Eating at least five portions of fruits and vegetables (F&V) a day is associated with a lower risk of CHD and some types of cancers(1). However, the majority of people in European countries do not comply with these dietary guidelines(2). Understanding the behavioural triggers that support the regular intake of fruit and vegetables (F&V) is, therefore, a public health issue of great relevance to national and international health priorities.

Recent research suggests that some purchase modalities (e.g. box schemes, farmers markets and cooperatives) may be more helpful in promoting healthier and more sustainable diets than others(Reference Bimbo, Bonanno and Nardone3,Reference Suarez-Balcazar, Martinez and Cox4) . Farm to table delivery programmes, known as ‘box schemes’, are growing across Europe and North America, innovating the distribution and marketing of fresh produce while mostly relying on Community-Supported Agriculture (CSA) projects, cooperatives or other farmer networks(Reference Ostrom, Kjeldsen and Kummer5,Reference Szabó, Lehota and Magda6) . These models typically ensure the regular provision of baskets of fruits and vegetables to consumers, based on a paid subscription fee to farmers that enables them to count on a stable stream of financial assets (sales or pre-sales) to their farming business(Reference Ostrom, Kjeldsen and Kummer5,Reference Wharton, Hughner and MacMillan7–Reference Thom and Conradie9) . Many such schemes rely on CSA initiatives that ensure not only a direct link between farmers and consumers but also the sharing of the risks related to the production process. Previous studies have mostly focused on the economic, social and environmental benefits of F&V boxes(Reference Ostrom, Kjeldsen and Kummer5). Only recently have the implications of these new purchasing modalities on diets and health been explored in the literature(Reference Allen, Rossi and Woods10).

Overall, subscription of these options has been linked with a higher consumption of F&V(Reference Brown and Miller8). The reported effects have relied on pre-post(Reference Allen, Rossi and Woods10–Reference Wilkins, Farrell and Rangarajan12), cross-sectional(Reference Bell, Khan and Lillefjell13,Reference Minaker, Raine and Fisher14) and qualitative research designs(Reference Wharton, Hughner and MacMillan7,Reference Lea, Phillips and Ward15) . From the consulted literature, the most robust evidence comes from North American experiences. For example, Cohen and collaborators(Reference Allen, Rossi and Woods10) designed a prospective cohort study targeting individuals affiliated with a seasonal CSA programme in New York city, before and after the beginning of the CSA season. The study allowed to compare the changes in food consumption behaviour between the two points in time among active and non-active participants. In comparison with non-active CSA members, active CSA members described a significant increase in servings of F&V and homemade meals before and after the CSA season. More recently, Wilkins et al. (Reference Wilkins, Farrell and Rangarajan12) assessed the differences in weekly vegetable consumption during a seasonal CSA programme cycle (before, after and mid season) among CSA members from a rural county in New York, finding that the entry in the programme is correlated with increases in vegetable consumption, vegetable exposure and increased vegetable preferences. Also in the United States, a study from the state of Kentucky, compared responses about food lifestyle behaviours and health outcomes pre and post enrolment in a CSA programme. Based on participant recall data, the results suggested positive impacts in dietary behaviour (including average daily F&V servings), health, especially among participants with lower perceived health (and reference). Cross-sectional studies with consumers enrolled with CSA programmes reached similar conclusions(Reference Cohen, Gearhart and Garland11,Reference Wilkins, Farrell and Rangarajan12,Reference Minaker, Raine and Fisher14) . Quantitative and qualitative designs identified perceived changes in dietary behaviours associated with the participation in CSA programmes, along with other benefits such as freshness, affordability or diversity of the food accessed(Reference Brown and Miller8,Reference Wilkins, Farrell and Rangarajan12,Reference Lea, Phillips and Ward15–Reference Quandt, Dupuis and Fish17) . Beyond the benefits related to diets and food, CSA participants also value benefits of the programme to farmers’ revenue as well as social and environmental impacts of food consumption (e.g.(Reference Wharton, Hughner and MacMillan7,Reference Wilkins, Farrell and Rangarajan12,Reference Lea, Phillips and Ward15,Reference Leone, Haynes-Maslow and Ammerman16) ). Additionally, although programme subscribers tend to belong to a specific population group, i.e. more educated, affluent and concerned both about their health and about sustainability(Reference Szabó, Lehota and Magda6), the literature does report on some successful interventions targeting lower socio-economic individuals and communities(Reference Leone, Haynes-Maslow and Ammerman16–Reference Hanson, Kolodinsky and Wang18), enabling physical and monetary access to box schemes from CSA programmes by families with lower socio-economic position.

While some studies discuss plausible mechanisms for explaining how the subscription influences dietary behaviour, such as vegetable exposure and/or purchasing and cooking habits, they do not test the relevance of these explanations. In fact, to our knowledge, very little is known regarding how box scheme programmes may influence behavioural triggers for more intake of fruits and vegetables. The current study is part of a wider research project – INHERIT (INter-sectoral Health and Environment Research for InnovaTion) – that evaluates practices that aim to promote healthier and more sustainable behaviours by modifying contexts to enable behavioural change(Reference Craveiro, Marques and Marreiros19). Within this scope, we selected the PROVE box subscription programme for its potential to shape proximal food environments. Box delivery enables consumers to gain access – weekly or biweekly, accordingly to the user choice – to boxes of fruits and vegetables from local farmers, enabling a higher consumption of F&V and less meat-centric diets than non-subscribers(Reference Bell, Khan and Lillefjell13). In the current study, we explore the key pathways that account for the higher likelihood of fruit and vegetable intake levels among PROVE box subscribers.

The PROVE subscription programme is a Portuguese ‘box scheme’ for local F&V. The programme delivers to different locations across the country and is accessible on-line through its website. PROVE subscriptions constitute a variation of community-supported agriculture programmes as it provides farmers with access to local networks for the direct selling of weekly subscription boxes of fresh produce. In turn, participating farmers ensure the provision of boxes of seasonal, locally produced fruits and vegetables all year round. The boxes come with a predetermined weight and contain three to five varieties of fruits and vegetables. The composition of the boxes depends on season and availability yet the share of vegetables and fruits is the same, with a third each of soup vegetables, salad vegetables and fruits of two or three varieties, as set out in the PROVE handbook for farmers. Also, farmers are prepared to customise the basket depending on consumers preferences – consumers can replace up to three F&V varieties. Consumers commit to paying for the boxes, which they can either pick up from a pre-determined location or have home delivered and are in direct contact with farmers. PROVE is a decentralised project and each local group is self-managed and can define different functioning rules. Overall, there is no minimum commitment for consumers and typically a phone call is sufficient to upgrade or downgrade the order with no penalisation. Still, being a PROVE subscriber entails a regular purchase of in season F&V.

Following the principles of retrospective process evaluations, the current study tests a set of theory-based, hypothesised mechanisms in order to better understand the components that make these programmes a promising way to enhance dietary practices(Reference Craig, Dieppe and Macintyre20). Although our design cannot establish causality between participation in the programme and F&V intake, it can help to disentangle relevant explanations associated with higher consumption among PROVE users. The hypothesised mechanisms are derived from the COM-B model(Reference Michie, Van Stralen and West21,Reference Van der Vliet, Staatsen and Kruize22) . According to this model, any given behaviour occurs when individuals have the required physical and psychological abilities to perform that action (Capability), a supportive physical and social context/environment (opportunity, e.g. regular exposure to F&V) and reflective (such as intentions, e.g. intention to follow a recommended diet) or automatic processes (e.g. habits, e.g. routinely ending a meal with a fruit portion) that energise/activate it (Motivation)(Reference Michie, Van Stralen and West21). This framework served to identify the possible mechanisms underpinning a greater probability of consumption of at least five portions of F&V/d among subscribers of F&V boxes in comparison with non-subscribers.

We intend to clarify the process around how a F&V box subscription may contribute to the probability of eating the recommended amount of F&Vs, by identifying the potentially relevant mediation effects between the subscription (PROVE) and the chances of eating at least five portions of F&V/d (five a day). The analysis was structured into three main sequential steps. First (1) we undertook preliminary studies to select the most relevant indicators of Capability, Motivation and Opportunity as related to F&V intake and available in the INHERIT Five-Country Survey(Reference Zvěřinová, Ⓢcasný and Máca23) (see online Supplemental materials Table A1); Then (2) a structural equation model was developed to estimated regression coefficients needed to and (3) estimate and assess the relevance of each mediation effect.

Methods

Participants

The study relies on the data of two non-randomised surveys collected online (the PROVE and INHERIT surveys). The modules common to these two questionnaires apply socio-demographic indicators and key determinants of fruit and vegetable intake levels and healthy eating identified in the literature(Reference Godinho, Carvalho and Lima24–Reference Story, Kaphingst and Robinson-O’Brien32). PROVE subscribers are compared with non-subscriber participants in the INHERIT survey of attitudes, preferences and behaviours related to consuming, moving and living. The formulation of the respective items took into account previous studies and was then validated in a pre-study phase(Reference Zvěřinová, Ⓢcasný and Máca23) – details in Supplemental Materials Table A1.

The PROVE survey was a self-selecting survey targeted to subscribers based on an online campaign via both the PROVE website, where consumers can check for programme updates and baskets composition, and across the social network channels belonging to the PROVE initiative. A chance to win a 1-month subscription payment was put forward as an incentive for participating in the study (selected randomly). Data were collected between November 2018 and January 2019 (n 295). PROVE is an ongoing project that entails a flow of users entering and leaving the programme. At the beginning of 2018, there were an estimated 4875 active users who were eligible to receive the survey.

The INHERIT Five-Country Survey constitutes one component of an international study on the attitudes, preferences and behaviours related to consumption, mobility and housing(Reference Zvěřinová, Ⓢcasný and Máca23). Paid online panels compose the INHERIT Survey sample, targeting representative samples of the adult population of the five countries involved by quota sampling. Data were collected between July and November 2018.

We considered only the Portuguese INHERIT Five-Country Survey sample and selected a subsample from the data available to improve survey comparability. First, this led to the exclusion of a few respondents because they reported buying fruits and vegetables by regular box schemes (based on the question ‘where do you buy your fruits and vegetables’). We then selected a subsample according to a propensity score matching procedure (coarsened exact matching) that identified matched cases in both surveys based on key demographic features (gender, age group, education group and region)(Reference Randolph, Falbe and Manuel33). For this process, a subsample of PROVE sample is taken as the target sample, considering only full data cases in matched variables (n 143). Bias treatment effects were made to assess if samples selection process biased estimation of eating at least five portions of F&V a day with endogenous switching regressions. No evidence for sample selection bias was found – reported elsewhere(Reference Bell, Khan and Lillefjell13).

This procedure led to the selection of a subsample of 571 cases. After combining the databases, the ‘PROVE’ variable served to identify the members of each of the two samples (‘subscriber’ and non-subscriber). A flow chart on the sampling process is presented (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Notes. 1To ensure data quality, the study only considered individuals that completed the questionnaire and excluded responders both who took <40 % of the median time for responding and those who took over three times the median response time. 2Propensity score matching procedure is ‘a statistical technique in which a treatment case is matched with one or more control cases based on each case’s propensity score’ to reduce selection bias ((Reference Randolph, Falbe and Manuel33), p. 1). The procedure was generated by R software and the Matchit package, using testing alternative techniques. The final selection was based on the Coarsened Exact Matching technique, since it ensured better results in terms of reducing the propensity scores between samples(Reference Bell, Khan and Lillefjell13). 3PROVE reference sample is a subsample composed by the cases with full data on the matching variables – gender, age group, education group and region (n 143)

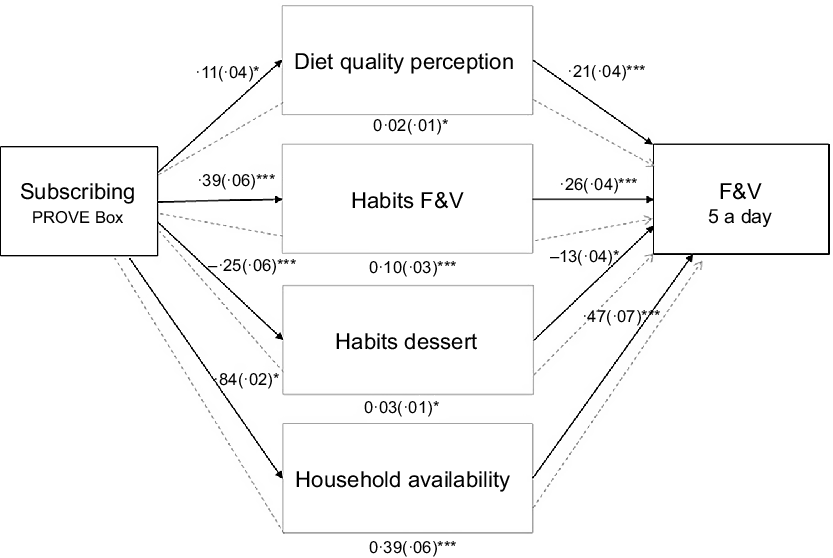

Fig. 2 Notes. Direct effects in black (full line arrows). Mediated effects in grey (dotted line arrows). Direct effect – paths (a), left side of the figure paths (b), right side of the figure – regression coefficients made comparable according to MacKinnon and Dwyer(Reference MacKinnon and Dwyer40). Control variables omitted in the figure. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001

Measures

Fruits and vegetables intake

A standardised fifteen items for the Self-Reported FFQ served for the collection of dietary information(Reference Zvěřinová, Ⓢcasný and Máca23,Reference Cleghorn, Harrison and Ransley34) . The frequency of consumption for each food group was asked about on separate screens complemented by visual depictions of a typical portion. Respondents were asked to indicate how often they consume fruits and vegetables separately (nine-point Likert scale). The daily portions of fruits and vegetables were estimated on the basis of the conversion table adopted by the authors(Reference Cleghorn, Harrison and Ransley34). The final variable resulted from the sum of daily portions of fruits and vegetables recoded as a dichotomous variable (five a day: less than five portions a day; five or more portions a day).

COM-B mediation variables

The selection of potential explanatory variables was based on data availability, their theoretical relevance and empirical validation criteria. The relevant variables established in the literature on the determinants of diet and diet change(Reference Godinho, Carvalho and Lima24,Reference Gardner25,Reference Evans and Stanovich35,Reference Wood and Rünger36) were identified in the survey – details in the Supplementary materials (see online Supplemental materials Table A1). The variables individually correlated with F&V irrespective of selected control variables (see online Supplemental materials Tables A2–A6) were considered as potential mediations.

In line with the literature, indicators for knowledge and self-regulatory skills were considered for assessing capability(Reference Godinho, Carvalho and Lima24). For motivation, indicators designed to assess behavior intention (to follow a recommended diet – including the intake of 5 F&V portions/d), values (health, sustainability and social justice) and habits were considered. For opportunity, indicators describing social and physical features of proximal context(Reference Bowen, Barrington and Beresford26,Reference Giskes, Avendaňo and Brug29,Reference Story, Kaphingst and Robinson-O’Brien32) were considered, including indicators concerning social norm for healthy eating, F&V household availability or perceived impact of higher affordability and accessibility (distance from store) to fruits and vegetables in stores, restaurants and public places on diet change.

From the initial set, the following four variables were selected as potential mediators: diet quality perception, strength of habit of consuming fruit after meals, strength of habit of consuming dessert after meals and F&V home availability index.

The diet quality perception variable addresses the capability domain of the COM-B model and assesses individual perceptions of how healthy their diet is on a scale of 1–7 (from 1, very unhealthy, to 7, totally healthy, in response to the question: how healthy do you think your diet is?), here taken as a proxy for knowledge on healthy eating.

Habits, in turn, concern the motivation domain and are defined as ‘a process by which a stimulus automatically generates an impulse towards action’(Reference Gardner25). In order to understand motivation for behaviour change, it is important to consider healthy and unhealthy habits interactions. Habits refer to contextualised-learned associations in which given situational cues would suffice to (automatically) start the behaviour without any deliberate decision to do so(Reference Gardner25), for example, serving a salad portion with the meal when the bowl is on the table. Our study measured the strength of two habits based on an adapted short version of the Self-Reported Habit Index(Reference Verplanken and Orbell37), considering the habitual intake (i) of fruits and/or vegetables (F&V habit assessed conjointly) and (ii) of desserts with main meals. Each habit strength score was computed by calculating the average score of six items, assessed on an agreement scale for three sentences concerning the lunch and dinner situation (‘Eating fruits or vegetables/dessert at lunch/dinner time on weekdays is something that…. I do without thinking;…is natural for me to do;…I do automatically’). Both measures demonstrated good internal consistency scores (fruit after meals Cronbach’s α = 0·913; dessert after meals, Cronbach’s α = 0·919).

Finally, the physical availability of fresh fruits and vegetables was measured by the household availability scale originally adapted from the Home Food Assessment tool(Reference Napper, Harris and Klein38). The score was computed by averaging three items that assessed the frequency of fresh fruit or vegetables available in the household, ready for consumption and visible at home on a scale from 1 to 7 (Cronbach’s α = 0·971).

Control variables

A set of socio-demographic variables were considered as control variables, specifically gender (female), age group (18–34 years old, 35–50 years old, 50+ years old), perceived economic difficulties (no difficulties, some economic difficulties) and education group (primary/lower secondary, upper secondary and tertiary). Education group is defined following the International Standard Classification of Education designations. The first category encompasses people with primary and lower secondary education (in Portugal, lower secondary education corresponds to full ‘basic’ education, ending after 9 years of schooling); the second category encompasses people with upper secondary, ending after 12 years of schooling in Portugal and tertiary education refers to college degree education.

Analysis

The analytical process was structured into three main steps. First, we undertook preliminary studies to select the most relevant indicators of Capability, Motivation and Opportunity as related to F&V intake and available in the INHERIT Five-Country Survey. These included descriptive, correlational and regression studies (see online Supplemental materials Table A1). The variables individually correlated with F&V irrespective of our selected control variables were selected as potential mediators (see online Supplemental materials Tables A2–A6).

The second step concerned the estimation of the direct and mediated effects of a PROVE subscription in eating at least five portions of F&V/d. This included calculating the structural equation model that incorporated the variables selected as mediators – the model accordingly includes paths concerning the effects of a PROVE subscription on the potential mediators and their respective effects on F&V intake levels. The initial model was adjusted by deleting non-significant paths and assessing the modification indices. This estimated the regression coefficients and fitness statistics according to the Lavaan package in R(Reference Rosseel, Jorgensen and Oberski39), based on robust estimations.

All the paths included the same set of control variables. The initial path included five equations (four predicting each potential mediator and one for F&V intake) and six correlation associations (pairwise correlations among all the potential mediators). In order to better adjust the model to the data, we then deleted the non-statistically relevant paths (P > 0·05). The final version of the structural equation model incorporates 842 cases due to missing dealing procedures (listwise) and estimates five regression equations and five correlation relations.

The model goodness of fit was evaluated by the normed χ 2 statistic (χ 2/df), the comparative fit index, the Tucker–Lewis index, the standardised root mean-square residual, and the root-mean-square error of approximation. As criteria, we considered a good data fit as duly reflected in the following scores: χ 2/df < 3, comparative fit index > 0·90, Tucker–Lewis index > 0·90, standardised root mean-square residual < 0·08, root-mean-square error of approximation IC90 % < 0·08, P < 0·05.

The third step involved estimating and statistically testing each potential mediation effect. The mediation effect was estimated by the product of the coefficients approach (the effect the coefficient produces on the independent mediator variable and the coefficient effect of the mediator on the dependent variable), after rendering the coefficients comparable(Reference MacKinnon and Dwyer40). Finally, a Sobel test was computed in order to assess the statistical relevance of each mediation effect.

Results

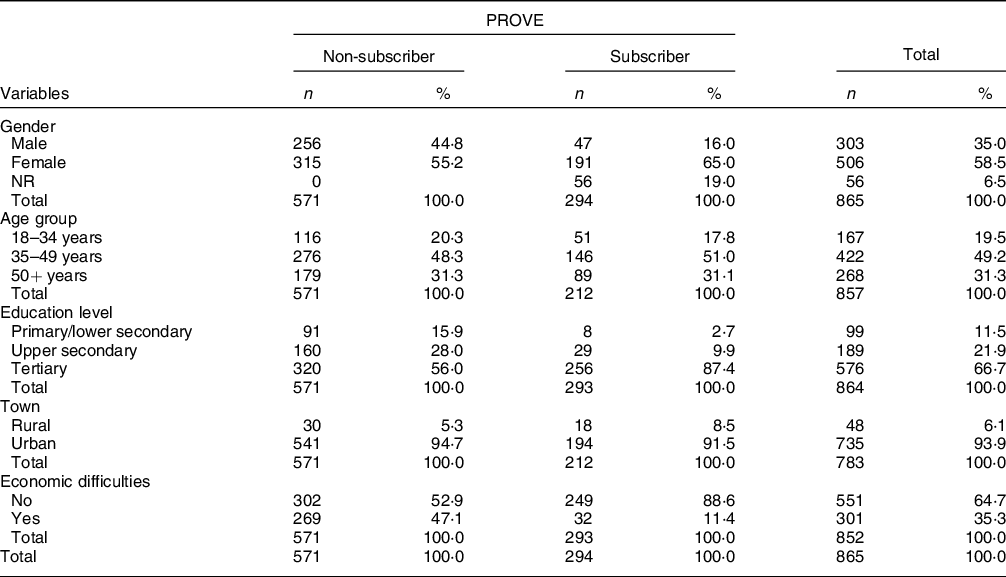

The study included a total of 865 participants (571 non-subscribers and 294 subscribers), mostly female (68·5 %), aged between 35 and 49 (49·2 %), with tertiary education qualifications (66·7 %), living in urban settings (93·9 %) without any perceived economic difficulties (64·7 %) (Table 1). Overall, 39 % of the sample consumed at least five F&V a day: 60 % among subscribers and 29 % among non-subscribers. PROVE baskets serve households of singles and couples (27 %), three people (30 %) and four or more people (33 %). A wide variety of subscription times in the programme was observed among responders (from only a few months up to 12 years), while the average subscription time was 1·5 years. Subscription time in the programme (less than 1 year, 1 year, 2 years and more than 2 years) and frequency of basket (weekly, biweekly, monthly and less than monthly) did not influence chances of having at least five portions a day of F&V after controlling for socio-economic variables (see online Supplemental materials Table A7).

Table 1 Sample description

n, frequency; %, percentage.

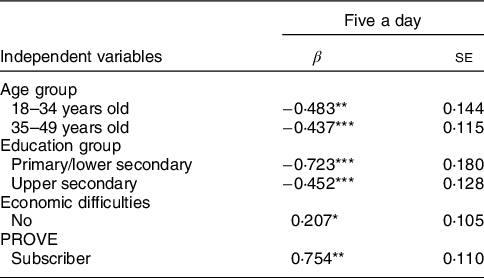

To confirm whether the differences between subscribers and nonsubscribers remain relevant after controlling for socio-demographic variables (i.e. gender, age, education and perceived economic difficulties), we estimated a regression model for the F&V intake variable (probit models). All the variables showed a relevant statistical effect on the probability of eating at least five portions of F&V a day (P < 0·05) (Table 2).

Table 2 Regression coefficients: simple equation

β, unstandardised coefficients.

* P < 0·05.

** P < 0·01.

*** P < 0·001.

The coefficients showed that the likelihood of eating at least five portions of F&V a day is lower among younger age groups (in comparison with people aged 50 or over), among lesser educated persons (in comparison with people with tertiary education) and higher among people without any perceived economic difficulties and among PROVE subscribers (Table 3).

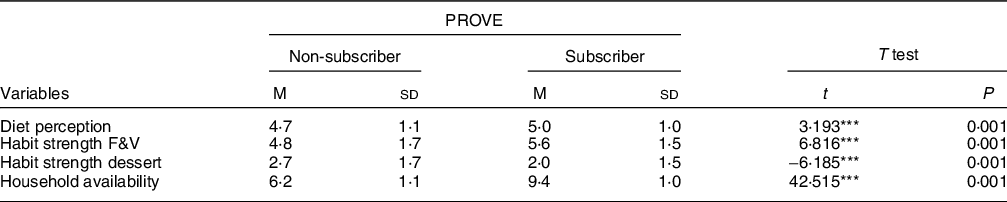

Table 3 Descriptives of potential mediators

M, mean; t, T-test statistics; P, significance.

*** P < 0·001.

All the variables selected as potential mediators differed significantly between the respective samples (P < 0·05) (Table 3). Subscribers had higher scores for perceived diet healthiness, habit strength regarding the eating of F&Vs at main meals, higher scores of household F&V availability and weaker habits of eating desserts after main meals.

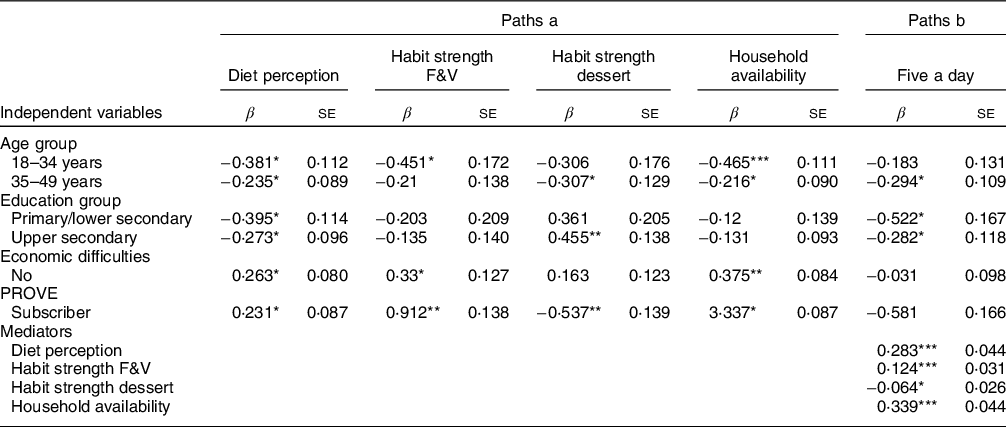

After these preliminary analyses, the structured equation model was estimated. Table 4 presents the final regression coefficients estimated in the path analysis to assess the mediation effects. The model reported a good fit to the data (χ 2/df = 2·60, comparative fit index = 0·997, Tucker–Lewis index = 0·974, SMRM = 0·011, root-mean-square error of approximationIC 90 % = 0·01, 0·196, P = 0·508).

Table 4 Regression coefficients from path model (n 842)

β, unstandardised coefficients. se, standard error.

* P < 0·05.

** P < 0·01.

*** P < 0·001.

As Table 4 sets out, in terms of the first set of equations (path a), the PROVE subscription correlates with the scores for diet quality perception, diet habit strength and household availability and is relevant independent of the socio-economic variables (control variables): subscribing to PROVE interlinks with healthier perceived personal diets, healthier eating habits (stronger habits of eating F&Vs and weaker habits of eating desserts at main meals) and higher household F&V availability scores (the R output is available for consultation in appendix, see online supplemental material Table A8).

In the F&V intake (path b) calculation results, it is interesting to observe, how in the equation considering the potential mediators, the subscription effect (PROVE) on the five a day variable loses significance (β = 0·581, P = 0·166), suggesting a total mediation effect, hence, suggesting the variables introduced explain the differentials between the samples (the PROVE variable) as regards the likelihood of consuming the recommended amount of F&Vs (Table 4).

The result of estimating each mediation effect derives from the product between the respective coefficients in path a and path b, after these were rendered comparable. Figure 2 depicts these converted coefficients with the significance of the mediation effect coefficients calculated by the Sobel test.

All the mediation effects emerged as both statistically relevant (Sobel test, P < 0·05). Since mediation effect coefficients are above zero (positive mediation effects), results suggest that the association between the F&V box subscription and a higher intake of F&V is partially explained by the shaping of diet quality perceptions, habits at main meals and on household availability that in turn raises the probability of eating at least five F&V portion/d. The operation standardises the regression coefficients to allow for comparisons between the effects on F&V intake. Among the mediators identified, household availability reports the highest estimate followed by the strength of the habit of eating F&Vs at main meals. These results indicate that the association between the PROVE subscription and dietary intake mainly arises from the higher availability of F&V in the household and the strength of habit in terms of F&V consumption at main meals.

Conclusion

Eating at least five portions of F&V/d is an important benchmark for promoting public health nutrition. F&V box subscription programmes have already been shown to be associated with higher levels of fruit and vegetable intakes(Reference Brown and Miller8), but evidence is still lacking in regards potential explanatory mechanisms. In the current study, we tested the potential explanatory factors behind the relatively higher fruit and vegetable intakes among F&V box scheme subscribers. Based on the COM-B model proposed by Michie and collaborators(Reference Michie, Van Stralen and West21), we were able to identify the main variables that significantly influence this process.

In our study, after controlling the effect of socio-economic factors, the subscriber advantages in F&V consumption stem from differences in diet knowledge, the strength of healthy habits (fruits and not dessert after main meals) and F&V household availability. Our results demonstrate higher daily F&V consumption among fruit and vegetable box subscribers is mediated by higher perception of diet quality (capability factor), higher habit strength in relation to eating F&Vs and not eating desserts (motivation factor) and the higher household availability of F&Vs (opportunity factor).

F&V availability in the household has been consistently signalled as a key contextual predictor of intake(Reference Jago, Baranowski and Baranowski41,Reference Trofholz, Tate and Draxten42) . In this sense, F&V basket schemes overcome initial difficulties arising from the lack of availability of fresh food in local grocery stores(Reference Bodor, Rose and Farley43) and place F&V right onto the plates of consumers. In keeping with how habit formation implies consistent exposure to situational cues, it is also plausible that the increased household F&V availability ends up supporting these processes and helps to overcome frequently cited barriers for F&V intake, such as forgetting to eat it(Reference Godinho, Alvarez and Lima44). This increase in available fresh food, coupled with an increase in F&V consumption habits and more positive perceptions may constitute an important trigger for change. Diet knowledge also helps support higher F&V consumption among subscribers. The PROVE box scheme and other F&V outlets bring consumers close to farmers, such as farmers’ markets, have been linked to consumer awareness of issues such as seasonality and F&V diversity(Reference Bell, Khan and Lillefjell13). Building knowledge and understanding about the importance of purchasing and preparing F&V may be an effective intervention for behaviour change(Reference Rekhy and McConchie45–Reference Ungar, Sieverding and Stadnitski47).

Overall, the study encountered relevance in three factors in the COM-B model dimensions that convey how higher F&V consumption receives support from both conscious (e.g. diet perceptions) and automatic (e.g. habit strength) individual factors, but also more structural environmental factors (e.g. F&V availability). This result concurs with dual models of information processing(Reference Strack and Deutsch48).

PROVE subscribers tend to be urban female, higher educated, with no economic difficulties – the upper socio-economic profile has been identified in other consumer studies of these subscribing schemes(Reference Szabó, Lehota and Magda6). Our study seeks to control its effects on the mediation studies, yet the identification of the socio-economic profile may signal a strategy not available or underused among less low resource people and households.

These results contain important practical policy implications and help to strengthen the arguments in favour of F&V basket schemes. By providing the opportunity to increase the availability of F&V in households, this type of alternative commercialisation scheme may indeed constitute a powerful policy tool for promoting healthier dietary patterns. Considering the importance of diet profiles rooted in socio-economic disadvantages, one way to upgrade is effect may be broad the social profile of consumers. Promotion campaigns should target those with less privileged socio-economic backgrounds by ensuring free or affordable options(Reference Leone, Haynes-Maslow and Ammerman16–Reference Hanson, Kolodinsky and Wang18). To enable less privileged socio-economic groups to use such schemes requires steps to make F&V box subscription affordable and desirable. Capabilities of diverse groups in the form of familiarity with produce varieties and cooking methods also need to be addressed(Reference Hampl and Sass49–Reference Moya and Hampl51).

To foster chances for behaviour change and increase of F&V intake, the programmes may be complemented with initiatives that help people integrate different F&V in meals and snacks (capabilities) – addressing reported unfamiliarity and low exposure to F&V variety seasonality in some low socio-economic groups(Reference Hampl and Sass49–Reference Moya and Hampl51) – and suggesting tips to include F&V in relevant contexts to make household availability evident (opportunity) and allow healthy habits development (motivation).

The current study adds to our understanding of the explanatory factors behind the increased consumption of F&V among F&V box scheme subscribers. Nevertheless, the identification of relevant facts was constrained by data availability. The surveys were developed built upon a broad literature review and on indicators tested and validated by previous research. This led to exclusion of some theoretical relevant factors due to operationalisation difficulties in a questionnaire format – such as the emotional factors (part of the motivation component(Reference Michie, Van Stralen and West21)).

Also, taking the correlational nature of the data into consideration, it is not possible to disentangle the causal relationships studied; it may be the case that individuals with previous higher F&V intake levels are those who opt to sign up to these box schemes in the first place. Hence, this requires intervention studies with randomly selected samples in the future to draw firmer conclusions regarding the actual nature of these relationships.

Another limitation stems from the subscriber sample registering higher levels of education, fewer economic difficulties and with a greater proportion of women, which all constitute socio-demographic variables previously associated with higher levels of F&V intake(Reference Irala-Esteves, Groth and Johansson52–54). Nonetheless, these were duly controlled for in the estimated regression models in which the tested mediators were able to explain differences in F&V intake over and above these socio-demographic predictors. Also, we attempt to compare matched samples from the two surveys, selected with a propensity score matching procedure (Fig. 1). Even though missing data hindered a more complete match between the groups, sample heterogeneity effect was studied with endogenous switching regressions that found no evidence for sample selection bias – reported in Craveiro et al. (Reference Bell, Khan and Lillefjell13).

Based on the behavioural change model ‘COM-B’, it was possible to identify relevant pathways by which a F&V box scheme contributes to F&V intake. Differences in F&V intake levels between subscribers and non-subscribers of PROVE can be attributed to differences in home F&V availability, the strength of meal habits and perceptions of diet quality, in terms of healthiness. The benefits of such programmes should be extended by devising strategies to target low-income households and poor socio-economic backgrounds(Reference Leone, Haynes-Maslow and Ammerman16–Reference Hanson, Kolodinsky and Wang18), fostering knowledge regarding healthy diets(Reference Rekhy and McConchie45), and enabling people to shape proximal environments, in order to associate F&V consumption to relevant meal contexts through making F&V easily accessible, and thereby fostering the development of F&V consumption habits(Reference Vecchio and Cavallo55).

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Natalia Henriques and all the team from ADREPES for the support and collaboration with the evaluation process; Isabel Rodrigo (ISA-UL) and Luisa Lima (ISCTE-IUL) for their contributions to the evaluation model; Iva Zvěřinová, Milan Ⓢⓒasný and Vojtěch Máca (Charles University Environment Centre) for coordinating and providing access to data from the INHERIT Five-Country Survey; and Ana Marreiros and Eunice Lopo (ISCTE-IUL) by supporting PROVE survey data collection. Financial support: The evaluation was developed as part of EuroHealthNet coordinated INHERIT project (www.inherit.eu) funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 667364. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: Conceptualisation, D.C., S.M.; Literature review, F.P., D.C.; Formal analysis, D.C.; Methodology, S.M., R.B. and M.K.; Supervision, S.M., R.B. and M.K.; Writing – original draft, D.C.; Writing − review & editing, S.M., R.B., M.K., C.G., F.P. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (Lisbon, Portugal, 24/2017). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021003839