Food insecurity is inadequate access to nutritious food due to lack of resources(Reference Coleman-Jensen, Rabbitt and Gregory1). In 2018, 11 % of US households experienced food insecurity at some point during the year. The prevalence of food insecurity is even greater among households with children (14 %), single mother/father households (28 %/16 %), households with incomes below 185 % of the poverty threshold (29 %) and Black (21 %) and Hispanic (16 %) households(Reference Coleman-Jensen, Rabbitt and Gregory1). Food insecurity is associated with negative health outcomes for children, non-senior adults and senior adults(Reference Gundersen and Ziliak2). The most prevalent mental health state associated with food insecurity is depression and depressive symptoms(Reference Maynard, Andrade and Packull-McCormick3). The relationship between food insecurity and depression is particularly strong among women(Reference Heflin4–Reference Sharpe, Whitaker and Alia8) and mothers(Reference Hernandez9–Reference Munger11). Depression in women peaks during pregnancy and early motherhood(Reference Dietz, Williams and Callaghan12), and approximately 10–20 % of mothers experience depression at some point in their lives(13). Further, maternal depression is known to have lasting consequences on children. These include poorer health(Reference Casey, Goolsby and Berkowitz14), delayed language development(Reference Stein, Malmberg and Sylva15) and behaviour problems such as aggression, hyperactivity and emotional difficulties(Reference Narayanan and Naerde16–Reference Leschied, Chiodo and Whitehead18).

Several cross-sectional studies have demonstrated a positive association between food insecurity and maternal depression(Reference Whitaker17,Reference Bronte-Tinkew, Zaslow and Capps19–Reference Zekeri22) . In addition, longitudinal studies have begun to provide a better understanding of the relationship between food insecurity and depression(Reference Wu10,Reference Munger11) . For instance, Munger et al. (Reference Munger11) found that maintaining a status of food insecurity or becoming food insecure over a 2-year period increased the probability of mothers experiencing depression over time. However, for families that became food insecure and participated in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program was found to buffer the positive association between food insecurity and maternal depression.

On the other hand, some studies have shown that maternal depression contributes to food insecurity(Reference Hernandez9,Reference Casey, Goolsby and Berkowitz14,Reference Noonan23–Reference Laraia27) . While most studies have focused on the cross-sectional relationship, two studies using data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort examined the longitudinal relationship using various methodology. Both studies concluded that maternal depression was associated with elevated household food insecurity 15 months later(Reference Noonan23,Reference Garg, Toy and Tripodis25) . In summary, the temporal directionality of the association between food insecurity and maternal depression remains unclear. It is unknown whether food insecurity precedes maternal depression or vice versa as there is theory and literature to support each potential pathway.

The social vulnerability perspective can be applied to identify mothers most at risk for experiencing food insecurity and depression(Reference Andrew and Keefe28,Reference Cutter, Boruff and Shirley29) . While the social vulnerability perspective has consistently been used to study the impact of disasters or environmental hazards on health(Reference Peek and Stough30), the impact of experiencing chronic economic deprivation or poor mental health does not differ from experiencing a disaster. In both situations, vulnerability arises from limited or lack of social and economic resources(Reference Morrow31). Thus, the social vulnerability perspective suggests that a mother’s social situation can be influenced by socio-economic factors, such as food insecurity, which can perpetuate health problems, such as depression. This is similar to the food inadequacy hypothesis, which is used to describe limited household resources, such as food insecurity, as a contributor of maternal depression(Reference Wu10). On the other hand, a lack of resources needed to address depression could then exacerbate food insecurity experiences. For instance, grocery shopping and engaging in meal preparation may be difficult for mothers with depression(Reference Casey, Goolsby and Berkowitz14,Reference Melchior, Caspi and Howard26) . Depressed mothers may be incapable of properly managing their children’s meals due to fatigue associated with depression(Reference Leschied, Chiodo and Whitehead18). Finally, depression may impact a mother’s ability to obtain and maintain a stable income, which precludes worrying about where the next meal will come from(Reference Corman, Curtis and Noonan24,Reference Lerner and Henke32) . Thus, the mental health hypothesis states that the lack of household resources (i.e., food insecurity) is a consequence of maternal depression(Reference Wu10).

Studies evaluating the temporal directionality of the relationship between food insecurity and maternal depression are limited(Reference Huddleston-Casas33). Using the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study Birth Cohort, Wu et al. (Reference Wu10) found that food insecurity mediated the relationship between socio-economic status and maternal depression, but maternal depression did not mediate the relationship of socio-economic status and food insecurity. Their findings supported the food inadequacy hypothesis (not the mental health hypothesis) among mothers residing in suburban and rural areas. On the other hand, Huddleston-Casas et al. (Reference Huddleston-Casas33) found a recursive relationship between food insecurity and depression over a 2-year period among low-income mothers residing in a rural area. While food insecurity and poverty are more prevalent in rural areas(34), research is lacking on investigating the directionality between food insecurity and maternal depression among urban, socio-economically disadvantaged mothers.

Using an urban sample of socio-economically disadvantaged mothers, who are at increased risk for experiencing food insecurity and depression(Reference Morrow31), we evaluated the temporal directionality of the association between food insecurity and maternal depression over a 2-year period. Based on the research that supports the food inadequacy hypothesis where food insecurity predicts maternal depression(Reference Wu10), research that supports the mental health hypothesis where depression predicts food insecurity(Reference Noonan23,Reference Garg, Toy and Tripodis25) and prior research that used an rural sample indicates a bidirectional relationship exists(Reference Huddleston-Casas33), we hypothesised that there is a bidirectional relationship between food insecurity and depression among an urban sample of socio-economically disadvantaged mothers. In other words, we expected that food insecurity would predict subsequent maternal depression and that maternal depression would predict subsequent food insecurity. Understanding the directionality of this relationship will inform programmes aimed at reducing rates of food insecurity or maternal depression.

Methods

Data

The current study data originated from the longitudinal Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing study, which comprised 4898 children born between 1998 and 2000 in twenty cities across the USA. By design, 75 % of the children were born to unmarried parents. In the original study, mothers and fathers were interviewed after the birth of the focal child in the study and then again when the child was 1, 3, 5, 9 and 15 years old (i.e., waves 1–6). In addition to the main interview survey, a subsample of mothers were assigned to an in-home assessment when the child was 3 and 5 years old. The in-home assessment included questions regarding household food insecurity that were not assessed in the main interview survey. Sampling and study design have been previously reported(Reference Reichman, Teitler and Garfinkel35). The current study used data from wave 3, which corresponds when the child was 3 years old (considered time 1), and wave 4, which corresponds when the child 5 years old (considered time 2), and demographic variables collected only at baseline (e.g., race), which corresponds with the timing of the birth of the child. The sample consisted of 4897 mothers; one participant was excluded from the analyses due to missing data on all variables of interest.

Mothers with missing data differed from those with complete data on all variables of interest in several ways. Overall, mothers with missing data had higher levels of food insecurity at time 1 and time 2 (P < 0·05). A lower proportion of mothers with missing data were White or a race/ethnicity other than Black or Hispanic (P < 0·05), and a greater proportion were Black (P < 0·001). A lower proportion of the mothers with missing data were married/cohabitating with a new partner (P < 0·001); a greater proportion had less than a high school education (P < 0·001). A greater proportion of mothers with missing data were in the lowest federal poverty level (FPL) category (P < 0·001), and a lower proportion were in the highest FPL categories: FPL 2·00–2·99 (P < 0·05) and FPL ≥ 3·00 (P < 0·001). A greater proportion of mothers with missing data had public health insurance (P < 0·001); a lower proportion had private health insurance (P < 0·001). Incarceration of the focal child’s father was more common among those with missing data (P < 0·001) than those with complete data on all variables of interest.

Measures

Maternal depression

Maternal depression at time 1 and time 2 was determined from mothers’ responses to the fifteen-item Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Short Form(Reference Kessler, Andrews and Mroczek36). The Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Short Form helps to determine major depression status based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition(37). Example items in the Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Short Form include feeling sad/blue, having low energy or fluctuations in weight without trying during a 2-week period within the past 12 months. The Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing research team scored the Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Short Form and categorised whether women experienced depression or not(38).

Food insecurity

The household food security level was measured at time 1 and time 2 from mothers’ responses to the eighteen-item USDA Household Food Security Survey Module questionnaire(Reference Coleman-Jensen, Rabbitt and Gregory1). The scale determines food insecurity status by asking questions about food hardships related to a lack of financial resources or running out of food in the past 12 months(Reference Bickel, Cristofer and William39). Mothers with fewer than three affirmative responses were classified as food secure, and mothers who gave three or more affirmative response were categorised as food insecure(Reference Coleman-Jensen, Rabbitt and Gregory1).

Covariates

Covariates known to be related to both food insecurity and maternal depression were included in the analyses. Covariates included: teen mom status (teen mom (reference) v. not a teen mom (age ≥ 20 at focal child’s birth), race/ethnicity (White/other (reference), Black or Hispanic), nativity status (foreign born v. native born (reference)), marital status (single/divorced/widowed (reference) v. married/cohabitating), education (less than high school, high school or greater (reference)), employment status (employed v. unemployed (reference)), household income based on the family income in relation to the federal poverty line (FPL) (FPL ≤ 0·99 (reference), 1·00–1·99, 2·00–2·99; FPL ≥ 3·00) health insurance (public health insurance (reference), private health insurance or uninsured), paternal incarceration (father has been incarcerated since child’s birth v. father has not been incarcerated (reference)), child behaviour problems score (continuous)(Reference Achenbach40), parenting stress (continuous)(Reference Abidin41) and co-parenting support (continuous)(Reference Choi and Becher42). The mother’s status as a teenager at the focal child’s birth, along with her race/ethnicity, and nativity status were measured at baseline. All other covariates were assessed at time 1. The Department of Health and Human Services issues the FPL based on annual average estimates of the cost to cover basic needs. Income level for each participant was calculated by the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing team where self-reported annual household income by the FPL corresponded to the number of individuals residing in the household.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the full sample and by food insecurity and depression status at time 1. Independent samples t tests and χ 2 analysis were used to determine differences by food insecurity and depression status using Stata se statistical software version 15.0 (StataCorp). Two structural equation models were used to evaluate the impact of food insecurity on maternal depression (model 1) and the impact of maternal depression on food insecurity (model 2). Socio-demographic characteristics, child behaviour problems and parenting characteristics were included as covariates in all models to control for factors that may be related to food insecurity and maternal depression. In addition, models predicting depression (time 2) controlled for prior depression status (time 1) and concurrent food insecurity status (time 2); models predicting food insecurity (time 2) controlled for prior food insecurity status (time 1) and concurrent depression status (time 2). OR and unstandardised estimates are presented. Structural equation models were conducted in Mplus version 8.3 (Muthen & Muthen). The current study utilised fully saturated models to test our hypotheses informed by the literature; as such, model fit statistics are not available. Full information maximum likelihood was utilised to account for missing data.

Results

Sample characteristics

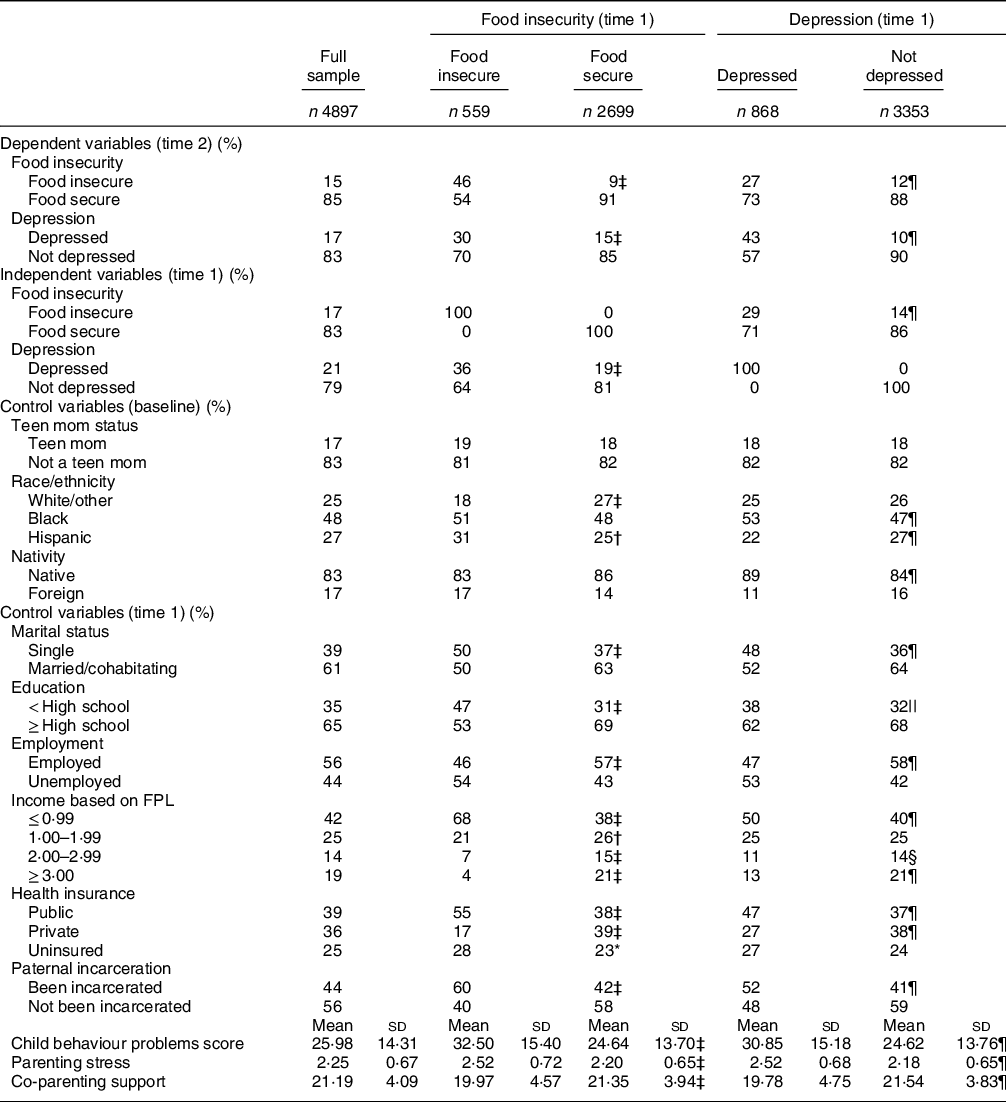

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the full analytic sample, by food security status and by depression status. At time 1, 17 % of the mothers were food insecure and 21 % were depressed. At time 2, 15 % of the mothers were food insecure and 17 % were depressed. The majority of the mothers did not have the focal child as a teenager (83 %), were native born (83 %), were married/cohabitating (61 %), had a high school diploma or greater (65 %) and were employed (56 %). Forty-two percentage of mothers reported incomes of FPL ≤ 0·99. Most mothers reported that they had public health insurance (39 %), while 36 % had private health insurance and 25 % were uninsured. Almost half (44 %) of the mothers reported that the focal child’s father had been incarcerated. The average child behaviour problems score was 25·98 (sd 14·31), the average parenting stress score was 2·25 (sd 0·67) and the average co-parenting support score was 21·19 (sd 4·09).

Table 1 Descriptive statistics of sample and by food insecurity and depression status, M (sd) or %

* P ≤ 0·05;

† P ≤ 0·01;

‡ P ≤ 0·001 different from food insecure.

§ P ≤ 0·05;

|| P ≤ 0·01;

¶ P ≤ 0·001 different from depressed.

Independent samples t tests (continuous) and χ 2 analysis (dichotomous) were used to determine differences among mothers by food insecurity and depression status.

Families who were food insecure at time 1 were more likely to experience food insecurity at time 2 (46 % v. 9 %; P ≤ 0·001). Similarly, mothers who experienced depression at time 1 were more likely to experience depression at time 2 (43 % v. 10 %; P ≤ 0·001). Mothers who resided in food insecure households at time 1 were more likely to experience depression at time 2 (30 % v. 15 %; P ≤ 0·001). Mothers who were depressed at time 1 were more likely to experience food insecurity at time 2 (27 % v. 12 %; P ≤ 0·001).

In general, mothers residing in food insecure households were more disadvantaged than mothers residing in food secure households. Racial differences existed by food insecurity status; a lower proportion of mothers living food insecure households were White/other (18 % v. 27 %; P ≤ 0·001). Compared with mothers residing in food secure households, a greater proportion of mothers living in food insecure households were single (50 % v. 37 %; P ≤ 0·001), less educated (less than high school: 47 % v. 31 %; P ≤ 0·001), had lower employment rates (46 % v. 57 %; P ≤ 0·001), had lower incomes (FPL ≤ 0·99: 68 % v. 38 %; P ≤ 0·001), reported greater rates of public health insurance (55 % v. 38 %; P ≤ 0·001), were more likely to be uninsured (28 % v. 23 %; P ≤ 0·05) and had lower rates of private health insurance (17 % v. 39 %; P ≤ 0·001). Paternal incarceration was more common among mothers residing in food insecure households (60 % v. 42 %; P ≤ 0·001). Mothers living in food insecure households also reported more child behaviour problems (32·50 (sd 15·40) v. 24·64 (sd 13·70); P ≤ 0·001), greater parenting stress (2·52 (sd 0·72) v. 2·20 (sd 0·65); P ≤ 0·001) and less co-parenting support (19·97 (sd 4·57) v. 21·35 (sd 3·94); P ≤ 0·001) compared with mothers living in food secure households.

In general, mothers experiencing depression were more disadvantaged than mothers who were not depressed. Racial differences existed by depression status; a greater proportion of depressed mothers were Black (53 % v. 47 %; P ≤ 0·001), and a lower proportion of depressed mothers were Hispanic (22 % v. 27 %; P ≤ 0·001). A greater proportion of depressed mothers were native born (89 % v. 84 %; P ≤ 0·001). The proportion of single mothers was higher among those who were depressed (48 % v. 36 %; P ≤ 0·001). Depressed mothers had lower employment rates (47 % v. 58 %; P ≤ 0·001) and lower incomes (FPL ≤ 0·99: 50 % v. 40 %; P ≤ 0·001, FPL ≥ 3·00: 13 % v. 21 %; P < 0·001). Depressed mothers reported greater rates of public health insurance (47 % v. 37 %; P ≤ 0·001) and lower rates of private health insurance (27 % v. 38 %; P ≤ 0·001). Paternal incarceration was more common among depressed mothers (52 % v. 41 %; P ≤ 0·001). Depressed mothers reported more child behaviour problems (30·85 (sd 15·18) v. 24·62 (sd 13·76); P ≤ 0·001), greater parenting stress (2·52 (sd 0·68) v. 2·18 (sd 0·65); P ≤ 0·001) and less co-parenting support (19·78 (sd 4·75) v. 21·54 (sd 3·83); P ≤ 0·001) compared with their non-depressed counterparts.

Bidirectional analyses of the food insecurity–maternal depression relationship

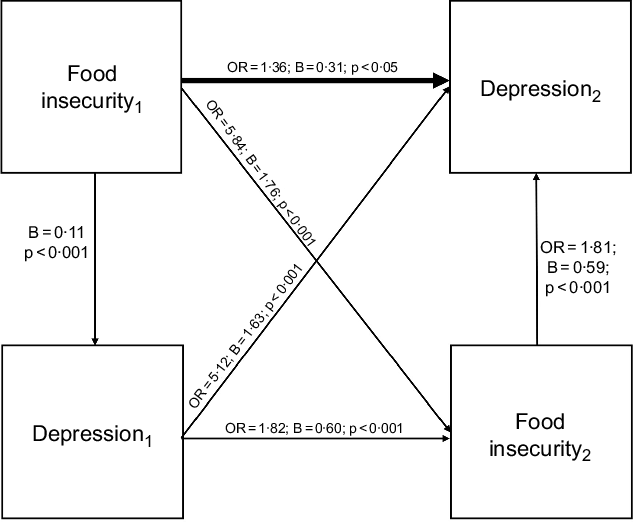

The model evaluating the food inadequacy hypothesis is depicted in Fig. 1. Food insecurity at time 1 was associated with 36 % increased odds (OR = 1·36; B = 0·31; P < 0·05) of maternal depression at time 2, controlling for prior depression status (OR = 5·12; B = 1·63; P < 0·001), concurrent food insecurity (OR = 1·81; B = 0·59; P < 0·001) and covariates (not pictured). Other paths in the model indicated that food insecurity at time 1 was a significant predictor of concurrent maternal depression (B = 0·11; P < 0·001). In addition, food insecurity (OR = 5·84; B = 1·76; P < 0·001) and maternal depression (OR = 1·82; B = 0·60; P < 0·001) at time 1 significantly predicted food insecurity at time 2.

Fig. 1 Model depicting food inadequacy hypothesis: food insecurity predicting maternal depression over a 2-year period (n 4897). Main path of interest is bolded in the figure. The following covariates were included in the analysis but not included in the figure: teen mom status, race/ethnicity native status, marital status, education, employment status, household income based on the family income in relation to the federal poverty line (FPL), health insurance, paternal incarceration, child behaviour problems score, parenting stress and co-parenting support. This is a fully saturated model; as such, model fit statistics are not available

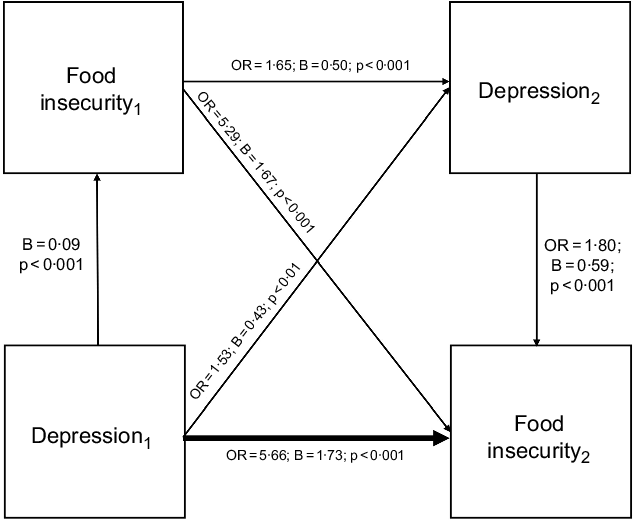

The model examining the mental health hypothesis is depicted in Fig. 2. Maternal depression at time 1 was associated with 53 % increased odds (OR = 1·53; B = 0·43; P < 0·001) of food insecurity at time 2, controlling for prior food insecurity status (OR = 5·66; B = 1·73; P < 0·001), concurrent depression (OR = 1·80; B = 0·59; P < 0·001) and covariates (not pictured). Additional paths in the model suggested that maternal depression at time 1 was a significant predictor of concurrent food insecurity (B = 0·09; P < 0·001). Maternal depression (OR = 5·29; B = 1·67; P < 0·001) and food insecurity (OR = 1·65; B = 0·51; P < 0·001) at time 1 significantly predicted maternal depression at time 2.

Fig. 2 Model depicting mental health hypothesis: maternal depression predicting food insecurity over a 2-year period (n 4897). Main path of interest is bolded in the figure. The following covariates were included in the analysis but not included in the figure: teen mom status, race/ethnicity native status, marital status, education, employment status, household income based on the family income in relation to the federal poverty line (FPL), health insurance, paternal incarceration, child behaviour problems score, parenting stress and co-parenting support. This is a fully saturated model; as such, model fit statistics are not available

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to evaluate the temporal relationship between food insecurity and maternal depression over a 2-year period. Our findings support our hypothesis that there is a bidirectional relationship between food insecurity and maternal depression(Reference Huddleston-Casas33). The results support both the mental health hypothesis and the food inadequacy hypothesis(Reference Wu10).

According to the mental health hypothesis, a lack of household resources (i.e., food insecurity) is a consequence of maternal depression. This can be explained through the ways in which depressive symptoms impact a mother’s ability to manage her family’s resources. Depressive symptoms such as fatigue may make necessary chores such as grocery shopping and meal preparation difficult for mothers(Reference Casey, Goolsby and Berkowitz14,Reference Leschied, Chiodo and Whitehead18,Reference Melchior, Caspi and Howard26,Reference Kaplan43) . Maternal depression likely has a large impact on the financial stability of the family, as it may inhibit mothers from obtaining and maintaining a stable income(Reference Corman, Curtis and Noonan24,Reference Lerner and Henke32) . Further the costs associated with managing depression (e.g., medical assistance, medication) may tax the family’s limited income, putting the household at increased risk of food insecurity.

Our findings also supported the food inadequacy hypothesis(Reference Wu10). Maternal depression was predicted by prior food insecurity experiences. This finding aligns with previous studies, which found that food insecurity was predictive of depression(Reference Wu10,Reference Munger11) . Overall, 46 % of those who were food insecure at time 1 remained so at time 2. Further, 74 % of mothers classified as depressed at time 1 remained so at time 2. The cumulative experiences of food insecurity and depression sustained over a period of time may impact mothers differently than acute exposure. This aligns with the accumulation of adversity model, which suggests that persistent exposure to adversity (e.g., food insecurity) over the life course places individuals at increased risk for negative health outcomes (e.g., depression)(Reference Evans, Chen and Miller44).

To our knowledge, only one previous study specifically aimed to assess the directionality of the relationship between food insecurity and maternal depression(Reference Huddleston-Casas33). Our research findings aligned with Huddleston-Casas et al. (Reference Huddleston-Casas33), who also found a bidirectional relationship between food insecurity and maternal depression. The results remained consistent despite differences in the study populations. Our sample consisted of urban, socio-economically disadvantaged mothers of young children (age 3 at time 1 and age 5 at time 2); Huddleston-Casas et al. (Reference Huddleston-Casas33) included a small sample of rural women with children under age 13. Food insecurity differs in urban compared with rural areas, with rural areas experiencing greater poverty and high rates of food insecurity(34). Additionally, differences in methodology existed. We used structural equation models to analyse two waves of data, whereas Huddleston-Casas et al. (Reference Huddleston-Casas33) used structural equation models to analyse three waves of data, and Wu et al.(Reference Wu10) used autoregressive cross-lagged models to analyse three to four waves of data. The consistency of these findings despite differing study populations and methodology strengthens our confidence in the results. However, future studies evaluating these relationships among a variety of demographically diverse study samples are needed to fully elucidate the temporal process of food insecurity and maternal depression.

The findings from the current study indicate that to adequately address food insecurity, maternal depression should also be addressed and to adequately address maternal depression, food insecurity should also be addressed. Simply providing mothers with access to additional food resources (such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children) may not be enough to adequately address and overcome food insecurity. If depressive symptoms prevent mothers from managing and preparing meals for their families, simply providing them with food is an inadequate strategy. A more holistic approach that combines mental health services with food resources may be necessary for mothers to improve depressive symptoms and manage/overcome food insecurity. Similarly, previous researchers found that access to food assistance programmes (e.g., Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) buffered the association between food insecurity and maternal depression(Reference Munger11). While our findings indicate that a holistic approach that combines food assistance and mental health services may better address food insecurity, additional studies are needed. Specifically, randomised controlled trials evaluating the efficacy of mental health services, food assistance programmes or a combination of both to address food insecurity and maternal depression are needed.

Strengths and limitations

The current study used a longitudinal approach to answer an important research question regarding the association between food insecurity and maternal depression. Understanding this relationship is necessary to protect this vulnerable population from depression and reduce its negative and long-lasting impact on children. However, the study did have some limitations. Due to the nature of secondary data, we were only able to include two time points, as food insecurity was only assessed at two time points. Future studies evaluating the relationship of food insecurity and maternal depression across multiple time points will give researchers more confidence in the pattern of this relationship. In addition, mothers self-reported on all the variables of interest. The findings may have been different if additional reporters had been included. Also, both main topics are of a sensitive nature and may be particularly prone to response bias. Nonetheless, the measures used to assess food insecurity(Reference Coleman-Jensen, Rabbitt and Gregory1) and maternal depression(Reference Kessler, Andrews and Mroczek36) are well established and accepted in the literature. Further, the study sample is not representative of all mothers as it only includes low-income urban mothers in the USA and purposive sampling was used by the parent study to oversample unmarried mothers. Findings may differ among mothers who are socio-economically or culturally different from the participants in this study. However, the findings are particularly relevant to this population who is at risk of experiencing food insecurity.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that there is a bidirectional relationship between food insecurity and maternal depression. This is an informative public health discovery because it indicates that incorporating food assistance programmes and mental health services may be beneficial for low-income mothers. Providing mothers seeking food assistance with information regarding accessing mental health services, in addition to screening for food insecurity and providing food assistance resources to low-income mothers seeking mental health services, may be a more efficacious approach to reducing chronic food insecurity as well as maternal depression.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01HD36916, R01HD39135 and R01HD40421, as well as a consortium of private foundations. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Conflict of interest: All authors declare no competing financial or personal relationships that could influence/bias this work. Authorship: All authors have substantially contributed to this manuscript, approved the final manuscript and are in agreement on the order of authorship. L.R.-O. conducted analyses, wrote the methods and results section, and assisted with the introduction and discussion. A.B.C. wrote the introduction and discussion. C.Y.L. assisted with data management and analyses. She provided edits to the final manuscript. X.Z. assisted with the development of the research question and provided edits to the final manuscript. D.C.H. developed the research question and oversaw all aspects of this manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the University of Houston. This manuscript involves the analyses of secondary data. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants by those who conducted the original study (cited within the manuscript).