Adolescence is a critical period of life characterised by rapid growth and development, both physically and psychologically( Reference Tanner 1 , Reference Eccles 2 ). Changes in physical appearance make adolescents, particularly girls, self-conscious about their bodies( Reference Rand, Resnick and Seldman 3 – Reference Vilhjalmsson, Kristjansdottir and Ward 5 ). Body image conception of an individual may or may not match with the objective reality. As a consequence, in spite of being within a healthy weight range, a girl may become seriously concerned about her body weight and shape( Reference Jovanovic, Lerner and Lerner 6 – Reference Weinshenker 8 ). Western societies introduce the concept of a slim and slender body for females as the symbol of physical attractiveness and beauty. This concept seems to develop dissatisfaction with body weight and shape among adolescent girls( Reference Garner, Garfinkel and Schwartz 9 , Reference Wiseman, Gray and Mosimann 10 ). Preoccupation with thinness enhances weight-related stigmas and subsequent eating concerns among girls( Reference Bruch 11 – Reference Grigg, Bowman and Redman 13 ). The impact of this socially stereotyped thin body image is largely promoted by the pervasiveness of mass media( Reference Tiggemann and Pickering 14 – Reference Becker, Burwell and Herzog 17 ). Additionally, mothers’ encouragement towards girls’ weight-loss attitudes and mothers’ own eating practices( Reference Pike and Rodin 18 – Reference Cromley, Neumark-Sztainer and Story 20 ) and peer influences( Reference Vincent and McCabe 21 , Reference Lieberman, Gauvin and Bukowski 22 ) become the major forces of motivation for adopting weight-reducing eating habits among girls.

The rising incidence of obesity among adolescent girls develops a discrepancy between their body image perception and cultural expectations( Reference Paxton, Eisenberg and Neumark-Sztainer 23 , Reference Sanchez-Villegas, Field and O’Really 24 ). As a result, overweight and obese girls show greater risk of weight-related physical and psychosocial consequences( Reference Sanchez-Villegas, Field and O’Really 24 , Reference Stice, Presnell and Shaw 25 ) and adopt a variety of weight-reducing eating habits( Reference Serdula, Collins and Williamson 26 ). They are more likely to follow unhealthy eating practices (like binging, skipping meals, starving for the whole day, use of laxatives and diet pills) rather than healthy eating practices (like consumption of nutritious foods, reduction of fat intake)( Reference Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan 27 , Reference Vander Wal 28 ). The major public health concern centres on the fact that not only overweight girls but also normal-weight and underweight girls follow unhealthy weight-reducing measures, with a desire to be thin. Misconception about body weight also prevails among them, irrespective of their weight status( Reference Boutelle, Neumark-Sztainer and Story 29 ).

Concerns about weight and eating practices are also reported for African and Asian adolescents( Reference Caradas, Lambert and Charlton 30 – Reference Sakamaki, Amamoto and Mochida 34 ). Unhealthy eating attitudes are found to be common among South African schoolgirls of different ethnic backgrounds( Reference Caradas, Lambert and Charlton 30 ). Studies in South Asian countries reveal that girls, irrespective of their weight status, follow beauty standards of Western cultures; however, their eating behaviours fail to show significant differences( Reference Wan, Kandiah and Taib 31 , Reference Sakamaki, Amamoto and Mochida 34 ).

In India, with the advent of modernisation, eating and weight concerns are increasing alarmingly among urban adolescent girls as a consequence of the rising incidence of body fat, although a plump body shape is preferred in traditional Indian culture. A few studies show that Indian adolescent girls express a milder form of weight dissatisfaction with added extreme fear of fatness( Reference Srinivasan, Suresh and Jayaram 35 ) and subsequently attempt to achieve a slim and trim body shape by following various weight-loss measures( Reference Chugh and Puri 36 – Reference Stigler, Arora and Dhavan 38 ). Therefore, it seems that unhealthy weight-related behaviours seriously affect their physical and mental abilities at this vulnerable phase of growth( Reference Augustine and Poojara 39 ). With this backdrop, the present study aims to examine the associations of body weight and body shape concerns and related behaviours with actual weight status among urban adolescent girls.

Materials and methods

Study area

The present cross-sectional study was conducted in the twin cities of Kolkata and Howrah, districts of West Bengal, located in the eastern part of India.

Study population

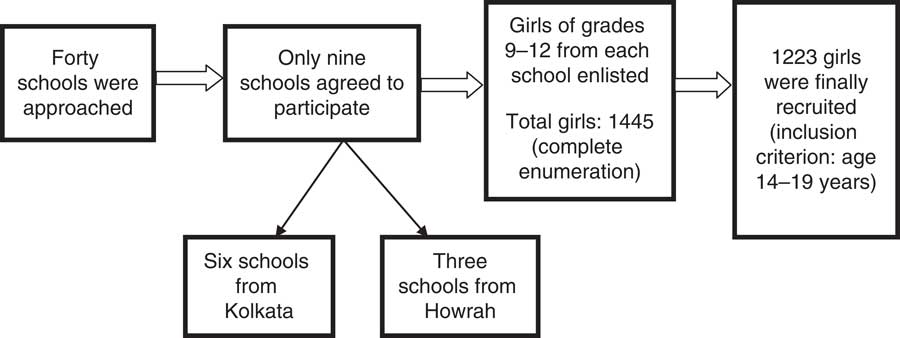

Initially, a list of 100 schools for girls within the study area was prepared. Out of these, forty schools were chosen randomly and approached for permission. Only nine (22·5 %) schools granted permission to conduct the survey. A total of 1445 girls were enlisted following the complete enumeration method from grades 9 to 12 of those selected nine schools. Of them, 1223 girls were finally selected on the basis of the sole inclusion criterion, i.e. age (14–19 years). Among those (n 222) who could not participate, 20 % were outside the age range, while 33 % were not present during the time of survey and the rest (37 %) did not receive parental consent (Fig. 1). Written informed consent was obtained from the principal of each school and the parent of each participating girl prior to the study, while verbal assent was obtained from each of the girls participating in the survey. The data were collected during February 2011 to December 2012. Overall study objectives, methods and instruments used were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Indian Statistical Institute.

Fig. 1 Flowchart showing the enrolment of girls in the present study

Data collection

Sociodemographic measures

Data on the age of the girls, education level and occupation type of both parents and monthly household expenditure were collected using a pre-tested schedule.

Anthropometric data and weight status

Height and weight of the adolescent girls were measured by one of the authors (N.S.). Height was measured to the nearest of 0·1 cm using a portable GPM anthropometer and weight was measured to the nearest of 0·1 kg for each participant in light clothing without shoes using a Tanita digital scale (Tanita-TBF-521). BMI was calculated using the formula: BMI=[weight (kg)]/[height (m)]2. Calculated BMI was translated into an age- and sex-specific BMI Z-score using the cut-off points based on reference data from the WHO( 40 ). Girls were categorised as underweight/thin (BMI-for-age Z-score <−2), normal weight (BMI-for-age Z-score of −2 to 1), overweight (BMI-for-age Z-score of 1 to 2) and obese (BMI-for-age Z-score >2). The few obese girls (with BMI-for-age Z-score >2) were combined with overweight girls to make the ‘overweight group’.

Measures of body weight and body shape concerns and related behaviours

Body weight and body shape concerns and related behaviours were assessed with a self-administered questionnaire, adapted and slightly modified from the questionnaires used in other studies( Reference Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan 27 , Reference Mciza, Goedecke and Steyn 32 , Reference Story, Stevens and Evans 41 ). The original version of the questionnaire was in English. Since Bengali is the vernacular language of the study population, it was translated into Bengali and back-translated into English for validation by professional translators. This self-administered questionnaire included twenty-two questions, each with dichotomous response choices (Table 1).

Table 1 Body weight and body shape concerns and related behaviours

Data analysis

Data were analysed using the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20. Descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage) were computed to understand the trends in sociodemographic profile of the participating girls. The χ 2 test was used to show the association of actual weight status with each of the variables considered for body weight and body shape concerns and related behaviours. Multivariate binary logistic regression (stepwise) was carried out for each of the variables designed for body weight and body shape concerns and its related behaviours to show the association with actual weight status of the girls after adjusting for the effects of sociodemographic variables. Actual weight status of the girls and other sociodemographic variables (age of the girls, education level and occupation type of both parents, monthly household expenditure) were included as covariates in each model. Each of the variables considered for body weight and body shape concerns and related behaviours was incorporated as a dependent variable for each separate model. However, several weight-loss measures (eating more fruits and vegetables, reducing fat intake, fasting, using food supplements) and only one weight-gain measure (eating more fatty foods) were not used as dependent variables as their response rate was low. Before performing regression analyses, a multiple imputation method was applied to replace the missing values in the sociodemographic variables (education level and occupation type of both parents, monthly household expenditure). Each of the sociodemographic variables (except age of the girls) was converted into dummy variables. A P value of ≤0·05 was considered statistically significant and only significant predictor variables are presented with odds ratio and 95 % confidence interval. Weighted κ with 95 % confidence interval was calculated to understand the degree of agreement between perception and self-categorization of weight status. A κ of 0·41–0·60 indicates ‘moderate’ agreement( Reference Viera and Garrett 42 ). Sensitivity and specificity of self-judgement of overweight status against actual weight status were also measured. The Kuder Richardson index-20 was calculated to judge the reliability of the questionnaire and the tested value was 0·73, which indicated that the test result proved to be acceptable.

Results

Sociodemographic profile

The study initially included 1445 girls from a wide range of sociodemographic profiles. The total response rate was 84·6 %. Table 2 portrays the sociodemographic profile of the girls. Most of the girls were aged between 14 and 15 years (52·3 %) and belonged to a family with monthly household expenditure of Rs 8000–20 000 (43·4 %). Parents’ attained education was mostly below the graduation level (fathers, 50·3 %; mothers, 62·5 %). More than 80 % of mothers were home makers and fathers were mostly (65·6 %) in service.

Table 2 Sociodemographic profile of the adolescent girls, Kolkata and Howrah, West Bengal, India, February 2011–December 2012

Rs, Indian rupees.

* Others: private tutor, pension holder.

† Others: maid servant, private tutor.

Body weight and body shape concerns and actual weight status of girls

Table 3 shows that most of the girls perceived their weight status in accordance with their actual weight status, although exceptions were also noticed. For example, 39·7 % of underweight girls misperceived themselves as of normal weight; 1·3 % of underweight girls and 10·7 % of normal-weight girls misperceived themselves as overweight. Most of the overweight girls were found to be dissatisfied with their present weight status. However, a substantial proportion of normal-weight and underweight girls were found to be happy with their actual weight status. Actual weight status showed significant associations with body weight and body shape perception, body weight dissatisfaction and distress regarding body shape. A high percentage (78·8 %) of overweight girls perceived themselves as fat and also expressed distress (74·6 %) regarding their fatness. Additionally, several normal-weight girls (29·5 %) and a few underweight girls (3·8 %) failed to show proper perception regarding their body shape. They inaccurately reported themselves as fat. More than 30 % of normal-weight girls and 10·3 % of underweight girls also expressed fear of becoming fat.

Table 3 Body weight and body shape concerns according to actual weight status among the adolescent girls (n 1223), Kolkata and Howrah, West Bengal, India, February 2011–December 2012

Body weight- and body shape-related behaviours and actual weight status of girls

Body weight- and body shape-related behaviours of the adolescent girls with respect to their actual weight status are documented in Table 4. The majority of overweight and normal-weight girls were found to engage in weight-reducing activities. However, underweight girls mostly attempted to gain weight. Girls followed several measures to lose weight, which could be categorised as both healthy and unhealthy. Healthy measures, such as vigorous physical exercise, consumption of fruits and vegetables and reduced fat intake, were followed by 3·8 % of underweight, 17·9 % of normal-weight and 39·9 % of overweight girls. Similarly, unhealthy measures, such as fasting, eating fewer foods than required, skipping meals and using food supplements, were found to be adopted by 5·1 % of underweight, 29·4 % of normal-weight and 69·8 % of overweight girls. On the other hand, underweight girls mostly followed healthy weight-gain measures such as eating larger portions of foods (51·3 %), moderate physical exercise (9·0 %), eating more meals in a day (11·5 %) and use of food supplements (16·7 %). Girls attempted to gain weight mostly by eating larger portions of foods. Physical exercise was the least adopted healthy activity among them.

Table 4 Body weight- and body shape-related behaviours according to actual weight status among the adolescent girls (n 1223), Kolkata and Howrah, West Bengal, India, February 2011–December 2012

* The χ 2 test was not performed due to the presence of two cells with zero value in the variable considered for unhealthy measures.

Multivariate analyses

In Table 5, results of multivariate binary logistic regression analyses (stepwise) reveal that after adjusting for sociodemographic factors, actual weight status of the girls significantly predicted all of the variables considered for body weight and body shape concerns. As compared with normal-weight girls, overweight girls were more likely to perceive themselves as overweight and fat, be dissatisfied with body weight and express fear of becoming fat. Similarly, the likelihood of showing concerns over body weight and shape was significantly higher for underweight girls compared with their normal-weight counterparts. Weight-related behaviours of the girls were found to be significantly predicted by their actual weight status after adjusting for the effects of sociodemographic factors (Table 6). The association between actual weight status and unhealthy eating practices was significant. Overweight girls were more likely to report weight-reducing attitudes and to follow several weight-loss measures. Underweight girls tended to follow several weight-gain measures. This relationship remained statistically significant in multivariate analysis.

Table 5 Multivariate binary logistic regression analyses (stepwise) using each of the variables considered for body weight and body shape concerns as a dependent variable; adolescent girls (n 1223), Kolkata and Howrah, West Bengal, India, February 2011–December 2012

Rs, Indian rupees; Ref., reference category.

* Others: maid servant, private tutor.

† Others: private tutor, pension holder.

Table 6 Multivariate binary logistic regression analyses (stepwise) using each of the variables considered for body weight- and body shape-related behaviours as a dependent variable; adolescent girls (n 1223), Kolkata and Howrah, West Bengal, India, February 2011–December 2012

Ref., reference category.

* Others: private tutor, pension holder.

Agreement between actual and perceived body weight status of girls

A weighted κ value of 0·52 in Table 7 indicates that there was moderate agreement between actual and perceived body weight status of the girls. We also examined the sensitivity and specificity of self-judgement of overweight status against actual weight status. The sensitivity was moderately high, indicating that actual overweight girls (58·9 %) truly judged themselves as overweight. The specificity value was remarkably higher, indicating that more than 90 % of non-overweight girls correctly identified their weight status. With moderate sensitivity and high specificity value, the test result proved to be good.

Table 7 Estimated sensitivity, specificity and weighted κ for agreement between body weight perception and actual weight status of adolescent girls (n 1223), Kolkata and Howrah, West Bengal, India, February 2011–December 2012

Discussion

The present cross-sectional study attempts to evaluate the associations of body weight and body shape concerns and related behaviours among a group of urban adolescent girls with their actual weight status. The present findings suggest that body weight and body shape concerns and related behaviours are largely associated with the actual weight status of these girls. Overweight girls are more likely to report use of several weight-loss strategies along with the prime concerns over body weight and shape compared with their normal-weight and underweight counterparts.

The number of overweight girls in both developed and developing countries is increasing steadily( Reference Hedley, Ogden and Johnson 43 – Reference Wu 45 ). Consequently, an urge to be thin following several weight-reducing practices has become an increasing trend among overweight youth( Reference Stigler, Arora and Dhavan 38 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Hannan 46 ). These weight-reducing behaviours sometimes involve the use of several unhealthy measures( Reference Boutelle, Neumark-Sztainer and Story 29 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Hannan 46 ). In our study, concerns over body weight and shape and the practice of weight-related behaviours are prevalent among overweight girls. Less than three-fifths of overweight girls rightly perceive themselves as overweight and the rest mostly misperceive themselves as normal weight. A large number of overweight girls express dissatisfaction with body weight and shape. Earlier studies show that rates of adopting weight-reducing strategies are high among overweight girls compared with their non-overweight counterparts( Reference Stigler, Arora and Dhavan 38 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Hannan 46 ). These findings are consistent with our results. It could be an indication of either their perception of being normal weight or their perceived hopelessness towards weight reduction. These overweight girls are mostly engaged in unhealthy eating practices of reducing body weight other than physical exercise. A combination of these, i.e. healthy food habits and adequate physical exercise, would have been an ideal measure of weight reduction for them.

Our study shows that most of the normal-weight girls perceive their weight status accurately, although a few of them express dissatisfaction with body weight. They are more concerned about fat body shape rather than body weight. In order to reduce body weight, this group is also shown to follow more unhealthy measures (in terms of foods and activities) than healthy ones. Therefore, it seems that normal-weight girls are motivated to achieve a thin body shape and they decide to follow harmful steps towards the goal. One longitudinal study in the USA shows that improper eating behaviours are positively associated with rapid weight gain instead of weight loss( Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Wall and Guo 47 ). Interestingly, weight-related misconception is found to be common among the girls who are actually underweight. These girls perceive themselves to be of normal weight, but a few remain distressed with body shape. Incidentally, this group of underweight girls is mostly shown to follow healthy weight-gain measures, although a few of them are engaged in unhealthy eating practices.

Strengths of the present study include a large study population that allows more generalisation and contributes to the current body of literature. Anthropometric measurements on height and weight for each girl account for another study strength. Self-reported behaviours including use of both weight-loss and weight-gain measures show variability of the data. The data on body weight and body shape concerns and related behaviours from a unique study group with varied sociodemographic characteristics possibly add a dimension to look into the issue. One of the limitations of the study is its cross-sectional nature that fails to study the effects of change over time in the concerns and behaviours related to body weight and body shape for the same individual. In addition, adolescents may distort their weight concerns and behaviours by either under-reporting or over-reporting.

Conclusion

It is evident from the present study that Indian adolescent girls are involved in the whirlpool of body weight- and shape-related dilemmas following their Western counterparts. To achieve the desired weight status and body shape they often are caught in the web of ignorance and myths and subsequently develop unhealthy eating practices. Adoption of several weight-reduction behaviours by adolescent girls becomes matter of concern when merely out of fear of getting obese; both normal-weight and underweight girls follow this path. Therefore, the potential threats of both long-term and short-term outcomes of unhealthy eating behaviours demand serious attention for adolescent girls. Findings suggest that health education programmes should be adopted by schools to promote strategies on appropriate weight-control practices that help dispel the myths about weight loss.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to express their gratitude to the study participants and the schools that participated in the study. They are most thankful to Dr Sharon R. Williams (Assistant Professor in the Department of Anthropology, Purdue University) and Dr Gillian H. Ice (Associate Professor of Social Medicine and Director of Global Health in the Department of Social Medicine and Office of Global Health, Ohio University) for improving the language of the manuscript. They are also thankful to Dr Sourav Ghosh and Baidyanath Pal of the Indian Statistical Institute in Kolkata for their valuable comments during the analyses of data. Financial support: The study was supported by a grant from the Indian Statistical Institute. The Indian Statistical Institute had no role in the design of the study, analysis of the data or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: Both the authors were responsible for the set up of the study, analyses and interpretation of the data and writing of the manuscript. Data collection was done mostly by N.S. Ethics of human subject participation: Overall study objectives, methods and protocols used in the study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Indian Statistical Institute.