Nutrition before conception and during pregnancy is important for both the mother and growing fetus. Inadequate nutrition, particularly during the first trimester of pregnancy, restricts fetal growth( Reference Antal, Regoly-Merei and Varsanyi 1 – Reference Northstone, Emmett and Rogers 3 ) and has long-term consequences for the mother and child( Reference Derbyshire, Davies and Costarelli 2 – Reference Moore, Davies and Willson 5 ). Gestational hypertension and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) are the most common complications of pregnancy( Reference Sibai 6 , Reference Zhang, Liu and Solomon 7 ). These complications have been associated with an increased risk of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes( Reference Brown, Hague and Higgins 8 – Reference Roberts, Pearson and Cutler 11 ), including stroke, fetal growth restriction, premature birth and death( Reference Brown, Hague and Higgins 8 , Reference Roberts, Pearson and Cutler 11 – Reference Peters and Flack 14 ) for gestational hypertension; and development of type 2 diabetes, pre-eclampsia and fetal macrosomia( 15 ) for women with GDM. The leading causes of neonatal death among children born without congenital abnormalities are premature birth and low birth weight, with the majority of deaths occurring in developing countries( Reference Bhutta, Darmstadt and Hasan 16 ). Premature birth and low birth weight impose immediate and lifelong consequences in terms of physical and cognitive development, quality of life and health-care costs( 17 – Reference Abu-Saad and Fraser 24 ).

Maternal diet is one potential mediator of gestational hypertension( Reference Brantsæter, Haugen and Samuelsen 25 – Reference Thangaratinam, Rogozińska and Jolly 29 ), GDM( Reference Zhang, Liu and Solomon 7 , Reference King 26 , Reference Thangaratinam, Rogozińska and Jolly 29 , Reference Qiu, Zhang and Gelaye 30 ), premature birth( Reference Thangaratinam, Rogozińska and Jolly 29 – Reference Ota, Tobe-Gai and Mori 34 ) and low birth weight( Reference Gresham, Byles and Bisquera 35 , Reference Rees, Doyle and Srivastava 36 ). Worldwide, there are few studies( Reference Rifas-Shiman, Rich-Edwards and Kleinman 37 , Reference Xiao, Simas and Person 38 ) on maternal diet quality and the relationship with, or prevention of, adverse pregnancy outcomes. To our knowledge there are none in Australia. Morrison et al. examined diet quality postpartum in a national sample of women with a previous history of GDM( Reference Morrison, Koh and Lowe 39 ) and found that there was an association between poor diet quality postpartum and a history of GDM.

Diet quality refers to the nutritional adequacy and food variety of an individual’s dietary intake and its alignment with national dietary guidelines( Reference Ruel 40 , Reference Kant 41 ). Diet quality offers a broader view of food and nutrient intakes, as opposed to the study of single nutrients or foods. Scores or indices summarise dietary intake assessed by a variety of measures, such as FFQ( Reference Collins, Burrows and Rollo 42 ), into a single numerical value( Reference Burrows, Collins and Watson 43 ). The Australian Recommended Food Score (ARFS) is a previously validated tool that evaluates overall diet quality of adults( Reference Collins, Burrows and Rollo 42 ). The ARFS has been adapted for use in pregnancy previously as a way to measure overall diet quality in this population( Reference Hure, Young and Smith 44 ). The objective of the present study was to determine in a national sample of young Australian women whether diet quality before or during pregnancy predicts adverse perinatal outcomes including gestational hypertension, GDM, premature birth and low birth weight.

Methods

Data collection

The current study used self-reported data collected prospectively from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (ALSWH). The ALSWH recruited approximately 40 000 women in 1996 across three cohorts: those born in 1973–78 (18–23 years), 1946–51 (45–50 years) and 1921–26 (70–75 years). Women were randomly selected from Australia’s nationalised health-care system, Medicare, with intentional oversampling in rural and remote areas. Ethical approval was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committees of the Universities of Newcastle (H-076-0795) and Queensland (2004000224), with written informed consent provided by participants. Further details of the ALSWH recruitment and cohort profile have been published elsewhere( Reference Brown, Bryson and Byles 45 – Reference Brown, Bryson and Byles 47 ).

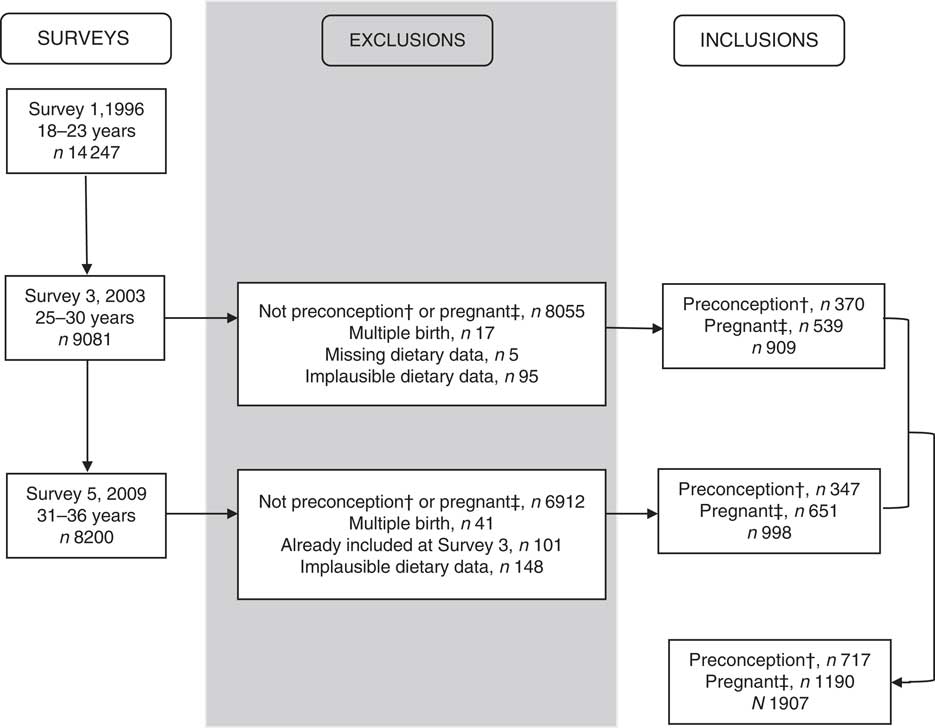

The present paper examines data from the 1973–78 cohort, who were broadly representative of Australian women the same age at the baseline survey( Reference Brown, Bryson and Byles 45 ). Paper-based surveys were mailed to participants in 1996 (Survey 1, 14 247 respondents), 2000 (Survey 2, n 9688), 2003 (Survey 3, n 9081) and 2006 (Survey 4, n 9145). In 2009 (Survey 5, n 8200) and 2012 (Survey 6, n 8009) participants could opt to complete the survey online or in hard copy. The current analysis includes all women with dietary data collected at either Survey 3 or 5 (with only one set of data contributing to the analysis), with pregnancy and birth outcome data collected at Survey 5 and 6. The ALSWH survey also included specific demographic and health behavioural measures including area of residence, marital status, level of education, self-reported health, parity, smoking, alcohol, frequency and intensity of physical activity, height and income.

Dietary assessment

FFQ

The Dietary Questionnaire for Epidemiological Studies (DQES) version 2, a seventy-four-item FFQ, was included in Surveys 3 and 5. This FFQ reports usual food and beverage intake for the previous 12 months (excluding vitamin and/or mineral supplementation) and has been validated against 7 d weighed food records in a cohort of young Australian women( Reference Hodge, Patterson and Brown 48 ).

Australian Recommended Food Score

The ARFS uses the DQES to summarise diet quality. Hure et al. have previously summarised the ARFS in the 1973–78 ALSWH cohort by pregnancy status and have shown more favourable nutrient intakes with increasing ARFS (i.e. better diet quality)( Reference Hure, Young and Smith 44 ). The development of the ARFS by Collins et al. has been described in detail elsewhere( Reference Collins, Young and Hodge 49 , Reference Collins, Hodge and Young 50 ). Briefly, the ARFS was modelled on the Recommended Food Score established by Kant and Thompson( Reference Kant and Thompson 51 ) in 1997. The calculation of the ARFS was based on the regular consumption of food items within the DQES whose intake is consistent with national recommendations in the Dietary Guidelines for Australian Adults( 52 ) and the core foods within the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating( Reference Smith, Kellett and Schmerlaib 53 ).

Each recommended food and beverage item that was reportedly consumed on average at least weekly scored 1 point. An additional point was allocated for specific types and amounts of core foods consumed based on the following: at least two servings of fruit daily; at least four servings of vegetables daily; weekly consumption of one to four servings each of beef, veal, lamb, pork, chicken and fresh or canned fish; using reduced-fat or skimmed milk; using soya milk; consuming at least 500 ml milk daily; using high-fibre, wholemeal, rye or multigrain bread; having at least four slices of bread daily; using polyunsaturated or monounsaturated spreads or no spread at all; consuming ricotta or cottage cheese; using low-fat cheese; consuming ice cream less than once weekly; consuming cheese less than once weekly; and consuming yoghurt at least once weekly. For the present analysis 1 point was allocated for having up to five eggs weekly, which is in line with the current recommendations by the National Heart Foundation( 54 , 55 ). There is no safe level of alcohol consumption during pregnancy( 56 ). Questions pertaining to alcohol consumption were removed from the present analysis, as we were unable to determine if women who were pregnant were reporting their pre-pregnancy intakes. Subsequently, the maximum ARFS that could be achieved was 72.

Sample

Women were aged 20–25 years at Survey 3 and 31–36 years at Survey 5, which both included the FFQ. Pregnancy status was classified as either preconception or pregnant. The woman’s survey return date and child’s date of birth were used to classify pregnancy status. Preconception included women who returned a survey 10–15 months before a child’s date of birth. Women were classified as pregnant if they returned a survey 0–9 months before a child’s date of birth. Each participant contributed only their first available preconception/pregnancy data.

Participants were excluded from the present analysis if: (i) they were not classified as preconception or pregnant when completing the FFQ (Survey 3, n 8055; Survey 5, n 6912); (ii) they had a multiple birth (Survey 3, n 17; Survey 5, n 41); or (iii) they did not complete the FFQ (Survey 3, n 5; Survey 5, n 0). A further 101 women had preconception and/or pregnancy data at both Surveys 3 and 5, so their Survey 5 data were excluded. Energy cut-off values recommended by Meltzer et al. were applied to the preconception and pregnancy groups, excluding those who reported daily energy intakes below 4·5 MJ/d or above 20·0 MJ/d( Reference Meltzer, Brantsæter and Ydersbond 57 ). Energy values outside this range were considered biologically implausible and indicative of misreporting (Survey 3, n 95; Survey 5, n 148). Energy from alcohol was not included in the reported total daily energy intakes.

Pregnancy and birth outcomes

Gestational hypertension, GDM, premature birth and low birth weight were the outcomes included in the present analysis. From Survey 4 onwards, women were asked ‘Did you experience any of the following?’ with ‘A low birth weight infant (weighing less than 2500 grams or

![]() $5{\raise0.7ex 1\over 2}$

pounds)’ and ‘Premature birth’ (no gestational cut-off specified) listed. From Survey 5 onwards, women were asked to recall for each child whether they had been diagnosed by a doctor or treated for ‘Hypertension (high blood pressure) during pregnancy’ or ‘Gestational diabetes’. For example, women reporting dietary data at Survey 5 had their pregnancy and birth outcomes taken from the next available survey (Survey 6). We have previously assessed the reliability of these self-reported reproductive outcomes against more objective medical records, showing very high agreement (≥92 %) between the two data sets(

Reference Gresham, Forder and Chojenta

58

).

$5{\raise0.7ex 1\over 2}$

pounds)’ and ‘Premature birth’ (no gestational cut-off specified) listed. From Survey 5 onwards, women were asked to recall for each child whether they had been diagnosed by a doctor or treated for ‘Hypertension (high blood pressure) during pregnancy’ or ‘Gestational diabetes’. For example, women reporting dietary data at Survey 5 had their pregnancy and birth outcomes taken from the next available survey (Survey 6). We have previously assessed the reliability of these self-reported reproductive outcomes against more objective medical records, showing very high agreement (≥92 %) between the two data sets(

Reference Gresham, Forder and Chojenta

58

).

Statistical analyses

The characteristics of women included in the study were compared with those who were not included. Means and standard deviations are presented for normally distributed continuous variables and proportions are presented for categorical variables. Frequencies of the pregnancy and birth outcomes, as well as the ARFS food component scores and total ARFS, were compared between preconception and pregnant women. Univariate analysis (t test) was performed to compare component scores and total ARFS for different reproductive outcomes, with its effect adjusted for all potential confounders (multivariable analysis), including body weight, smoking, education, parity, area of residence, exercise status and maternal age. ARFS results were ranked and divided into quintiles. The association between quintiles of the ARFS and pregnancy and birth outcomes as dichotomous variables was examined by multiple logistic regressions. Risks are presented as crude and adjusted odds ratios with 95 % confidence intervals. P values ≤0·05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using the statistical software package Stata IC, version 13.

Results

The selection of cohort participants eligible for inclusion in the present analysis is presented in Fig. 1. A total of 1907 women with plausible dietary data were included in the analysis. Table 1 summarises the baseline characteristics (reported in 1996) of women included in the analysis and for those in the remaining 1973–78 ALSWH cohort. Women included were the same age as those excluded (20·8 and 20·7 years, respectively), with the majority from both groups living in urban areas (56·2 % v. 55·1 %). At baseline, women included were more likely to be single, to have no children, and be less likely to smoke or drink alcohol at risky levels. While there was a similar number of women who attained school or high-school education, more women included in the current analysis reported university education (16·3 % v. 10·3 %).

Fig. 1 Attrition for women from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health 1973–78 cohort. †Preconception: women who returned a survey with a completed FFQ, 10–15 months before pregnancy. ‡Pregnant: women who returned a survey with a completed FFQ and reported that they were pregnant or were 0–9 months before pregnancy

Table 1 Baseline characteristics for the young cohort of the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health 1973–78 according to inclusion (n 1907) or not in the present study (n 12 340)

† Participant characteristics were taken from the baseline survey.

For the pregnancy and birth outcomes, 8 % (n 144) self-reported gestational hypertension; 4 % (n 83) reported GDM; 6 % (n 122) reported a premature birth; and 3 % (n 62) reported a low-birth-weight infant.

Comparisons of the total and component scores that make up the ARFS for women classified as preconception or pregnant indicated very few differences (not tested for significance; Table 2). Women who were pregnant scored half a point more for the fruit component, which mostly accounted for the difference in total ARFS by group (31·5 preconception v. 32·1 pregnant). Because there was no real difference in ARFS total or component scores the preconception and pregnancy groups were combined for the remaining analyses.

Table 2 Mean component scores and total Australian Recommended Food Score (ARFS) for women according to pregnancy status and energy intake in the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health 1973–78 cohort

Max, maximum; min, minimum.

† Preconception and pregnancy groups combined.

‡ Sub-components of the protein food category.

The univariate analyses between the ARFS and reproductive outcomes are reported in Table 3. Multivariate analysis was also applied to adjust for potential confounding from weight, smoking, education, parity, area of residence, exercise status and maternal age. Overall, women with gestational hypertension, compared with those without, had lower scores for the total ARFS and the vegetable, fruit, grain and nuts/bean/soya components, which all remained significant after adjustment. Women with GDM had a higher score for the vegetable component only, compared with women without GDM, which remained significant after adjustment. Women who had a low-birth-weight infant had a lower total ARFS, from lower vegetable and grain component scores, compared with those who did report low birth weight. The results for low birth weight remained significant after adjustment except that the vegetable component was of borderline significance (P=0·06). There were no significant associations between ARFS component and total scores and premature birth.

Table 3 Component scores and total Australian Recommended Food Score (ARFS) according to pregnancy and birth outcomes for womenFootnote † in the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health 1973–78 cohort

Max, maximum.

*P value is statistically significant at ≤0·05.

**P value is statistically significant at ≤0·01.

† Preconception and pregnancy groups combined.

The results of multiple logistic regression testing crude and adjusted associations between quintiles of ARFS and pregnancy and birth outcomes are summarised in Table 4. Women in the lowest quintile of diet quality (quintile 1) were used as the reference group. Women in quintile 5 had 60 % lower odds of developing gestational hypertension and delivering a low-birth-weight infant than women in quintile 1, before and after adjustment for potential confounders. A lower risk of gestational hypertension and delivering a low-birth-weight infant was observed in every quintile of ARFS compared with the reference quintile, with the exception of quintile 3 for gestational hypertension. Overall, diet quality by quintile was not associated with GDM or premature birth.

Table 4 Crude and adjusted associations between quintiles of the Australian Recommended Food Score (ARFS) and pregnancy and birth outcomes for women in the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health 1973–78 cohort

Ref., reference category.

*P value is statistically significant at ≤0·05.

**P value is statistically significant at ≤0·01.

† Adjusted for level of education, area of residence, smoking status, parity, age, weight and level of exercise.

Discussion

This is the first Australian study and the largest international study investigating the relationship between diet quality before or during pregnancy in a sample of Australian women in association with adverse outcomes gestational hypertension, GDM, premature birth and low birth weight. The current study demonstrates that lower diet quality (before or during pregnancy), based on a previously validated composite diet quality score, the ARFS, is associated with the development of gestational hypertension for the mother and low birth weight for the child. Moreover, women with the highest ARFS had the lowest risk of developing gestational hypertension or delivering a child of low birth weight.

Interpretation

The relationship between diet quality before and during pregnancy as measured by the ARFS and adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes has not been previously analysed in Australia. To our knowledge, Hure et al. and Morrison et al. are the only studies to evaluate diet quality in a national sample of young Australian women by pregnancy status( Reference Hure, Young and Smith 44 ) or with a history of GDM( Reference Morrison, Koh and Lowe 39 ), respectively. Both Hure et al. and Morrison et al. demonstrated that irrespective of pregnancy status( Reference Hure, Young and Smith 44 ) or past history of GDM( Reference Morrison, Koh and Lowe 39 ), young women at this life stage commonly have poor diet quality scores reflecting a failure to meet national dietary recommendations.

In the current study, analysis of the relationship between ARFS components and pregnancy and birth outcomes indicated that no individual ARFS components accounted for more than one whole point difference between women with and without adverse perinatal outcomes. Analysis by total ARFS demonstrated differences in mean scores of two points or more between women with and without gestational hypertension and those women who had a low-birth-weight infant or not. The most poorly scored food groups were protein (especially nuts/bean/soya) and grains, with nuts/bean/soya and grain components shown to be a predictor of gestational hypertension and grains a predictor of low birth weight. To achieve a higher grain score, and higher total ARFS, women would need to consume a greater variety of wholemeal, wholegrain and high-fibre breads and cereals, including rice, pasta and noodles, weekly or more often; while to achieve a higher score for the nuts/bean/soya component and hence higher total ARFS, women would need to include a greater variety of nuts, nut butter, baked beans, tofu, soya and other beans (i.e. lentils) at least once per week.

Worldwide, there are only a few other studies that examine the association between diet quality during pregnancy and pregnancy and birth outcomes( Reference Rifas-Shiman, Rich-Edwards and Kleinman 37 , Reference Carmichael, Shaw and Selvin 59 – Reference Rodríguez-Bernal, Rebagliato and Iñiguez 61 ). Similar to results in the current study, Rodríguez-Bernal et al. ( Reference Rodríguez-Bernal, Rebagliato and Iñiguez 61 ) observed a significant increase in newborn birth weight among women with better diet quality during the first trimester compared with infants born to women with the lowest diet quality scores (mean (sd): 3387·9 (399·5) v. 3218·1 (442·3) g). Rifas-Shiman et al. found a significant decrease in the risk of pre-eclampsia for each 5-point increase in diet quality during the second trimester only (OR=0·87; 95 % CI 0·76, 1·00)( Reference Rifas-Shiman, Rich-Edwards and Kleinman 37 ). Despite birth weight and pre-eclampsia not being direct outcomes in the current study, they give further strength to the relationship between diet quality and risk of developing gestational hypertension or delivering a low-birth-weight infant. Like the modified ARFS used in the current study, Rodríguez-Bernal et al. and Rifas-Shiman et al. excluded alcohol and multivitamin use when calculating their modified Alternate Healthy Eating Index scores. Two recent meta-analyses of dietary intervention trials (food, counselling or a combination of both) on pregnancy and birth outcomes have shown significant effects for a reduction in maternal blood pressure, incidence of preterm delivery( Reference Gresham, Bisquera and Byles 62 ), increase in birth weight and lower incidence of low birth weight( Reference Gresham, Byles and Bisquera 35 ), further highlighting the effect of diet during pregnancy and the potential to lower the incidence of adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes.

Implications for practice and research

The findings of the current study suggest that higher diet quality before or during pregnancy is associated with a lower risk of gestational hypertension for the mother and low birth weight for the infant. General practitioners are generally one of the first health professionals a woman consults when she is pregnant or trying to conceive. This initial consultation provides an ideal opportunity to assess a woman’s current dietary intake, identify those with or at risk of low diet quality, and create opportunities for the woman to receive dietary advice targeting improvements in diet quality as a practical strategy to reduce the risk of undesirable pregnancy and birth outcomes. A questionnaire to measure diet quality before or during pregnancy would be a much simpler tool with a lower participant and analytic burden than an FFQ that carries a high burden and costly analysis( Reference Collins, Young and Hodge 49 ). Health professionals, including general practitioners, obstetricians, midwives, dietitians and pharmacists, should encourage those women who are pregnant or considering pregnancy to consume a wide variety of nutritious foods, particularly vegetables, fruits, whole grains, nuts and legumes, dairy and lean animal proteins.

Large, high-quality randomised controlled trials focusing on diet quality before and during pregnancy on reproductive outcomes are also required. Dietary intervention trials should focus on a wide variety of nutrient-dense foods to achieve high diet quality.

Strengths and limitations

In comparison with national data (inclusive of all pregnant women regardless of age)( 63 ), women in the current study had a lower prevalence of GDM (11 % national data v. 4 % self-reported), premature birth (9 % v. 7 %) and low birth weight (6 % v. 4 %), with the same prevalence of gestational hypertension (8 %). The higher proportion of university-educated women in our sub-sample may account for some of this bias. We previously conducted an agreement study, demonstrating high agreement (≥87 %) between self-reported ALSWH and administrative data for the adverse outcomes gestational hypertension, GDM, preterm birth and low birth weight( Reference Gresham, Forder and Chojenta 58 ), offering a high degree of confidence in the accuracy of ALSWH self-report. Women diagnosed with gestational hypertension and/or GDM have been shown to develop complications in the infant such as premature birth or low birth weight. For the current analysis each pregnancy and birth outcome was examined separately. Future studies should include analyses that adjust for gestational hypertension and GDM when examining premature birth and low birth weight.

Like all tools used to measure dietary intake, the ARFS has limitations. Women are asked to report their usual consumption of foods over the preceding 12 months in the FFQ; therefore results may be influenced by the season in which the questionnaire is administered or be more likely to emphasise recently consumed foods. As the ARFS focuses on the frequency and variety of food choices, the scoring is independent of reported amounts of food items that would have reduced the associated measurement error. Under- and over-reporting may have occurred in the FFQ; however, an attempt to address this has been made by limiting analysis to those with plausible dietary intakes. Diet during pregnancy may also vary across trimesters. The present analysis assumes that diet remains constant, and there are some data supporting highly correlated intakes in early and late pregnancy( Reference Blumfield, Hure and MacDonald-Wicks 64 ).

Conclusion

The current study is the largest in Australia and internationally to investigate the association between diet quality during pregnancy and adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes. The current findings suggest that higher diet quality during pregnancy is associated with lower risk of gestational hypertension and favours fetal growth by decreasing the risk of delivering a low-birth-weight infant. The current brief diet quality questionnaire may be an appropriate tool to help health professionals identify women at risk of poor diet quality during pregnancy and provide an opportunity to intervene to lower the risk of adverse outcomes. Those who are pregnant or considering pregnancy should consume a wide variety of nutritious foods, particularly vegetables and fruits of different colours and types; wholemeal, wholegrain and high-fibre grain-based foods; nuts and legumes. High-quality randomised controlled trials that test strategies to improve diet quality and effects on pregnancy and birth outcomes are needed.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The research on which this paper is based was conducted as part of the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health, the University of Newcastle and the University of Queensland. The authors are grateful to the Australian Government Department of Health for funding and to the women who provided the interview data. The authors thank Professor Graham Giles, of the Cancer Epidemiology Centre of Cancer Council Victoria, for permission to use the Dietary Questionnaire for Epidemiological Studies version 2 (Cancer Council Victoria, Melbourne, 1996). Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: E.G. helped design the study, undertook the statistical analysis and was responsible for the project’s implementation, including the preparation of the manuscript. C.E.C. helped design the study and provided ongoing input. G.D.M. helped design the study and provided ongoing input. J.E.B. helped design the study and provided ongoing input. A.J.H. designed the study and provided ongoing input into the implementation, quality assurance and control aspects of the project. All authors were involved in revising the manuscript for important intellectual content and have made a significant contribution to the research and development of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Ethical approval was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committees of the Universities of Newcastle (H-076-0795) and Queensland (2004000224), with written informed consent provided by participants.