Green tea is derived from the plant Camellia sinensis and is the second most popular beverage worldwide, behind only drinking-water( Reference Hajra and Yang 1 ). Because green tea has not been fermented, most of its natural phytochemicals are preserved; of which tea polyphenols represent the highest proportion( Reference Lin, Tsai and Tsay 2 ). Tea polyphenols is a mixture of polyhydroxy phenolic compounds present in tea (especially green tea) whose main components are catechins (i.e. epigallocatechin-gallate, epigallocatechin and epicatechin-gallate), flavones, flavonols and anthocyanidins( Reference Zhang, Ni and Li 3 ). Several animal studies( Reference Wang, Wang and Wan 4 – Reference Zhong, Huan and Cao 6 ) and reviews( Reference Kim, Quon and Kim 7 – Reference Basu and Lucas 9 ) have found that tea polyphenols have a variety of biological effects, including antimutation, anticancer, antioxidation, bacteriostatic and bactericidal actions, and protective effects on the nervous and cardiovascular systems. These results further promoted the worldwide popularity of green tea.

The stomach is a major organ of the digestive tract and an essential place for food after entering the body. During the digestive process, food often stays in the stomach for a long time; thus, food has extensive direct or indirect contact with the stomach wall (especially the cells of the gastric mucosa layer). A variety of chemical constituents in food have various impacts on the stomach microenvironment or directly on the cells of the gastric mucosa layer( Reference Goldman and Schafer 10 ). The occurrence of gastric cancer is closely related to lifestyle, environmental and genetic factors, such as drinking, smoking, high-salt diet, diet lacking fresh vegetables and fruits, Helicobacter pylori infection, and family history of gastric cancer( Reference Compare, Rocco and Nardone 11 – Reference Zhou, Du and Chen 13 ).

Gastric cancer is one of the most common gastrointestinal malignancies( Reference Ferlay, Soerjomataram and Dikshit 14 ). The incidence rate of gastric cancer in 2012 ranked it as the fifth most common cancer worldwide, following lung cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer and prostate cancer( Reference Ferlay, Soerjomataram and Dikshit 14 ). More than 70 % of the diagnosed cases originated from developing countries, and half of the cases were from East Asia (especially China). Gastric cancer ranked third in terms of mortality( Reference Ferlay, Soerjomataram and Dikshit 14 , Reference Bray, Ren and Masuyer 15 ). Radical surgery is currently the most effective physical treatment. The prognosis of patients with gastric cancer is poor, making gastric cancer is a serious public health problem( Reference Kamangar, Dores and Anderson 16 , Reference Ferlay, Shin and Bray 17 ). Many epidemiological studies on the correlation between green tea and the risk of gastric cancer have been reported, but their results are inconsistent( Reference Wang, Duan and Yang 18 – Reference Yu, Zhang and Yu 33 ). A large number of case–control studies( Reference Wang, Duan and Yang 18 , Reference Liu, Zhao and Zhang 21 , Reference Inoue, Tajima and Hirose 28 , Reference Yu, Hsieh and Wang 30 ) reported that drinking green tea reduced the risk of gastric cancer, but a large number of case–control( Reference Mao, Jia and Zhou 20 , Reference Setiawan, Zhang and Yu 23 , Reference Huang, Tajima and Hamajima 26 , Reference Ji, Chow and Yang 29 ) and cohort studies( Reference Nechuta, Shu and Li 19 , Reference Hoshiyama, Kawaguchi and Miura 22 , Reference Tsubono, Nishino and Komatsu 24 , Reference Nagano, Kono and Preston 25 , Reference Galanis, Kolonel and Lee 27 ) also reported that drinking green tea had no effect on the incidence of gastric cancer. Data regarding the risk of gastric cancer for different doses of green tea exposure are also inconsistent. Green tea consumption may have a dose–response relationship with the occurrence of gastric cancer. Therefore, we conducted a dose–response meta-analysis of observational studies to quantify the correlation between green tea intake and the risk of gastric cancer.

Methods

Literature search strategy

Chinese and international published studies on the correlation between the consumption of green tea and the occurrence of gastric cancer were collected by searching PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, CBM, CNKI and VIP databases. The retrieval time was from the establishment of the database to December 2015. Information from related conferences was manually retrieved from the library of the Third Military Medical University. The keywords for the search were ‘green tea’, ‘camellia sinensis’, ‘gastric’, ‘stomach’, ‘cancer’, ‘neoplasm’ and ‘tumor’. The detailed search strategy for PubMed is provided in the online supplementary material, Table S1.

Study selection

Studies which met the following eligibility criteria were included: (i) cohort study, case–control study or nested case–control study; (ii) gender and age of the study participants were not restricted, and patients with primary gastric cancer were diagnosed based on the relevant international diagnostic criteria; (iii) the exposure of interest was intake of green tea (needed to be brewed and not blended drinks) and other lifestyle habits (i.e. smoking and drinking), excluding tea beverages and pre-made tea products; (iv) baseline data availability for the control group was the same as for the study group; and (v) for dose–response analysis, the number of cases, participants or person-years for each category of green tea intake (or data available to calculate them), and OR, relative risk (RR), hazard ratio (HR) and 95 % CI were also provided. If data were duplicated in more than one study, the study with the largest number of cases was included.

Data extraction and quality assignment

In accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria, two investigators (Y.H.H. and H.R.C.) independently screened the studies, extracted the data and evaluated the quality. In the case of disagreement, the decision for inclusion of a study was made through discussion or by a third investigator (L.Z.).

The data extracted from the contents included: (i) general information (first author, year of publication, age, sample source and observation year); and (ii) outcome indicators (the number of cases, participants or person-years for each category of green tea intake, multivariate-adjusted effect size and 95 % CI after adjustment, and the corresponding adjustment factors).

The quality of the included studies was evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS)( Reference Stang 34 ). The full score on the NOS is 9, and the included studies were evaluated based on the three aspects of selection, comparability and outcome( Reference Wells, Shea and O’Connell 35 ). Studies with NOS scores of 7, 8 or 9 were regarded as high quality; other scores were considered to indicate low quality.

Statistical analysis

Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I 2 statistic and χ 2 test. Heterogeneity was confirmed with a significance level of P≤0·10. For the I 2 metric, we defined low, moderate and high I 2 values to be 25, 50 and 75 %, respectively.

If statistical heterogeneity was evident across the studies (I 2>50 %), a random-effects model was selected to estimate the overall OR (for case–control studies) or RR (for cohort studies) and 95 % CI for the highest v. the lowest dose of green tea intake( Reference Higgins and Thompson 36 ). Otherwise, a fixed-effects model was applied. If the studies reported the results separately for men and women, we combined the gender-specific estimates using a fixed-effects model to generate an estimate for both genders combined. The statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software package Stata version 11.0.

We used a random-effects model to calculate the summary effect size and the 95 % CI for the non-linear dose–response analysis. We evaluated a potential linear curve for dose, years and temperature of green tea intake and the risk of gastric cancer using restricted cubic splines with three knots at the 10th, 50th and 90th percentiles of the distribution( Reference Harrell, Lee and Pollock 37 ). The method requires that the distributions of cases and person-years or non-cases and the effect size with the variance estimates for at least three quantitative exposure categories are known. We estimated the distribution of cases or person-years in studies that did not report these variables but reported the total number of cases and person-years (supplemental Material 1, available at Annals of Oncology online)( Reference Aune, Greenwood and Chan 38 ). If the study reported the mean or median of green tea intake, these values were directly used in our analysis; if the values were not reported, the midpoint of each dose range was used as the mean intake. If the lowest dose group had an open interval, 0 was assigned as the lower limit of the dose range. If the highest dose group had an open interval, the same interval length as the next group was assigned. The dose of green tea intake for all studies was unified into the same unit (cups/d). When the dose of the green tea intake was reported in grams, millilitres or batches, it was converted into cups (1 g=100 ml=1 batch=1 cup)( Reference Tsubono, Nishino and Komatsu 24 ). When the unit of time was reported as annually, monthly or weekly, it was converted to daily (multiplied by 1/365, 1/30 and 1/7, respectively). The original studies did not provide the specific drinking temperature of the green tea; instead, five grades of green tea consumption (undrinkable, cool (<35°C), warm (35–46·9°C), hot (47–54·9°C) and very hot (55–67°C))( Reference Li, Shimada and Sato 39 ) were assigned and given values of 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4, respectively, for the dose–response meta-analysis. The meta-analysis of the dose–response relationship was conducted using the software R 3.1.2 (package: mvmeta, dosresmeta, Hmisc, survival, SparseM and rms).

Potential publication bias was assessed by the application of funnel plots, Egger’s linear regression test and Begg’s rank correlation test at the P<0·10 level of significance. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to investigate the influence of a single study on the risk estimate by omitting each study individually. These analyses were performed using Stata version 11.0.

Results

Literature search

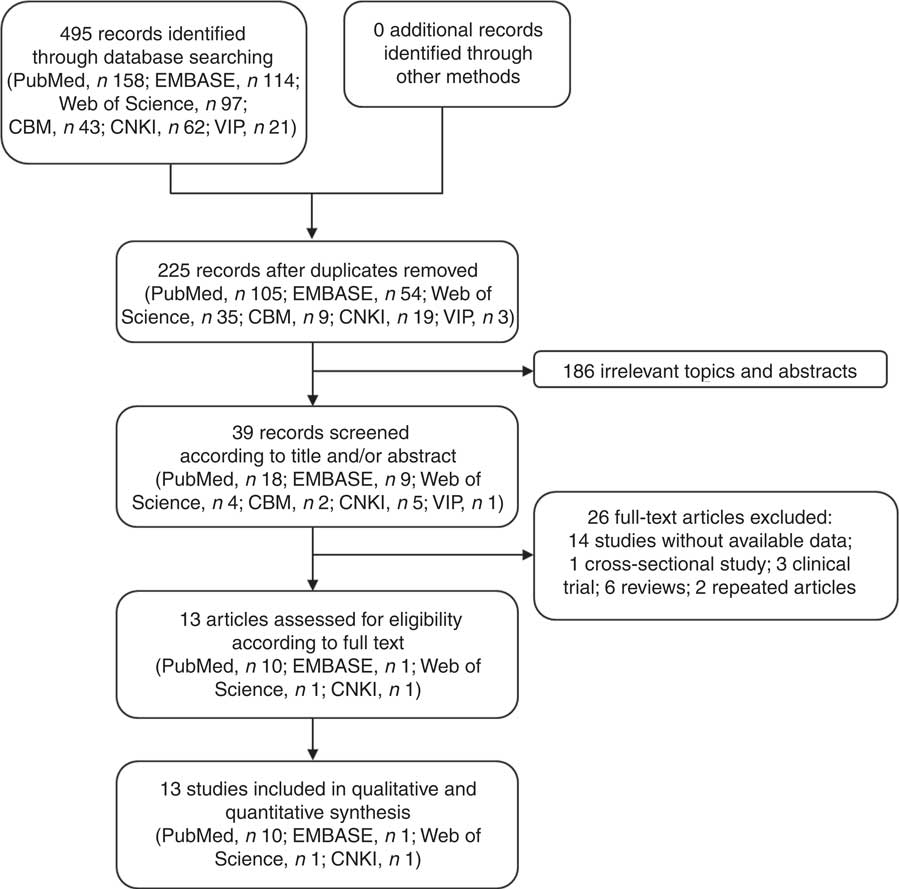

We obtained 495 studies during our initial electronic search. After screening the titles and/or abstracts, 186 studies were excluded because they had no relevance to our analysis. After screening the full text, we excluded fourteen studies with no data available, one cross-sectional study, three clinical trials, six reviews and two repeated articles. Finally, thirteen studies satisfying the eligibility criteria met the inclusion criteria for our meta-analysis (Fig. 1)( Reference Wang, Duan and Yang 18 – Reference Yu, Hsieh and Wang 30 ).

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of the literature search and selection of studies for the current meta-analysis on green tea intake and risk of gastric cancer

Study characteristics

The present review included a total of thirteen observational studies, with five cohort studies( Reference Nechuta, Shu and Li 19 , Reference Hoshiyama, Kawaguchi and Miura 22 , Reference Tsubono, Nishino and Komatsu 24 , Reference Nagano, Kono and Preston 25 , Reference Galanis, Kolonel and Lee 27 ) and eight case–control studies( Reference Wang, Duan and Yang 18 , Reference Mao, Jia and Zhou 20 , Reference Liu, Zhao and Zhang 21 , Reference Setiawan, Zhang and Yu 23 , Reference Huang, Tajima and Hamajima 26 , Reference Inoue, Tajima and Hirose 28 – Reference Yu, Hsieh and Wang 30 ). A total of 6627 patient cases were involved with sample sizes ranging from 400 to 199 748, ages ranging from 18 to 80 years and observation periods ranging from 5 months to 19 years. The related factors adjusted for included age, gender, smoking and alcohol consumption (Table 1).

Table 1 Characteristics of studies included in the current meta-analysis of associations of green tea and risk of gastric cancer

NA, not available; M, male; F, female; HB, hospital based; PB, population based.

* Case–control studies.

† Cohort studies.

Quality assessment

The quality of the included studies was assessed using the NOS. The scores of the cohort studies were relatively high, with scores of 7–9 for all five studies that were considered high quality. For the case–control studies, the NOS score of one study fell in the range of 0–6 (low quality), whereas the other seven studies scored 7–9 (high quality; see online supplementary material, Table S2).

High v. low intake meta-analysis

All five cohort studies were included in the correlation analysis of the high v. low dose of green tea and the risk of gastric cancer( Reference Nechuta, Shu and Li 19 , Reference Hoshiyama, Kawaguchi and Miura 22 , Reference Tsubono, Nishino and Komatsu 24 , Reference Nagano, Kono and Preston 25 , Reference Galanis, Kolonel and Lee 27 ). The pooled relative risk was 1·05 (95 % CI 0·90, 1·21), with low evidence of heterogeneity (I 2=20·3 %, P=0·286). There was no significant correlation between green tea and gastric cancer (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Meta-analysis of high v. low dose of green tea and risk of gastric cancer for cohort studies by using fixed-effects model (a) and random-effects model (b). The study-specific relative risk (RR) and 95 % CI are represented by the black dot and horizontal line, respectively; the area of the grey square is proportional to the specific-study weight to the overall meta-analysis. The centre of the open diamond and the dotted vertical line represent the pooled RR; the width of the diamond represents the pooled 95 % CI

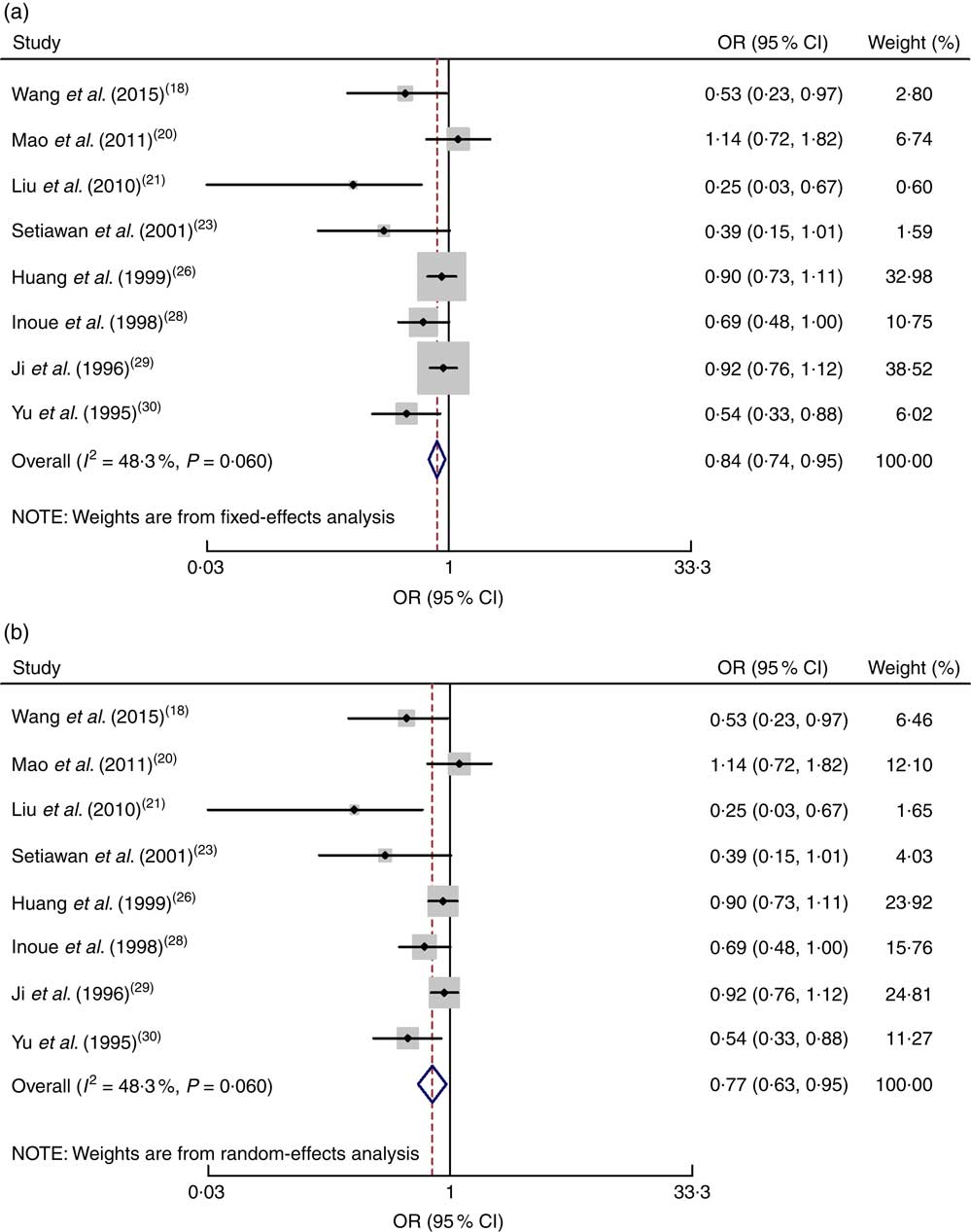

All eight case–control studies were included in the correlation analysis of the high v. low dose of green tea and the risk of gastric cancer( Reference Wang, Duan and Yang 18 , Reference Mao, Jia and Zhou 20 , Reference Liu, Zhao and Zhang 21 , Reference Setiawan, Zhang and Yu 23 , Reference Huang, Tajima and Hamajima 26 , Reference Inoue, Tajima and Hirose 28 – Reference Yu, Hsieh and Wang 30 ). The pooled relative risk was 0·84 (95 % CI 0·74, 0·95) with moderate evidence of heterogeneity (I 2=48·3 %, P=0·060). Drinking a high dose of green tea reduced the risk of gastric cancer by 26 % (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Meta-analysis of high v. low dose of green tea and risk of gastric cancer for case–control studies by using fixed-effects model (a) and random-effects model (b). The study-specific OR and 95 % CI are represented by the black dot and horizontal line, respectively; the area of the grey square is proportional to the specific-study weight to the overall meta-analysis. The centre of the open diamond and the dotted vertical line represent the pooled OR; the width of the diamond represents the pooled 95 % CI

Non-linear dose–response analysis

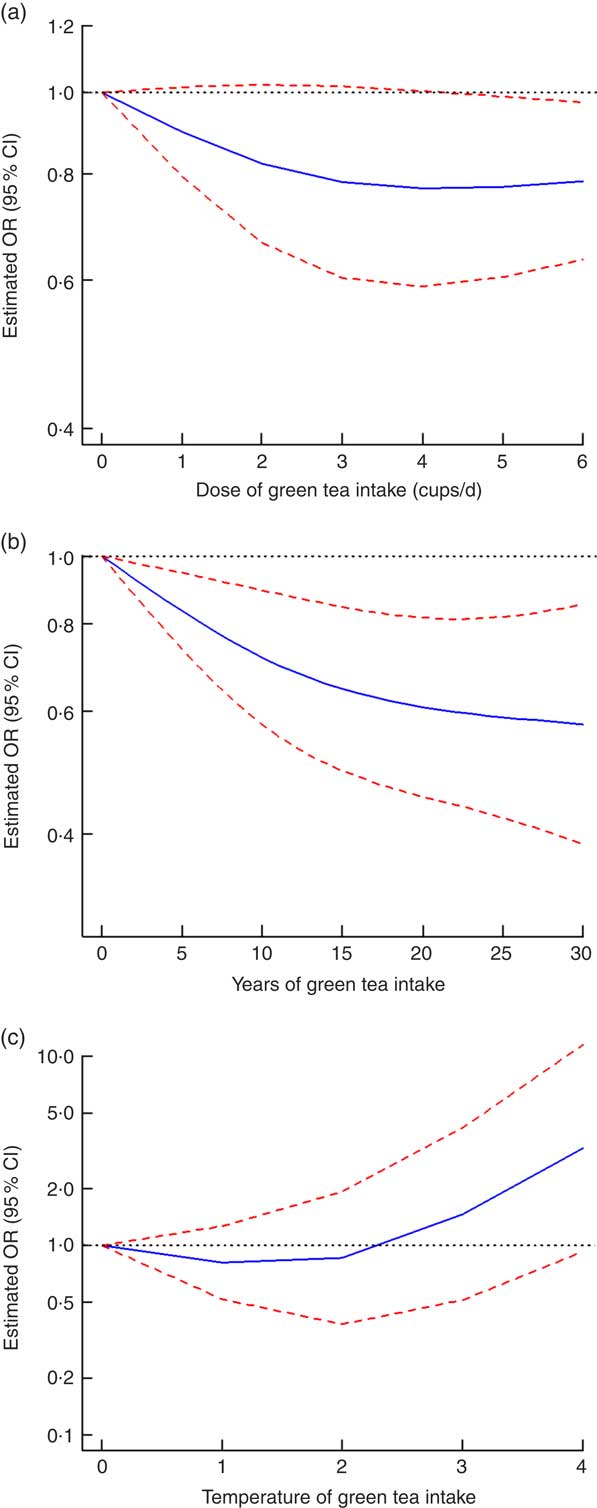

All eight case-control studies were included in the non-linear dose–response analysis for the dose of green tea intake and the risk of gastric cancer( Reference Wang, Duan and Yang 18 , Reference Mao, Jia and Zhou 20 , Reference Liu, Zhao and Zhang 21 , Reference Setiawan, Zhang and Yu 23 , Reference Huang, Tajima and Hamajima 26 , Reference Inoue, Tajima and Hirose 28 – Reference Yu, Hsieh and Wang 30 ). When the green tea intake was 4 cups/d or less, no non-linear relationship between the intake of green tea and the risk of gastric cancer was found (OR=0·77, 95 % CI 0·59, 1·00, I 2=63·8 % for 4 cups (approximately 4 g) of green tea intake daily). However, when the intake of green tea was 4–6 cups/d, the risk of gastric cancer was lower (OR=0·79, 95 % CI 0·63, 0·97, I 2=63·8 % for 6 cups (approximately 6 g) of green tea intake daily; P=0·15 for non-linearity; Fig. 4(a)).

Fig. 4 Non-linear dose–response relationship between dose (a), years (b) and temperature (c) of green tea intake and the risk of gastric cancer: ![]() , best-fitting fractional polynomial;

, best-fitting fractional polynomial; ![]() , 95 % CI. For temperature of green tea intake, 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4 represent undrinkable, cool, warm, hot and very hot, respectively

, 95 % CI. For temperature of green tea intake, 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4 represent undrinkable, cool, warm, hot and very hot, respectively

One cohort study( Reference Nechuta, Shu and Li 19 ) and two case–control studies( Reference Liu, Zhao and Zhang 21 , Reference Setiawan, Zhang and Yu 23 ) were included in the non-linear dose–response analysis for the years of green tea intake and the risk of gastric cancer. There was a non-linear dose–response relationship between the years of green tea intake and the decrease in the risk of gastric cancer incidence with 25 years of green tea intake (OR=0·59, 95 % CI 0·42, 0·82, I 2=1·0 % for 25 years of green tea intake; P=0·13 for non-linearity; Fig. 4(b)).

Three retrospective studies( Reference Wang, Duan and Yang 18 , Reference Mao, Jia and Zhou 20 , Reference Yu, Hsieh and Wang 30 ) were included in the non-linear dose–response analysis for the temperature of green tea intake and the risk of gastric cancer. The impact of the green tea drinking temperature on the risk of gastric cancer was not conclusive, but the risk of gastric cancer showed a rising trend with the increase in the green tea drinking temperature (P=0·022 for non-linearity; Fig. 4(c)).

Publication bias

The publication bias of the included studies was assessed using Begg’s test and Egger’s test. For the cohort studies, the results of Egger’s (P=0·767) and Begg’s tests (P=0·806) were not significant. For the case–control studies, the results of Egger’s (P=0·025) and Begg’s tests (P=0·108) were also not significant (see online supplementary material, Fig. S1).

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis investigating the influence of each single study on the gastric cancer risk estimate suggested that the risk estimates were not substantially modified by any single study (see online supplementary material, Fig. S2).

Discussion

In the present meta-analysis, the results of the case–control studies showed that the consumption of a high dose of green tea could reduce the risk of gastric cancer. Based on the dose–response analysis, the risk of gastric cancer showed a gradual decreasing trend with increase in the consumption of green tea; additionally, we found a lower risk of gastric cancer associated with a longer tea drinking experience.

Previous experiments demonstrated that the polyphenols in green tea had antioxidant effects and could suppress the occurrence and development of cancer( Reference Wang, Wang and Wan 4 – Reference Zhong, Huan and Cao 6 ). At the cellular level, tea polyphenols can inhibit the growth, reproduction and diffusion of cancers( Reference Qiao, Gu and Shang 40 ). Additionally, several studies reported that H. pylori infection was an important risk factor for gastric cancer( 41 ). Importantly, green tea has been shown to possess bacteriostatic and bactericidal effects that reduce the occurrence of gastric cancer caused by H. pylori infection( Reference Jeong, Park and Han 42 ). However, the combined results of the cohort studies in the present meta-analysis showed that high doses of green tea still cannot be considered to reduce the risk of gastric cancer. Similarly, Galanis et al.( Reference Galanis, Kolonel and Lee 27 ) believed that drinking green tea might not have an effect on the risk of gastric cancer, although this result might have been obtained because an effective dose was not reached (≥2 cup/d for the highest dose group in that study) or the number of cases was too small. Additionally, Tsubono et al.( Reference Tsubono, Nishino and Komatsu 24 ) obtained the same conclusion that the consumption of green tea had no impact on the risk of gastric cancer. However, our meta-analysis of the case–control studies indicated that the consumption of a high dose of green tea could reduce the risk of gastric cancer. The studies conducted by Kono et al., Inoue et al. and Liu et al. showed that exposure to high doses of green tea had a certain impact on the incidence of gastric cancer( Reference Liu, Zhao and Zhang 21 , Reference Inoue, Tajima and Hirose 28 , Reference Kono, Ikeda and Tokudome 31 ). Kono et al.( Reference Kono, Ikeda and Tokudome 31 ) believed that the consumption of a high dose of green tea (≥10 cups/d) could reduce the risk of gastric cancer. In their study, a community group in the same area as the hospital-based group was used as the control, and the study subjects from the hospital were surveyed before the diagnosis to reduce recall bias. These case–control studies( Reference Liu, Zhao and Zhang 21 , Reference Inoue, Tajima and Hirose 28 , Reference Kono, Ikeda and Tokudome 31 ) included larger sample sizes. Nevertheless, the cohort studies and the case–control studies had different combined results. One possible reason was that the period of green tea exposure was too short or the dose of exposure was too low for the surveyed subjects in the cohort studies.

In Japan, the largest green tea production area is Shizuoka prefecture. A survey found that mortality due to gastric cancer in the local residents of this area was much lower than the average in Japan, which was inferred to be related to green tea consumption by the local residents. Additionally, the local residents not only drank green tea frequently but also frequently replaced the green tea with new tea leaves when drinking, and their history of green tea consumption was very long. Therefore, the reduction of the risk of gastric cancer may be closely related to the dose of the active ingredient in green tea and the length of tea exposure( Reference Oguni, Kanaya and Ota 43 ). The present meta-analysis found that when the green tea exposure was in a low dose (≤4 cups/d), its protective effect on gastric cancer was not obvious; however, when the exposure dose was higher than 5 cups/d, its protective effect on gastric cancer gradually increased. Wang et al. reported that when the green tea exposure was ≥35 g/month (approximately 5 cups/d), the risk of gastric cancer decreased( Reference Wang, Duan and Yang 18 ). Additionally, a previous systematic review reported that the intake of a high dose of green tea was a protective factor for the reduction of gastric cancer( Reference Huang, Wang and Shen 44 ). These findings are consistent with the results of the current meta-analysis. In subjects with a prolonged history of tea consumption, a longer history of green tea exposure had a stronger protective effect on gastric cancer. Liu et al.( Reference Liu, Zhao and Zhang 21 ) reported that the risk of gastric cancer was decreased with increasing time of green tea consumption. Studies have confirmed that long-term exposure to polyphenols could help improve the oxidative state of the body, scavenge free radicals, improve local chronic inflammation and regulate the digestive tract microenvironment, thereby contributing to the reduction of the risk of gastric cancer( Reference Riegsecker, Wiczynski and Kaplan 45 – Reference Kim, Formoso and Li 47 ). Notably, the present meta-analysis found that when the temperature of the tea was too high, the occurrence of gastric cancer could even be promoted with a certain dose–effect relationship. Previous studies have reported that long-term consumption of food at a high temperature might damage the digestive tract mucosa, causing related diseases( Reference Goldman and Schafer 10 ). However, whether high temperatures will lead to gastric cancer needs to be confirmed by further studies with large sample sizes.

Other systematic reviews

Some systematic reviews of tea and gastric cancer exist. First, Zhang et al.( Reference Zhang, Xu and Lu 48 ) included only prospective studies investigating the dose–response association between tea consumption and the incidence of cancer (gastric cancer, rectal cancer, colon cancer, lung cancer, etc.). Their study indicated that increased tea consumption is associated with a reduction in the risk of oral cancer but has no significant effect on the risk of other common cancers. Second, Sasazuki et al.( Reference Sasazuki, Tamakoshi and Matsuo 49 ) investigated green tea consumption and gastric cancer risk (incidence and death) among the Japanese population and performed a meta-analysis which included case–control studies and cohort studies. The conclusion was that green tea possibly decreases the risk of gastric cancer in women. Additionally, Boehm et al.( Reference Boehm, Borrelli and Ernst 50 ) conducted a meta-analysis of green tea for the prevention of cancer, including case–control studies, cohort studies and randomized controlled trials. They found moderate to strong evidence that green tea consumption does not decrease the risk of dying due to gastric cancer. Finally, Borrelli et al.( Reference Borrelli, Capasso and Russo 51 ) published a systematic review of the association between green tea and gastrointestinal cancer risk in which cross-sectional studies, case–control studies and cohort studies were included. They concluded that an inverse association does not seem to exist between green tea consumption and the risk of gastric and intestinal cancer. Additionally, their study found that the effect of green tea is related to the method of preparation and its strength and temperature, which should be considered in future epidemiological investigations.

Compared with previous meta-analyses, our meta-analysis has some obvious differences. First, herein, we analysed not only the relationship between drinking green tea and the risk of gastric cancer, but also the relationship between the duration (years) of drinking green tea and the temperature of green tea and the risk of gastric cancer. Moreover, we analysed the dose–response relationship to understand the risk of gastric cancer at different levels of exposure. Finally, the exposure factor in our meta-analysis review was green tea, a specific type of tea; thus, the results were more specific, reducing the level of heterogeneity.

Limitations

The present study has some limitations. First, the scope of the included studies was limited and the research locations were mostly in East Asia, including China and Japan; thus, the study subjects were mostly an Asian population. Second, the original studies reported the tea dose in the unit of ‘cups’, from which the dosage of the active ingredient in green tea could not be determined. Third, we may have missed some studies because the database searches were limited. Some publication bias may exist in the included case–control studies. Additionally, adjustment for other involved risk factors was limited in the included studies, and some bias might have occurred in their reported risk values. Finally, there are some confounding factors in our study. Different follow-up periods of included studies may lead to a difference in the incidence of gastric cancer and thus have an impact on the true relationship between exposure and outcome. In addition, differences in year of publication lead to updates in research methods, improvements in detection methods and changes in dietary habits, resulting in differences in outcome accuracy.

Implications

The present meta-analysis has important implications for further studies on green tea and gastric cancer risk. In subsequent observational studies, the corresponding study of different races should be increased, the units for measuring tea drinking should be taken into account and the follow-up period should be clearly defined. For the following basic research, we can focus on the effect of tea polyphenols (main active components in green tea) on gastric cancer. In addition, such study can provide a basis for the tea-drinking habits of people, and provide a reference for the production of appropriate nutritional supplements. In the absence of clear evidence answering questions about the right amount, duration (years) and temperature of green tea intake, further high-quality studies are needed to make concrete public recommendations.

Conclusion

In summary, long-term and high-dose consumption of green tea may be associated with a reduced risk of gastric cancer. In addition, drinking too-high-temperature green tea may be associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer, but it is still unclear whether high-temperature green tea is a risk factor for gastric cancer. However, the duration of follow-up in uncertain, which raises concerns regarding the precision of our analysis. Additional research including large-scale pooling and high-quality studies will be needed to confirm our conclusions.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC; grant number 81473068) and the National Social Science Foundation (China) (NSSF; grant number 14BTJ019). The NSFC and NSSF had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: Y.H.H. and H.R.C. contributed equally to this work. Y.H.H. and L.Z. conceived the study. Y.H.H. and H.R.C. searched the databases and checked them according to the eligibility and exclusion criteria. L.Z. helped develop search strategies. L.Z. gave advice on meta-analysis methodology. G.M.L. helped extract quantitative data from some papers. Y.H.H., H.R.C. and L.Z. analysed the data. Y.H.H. wrote the draft of the paper. Y.H.H., H.R.C., L.Z., G.M.L. and D.L.Y. contributed to writing, reviewing or revising the paper. All authors approved the final version. D.Y. is the guarantor. Ethics of human subject participation: Ethical approval was not required.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017002208