reference Ohlin and Rössner16, Reference Dewey, Heinig and Nommsen17).

The objective of the present analyses was to determine the effect of breast-feeding on weight retention at 3 and 6 months postpartum in a large, racially diverse cohort, adjusting for important demographic and weight-related covariates.

Methods

Data

We investigated the relationship between breast-feeding and postpartum weight retention in women who participated in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) in North Carolina. The WIC Programme provides vouchers for food and beverages, education about nutrition and health-care referrals to low-income pregnant women, non-breast-feeding postpartum women (up to 6 months after the birth of an infant), and breast-feeding women (up to the infant’s first birthday), as well as their children up to the age of 5 years. Data including height and weight are collected when women are admitted to the WIC Programme during pregnancy, and at the postpartum recertification visit, when the mother renews her participation in WIC after giving birth.

North Carolina’s Pregnancy Nutrition Surveillance System (NC PNSS) is compiled by linking data from the WIC Programme with birth certificates and fetal death certificates. The data used in the present study were collected through the NC PNSS, and include variables from the WIC prenatal and postpartum clinic visits and from the birth certificate (including delivery date and mother’s demographic data). Data from all pregnancies in the NC PNSS from 1996 to 2004, which had been de-identified with the exception of a coded WIC participant identification number, were obtained through a data use agreement for these analyses. This agreement and the study protocol were approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board.

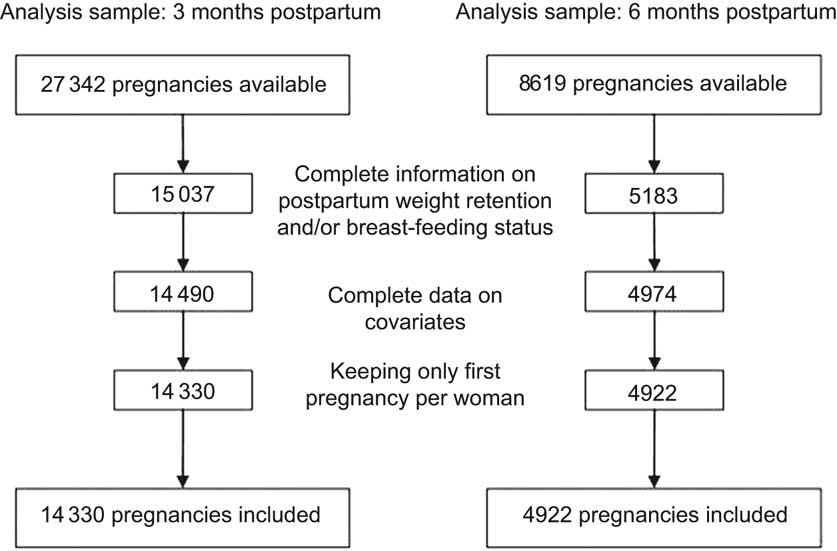

The paper presents a retrospective follow-up study of postpartum weight retention in women recertifying in the WIC Programme at 3 (60–90 d) and 6 (150–180 d) months postpartum. We removed records with missing data and, since there were some women with multiple pregnancies in the data set, selected only one pregnancy per woman to use in the analysis. As shown in Fig. 1, these steps resulted in final sample sizes of 14 330 and 4922 women at 3 and 6 months postpartum, respectively.

Fig. 1 Samples used in statistical analysis

Measures

Postpartum weight retention

Postpartum weight (in pounds) for each woman was measured at the WIC postpartum recertification visit. Self-reported pre-pregnancy weight (in pounds) was collected at the WIC prenatal visit. The outcome for these analyses, postpartum weight retention, was derived by subtracting the self-reported pre-pregnancy weight from the measured postpartum weight. Acceptable ranges for weight (80–600 lbs) and postpartum weight retention (−75 to 100 lbs) were established based on distributions within the study samples. All weight-related variables were converted to kilograms for final analyses.

Breast-feeding

Three separate questions assessed breast-feeding status at the time of the postpartum visit: current breast-feeding (yes/no), when breast-feeding was discontinued (age of infant in weeks), and when formula was first introduced (age of infant in weeks). To be categorized in the ‘full breast-feeding’ group, women had to answer that they were currently breast-feeding, had never discontinued breast-feeding, and had never introduced formula. Women categorized as ‘mixed feeding’ (combining breast-feeding with formula-feeding) responded that they were currently breast-feeding, had not discontinued breast-feeding, but had introduced formula. To be categorized as ‘formula-feeding’, women had to report that they were not currently breast-feeding, had discontinued breast-feeding before the time of the visit and had introduced formula before the time of the visit.

Covariate measures

We adjusted for seven covariates related to breast-feeding or weight retention in assessing the association between the two. These included the woman’s age (range: 12–49 years), race, ethnicity (Hispanic; yes/no), education (range: 0–17 years), parity (range: 1–8), gestational weight gain and pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2). Height was needed to derive the pre-pregnancy BMI; if the measured height at the postpartum recertification visit was missing or out of range (48–72 in), a prenatal measure was used (if available and in range). Given its high correlation (0·944) with pre-pregnancy weight, pre-pregnancy BMI also served as the baseline control value of the outcome in the multivariable model.

Statistical analysis

The general linear model was used to test the association of weight retention with breast-feeding at 3 and 6 months, controlling for the covariates listed above. Breast-feeding was tested with two separate contrasts, i.e. full breast-feeding v. formula only; and mixed feeding v. formula only. Race was categorized as black v. non-black, after determining the goodness-of-fit of this dichotomy. All categorical variables were modelled with reference cell coding. Continuous variables were modelled as linear unless their quadratic terms were significant; thus, P values for continuous variables may have either 1 or 2 df (cubic terms were also tested, but none was statistically significant). All covariates were included in the multivariate model, regardless of P value, as recommended by Harrell(Reference Harrell28). Postpartum weight retention was well approximated by normal distribution.

Means with their standard errors on weight retention are presented according to breast-feeding status and levels of the covariates, where, for the purpose of presentation, continuous covariates are categorized at clinically meaningful cutpoints. Pre-pregnancy BMI was categorized according to the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute guidelines(29), and gestational weight gain according to the recommendations of the Institute of Medicine(30). Covariate-adjusted effects are presented as regression coefficients from the multivariate regression model. Regression coefficients for dichotomous predictors are equal to the covariate-adjusted mean difference in weight retention between the two categories. Regression coefficients for continuous predictors include a linear term and possibly a quadratic term. The quadratic terms, while significant, forced only very slight curvatures away from linearity. Therefore, all linear terms can be thought of as being equal to (or a very good approximation of) the change in mean weight retention for a one-unit increase in the covariate. All statistical tests used a two-sided α of 0·01. Statistical analysis was performed using the SAS statistical software package version 8·2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

When comparing women included in the analysis to those excluded, the women excluded at 3 months were more likely to be older, white, Hispanic and more educated; they had fewer children and gained less weight during pregnancy. At 6 months, only white women and those with lower gestational weight gain were more likely to be excluded. In general, these differences were small and assumed to be clinically unimportant with the exception of race; at both time points, black women were more likely to have complete data than whites and other races.

Characteristics of the WIC participants who were included in the 3 and 6 months postpartum analysis samples are presented in Table 1. In the 3-month sample, 7 % of women were fully breast-feeding and 16 % were mixed feeding. In the 6-month sample, 25 % were fully breast-feeding, whereas 47 % were mixed feeding. The rates of breast-feeding at this time point appear higher because women who are formula-feeding may receive WIC benefits only up to 6 months postpartum. As this deadline approaches, fewer formula-feeding women are recertifying and the proportion of breast-feeders is high. As a result, the 6-month group was slightly older, and had a greater proportion of whites and Hispanics. They were more likely to have three or more older children in addition to the current newborn, and also more likely to have some college education. In the 3-month sample, 16 % of births were preterm and 2 % were multiple gestation; in the 6-month sample, 8 % of births were preterm and 1 % was multiple gestation (data not shown). Mean postpartum weight retention was 5·3 (sd 6·9) kg in the 3-month postpartum sample and 5·6 (sd 7·0) kg in the 6-month postpartum sample (data not shown).

Table 1 Description of WIC samples from 1996 to 2004

WIC, The North Carolina Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children; IOM, Institute of Medicine.

*Data are presented as mean and sd.

Means on weight retention according to levels of the covariates, including breast-feeding, are presented in Table 2. Weight retention did not differ by breast-feeding status at 3 months. At 6 months, mean weight retention in mixed feeders was 1·6 kg lower than in formula-feeders, and 1·8 kg lower in full breast-feeders. At both time points, mothers who were older, more educated and had more children retained less weight. Hispanic women retained less weight than non-Hispanics, while results differed for black women at 3 and 6 months postpartum. Women with greater gestational weight gain retained more weight at both time points, while increased pre-pregnancy BMI was associated with reduced postpartum weight retention.

Table 2 Mean weight retention according to the levels of the predictor variables at 3 and 6 months postpartum

IOM, Institute of Medicine.

The effect of breast-feeding status on weight retention at each time point, controlling for covariates, is presented in Table 3. At 3 months postpartum, there was no association between breast-feeding and weight retention. At 6 months postpartum, as compared to formula-feeders, mean weight retention was 0·84 kg lower among mixed feeders (95 % CI 0·39, 1·29; P = 0·0002) and 1·38 kg lower among full breast-feeders (95 % CI 0·89, 1·87; P < 0·0001). In addition, at 6 months postpartum, women with more education retained less weight (0·14 kg/year of education; P = 0·0002) and black women retained 1·33 kg more than women of other races (P < 0·0001). Weight gain during pregnancy had the largest effect of any variable in the models, with women retaining about half of every kilogram gained during pregnancy at both time points (P < 0·0001). Increased pre-pregnancy BMI was negatively correlated with postpartum weight retention.

Table 3 Predictors of weight retention at 3 and 6 months postpartum; multivariable linear regression

*Reference category: formula-feeding.

†Reference category: all other races.

‡Reference category: non-Hispanic.

§Variables with a corresponding quadratic term (2 df test) noted in parentheses as (2).

Discussion

In this large, racially diverse sample of low-income women, breast-feeding status had no effect on weight retention at 3 months postpartum but had a significant effect at 6 months postpartum. At this later time point, full breast-feeding conferred a greater benefit than did mixed feeding, indicating that the amount of breast-feeding is inversely correlated with weight retention in the postpartum period. Nevertheless, both mixed and full breast-feeding resulted in greater postpartum weight loss when compared to formula-feeding.

Our differing results at 3 and 6 months postpartum are congruent with previous findings(Reference Dewey31). In a study of 1423 Swedish women over the first postpartum year, Ohlin and Rossner(Reference Ohlin and Rössner16) found that the impact of breast-feeding was greatest between 2·5 and 6 months after delivery. Dewey et al.(Reference Dewey, Heinig and Nommsen17) followed forty-six breast-feeding and thirty-nine formula-feeding women for 2 years, and similarly found no difference in weight loss between the groups from 1 to 3 months, but a significant difference from 3 to 6 months postpartum. Although some other studies have presented data on the effect of weight loss at more than one time point up to 18 months postpartum(Reference Kac, Benício and Velásquez-Meléndez19–Reference Baker, Gamborg and Heitmann20, Reference Janney, Zhang and Sowers22), few quantify the impact of breast-feeding duration before 6 months after delivery. Our results are consistent with those of Ohlin and Rossner(Reference Ohlin and Rössner16) and of Dewey et al.(Reference Dewey, Heinig and Nommsen17), but in a much larger and racially diverse cohort.

Further, despite the sizeable effects of such measures as race, education, pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain, the effect of breast-feeding at 6 months postpartum remained after controlling for these variables. Together with the studies discussed above, as well as the recent report by Baker et al.(Reference Baker, Gamborg and Heitmann20) (which showed a significant effect of breast-feeding on weight retention at 6 months postpartum in a large cohort of Danish women), our results support the hypothesis that there is an independent effect of breast-feeding on postpartum weight loss if breast-feeding is continued for at least 6 months.

The fact that we observed an association between breast-feeding and weight loss at 6 months and not at 3 months postpartum may indicate that a certain breast-feeding duration is necessary for the maximal effect to be observed. The average energy cost of lactation is 2092 kJ (500 kcal)/d; therefore, the greater energy deficit experienced with 6 v. 3 months of lactation likely contributed to the different results at each time point. In addition, Lof and Forsum(Reference Lof and Forsum32) showed that expansion of plasma volume during pregnancy can persist during at least the first month postpartum. They measured body water in healthy women before, during and after pregnancy and reported an average of 2 kg of fluid remaining at 2 weeks postpartum. It is plausible that such physiological after-effects of pregnancy may mask differences in weight loss between lactating and formula-feeding women in the early postpartum period.

The strengths of the present study include a large, racially diverse sample, and the availability of important control measures such as race, pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain. Its limitations include the fact that the measures at 3 and 6 months were not collected serially from the same individuals, but from separate groups of women recertifying at each time point, which must be taken into consideration when interpreting the results reported and when making comparisons with other studies. The women in the present study were all low-income participants in the WIC Programme; while this limits generalizability to the general population, it does reasonably represent low-income women in the Southern USA, a group that is at higher risk for obesity and that has lower rates of breast-feeding. Lower proportions of formula-feeders were likely to recertify as late as 6 months postpartum, and case loss due to missing data was also a limitation. Finally, the relationship between pre-pregnancy BMI and postpartum weight loss may have differed at later time points, had they been available. Baker et al.(Reference Baker, Gamborg and Heitmann20) found in their sample, as in the current study, that pre-pregnancy BMI was negatively associated with weight retention at 6 months postpartum. However, Gunderson et al.(Reference Gunderson, Abrams and Selvin9) noted that early postpartum weight loss in their sample did not vary by pre-pregnancy BMI, but that late postpartum weight change (i.e. a median of 2 years after delivery) did.

The positive health effects of breast-feeding for the newborn have been well established(33). Breast-feeding can also be beneficial to the mother’s health, including reduced risks of type 2 diabetes, ovarian cancer and breast cancer(Reference Ip, Chung and Raman26). These benefits have made the promotion of breast-feeding a Healthy People 2010(34) priority as well as a major component of the WIC educational programme(35). Our results suggest that breast-feeding can also effect modest reductions in postpartum weight retention, adding to its overall benefits to the mother and child.

Earlier reports indicate a lower rate of breast-feeding among WIC participants than in the general population(Reference Ryan and Zhou36–Reference McCann, Baydar and Williams38). Encouraging breast-feeding is especially important in low-income women, who are disproportionately affected by obesity and related health problems that may be positively impacted by breast-feeding. Studies of WIC groups suggest that participants are aware of the health benefits of breast-feeding for their infants, and that structural barriers such as return to work are less of a problem than attitudinal barriers, including embarrassment about public feeding, the perception of breast-feeding as limiting or inconvenient, and fears of inadequate supply(Reference McCann, Baydar and Williams38). Such attitudes are amenable to intervention and education, and WIC Programmes designed to educate participants and provide peer-counselling support services have shown that they can positively impact breast-feeding in this population(Reference Ahluwalia, Tessaro and Grummer-Strawn39–Reference Gross, Resnik and Cross-Barnet41).

Further, implementation of a new WIC food package design, effective from 1 October 2009, is an important step forward in breast-feeding promotion efforts in this population. This change is the result of an Institute of Medicine review of the WIC Programme food packages and addresses concerns that formula supplementation available through WIC may have the unintended effect of de-incentivizing breast-feeding in this population(42). The new food packages align with the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans and infant feeding practice guidelines of the American Academy of Pediatrics, and are designed to better promote and support the establishment of successful long-term breast-feeding. Such efforts are widely supported and have the potential to impact perceptions about breast-feeding and formula supplementation among WIC participants(Reference Holmes, Chin and Kaczorowski43). Given that up to half of all infants in the USA participate in WIC(Reference Ryan and Zhou36), encouraging breast-feeding in this population could benefit the overall health of a substantial proportion of American women and children.

Conclusion

In this large, racially diverse sample of low-income women participating in the WIC Programme, breast-feeding was associated with reduced weight retention at 6 months postpartum, controlling for important demographic and weight-related covariates.

Acknowledgements

The present study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. K.M.K. conducted the analyses and wrote the manuscript. C.A.L. conceived the study and acquired the data. T.Ø. and C.A.L. participated in designing the study and assisted in analysing the data and editing the manuscript. B.L.P. assisted in statistical design, analysis and reporting. N.C. provided consultation on data and reviewed the analysis and manuscript for completeness and accuracy. The authors thank Alice Lenihan, RD, MPH, LDN, Branch Head of Nutrition Services Branch, NC DHHS, for facilitating access to the data used in the present study report. They also thank Dr Sara Benjamin for her helpful suggestions.