Australia has been accepting migrants since it was colonised over 200 years ago. In more recent history, significant waves of migration have occurred after major world conflicts, and Australia continues to be a settlement destination for both migrants and refugees. It is now one of the most culturally diverse populations in the world with more than one-quarter (26 %) of Australians born overseas, and 19 % born in countries where English is not the first language(1). There is however, a disproportionate burden of disease among ethnic groups in Australia with considerable variability depending on the country of origin(Reference Anikeeva, Bi and Hiller2). Although there is, for some voluntary migrants, a ‘healthy migrant’ effect on arrival, it would appear that the longer the duration of residence, the higher the prevalence of risk factors that lead to morbidity and mortality from chronic conditions(Reference Koya and Egede3–Reference Renzaho5).

While it is increasingly recognised that migrants and refugees in Australia are experiencing a higher burden of disease, in particular related to obesity, heart disease and type 2 diabetes(Reference Menigoz, Nathan and Turrell6–Reference Guo, Lucas and Joshy8), little is known about how suboptimal diet and physical activity contribute to this burden. A large body of literature in countries with similar migration histories to Australia, such as Canada and the USA, indicates that diets and physical activity potentially worsen with length of time spent in the host country. That is, a majority of migrants and refugees move from healthier traditional diets to less healthy, more industrialised diets, and from labour-intensive activities to being more sedentary(Reference Sanou, O’Reilly and Ngnie-Teta9,Reference Alidu and Grunfeld10) . This acculturation of eating and physical activity behaviours was thought to contribute to the worsening health of migrants. In addition to acculturation, socioeconomic status, which is a known social determinant to poor health and higher rates of non-communicable diseases (NCD)(Reference Marmot and Bell11), may play a role in this trend. Many (but not all) migrants and refugees experience periods of low income exacerbated by low employment and lack of recognition of qualifications(Reference Correa-Velez, Barnett and Gifford12).

The impact of migration on diet and physical activity is perhaps more complex in the current context. There is an increased international influence of multinational companies and the distribution and consumption of ultra-processed foods especially in low-middle-income countries(Reference Baker and Friel13,Reference Ford, Patel and Narayan14) . For example, there are indications of dietary pattern changes in China(Reference Du, Lu and Zhai15), Malaysia(Reference Lipoeto, Geok Lin and Angeles-Agdeppa16), India(Reference Law, Fraser and Piracha17), Africa(Reference Holmes, Dalal and Sewram18) and Vietnam(Reference Nguyen and Hoang19), all major source countries of migrants to Australia. This means that access to these more industrialised foods is not limited to the host country, and transitioning from a more ‘traditional’ to a more ‘industrial’ or ‘Western’ diet is less clear-cut. Increasing urbanisation in many low- and middle-income countries has reduced opportunities for physical activity; therefore, increasingly, many migrants/refugees may be arriving in Australia with low baseline activity levels(Reference Popkin, Adair and Ng20).

There is limited research on changes to dietary and physical activity patterns of culturally and linguistically diverse communities in Australia. Early work indicated retention of traditional diets by post-World War II migrants from Greece(Reference Kouris-Blazos, Wahlqvist and Trichopoulou21), but both retention and negative changes to the diets of migrants from China in the 1990s(Reference Hsu-Hage and Wahlqvist22). Dietary patterns of South Asian women living in Brisbane appeared to be related to their acculturation (including not only length of time in Australia but also interactions with people outside their communities)(Reference Gallegos and Nasim23). Dietary transitions have also been noted in refugees and migrants from Somalia(Reference Burns24), South Sudan(Reference Renzaho and Burns25) and Ghana(Reference Saleh, Amanatidis and Samman26), and Samoa(Reference Perkins, Ware and Felise Tautalasoo27). Regarding physical activity, a range of barriers are identified that limit physical activity and sports participation by the members of culturally and linguistically diverse communities. Some examples include language difficulties, job characteristics, access to information, geographic isolation and social support(Reference O’Driscoll, Banting and Borkoles28–Reference Caperchione, Kolt and Mummery30).

These studies have tended to focus on a particular cultural group, and there are limited studies exploring the differences in diet and physical activity behaviours of migrants/refugees from different cultural backgrounds in Australia(Reference Astell-Burt, Feng and Croteau31). The aim of this study was to, therefore, investigate differences in eating and physical activity behaviours among ethnic groups in Queensland, Australia, and whether these behaviours vary due to the duration of residency in Australia.

Methods

Study design and population

This study used baseline data from the Living Well Multicultural–Lifestyle Modification Program (LWM-LMP) delivered by the Ethnic Communities Council of Queensland (ECCQ). The programme was developed using best practice principles tailored specifically for individual culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities and delivered by trained multicultural health workers (MHW). The purpose was to improve community awareness regarding changing behaviours that increase the risk of NCD. The programme was delivered throughout Queensland with a majority of programmes delivered in the primary metropolitan area (Brisbane).

CALD communities targeted in this programme were Afghani, Arabic-speaking, Burmese, Pacific and South Sea Islander, Somali, Sri Lankan, Sudanese and Vietnamese. A variety of strategies were used to recruit participants, including via newsletters, advertisements in community-specific newspapers and radio channels, ECCQ and community associations’ websites, referrals and word-of-mouth. People who were living in these CALD communities and aged ≥18 years were eligible to participate. All sessions were conducted in the language of choice of the CALD community, and so English ability was not a criterion for inclusion. Written consent was obtained from all participants.

Measures

Independent variables

Ethnicity was self-reported by participants. Although there were nine different ethnicities, they were categorised into five main groups based on geographic location: Burmese/Vietnamese (South East Asia), Sri Lankan/Bhutanese (South Asia), Afghani/Arabic-speaking (Middle East), Somali/Sudanese (Africa) and Pacific Islander. These emerging or established communities were targeted as they had known chronic disease risk.

The duration of residency in Australia, as a representation of acculturation, was self-reported at the beginning of the study. A cut-point of 5 years was used as a previous study showed that cardiometabolic risks of migrants increased within 5 years of settling in Australia(Reference Gallegos, Do and To32). Participants were grouped into a duration of ‘≤5 years’ or ‘>5 years’. Another cut-point of 1 year was also used in the analysis to determine if any changes in behaviour had occurred.

Dependent variables

Eating behaviours

Questions from the Australian National Health Survey(33) and the Queensland Self-reported Health Status Survey, with minor modifications to include foods relevant to cultural groups, were used to assess participants’ eating behaviours. The stem of the questions remained the same to retain validity, and minor modifications were made in conjunction with the MHW and included, for example, hot chips such as fried taro, sweet potato and cassava. The questions asked about frequencies of having fruit, vegetables, processed meat, fast food, hot chips, salty snacks, sweet snacks and sweetened beverages. Types of milk were also asked. A score of 1 was assigned for each of the items if the frequencies were ≥2 pieces of fruit per day, ≥5 servings of vegetables per day, <1 time per week for processed meat, meals from fast food/takeaway outlets, hot chips/fries, salty snacks, sweet snacks and sweetened beverages; and also if low-fat milk was usually consumed. Otherwise, a score of 0 was assigned. These scores were summed to create an eating behaviour score for each participant (range 0–9, where 0 is a low score). A majority of validated tools used in the Australian context have not been validated in specific CALD communities. See online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1a for changes made.

Physical activity

Physical activity was assessed using three questions based on the Active Australia survey(34), asking about the time spent on walking, moderate and vigorous physical activity in the last week. The total activity time was calculated by summing the above times (with vigorous physical activity time doubled). Participants were then categorised into two groups: meeting the Australian physical activity guidelines when the total activity time is at least 150 min/week, or otherwise not meeting the physical activity guideline(34). See online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1b for changes made.

Covariates

Participants self-reported demographic characteristics, including age, gender, level of education, employment status and household type. Gender was categorised as ‘female’ or ‘male’. Levels of education were ‘primary school’, ‘high school’, ‘certificate/diploma’ or ‘bachelor/postgraduate degree’. Employment status included ‘paid work’, ‘work without pay’, ‘retired/unemployed’ or ‘student’. Types of household were classified into ‘living alone with no children’, ‘single parent living with one or more children’, ‘single living with friends or relatives’, ‘couple living with no children’ or ‘couple living with children’. Weight and height were measured by MHW. BMI was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m)2. Weight, height and BMI were used as continuous variables.

Data analysis

SAS software, v9.4, was used to analyse the data. Frequencies and percentages were generated for categorical variables; means and standard deviations were generated for continuous variables. Due to low numbers in some of the cultural groups, it was decided to combine groups based on geographic location and body composition, for example, Bhutanese with Vietnamese, Somali with Sudanese. These descriptive statistics were presented for each ethnic group. Linear regressions were performed to test associations between eating behaviour score with ethnicity and duration of residency in Australia, whereas logistic regressions were run to test the association between meeting the physical activity guideline with ethnicity and duration of residency in Australia. In addition to bivariate models, likelihood ratio tests and information criteria were used to select variables in multivariable analyses. For associations between eating score and meeting the physical activity guideline with ethnicity, results were adjusted for age, gender, education level, employment status, household types and time in Australia. For associations between eating score and meeting the physical activity guideline with duration of residency in Australia, results were adjusted for ethnicity, age, gender and education level. Interaction between sex and ethnic group was not significant and, therefore, was not included in the models. Participants with missing data for covariates were excluded in multivariable analysis. Tukey–Kramer adjustment was applied for multiple comparisons between ethnic groups. Burmese/Vietnamese participants were used as the reference group. Differences/OR and 95 % CI were reported. All P values were two-tailed and, if less than 0·.05, were considered statistically significant.

Results

There were 700 participants; 16 % were Somali/Sudanese, 18 % Burmese/Vietnamese, 20 % Sri Lankan/Bhutanese and 23 % each for Afghani/Arabic-speaking and Pacific Islander. Characteristics of these groups are presented in Table 1. Across the ethnic groups, more females participated in the programme, ranging from 54 % (Sri Lankan/Bhutanese) to 81 % (Afghani/Arabic-speaking). Levels of education, employment status and household types were different among the groups. A majority of Burmese/Vietnamese, Somali/Sudanese and Pacific Islanders had an education level of high school or less, whereas a majority of Sri Lankan/Bhutanese and Afghani/Arabic-speaking participants had an education level of above high school. The proportion of participants with paid work was highest for Pacific Islanders (58·6 %) and lowest for Afghani/Arabic-speaking participants (12·4 %). A majority of participants were couples living in households with or without children. The proportions of participants living alone ranged from 2·5 % (Afghani/Arabic-speaking) to 8·9 % (Burmese/Vietnamese). Somali/Sudanese participants were the youngest with an average age of 36 years; and Burmese/Vietnamese participants were the oldest with an average age of 55 years. Burmese/Vietnamese participants had the lowest average BMI. A majority of Burmese/Vietnamese and Pacific Islanders stayed in Australia for over 10 years, whereas a majority of other groups stayed for <5 years.

Table 1 Sample characteristics across ethnic groups

Eating and physical activity behaviours for each ethnic group are presented in Table 2. More than two-thirds of Burmese/Vietnamese met the recommendation for fruit serves (≥2 servings of fruit per day), whereas only one-third of Somali/Sudanese did. Most of the participants across all ethnicities (>92 %) were not consuming the recommended vegetable serves. Low-fat milk consumption ranged between 38 % among Sri Lankan/Bhutanese to 15 % for Somali/Sudanese participants. Somali/Sudanese and Pacific Islander participants regularly consumed processed meats, with 39 % and 26 % consuming these meats at least three times per week. A majority of other groups consumed processed meats less than once per week. More than half of Pacific Islander participants consumed fast food and hot chips at least once per week. A majority of Afghani/Arabic-speaking participants also had hot chips, salty and sweet snacks at least once per week. More than half of Somali/Sudanese participants consumed sugar-sweetened beverages more than once per week. Average eating behaviour scores ranged from 3·4 for Afghani/Arabic-speaking to 5·4 for Burmese/Vietnamese participants. In addition, a majority of all five cultural groups did not meet the physical activity guideline of engaging in at least 150 min of moderate–vigorous physical activity weekly, ranging from 56·0 % (Somali/Sudanese) to 66·5 % (Afghani/Arabic-speaking).

Table 2 Dietary and physical activity (PA) behaviours across ethnic groups

Associations between eating and physical activity behaviours and ethnicity are presented in Table 3, with model 1 showing bivariate associations and model 2 showing multivariable associations. In the bivariate analysis, on average, Afghani/Arabic-speaking, Somali/Sudanese and Pacific Islanders had eating behaviour scores of 2·1, 1·5 and 1·5 points lower than for Burmese/Vietnamese (P < 0·001). After controlling for age, gender, education levels, employment, household types and time in Australia, the differences were 1·2 points lower (P < 0·01) for Afghani/Arabic-speaking, and 1·1 points lower (P < 0·001) for Pacific Islanders compared with Burmese/Vietnamese. The difference was not significant between Sri Lankan/Bhutanese and Somali/Sudanese with Burmese/Vietnamese. Also, there were no significant differences in meeting the physical activity guidelines across the ethnic groups.

Table 3 Differences in eating behaviour scores and OR for meeting the physical activity (PA) guideline (95 % CI)

* P < 0·01, ** P < 0·001.

† Differences in eating behaviour scores between other groups and the Burmese/Vietnamese group are reported.

‡ ‘Not meeting the physical activity (PA) guideline’ is the reference. OR for each group compared with the Burmese/Vietnamese group are reported.

§ Crude differences are reported.

‖ Crude OR are reported.

¶ Differences and OR adjusted for age, gender, education levels, employment, household types and time in Australia are reported.

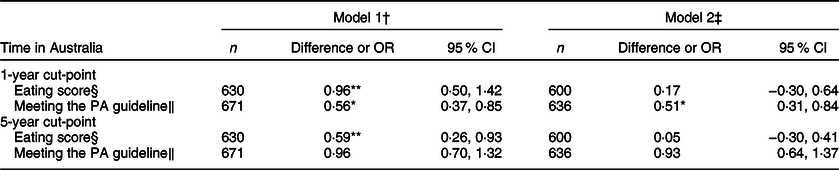

Differences for eating and physical activity behaviours between long-stay and short-stay groups are presented in Table 4. On average, those who had spent <1 year in Australia had eating scores that were 0·96 point lower compared with those staying at least 1 year (P < 0·01). A similar result was found for the cut-point of 5 years although the difference was smaller, that is, those staying <5 years had eating scores that were 0·59 point lower than those staying ≥5 years (P < 0·01). However, for both cut-points, the associations were not significant after adjusting for ethnicity, age, gender and education level. Regarding physical activity, those staying for <1 year were more likely to meet the physical activity guideline than those staying longer (P < 0·05), even after controlling for demographic characteristics. However, with a cut-point of 5 years, the association was not significant.

Table 4 Differences or OR (95 % CI) for eating and physical activity (PA) behaviours between long-stay and short-stay groups

* P < 0·01, ** P < 0·001.

† Model 1 provides crude differences or OR.

‡ Model 2 provides differences or OR adjusted for ethnicity, age, gender and education level.

§ Differences in eating score between long-stay v. short-stay groups are reported.

‖ ‘Not meeting physical activity (PA) guideline’ is the reference. OR are reported for long-stay v. short-stay groups.

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the dietary and physical activity behaviours of and variations between multiple ethnic groups living in Queensland. The findings indicate that all ethnic groups had low consumption of vegetables and relatively high consumption of energy-dense foods. The proportion of communities meeting the physical activity guideline was also low for all groups. In addition, Burmese/Vietnamese and Sri Lankan/Bhutanese were found to have healthier eating behaviours than other groups, although meeting the physical activity guideline was not different across the groups. Physical activity appeared to decline after living in Australia for just 1 year, but changes in dietary behaviours were unclear. With the consumption of vegetables being universally low and the consumption of energy-dense nutrient-poor foods being high, there is no clear pattern of food habits changing positively or negatively after migration. This is contrary to the ‘healthy migrant’ effect experienced by some migrant groups from low- and middle-income countries and indicates that transitioning dietary and physical activity patterns are perhaps more complex given the globalisation of food supply(Reference Baker and Friel13,Reference Monteiro, Moubarac and Cannon35) . It also appears that social determinants, demographics and culture could play a more influential role in determining diet and physical activity behaviours than the length of time spent in a country.

The consumption of inadequate serves of fruit and vegetables is a known contributor to the burden of disease, particularly related to increased rates of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, cancer and obesity, as well as premature all-cause mortality(Reference Aune, Giovannucci and Boffetta36). Compared with all Queenslanders, more members of these ethnic groups were meeting the dietary guidelines for fruit (about one-half (52 %) compared with 25 % of Queenslanders) and vegetable consumption (4·6 % compared with 3·8 %)(37). The proportions among these ethnic groups were, however, comparable to the most recent Australian data that indicate about half (51·3 %) are meeting fruit consumption guidelines. However, with the exception of Pacific Islanders, all ethnic groups had lower proportions of meeting the dietary guidelines for vegetables, compared with the Australian population (7·5 %)(38). Compared with available data from the countries of origin, there is evidence of universally low fruit and vegetable consumption(Reference Miller, Yusuf and Chow39). In Sudan, in 2007, the estimated mean intake of vegetables was 112 g per person per day or 1·4 serves(40), indicating that vegetable consumption may be universally low although the determinants of vegetable intake may differ (e.g. availability rather than taste).

Comparisons between this data and that available nationally are difficult due to the different methodologies used (i.e., short questions v. a 24-h recall). However, it would appear that these ethnic groups were more likely than the Australian population to consume snack foods (33 % compared with 11·7 %) and processed meats more than once a week (45 % compared with 24 %)(41). They were, however, less likely to consume sweet snacks and confectionary (33 % compared with 43 %). Sweetened beverage consumption appeared to be similar, with about half (49·8 %) indicating they never or rarely consumed these (data not presented) compared with 52 % of Australians indicating they did not consume sweetened beverages in 2017(38). Of note were the higher levels of consumption of processed meat (four or more times a week) among the Somali/Sudanese (40 %) and Pacific Islander participants (26 %), and the consumption of snacks by the Afghani/Arabic-speaking group, with one in five and one in three, respectively, consuming savoury and sweet snacks four or more times a week.

Data from a sample of Samoans living in Brisbane correspond with these results, eating fewer vegetables and more fast food compared with a comparable low-income population(Reference Perkins, Ware and Felise Tautalasoo27). While a study of Sub-Saharan African households in Melbourne indicated that about one-third consumed fast food/takeaway at least once a week(Reference Renzaho and Burns25), many of the foods consumed in higher quantities could be considered culture-specific. For example, a higher consumption of sweet snacks and confectionary was found in Somali communities and of processed meats in the Pacific Islands(Reference Reeve, Naseri and Martyn42). There is, however, little data available on what ethnic groups are consuming in Australia, the determinants of consumption and how this impacts health. What is clear is that the consumption of nutrient-poor, energy-dense foods is high and that, given the success of this programme, specific culturally tailored approaches appear to be warranted.

Across all the groups, the level of physical activity was similar although only one-third of the participants were meeting the physical activity guideline. This is lower compared with the general Australian population that had about half (52·6 %) meeting the physical activity guideline(Reference Bennie, Pedisic and van Uffelen43). A possible explanation may be that migrants were living in less advantaged neighbourhoods that potentially discourage engagement in outdoor activities. Lower socioeconomic status may also contribute to lower physical activity levels among the migrants as they may spend much of their days working multiple jobs with little time available for physical activity(Reference Datta44). It is also possible that their level of physical activity was already low before moving to Australia and had not improved since their arrival(Reference Popkin, Adair and Ng20). Culturally adapted interventions may be necessary to help migrants reach the physical activity level of the general population.

Two recent reviews investigating acculturation, obesity and health behaviours identified the positive association between acculturation and high BMI(Reference Alidu and Grunfeld10,Reference Delavari, Sønderlund and Swinburn45) . The review by Alidu and Grunfeld concluded that acculturation could have either beneficial or detrimental impacts on healthy behaviours and that interventions should target migrants early in the settlement process to promote the retention of original healthy behaviours(Reference Alidu and Grunfeld10). This research indicates a higher level of complexity regarding diet and physical activity patterns. The healthy migrant effect states that, with time, diets and physical activity worsen due to an exposure to more industrialised eating patterns and sedentary practices in the host countries. However, some of these migrants have come from countries experiencing nutrition transition and so may already be exposed to more industrialised eating patterns and increased urbanisation(Reference Parry46,47) . These practices may be retained in Australia due to relative availability and lower cost of some foods and individualised transport options.

This study has a number of limitations. First, participants were recruited to an NCD prevention and management programme and may not necessarily be representative of the entire community. In general, participants from ethnic communities, in particular those who have newly arrived, are also difficult to access. However, using MHW to collect data in the community language may result in a more diverse sample compared with other studies that were only conducted in English and, thus, may be more representative of those with higher acculturation levels and English language ability or proficiency. Second, although short questions that had been validated within Australia and adapted to include culturally representative foods were used, they have not been validated for use within individual CALD communities. In addition, they only provided self-reported and subjective evaluation of dietary behaviours. Using other dietary methodologies, such as multipass 24-h recalls and/or culturally specific FFQ, may have provided more comprehensive information. However, in this context, within the resource and time limitations as part of a pragmatic evaluation, the short questions were the best option. Third, the use of our eating behaviour score has not been validated in these populations. Although physical activity data were collected using a version of the validated Active Australia questionnaire, changes to the questions have not been validated. However, the Active Australia survey has also not been validated in different ethnic communities within Australia. Consequently, the calculation of physical activity needs to be interpreted with caution. The main use of the survey was to report on changes made to physical activity across the duration of the programme (not reported here). The use of self-reported questionnaires is also subject to recall bias. Acculturation was only assessed using length of time in Australia rather than more nuanced tools that take into consideration social networks and language for day-to-day interactions. Some ethnic groups were combined to improve statistical strength; this may have masked specific cultural variations. Finally, the study is cross-sectional and is not able to demonstrate changes in behaviours over time.

Conclusion

Dietary and physical activity habits for groups of migrants/refugees living in Queensland are potentially suboptimal and contribute to the burden of NCD and premature death. Eating behaviours were significantly different among the ethnic groups in Queensland with Burmese/Vietnamese and Sri Lankan/Bhutanese having the healthiest diets. Primary prevention campaigns related to diet (Australian Guide to Healthy Eating) and physical activity (Make Your Move–Sit Less–Be Active for Life) in Australia are only available in English and do not take into consideration the potential diversity of practices. It appears that dietary practices may not necessarily worsen but that physical activity may over time. Culturally tailored approaches are needed to improve accessibility to information that will increase the consumption of vegetables; reduce the consumption of energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods; and increase physical activity.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank CALD community members for informing this programme and providing feedback and participation. We would also like to acknowledge Nera Komaric for her work on developing the original modules. Furthermore, we acknowledge the MHW from the Ethnic Communities Council of Queensland, Chronic Disease Program for their contribution, knowledge, hard work, dedication and passion to support CALD communities. Financial support: The Multicultural Healthy Lifestyle Program was funded by the Queensland Government and supported by a state-wide reference group with representatives of key stakeholders from government, non-government and members from CALD communities. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: All authors significantly contributed to the manuscript. D.G., H.D., B.V., J.G., H.A. designed the study. D.G. and Q.G.T. drafted the manuscript. Q.G.T. and B.V. analysed the data. D.G., H.D., Q.G.T., B.V., J.G., H.A. contributed to interpretation of data and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving study participants were approved by the Queensland University of Technology Human Research Ethics Committee (1500000028). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients.

Supplementary Material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org.10.1017/S136898001900418X.