Since the 1500s, when the imperial powers of Europe sought to rapidly expand their empires through the colonisation of sub-Saharan Africa, ancient indigenous knowledge, including an incredible wealth of knowledge about food habits, health and longevity, has progressively wanedReference Mutwa1. Over the past several centuries, the methods implemented to excise this indigenous knowledge have generally shifted from the use of overt force (e.g. slavery, religious conversion, seizure of arable land and food supply)Reference Dugian, Gann and Turner2 to the implementation of a neocolonial, political–economic structure inherently designed to oppress through the creation of economic dependenceReference Cannon3–Reference Ayittey6.

The deleterious influence of these colonial and neocolonial forces in sub-Saharan Africa becomes glaringly evident with any legitimate inquiry into the root causes of the various disease epidemics currently afflicting the marginalised, indigenous people of this vast continent7. Over the past several decades, sub-Saharan Africa has experienced a rapid upsurge of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), which includes epidemics of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD) and various cancers7. Within the next 20 years, the region can expect a threefold increase in deaths due to CVD and a near threefold increase in the incidence of type 2 diabetesReference Wild, Roglic, Green, Sicree and King8. Further, NCDs have not replaced infectious and malnutrition-related diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: they coexist alongside classic nutritional deficiencies, famine and infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS, resulting in a polarised and protracted double burden of diseaseReference Popkin9–Reference Bourne, Lambert and Steyn12. By 2020, it is predicted that NCDs will account for 80% of the global disease burden, and will cause 70% of deaths in developing countries7. The health-care systems in sub-Saharan Africa are either non-existent or are grossly inadequate to deal with this burgeoning double burden of disease and its myriad repercussionsReference Kitange, Machibya, Black, Mtasiwa, Masuki and Whiting13–Reference Unwin, Setel, Rashid, Mugusi, Mbanya and Kitange15.

The NCD epidemics currently sweeping sub-Saharan Africa have been directly attributed to the nutrition transition, whereby traditional foods and food habits have been progressively replaced by the globalised food system of the multinational corporationsReference Popkin10, Reference Popkin16, Reference Popkin17. This transition in dietary practices has resulted in the increased consumption of refined flour, cheap vegetable fats, refined sugars and food additives such as monosodium glutamateReference Voster, Bourne, Venter and Oosthuizen18, all of which are known to hasten the development of the major NCDs (obesity, diabetes, CVD)19. In stark contrast, we have recently presented evidence that the traditional foods of East Africa, including a broad range of indigenous cereals, roots, tubers, fruits and vegetables, spices, animal fats, fish and wild bush meats, are associated with myriad health benefits, including protection against various NCDsReference Raschke, Oltersdorf, Elmadfa, Wahlqvist, Cheema and Kouris-Blazos20. Thus, while the globalised food culture exerts a pathogenic effectReference Poulter, Khaw, Hopwood, Mugambi, Peart and Rose21–Reference Poulter, Khaw, Hopwood, Mugambi, Peart and Rose23 and traditional foods exert a protective effectReference Pauletto, Puato, Caroli, Casiglia, Munhambo and Cazzolato24–Reference Liu and Li31, it is the globalised food culture which continues to be propagated and adopted.

Development of the globalised food system, a system inherently connected to the global epidemics of NCDs, is rooted in the creation of policies and institutions which govern the production, trade, distribution and marketing of foodReference Lang32, Reference Hawkes33. Currently, a handful of multinational corporations control this system and, as such, exert direct control over the creation of NCD epidemics. Control of the population by the transnational corporations is exerted by a scarcity-through-abundance philosophy. These corporations are as such committed to the eradication of quality whole foods (scarcity) and the widespread dissemination of insidious, low-quality processed foods (abundance)Reference Raschke, Oltersdorf, Elmadfa, Wahlqvist, Cheema and Kouris-Blazos20. This corporate philosophy is summarised succinctly by Ray Kroc, the founder of McDonald’s, as cited in Eric Schlosser’s Fast-Food Nation Reference Schlosser34:

We have found out…that we cannot trust some people who are nonconformists… We will make conformists out of them… The organization cannot trust the individual; the individual must trust the organization.

Throughout history, external influences have brought about changes in African food cultureReference Eaton and Konner35–Reference Oniang’o and Komokoti37. In centuries past, the overall objective of the colonial powers was to subjugate the population through the seizure of arable land and control of the food system. Control of the population via the globalised food system today continues to be inherent to the desires of the New World Order, an agenda for global hegemony driven by the multinational corporations, their political allies and the global elite, as exposed by innumerable authorsReference Cannon3, Reference Chossudovsky4, Reference Icke38. Indeed, the globalised food system has recently been described as a weapon of controlReference Action39. Susan GeorgeReference George40 revealed this perspective over 30 years ago, when she stated:

This is what food has become: a source of profits, a tool of economic and political control; a means of ensuring effective dominance over the world at large and especially over the ‘wretched of the earth’.

While the simplification of African food culture may be most apparent today, the nutrition transition has actually occurred over the past 400 yearsReference Schlosser34–Reference Oniang’o and Komokoti37, 41. At present, there is an imperative need to investigate and disseminate information related to the factors historically responsible for the nutrition transition in sub-Saharan Africa. Such inquiry is required to fully comprehend current NCD epidemics, and improve the health status of the marginalised indigenous people. The abatement of NCD epidemics could potentially be facilitated by the resurrection of the ancient, indigenous knowledge pertaining to traditional foods and food habitsReference Raschke, Oltersdorf, Elmadfa, Wahlqvist, Cheema and Kouris-Blazos20.

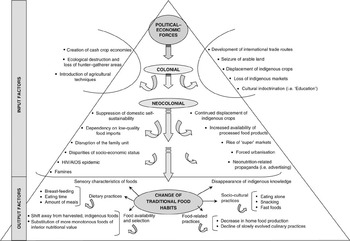

The purpose of the present article is to discuss factors which have underpinned the nutrition transition in the countries of East Africa, including Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania, from early colonisation to the current, oppressive political–economic structure. A conceptual framework which outlines the colonial and neocolonial contributors to the eradication of traditional food habits throughout East Africa over the past few centuries is provided in Fig. 1 and is discussed herein.

Fig. 1 Colonial and neocolonial factors related to the eradication of traditional food habits in East Africa

Ancient and traditional food habits of East Africa

Approximately 5000 years ago much of East Africa was occupied by hunter–gatherers commonly called the ndorobo 41. These ancestors primarily consumed wild game, wild birds and eggs, wild fish, wild insects (e.g. grasshoppers, ants, caterpillars, termites) and wild plant foods (e.g. fruits, nuts, tubers, honey)41. The ndorobo were later assimilated by migrants and lost much of their cultural identity, which included the loss of these food habits41. Interestingly, Eaton and KonnerReference Eaton and Konner35, who have advanced awareness of dietary changes over several millennia in Africa, have concluded that the human diet was far superior with the hunting and gathering subsistence of palaeolithic times compared with the current globalised food system.

Agriculture in East Africa was pioneered by the Cushitic speakers arriving from the Ethiopian highlands and other cultivators arriving from the south, west (Bantu), and north-west (Nilotes) approximately 1000 years ago. During the initial stages of the agricultural age, nutrient-dense, indigenous grains and foods from pastured animals (e.g. milk, lard, offal and blood) became incorporated into the local diets41. The earliest food crops of agriculturalists in East Africa included sorghum, finger and pearl millets, hyacinth (lablab) beans, bambara groundnuts, bottle gourds, cowpeas and yams41–Reference Gura43. These staple foods are associated with many health benefitsReference Raschke, Oltersdorf, Elmadfa, Wahlqvist, Cheema and Kouris-Blazos20. Cultivated and wild vegetables, especially wild green leaves including amaranth, black nightshade and red sorrel, as well as various other wild plant foods were important ingredients for sauces accompanying the carbohydrate staples41. The traditional East African diet was also based on high amounts of fat-soluble vitamins which enabled proper physical development, low susceptibility to chronic diseases, high tolerance to infectious diseases and an absence of tooth decay according to the investigations of Dr Weston A PriceReference Price44.

Colonisation and the nutrition transition

Development of international trade routes

Food habits in East Africa began to shift dramatically in the 1400 s with the development of coastal trading towns, the creation of international trade routesReference Coupland45 and the onset of European colonial occupationReference Dugian, Gann and Turner2, Reference Eaton and Konner3,5. Two distinct events in relation to international trade had a profound influence on the food habits of the East African population. The first was the discovery and use of the sea route to India and South-East Asia in the late 15th and early 16th century, and the second was the development of the international Columbian Exchange system which occurred with the ‘discovery’ of the Americas by Christopher Columbus in 1492Reference Coupland45.

Through trade with Asia, East African farmers acquired a number of crops, such as plantain, banana, cocoyam, coconut and sugar cane, which were rapidly assimilated into the local diets41. Columbian Exchange also led to the introduction of staple crops from the Americas, including, most notably, maize, rice, peanut (groundnut), tomato, sweet potato, English potato, kidney bean, pumpkin, cassava (manioc), European cabbage and kale (Sumuka wiki)41, Reference Smith46. These particular foods proved to be ecologically sustainable and thus rapidly altered and diversified the dietary intake of East Africans. Use of these introduced foods became widespread throughout the colonial period41, and the indigenous people commonly replaced indigenous crops with overseas varieties. Some of these introduced staple crops threatened to replace robust, nutrient-dense, indigenous crops including varieties of millet and sorghum spp.Reference O’Ktingati, Temu, Kessy, Mosha and Baidu-Forso47.

Seizure of arable land

Land pressures in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda during colonisation fundamentally arose from colonial policies which enabled European settlers to seize control of so-called ‘empty lands’Reference Ogutu48, Reference Caldwell and Boahen49. These empty lands were in fact some of the best arable lands in East AfricaReference Ogutu48, Reference Caldwell and Boahen49. Driven from their lands, and denied equitable access to the natural resources, indigenous farmers were typically forced to congregate on small plots of marginal lands, which could not support agricultureReference Ogutu48–Reference Anderson50. The seizure of arable lands also resulted in reduced livestock ownership among the indigenous peopleReference Anderson50. This loss of livestock drastically reduced intake of animal proteinReference Anderson50–Reference Bohdal, Gibbs and Simmons52. Inadequate animal protein intake, resulting in a high prevalence of protein–energy malnutrition among the local, indigenous people of East Africa, has been well documented from the 1960sReference Raschke, Oltersdorf, Elmadfa, Wahlqvist, Cheema and Kouris-Blazos53 to the present dayReference Ramakrishnan54.

Creation of cash-crop economies

By the end of the 19th century, the colonial powers (i.e. Portugal, Great Britain and Germany) in East Africa aimed to advance a trading system which predominantly served the European elite and their industriesReference Winter-Nelson55. Primarily, it was the imperial power of Great Britain that exploited the production and export of East African-grown staple crops and other valuable commodities in order to consolidate their powerReference Cannon3. This exploitation of the 1950s resulted in the creation of ‘cash-crop economies’Reference Read56. These cash-crop economies were primarily based on the production of coffee, copra, cotton, sesame, peanuts and sugar for the Western markets (i.e. Europe, North America and Australia) and persist todayReference Ayittey6, Reference Chopra and Darnton-Hill57. From the outset, rural communities were encouraged by the British to grow food crops for export in order to earn money to ‘improve their standards of living’ under a new economic systemReference Read56. As such, domestic food production became neglected by East Africans now forced to pay taxesReference Turshen58.

The onset of cash-crop farming dramatically reduced the domestic availability of robust, nutrient-dense, traditional crops, including sorghum spp., pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum), finger millet (Eleusine corocana), cowpea (Vigna unguiculata), bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea) and pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan), all of which are drought-tolerant to a considerable extentReference Gura43, Reference Harlan, Janick and Simon59, Reference Abegaz, Demissew and Baidu-Forson60. The introduction of foods of ‘modern commerce’, such as refined sugar, refined wheat and maize flour, canned food and condensed milk, occurred rapidlyReference Price44 as there was little respect shown by the colonial powers towards the nutritional and cultural benefits of indigenous and traditional African foodsReference Allen61–Reference Latham63.

Ecological destruction

Diverse forest ecosystems were rapidly cleared for land needed to support cash-crop farmingReference Read56. This ecological degradation eliminated many indigenous food trees and gathered foods from the dietReference Tabuti, Dhillion and Lye64. Several indigenous fruit species and wild food plants diminished in the traditional diets, affecting the taste and nutrient content of common dishesReference Gura43, 65, Reference Okigbo66. Utilisation of wild bush meat decreased, given fewer areas for huntingReference Read56.

Food habits were also drastically altered with the introduction of new agricultural techniques assimilated for the production of cash cropsReference Welch and Graham67. These techniques promoted the adoption of higher-yielding monocultures of maize, rice and wheat. Monocultures displaced traditional African food crops grown with traditional cultivation techniques including ‘shifting cultivation’ and ‘intercropping’, which historically evolved to suit the local agricultural conditionsReference Gura43, Reference Shiva68. Traditional cultivation patterns protected the soil, minimised weeds, provided communities with a variety of food, and reduced the risk of crop failure, pests and plant diseases, whereas monocultures provide none of these benefitsReference Gura43.

The systematic loss of indigenous crop varieties has reduced biodiversity and hastened dietary simplificationReference Okigbo66, Reference Platt79. The shift towards monocultures and reduced dietary diversity has also resulted in a loss of knowledge of ancient agricultural practicesReference Kuhnlein and Receveur70. Overall, the introduction of new agricultural methods has benefited the Western powers economically, but has caused incredible ecological devastation and human suffering throughout East AfricaReference Tudge71. Numerous plant and animal species are no longer available because habitats have been irreparably destroyed, cleared for commercial agriculture. Traditional foods such as the wild Dioscorea spp., which have historically played an important role in sustaining the population during periods of drought and famine, are now on the verge of extinction due to the ecological damage incurredReference Asfaw and Tadesse72.

Loss of indigenous markets

The marketplace was the heart of pre-colonial African societyReference Ayittey6. Markets were not only the centre of economic activity, but also the centre of political, social, judicial and communication activitiesReference Ayittey6. In East Africa, studies by GulliverReference Gulliver, Bohannan and Dalton73 have revealed that the indigenous markets were extremely important to the Arusha people because the markets provided them their main opportunity for personal contact with the Maasai in the conscious effort to learn and imitate all they could of the Maasai cultureReference Gulliver, Bohannan and Dalton73.

Women in Africa have always played a prominent role in market activities and tradeReference Hodder, Bohannan and Dalton74. For example, local farm produce was almost invariably marketed and sold by womenReference Hodder, Bohannan and Dalton74. Today, female traders and some indigenous economic systems still exist. However, when Africa was colonised, the colonialists began to control indigenous economic activities to their advantageReference Ayittey6. Attempts to reduce or destroy these local market operations resulted in the decline of female participation in market activity, sending shockwaves through the larger family unit, and as such the entire food systemReference Skinner, Bohannan and Dalton75. Further, loss of the indigenous marketplace has resulted in reduced access to quality whole food options and reduced knowledge of traditional food habitsReference Skinner, Bohannan and Dalton75.

Cultural indoctrination (i.e. ‘education’)

Indoctrination has negatively impacted traditional food habits in East Africa since early colonisation. The primary vectors for the cultural indoctrination were the mission schools, boarding schools and public health programmes responsible for educating the youthReference Kuhnlein and Receveur70. These methods of ‘education’ have uniformly reduced knowledge related to the cultivation and preparation of traditional and wild foodsReference Culwick76. Traditional knowledge has been devalued as the education of children has shifted away from the tribal elders, the primary educators in the past, to the imperial powers via the church and schoolReference Tabuti, Dhillion and Lye64, Reference Cattell77. ‘Education’ encouraged ‘sophistication’, which included a repugnance for traditional foods and ancient methods of food preparationReference Culwick76, explaining, at least partially, why nutritious, indigenous foods are drastically underutilised and undervalued todayReference Okigbo66, Reference Farnsworth78–81.

Neocolonisation and the nutrition transition

Colonial influences on Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda abated during the late 1950s to early 1960s when these countries reportedly gained independence. The 1960s and 1970s were marked by relative economic growth; however, economic deterioration soon ensued as these developing countries were unable to fulfil their financial obligations to the banks and official development agencies of the industrialised worldReference Ayittey6, Reference Labonte, Schrecker, Sanders, Meeus, Cushon and Torgerson82. Hence, a need for economic policy reforms was created. The implementation of privatisation and cost recovery initiatives (structural adjustment) by the international financial institutions, primarily the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), from the 1970s through to the present day, has adversely affected the food habits of the East African population, contributing markedly to the deterioration of health status and the creation of NCD epidemicsReference Labonte, Schrecker, Sanders, Meeus, Cushon and Torgerson82–Reference Chossudovsky84.

In the 1980s, one of the core objectives of debt rescheduling in the form of structural adjustment programmes and trade liberalisation was to ‘make domestic agriculture more market-oriented’Reference Milward85, 86. Trade policy reforms accelerated in the 1990s as the East African countries liberalised their economiesReference Chossudovsky4, Reference Ayittey6. Invariably, however, economic policy shifts in East Africa over the past 20 to 30 years have resulted in the increased centralisation of power to the benefit of the multinational corporationsReference Pelto and Pelto87, Reference Lang, Shetty and McPherson88. The corruption underlying the World Bank and IMF programmes and the inherent connection between these agencies and the New World Order agenda has been effectively exposed ad infinitum Reference Ayittey6, Reference Icke38, Reference Labonte, Schrecker, Sanders, Meeus, Cushon and Torgerson82, Reference Chossudovsky84, Reference Pilger89, Reference Klein90.

The Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) pledged to improve tariffs, export subsidies and domestic agricultural support for struggling African countriesReference Chossudovsky4, 91. However, once again, these measures led to restructuring of the national economy which increased export exploitation by consolidating power among a few multinational corporationsReference Chossudovsky4, Reference Lugalla92. As such, trade policy reforms have enabled greater control of corporations over households through the direct and indirect control of employment opportunities, earnings, and daily expenditures related to subsistence living (i.e. food, clothing, shelter)Reference Lugalla92–Reference Pinstrup-Andersen94.

Delocalisation of food production, food distribution and food marketing has redistributed power over food systems from the local economy to a few multinational corporationsReference Schlosser34, Reference Lang and Heasman95. In the case of wheat, a handful of companies dominated the world market several decades agoReference Morgan96. However, economic power has become increasingly centralised and the world grain market is now dominated by one company, CargillReference Kneen97. Four multinational corporations now own approximately 45% of all patents for staple crops such as rice, maize, wheat and potatoes98. This rapid centralisation of power has resulted in a globalised food system and commercially driven changes in food habits and tastesReference Stitt, Jepson, Paulson-Box, Prisk, Koehler, Feichtinger, Barlosius and Dowler99, and is inherently implicated in the development of NCD epidemics in East Africa and, indeed, worldwide.

Suppression of domestic self-sustainability

The monopolisation of arable land in East Africa has benefited the transnational corporations and their Western consumersReference Cannon3, Reference Lang32. Indigenous African farmers, who would normally rely on this arable land for growing food crops for the local marketplace and local consumers, continue to be displaced or are employed by the corporations for extremely low wagesReference Hewitt de Alcantara69, Reference Tudge71. Instead of growing basic food crops for local people, the indigenous farmers are being encouraged to focus on ‘high-value’ agricultural products such as fresh flowers and exotic fruits for exportReference Chopra and Darnton-Hill57.

Dependence on low-quality staple food imports

With all hopes of self-sustainability virtually obliterated by trade policy reforms, East Africans have been increasingly forced to rely on low-quality food imports. In 2001, Africa accounted for 18% of world food imports, up 10% from 1985100. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations91, food imports have increased in East Africa due to a decline in domestic agricultural investmentReference Ayittey6.

Wheat, which currently dominates world food trade101, is currently exported from just five countries: the USA, Canada, Australia, Argentina and France101. Increased reliance on imported wheat has been documented in East Africa101. Wheat importation in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda has increased markedly since the early 1990s (Fig. 2)102. Wheat is nutritionally inferior to indigenous, drought-resistant alternatives, including various millets and sorghum spp.Reference Raschke, Oltersdorf, Elmadfa, Wahlqvist, Cheema and Kouris-Blazos20. Increased reliance on imported wheat has been attributed to domestic food insecurity, which can in turn be attributed to trade policy reformsReference Lang32, Reference Haan, Farmer and Wheeler103.

Fig. 2 Wheat importation (metric tonnes) in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda from 1962 to 2004102

With the exception of a downward trend from the mid-1990s to 2001, perhaps due to the fluctuation of oil prices and the loss of subsidies, the importation of hydrogenated vegetable fats has also increased in East Africa over the past decade and a half (Fig. 3)Reference Visvanathan104. Elevated intake of trans-fatty acids (all types of isomers) has been shown to increase serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and decrease high-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentrationsReference Katan105, and as such increase the risk of CVDReference Aro106, Reference Oomen, Ocké, Feskens, van Erp-Baart, Kok and Kromhout107. The increased availability and affordability of industrial, hydrogenated oils vs. traditional alternatives (e.g. oil of shea butter nut and lard) has contributed markedly to dietary simplification and the development of NCD epidemics in East AfricaReference Popkin11, Reference Bourne, Lambert and Steyn12, Reference Njelekela, Ikeda, Mtabaji and Yamori108.

Fig. 3 Importation of hydrogenated oils (metric tonnes) in Uganda from 1994 to 2004Reference Visvanathan104

Continued displacement of indigenous crops

Recent macroeconomic trade policy reforms have further displaced indigenous crops91. In Kenya and Uganda, dietary patterns have shifted away from the use of indigenous crops (e.g. millets, sorghum spp., pulses and starchy roots) (Figs 4 and 5)102 to a greater consumption of introduced staple foods, including wheat, rice and hydrogenated vegetable fats101.

Fig. 4 Traditional crops available for consumption in Kenya from 1961 to 2003. Source: Food balance data from FAOSTAT database102

Fig. 5 Traditional crops available for consumption in Uganda from 1961 to 2003. Source: Food balance data from FAOSTAT database102

In Tanzania, the availability of sorghum spp. and millets has generally been maintained over the past 60 years (Fig. 6)102 due to their importance as drought-resistant, staple foods for various ethnic groups109. However, a decline in the availability of indigenous starchy roots and an increase in the availability of rice and maize have been observed since the early 1970s (Fig. 6)102. Although maize has become the most available staple food in Tanzania over the past 45 years (Fig. 6), its availability decreased slightly from the 1980s onwards109. This stagnation may have been due to reduced maize fertiliser subsidies, as well as adverse weather conditions109, 110. The increased availability of rice between 1970 and 2000 is due to an increase in the importation of this staple111.

Fig. 6 Introduced and traditional crops available for consumption in Tanzania from 1961 to 2003. Source: Food balance data from FAOSTAT database102

Increased availability of processed food products

International trade and the liberalisation of foreign direct investment under GATTReference Reardon and Swinnen112 has consolidated food systems for the multinational corporationsReference Shiva68, Reference Lang, Shetty and McPherson88, Reference Hawkes113, Reference Hawkes114. In 2001, 12 transnational food product manufacturers ranked among the top 100 list of foreign asset holders worldwide, double the number in 1990115, 116. From 1990 to 2002, the combined foreign assets of these companies increased from approximately $US 34 billion to $US 258 billion115, 116. During that same period, the foreign sales of these companies increased from approximately $US 89 billion to $US 234 billion115, 116. Multinational corporations, the primary control mechanism of the New World Order, fundamentally drive the integration of world markets and, as such, affect the indigenous and traditional food habits of developing countriesReference Hawkes33, Reference Maletnlema117, Reference Mazengo, Simell, Lukmanji, Shirima and Karvetti118. The displacement of indigenous and traditional foods is innate given an economic structure which favours these corporationsReference Cannon119.

The rise of ‘super’markets

Shoprite©, the largest supermarket retailer in Africa, has become a deeply entrenched aspect of East African cultureReference Weatherspoon and Reardon120, 121 and serves as a primary vector for the dissemination of low-quality, packaged food products of the multinational corporationsReference Neven and Reardon122. The transformation of food retail in Africa including the development and widespread propagation of supermarkets first occurred in South Africa, followed by Kenya during the mid-1990sReference Reardon, Timmer, Barrett and Berdegue123. In 2002, Kenya had approximately 206 supermarkets and 10 hypermarkets (which contain 10 times the floor space of a supermarket)124. Currently, supermarket expansion is occurring rapidly in Kenya, particularly into poorer demographic areas, and in secondary cities and townsReference Weatherspoon and Reardon120. Access to cheap convenience foods by way of supermarkets has reduced the prevalence of local markets and the availability of indigenous and traditional foodsReference Weatherspoon and Reardon120, Reference Reardon, Timmer, Barrett and Berdegue123. Tanzania and Uganda are currently in the early stages of supermarket developmentReference Weatherspoon and Reardon120.

Consequences of urbanisation

Economic pressures have resulted in mass migration from rural areas to urban centres in East Africa125. In Kenya the percentage of the population living in urban areas increased from 10% in 1970 to 30% in 1997125. In Tanzania and Uganda, the annual urban population growth rate was 7.4% and 5.9%, respectively, from 1980 to 1990 and 7.1% and 3.8%, respectively, from 1990 until 2000126. Several consequences related to rapid urbanisation have contributed to the nutrition transition in East Africa.

Urbanisation in East Africa has contributed to a shift away from traditional high-fibre, home-cooked foods to the consumption of pre-prepared, packaged and processed ready-to-eat foodsReference van’t Riet, den Hartog, Hooftman, Foeken and van Staveren127–Reference Nasinyama129. The elevated consumption of trans fats, refined sugars, refined flours and preservatives, and low intake of dietary fibre and vital micronutrients, as a result of these new foods, has resulted in adverse health effects in the urban East African populationReference Njelekela, Ikeda, Mtabaji and Yamori108, Reference Njelekela, Kuga, Nara, Ntogwisangu, Masesa and Mashalla130–Reference Edwards, Unwin, Mugusi, Whiting, Rashid and Kissima132. Recent evidence from the urban centre of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania revealed a positive relationship between the consumption of a Westernised (globalised) diet and the prevalence of NCDs, including risk factors which comprise the metabolic syndromeReference Njelekela, Ikeda, Mtabaji and Yamori108, 133–Reference Mosha137. The urban East African population is constantly confronted with the widespread availability of packaged food productsReference Lang32, Reference Mazengo, Simell, Lukmanji, Shirima and Karvetti118, Reference Cannon119, Reference Chopra, Galbraith and Darnton-Hill138. The shift in preferences away from traditional, indigenous foods and commodities to diets based on Westernised consumption patterns has been encouraged by governments and their corporate allies, particularly in the last five years with the rapid expansion of fast-food restaurants chains which are catering to the East Africa urban centres, and even to some of the smaller rural townsReference Weatherspoon and Reardon120, Reference Regmi and Gehlar139, 140. Many people residing in urban areas are unaware of the health benefits of indigenous African foodsReference O’Ktingati, Temu, Kessy, Mosha and Baidu-Forso47, Reference Kinabo, Mnkeni, Nyaruhucha, Msuya, Haug and Ishengoma141. Thus, the knowledge of traditional food habits in the urban centres has waned from one generation to the nextReference Kuhnlein and Receveur70. The extent to which globalised dietary patterns and food habits are adopted in rural towns has not been effectively investigated to date; however, recent evidence suggests that Westernised meal patterns are in fact infiltrating the rural areas of TanzaniaReference Mazengo, Simell, Lukmanji, Shirima and Karvetti118. Urban residences in East Africa are generally characterised by small living spaces, poorly equipped kitchens or outdoor cooking spaces, and poor access to natural fuel sources and clean water, which all contribute to a disruption of traditional dietary practicesReference van’t Riet, den Hartog and van Staveren142, Reference Chandler and Wane143. As such, urban consumers become more reliant on highly processed, non-home-prepared foodsReference Maletnlema117, Reference van’t Riet, den Hartog and van Staveren142, 144. Street foods and foods from kiosks are the major sources of non-home-prepared foods in the poor urban areas in East AfricaReference van’t Riet, den Hartog, Hooftman, Foeken and van Staveren127–Reference Nasinyama129. The fact that street foods are inexpensive, time-saving and convenient are the main purchasing incentives among poorer, urban East AfricansReference Nasinyama129, Reference van’t Riet, den Hartog, Mwangi, Mwadime, Foeken and van Staveren145, 146. Often street foods are prepared using the least expensive ingredients, including refined flour, maize and hydrogenated oils. These foods contain few essential nutrients, and are high in refined sugars. In addition, problems of hygiene and food safety are bound to arise in the unsanitary conditions of the shanty towns and slums where the poorest groups live and consume street foods144. The consumption of street foods may also be coupled with adverse eating patterns, including such behaviours as eating alone and frequent snackingReference van’t Riet, den Hartog, Hooftman, Foeken and van Staveren127.

Disruption of the family unit

Macroeconomic policy reforms in East Africa have disrupted the family unit by placing greater demands on women. Increasingly, women have been forced to enter the urban labour market to improve family survivability. This has included spending longer hours on the job to meet basic needsReference Ayittey6. Demands on women living in the rural setting have also increased recently, particularly with the continued migration of rural men seeking employment to urban centresReference Kavishe and Mushi147. Rural women in East Africa have been forced to work longer hours to meet cash-crop demandsReference Lugalla92.

The absence of women from the family unit has increasingly displaced traditional foods which are time-consuming to prepare compared with easily prepared import grains and high-calorie/low-nutrient fast foods and street foodsReference Lang32, Reference Fouéré, Maire, Delpeuch, Martin-Prével, Tchibindat and Adoua-Oyila148. Kennedy and ReardonReference Kennedy and Reardon131 have asserted that increased labour demand on women is the primary factor responsible for the increased consumption of pre-packaged bread in urban Kenya.

With women entering the economic employment sector, the breast-feeding of infants has declinedReference Kavishe and Mushi149. A study in urban Morogo, Tanzania, revealed unusually shortened breast-feeding periods150. Reduced breast-feeding periods are associated with poorer nutritional status and increased susceptibility to diseases, particularly diarrhoea and measles, among infants and childrenReference Kavishe and Mushi149.

Disparities of socio-economic status

GrayReference Gray151, among many others, has suggested that with economic liberalisation differences in incomes between various segments of society have increased dramatically, causing marked inequities in food access. Dietary choices are dependent on the socio-economic status of the familyReference Read56, and lower-income families have less access to higher-quality whole foods. The cost of traditional staple foods in urban areas is generally higher than the cost of processed foodstuffsReference Ruel, Haddad and Garrett152. This has generally led to the increased consumption of easy-to-prepare foods and snacks among the urban poor, resulting in dietary deficienciesReference van’t Riet, den Hartog, Hooftman, Foeken and van Staveren127, Reference Nasinyama129, Reference Kavishe and Mushi153. Several studies have revealed higher consumption of street foods among urban dwellers of lower socio-economic status in East AfricaReference Nasinyama129, Reference van’t Riet, den Hartog, Mwangi, Mwadime, Foeken and van Staveren145.

Nutrition-related propaganda (i.e. advertising)

Today, the mass marketing of packaged food products is ubiquitous and the negative effects of such advertising campaigns have been well documented154–Reference Dalmeny, Hanna and Lobstein156. Perhaps the most notorious example of such propaganda was the mass marketing and sale of artificial milk powders for infants and children by NestléReference MacLennan and Zhang30. The use of these ‘milk’ formulas reduced the extent of breast-feeding and resulted in deaths from intestinal infections, diarrhoea and dehydration due to a contaminated water supplyReference Akre157.

Marketing strategies have often deliberately appealed to existing cultural viewpointsReference Hawkes113, Reference Lang158. Clear contradictions and bizarre connections abound in these advertising campaigns. For example, McDonald’s uses its resources and popularity to promote the United Nations Children’s Fund and its mission to eradicate malnutrition in childrenReference Dyer159, perhaps insinuating that children should be ‘nourished back to health’ with McDonald’s food.

Children in particular have become the primary targets of international marketing campaigns promoting packaged foodsReference James160. Advertising is now well recognised as a significant contributor to the nutrition transition and the general acceptance of a globalised food cultureReference Lang158. Brand marketing has been facilitated by the dramatic improvement in packaged food distribution within and between countriesReference Lang32. It is rather ironic yet unsurprising that advances in food distribution systems (i.e. transportation) have benefited the multinational corporations, yet have not been effectively used to facilitate the widespread distribution of quality whole foods to nourish the needy.

Engineering of famines

While climatic variables play a role in triggering famines, famines in the age of globalisation are also markedly influenced by the neocolonial (political–economic) forces of the New World OrderReference Davis5, Reference Sen161. Sectoral adjustment under the IMF and World Bank undermines food security and reinforces a developing country’s dependency on the world market. The engineering of famines through the economic policies of these institutions has been superbly exposed by ChossudovskyReference Chossudovsky162 in the Globalization of Poverty and the New World Order.

Consequences of disease epidemics

In addition to NCDs, HIV/AIDS, malnutrition and infectious disease epidemics continue to escalate in East Africa163. Together, or in isolation, these epidemics exert a devastating effect on population health, which drastically alters work and earning capacity and, as such, food purchasing power and food habits. The morbidity and mortality associated with AIDS has been shown to affect farm labouring in the rural setting164, Reference Barnett and Rugalema165. Infectious and NCD epidemics also markedly increase expenditures for medical treatments, transportation and funerals, resulting in reduced affordability of quality foods166–Reference de Waal and Tumushabe169.

Discussion

A nutrition transition has been occurring in East Africa over the past 400 years and has been underpinned by both overt and covert methods of control, from colonisation to the current, oppressive political–economic structure. Uniformly, colonisation and neocolonisation have excised the ancient, indigenous knowledge, destroyed the environment, suppressed domestic self-sustainability, prevented economic independence, forced rapid urbanisation, destroyed the family unit, and introduced a globalised food system. This globalised food system, advanced through the economic reforms of the World Bank and IMF and now controlled by a handful of multinational corporations, has been directly implicated in the recent upsurge of NCDs throughout East Africa, including the countries of Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania.

It is essential that knowledge of the contributing factors related to the disappearance of traditional foods and foods habits in East Africa become widely acknowledged, accepted and understood. Greater efforts must continue to be directed towards exposing the control mechanisms (i.e. multinational corporations) of the New World Order, disseminating knowledge, and proposing effective solutions to the nutrition transition. Such efforts might very well be underway today.

Awareness of the health-related benefits of traditional foods and food habits in East Africa is improving due in part to recent scientific investigations and new online information sourcesReference Raschke, Oltersdorf, Elmadfa, Wahlqvist, Cheema and Kouris-Blazos20, Reference Raschke, Oltersdorf, Elmadfa, Wahlqvist, Kouris-Blazos and Cheema170–174. Adoption of these traditional foods and food habits along with the underlying ancient knowledge is likely to hold the key to overcoming the globalised food system and current NCD epidemics. Grass-roots efforts may be underway at Bioversity International (formerly the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute)175 to empower local farmers and producers, and improve the availability, conservation and use of underutilised and neglected species. Furthermore, IndigenoVeg is currently promoting the production of indigenous vegetable varieties in urban and peri-urban areas of Africa176.

The dissemination of traditional knowledge and grass-roots campaigns must continue. Importantly, such efforts must elude being hijacked by the very forces they are intending to thwart, including individuals and organisations intending to profiteer from the patenting of particular crops and their genes. Ultimately, it is the individual, the family unit and the local community that must unite to reclaim their birthright to grow and consume their own local whole foods according to their own traditional practices. Such concerted efforts are required to circumvent the New World Order and their multinational corporations which currently control the global food system.

In summary, it is imperative that greater efforts be directed towards exposing the colonial and neocolonial forces which have undermined food security in East Africa and throughout the rest of the world. Heightened awareness of these forces is essential for proposing genuine, holistic solutions to the nutrition transition and related NCD epidemics in East Africa and indeed worldwide.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Ms Geeta Cheema, MPA, and Ms Preme Kaur Cheema, MA, for their valuable contributions towards the preparation of this manuscript. We also wish to thank the many influential authors who have served, and continue to serve, as guiding lights in our research. Many of these authors have been cited in this article.