Hypertension is a global public health issue. The total number of adults with hypertension reached 1·13 billion worldwide in 2015, up from 0·594 billion in 1975, and low- and middle-income countries contributed most to this increase(Reference Zhou, Bentham and Cesare1). The hypertension prevalence rate in China is increasing. A survey by Wang et al. in 2014 showed that the national adjusted hypertension prevalence rate was 29·6 %(Reference Wang, Zhang and Wang2), which was higher than that in 2002 (18 %)(Reference Wu, Huxley and Li3). Hypertension is an independent disease and an important risk factor for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. An investigation by the WHO on causes of death showed that about 17 million people die of CVD each year (which constitute about one-third of the total deaths); of all the cardiovascular causes of death, 47 % comprised heart disease and 54 % comprised stroke owing to hypertension(4,Reference Daskalopoulou, Rabi and Zarnke5) .

Dietary factors are closely related to the development of hypertension. A diet containing vegetables, fruits and low amounts of salt and fat helps to prevent or reduce hypertension. Excessive Na consumption is a risk factor for hypertension. Researchers are paying increasing attention to the association between dietary patterns and disease. The Mediterranean dietary pattern can lower hypertension(Reference Kastorini and Panagiotakos6) and chronic heart failure(Reference Chrysohoou, Pitsavos and Metallinos7). The Western dietary pattern is significantly associated with increased risk of maturity-onset CHD and stroke. Among different dietary patterns, the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) dietary pattern is generally recognized as an effective way to prevent and control hypertension. However, the DASH diet is not wholly appropriate for China, as it features fruits, vegetables, whole grains, other mineral-rich foods, low saturated fat consumption and low Na consumption(Reference Sacks, Svetkey and Vollmer8). The traditional dietary pattern in China(Reference Wang, He and Li9), particularly in northern China, is characterized by high consumption of wheat and starch and low consumption of protein products such as pork, beef, poultry, aquatic products and dairy products. This diet is very different from the DASH dietary pattern. In addition, the DASH dietary pattern focuses only on the effect of specific foods and nutrients on hypertension and does not consider the effect of overall dietary quality.

Located in northern China, Inner Mongolia is a minority community containing forty-nine ethnic groups, including the Han nationality and the Mongol nationality. Different ethnic groups have different genetic characteristics and food culture. Inner Mongolia has high prevalence rates for metabolic diseases related to nutrition, such as hypertension(Reference Li, Wang and Wang10). To address the relationship between diet and hypertension in Inner Mongolia, the association between dietary patterns and the prevalent risks of hypertension was explored in the present study. Chinese Dietary Balance Index-07 (DBI-07) scores were used to evaluate the quality of the main dietary patterns.

Methods

Study design

The present study was a surveillance survey of chronic disease and nutrition in Chinese adults in Inner Mongolia in 2015. The survey was conducted across eight monitoring sites in Inner Mongolia. Participants comprised residents of urban, farming, pastoral and forest areas, and from different age and ethnic groups. The cross-sectional study investigated dietary and non-dietary factors: general demographics, lifestyle, hypertension prevalence rate, dietary behavioural habits and daily food intake, by multistage-stratified cluster-random sampling among those aged ≥18 years.

The survey was approved by the Ethical Committee of the National Institute for Nutrition and Food Safety, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. All participants provided written informed consent before the start of the investigation.

Dietary data collection

A 24 h recall and weighing method over three consecutive days was used to collect dietary data. This dietary survey was recommended by the Chinese Dietary Guidelines for chronic disease and nutrition surveillance in Chinese adults, and aimed to know about the residents’ intakes of nutrients and foods. Every household member (aged 2 years or over) was investigated. In the 24 h recalls, participants recalled and described all food and alcohol consumption for three consecutive days. Information about consumption of condiments such as salt and soya sauce, and cooking oil, was collected using a weighing method. Condiments purchased and wasted were also recorded.

Drinking frequency, type (liquor with high alcohol content, liquor with low alcohol content, beer, yellow rice wine, rice wine, wine) and average drinking amount were measured. The average daily alcohol consumption was calculated according to the Manual of Chinese Chronic Disease and Nutrition Surveillance Survey(Reference Wang, Lay and Yu11). Participant height and weight were directly measured by trained and evaluated workers. Blood and urine samples were also collected. The laboratory director organized the quality-control sample assessment at a field laboratory.

Chinese Dietary Balance Index-07

The Chinese DBI-07 is a method for evaluating dietary structure and quality based on the Chinese Dietary Guidelines, which consists of seven components: (i) cereals; (ii) vegetables and fruits; (iii) dairy products, soyabeans and soyabean products; (iv) animal foods; (v) condiments and alcohol; (vi) dietary variety; and (vii) drinking-water(Reference Xu, Hall and Byles12,Reference Zang, Yu and Zhu13) . The DBI-07 evaluation of intake quality for different foods is based on the consumption patterns of individuals with different energy intakes. A score of 0 for each component indicates that the recommended intake has been met. Positive scores (0 to 12) are used to evaluate excessive intake of alcoholic beverages and condiments that should be reduced or limited according to the guidelines. Negative scores (−12 to 0) are used to evaluate insufficient intakes of vegetables and fruits, dairy products, soyabeans and soyabean products, food variety and drinking-water that should be consumed sufficiently or in quantity according to the guidelines. Both positive and negative scores are used to evaluate intake of cereals (−12 to 12) and animal foods (−12 to 8), which should be consumed in appropriate amounts according to the guidelines. To reflect the different nutritional needs of people with different energy consumption, the scores for cereals, vegetables, fruit, dairy products, soyabeans and soyabean products, animal foods and condiments are based on seven energy intake levels. Twelve food subgroups are used to evaluate the food variety recorded by the DBI-07: (i) rice and rice products; (ii) wheat and wheat products; (iii) corns, coarse grains, starchy roots and their products; (iv) dark-coloured vegetables; (v) light-coloured vegetables; (vi) fruits; (vii) soyabeans and soyabean products; (viii) dairy products; (ix) livestock meat and meat products; (x) poultry; (xi) eggs; and (xii) fish and shellfish. If food intake amounts meet the lowest recommended amounts, the score for this subgroup is 0; if not, −1. The lowest recommended intake amounts are 5 g for soyabeans and soyabean products and 25 g for other food subgroups. The score for food variety ranges from −12 to 0. An indicator of dietary quality is calculated from the scores on different parts of the DBI-07.

The higher-bound score (HBS) is calculated by adding all positive scores as an indicator of excessive food intake. The lower-bound score (LBS) is calculated by adding the absolute values of all negative scores as an indicator of insufficient food intake. Diet quality distance (DQD) is calculated by adding the absolute values of both positive and negative scores. The possible ranges for total score, HBS, LBS and DQD scores are −72 to 44, 0 to 32, 0 to 72 and 0 to 84, respectively. Each indicator is divided into five levels for convenience: (i) ‘no problem’ (a score of 0); (ii) ‘almost no problem’ (less than 20 % of the total score); (iii) ‘low level’ (20–40 % of the total score); (iv) ‘moderate level’ (40–60 % of the total score); and (v) ‘high level’ (>60 % of the total score). The total score of each DBI-07 component is divided by the total score of LBS, HBS and DQD to assess their contribution rate and how much each food subgroup affects dietary quality (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table S1).

Definition of hypertension

The main outcome indicator was hypertension. Meeting one of the following conditions was considered to indicate hypertension. The first condition was self-reported hypertension; that is, having a diagnosis of hypertension and currently receiving hypertension treatment(Reference Du, Yin and Wang14). The second condition was field-measured hypertension, assessed as the average of three blood pressure measurements carried out by trained investigators and defined as average systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and/or average diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg.

Other variables

Age was categorized as follows: <35, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64 and ≥65 years. Participant household registration place was categorized as urban or rural. Based on regional characteristics, ethnicity groups were categorized as Han, Mongolian or other minorities (i.e. all minorities living in Inner Mongolia except Han and Mongolian). Educational level was categorized as low (primary school or lower), medium (junior high school) or high (senior high school and above). Marital status was categorized as married, unmarried or widowed/divorced.

Smoking status was categorized as non-smoker (never having smoked previously), ex-smoker (previously smoked but has quit) or current smoker (has smoked at least 1 cigarette/d for more than 1 year and smokes now).

Physical activity was assessed by the questionnaire, which addressed three activity categories with twenty-six items: twenty items on physical activity state, four items on resting state and two items on sleeping state. The items asked participants what kind of activities they engaged in, the frequency of activities per week and the total time spent on activities per day. Physical activities were scored using the weighting procedure recommended by the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans(Reference Ainsworth, Haskell and Whitt15).

BMI was categorized as three groups according to the recommended standard issued by a working group on obesity in China(Reference Zhou16). BMI was categorized as normal or underweight (BMI < 23·9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI = 24·0–27·9 kg/m2) or obese (BMI ≥ 28·0 kg/m2). The normal and underweight categories were combined into one as there were too few people in the standard underweight category.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were shown as means and standard deviations. ANOVA was used for group comparisons. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages and were analysed using the χ 2 test.

Principal components analysis was used to derive food patterns based on the twenty-nine food groups. The varimax rotation (orthogonal rotation) was used to extract factor loadings. Factors were selected based on their eigenvalues (>1·00). The number of dietary patterns was determined based on scree plots, reasonability of food combination and variance contribution rate. Factor scores for each pattern were calculated by adding the coefficient of the factor loading and the standardized daily intake amounts of every kind of food that was related to each pattern. Dietary patterns were defined according to absolute factor loading values >0·2 for each factor on different food types. Dietary patterns were named by combining the food composition characteristics of the dietary pattern with the main food types included. Based on quartiles, factor scores were classified into four groups, quartiles Q1, Q2, Q3 and Q4, in ascending order of factor scores. The higher the score, the more consistent the individual dietary intake condition and dietary pattern were; the lower the score, the less likely the individual dietary intake condition fitted the dietary pattern.

Using generalized linear models, LBS, HBS, DQD being the dependent variables and dietary patterns being the independent variable, the quality of dietary patterns was evaluated after adjusting for other confounders. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to examine the association between dietary patterns and hypertension. The ‘Forward: LR’ method was used to select independent variables. With α = 0·05 as the significance level, P ≤ 0·05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics version 19.0 was used for all analyses.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 1861 participants were included in the present study: 889 (47·77 %) men and 972 (52·23 %) women. The mean age was 52·5 years. Of participants, 914 (49·11 %) were hypertension patients, 463 were male (52·08 %) and 451 were female (46·40 %). A total of 58·41 % of participants were from rural areas and 18·21 % were minorities; 45·89 % had primary school education or no formal education. Among the participants, the rate of excessive drinking was 3·39 %; 587 (31·54 %) and 109 (5·86 %) were identified as current smokers and ex-smokers, respectively; and 762 (41·41 %) were more likely partake in no exercise or inadequate exercise. The sex differences in marital status, weight control, salt control, dyslipidaemia and uric acid were significant (P < 0·05; see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table S2).

Dietary patterns

Four major dietary patterns, named the ‘high protein’ pattern, ‘traditional northern’ pattern, ‘modern’ pattern and ‘condiments’ pattern, were extracted (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Fig. S1). The total variance of these four dietary patterns was 27·754 %; the variance contribution rates were 9·017, 6·908, 6·645 and 5·184 %, respectively. Sex-specific dietary patterns are shown in Supplemental Tables S3 and S4 (Supplemental Figs S2 and S3). According to the variance, the order of the four major dietary patterns extracted was different between males and females, but the characteristics of food composition and the kinds of main foods in the four dietary patterns were basically the same. The ‘high protein’ pattern was characterized by milk tea and tea, fried wheat products, beef and mutton, milk and dairy products. The ‘traditional northern’ pattern represented a typical traditional diet: high intakes of starchy roots and products, pork, pickled vegetables/dried vegetables and corns. The ‘modern’ pattern featured the intake of various vegetables, fresh fruits, nuts and other foods. The ‘condiments’ pattern was characterized by high intakes of salt, animal oils, various condiments and various alcoholic beverages (Table 1).

Table 1 Factor loadings of each dietary pattern found among Inner Mongolia adults (n 1861), northern China, 2015

Characteristics of dietary patterns

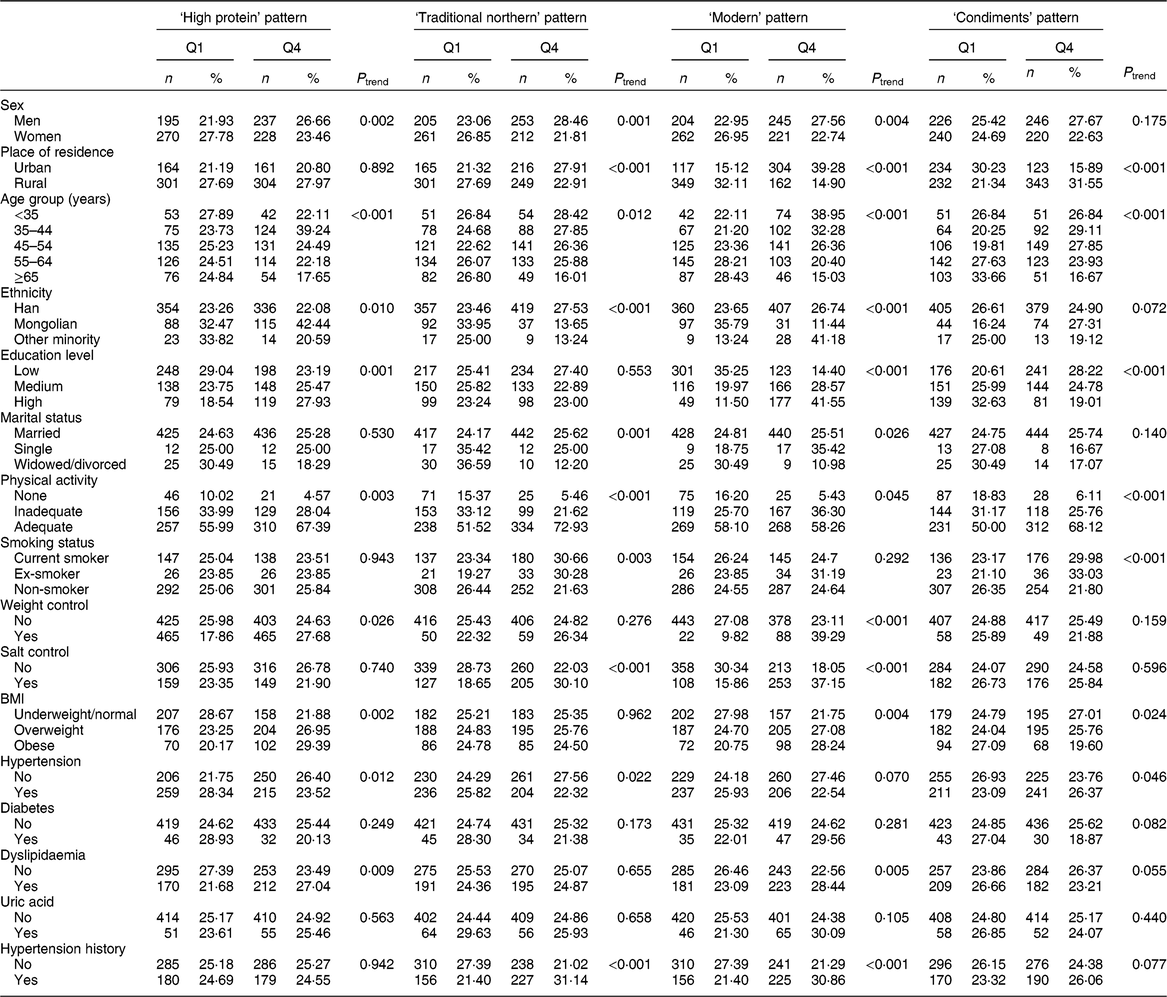

Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics of the four dietary patterns. The sex difference was significant in the distribution of the percentage in Q1 and Q4 of the ‘high protein’ pattern scores. There was an ascending trend for males and a declining trend for females (P trend = 0·002). Of those showing the ‘high protein’ pattern, participants were younger, had higher educational levels, showed greater weight control and a higher percentage were in Q4. Most of the participants in Q4 (67·39 %) showed the ‘high protein’ pattern and engaged in adequate physical activity. Increasing factor scores were associated with a higher percentage of overweight and obese participants (P trend = 0·002) and a lower percentage of hypertension patients (P trend = 0·012).

Table 2 Participant characteristics according to the lowest (Q1) and highest quartile (Q4) of each dietary pattern found among Inner Mongolia adults (n 1861), northern China, 2015

Participants with higher adherence to the ‘traditional northern’ pattern were from urban areas and were of Han nationality. Most were married, unlike those with low factor scores. There was a sex difference in the distribution of the percentages in Q1 and Q4 of the ‘traditional northern’ pattern; there was an ascending trend for males and a declining trend for females (P trend = 0·001). The proportion of participants in Q4 decreased with increasing age (P trend = 0·012); the ≥65 years group had the lowest percentage (16·01 %). Non-smokers showing the ‘traditional northern’ pattern were more likely to have low factor scores. There was an ascending trend from Q1 to Q4 in the percentages of participants who controlled their salt intake, but hypertension patients showed the opposite trend.

Participants with higher adherence to the ‘modern’ pattern were male and from urban areas. They were younger than those who had low factor scores on the ‘modern’ pattern. Fewer older participants were in Q4 (P < 0·01); those aged ≥65 years had the lowest percentage (15·03 %). Participants from other minorities had the highest percentage in Q4 (41·18 %). An ascending trend in the percentage in Q4 was observed as education level increased (P < 0·01). Participants with high factor scores on the ‘modern’ pattern engaged in adequate physical activity and many did not control their weight.

Participants with higher adherence to the ‘condiments’ pattern were ethnic Mongolian males from rural areas. They had lower education levels, most were aged 35–54 years and they were more likely to smoke. An ascending trend in the percentage in Q4 was associated with an increased level of physical activity (P trend < 0·001). The percentage of people who controlled their salt intake and the percentage of hypertension patients increased from Q1 to Q4.

Nutrient and energy intakes by dietary pattern

Table 3 compares nutrient intakes in the four dietary patterns by sex. In the ‘high protein’ pattern, the intake of Ca was highest in males and females. Additionally, the percentage of energy from protein was also higher. However, the percentage of energy from dinner was lowest. Among the four dietary patterns, intakes of nutrients such as total fat and K were highest in the ‘traditional northern’ pattern in both sexes. In the ‘modern’ pattern, the intake of carbohydrates was highest in both males and females. Additionally, the percentage of energy from carbohydrates was also higher. Among the four dietary patterns, Na intake and the percentage of the energy from dinner were highest in the ‘condiments’ pattern in both sexes. However, the intakes of Ca and dietary fibre were lowest. The food consumption in the four dietary patterns by sex is shown in the online supplementary material, Supplemental Table S5.

Table 3 Sex-specific nutrient and energy intakes according to the lowest (Q1) and highest quartile (Q4) of each dietary pattern found among Inner Mongolia adults (n 1861), northern China, 2015

* Compared with Q1, the mean ± sd is lower than the reference range.

† Compared with Q1, the mean ± sd is higher than the reference range.

Quality evaluation of food intake using Dietary Balance Index-07 scores

The distribution of dietary quality among Inner Mongolian adults is shown in the online supplementary material, Supplemental Table S6. In the total population, moderate- and high-level dietary imbalance accounted for 79·64 %. Among them, the distribution of LBS indicated that 26·90 % of the participants had high level of inadequate intakes, and the distribution of HBS indicated that 1·10 % of the participants had high level of excessive intakes. The mean scores of LBS, HBS and DQD were 37·54, 4·73 and 42·26, respectively. Participants with hypertension had higher scores in LBS and DQD.

Quality evaluation of dietary patterns using Dietary Balance Index-07 scores

The quality of the ‘high protein’ pattern was higher as evaluated by DBI-07. Participants with higher factor scores in the ‘high protein’ pattern had lower DBI-07 scores: LBS (β = −1·993; 95 % CI −2·362, −1·625; P < 0·001), HBS (β =−0·206; 95 % CI −0·381, −0·030; P = 0·021) and DQD (β = −2·199; 95 % CI −2·598, −1·801; P < 0·001). The quality of the ‘condiments’ pattern was lower. Participants with higher factor scores in the ‘condiments pattern’ had higher DBI-07 scores: LBS (β = 0·967; 95 % CI 0·570, 1·364; P < 0·001), HBS (β = 0·751; 95 % CI 0·570, 0·933; P < 0·001) and DQD (β = 1·718; 95 % CI 1·293, 2·143; P < 0·001). Higher adherence to the ‘traditional northern’ pattern was with lower LBS and higher HBS and DQD, and higher adherence to the ‘modern’ pattern was with lower LBS, DQD and higher HBS, respectively, which indicates diet quality was lower (Table 4). The results of evaluation of dietary quality in the different dietary patterns are shown in the online supplementary material, Supplemental Table S7.

Table 4 Generalized linear models* of dietary quality according to indicators of the Chinese Dietary Balance Index-07 (DBI-07) for each dietary pattern found among Inner Mongolia adults (n 1861), northern China, 2015

LBS, lower-bound score; HBS, higher-bound score; DQD, diet quality distance.

* Model adjusted for sex, age, place of residence, educational level, marital status, nationality, salt intake control, smoking status, weight control, BMI, hypertension, abnormal blood lipids and other variables.

Association between dietary patterns and hypertension

The ‘high protein’ pattern showed statistically significant inverse associations with hypertension in males, but no associations in females. In males, after adjusting for demographic and behavioural characteristics, the OR for hypertension in the highest quartile compared with the lowest was 0·406 (95 % CI 0·268, 0·615; P trend = 0·001); after further adjustment for BMI, the OR still less than 1, 0·374 (95 % CI 0·244, 0·573; P trend < 0·001). The ‘condiments’ pattern showed statistically significant positive associations with hypertension both in males and females. In males, after adjusting for demographic and behavioural characteristics and BMI, the OR for hypertension in the highest quartile compared with the lowest was 1·663 (95 % CI 1·113, 2·483; P trend = 0·005). In females, after adjusting for demographic and behavioural characteristics, the OR for hypertension in the highest quartile compared with the lowest quartile was 1·634 (95 % CI 1·067, 2·502; P trend = 0·037). After further adjustment for BMI, the OR increased to 1·788 (95 % CI 1·155, 2·766; P trend = 0·015). No associations between other dietary patterns and hypertension were observed (Tables 5 and 6).

Table 5 Association of dietary patterns with hypertension across quartiles (Q) of dietary pattern scores in male Inner Mongolia adults (n 889), northern China, 2015

Data were analysed using multivariable-adjusted logistic regression.

Model 1: crude model.

Model 2: adjusted for age place of residence, ethnicity, marital status, educational level, family history and dyslipidaemia.

Model 3: additionally adjusted for smoking status, physical activity, weight control and salt control.

Model 4: additionally adjusted for BMI.

Table 6 Association of dietary patterns with hypertension across quartiles (Q) of dietary pattern scores in female Inner Mongolia adults (n 972), northern China, 2015

Data were analysed using multivariable-adjusted logistic regression.

Model 1: crude model.

Model 2: adjusted for age, place of residence, ethnicity, marital status, educational level, family history and dyslipidaemia.

Model 3: additionally adjusted for smoking status, physical activity, weight control and salt control.

Model 4: additionally adjusted for BMI.

Discussion

The prevalence of hypertension was 49·11 % in Inner Mongolia, which is higher than the rate reported in northern China(Reference Yanlei, Zengwu and Xin17) and a national survey(Reference Wang, Zhang and Wang2). Lower diet quality as evaluated by DBI-07 was prominent in Inner Mongolia. Epidemiological evidence shows that the risk of hypertension is associated with sociodemographic, lifestyle, behavioural, genetic and dietary factors(Reference Horn, Tian and Neuhouser18,Reference Hong, Li and Wang19) , especially closely with dietary quality. The present cross-sectional study aimed to explore the association between the risk of hypertension and dietary quality as evaluated by the Chinese DBI-07 in Inner Mongolia in 2015.

Many studies(Reference Saneei, Salehi-Abargouei and Esmaillzadeh20,Reference Siervo, Lara and Chowdhury21) have suggested that the DASH dietary pattern can prevent and control hypertension. The DASH diet mainly recommends the consumption of whole-wheat bread, spinach salad, olive oil, aquatic products and other foods. Inner Mongolia is located in northern China, and for geographical and economic reasons, residents consume small amounts of fresh vegetables and fruit. Although the consumption of fresh vegetables and fruit has increased in recent years, consumption remains lower than the recommended amount. A food culture that features meat as the main component still exists among local residents. Additionally, a large amount of alcohol consumption is associated with an increased risk of hypertension for males, particularly Asians, which is also a major feature in Inner Mongolia. Therefore, the DASH dietary pattern is not appropriate for evaluating the dietary quality of people in Inner Mongolia. Ultimately, we chose the Chinese DBI-07 to evaluate the dietary quality of residents in Inner Mongolia. Distinct from the DASH dietary pattern, the DBI-07 considers the effect of alcohol consumption. Moreover, the DBI-07 is based on the recommended amounts of various foods from the Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents. The DBI-07 evaluated the quality of different food intakes based on the consumption patterns of individuals with different energy intake needs. Compared with the recommended intakes of the Chinese Dietary Guidelines (2016)(Reference Yang and Zhang22), the lower quality diet of Inner Mongolia residents was serious, especially the inadequate intakes.

The characteristics of food composition and the kinds of main foods in each of the four dietary patterns extracted were basically the same by sex. Therefore, we named them as ‘high protein’ pattern, ‘traditional northern’ pattern, ‘modern’ pattern and ‘condiments’ pattern in both sexes. And the cumulative variance of these four dietary patterns was 27·754 %, which is close to that found in other research(Reference Gao23,Reference Kim, Ji and Jung24) .

The ‘high protein’ pattern was characterized by milk tea and tea, fried wheat products, beef and mutton, milk and dairy products. The LBS, HBS and DQD indicators of DBI-07 showed a descending trend as the factor scores increased in the ‘high protein’ pattern. The dietary intake of meat and dairy products, and the intakes of nutrients such as protein and Ca, were higher than in the other dietary patterns. The energy intake at dinner was lower than for the other patterns. Male participants who mainly adhered to the ‘high protein’ pattern had a lower risk of hypertension, while in females the ‘high protein’ pattern was not significantly associated with hypertension. The possible reason is that intakes of protein and Ca, which benefited to control blood pressure(Reference Buendia, Bradlee and Singer25,Reference Teegarden26) , were lower in females than in males. In addition, the ‘high protein’ pattern in the present study was not the main dietary pattern in females, but the ‘traditional northern’ pattern. Other authors(Reference Wang27,Reference Zhao, Chu and Zhao28) also showed that a dietary pattern high in protein was associated with a reduced risk of hypertension. Although the intake of meat is a risk factor for hypertension(Reference Conlin, Chow and Miller29–Reference Rohrmann, Overvad and Bueno-de-Mesquita31), our study did not show that the ‘high protein’ dietary pattern with consumption of beef and mutton was a risk factor for hypertension after adjusting for confounders. On one hand, the fat content of beef and mutton is lower than that of pork(Reference Ekpo, Udofia and Eshiet32), and the other hand, dairy products are rich in protein and Ca. The high intake of protein makes people feel full quickly, which helps to eat less high-energy foods and improves the whole dietary quality to reduce blood pressure(Reference Buendia, Bradlee and Singer25,Reference Martini and Wood33) . Moreover, Ca contributes to reduce the incidence of obesity through shifting the energy balance, thereby reducing the risk of suffering hypertension(Reference Teegarden26). A notable feature of the ‘high protein’ dietary pattern was the high intake of milk tea and tea; of them, tea has a positive effect on blood pressure and blood lipids(Reference Li, Li and Wang34).

The ‘condiments’ pattern was characterized by high intakes of salt, animal oil, condiments and alcoholic beverages. The LBS, HBS and DQD indicators of DBI-07 showed an ascending trend as the factor scores increased. In the ‘condiments’ pattern, the dietary intake of oil and salt was higher than the recommended intake, and the dietary intake of vegetables, eggs and dairy was lower than the recommended intake. Participants had a higher risk of hypertension in the ‘condiments’ pattern. Factor score in the ‘condiments’ pattern was positively correlated with waist and lipid-related indicators, and thus it was also positively correlated with the prevalence of hypertension(Reference Zhu, Fang and Yang35,Reference Zhao36) . It is worth noting that the intake of alcohol in the ‘condiments’ dietary pattern is much higher than in the other three dietary patterns. Long-term excessive intake of alcohol is an independent risk factor for hypertension(Reference Roerecke, Tobe and Kaczorowski37,Reference Wood, Kaptoge and Butterworth38) . Participants with higher adherence to the ‘condiments’ pattern had the highest HBS for alcohol consumption and the highest risk of hypertension. Dietary salt and Na intakes were also the highest in the ‘condiments’ dietary pattern. Salt consumption is associated with hypertension(Reference Lei and Wang39,Reference Campagnoli, Gonzalez and Santa Cruz40) . Long-term excessive intake of salt reduces the ability of the kidneys to process salt(Reference Meneton, Jeunemaitre and Wardener41), leading to impairments of endothelial function, left ventricular relaxation, electric repolarization, endothelium dysfunction(Reference Tzemos, Lim and Wong42), and subsequent vascular sclerosis(Reference Bragulat, de la Sierra and Antonio43), resulting in primary hypertension by affecting Na loadings.

The ‘traditional northern’ pattern was characterized by high intakes of starch and sugar, pork, pickled vegetables/dried vegetables and corns; the dietary intake of cereals and meat was higher than the recommended intake, and the intakes of nutrients such as total fat and Na were also higher than recommended. The ‘modern’ pattern was characterized by the intakes of various vegetables, fresh fruits, nuts and other foods; the dietary intake of carbohydrates and Na was higher than the recommended intake, and intakes of the nutrients dietary fibre and Ca were lower than those recommended. In the ‘traditional northern’ pattern, the HBS and DQD indicators of DBI-07 ascended with increasing factor scores, although the LBS showed a descending trend. In the ‘modern’ pattern, HBS showed an ascending trend as the factor scores increased, even though LBS and DQD showed a descending trend. In our study, no association was found with hypertension.

Excessive intake of salt and alcohol is related to the development of hypertension(Reference Silman, Locke and Mitchell44–Reference Kazim, Ansari and Husain47). In our study, salt consumption was excessive in the four major dietary patterns, as assessed by DBI-07. For those participants with higher factor scores in the ‘traditional northern’ pattern and the ‘modern’ pattern, although they have no higher Na intake as factor scores increased compared with the ‘high protein’ pattern and the ‘condiments’ pattern, we did not find they were related to a lower risk of hypertension. The ‘condiments’ pattern had the highest intake of alcohol compared with the other three dietary patterns and showed a risk factor for hypertension. And the alcohol consumption in the ‘high protein’ pattern was higher than in the ‘traditional northern’ pattern. However, participants had a lower risk of hypertension if they mainly followed the ‘high protein’ pattern. Based on the excessive salt intake in the four major dietary patterns, and the higher alcohol consumption in the ‘high protein’ pattern than in the ‘traditional northern’ pattern, only the ‘high protein’ dietary pattern indicated a reduced hypertension risk, we suggest that the quality of dietary pattern evaluated by DBI-07 may explain the important part effect on hypertension. Evidence to support this assumption comes from a Japanese study(Reference Roerecke, Tobe and Kaczorowski37), which indicated that the higher the dietary quality and the more high quality diet, the lower the hypertension risk.

There is a close relationship between BMI and hypertension(Reference Rahman, Williams and Mamun48). The present study focused on the relationship between the quality of dietary patterns and hypertension. In males, after adjusting for BMI, the OR of the ‘high protein’ pattern with higher quality and risk of hypertension changed from 0·406 (95 % CI 0·268, 0·615) to 0·374 (95 % CI 0·244, 0·573). In females, after adjusting for BMI, the OR of the ‘condiments’ pattern with lower quality and risk of hypertension changed from 1·634 (95 % CI 1·067, 2·502) to 1·788 (95 % CI 1·155, 2·766). After adjusting for BMI, the dietary quality was still the primary factor for hypertension.

Sociodemographic features generally affect people’s dietary pattern and quality(Reference Darmon and Drewnowski49). Our study mainly evaluated the relationship between the quality of current dietary patterns and hypertension. Therefore, demographic characteristics were only used as confounders for adjustment. We did not explore further their effect on the relationship between dietary patterns and hypertension in the present study.

The present study was cross-sectional. Despite effective methods of quality control, a certain amount of bias (including selection bias, information bias and other types of bias) is unavoidable and may have affected the representativeness of the sample and results. Although the study demonstrated a relationship between excessive/insufficient food intake and hypertension, and between dietary patterns and hypertension, causal relationships cannot be assumed. The findings offer some insights into the aetiology of the association between dietary patterns and hypertension; however, long-term follow-up studies are needed to determine if there is a causal relationship between these factors.

Conclusions

In summary, four major dietary patterns were identified; the ‘high protein’ pattern (a higher-quality dietary pattern as evaluated by DBI-07) was related to a decreased prevalent risk of hypertension, while the ‘condiments’ pattern (a lower-quality dietary pattern as evaluated by DBI-07) was related to an increased prevalent risk of hypertension.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors sincerely express appreciation to all the participants and to local colleagues. They thank Diane Williams, PhD, from Liwen Bianji, Edanz Group China (www.liwenbianji.cn/ac), for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript. Financial support: This study was supported by Inner Mongolia Science and Technology Project (Intelligent Health Monitoring and Modern Medical Information System Development Based on Internet of Things Technology). The funder had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None declared. Authorship: X.W. and P.W. conceived and designed the protocol. X.W. and A.L. conducted the statistical analysis and prepared the manuscript. M.D., J.W., W.W. and Y.Q. contributed to data collection. H.Z., D. Liu, X.N., L.J., R.S., D. Liang and R.W. participated in cleaning and analysing the data. X.W. and A.L. produced the final revised manuscript. P.W. reviewed the paper and approved its final version. All authors were involved in interpreting results, editing the manuscript for content and approved the final version of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Ethical Committee of the National Institute for Nutrition and Food Safety, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Written informed consent was provided by participants before the start of the investigation.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S136898001900301X