Local governments have traditionally been involved in activities related to the food and nutrition system. Food safety and trade, land use for agriculture and horticulture, monitoring food retail premises and provision of food to low-income and unemployed communities have been some of the activities of local governments(Reference Yeatman1). In Australia, the National Food and Nutrition Policy (1992) specifically highlighted the important role local governments play in the food system(2). As part of that policy, selected local governments were provided with support to develop local food and nutrition policies, with varying success(Reference Yeatman1). In North America, food policy councils have been an important local focus for community food issues(3). More recently, country-level obesity-related and food insecurity concerns have again focused on the roles of local governments in the food system(4, 5).

Local governments have different roles and responsibilities and also different capacities to undertake food-related activities. In Australia, local governments are an extension of state governments. While they have their own elected members who represent their local communities, their capacities to take independent actions are constrained and directed by state governments. They do not have extensive power to raise revenues, as land taxes are capped by state legislation, and they are also required to meet certain obligations linked with state distributed-funds(Reference Colebatch and Degeling6). Some of these obligations may enhance their capacity to impact local food systems, such as mandatory requirements to develop Municipal Public Health Plans(7), while other obligations may limit their capacities to act.

State governments vary in their positions and support for the roles local governments are expected to fulfil in relation to food and nutrition. In the state of Victoria, the Victoria Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth) has taken an increased interest in the role of local government in supporting food issues, particularly as they relate to food security. Funds have been provided directly to local governments to provide local initiatives. This support is within a broader framework engaging local governments in community-based health initiatives. In the early 1990s, six healthy localities were funded to implement initiatives using the principles of the WHO Healthy Cities programme. This action was subsequently extended in 2001 with the mandating of Municipal Public Health Planning based on a social view of health(Reference de Leeuw, Butterworth, Garrad, Palermo, Godbold and Tacticos8). Broader, state-level food system initiatives have also been a focus in this state and support networks have been established to facilitate on-going food system actions by local governments(9–12). In New South Wales (NSW), selected local governments have led the way in local food system actions since the early 1990s(Reference Yeatman13), with Penrith Food Policy Council(Reference Webb14), South Sydney Food and Nutrition Policy(Reference Hodge and Finlay15) and the Hawkesbury Food Programme(Reference Saville16) being particularly well known. More recently, the NSW Food Authority has developed a partnership with local governments to boost initiatives in the area of food safety(17) and the NSW government has supported eighteen resolutions involving local government action that resulted from a childhood obesity summit in 2002(18). In recent times, Queensland Health has also stimulated local governments to be involved in food activities via their Eatwell initiatives(19).

The impact of this focus on the roles of Australian local governments in nutrition and food-related initiatives is yet to be assessed. Evaluations of individual projects have been published(20) and some work undertaken in understanding the development of food and nutrition policies within local government(Reference Webb14, Reference Hodge and Finlay15, Reference Dick21, Reference Yeatman22) but little is known of the overall impact on the activities undertaken by Australian local governments. Are they more engaged in food and nutrition activities now than in the past? Are nutrition or food activities considered by managers and/or staff as strategically important components of local government’s activities?

A snap shot of food and nutrition activities of Australian local governments was undertaken in 1995 to determine their involvement in twenty-nine aspects of food and nutrition(Reference Yeatman1, Reference Yeatman22). In January 2007, this survey was repeated. The aim was to determine the current level of local food and nutrition action and whether the level had changed between 1995 and 2007.

Methods

A cross-sectional study utilising a postal survey was undertaken of all local governments in Australia. Ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Wollongong (HE06/350).

The protocol for the study, including the survey instrument, replicated a study undertaken in 1995(Reference Yeatman1). The survey instrument, covering letter, contact details form and envelope were sent to the General Manager of each local authority requesting that s/he pass on the survey instrument to an appropriate person in the Environmental Health Services. A date, 2 weeks from that time, was nominated for return of the survey. Reminder letters were sent 1 week after the return date had expired. The time period was January–March 2007.

A list of 665 local governments was developed, based on the information on the Australian Local Government Association (ALGA) website. This compared with 742 local governments covered in 1995. The difference had resulted from a number of mergers and consolidations that had occurred in local governments in the 11-year period between surveys. The study analysis was restricted to 610 local governments, with the exclusion of the Northern Territory and Australian Capital Territory local governments, which are constituted differently from local governments elsewhere in Australia. These criteria for data analysis were also applied in the report of the survey in 1995.

The survey instrument

The survey instrument was based on known involvements of local governments at the time of the original survey, 1995. Information was collected from reports of local governments, review of local food policy councils and personal communications with staff. The framework was based on Lester’s 1994 overview of the Australian food and nutrition system(Reference Lester23).

Part A of the survey instrument was designed to determine the extent to which local governments were involved in twenty-nine different aspects of the food system, broadly grouped under eight topics (left-hand column, Table 1). The survey included closed- and open-ended questions, to promote the ease of response while maximising the useful information. ‘Yes’ responses included three categories (‘Yes, Council has in the past’; ‘Yes, Council has in the present’; ‘Yes, Council plans to in the future’). This was followed by open-ended questions requesting information on the department within the local government responsible for the implementation of the programme and the name or description of the project. A ‘No’ response was followed by an open question requesting reasons for non-involvement. It was suggested that the Environmental Health Officer may be the best person to answer the survey but s/he may find it necessary to refer to other staff for answers to particular questions. Next to specific groups of questions, prompts were included in the survey to suggest the responding staff person or a particular department to whom to refer for relevant information.

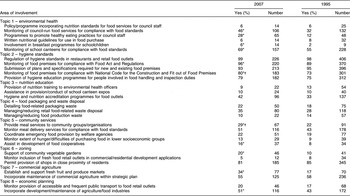

Table 1 Involvement of Australian local governments in the twenty-nine listed food and nutrition activities, 2007 and 1995

*Significant difference between percentage of local governments reporting activity in this area between 1995 and 2007 (χ 2, P < 0·05).

†Difference no longer significant when 2007 data excludes Victorian local governments.

Part B of the survey requested demographic data to identify the position of the person completing the survey, the geographic location of the local government and its population base. Additional questions sought responses on the perceived role of local government in relation to a number of possible food-related activities. These questions used a Likert-type scale for the responses.

A specific attitudinal question was asked of the General Manager to designate where s/he would place food issues as a priority for consideration by Council in strategic planning. Copies of annual reports, strategic plans and relevant policy documents also were requested.

Data analysis

Coding of the completed surveys was undertaken as they were received. The open-ended responses were individually coded using the same codes as the original survey analysis. The coding of rural and urban local government was based on information on the ALGA website(24).

The data were entered into Excel (Microsoft® Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) and then transported to the Statistical Analytical Software (SAS) package release 8·2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) for analysis. Descriptive analyses using χ 2 tests were undertaken.

Results

The overall response rate for the 2007 survey was 37 %, with a spread across the states that was not significantly different from the distribution of local governments in Australia but with a variation in response rate for each state, from 26 % to 48 % (Table 2; row 1). Overall 50 % of all urban local governments in Australia responded and 30 % of all rural local governments responded.

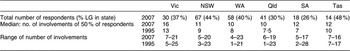

Table 2 Involvement in food and nutrition activities by local government in different states

Vic, Victoria; NSW, New South Wales; WA, Western Australia; Qld, Queensland; SA, South Australia; Tas, Tasmania; LG, local government.

Table 1 presents the involvement of local governments in the twenty-nine different food and nutrition activities, both in 1995 and in 2007. Those activities reported by most local governments were related to monitoring hygiene standards, activities mandated by state law in most states. Lowest levels of reported involvements were found for areas of discretionary involvement for local governments such as nutrition education, food packaging and waste disposal and some aspects of zoning.

The results reported in Table 1 indicate the general trends in activity by local governments in food and nutrition activities over the 11-year period. In twelve areas of activity, local governments were significantly more active in 2007 than in 1995. In nine areas, the levels of reported activity decreased but the change was not statistically significant. In eight areas, there was basically no change in the level of reported activity. In two areas, monitoring of premises for compliance with the National Code and provision of meal services to community groups/organisations, the increase in activity in 2007 for all local governments was no longer significant when the Victorian local governments were removed from the analysis.

In some areas, such as monitoring premises for compliance with the Food Act and Regulations, improvement was from an already high level of involvement (89 % in 1995, increasing to 96 % in 2007). However, in other areas, while the improvement was statistically significant, it still represented a low level of activity reported by local governments. For example, involvement in support for community vegetable gardens increased from 10 % to 20 %, and involvement in breakfast programmes for schoolchildren increased from 2 % to 6 %.

Local governments consistently reported high levels of activity (at least 75 % of local governments responded yes) in the monitoring of hygiene standards and with zoning of shops in close proximity to residents. Local governments across Australia reported low levels of activity (less than 25 % of local governments responded yes) in almost half of the food and nutrition areas (thirteen of the twenty-nine areas reported low levels of activity). The pattern of high and low levels of activity was similar in both 1995 and 2007.

All states reported at least some involvement in some of the twenty-nine food and nutrition activities, with the minimum number of involvements increasing from one activity to four activities over the period of the two surveys (Table 2). There was a trend for the overall involvement of local governments in food and nutrition initiatives to increase in the period 1995–2007, from a median of nine activities to a median of eleven activities. This trend was evident in each state. However, the range of involvements of local governments in food and nutrition activities had become more limited (maximum of twenty-three of twenty-nine activities) than in 1995 (up to twenty-eight of twenty-nine activities), representing an overall constriction of the range of activities of local government in food- and nutrition-related initiatives.

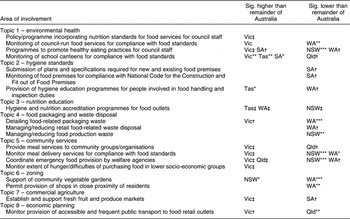

There was some variation in the levels of activity in the different states (Table 3). Victoria was particularly worth noting, as it was significantly more active than the rest of Australia in ten areas of activity, particularly in the areas of environmental health and community services. States that were significantly less active than the rest of Australia were Western Australia (ten areas less active) and NSW (five areas less active).

Table 3 Involvement of Australian local governments in the twenty-nine listed food and nutrition activities, 2007

Sig., significantly; Vic, Victoria; NSW, New South Wales; WA, Western Australia; Qld, Queensland; SA, South Australia; Tas, Tasmania.

χ 2, *P = 0·05; **P < 0·05; ***P < 0·02; †P < 0·01; ‡P < 0·001.

In response to the question of the General Manager, how important do you consider that food-related matters should be considered in the strategic planning process, both in 1995 and in 2007 approximately 40 % responded that food issues were very important or essential. The responses in the different states varied, with Western Australian General Managers reporting higher levels of importance in 1995 and Victorian General Managers reporting higher levels of importance in 2007 (Table 4).

Table 4 Reported importance of considering food-related issues during the strategic planning process, as rated by the General Manager. State v. rest of Australia

Vic, Victoria; NSW, New South Wales; WA, Western Australia; Qld, Queensland; SA, South Australia; Tas, Tasmania.

*Vic v. rest of Australia, 2007: χ 2, P = 0·03.

**WA v. rest of Australia, 1995: χ 2, P = 0·03.

Staff were asked to rate their perceived importance regarding local government involvement in several food and nutrition areas (Table 5). Both in 1995 and in 2007, staff in Victoria rated several areas to be of high importance for local government involvement – nutrition education in schools (also rated more highly by local government staff in South Australia), food accessibility of aged and infirmed residents, food retail locations in relation to residential areas and nutritious foods available through the retail sector (2007 only). In contrast, NSW and Queensland local government staff rated involvement in several food areas to be of lower importance. Queensland staff rated food accessibility of aged and infirmed residents and food retail locations in relation to residential areas lowly in 1995 but were no different from the rest of Australia in 2007 for these two areas. However, in 2007, Queensland staff rated maintenance and promotion of primary food production to be of lower importance for local government involvement than the rest of Australia. Staff in NSW local governments were no different from the other states in 1995, but in 2007 they rated four areas of involvement to be of lower importance.

Table 5 Perceived importance of involvement of local governments in various food-related issues – staff response

Vic, Victoria; NSW, New South Wales; WA, Western Australia; Qld, Queensland; SA, South Australia.

*χ 2, P = 0·01 or less; **χ 2, P = 0·001 or less.

***Nutrition education in schools decreased across Australia between 1995 and 2007.

Discussion

There is clear evidence that both local communities and other spheres of government are demanding more from local government.(25)

Local governments in Australia have been in an on-going state of change and under resource pressure due to conflicting demands on their services. The present study has provided some insight into the impact that these pressures, together with other supportive initiatives, has had on local government involvement in food and nutrition initiatives. A broad view of possible local government involvement in the local food and nutrition system was applied.

The results obtained in the present study could be considered indicative of local governments across Australia as the responding local governments reflected the national distribution of local governments across the states. The lower response rate in 2007 may reflect a number of issues. Lower priority may be assigned to food and nutrition issues in local government, in which case the results may be an overestimation of local government involvements. Alternatively, there may be less staff available to participate in a study such as this, reflecting the greater demands being placed on local government resources or organisational issues affecting the access to the survey by relevant staff. However, a response rate of 37 % is not unusual for recent population surveys(Reference Angove, Cresswell, Akhtar, Rolfe, Brooksbank and Thomas26–Reference Simpson, Emmerson, Frost and Powell30) and it may be that the 1995 survey reflected a higher than expected response.

Simple comparisons of local governments in one state with other states or between rural and urban local governments may not provide an accurate reflection of the situation. For example, the Victorian data may be strongly influenced by the greater proportion of urban local government respondents. Forty-five per cent of urban local governments in Victoria responded to the survey compared with only 14 % of rural local governments in Victoria.

The survey instrument itself, based on a 1994 schema of the food and nutrition system, was considered to provide an appropriate framework for considering local government involvements, as there were no significant changes in their designated roles and responsibilities during the period 1995–2007. Contemporary discussions concerning the potential roles of local governments in relation to obesity issues(Reference King, Kavanagh, Jolley, Turrell and Crawford31, Reference Sanigorski, Bell, Kremer, Cuttler and Swinburn32) were considered to be preliminary at the time of this survey but could be considered in the future.

In 2007, local governments were involved in a smaller total number of food and nutrition activities compared with their activity in 1995; however, levels of activity significantly increased in twelve areas. This may indicate that local governments recognise the importance of their involvement in food issues but they need to consolidate such activity due to resource constraints. Alternatively, it may indicate that there are certain areas of food and nutrition activity that are mandated or for which they are provided resources or support.

The areas of involvement consistently reported by local governments across Australia were in the monitoring and enforcement of food hygiene-related activities. The only other high-level involvement for Australian local governments was the permission of retail outlets in close proximity to residents. Even in these areas of involvement, not all responding local governments were active. Informal feedback from respondents identified that for small shires, regulatory activities were undertaken by larger local governments within a broader geographic area, who may cover several small shires. Another mechanism reported from a respondent was local health services undertaking the food regulation and monitoring role of five urban local governments. Since this survey was conducted, NSW local governments have been required to designate their level of engagement in the monitoring and enforcement of food hygiene-related activities, with the lowest of the three levels being no involvement(33).

The variation of activity areas of local governments in the different states provides support for the notion that State governments may have particular expectations and/or provide support for local government action, in particular food and nutrition areas. In Victoria, local governments are clearly more active than the remainder of Australia across a number of food areas. This may be a result of support and incentives provided by VicHealth (a health promotion foundation supported by government funds) for local government engagement(20) or the mandatory requirement for Municipal Public Health Plans(34). The Food Security Network also proactively supports local governments in their food and nutrition roles(9). However, as Victoria also was more active in several food and nutrition areas in 1995, which preceded these initiatives, it would be worthwhile to investigate other supportive factors that have been in place prior to this time.

Commitment within the organisation drives the allocation of resources and may account for some of the differences in activity levels reported. General Managers of local governments in Victoria in 2007 were significantly more likely to rate food and nutrition more important in the strategic planning process than other states. Staff in Victorian local governments were also significantly more likely to rate several food issues as important areas of activity for local governments. This finding, that in the state with higher levels of reported activity more staff rated food issues as important, is consistent with the finding of Dick(Reference Dick21) that local government employees need to understand how food and nutrition policy can assist them to undertake their roles and fulfil the core business of Council if they are to engage in development (and implementation) of food and nutrition activities(Reference Dick21).

The trend for NSW and Western Australia to report significantly lower levels of involvement in several areas of activity than the remainder of the Australian states is a possible area of concern. For Western Australia, this is also accompanied by a change in General Managers’ views of the importance of including food and nutrition activities in strategic planning, which was significantly higher in 1995 than other General Managers in Australia and changed to being no different in 2007. Local government staff in NSW were significantly less likely to rate several food and nutrition issues of importance for local government involvement than other states. This is despite the pioneering involvement of several local governments in food and nutrition policy initiatives over the last 15 years. Activities may align with personal interests of staff and/or are reflective of local community circumstances, and it cannot be assumed that they will be taken up by other local governments over time.

These patterns of activity are interesting for several reasons. The recently introduced requirement in NSW for local governments to nominate their level of involvement in monitoring and enforcement of food regulations occurred after the 2007 survey was conducted. Thus it is unlikely to have been a factor in these results. However, limited support from staff for local government involvement in food and nutrition activities, as found in this survey, may act as a barrier to the implementation of the new laws. The present survey may act as a baseline against which the impact of this new legislation may be monitored.

In Western Australia, the reduction in attitude of General Managers toward importance of food and nutrition issues in strategic planning is likely to have contributed to the lower levels of activity reported by local governments in that state. What led to this turnaround is uncertain. Informal feedback from some local government staff indicated that significant constraints had been imposed on local governments, allowing only the very core services to be offered. Conversely, another local government in Western Australia reported quite high levels of involvement across a range of food and nutrition areas, facilitated by joint initiatives with an academic institution. These different accounts reinforce the arbitrary/voluntary nature of many food and nutrition activities within local government.

The variation in local governments’ involvements in the food and nutrition activities by the different states may result from various factors. Preliminary review of the factors reported by respondents in this survey included lack of funding, lack of resources and ‘not a priority’ as key issues. Another factor may be that activities conducted by local governments in some states are undertaken by other departments or organisations in different states. Alternatively, there may be food and nutrition responsibilities that are not being met in some states. More in-depth study of the factors behind these differences in reported activity levels between the different states is warranted, to identify barriers and incentives that have impacted on local governments’ involvements in the food and nutrition system.

Conclusion

Local governments in Australia continue to be engaged in food and nutrition activities. This involvement has constricted in range in the last 12 years but higher levels of engagement are reported for several areas. The levels of involvement of local governments in the different states varied significantly, with Victoria reporting higher levels of involvement in several areas, particularly in food and nutrition activities related to community services. Local governments in NSW and Western Australia reported significantly lower levels of involvement in food and nutrition activities. The reasons for these differences were not the focus of the present study; however, several factors may have contributed, including availability of resources and support, mandatory requirements by state governments, different attitudes of General Managers and staff, and availability of funds for special projects. If Australian local governments are to be recognised and supported for their involvements in food and nutrition activities, more in-depth research is required to elucidate the factors that act as barriers or facilitate their on-going involvement in this important area. Special consideration should be given to more in-depth research into the situation of rural local governments, with a view to identifying the necessary support and resources required to become or remain engaged in food matters.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: Partial financial support to conduct the 2007 survey was provided by VicHealth, a not-for-profit statutory agency.

Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

Author’s contributions: The work was undertaken by Yeatman as part of her academic role at the University of Wollongong. D. Sinikovich provided administrative research assistance and V. Kendrick provided data entry and statistical support.

Acknowledgements: The manuscript has a sole author, Yeatman, responsible for 100 % of the article.