The prevalence of overweight including obesity has increased rapidly amongst women in African countries, from 33·0 % in 2000 to 42·9 % in 2016(1). North African and Southern Sub-Saharan African women experience the second and third highest prevalence of overweight and obesity of the twenty one global burden of disease regions(Reference Kengne, Bentham and Zhou2), which are higher than the global average(Reference Ng, Fleming and Robinson3).

Current literature suggests that there are underlying social and cultural factors related to body image, such as a preference for larger body sizes, contributing to the increasing prevalence of obesity in African females(Reference Prentice4,Reference Gatineau and Mathrani5) . Body size preference plays a role in healthy weight behaviours. It is defined as an individual’s perception of how acceptable their body is to themselves and society(Reference Burrowes6). This includes body image dissatisfaction that may contribute to attempting to achieve an ideal body image leading to a desire for weight loss or weight gain(Reference Sarwer, Thompson and Cash7). Body dissatisfaction (for slimness) may be one of the key drivers of the obesity epidemic in African women and adolescent girls. A cultural preference for a heavier body size is thought to lead to greater body satisfaction of African women at larger body sizes(Reference Rguibi and Belahsen8). In addition, body dissatisfaction might promote weight gain in slimmer women trying to fit in with cultural norms. For example, Moroccan Sahraouian women actively engage in fattening behaviours to attain the desirable body size within their community(Reference Rguibi and Belahsen9). Fatness is a sign of femininity, fertility and being a nurturing mother. Women’s primary role in these societies is associated with motherhood, therefore, ‘being fat’ elevates females’ status by embodying their suitability for this role(Reference Brown and Konner10,Reference Batnitzky11) . Historically, fatness was viewed as a sign of wealth, signifying excess resources in settings where food shortages were common and also demonstrating that women were well taken care of by their husbands(Reference Batnitzky11).

This preference for a larger body size in women can be explained by evolutionary benefits. Prior to the industrialisation of food production, food shortages were common in all societies; therefore, storing fat improved survival(Reference Brown and Konner10,Reference Caballero12) . This was particularly important for women of childbearing age, meaning fatter women would be more successful in pregnancy and childbearing(Reference Brown and Konner10,Reference Lain and Catalano13) . Notwithstanding, in certain African communities, weight gain during pregnancy is perceived negatively due to the fear of complications during delivery(Reference Perumal, Cole and Ouédraogo14–Reference Huybregts, Roberfroid and Kolsteren16). The belief that fatness represents an advantage for pregnancy and childbearing might persevere in some African societies due to the persistence of undernutrition secondary to poverty, particularly in rural areas(Reference Bain, Awah and Geraldine17), potentially making fatness desirable, by setting one apart from the community and embodying excess in resource poor settings(Reference Brown and Konner10). This is supported by the positive association between socio-economic status (SES) and obesity in low-income African countries(Reference Cohen, Rai and Rehkopf18,Reference Ziraba, Fotso and Ochako19) , whereas in high-income countries (HICs) the opposite is observed(Reference Dinsa, Goryakin and Fumagalli20). In African middle-income countries, the association between SES and obesity is negative for women(Reference Dinsa, Goryakin and Fumagalli20). Furthermore, Western body size preferences have shifted towards a slimmer body size, whilst the population’s mean BMI has increased, suggesting that body size preferences evolve to contradict societal norms(Reference Bakhshi21,Reference Swami22) .

An aversion to ‘thinness’ may also exist in low-income African countries because of stigmatisation associated with disease, for example, HIV and tuberculosis (TB)(Reference Ezekiel, Talle and Juma23,Reference Matoti-Mvalo and Puoane24) .

In addition to cultural factors contributing to body size preference, studies from HICs have reported that being overweight, media exposure and psychological factors contribute to higher body dissatisfaction(Reference Burrowes6,Reference Tunaley, Walsh and Nicolson25–Reference Musaiger and Al-Mannai28) . Younger females are more likely to want to change their body size to fit emerging societal norms valuing thinness(Reference Burrowes6). Therefore, access to ‘Western’ media in Africa might increase the value of slimmer bodies, particularly amongst younger African females. Adolescence signifies the onset of puberty, which increases awareness of body image directly and indirectly via a greater importance placed on peer perceptions(Reference Jones, Smolak and Levesque29). Indeed, studies have reported an increased ‘drive for thinness’ in Black South African adolescents when compared with their White South African counterparts. This contradicts studies of fattening practices in African women(Reference Rguibi and Belahsen9,Reference Brink30) . This might be a result of transitioning cultural norms and generational differences.

In light of the increasing obesity epidemic in African women and the contradictory results reported from the studies discussed earlier(Reference Rguibi and Belahsen8,Reference Brink30–Reference Carney and Louw32) , this paper presents the results of a mixed methods systematic review, to assess body size preferences for African women and adolescent girls living in Africa and the factors influencing these preferences.

Methods

Review typology

A mixed methods systematic review was chosen as it combines quantitative and qualitative evidence(Reference Grant and Booth33) generating a complete, and deeper understanding of women’s body size preferences and the factors influencing these (PROSPERO #: CRD42015020509).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

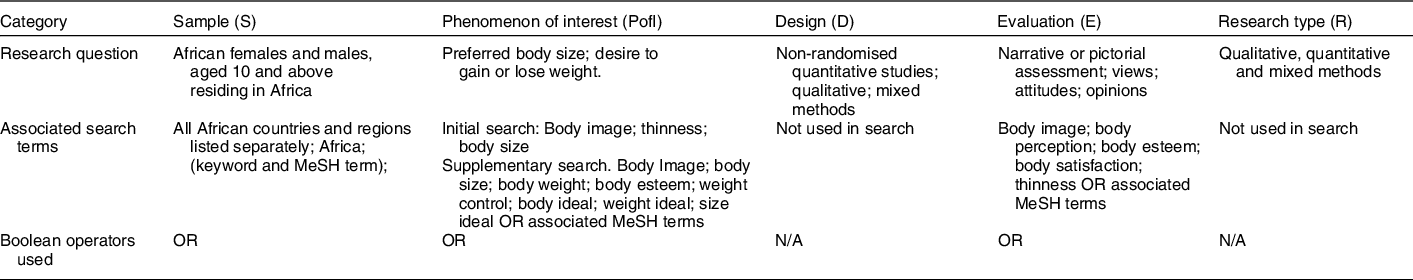

Inclusion criteria were based on the SPIDER tool (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation and Research Type) (Table 1). Studies conducted in any African country among female adolescents (10–19 years) and women (≥18 years) were included. The review focused exclusively on Black African or Arab females. All studies that assessed preferred body size of African females (adolescent girls and women) using narrative and/or pictorial measures, and those that elicited factors influencing these preferences were included. Furthermore, studies assessing African males’ preferences for African females’ body size were included. All non-randomised quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods studies were eligible for inclusion.

Table 1 SPIDER breakdown of research question and search terms

Final Search Strategy: S AND PofI or E * NOT African-American AND *limited to humans.

Search strategy

The SPIDER tool was used to define search terms and eligibility criteria(Reference Cooke, Smith and Booth34). The search was conducted on ASSIA, CINAHL, Medline, PsycINFO and Web of Science. Initial searches were conducted from 20/04/2015 until 15/05/2015. A supplementary search was then conducted, repeating the search strategies up to 31/08/2019. An example full search can be found in online Supplemental Material 1. Furthermore, the reference lists of studies included after full text screening were searched and topic experts consulted to identify additional studies.

Screening

Duplicates were removed in MS Excel before screening. All papers were first screened on titles and abstracts and then on full text in MS Excel (OO, EC, RP, MH, CBN). Reasons for exclusion were recorded at full-text stage (i.e. no measure of body size preferences or factors influencing these; data not stratified by gender, ethnic group or country). To ensure consistency in the application of inclusion criteria, two authors (HO and CBN) checked 10 % of all excluded documents screened. There was a good degree of concordance overall; discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Data extraction

Data extraction of included studies was conducted in MS Excel by OO, EC, RP, MH, HO. Quantitative and qualitative data from mixed methods studies were extracted separately (see online Supplemental Material 2).

Data extracted from studies included general information (study ID, title, authors, date, study location (country, urban v. rural), study aim); study eligibility (participant selection, sample size, participant characteristics); method used to measure body image dimensions; ideal body size; body size self-assessment; body size self-satisfaction and factors influencing body size preferences. One author (RP) checked the full data extraction file to ensure accuracy and consistency across team members. Where data could not be extracted, authors were contacted to request relevant data, e.g. disaggregated data for pooled male and female samples.

Quality appraisal

The ‘Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields’ (QualSyst) was used to critically appraise both the quality of the studies and their reporting(Reference Kmet, Lee and Cook35). This tool was chosen because it provided a standard checklist for all study designs(Reference Kmet, Lee and Cook35). Each study included in the review was rated using a predefined list of criteria (n 14 for quantitative studies, n 10 for qualitative studies). The original tool was modified by replacing the score for each criterion (0, 1, 2) with a qualitative assessment of high quality/green (low risk of bias), medium quality/yellow or low quality/red (high risk of bias) as the Cochrane guidance advises against the use of scores(Reference Higgins and Green36). Five authors (OO, EC, RP, MH, HO) independently conducted quality appraisal and this was double-checked by RP and EC. Discrepancies in the rating were discussed until agreement was reached.

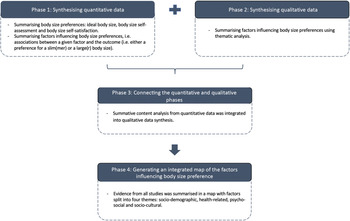

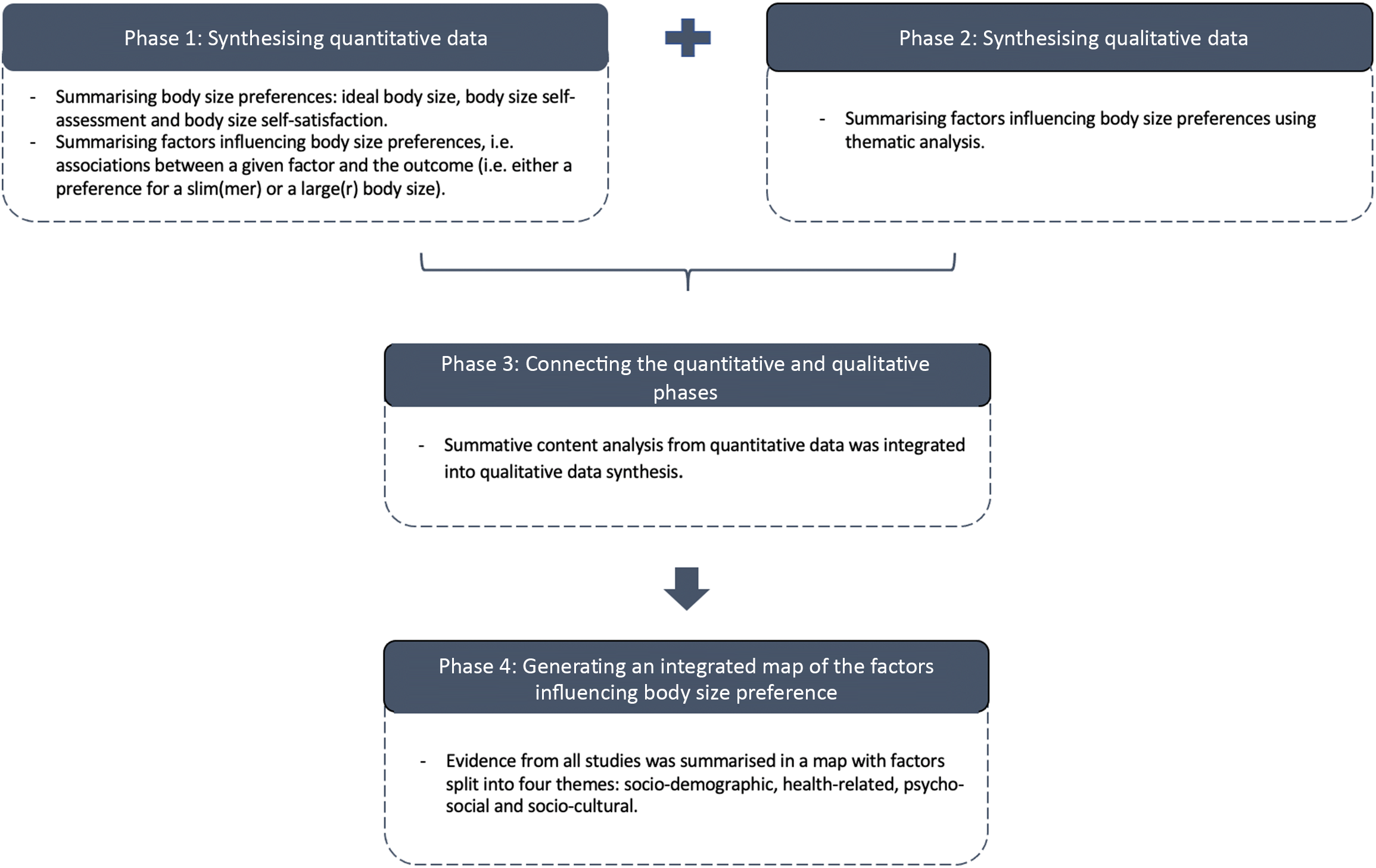

Data synthesis

A sequential-explanatory approach was used to integrate quantitative and qualitative evidence(Reference Pluye and Hong37,Reference Ivankova, Creswell and Stick38) (Fig. 1). In phase one, quantitative studies were synthesised to define African females’ body size preferences and the factors influencing these. Phase two involved summarising the evidence from qualitative studies on factors influencing body size preferences, and phase three aimed at integrating findings from both quantitative and qualitative studies. The qualitative data synthesis provided contextual and cultural understanding of the quantitative data. Phase four focused on generating an integrated (quantitative and qualitative evidence) visual map to represent factors associated with body size preferences.

Fig. 1 Visual model for mixed methods sequential explanatory design procedures

Phase 1: Summarising body size preferences quantitatively and factors influencing these

To identify and summarise body size preferences, we focused on three specific body image dimensions: ideal body size, body size self-assessment and body size self-satisfaction(Reference Gradidge, Golele and Cohen39).

Ideal body size, assessed with various body image (i.e. figural/photographic rating) scales in several quantitative and mixed methods studies, was synthesised graphically where possible. To facilitate the comparison between studies using different scales, females’ ideal body size mean and males’ ideal body size mean for women and adolescent girls were converted into the four main BMI categories: underweight, normal weight, overweight and obesity, through the Silhouette Photographs scale presenting a convenient body image metric(Reference Holdsworth, Gartner and Landais40).

For scales with real BMI values(Reference Holdsworth, Gartner and Landais40–Reference Cohen, Boetsch and Palstra42), we matched BMI categories with each silhouette. For scales without real BMI values, we assigned a BMI category to each silhouette according to the BMI classification defined by authors of the selected articles below. For all articles using the Figure Rating Scale (FRS)(Reference Stunkard, Sørensen and Schulsinger43), the Body Image Instrument(Reference Pulvers, Lee and Kaur44), the Contour Drawing Rating Scale(Reference Thompson and Gray45), the Body Image Assessment for Obesity(Reference Williamson, Womble and Zucker46), the Ideal Body Subscale(Reference Furnham and Alibhai47), the Figural Stimuli(Reference Duda, Jumah and Hill48), the Body Silhouette Chart(Reference Bell, Kirkpatrick and Rinn49) and the Body Size Silhouettes(Reference Liburd, Anderson and Edgar50), we used respectively the BMI classification stated by Matoti-Mvalo and Puoane(Reference Matoti-Mvalo and Puoane24), Pulvers et al. (Reference Pulvers, Lee and Kaur44), Thompson and Gray(Reference Thompson and Gray45), Ettarh et al. (Reference Ettarh, Van de Vijver and Oti51), Cogan et al. (Reference Cogan, Bhalla and Sefa-Dedeh52), Duda et al. (Reference Duda, Jumah and Hill48), Caradas et al. (Reference Caradas, Lambert and Charlton53) and Rguibi and Belahsen(Reference Rguibi and Belahsen8) (see online Supplemental Material 3). We extracted the BMI categories preferred by participants, defined from the ideal body size mean and its sd measured with the body image scales.

Studies that measured ideal body size using a questionnaire were summarised narratively. The second (i.e. body size self-assessment) and third (i.e. body size self-satisfaction) dimensions of body image were also summarised narratively.

To identify factors influencing body size preferences quantitatively, we summarised the associations between a given factor and the outcome (i.e. either a preference for a slim(mer) or a large(r) body size).

Phase 2: Summarising qualitatively factors influencing body size preferences

Thematic synthesis was used to summarise qualitative studies(Reference Thomas and Harden54,Reference Barnett-Page and Thomas55) . Themes, defined as concepts that occurred frequently across more than one article, were identified from the analysis of the extracted text.

Phase 3: Connecting the quantitative and qualitative phases

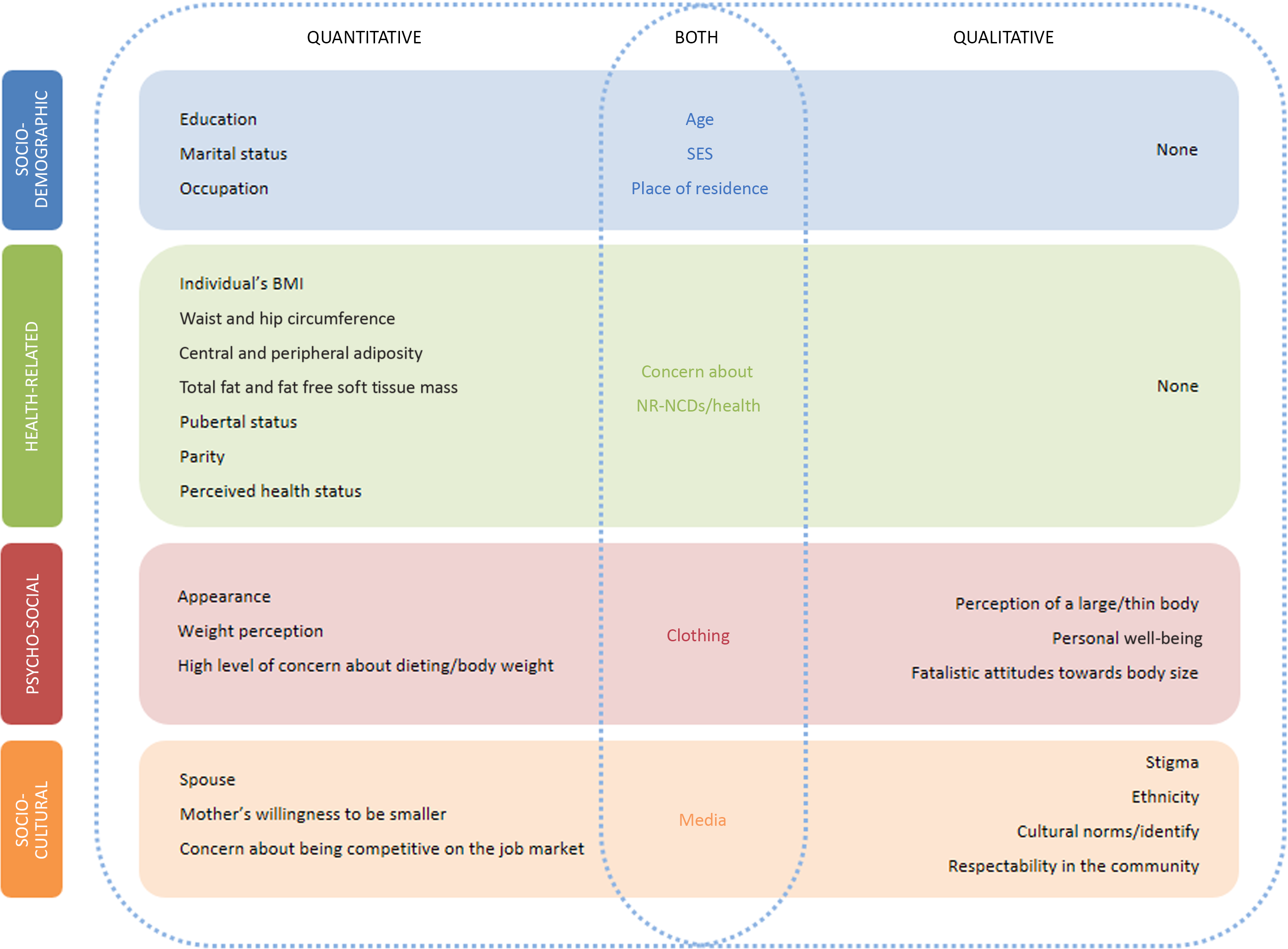

Summative content analysis(Reference Hsieh and Shannon56) from quantitative data was integrated into qualitative data synthesis. Factors identified from the quantitative and qualitative synthesis were grouped under four main overarching categories: socio-demographic, health-related, psycho-social and socio-cultural. These categories were defined based on the findings that emerged.

Phase 4: Generating an integrated map of the factors influencing body size preferences

Evidence from all studies was summarised in a map with factors split into the four categories described above.

Results

Description of studies

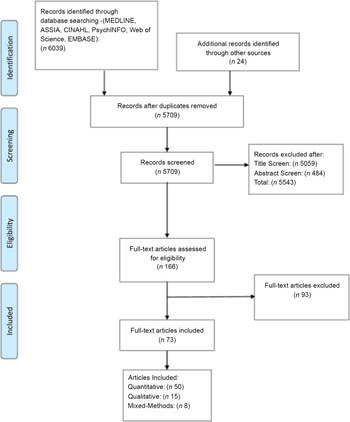

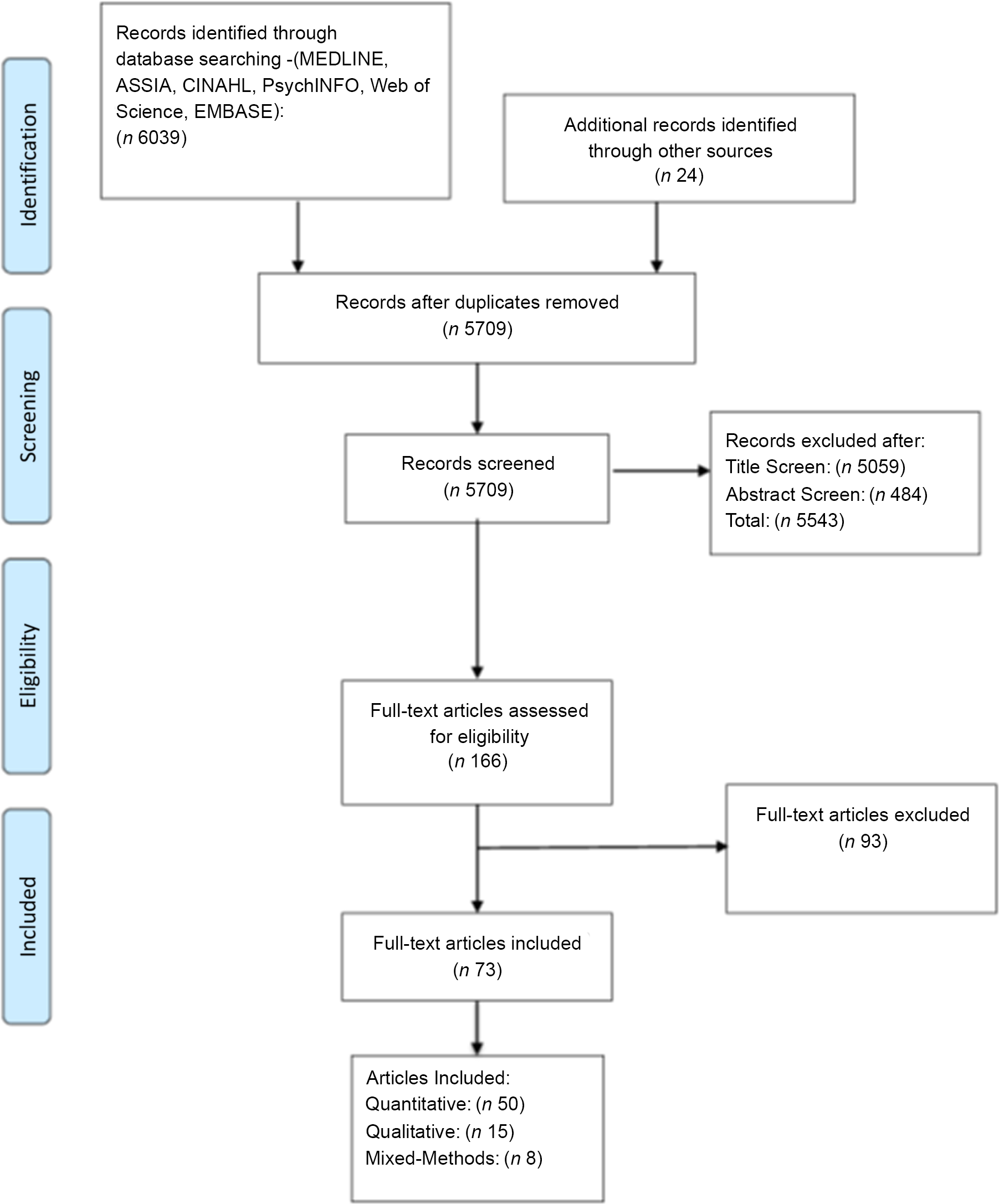

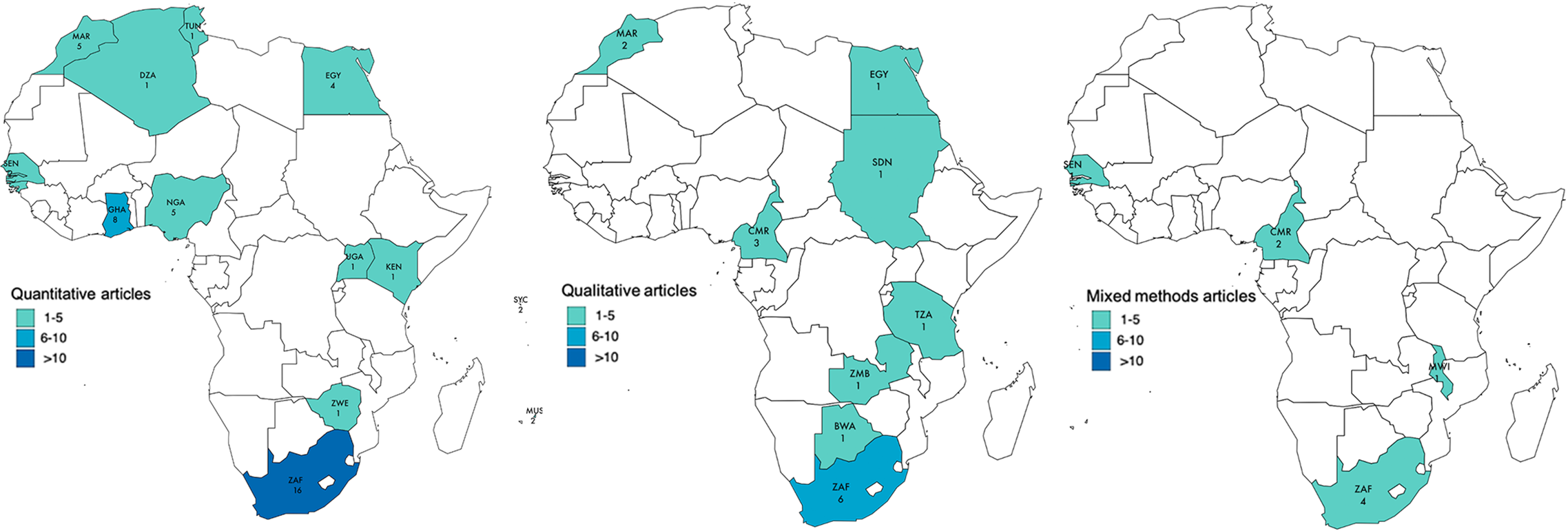

Seventy three articles were included (Fig. 2 (Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff57)). Studies were conducted in 21/54 African countries and clustered particularly within three regions: Southern Africa, West Africa and East Africa, with a predominance in South Africa (Fig. 3). More studies took place in urban (n 51) than rural (n 7) settings; and 15 studies included data from both settings.

Fig. 2 Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flow diagram showing the selection of studies for the present systematic mixed-methods review

Fig. 3 Map displaying the African countries included in the review

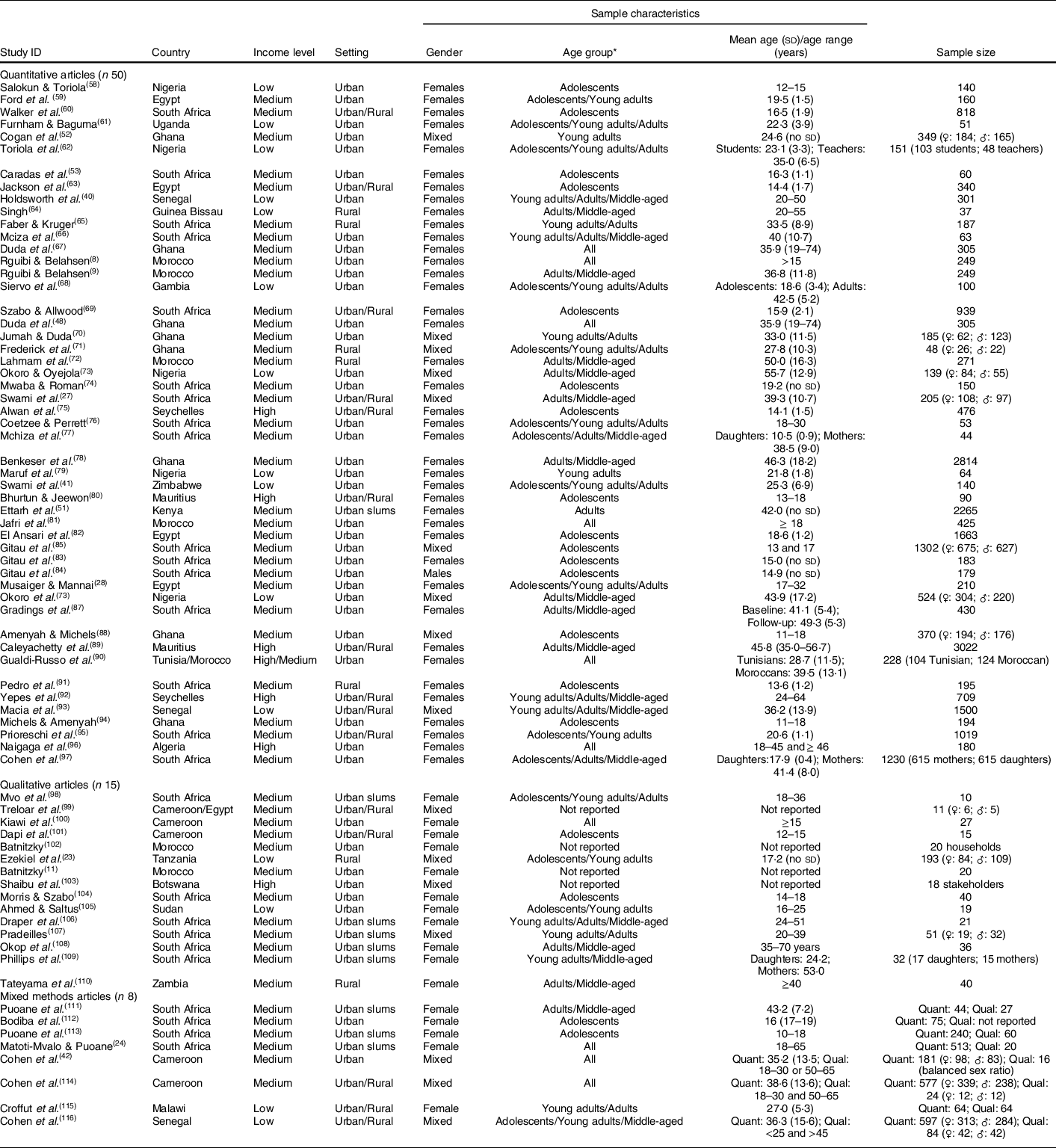

Of the seventy-three articles, fifty were quantitative(Reference Rguibi and Belahsen8,Reference Rguibi and Belahsen9,Reference Swami, Frederick and Aavik27,Reference Musaiger and Al-Mannai28,Reference Holdsworth, Gartner and Landais40,Reference Swami, Mada and Tovée41,Reference Duda, Jumah and Hill48,Reference Ettarh, Van de Vijver and Oti51–Reference Caradas, Lambert and Charlton53,Reference Salokun and Toriola58–Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Micklesfield97) , fifteen were qualitative(Reference Batnitzky11,Reference Ezekiel, Talle and Juma23,Reference Mvo, Dick and Steyn98–Reference Tateyama, Musumari and Techasrivichien110) and eight mixed methods(Reference Matoti-Mvalo and Puoane24,Reference Cohen, Boetsch and Palstra42,Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro111–Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Ndao116) (Table 2). All quantitative studies utilised a cross-sectional design, with the exception of one longitudinal design(Reference Gradidge, Norris and Micklesfield87). A total of 25 512 females and 2090 males aged ≥10 years from 17 African countries were included. Twenty-three qualitative studies from ten countries were included. Data from 828 participants and twenty households aged 10–70 years were synthesised (sample sizes between 10 and 193). Samples across studies were diverse in terms of age, SES, ethnicity, education and BMI.

Table 2 Description of included studies

♀: females; ♂: males.

* Age group: adolescents: 10–19; young adults: 20–25; adults: 25–44 and middle-aged: 45+.

Quality appraisal

The quality assessment (see online Supplemental Material 4) revealed that quantitative and qualitative studies separately scored highly on criteria such as question/objective sufficiently described, evident and appropriate study design and conclusions. Quantitative studies scored highly on well-defined outcome measures; however, some studies reported poorly on subject selection and characteristics, estimate of variance and control for confounding. Similarly, in almost all qualitative studies, authors failed to show reflexivity and/or to report verification of the procedure to establish credibility.

Data synthesis

Body size preferences for African women and adolescent girls

Dimension one: ideal body size

The majority of quantitative and mixed methods studies (46/58 (79·3 %)) assessed African women’s body size ideals (see online Supplemental Material 5). Most studies used body image scales whilst the remaining studies used questionnaires to capture the relationship between specific attributes (e.g. healthy, wealthy, dignified, respected) and different body sizes.

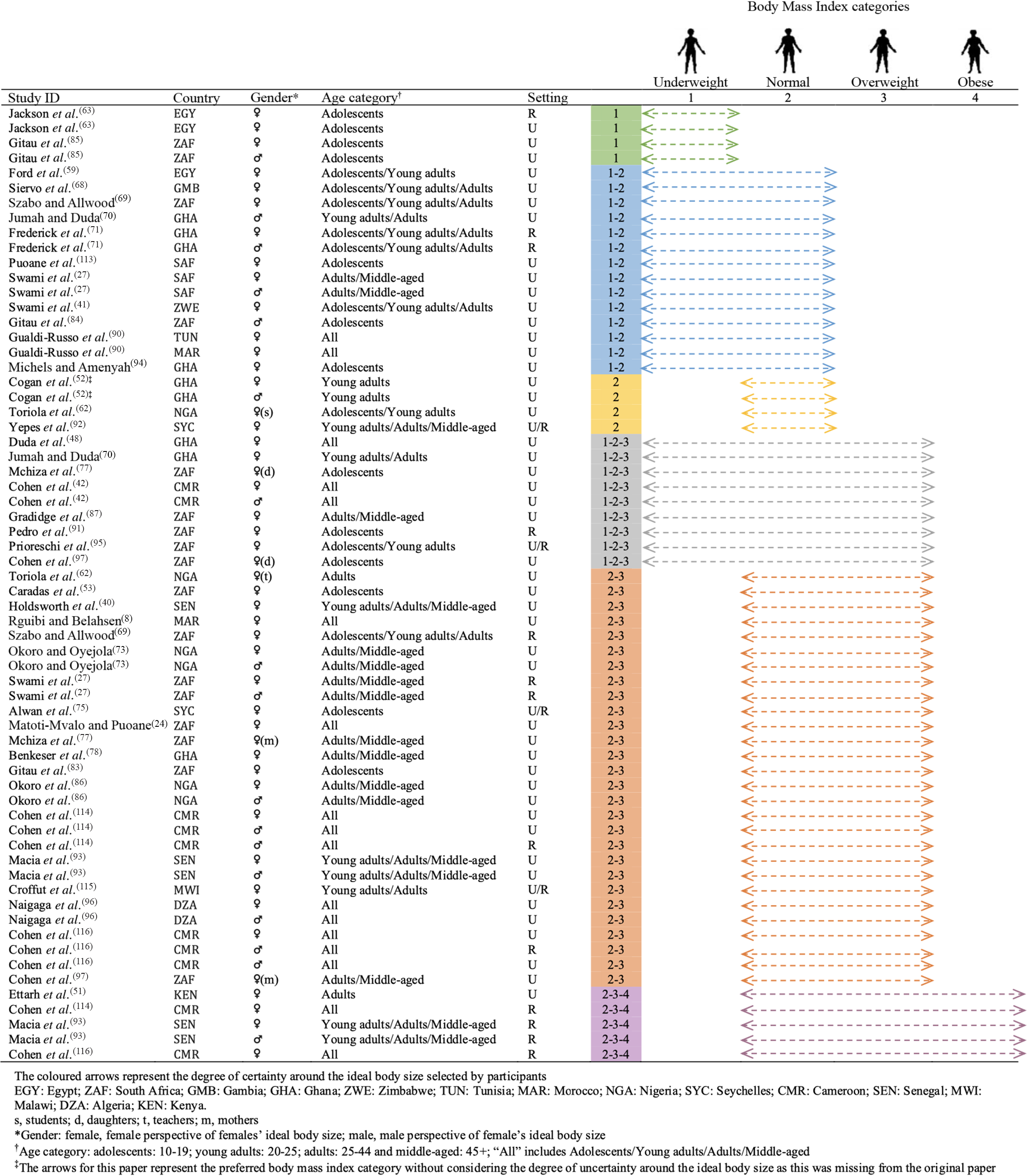

For studies using body image scales and for which a BMI category could be extracted, we found that, overall, participants in most studies preferred normal weight to overweight (Fig. 4). We observed a positive relationship between age category and ideal body size, with valorisation of underweight in some adolescent females(Reference Jackson, Rashed and Saad-Eldin63,Reference Gitau, Micklesfield and Pettifor85) and valorisation of overweight in middle-aged women(Reference Swami, Frederick and Aavik27,Reference Okoro and Oyejola73,Reference McHiza, Goedecke and Lambert77,Reference Benkeser, Biritwum and Hill78,Reference Okoro, Oyejola and Etebu86,Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Micklesfield97) . The rural–urban comparison showed that the ideal BMI category was higher in rural than urban areas in South Africa(Reference Swami, Frederick and Aavik27,Reference Szabo and Allwood69) , Senegal(Reference Macia, Cohen and Gueye93,Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Ndao116) and Cameroon(Reference Cohen, Amougou and Ponty114).

Fig. 4 Body size ideals for African women and adolescent girls

Few studies explored attributes associated with different body sizes. One study(Reference Mciza, Goedecke and Steyn66) observed differences between urban black and white South African women, especially in middle-aged women, regarding the ‘normal’ and ‘fat’ attributes; and observed that black girls and their mothers were less likely to associate ‘fatness’ with being unhappy in comparison with the white and mixed ancestry group. Likewise, another study(Reference Faber and Kruger65) found that more than 80 % of black South African rural women disagreed that ‘fat people eat more than thin people’. Moreover, 25 % of these women associated overweight with a lack of financial problems, and more women with a normal weight associated overweight/obesity with food intake, compared with those overweight and obese. In a black township of Cape Town, 74 % of black females considered that being fat ‘made you dignified’ and 43 % believed that this weight status led one to ‘feel better about yourself’(Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro111). Indeed, a woman who was overweight was perceived as ‘well-liked’ (100 %), ‘proud of her movements’ (100 %), ‘healthy’ (100 %) and ‘happy’ (94 %). However, a woman who was ‘thin’ was perceived by 33 %, 58 % and 60 % of the sample as ‘sick’, a ‘woman with worries’ and ‘not treated well by her husband’, respectively.

Dimension two: body size self-assessment

In total, 19/58 (32·7 %) studies included information on body size self-assessment (see online Supplemental Material 5). Using body image scales, one study(Reference Ettarh, Van de Vijver and Oti51) found that 34·6 % of Kenyan women living in urban Nairobi underestimated their body weight; with 28·8 % of women who underestimated their weight classified as obese, a pattern also observed in Cameroonian urban women(Reference Cohen, Boetsch and Palstra42). The same was also observed with overweight/obesity in Nigerian students and South African black urban women, as well as in black schoolgirls, Algerian Saharawi refugees, urban Tunisian, Moroccan and Malawian women(Reference Matoti-Mvalo and Puoane24,Reference Caradas, Lambert and Charlton53,Reference Maruf, Akinpelu and Nwankwo79,Reference Gradidge, Norris and Micklesfield87,Reference Gualdi-Russo, Rinaldo and Khyatti90,Reference Naigaga, Jahanlu and Claudius96,Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Micklesfield97,Reference Croffut, Hamela and Mofolo115) . Only 37·1 % of Ghanaian women living in Accra perceived their current body size as overweight or obese, even though 49·9 % were in these weight categories(Reference Jumah and Duda70), a pattern also observed by others in the same city(Reference Duda, Jumah and Hill48,Reference Benkeser, Biritwum and Hill78) .

Using questionnaire items in rural Morocco, almost all (99·2 %) women who were overweight/obese underestimated their body weight status, which increased with age(Reference Lahmam, Baali and Hilali72). Similarly, 89 % of middle-aged South African black women living in Cape Town were happy with their weight, whereas most of them were overweight or obese(Reference Mciza, Goedecke and Steyn66). Likewise, approximately two-thirds of Black women with overweight/obesity in Cape Town did not perceive themselves as such(Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro111). Finally, in urban Cameroon, 37·5 % of women considering themselves normal weight were overweight or obese(Reference Cohen, Boetsch and Palstra42).

Using body image scales, most adolescent Egyptian schoolgirls estimated their body weight accurately along the spectrum of BMI categories(Reference Jackson, Rashed and Saad-Eldin63). Similarly, in the Seychelles, 24 % of adolescent girls of normal weight considered themselves overweight,(Reference Alwan, Viswanathan and Paccaud75) and in Mauritius most adolescent girls who classified themselves as overweight were in fact normal weight(Reference Bhurtun and Jeewon80).

Dimension three: body size self-satisfaction

Overall, 44/58 (75·9 %) studies included information on body size self-satisfaction (see online Supplemental Material 5).

Of the studies that assessed satisfaction using scales (n 24), seventeen found a positive Feel minus Ideal Discrepancy (FID) (i.e. current > ideal), meaning that women and/or adolescent girls wanted to lose weight(Reference Swami, Frederick and Aavik27,Reference Cohen, Boetsch and Palstra42,Reference Duda, Jumah and Hill48,Reference Caradas, Lambert and Charlton53,Reference Ford, Dolan and Evans59,Reference Mciza, Goedecke and Steyn66,Reference Szabo and Allwood69,Reference Frederick, Forbes and Berezovskaya71,Reference Okoro and Oyejola73,Reference Maruf, Akinpelu and Nwankwo79,Reference Gradidge, Norris and Micklesfield87,Reference Gualdi-Russo, Rinaldo and Khyatti90,Reference Pedro, Micklesfield and Kahn91,Reference Prioreschi, Wrottesley and Cohen95,Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Micklesfield97,Reference Cohen, Amougou and Ponty114,Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Ndao116) . A further five studies found a negative FID (i.e. current < ideal), meaning that women and or/adolescent girls wanted to gain weight(Reference Swami, Mada and Tovée41,Reference Cogan, Bhalla and Sefa-Dedeh52,Reference Toriola, Dolan and Evans62,Reference Okoro, Oyejola and Etebu86,Reference Croffut, Hamela and Mofolo115) and two found mixed results. The two studies reporting mixed results included Mchiza et al. (Reference McHiza, Goedecke and Lambert77) with a positive FID among mothers and null FID (i.e. satisfied with current weight) among black girls, and Siervo et al. (Reference Siervo, Grey and Nyan68) with a positive FID among middle-aged women and a negative FID among young women.

Of the studies that assessed satisfaction using questionnaires (n 30), ten found that women who were overweight or obese were satisfied with their current body size(Reference Rguibi and Belahsen8,Reference Holdsworth, Gartner and Landais40,Reference Ettarh, Van de Vijver and Oti51,Reference Walker, Walker and Locke60,Reference Faber and Kruger65,Reference Alwan, Viswanathan and Paccaud75,Reference Benkeser, Biritwum and Hill78,Reference Bhurtun and Jeewon80,Reference Amenyah and Michels88,Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Micklesfield97) . The percentage of participants with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 who were satisfied with their current weight ranged from 10·5 % (obese women only)(Reference Holdsworth, Gartner and Landais40) to 95·0 % (overweight women only)(Reference Faber and Kruger65). For all papers reporting prevalence of body satisfaction among women who were overweight or obese separately, we found that the percentage of satisfaction was higher among women who were overweight, indicating that they were overall more satisfied with their body size in comparison with women who were obese(Reference Rguibi and Belahsen8,Reference Holdsworth, Gartner and Landais40,Reference Ettarh, Van de Vijver and Oti51,Reference Faber and Kruger65,Reference Benkeser, Biritwum and Hill78) . One study conducted in South Africa(Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Micklesfield97) found that the level of body satisfaction was slightly higher among mothers (28·0 %) when compared with their daughters (23·1 %) (both had a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2), and another study in South Africa(Reference Walker, Walker and Locke60) showed that body satisfaction was higher among women who were overweight or obese in rural areas (61·4 %) compared with those in urban areas (32·3 %). Eleven studies reported information on the proportion of participants with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 wanting to be larger(Reference Rguibi and Belahsen8,Reference Holdsworth, Gartner and Landais40,Reference Ettarh, Van de Vijver and Oti51,Reference Faber and Kruger65,Reference Lahmam, Baali and Hilali72,Reference Alwan, Viswanathan and Paccaud75,Reference Benkeser, Biritwum and Hill78,Reference Bhurtun and Jeewon80,Reference Amenyah and Michels88,Reference Naigaga, Jahanlu and Claudius96,Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Micklesfield97) . We found that this phenomenon ranged from none in the Seychelles(Reference Alwan, Viswanathan and Paccaud75), Mauritius(Reference Bhurtun and Jeewon80) and Algeria(Reference Naigaga, Jahanlu and Claudius96) to 45·5 % in Morocco(Reference Lahmam, Baali and Hilali72).

Of the studies that assessed satisfaction using questionnaires (n 30), eight found underweight participants (BMI < 18·5 kg/m2) were satisfied with their current body weight(Reference Rguibi and Belahsen8,Reference Holdsworth, Gartner and Landais40,Reference Ettarh, Van de Vijver and Oti51,Reference Walker, Walker and Locke60,Reference Benkeser, Biritwum and Hill78,Reference Bhurtun and Jeewon80,Reference Amenyah and Michels88,Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Micklesfield97) . The proportion of participants satisfied ranged from 2·3 % amongst women in urban Ghana(Reference Benkeser, Biritwum and Hill78) to 95·5 % amongst adolescent girls in rural South Africa(Reference Walker, Walker and Locke60). A study comparing body satisfaction among mothers and daughters who had a BMI < 18·5 kg/m2 showed that daughters were more satisfied with their body size (45·9 %) in comparison with mothers (22·2 %), meaning that younger generations might have a preference for slimmer bodies(Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Micklesfield97). Six studies reported information on the proportion of participants with a BMI < 18·5 kg/m2 willing to lose weight(Reference Rguibi and Belahsen8,Reference Rguibi and Belahsen9,Reference Holdsworth, Gartner and Landais40,Reference Benkeser, Biritwum and Hill78,Reference Bhurtun and Jeewon80,Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Micklesfield97) . We found that the prevalence of women who were underweight and wanted to be slimmer ranged from none in Morocco(Reference Rguibi and Belahsen8,Reference Rguibi and Belahsen9) to 33·3 % in Mauritius(Reference Bhurtun and Jeewon80).

Factors influencing body size preferences: quantitative and qualitative evidence

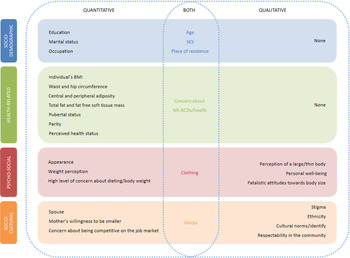

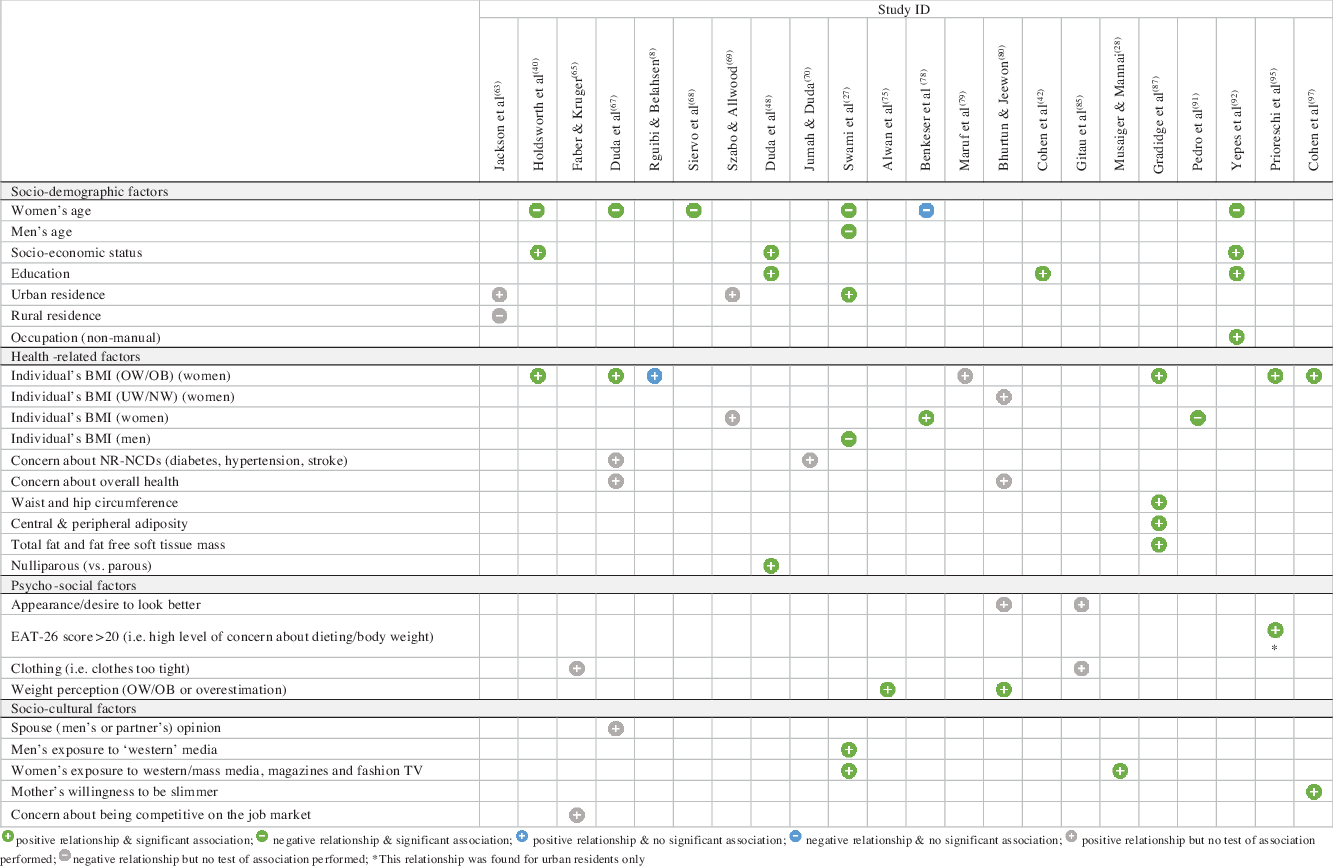

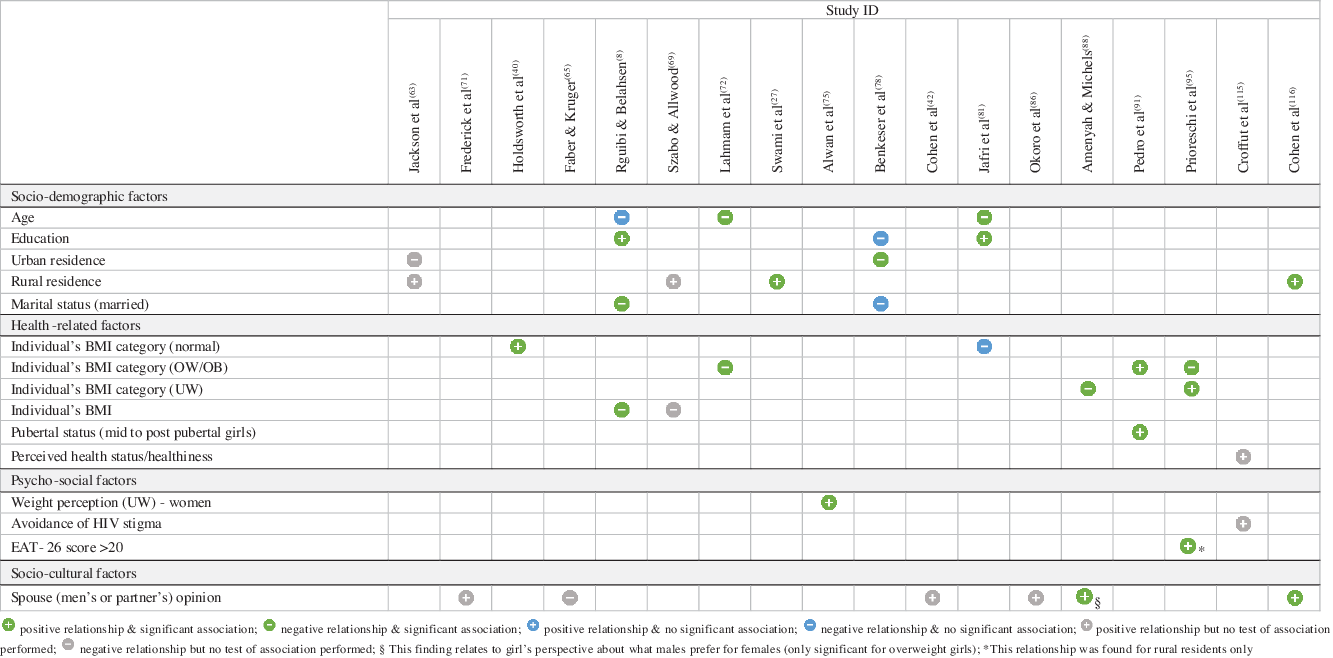

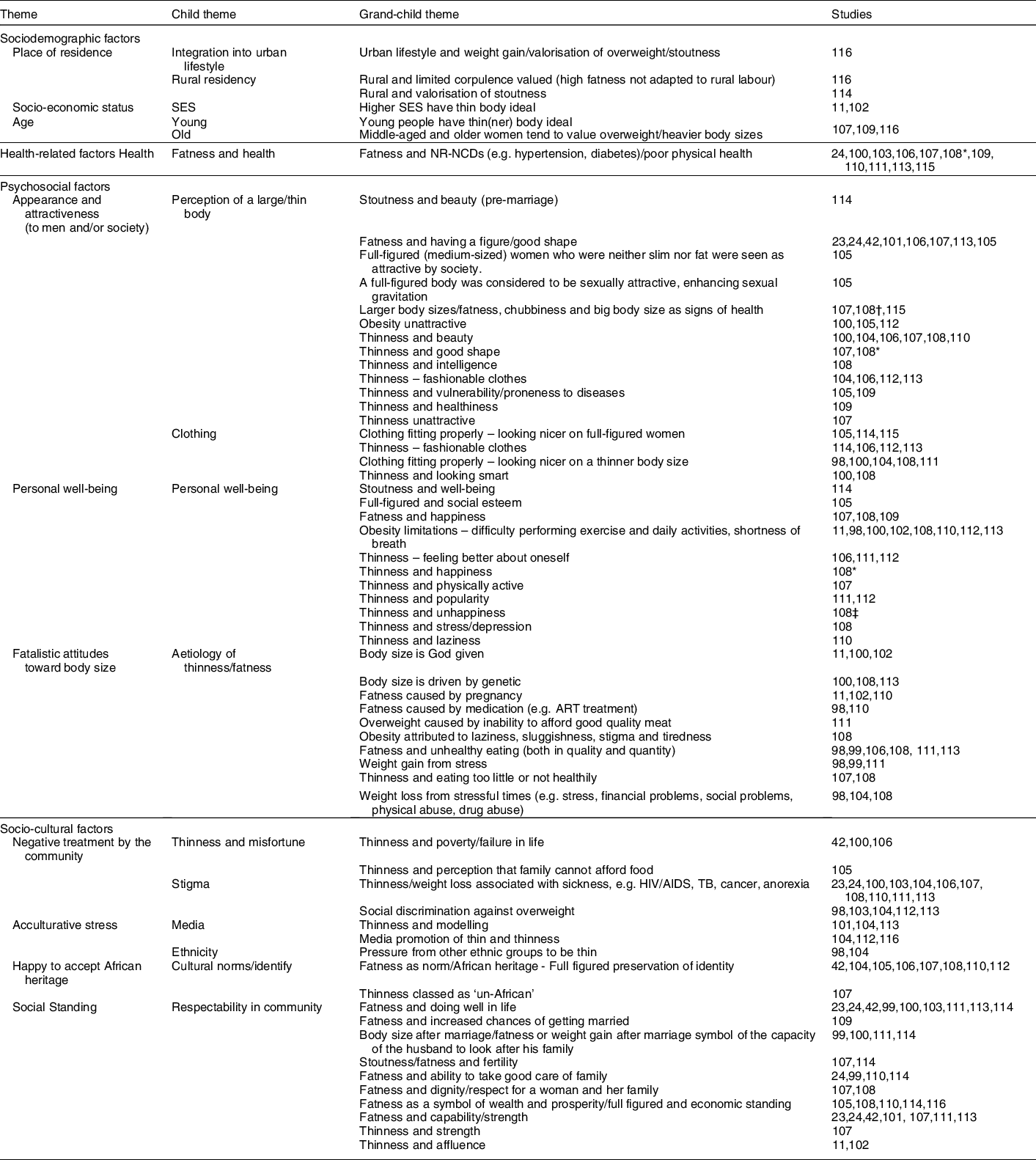

Twenty-nine quantitative studies and twenty-three qualitative studies (including eight mixed-methods studies) reported factors associated with body size preferences (see online Supplemental Material 5). For both types of studies, factors were grouped into four overarching themes (socio-demographic, health-related, psycho-social and socio-cultural), and their influence on preferred body size (i.e. preference for a slim(mer) or a large(r) body size) indicated (Tables 3 and 4). Eleven analytical themes emerged from qualitative studies (Table 5). The integrated results are discussed below and summarised in Fig. 5.

Table 3 Factors associated with a preference for a slim(mer) body size among African women and adolescent girls from the quantitative evidence synthesis

Table 4 Factors associated with a preference for a large(r) body size among African women and adolescent girls from the quantitative evidence synthesis

Table 5 Factors influencing body size preferences for African women and adolescent girls from the qualitative evidence synthesis

* Found for normal weight women only.

† Found in overweight/obese women.

‡ Found in obese women.

Fig. 5 Integrated map of the factors influencing body size preferences for African women and adolescent girls

Socio-demographic factors

The quantitative evidence showed that increased SES(Reference Holdsworth, Gartner and Landais40,Reference Duda, Jumah and Hill48,Reference Yepes, Maurer and Stringhini92) , non-manual occupations(Reference Yepes, Maurer and Stringhini92) and living in urban areas(Reference Swami, Frederick and Aavik27,Reference Jackson, Rashed and Saad-Eldin63,Reference Szabo and Allwood69) were associated with slimmer body size preferences. Rural residency was associated with a greater preference for a larger body size,(Reference Swami, Frederick and Aavik27,Reference Jackson, Rashed and Saad-Eldin63,Reference Szabo and Allwood69,Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Ndao116) whilst marriage was associated with a lower preference for a larger body size(Reference Rguibi and Belahsen8,Reference Benkeser, Biritwum and Hill78) . Younger participants had a greater preference for slimmer body sizes in Senegal(Reference Holdsworth, Gartner and Landais40), Ghana(Reference Duda, Jumah and Hill67,Reference Benkeser, Biritwum and Hill78) , Gambia(Reference Siervo, Grey and Nyan68), South Africa(Reference Swami, Frederick and Aavik27) and the Seychelles(Reference Yepes, Maurer and Stringhini92), but a greater preference for a larger body size in three studies conducted in Morocco(Reference Rguibi and Belahsen8,Reference Lahmam, Baali and Hilali72,Reference Jafri, Jabari and Dahhak81) . Increased years of formal education was associated with a greater preference for both slimmer body size ideals in Ghana(Reference Duda, Jumah and Hill48), Cameroon(Reference Swami, Mada and Tovée41) and Seychelles(Reference Yepes, Maurer and Stringhini92) and larger body size ideals in Morocco(Reference Rguibi and Belahsen8,Reference Jafri, Jabari and Dahhak81) . However, one study(Reference Benkeser, Biritwum and Hill78) in Ghana found that increased years of formal education was associated with a lower preference for larger body size but this was NS.

The qualitative evidence revealed that higher SES(Reference Batnitzky11,Reference Batnitzky102) and younger participants(Reference Pradeilles107,Reference Phillips, Comeau and Pisa109,Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Ndao116) had slimmer body size preferences. Valorisation of stoutness was found in both urban Senegal(Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Ndao116) and rural Cameroon(Reference Cohen, Amougou and Ponty114), especially in middle-aged and older women. However, high fatness was not valued by younger and also older women in rural Senegal, as it was deemed ill-adapted to rural labour and hence, not valued(Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Ndao116).

‘If you are too rey [stout] in the village, you will not be able to work or cultivate…’ (middle-aged woman, urban, Senegal)(Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Ndao116)

Health-related factors

BMI

Individual BMI was associated with body size preference, although mixed results were found.

Overall, increased BMI in women was positively associated with a greater preference for slimmer body sizes(Reference Szabo and Allwood69,Reference Benkeser, Biritwum and Hill78) , with the exception of one study(Reference Pedro, Micklesfield and Kahn91), and negatively associated with a preference for a large(r) body size(Reference Rguibi and Belahsen8,Reference Szabo and Allwood69) . One study also found a negative association between men’s individual BMI and a preference for slimmer female body sizes(Reference Swami, Frederick and Aavik27).

Women who were overweight or obese had a predominantly greater preference for a slimmer body size(Reference Rguibi and Belahsen8,Reference Holdsworth, Gartner and Landais40,Reference Duda, Jumah and Hill67,Reference Maruf, Akinpelu and Nwankwo79,Reference Gradidge, Norris and Micklesfield87,Reference Prioreschi, Wrottesley and Cohen95,Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Micklesfield97) . Similarly, a greater waist and hip circumference, central and peripheral adiposity and total fat and fat free soft tissue mass were positively associated with slimmer body size preferences or participants desire for weight loss(Reference Gradidge, Norris and Micklesfield87). Being overweight or obese was also significantly associated with a lower preference for a larger body size(Reference Lahmam, Baali and Hilali72,Reference Prioreschi, Wrottesley and Cohen95) , with the exception of one study in South Africa, for which the association was positive(Reference Pedro, Micklesfield and Kahn91).

Women who were underweight or normal weight had either a greater preference for a slimmer body size/lower preference for a larger body size(Reference Bhurtun and Jeewon80,Reference Jafri, Jabari and Dahhak81,Reference Amenyah and Michels88) or a greater preference for a large(r) body size(Reference Holdsworth, Gartner and Landais40,Reference Prioreschi, Wrottesley and Cohen95) .

Concern about health

Two quantitative studies found that participants who reported being concerned about their overall health status or the possibility of developing nutrition-related noncommunicable diseases had a greater preference for a slimmer body size(Reference Duda, Jumah and Hill67,Reference Jumah and Duda70) . The relationship between overweight/fatness and nutrition-related noncommunicable diseases was reported in eleven qualitative studies(Reference Matoti-Mvalo and Puoane24,Reference Kiawi, Edwards and Shu100,Reference Shaibu, Holsten and Stettler103,Reference Draper, Davidowitz and Goedecke106–Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro111,Reference Puoane, Lungiswa and Steyn113,Reference Croffut, Hamela and Mofolo115) . As a result, some participants wanted to lose weight for health reasons.

‘I heard that when a person is fat there are a lot of fats and oils in the body, which may result in some diseases, like hypertension and diabetes’…’I would like to have medium [overweight] body, because sometimes when you are too fat, it becomes difficult to walk’ (adult women, urban/rural, Malawi)(Reference Croffut, Hamela and Mofolo115)

Biological factors

Being nulliparous(Reference Duda, Jumah and Hill48) was associated with a greater preference for a slimmer body size whilst pubertal status (i.e. mid to post-pubertal girls)(Reference Pedro, Micklesfield and Kahn91) was associated with a preference for a larger body size.

Psycho-social factors

Appearance and attractiveness

Quantitative studies reported a positive association between appearance or a desire to look better and a preference for a slimmer body size(Reference Bhurtun and Jeewon80,Reference El Ansari, Dibba and Labeeb82) . Likewise, clothing (i.e. clothes too tight) was positively associated with a desire for a slimmer body size(Reference Szabo and Allwood69,Reference Gitau, Micklesfield and Pettifor83) .

Appearance and attractiveness to men and/or society was a theme that emerged in most of the qualitative studies. An important aspect of appearance was the way clothing fell on different body sizes. Participants were motivated to lose weight to fit into their old clothes, to look smart or because they felt that clothes on thinner body sizes looked nicer(Reference Mvo, Dick and Steyn98,Reference Kiawi, Edwards and Shu100,Reference Morris and Szabo104,Reference Okop, Mukumbang and Mathole108,Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro111) .

‘Being overweight does not look nice, people often think that you are pregnant’… ‘Bigger clothes are more expensive and less pretty’ (adult/middle-aged women, urban, South Africa)(Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro111)

Four studies reported that fashionable clothes only came in smaller sizes and would therefore only fit slim people(Reference Morris and Szabo104,Reference Draper, Davidowitz and Goedecke106,Reference Bodiba, Madu and Ezeokana112,Reference Puoane, Lungiswa and Steyn113) . However, the importance of filling out clothes to showcase one’s figure was also reported in three studies(Reference Ahmed and Saltus105,Reference Cohen, Amougou and Ponty114,Reference Croffut, Hamela and Mofolo115) .

Body size was associated with physical attractiveness, which in turn equated to a better chance of ‘getting a boyfriend or husband’. In six studies, thinness was associated with beauty and good shape(Reference Kiawi, Edwards and Shu100,Reference Morris and Szabo104,Reference Draper, Davidowitz and Goedecke106–Reference Okop, Mukumbang and Mathole108,Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro111) , and three studies reported ‘fatness’ as unattractive and diminishing one’s chances of securing a boyfriend/husband(Reference Kiawi, Edwards and Shu100,Reference Ahmed and Saltus105,Reference Bodiba, Madu and Ezeokana112) . On the other hand, one study associated stoutness with beauty in women pre-marriage(Reference Cohen, Amougou and Ponty114) and seven studies associated ‘being fat’, particularly having large hips, with ‘having a figure’ or a ‘good shape’(Reference Ezekiel, Talle and Juma23,Reference Matoti-Mvalo and Puoane24,Reference Swami, Mada and Tovée41,Reference Dapi, Omoloko and Janlert101,Reference Draper, Davidowitz and Goedecke106,Reference Pradeilles107,Reference Puoane, Lungiswa and Steyn113) .

‘Our culture says that we are supposed to be fat. You must have structure, you must be beautiful. In other words, our culture does not allow women to be thin. They say that someone who is fat is sexier’. (adult/middle-aged woman, urban, South Africa)(Reference Draper, Davidowitz and Goedecke106)

To have a good figure, it was seen as important that women gained weight proportionally and did not get too fat(Reference Cohen, Boetsch and Palstra42). It was seen as particularly important that women were not physically restricted by their body size, otherwise their fatness shifted into the realm of being perceived as a result of greed or laziness. In another study, full-figured women (defined as women of a ‘medium size’, neither slim nor fat by investigators) were seen as attractive by society and were considered to be sexually attractive, enhancing sexual gravitation(Reference Ahmed and Saltus105). Body size was also associated with intelligence (thin women were perceived as smart)(Reference Okop, Mukumbang and Mathole108) and health, but the evidence was mixed for the latter. In two studies, we found that thinness was associated with good health(Reference Ahmed and Saltus105,Reference Phillips, Comeau and Pisa109) whilst in three other studies, we found that being overweight was a sign of perceived good health(Reference Pradeilles107,Reference Okop, Mukumbang and Mathole108,Reference Croffut, Hamela and Mofolo115) .

Body size perception

An overestimation of body size or perception of self as overweight/obese was significantly associated with a preference for a slimmer body size(Reference Alwan, Viswanathan and Paccaud75,Reference Bhurtun and Jeewon80) , whereas women who perceived themselves as underweight had a greater preference for a larger body size(Reference Alwan, Viswanathan and Paccaud75). In one study(Reference Prioreschi, Wrottesley and Cohen95), an EAT-26 score >20, which indicates a high level of concern about dieting, body weight or problematic eating behaviours, was associated with either a greater preference for a slimmer body size (urban residents) or larger body size (rural residents).

Avoidance of HIV stigma

One quantitative study found a positive association between avoiding HIV stigma and a preference for a large(r) body size(Reference Croffut, Hamela and Mofolo115).

Personal well-being

Perceptions attached to body size and personal well-being were discussed by participants in most of the qualitative studies. In five studies, fatness or a full-figured body size was associated with well-being(Reference Cohen, Amougou and Ponty114), social esteem(Reference Ahmed and Saltus105) and happiness(Reference Pradeilles107–Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro111).

‘If a person is fat [overweight], we usually assume she is happy and has a lot of money. It’s evident that he/she eats nicely’ (middle-aged woman, urban, South Africa)(Reference Okop, Mukumbang and Mathole108)

However, the difficulties associated with obesity (i.e. difficulty performing exercise and daily activities and shortness of breath) were also highlighted(Reference Batnitzky11,Reference Mvo, Dick and Steyn98,Reference Kiawi, Edwards and Shu100,Reference Batnitzky102,Reference Okop, Mukumbang and Mathole108,Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro111–Reference Puoane, Lungiswa and Steyn113) .

‘I think there is nothing good about being fat because you are constantly sick, and you constantly have pains’ (adolescent girl, urban, South Africa)(Reference Puoane, Lungiswa and Steyn113)

The results on thinness were mixed with studies highlighting an association between thinness and markers of personal well-being, such as self-esteem(Reference Draper, Davidowitz and Goedecke106,Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro111,Reference Bodiba, Madu and Ezeokana112) , happiness(Reference Okop, Mukumbang and Mathole108), being physically active(Reference Pradeilles107) and popularity(Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro111,Reference Bodiba, Madu and Ezeokana112) and other studies providing evidence of an association between thinness and unhappiness(Reference Okop, Mukumbang and Mathole108), stress/depression(Reference Okop, Mukumbang and Mathole108) and laziness(Reference Tateyama, Musumari and Techasrivichien110).

Fatalistic attitudes towards body size

Various reasons were proposed as ‘causing’ obesity, many of which are founded in scientific evidence, ranging from unhealthy eating in terms of quantity and quality(Reference Mvo, Dick and Steyn98,Reference Treloar, Porteous and Hassan99,Reference Draper, Davidowitz and Goedecke106,Reference Okop, Mukumbang and Mathole108,Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro111,Reference Puoane, Lungiswa and Steyn113) , stress(Reference Mvo, Dick and Steyn98,Reference Treloar, Porteous and Hassan99,Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro111) , medication (e.g. anti-retroviral treatment)(Reference Mvo, Dick and Steyn98,Reference Tateyama, Musumari and Techasrivichien110) , genetics(Reference Kiawi, Edwards and Shu100,Reference Okop, Mukumbang and Mathole108,Reference Puoane, Lungiswa and Steyn113) , pregnancy(Reference Batnitzky11,Reference Batnitzky102,Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro111) and laziness(Reference Okop, Mukumbang and Mathole108).

‘There are people who are born fat even though they try to lose weight’ (adolescent girl, urban, South Africa)(Reference Puoane, Lungiswa and Steyn113)

However, the belief that obesity was ‘God-given’ also emerged(Reference Batnitzky11,Reference Kiawi, Edwards and Shu100,Reference Batnitzky102) :

‘I used to be thin before I had children. Then slowly after each child I became bigger. This is what Allah intends for a mother to look like’ (woman, urban, Morocco)(Reference Batnitzky11)

This fatalistic belief can lead to participants accepting their body size and being less motivated to lose weight(Reference Batnitzky11,Reference Kiawi, Edwards and Shu100) . Factors influencing thinness included stress(Reference Mvo, Dick and Steyn98,Reference Morris and Szabo104,Reference Okop, Mukumbang and Mathole108) and eating too little(Reference Pradeilles107,Reference Okop, Mukumbang and Mathole108) .

Socio-cultural factors

Family influence

From the quantitative evidence, males’ or husbands’ opinions(Reference Cohen, Boetsch and Palstra42,Reference Faber and Kruger65,Reference Duda, Jumah and Hill67,Reference Frederick, Forbes and Berezovskaya71,Reference Okoro, Oyejola and Etebu86,Reference Amenyah and Michels88,Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Ndao116) and mothers’ opinions(Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Micklesfield97) influenced women’s body size preferences. This was a positive influence for a preference for a slimmer body and mixed for a preference for a large(r) body size.

Negative treatment by the community

Thinness and/or weight loss were associated with misfortune in four studies. A person who was thin was seen as being too poor to afford food, or having failed in life(Reference Cohen, Boetsch and Palstra42,Reference Kiawi, Edwards and Shu100,Reference Ahmed and Saltus105,Reference Draper, Davidowitz and Goedecke106) .

‘My parents also put pressure on me, always commenting on my weight and why I look so thin. They think that being thin is a stigma as people might think that the family cannot afford to buy food’ (adolescent girl, urban, Sudan)(Reference Ahmed and Saltus105)

Activities associated with trying to lose weight, such as walking, were also associated with poverty(Reference Kiawi, Edwards and Shu100,Reference Draper, Davidowitz and Goedecke106) .

Being thin or losing weight was also strongly associated with illness, particularly with HIV and/or TB(Reference Ezekiel, Talle and Juma23,Reference Matoti-Mvalo and Puoane24,Reference Kiawi, Edwards and Shu100,Reference Shaibu, Holsten and Stettler103,Reference Morris and Szabo104,Reference Draper, Davidowitz and Goedecke106–Reference Okop, Mukumbang and Mathole108,Reference Tateyama, Musumari and Techasrivichien110,Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro111,Reference Puoane, Lungiswa and Steyn113) . Participants preferred not to embody these factors – poverty, HIV and TB – as they are associated with being gossiped about and shunned. Even participants who were aware of the health risks of being overweight and acknowledged that it was impossible to tell if someone has HIV just from their body size still preferred to gain weight or remain overweight to avoid being ostracised(Reference Draper, Davidowitz and Goedecke106).

‘She would not be happy [to lose weight] because in our community it would be perceived that there is something wrong with her. She would think that the community is looking at her, so she would feel insecure. They would judge her because they say the person is sick and now wants to cover it up by dieting and exercise’ (adult/middle-aged woman, urban, South Africa) (Reference Draper, Davidowitz and Goedecke106)

However, five studies, mainly involving secondary school pupils, reported bullying and exclusion of individuals who were overweight(Reference Mvo, Dick and Steyn98,Reference Shaibu, Holsten and Stettler103,Reference Morris and Szabo104,Reference Bodiba, Madu and Ezeokana112,Reference Puoane, Lungiswa and Steyn113) .

Cultural norms, identity and acculturative stress

Two quantitative studies provided evidence for a positive association between exposure to media and a preference for a slimmer body size(Reference Swami, Frederick and Aavik27,Reference Musaiger and Al-Mannai28) . One Egyptian study(Reference Musaiger and Al-Mannai28) found that the risk that pictures in female magazines would influence girls’ ideas of a perfect body shape was almost three times higher among female students who were exposed to magazines v. not or less frequently exposed. An association between television exposure and female students’ ideas of a perfect body shape was also observed.

If having a large body size was seen as a traditional African ideal or heritage(Reference Cohen, Boetsch and Palstra42,Reference Morris and Szabo104,Reference Ahmed and Saltus105–Reference Okop, Mukumbang and Mathole108,Reference Tateyama, Musumari and Techasrivichien110,Reference Bodiba, Madu and Ezeokana112) , the media’s promotion of thinness was viewed as the antithesis to this tradition(Reference Morris and Szabo104,Reference Bodiba, Madu and Ezeokana112,Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Ndao116) . Participants reported feeling pressure and disappointment from the media’s constant promotion of the thin ideal(Reference Morris and Szabo104,Reference Bodiba, Madu and Ezeokana112) .

‘I hate the media’s emphasis on weight loss because we cannot all be the same. Some people are born thin and others fat. This emphasis makes people think that fat is unacceptable and ugly’ (adolescent girl, urban, South Africa)(Reference Bodiba, Madu and Ezeokana112)

Some participants wanted to be thin like models because they aspired to a modelling career, or because it was fashionable(Reference Dapi, Omoloko and Janlert101,Reference Morris and Szabo104,Reference Puoane, Lungiswa and Steyn113) . Only secondary school pupils reported these views. Black South African participants also reported negative comments from White and Mixed-Ancestry friends/colleagues as influencing their perceptions of body size ideals and causing insecurity in their African heritage beliefs(Reference Mvo, Dick and Steyn98,Reference Morris and Szabo104) .

Social standing

Body size was viewed as an embodiment of community respectability. Fatness in women pre-marriage was important as it increased their chances of marriage(Reference Phillips, Comeau and Pisa109). A woman who gained weight soon after marriage was viewed with pride by her in-laws and respected by the community, as her weight gain symbolised being well cared for by her husband and more capable of being fertile and caring for her family(Reference Matoti-Mvalo and Puoane24,Reference Treloar, Porteous and Hassan99,Reference Kiawi, Edwards and Shu100,Reference Pradeilles107,Reference Okop, Mukumbang and Mathole108,Reference Tateyama, Musumari and Techasrivichien110,Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro111,Reference Cohen, Amougou and Ponty114) .

‘For a woman, being overweight suggests that her husband takes good care of her, that he is comfortable, he has money’ (adult woman, urban, Cameroon)(Reference Cohen, Amougou and Ponty114)

A large body size was also associated with general capability, strength, doing well in life(Reference Ezekiel, Talle and Juma23,Reference Matoti-Mvalo and Puoane24,Reference Cohen, Boetsch and Palstra42,Reference Treloar, Porteous and Hassan99–Reference Dapi, Omoloko and Janlert101,Reference Shaibu, Holsten and Stettler103,Reference Pradeilles107,Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro111,Reference Puoane, Lungiswa and Steyn113) and also represented a symbol of wealth and prosperity(Reference Ahmed and Saltus105,Reference Okop, Mukumbang and Mathole108,Reference Tateyama, Musumari and Techasrivichien110,Reference Puoane, Lungiswa and Steyn113,Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Ndao116) . On the other hand, three studies reported that thinness was associated with affluence(Reference Batnitzky11,Reference Batnitzky102) and strength(Reference Pradeilles107).

Discussion

Summary of key findings

The evidence we synthesised on body size preferences from seventy three quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods studies in twenty-one African countries suggests that normal or overweight body sizes are mainly preferred for African females. This echoes earlier findings from authors who conducted research amongst African Americans over 20 years ago(Reference Flynn and Fitzgibbon117). This systematic review found evidence that obesity was a preferred body size in only a small number of studies (n 4), contrary to widely held assumptions concerning the African region.

We observed differences between rural and urban settings within the countries in terms of body size preferences. Furthermore, we noted that countries with the highest economic development, such as South Africa(Reference Gitau, Micklesfield and Pettifor83–Reference Gitau, Micklesfield and Pettifor85), Ghana(Reference Michels and Amenyah94) and Egypt(Reference Musaiger and Al-Mannai28,Reference Ford, Dolan and Evans59,Reference Jackson, Rashed and Saad-Eldin63,Reference El Ansari, Dibba and Labeeb82) , presented several studies showing a preference for thinness, particularly in young women.

Socio-demographic, health-related, psycho-social and socio-cultural factors were found to influence African females’ body size preferences. Factors such as age, SES, place of residence, concern about nutrition-related noncommunicable diseases, clothing and media were found to influence body size preferences in both quantitative and qualitative studies.

Younger participants in Morocco had a higher preference for larger body size whilst in West Africa (Ghana, Gambia, Senegal), East Africa (Seychelles) and Southern Africa (South Africa), they had a greater preference for slimmer body sizes. The effect of age on body size preferences may act via two main pathways. First, lay norms revealed that being overweight was associated with marital and economic status, which could represent proxies for responsibilities associated with age(Reference Batnitzky102). Indeed, age has both a biological and socio-cultural component. In traditional societies, age represents wisdom, responsibility and maturity, especially when associated with moderate overweight for married women(Reference De Garine and Pollock118). Second, young people living in urban areas are more exposed to external media and more likely to question the benefits of overweight(Reference Swami, Frederick and Aavik27,Reference Siervo, Grey and Nyan68,Reference Szabo and Allwood69,Reference Dapi, Omoloko and Janlert101) . Media exposure may influence body size preferences more in adolescent females than in adults. Although older females with a higher BMI tended to desire a slimmer body size, there was some evidence that they become desensitised over time to external media(Reference Cusumano and Thompson119), especially as they still valued overweight more, as a symbol of prosperity, fertility and peacefulness in the household(Reference Rguibi and Belahsen8,Reference Gradidge, Golele and Cohen39,Reference Cohen, Gradidge and Micklesfield97) .

Both quantitative(Reference Holdsworth, Gartner and Landais40,Reference Duda, Jumah and Hill48,Reference Yepes, Maurer and Stringhini92) and qualitative evidence(Reference Batnitzky11,Reference Batnitzky102) showed that increased SES or better employment was associated with slimmer body size preference. The effect of wealth on body size preferences may act by modulating exposure to factors such as external media, tighter ‘fashionable’ clothing, knowledge of the health risks associated with obesity and better access to food resources in urban environments.

Some themes that emerged from the qualitative synthesis corresponded well with factors reported in the quantitative studies in our review, and in a previously published qualitative review(Reference Ozodiegwu, Littleton and Nwabueze120). As part of their review, Ozodiegwu and colleagues(Reference Ozodiegwu, Littleton and Nwabueze120) explored factors in the literature that influence overweight or obesity in women of reproductive age living in four different Sub-Saharan African countries (i.e. Ghana, Kenya, South Africa and Botswana); and therefore, we present some overlapping results. Nevertheless, our mixed-methods review included papers from a broader time range (1985 to August 2019), as well as from twenty-one countries in Africa. In our study, appearance played a role in women’s satisfaction with their body size, as they wanted to look attractive to men and peers. Thinness and fatness were both associated with attractiveness, albeit in different studies. Fatness was associated with having a nice figure; a preference for larger hips was reported by African men and women is in accordance with historical observations from Africa and preferences reported by African Americans(Reference Tunaley, Walsh and Nicolson25,Reference Flynn and Fitzgibbon117,Reference Ozodiegwu, Littleton and Nwabueze120) . This preference has been explained by evolutionary theory whereby large hips are perceived as indicative of a woman’s suitability for childbearing, and therefore her attractiveness and worth within that society, as historically women’s roles equated to being a wife and mother(Reference Tunaley, Walsh and Nicolson25). Thinness, as an embodiment of beauty or looking smart, may highlight women’s changing roles in these societies, or perhaps the encroaching influence of ‘Western’ media and ideals on these traditional views(Reference Swami22). It appears these influences may be more prominent amongst younger participants, as evidenced by the fact that acculturative stress was only reported by younger women. Pressure from peers to look slimmer was also reported among adolescent girls(Reference Ozodiegwu, Littleton and Nwabueze120). The risk of nutrition-related noncommunicable diseases associated with obesity was found to influence women’s preferred body size. Knowledge of the associated health risks of obesity was not universally reported across studies. Women who were knowledgeable about health were still reluctant to lose weight to avoid the stigma associated with HIV and/or TB, as reported in a previous review(Reference Ozodiegwu, Littleton and Nwabueze120). This risk of facing ridicule also overshadowed weight loss motivations driven by the prospect of improving personal well-being. This emphasises the importance of community acceptance and social standing on African women’s autonomy. It also highlights how the power of social norms can disempower individuals who might want to manage their weight for personal or health reasons. However, it appears that the HIV and/or TB stigma associated with a phobia for thinness seems to progressively disappear in the most educated young women, while the least educated still persist in valuing stoutness, their socio-cultural environment usually linking thinness with poor healthy status, such as being HIV-positive(Reference Gitau, Micklesfield and Pettifor85). Another factor that contributed to disempowering women from managing their weight was their understanding of the aetiology of fatness/thinness. The aetiologies cited were generally viewed as being out of the individual’s control and therefore not worth trying to change.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this review is the use of a mixedmethods’ approach to review a large body of evidence. This allowed a holistic understanding of body size preferences for African women and adolescent girls and the factors driving these. Furthermore, all included studies were of medium or high quality. Even if the FRS(Reference Cohen, Boetsch and Palstra42), used in several studies, was initially developed for Caucasian populations, it was subsequently adapted to African populations(Reference Becker, Yanek and Koftman121), and a black adolescent female version was also developed and validated(Reference Mciza, Goedecke and Steyn66). These African versions of the FRS were used in some studies included in this review(Reference Okoro and Oyejola73,Reference McHiza, Goedecke and Lambert77,Reference Okoro, Oyejola and Etebu86) , showing that the FRS has been contextualised to a certain degree to assess body size perceptions of Africans. Whilst the FRS has limitations as a figural scale, its widespread use allows contextual interpretation of the findings across studies. Another strength is that the prevalence of overweight/obesity among the countries included in our study ranged from 21·3 % in Senegal to 72·0 % in Seychelles(122), which can be considered capturing a range of countries at different stages of the nutrition transition in the African continent.

Limitations of the review included generalisability to the African continent, as Africa is a large, economically and ethnically diverse continent. Most of the quantitative studies were conducted in urban settings, limiting their applicability outside urban settings. Studies were conducted in 21/54 African countries and clustered particularly within Southern Africa, West Africa and East Africa, capturing differences between traditional and modern perceptions of female body size. We noted that findings from Morocco appeared quite different from other countries in terms of body size preferences and factors influencing these. Although factors that play a role in influencing body size preferences were identified in the quantitative studies, it was not possible to establish causality, as almost all included studies were cross-sectional.

Studies included in our review were appraised for quality using the QualSyst tool, which assessed both the quality of studies and their reporting. To our knowledge, this was the most appropriate published tool for the range of study designs included in our review. However, we acknowledge the inherent limitations of such tools, which are reliant on what is reported by authors and that are also subjective in nature(Reference Verhage and Boels123). As such, there is a possibility that study quality may have been misclassified. A specific risk of bias tool may have provided a more objective measure of study quality by focusing on the actual design and conduct of a study. However, no such tool currently exists for the range of study designs included in this review. Furthermore, given the lack of consensus on the issue of excluding studies based on quality(Reference Verhage and Boels123) and evidence that shows that excluding lower quality studies does not significantly impact on the synthesis of results(Reference Carroll, Booth and Lloyd-Jones124,Reference Carroll and Booth125) , we decided to include all studies regardless of quality in our review as we wanted to capture a fuller account of the topic.

Policy implications

A preference for overweight body sizes by some African women need not be viewed as a barrier to addressing the rising challenge of overweight and obesity in Africa. A set of interventions, as outlined in the Behaviour Change Wheel(Reference Michie, Stralen and West126), could be proposed. For example, emphasis could be placed on education (i.e. increasing knowledge or understanding), persuasion (using communication to stimulate action) and enablement (i.e. increasing means and/or reducing barriers to increase capability or opportunity) interventions. These could include the following actions: (i) providing information to promote a healthy weight through diet and physical activity; (ii) educating the whole community about the gravity of the health risks of obesity and (iii) addressing the underlying attitudes that cause stigmatisation of people with HIV/AIDS and weight loss in general. In addition, conducting mass media campaigns could be used as a vehicle for changing attitudes and risks associated with obesity. Furthermore, younger participants have already expressed unwanted pressure to be slim from the media, as well as some ethnic groups in some African countries; therefore, care must be taken to ensure that educational campaigns do not shift body ideals too far in the other direction and precipitate eating disorders. Qualitative and mixed methods studies focusing on individuals’ perceptions of weight management and education programmes should also be conducted, so that their cultural acceptability and barriers to their use can be determined and used to design culturally acceptable programmes.

Conclusion

Obesity is an important public health issue with a high prevalence amongst African women. It is generally assumed that larger body sizes are preferred for African females. Overall, the evidence synthesised in this review found a preference for a normal and overweight (not obese) body sizes amongst African females. Factors influencing body size preferences were wide ranging. Whilst middle-aged and elderly women tended to value overweight, young women who are more exposed to norms in ‘Western’ media tended to value thinness and wanted to lose weight to improve health. Nevertheless, these perceived health risks were overshadowed by the community’s negative perceptions towards weight loss and thinness, which are associated with HIV and subsequently negative treatment by the community. A preference for overweight (not obese) body sizes among some African females means that traditional cultural norms may still be an obstacle for preventing overweight/obesity. The findings of this review highlight the need for interventions that account for the array of modifiable factors that maintain these preferences (e.g. education, SES, cultural norms, peer pressure and media) and for interventions to be tailored to different stages of the life course. Emphasis needs to be placed on education to prevent all forms of malnutrition such as promoting a healthy diet to help maintain a healthy body weight and raising awareness on the health consequences of obesity. The widespread preference for normal weight is positive in public health terms; however, the relative valorisation of underweight in adolescents and young women may lead to an increase in body dissatisfaction and eating disorders.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: None. Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: M.H. designed the research question with the help of R.P., O.O. and H.O. conducted the searches. M.H., R.P., E.C. and C.B.N. conducted the title, abstract and full text screening. H.O. and C.B.N. checked 10 % of all excluded records. R.P., O.O., E.C., M.H. and H.O. conducted data extraction and quality assessment. R.P. and E.C. led the synthesis with the help of A.I., O.O. and R.P. led the writing up of the manuscript with the help of E.C., M.H., A.I. and O.O. All authors took responsibility for the final editing, reviewing and approval of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021000768