Rapid weight gain during infancy, defined as an increase in weight-for-age Z-score of >0·67 SD, has been associated with an increased risk for obesity in childhood and beyond(Reference Jebeile, Kelly and O’Malley1–Reference Kwon, Janz and Letuchy4). In addition to prenatal factors, such as maternal overweight/obesity and excess weight gain during pregnancy, the rate of weight gain during infancy is influenced by feeding practices(Reference Matthews, Wei and Cunningham5–Reference Meek and Noble7). The Dietary Guidelines for Americans added infant feeding recommendations in the 2020–2025 revision, including exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months and continuing it along with complementary foods for 1 year or longer(8).

Breastfeeding is a biologically active delivery system with interacting components that provide multiple benefits to infants, in addition to nutrition(Reference Christian, Smith and Lee9). Breastfeeding is associated with a lower likelihood of respiratory infections, ear infections, severe diarrhoea, sudden infant death syndrome and improved neurodevelopment(8). The relation between breastfeeding and childhood obesity has been inconclusive. A recent meta-analysis of 153 studies reported that breastfeeding is associated with a 30 % reduction in children’s obesity risk after controlling for socioeconomic status, suggesting that breastfeeding may be associated with normal growth during infancy(Reference Horta, Rollins and Dias10). Studies have found that irrespective of intensity (exclusive breastfeeding v. mixed breastfeeding and formula), duration of breastfeeding from 4 to 6 months is associated with reduced risk for rapid weight gain or accelerated growth by half(Reference Zheng, Hesketh and Vuillermin11–Reference Wood, Witt and Skinner13). However, there is a lack of information on associations between breastfeeding continuation in the complementary feeding phase of post 6 months and growth trajectory among infants from racially and ethnically diverse backgrounds(Reference Min, Goodale and Xue14).

Latino and African American children are at increased risk for early rapid weight gain, compared to non-Latino White children(Reference Taveras, Gillman and Kleinman15,Reference Isong, Rao and Bind16) . For instance, Taveras et al. found that the rate of overweight/obesity among Latino and African American school-age children was almost double than among non-Latino White children, and the higher obesity in turn was associated with a greater likelihood of rapid weight gain during infancy(Reference Taveras, Gillman and Kleinman15). Similarly, in a longitudinal assessment, higher weight gain among African American v. White infants in the first 9 months accounted for 70 % of the difference in obesity at 5 years of age(Reference Isong, Rao and Bind16). Health disparities, including rapid weight gain and obesity, are also associated with other social risk factors, including living below the poverty line and food insecurity(Reference Benjamin-Neelon, Allen and Neelon17,Reference Frongillo18) . In alignment with the call for science and strategies to address inequities in the September 2022 House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health(19), the study objectives were to describe breastfeeding rates from early to late infancy and to examine associations between breastfeeding duration and infant growth, including rapid weight gain, among infants from low-income, racially and ethnically diverse backgrounds.

Methods

The study was approved by the University of North Carolina at Greensboro’s Institutional Review Board. In total 276 mother-infant dyads were recruited between August 2019 and November 2021 in the waiting area of a pediatric clinic that serves primarily Medicaid recipients from diverse racial and ethnic families. The study inclusion criteria were (1) singleton birth; (2) full-term (≥ 37 weeks); (3) maternal age ≥ 18 years; and (4) infant age < 2 months. Participation was restricted to English or Spanish speakers, as translator services for languages such as Swahili, Arabic and Karen were unavailable. Infants with health issues, such as cleft palate or congenital abnormalities that might affect breastfeeding were not included.

Trained research assistants approached mothers with young infants and explained the study in detail, i.e. participation involved retrieval of anthropometrics from infant’s health records and interviews on sociodemographic, breastfeeding and related infant feeding practices at 2, 4, 6, 9 and 12 months of infant’s age. Mothers who expressed interest, met eligibility criteria and agreed to participate were asked to provide written informed consent for themselves and their infant. Mothers were also asked for permission to access infants’ anthropometric information from clinic records by signing the Health Insurance and Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA) form. About 80 % of mothers who met eligibility criteria signed the consent and HIPPA forms.

To estimate the necessary sample size, Monte Carlo simulations of the proposed multilevel growth models were conducted using potential effect size estimates (0·2 to 0·5). Standards for minimum coverage were set at 95 %, estimated bias at less than 5 % and power ≥ 0·8, with attrition rates ranging from 10–20 %. For fixed effects of time and breastfeeding status as low as 0·25, a minimum sample estimated was 200 mother-infant dyads for a power of 0·99 to 0·88. With the clinic’s support, recruitment continued beyond the minimum sample target.

The interviews were conducted by research assistants who were fluent in English and/or Spanish and trained in interviewing skills, study-specific questions and data collection procedures. Infants’ weight and length measurements taken by trained pediatric nurses were retrieved from clinic records. Participants received a grocery gift card at each interview. Before the COVID-19 restrictions in March 2020, all 2-month interviews were conducted in-person at the pediatric clinic, with follow-up interviews conducted either in-person or by phone, depending on participant preference. Beginning March 2020, all interviews were conducted over the phone. To minimise bias and ensure that information was collected in a standardised manner, the principal investigator met with the team weekly to ensure that they were following the protocol and quarterly conducted quality checks, including data review and observations of each research assistant’s interviews.

Measures

During the interview, information on sociodemographic and breastfeeding status was collected. The interview window was set at +/- 10 days in reference to infant’s age (2, 4, 6, 9 and 12 months of age).

Sociodemographic data

During the initial interview at 2 months, mothers reported their race, ethnicity, age, education level, marital status, current body weight and height, and participation in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. We used their reported weight and height to calculate BMI.

Breastfeeding status

Questions from the Infant Feeding Practices Study II, sponsored by the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, were used to determine breastfeeding status at each interview(Reference Fein, Labiner-Wolfe and Shealy20). Upon confirming breastfeeding initiation, we asked the following question at the 2-, 4- and 6-month interviews, i.e. ‘Are you currently breastfeeding or feeding your baby pumped milk?’ Upon confirmation, we clarified whether the mother was exclusively or partially feeding breast milk.

At the 9- and 12-month interviews, we asked the breastfeeding question only if breastfeeding was reported in the previous interview. If the participant answered ‘no’ to the question about current breastfeeding, we asked ‘How old was your baby when you completely stopped breastfeeding and/or stopped giving pumped milk?’ The responses to these questions, along with the interview date and infant’s date of birth, were used to calculate the duration of breastfeeding. The interviews were conducted using the online data capture tool REDCap hosted at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

Anthropometric data

Infants’ weight and length, measured at well-child visits, were retrieved from clinic records. The pediatric nurses had participated in professional trainings on abnormal parameters for weight in children and limitations associated with weighing devices. After checking the anthropometric data for outliers, inaccuracies or questionable information, fifteen cases were dropped. Five additional participants were dropped due to missing more than two measurements and/or interviews. This resulted in the analysis sample size of 256 (92 %) of the 276 recruited mother-infant dyads.

After verification and quality checks, anthropometric data were used to calculate weight-for-length Z-scores based on the age- and sex-specific WHO parameters using the following equation(21): Z = ((Weight/M)L – 1)/(L * S).

Rapid weight gain was calculated as a change of > 0·67 SD in the weight-for-age Z-score between 2 and 12 months of age(Reference Monteiro and Victora22).

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted using R version 4.2.1(23). Descriptive statistics were used to examine sociodemographic variables and breastfeeding rates at each time point. Breastfeeding duration was dummy coded into 0–2 months, 3–6 months and 6+ months (reference group); these categories were used to examine differences in weight-for-length trajectory Z-scores and the risk for rapid weight gain from ages 2 to 12 months using multilevel growth modeling. Infant age was centred at 2 months; intercepts represented the predicted mean weight-for-length Z-score at the hypothetical age at first contact. Based on the literature, sociodemographic variables associated with infant growth were controlled in the models, including infant sex, parity, race, ethnicity, maternal BMI, education and type of delivery. Initial inspection of the data suggested that weight-for-length trajectories were nonlinear. Therefore, likelihood ratio tests were conducted to compare model fit among linear, quadratic and cubic growth models, controlling for breastfeeding duration. Once the most appropriate growth form was identified, other covariates and breastfeeding duration-by-age interactions were entered into the model for testing. Statistical significance was set at P < 0·05. The finalised model was refit with age centred at 12 months to test for group differences in 12-month growth status by breastfeeding duration category.

Poisson regression was used to test for differences in the relative risk of rapid weight gain by breastfeeding duration category, including adjustment for sociodemographic variables. The robust SE were calculated using sandwich error estimation for R and used to construct 95 % CI.

Results

As shown in Table 1, 82 % of the participants were either African American (48 %) or Latino (34 %). Over half of the mothers had graduated from high school or earned a GED (56 %). At the 2-month interview, 38 % were employed full-time or part time; 81 % participated in WIC, and 46 % participated in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Slightly under half (44 %) of the infants were male.

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics overall and by breastfeeding duration categories (n 256)

Percentages rounded. WIC: special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants and children; SNAP: supplemental nutrition assistance program.

* Group of 0–2 months includes 11 % who did not initiate breastfeeding.

† Between-group differences tested using chi-square tests for categorical variables, while for continuous variable, i.e. maternal BMI was analysed using ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD.

‡ ‘Other’ group includes American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian and multiple race/ethnicity.

§ Employment status at enrollment.

Overall, the median breastfeeding duration was 4·75 months. In the 0–2-month category, the median duration was 2 weeks (Table 1), accounting for 11 % who did not initiate breastfeeding. In the 3- to 6-month category, the median duration was approximately 4 months. Among participants who continued breastfeeding for 6+ months, approximately half continued for the entire follow-up period (median = 11·73 months; Table 1).

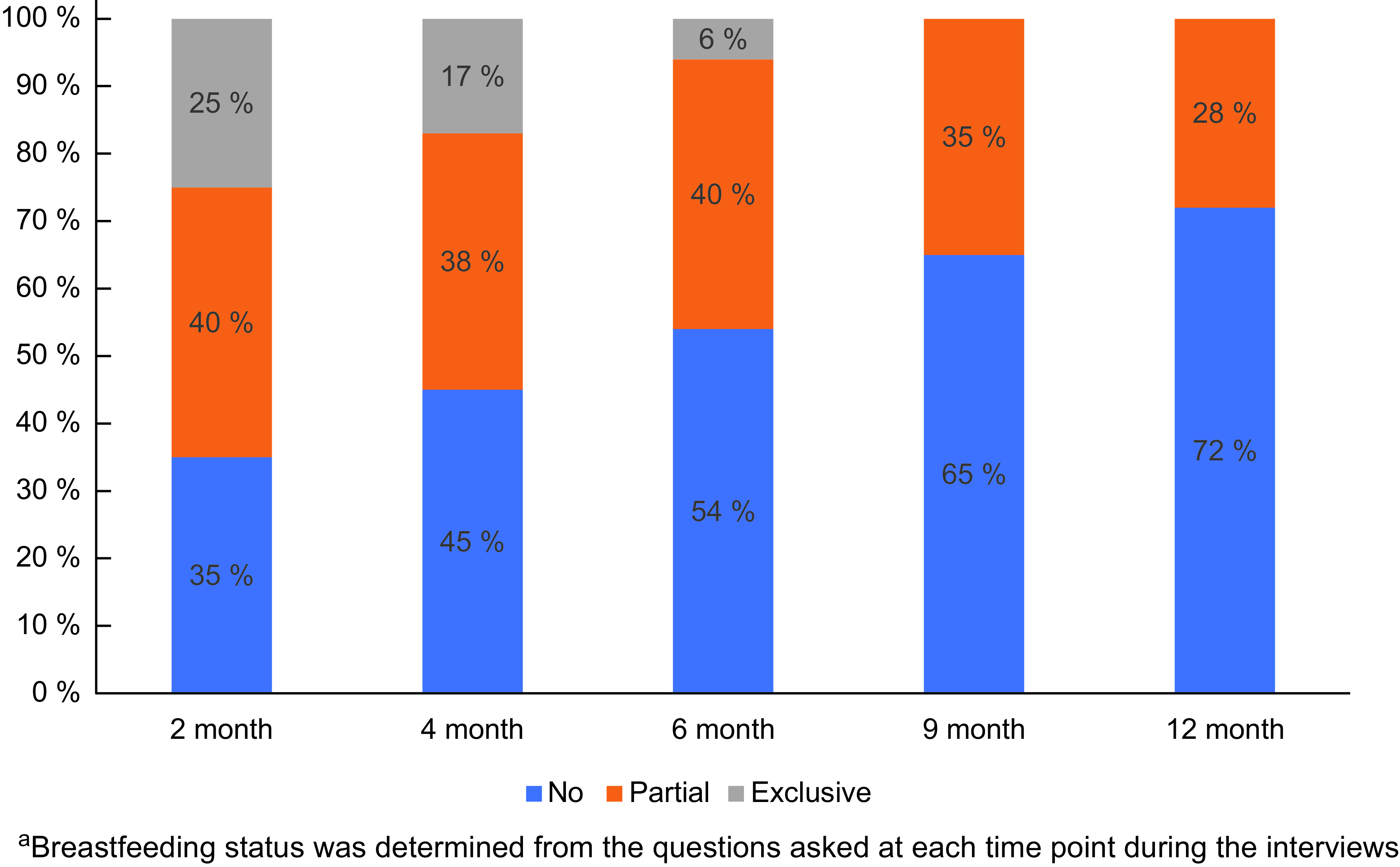

As shown in Fig. 1, at each time point of 2, 4 and 6 months, 65 %, 45 % and 46 % of the mothers, respectively, were either partially or exclusively breastfeeding, with partial more common than exclusive. Based on differences in the percentage of women breastfeeding, the overall discontinuation rate was approximately 10 % between interview time points (2, 4, 6, 9 and 12 months), with 28 % of the mothers reported breastfeeding at 12 months.

Fig. 1 Breastfeeding rates from 2 to 12 months among low-income, racially and ethnically diverse population group (n 256)a.

In comparing breastfeeding groups by sociodemographic characteristics, significant differences were seen by maternal BMI, race, ethnicity, parity, maternal education and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participation (Table 1). Mothers in the 6+ months group had the lowest BMI. Breastfeeding continuation after 6 months was highest among Latino and ‘Other’ groups (Asian, American Indian or mixed ethnicity groups), among multiparous women, among better-educated women (high school or higher) and among non-Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participants.

Weight for length

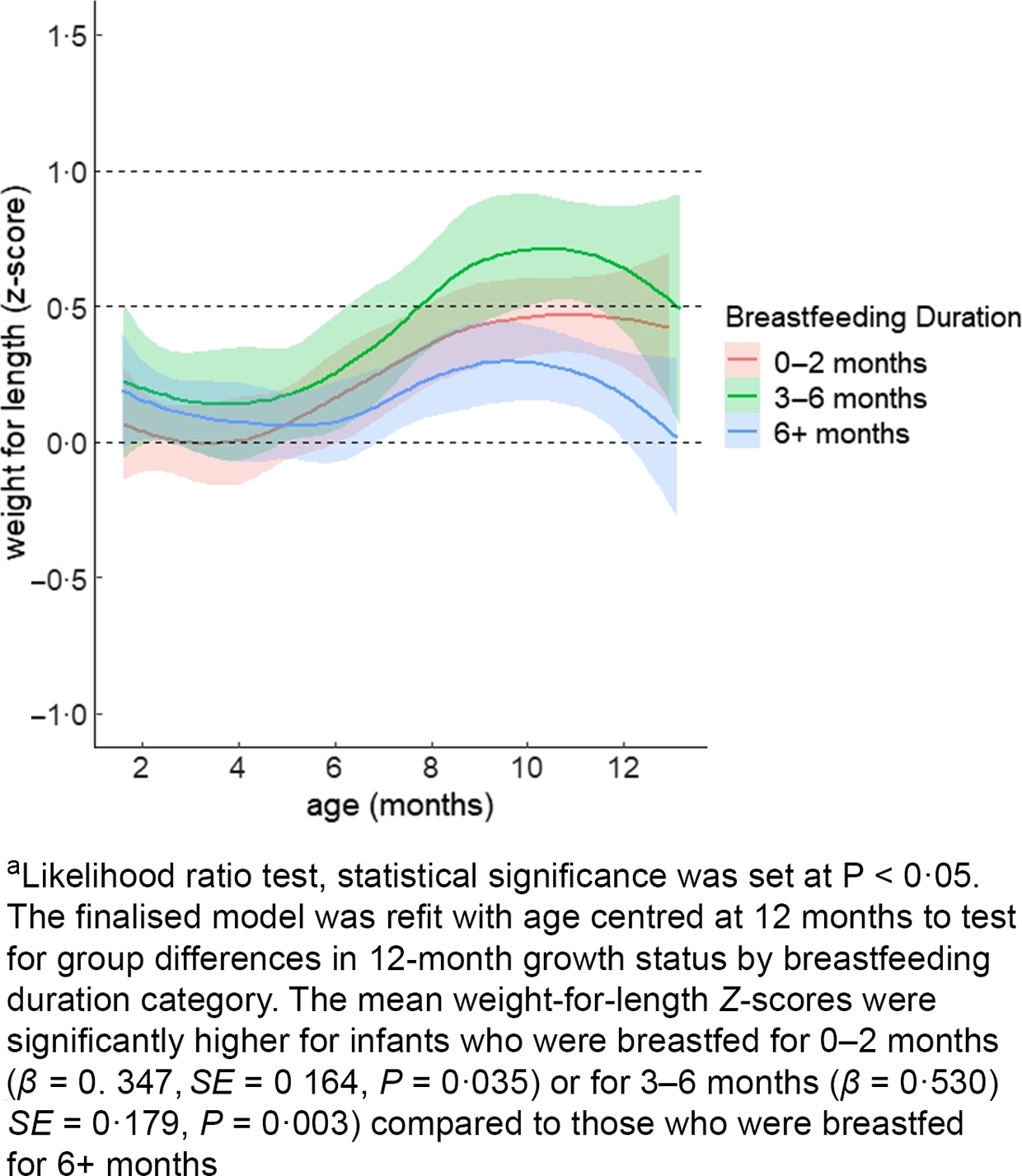

The significant interaction of the linear age term with breastfeeding duration indicated that, on average, the per-month change in the weight-for-length z-score over the first year of life was greater in the 0–2-month group (β = 0·045, se = 0·013, P = 0·001) or the 3–6-month group (β = 0·054, se = 0·016, P = 0·001) compared to the 6+ month group (Table 2). Consistent with these differences in Z-scores, when we refitted the model with time centred at 12 months as shown in Fig. 2, we found that the mean weight-for-length Z-scores were significantly higher for infants who were breastfed for 0–2 months (β = 0. 347, se = 0. 164, P = 0·035) or for 3–6 months (β = 0·530, se = 0·179, P = 0·003) compared with those who were breastfed for 6+ months (Fig. 2).

Table 2 Multilevel growth model to estimate weight-for-length trajectory by breastfeeding duration (n 256)

Independent variable breastfeeding (BF) duration, with 6+ month breastfeeding as a referent; Age x BF 0–2 months and Age x BF 3–6 months are differences in mean linear changes over 12 months in weight for length compared to ‘6+ months’ breastfeeding group.

Age2 and Age3 are quadratic and cubic terms, respectively.

Reference groups for sex: male; race/ethnicity: non-Latino White; education: < high school; parity: primiparous; delivery: vaginal.

Fig. 2 Mean weight-for-length growth trajectory by breastfeeding duration among racially and ethnically diverse group of infants from low-income households (n 256)a.

Rapid weight gain

Thirty-six per cent of the infants experienced rapid weight gain between 2 and 12 months. Compared to the 6+ month group, the risk for rapid weight gain was significantly higher in the 0–2-month group (relative risk (RR) = 1·68, CI95 (1·03, 2·74), P = 0·037) and marginally higher in the 3–6-month group (Table 3). Maternal BMI was positively associated (RR = 1·02, CI95 (1·00, 1·05), P = 0·007) with rapid weight gain among infants, and having a high school diploma or GED was associated with a decreased risk of rapid weight gain from 2 to 12 months of age compared to having less than a high school education (RR = 0·51, CI95 (0·30, 0·85), P = 0·011, Table 3).

Table 3 Risk ratios for rapid weight gain from 2 to 12 months by breastfeeding duration (n 256)

RR: relative risk.

* Poisson regression.

Rapid weight gain was defined as a change of > 0·67 SD in weight-for-age Z-score between 2 and 12 months; employment status at 12 months of infant’s age.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates a positive association between continued breastfeeding during the complementary phase and normal growth trajectories among infants from low-income, racial and ethnic groups.

Among our study population, exclusive breastfeeding was relatively uncommon in the first 6 months, and at 12 months, only 28 % of the participants were breastfeeding. At the national level, the overall breastfeeding rate at 12 months is 35 %(24). However, among infants living below the poverty level, the breastfeeding rate at 12 months is 25 %(24), which is consistent with our findings and highlights breastfeeding inequities. Breastfeeding is influenced, not only by individual factors but also by structural and environmental factors, including health care and support services and workplace policies. The relatively low rates of breastfeeding among women living in poverty may be associated with the absence of maternity leave, hourly work positions with limited time for breastfeeding or lack of access to a facility for pumping and storing milk in safe conditions(Reference Petersen25). Support through paid maternity leave for all working sectors, including hourly and temporary job workers, has been noted to improve breastfeeding support and in turn, potential expected growth among infants(Reference Pérez-Escamilla26). In our study, two-thirds of mothers were not working. Studies have shown that poverty and food insecurity are associated with low breastfeeding self-efficacy and ability to continue breastfeeding(Reference Orr, Dachner and Frank27,Reference Gross, Mendelsohn and Arana28) .

National surveys have found that improvements in breastfeeding initiation, exclusivity and continuation have lagged among the African American group compared to other racial and ethnic groups(24). We found the continuation of breastfeeding after 6 months was lower among the African American group, compared to the Latino group. Breastfeeding discontinuation among African American mothers has been associated with younger age, infants with lower birth weight, lack of higher education and low household income(Reference Safon, Heeren and Kerr29). A history of structural racism has also played a role by affecting African American women’s trust and confidence in the health care system(Reference Petit, Smart and Sattler30). To address these issues, recommendations include reducing implicit bias and racism among healthcare professionals and improving cultural competency of prenatal and postpartum breastfeeding support programmes(Reference Petit, Smart and Sattler30). Among Latina mothers, relatively higher breastfeeding rates have been attributed to having a family history of breastfeeding, high likelihood of living with a partner and close-knit multigenerational social support(Reference McKinney, Hahn-Holbrook and Chase-Lansdale31).

Our study results suggest that breastfeeding throughout infancy is associated with reduced rapid weight gain risk and normal weight status at the end of infancy. Previous studies have also demonstrated this relationship(Reference Zheng, Hesketh and Vuillermin11–Reference Wood, Witt and Skinner13). For instance, Carling et al. (Reference Carling, Demment and Kjolhede12) found that children who were breastfed for <2 months were more likely to experience an accelerated growth trajectory compared to children who were breastfed > 4 months. This relationship was particularly significant among children at elevated obesity risk or children whose mothers had a high BMI, low education and/or smoked tobacco during pregnancy. In linking the association between breastfeeding and normal growth, it is possible that breastfeeding may reduce the amount or frequency of formula feeding. Both the nutrient profile of formula and behaviours associated with formula feeding (e.g. finishing the bottle) may increase the risk of rapid weight gain(Reference Appleton, Russell and Laws32). By nutrient profile, the protein content in infant formulas, which is generally higher than in breastmilk, has been associated with higher infant weight gain(Reference Bell, Wagner and Feldman33). Additionally, formula contains sweeteners such as maltodextrins and corn syrup, significantly contributing to infants’ daily added sugar intake. In a study with 9- to 12-month-old formula-fed infants, formula contributed to 66 % of the daily added sugar intake and, in turn, was significantly associated with rapid weight gain(Reference Kong, Burgess and Morris34). Among formula-fed infants, practices such as putting an infant to bed with a bottle, adding cereal to bottles and pressuring an infant to finish the bottle, have been shown to increase daily energy intake among infants(Reference Appleton, Russell and Laws32). These behaviours are also applicable to pumped breastmilk feeding. We did not have information on whether infants were breastfed directly or given pumped breastmilk through a bottle. An observation study comparing breastmilk intake directly v. pumped milk from a bottle found that a pressurised feeding style, rather than the mode of feeding, predicted milk intake(Reference Ventura, Hupp and Lavond35). Another study, involving 2553 infants and three feeding modes, found that at 12 months, the formula-fed group had the highest BMI Z-scores, followed by the expressed/bottled breastmilk group, and the leanest were the direct breastfeeding group(Reference Azad, Vehling and Chan36).

In the recent past, exclusive breastfeeding rates have increased nationally(24). National programmes, including the baby-friendly hospital initiative(Reference Walsh, Pieterse and Mishra37) and the WIC programme, which serves half of the infants in the U.S.(Reference Walsh, Pieterse and Mishra37), have been critical in not only increasing breastfeeding initiation rates but also advancing policies and programmes to support continued and coordinated breastfeeding services(Reference Walsh, Pieterse and Mishra37). WIC breastfeeding support services and interventions, including text messaging, group education sessions and economic incentives have been effective in improving continuation and intensity of breastfeeding among mothers with limited resources(Reference Segura-Pérez, Hromi-Fiedler and Adnew38). For instance, a randomised controlled trial found that the intervention, which included a monetary incentive in addition to WIC breastfeeding support, was effective in improving breastfeeding continuation up to 6 months(Reference Washio, Humphreys and Colchado39).

A major strength of our study is the prospective collection of breastfeeding status along with infant growth measurements. Our focus on African American and Latina mothers from low-income settings helps to fill the gap in understanding the protective role of continued breastfeeding among populations experiencing disproportionate burden of childhood obesity. In addition to replication, further research is needed to examine generalizability to other settings as well as whether the positive association between breastfeeding duration and healthy growth persists after 12 months.

There are also several limitations. First, women who were not breastfeeding may have refused to join a study that asked about breastfeeding. Likewise, breastfeeding mothers may have overreported breastfeeding rates, due to perceived social desirability bias. Second, due to limitations of our HIPPA agreement, we did not have access to birth weight and therefore we used 2-month weight status as a baseline, potentially reducing the accuracy of average growth rate. Third, the study lacked the sample size to compare weight gain trajectory by exclusive v. mixed breastfeeding and mode of feeding (direct v. pumped). In the future, such analysis is warranted to fully understand the associations between breastfeeding patterns and rapid weight gain.

In summary, our study provides information on breastfeeding continuation patterns among racially and ethnically diverse groups of mothers from low-resource settings. Our findings that breastfeeding continuation beyond 6 months is associated with the prevention of rapid weight gain, a precursor of obesity, suggest progress toward health equity.

Acknowledgements

We thank the pediatric clinic staff for their assistance in recruiting mothers of young infants. We appreciate participants’ time and efforts in participating in interviews at regular intervals. We also want to acknowledge Mitchell Zaplatosch who assisted with data analysis, reporting and presentation. Individuals named in this acknowledgement have given their permission.

Financial support

The study is funded by NIH-NICHD 1 R15 HD095261-01.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Authorship

J.M.D.: Conceptualised and led the study and had the primary role in the writing process. C.F.: Coordinated recruitment and retention strategies, participated in the data collection and worked in organising the manuscript for final submission. J.L.: Conducted statistical analysis and assisted with interpretation and drafting of statistical results. M.M.B.: Assisted in data interpretation of the results and refined the framework of the paper. All authors reviewed drafts, provided comments and approved the final version.

Ethics of human subject participation

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board. Written or verbal informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients. Verbal consent was witnessed and formally recorded.