Engaging with food retailers to create environments that encourage consumers to choose nutritious options aligned with the 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA)(1) may be an important step to address obesity in the USA(Reference Haddad, Hawkes and Webb2–5). Currently, food store retailers use marketing-mix and choice-architecture (MMCA)(Reference Kraak, Englund and Misyak6) strategies to prompt consumer purchase of foods and beverages high in saturated fats, added sugar and sodium(1,Reference Cohen and Babey7–Reference Rivlin9) . As estimates indicate more than 71 % of US adults and 52 % of youth are high risk for adverse health conditions on the basis of BMI (kg/m2 ≥ 25)(10), food retailers have been under increasing scrutiny for their influence on the quality of consumers’ dietary choices(Reference Swinburn, Sacks and Hall4,5,Reference McKee and Stuckler11–Reference Tempels, Verweij and Blok13) .

Underserved US consumers may be most vulnerable to business practices that favour the consumption of energy-dense and nutrient-poor dietary products(Reference Thompson, Cummins and Brown14,Reference Fielding-Singh15) . For example, the US Department of Agriculture’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) participants may be disproportionately targeted for unhealthy product advertisements(Reference Powell, Wada and Kumanyika16,Reference Yancey, Cole and Brown17) and experience reduced access to foods and beverages aligned with the DGA(Reference Larson, Story and Nelson18,Reference Hilmers, Hilmers and Dave19) . These factors likely contribute to the lower dietary quality scores of SNAP consumers’ food and beverage purchases when compared with the dietary purchases of higher-income consumers(Reference Mancino, Guthrie and Ver Ploeg20,Reference Lacko, Popkin and Smith Taillie21) . The identification of shared goals between food retail businesses and public health nutrition priorities may help to initiate feasible marketplace change within SNAP-authorised stores that support improved SNAP dietary quality and retailers’ interests (e.g. profits)(Reference Davis and Serrano22,Reference Houghtaling, Serrano and Kraak23) .

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is a voluntary platform for corporations to commit to using their reach to help improve social and environmental issues(Reference Rockefeller24–Reference Bhattacharya, Hildebrand and Sen26) and could be a useful tool for assessing the alignment/misalignment of public health nutrition objectives with business models (e.g. commercial viability)(Reference Blake, Backholer and Lancsar27). For example, researchers have explored food retailers’ CSR commitments to improve food system sustainability(Reference Pinard, Byker and Serrano28) and consumer nutrition behaviours(Reference Pulker, Trapp and Scott29,Reference Jones, Comfort and Hillier30) . However, commitments to use MMCA strategies that favour DGA-aligned products could impact populations’ dietary quality(5,Reference Kraak, Englund and Misyak6,Reference Arno and Thomas31) and have not been assessed within the context of CSR or SNAP. Therefore, researchers explored the availability of SNAP-authorised food retailers’ public commitments to encourage consumer purchase of products aligned with the DGA using a MMCA framework(Reference Kraak, Englund and Misyak6).

Methods

A cross-sectional review of publicly available information was conducted from November 2016 to February 2017 among prevalent SNAP-authorised retailers. The availability of retailers within a geographic location may vary by format (e.g. grocery, convenience, dollar, drug) and parent corporation (e.g. national v regional chains)(32). SNAP-authorised retailers with the most store locations nationally and in two regionally different states were selected based on a targeted social marketing campaign. For example, the Partnership for a Healthier America (PHA) aims to favourably influence food retailers’ practices(33) and piloted a fruit and vegetable marketing campaign in one city in California and in Virginia(Reference Kraak, Englund and Zhou34). These states were chosen to identify prevalent SNAP-authorised retailers potentially influenced by PHA.

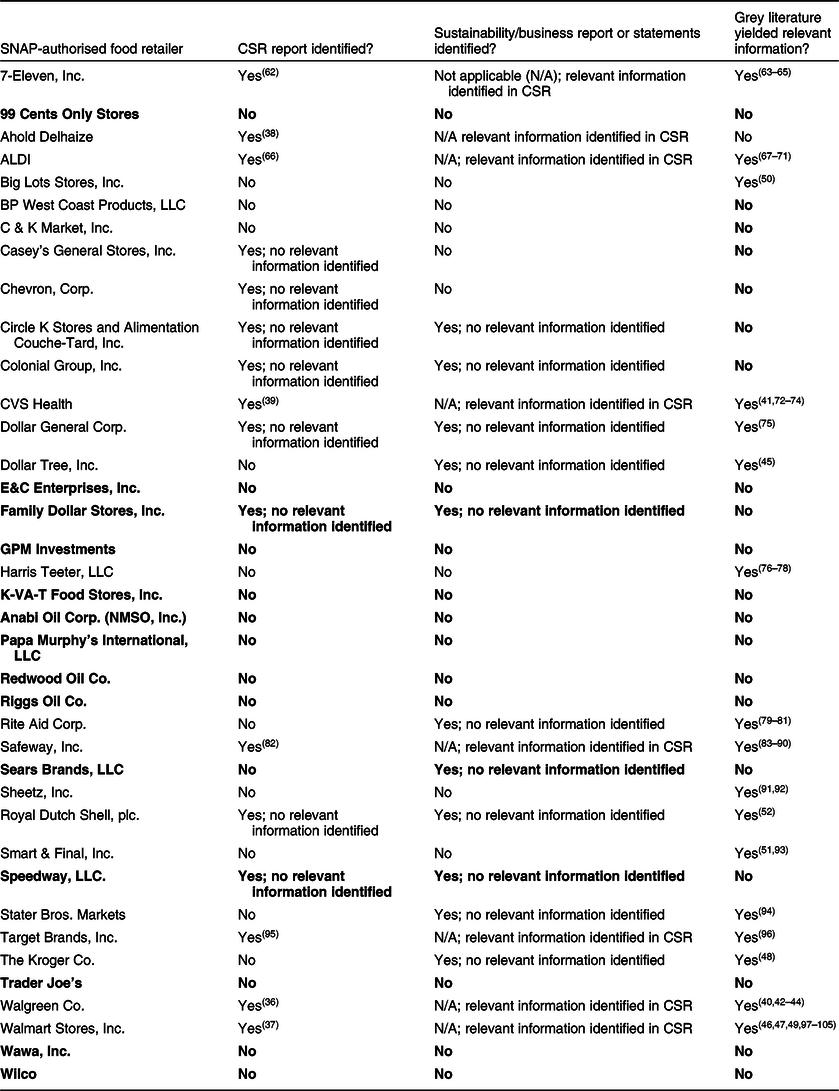

In 2016, the top fifteen retailer corporations/chains (by number of store locations) were systematically selected each at a national level, state level, and in urban and rural areas within each state (using Rural-Urban Continuum Code classifications)(35). This method was intended to capture stores more widely available in rural but not urban areas (or vice-versa) to broaden the scope of research results for relevance to hard-to-reach areas. Stores were identified using the SNAP Retailor Locator(32). SNAP-authorised retailer search results by location are available upon request; retailers identified for research inclusion using this method are listed in Table 1.

Table 1 Public corporate social responsibility (CSR) commitments of prevalent Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)-authorised food retailers to use marketing-mix and choice-architecture strategies to encourage healthy consumer purchases aligned with dietary guidance in the USA, n 38

Bolded text indicates no relevant information identified among all searches.

Publicly available commitments

Methods for identifying relevant information included: (i) SNAP-authorised retailers’ business reports and (ii) a grey literature search. To be noted as available, data needed to focus on the use of in-store strategies to encourage consumer purchasing behaviours aligned with the DGA. For example, the DGA recommends the consumption of foods and beverages low in saturated fats, added sugars and Na(1), such as multiple forms of fruits, vegetables, lean and plant-based proteins and low-fat dairy products. This excluded gluten-free or natural products, for example. Also, due to the research focus on SNAP, all nutrition commitments were required to be US based. Figure 1 shows a visual representation of the search process for the identification of relevant, public information described below.

Fig. 1 Process used to review and identify relevant corporate social responsibility (CSR) commitments of prevalent supplemental nutrition assistance program-authorised retailers in the USA to use marketing-mix and choice-architecture (MMCA) strategies to encourage healthy consumer purchases

Webpage searches

Retailers’ corporate webpages were identified between 3 November 2016 and 7 November 2016 using Google. A researcher browsed materials to identify CSR reports and/or webpages describing business practices. If no CSR report was identified, annual or business reports were scanned for information aligned with the research focus. Sustainability reports were also scanned in this instance; however, none were found to include relevant information. It was assumed CSR reports indicated a stronger commitment by SNAP-authorised retailers to enhance consumers’ dietary quality than press releases or statements.

Grey literature search

A Research Librarian helped form the search strategy and key terms. Three databases were used to capture national as well as regional information: LexisNexis Academic; Access World News; and Ethnic News Watch. Search terms included the SNAP-authorised retailers’ name (Table 1) (e.g. 7-Eleven) along with key words: healthy food(s), nutritious option(s), dietary choice(s), healthy choice(s), fruit*, vegetable*, whole grain(s), low fat dairy, healthy snack(s), healthy diet(s) and nutrition. PHA began engaging with food industry stakeholders in 2010 to address childhood obesity(33); therefore, all articles published during or after this time were of interest. The search was conducted between 19 January 2017 and 2 February 2017. Items (n 2712) were extracted to EndNote and reviewed for study relevance. Duplicate reports from multiple sources were removed, and fifty-two independent items were found to meet the study focus. Search results are available in Table 1, which displays the types of materials identified or not identified for research inclusion.

Marketing-mix and choice-architecture framework

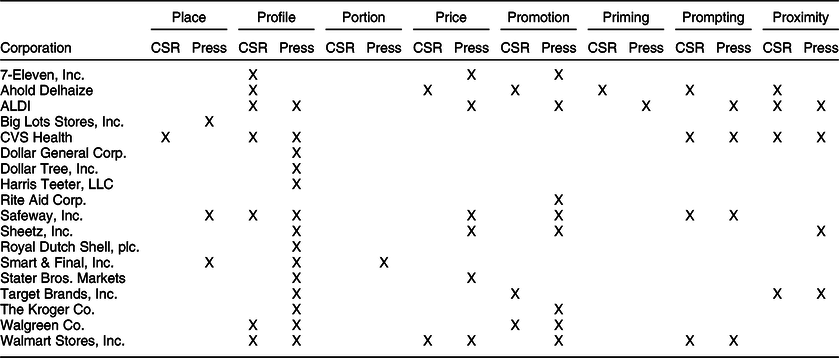

Researchers extracted SNAP-authorised retailers’ commitments to a MMCA framework. Eight MMCA categories identified as relevant to food stores(Reference Houghtaling, Serrano and Kraak23) were used to standardise and compare the availability of language in support of encouraging healthy consumer purchases: place, profile, portion, pricing, promotion, priming, prompting and proximity(Reference Kraak, Englund and Misyak6). For example, place strategies included changes to the structure or atmosphere of stores to encourage DGA-aligned food and beverage purchases. Profile strategies included commitments to improve the availability of DGA-aligned products. Portion strategies altered product sizes. Pricing strategies focused on improving the affordability of DGA-aligned choices. Promotion strategies included in-store marketing approaches to encourage healthy product purchases. Priming strategies included the use of subtle visual cues and prompting strategies the use of labelling. Last, proximity strategies included moving the physical location of DGA-aligned products to enhance their convenience to consumers(Reference Kraak, Englund and Misyak6).

Results

Of the SNAP-authorised retailers (n 38) reviewed, more than half (n 20; 52·6 %) provided no information in the public domain relevant to encouraging consumers’ dietary purchases to align with the DGA (presented using bolded text in Table 1). Few retailers (n 8; 21 %) had relevant CSR information, and grey literature sources (n 52 articles across seventeen retailers) were more commonly identified (Table 1). Most retailers described business strategy commitments focused on increasing the number of DGA-aligned products available (profile strategies) (Table 2). Commitments minimally reflected retailers’ use of other MMCA categories, with portion strategies the least regularly documented (n 1).

Table 2 Available* corporate social responsibility (CSR) or press information of prevalent Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)-authorised retailers in the USA to use marketing-mix and choice-architecture strategies to encourage healthy consumer purchases

* The number of SNAP-authorised retailers committing to use marketing-mix and choice-architecture strategies were place, n 4; profile, n 16; portion, n 1; price, n 7; promotion, n 10; priming, n 2; prompting, n 5; and proximity, n 5.

SNAP-authorised retailers’ commitments in majority seemed to indicate broad reach regarding strategy implementation within all store locations; however, at times commitments identified within press sources indicated smaller-scale health promotion strategies used only in a regional subset of store locations(36–52). For example, a Dollar Tree location discontinued the sale of sugar-sweetened beverages in response to the Berkeley soda tax and a select Shell store in Massachusetts partnered with practitioners to offer more healthful options(Reference Clough and Rodriguez51,52) .

Discussion

SNAP-authorised retailers have the potential to favourably influence the dietary behaviours of numerous US shoppers, including vulnerable SNAP consumers(5,Reference Mancino, Guthrie and Ver Ploeg20,32) . This research identified SNAP-authorised retailers with the most store locations in the USA and within two states influenced by a PHA campaign to examine commitments to alter the store environment to promote product purchases aligned with the DGA(Reference Kraak, Englund and Misyak6,Reference Houghtaling, Serrano and Kraak23) . However, few commitments were identified overall. Of available commitments, a limited number were committed to store changes beyond expanding consumers’ selection of healthy foods and beverages.

These results align with other work that has in majority identified food retailers’ commitments to environmentally sustainable practices rather than to obesity reduction strategies(Reference Pinard, Byker and Serrano28–Reference Jones, Comfort and Hillier30). Sustainability commitments reflect consumer demand for environmentally friendly practices(53) and the focus on profile or product stocking changes that were most commonly identified in this research likely reflects an increased consumer demand for healthy products(Reference Steingoltz, Picciola and Wilson54). However, while food system sustainability is a necessary component of global health, food retailers are not advised to commit to one goal without the other as both are inherently interconnected(Reference Swinburn, Kraak and Allender3). Partnerships may help retailers and public health practitioners achieve goals for this sector in support of reducing high rates of consumer obesity(10).

Results of this research may inform SNAP-authorised retailers who would be most open to healthy retail partnerships with local SNAP-Education organisations(Reference Blake, Backholer and Lancsar27,55) , due to their public commitments to consumer health and store availability of DGA-aligned products(Reference Houghtaling, Serrano and Kraak23,Reference Kraak, Harrigan and Lawrence56) . In contrast, the many SNAP-authorised retailers with no identified commitments may indicate opportunities for dynamic teams (e.g. nutrition scientists, health economists, corporate marketing professionals) to create mutually beneficial CSR messaging to favourably impact business outcomes and consumers’ dietary behaviours(Reference Bhattacharya, Hildebrand and Sen26). However, the recommended approach remains inconclusive, and more research is warranted to define best approaches.

Qualitative inquiry will be important to understand corporate retailers’ rationale for limited CSR that supports healthy consumer behaviours. While the lack of SNAP-authorised retailers’ commitments to use MMCA strategies to encourage DGA-aligned purchases likely indicates poor fit with business models that balance social issues and profits (revenue minus costs)(Reference Davis and Serrano22,Reference Blake, Backholer and Lancsar27,Reference Glanz, Resnicow and Seymour57) , evidence suggests improving the selection of DGA-aligned products in isolation may not be enough to improve dietary behaviours and product sales(Reference Cummins, Flint and Matthews58). Therefore, if retailers are committing to making healthy products available, it may be within their best business interest to use comprehensive MMCA strategies to nudge sales(Reference Arno and Thomas31). More research is needed to explore the impact of scaling up MMCA strategy implementation on outcomes of costs, revenue, and overall profit among corporate chain retailers.

SNAP-authorised retailers may also be committed to promoting consumer health in other ways, not captured by this research. A recently published Business Impact Assessment–Obesity (BIA-Obesity) tool scores retailers on store promotion variables as well as corporate relationships and strategies to improve consumer health more broadly(Reference Sacks, Vanderlee and Robinson59). Application of this tool among SNAP-authorised retailers with large reach in US communities is needed (forthcoming). Holistic knowledge of corporate strategies to improve consumers’ dietary quality and reduce the prevalence of obesity may help leverage meaningful public–private partnerships and/or policy intervention within this sector(5,Reference Kraak, Harrigan and Lawrence56,Reference Sacks, Vanderlee and Robinson59) . However, despite the utility of scoring SNAP-authorised retailers using BIA-Obesity(Reference Sacks, Vanderlee and Robinson59), the tool does not include comprehensive MMCA strategy indicators(Reference Kraak, Englund and Misyak6). Therefore, the approach used in this research could prove a useful complement to future, similar studies.

Finally, at the time of this investigation, three SNAP-authorised retailers identified for research inclusion were engaged with PHA to promote health among their consumer base(33). This engagement likely influenced their CSR communications. To maximise the impact, PHA should consider the use of the MMCA framework(Reference Kraak, Englund and Misyak6) as a guide for future food retailer engagements that aim to improve store variables and improve consumer health outcomes. However, currently, there is a lack of information about how and if CSR translates to the food store environment to influence behaviour. Lam et al. (2018) found that corporate retailers’ policies regarding healthy checkout lanes were linked with the purchase of healthy products(Reference Lam, Ejlerskov and White60). More investigations are warranted that link CSR messaging to favourable food store change, as food retailers’ accountability on this front is controversial(Reference Bhattacharya, Hildebrand and Sen26,Reference Brownell and Warner61) .

Limitations

This research was a novel approach to understand prevalent retailers’ commitments to improve the dietary quality of vulnerable US consumers. However, the captured commitments may underrepresent SNAP-authorised retailers’ strategies to improve consumer behaviours using MMCA strategies as low-sodium, saturated fat, or added sugar were not used for grey literature search terms. The selected databases may have been inadequate in identifying literature, as Google was not utilised and would have identified social media outlets where information may be posted. Despite these limitations, all SNAP-authorised retailers’ webpages and potentially relevant reports were identified and searched systematically for CSR language about encouraging healthy consumer purchases. It was assumed that these sources would have provided robust evidence of SNAP-authorised retailers’ health promotion strategies and were limited in number. Further, one author was responsible for extracting information meeting the research scope and there was potential for bias without multi-author agreement. The search for data occurred up to 3 years before publication and may not represent contemporary practices, and an ‘available’ commitment does not indicate strategy comprehensiveness at the store level.

Conclusion

Substantial improvements are needed to enhance the capacity and commitments of SNAP-authorised retailers to use diverse strategies to promote healthy purchases among SNAP recipients. Future research could explore feasible approaches to improve dietary behaviours through sector changes via public–private partnerships, policy changes or a combination of government regulatory and voluntary business actions.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: Virginia Pannabecker, Health, Life Science and Scholarly Communication Librarian at Virginia Tech, for helping to construct the search syntax and select search databases. Financial support: None to report. Conflict of interest: Authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. Authorship: B.H. is responsible for leading the research including research inception, study design, data analysis, manuscript writing and revisions. E.S. contributed to the research inception, study design, data interpretation and editing. V.I.K., S.M.H., G.C.D. and S.M. contributed to study design, data interpretation and editing. All authors edited and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This research did not utilise human subjects and was exempt from Virginia Tech’s Institutional Review Board review.