With the rapid increase in the elderly population that has been observed in recent decades, functional disability is a major concern in relation to health and care demand. The presence of disabilities is associated with higher health-care needs and utilization compared with those with no disability, including recurrent hospitalization, greater use of outpatient care and increased risk of falls, injuries and acute illnesses( Reference Fried and Guralnik 1 , Reference Chatterji, Byles and Cutler 2 ). This is an even greater concern in developing countries, since their demographic transition occurs faster and health services are not prepared to receive this growing demand( Reference Prince, Wu and Guo 3 ). Moreover, a rapid process of nutritional transition is ongoing in developing countries, with an increasing obesity and a still high proportion of underweight, which has a considerable impact on health-care services( Reference Corona, Pereira de Brito and Nunes 4 ).

Excess weight and obesity have been associated with a number of co-morbidities in all phases of life, especially chronic, non-transmittable conditions( Reference Bray 5 , Reference Zamboni, Mazzali and Zoico 6 ). But in recent years, several studies have demonstrated that obesity is associated with limitations regarding physical function, independently of the presence of disease( Reference Corona, Pereira de Brito and Nunes 4 , Reference Jensen and Friedmann 7 – Reference Verbrugge, Gates and Ike 13 ). However, some results are not clear regarding obesity and disability. In a study carried out in the USA, class I obesity (BMI from 30 to 34·99 kg/m2) proved to be a protective factor against disability in men( Reference Imai, Gregg and Chen 14 ). Nevertheless, several authors suggest that BMI high values are associated with increased bone mineral density and decreased osteoporosis and hip fracture in older men and women: the increase in bone mineral density and the extra cushioning around the trochanter (outer prominence of the femur) might provide protection against hip fracture during a fall in obese older persons( Reference Villareal, Apovian and Kushner 15 – Reference Felson, Zhang and Hannan 17 ), and thus could be protective against functional limitation after the fall.

The use of BMI is controversial in older adults. According to many authors, analysing only body weight may be a mistake, because changes in body composition may mask the real nutritional status, especially muscle wasting and fat distribution( Reference Hickson 18 – Reference Cook, Kirk and Lawrenson 21 ). Moreover, several authors have pointed out that a BMI cut-off point of 25 kg/m2 may be overly restrictive for older adults and have suggested that this threshold should be raised( Reference Janssen 22 , Reference Lipschitz 23 ). Some different, more conservative, cut-offs were proposed in the literature; the most known are the one proposed by Lipschitz( Reference Lipschitz 23 ), with an optimal range between 22 and 27 kg/m2, and the one proposed by the American Committee on Diet and Health( Reference Ham 24 , Reference Beck and Ovesen 25 ), between 24 and 29 kg/m2.

The main problem is that obesity should be defined as the amount of excessive fat storage and although BMI is a well-accepted surrogate of body fat, body composition changes may influence its use in older adults because both weight and height may be modified with ageing. The decrease in fat-free mass and increase in fat mass, combined with height loss caused by the compression of vertebral bodies, alter the relationship between BMI and percentage body fat. In addition, there is a higher relative increase in intra-abdominal fat than in subcutaneous or total body fat with ageing( Reference Zamboni, Mazzali and Zoico 6 , Reference Villareal, Apovian and Kushner 26 , Reference Mankowski, Anton and Aubertin-Leheudre 27 ).

Therefore, it is important to understand if the higher risk of disability can be due to weight in general or to a higher fat concentration. The second situation can be very common in older adults with ‘normal’ weight, considering those changes in body composition with ageing. For instance, a study in the adult population (20–79 years) of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) showed that about 30 % of men and 69 % of women with BMI in the normal range had abdominal obesity( Reference Okosun, Chandra and Boev 28 ).

The quantification of visceral obesity is best determined by imaging examinations (such as computed tomography or dual-energy X-ay absorptiometry). The problem is that radiological measurements may not always be feasible in most clinical contexts, where anthropometric indicators are usually recommended( Reference Zamboni, Mazzali and Zoico 6 , Reference Roriz, Passos and de Oliveira 29 ). Some recent studies have estimated adiposity using the waist circumference (WC) measure, which has been recommended as a better measurement for nutritional screening because it is easy to measure and strongly related to visceral and total fat( Reference Harris, Visser and Everhart 30 – Reference Visscher, Seidell and Molarius 32 ). WC is much more cost-effective and can be easily used at all health-care levels, especially in primary care, where resources may be scarce. In developing countries, like Brazil, it is important to count on cheap screening which can be effective in properly identifying people with higher risk.

Based on that, our hypothesis is that abdominal obesity can be a more informative measure and a risk marker independently from general obesity. Thus, the aim of the present study was to assess the role of abdominal obesity, measured by WC, in the incidence of disability in older adults living in São Paulo, Brazil, in a 5-year period.

Methods

Sample and procedures

The data came from the SABE Study (Health, Wellbeing and Aging), which is a longitudinal study that began in 2000 and involved a multiple-stage probabilistic sample of individuals (aged 60 years or above) who live in São Paulo (n 2143). Individuals aged 75 years or above were oversampled to compensate for the higher mortality rate in this age group. Sample weights took this oversample into consideration to represent the population. A second wave was carried out in 2006 and a third wave was conducted in 2010. In each new wave, a new sample of older adults between 60 and 64 years old was added following similar procedures used in the first wave. Details on the methodology of the study are described elsewhere( Reference Andrade, Guevara and Lebrao 33 , Reference Pires Corona, Drumond Andrade and de Oliveira Duarte 34 ).

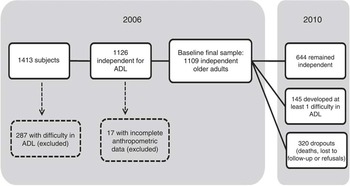

For the current analysis we used the second wave, carried out in 2006, as baseline (n 1413). We selected 1126 participants who were independent in activities of daily living (ADL). In 2010, 800 of them were located and re-interviewed. From the 1126 older adults selected at the baseline, seventeen did not have anthropometric measurements and were excluded. Thus, our final sample had 1109 independent older adults in 2006. Figure 1 describes the final sample.

Fig. 1 Status of the SABE Study (Health, Wellbeing and Aging) sample, from 2006 baseline to the end of follow-up in 2010 (ADL, activities of daily living)

Measurements

The 2006 and 2010 data included a household face-to-face interview conducted by a single interviewer using a standardized questionnaire addressing the living conditions and health status of the older adult respondent. Anthropometric measurements and physical tests were collected by a trained interviewer in another household visit.

The incident disability was the dependent variable and was recorded when the participant reported difficulty in one or more ADL in 2010 for which no difficulty was reported in 2006. The activities of daily living analysed were: walking across a room, dressing, bathing, feeding, transferring and toileting. Despite its importance among older adults, incontinence was not included because it does not necessarily imply physical limitation( Reference Guralnik and Simonsick 35 ).

Body weight was measured using a calibrated scale, and height was measured using stadiometer fixed to a wall, with the barefoot individual wearing light clothing. BMI (kg/m2) was calculated by dividing body mass (in kilograms) by the square of height (in metres). Nutritional status was classified based on BMI cut-off points adopted by the Pan American Health Organization for the SABE Study( 36 ): ≤23·0kg/m2=underweight; >23·0 and <28·0kg/m2=normal range (reference); ≥28·0 and <30·0 kg/m2=overweight; ≥30·0 kg/m2=obesity. We adopted these cut-off points to keep the same pattern of previous SABE publications and because they are really close to those proposed by Lipschitz( Reference Lipschitz 23 ) (i.e. the most used for older adults). Since obesity was less common than overweight and could compromise the statistical analysis due to the lower number of participants, we combined the two last categories, considering as overweight/obesity those with BMI values ≥28·0 kg/m2.

Abdominal circumference was measured using an inelastic measure tape by a trained interviewer, at the midpoint between the last rib and the iliac crest, with the abdomen relaxed at the end of expiration, with the individual without shirt in an upright position with arms relaxed at body sides. Participants were classified with abdominal obesity when WC ≥102 cm in men and ≥88 cm in women, according to the cut-offs proposed by the National Cholesterol Education Program’s Adult Treatment Panel III( 37 ).

Sociodemographic and health-related variables measured at baseline were also included in the analysis. Baseline health status was assessed based on self-reported diabetes, hypertension, cancer, CVD, osteoarticular conditions, chronic respiratory disease and stroke.

Grip strength was measured using a dynamometer (Takei Kiki Kogyio® TK 1201), with two measurements, selecting the highest one between them. We classified low grip strength in men as values under 26 kg and in women as values under 16 kg( Reference Studenski, Peters and Alley 38 ).

Physical activity was self-reported using the Brazilian version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire( Reference Guedes, Lopes and Guedes 39 ). We classified as physically inactive (sedentary) those who reported less than 150 min of moderate activities per week or less than 75 min of vigorous activities per week( 40 ).

Cognitive status was evaluated using a modified version of the Mini Mental State Exam validated for the SABE Study, due to the low level of schooling of the South American older adult population. This measurement has thirteen items that are less dependent upon schooling, with a total possible score of 19 points. Those with a score of 12 or lower were classified as having cognitive impairment( Reference Icaza and Albala 41 ).

Statistical analysis

For the descriptive analysis, mean values and their standard errors were calculated for continuous variables, and proportions were calculated for categorical variables. Differences between groups were estimated using the Wald test of mean equality and Rao–Scott correction, which considers sample weights for estimates with population weights.

The crude density of the incidence of disability in the 5-year period was calculated considering the participants who did not have disability at baseline. For the calculation of incidence density, the numerator was made up of the number of individuals who developed difficulty in one or more ADL in the period and the observation times were summed in the denominator. In cases of death, the observation time was the interval between the 2006 interview and the date of death. For deaths with unknown date, the observation time was the interval between the 2006 interview and a date attributed to the death based on the mean date of death of known cases in the same age group and gender. For those who did not develop disabilities, the observation time was the period between the 2006 interview and 2010 interview. For those who developed disabilities, the observation time was half the period between the 2006 and 2010 interviews. Refusals to participate, cases of institutionalization and non-located individuals also counted for half the period between the 2006 and 2010 interviews, once it was not possible to determine the date. The incidence density was also calculated according to BMI categories and for each ADL separately, according to abdominal obesity.

Poisson multiple regression analysis was performed to evaluate the association between abdominal obesity and disability incidence in the period, incorporating those covariables with a P value <0·20 in the univariate regression. Variables were maintained in the final model if statistically significant (P<0·05) or if they adjusted the estimates by at least 10 %. All analyses included sample weights and were adjusted for the complex sampling design. Data analyses were performed using the statistical software package Stata® version 12.

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants at baseline, according to their follow-up status. Among the 1109 independent participants at baseline, mean age was 69·2 years, schooling average was 4·5 years, mean BMI was 26·6 kg/m2 and mean WC was 90·8 cm. After the 5-year period, 146 participants died and 174 refused to participate or were lost in the period. Most of the dropouts were men, older, had lower BMI and grip strength values, lower prevalence of abdominal obesity and higher prevalence of cognitive impairment. Education, physical inactivity and self-reported chronic conditions did not differ.

Table 1 Characteristics at baseline and after the follow-up period, according to outcome, among the sample of older adults (≥60 years old) in São Paulo, Brazil. SABE Study (Health, Wellbeing and Aging), 2006 and 2010

Rao–Scott and Wald tests were used to assess differences.

*P value for comparison between dependent and independent in 2010.

Among the 789 older adults interviewed in 2010, 644 remained independent and 145 developed at least one difficulty in ADL. Participants with incident disability were older, less educated and had higher prevalence of chronic conditions at baseline, except for stroke, cardiovascular and pulmonary disease, which were not significantly associated with disability incidence. Nutritional and physical statuses at baseline were also different between groups: those who had incident disability had higher BMI and WC, lower hand grip strength, and higher proportions of obesity and abdominal obesity.

The crude incidence rate of ADL disability (at least one ADL) for all participants was 27·1 per 1000 person-years in the period. The incidence rate was two times higher for those with abdominal obesity in 2006 compared with those without it (39·1 and 19·4/1000 person-years, respectively; P<0·001). This pattern was observed in all BMI levels (Table 2), including normal and underweight older adults.

Table 2 Incidence rate of disability in activities of daily living per 1000 person-years in older adults (≥60 years old) in São Paulo, Brazil, according to the presence of abdominal obesity and BMI categories. SABE Study (Health, Wellbeing and Aging), 2006–2010

Table 2 also presents the incidence rate of each ADL. The activities with higher incidence were dressing, toileting and bathing, while feeding was less incident. Older adults with abdominal obesity had higher incidence in all activities, particularly in dressing and toileting, in which the rate was more than double relative to those without abdominal obesity (P<0·001).

Table 3 displays the results of Poisson regression models for the incidence of disability. In the crude models, general obesity and abdominal obesity were both predictive of disability. When both variables were in the same model, controlled for the other significant factors presented in the descriptive analysis, abdominal obesity was still significant, presenting a risk 1·90 higher than for those without abdominal obesity (P<0·03), and general overweight/obesity represented by BMI was no longer significant.

Table 3 Results of Poisson regression models for disability incidence in older adults (≥60 years old) in São Paulo, Brazil. SABE Study (Health, Wellbeing and Aging), 2006–2010

IRR, incidence rate ratio.

* Adjusted for age, female gender, years of schooling, low grip strength, physical inactivity, self-reported chronic conditions (hypertension, diabetes, cancer, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis) and cognitive impairment.

Discussion

Our results showed that abdominal obesity is a risk factor for disability in older adults, independent from obesity. An association between obesity and disability is already well documented in the literature( Reference Zamboni, Mazzali and Zoico 6 – Reference Lang, Llewellyn and Alexander 8 , Reference Imai, Gregg and Chen 14 , Reference Galanos, Pieper and Cornoni-Huntley 42 – Reference Gadalla 44 ). In Brazil, our group had already shown that obesity was associated with higher incidence of instrumental ADL disability in a 6-year period( Reference Corona, Pereira de Brito and Nunes 4 ), as well as ADL limitations and lower recovery from Nagi’s limitations( Reference Drumond Andrade, Mohd Nazan and Lebrão 45 ).

A meta-analysis conducted by Carmienke et al.( Reference Carmienke, Freitag and Pischon 46 ) reported that when both BMI and WC measurements were included in the same model, BMI showed either a negative significant or an insignificant association with all-cause mortality, whereas WC showed a significant positive association with mortality when controlled for BMI. The authors recommended that abdominal obesity measurements should be used in clinical practice, in addition to BMI, to assess obesity-related mortality in adults.

Nevertheless, there are few longitudinal studies with community-living older adults, and some of them have conflicting results. A prospective study in Spain showed that the higher quintile of WC was associated with higher incidence of mobility difficulties, but not with ADL disability( Reference Guallar-Castillón, Sagardui-Villamor and Banegas 47 ). Visser et al.( Reference Visser, Harris and Langlois 48 ) did not find a significant association between WC and disability in older participants from the Framingham Study (but the data were not shown in the paper). However, Chen and Guo( Reference Chen and Guo 49 ) analysed the NHANES population in the USA and found that both BMI and WC were predictive for disability in several degrees; but when in the same model, WC attenuated most of the BMI effects. Chen et al.( Reference Chen, Bermúdez and Tucker 50 ) had already shown the same effect in Hispanic older adults: when BMI and WC were included in the same model, WC, but not BMI, remained significantly associated with disability. Na et al.( Reference Na, Park and Kang 51 ) also found that BMI was not related to disability in Korean older adults and abdominal obesity increased the odds of ADL limitation by 2·7-fold.

Studies analysing abdominal obesity and disability are rare in developing countries. In Brazil, so far studies are cross-sectional and have small samples. Nevertheless, they already showed some associations. Campanha-Versiani et al.( Reference Campanha-Versiani, Silveira and Pimenta 52 ) conducted a cross-sectional study with forty-eight women and showed that abdominal obesity was associated with lower scores in functional tests. Another cross-sectional study with seventy-seven older adults showed that abdominal circumference was higher in frail individuals( Reference Bastos-Barbosa, Ferriolli and Coelho 53 ). The only study with a larger sample was a FIBRA (Frailty in Brazilian Elderly) cross-sectional multicentre study that showed that a higher WC was associated with frailty in all BMI categories( Reference Moretto, Alves and Neri 54 ).

Among the possible mechanisms to explain our findings, the most cited in the literature is that obesity can represent a ‘burden’ for the osteomuscular system and can also increase postural instability, which can lead to higher risk of falls (particularly in abdominally obese individuals)( Reference Corbeil, Simoneau and Rancourt 55 ) and limit activities( Reference Vincent, Vincent and Lamb 12 , Reference Guallar-Castillón, Sagardui-Villamor and Banegas 47 , Reference Houston, Stevens and Cai 56 , Reference Rossi-Izquierdo, Santos-Pérez and Faraldo-García 57 ). Several authors also point out that, due to the fact that abdominal obesity is highly associated with diseases that lead to disability (such as diabetes, cardiovascular conditions, cancer, etc.), this association could be confounded( Reference Guallar-Castillón, Sagardui-Villamor and Banegas 47 , Reference Na, Park and Kang 51 , Reference Houston, Stevens and Cai 56 , Reference Houston, Nicklas and Zizza 58 ); however, our results are consistent even after controlling most of those conditions, including osteoarthritis.

This higher burden that obesity could cause to the osteomuscular system may not be clear enough if only body weight is analysed; many studies have concluded that obesity was associated with higher bone mineral density and could actually prevent fractures( Reference Villareal, Apovian and Kushner 15 – Reference Felson, Zhang and Hannan 17 ). But more recently the literature has been demonstrating that obesity induces chronic inflammation, which may reduce muscle mass and increase bone absorption( Reference Mankowski, Anton and Aubertin-Leheudre 27 , Reference Na, Park and Kang 51 , Reference Cesari, Kritchevsky and Baumgartner 59 ), and thus obesity could even increase risk of ankle and upper leg fractures( Reference Compston, Watts and Chapurlat 60 ). Inflammation is already known as an important risk factor for disability, mainly mediated by its role in sarcopenia and lower physical function( Reference Cesari, Kritchevsky and Baumgartner 59 , Reference Ferrucci, Harris and Guralnik 61 – Reference Cesari, Penninx and Pahor 63 ). In this sense, it is plausible that abdominal obesity may have a role in disability modulated by inflammation, independently of chronic diseases.

Another point that should be considered is that weight loss has been widely described as a risk factor for mortality. Several studies have already shown that weight change (weight loss or weight gain) is more harmful than maintaining weight during the ageing process( Reference Waters, Ward and Villareal 64 – Reference Nilsson, Nilsson and Hedblad 67 ). So maybe general obesity should not be targeted with severe weight-loss programmes, but abdominal obesity should be targeted to reduce risk, instead of body weight per se.

It is important to notice that, when analysing each ADL, the incidence for dressing and toileting were higher. In a study analysing SABE’s first follow-up period (2000 to 2006), the most incident ADL were dressing and transferring for men and women; toileting had an incidence of 4·3/1000 persons per year for men and 10·9/1000 persons per year for women( Reference Alexandre, Corona and Nunes 68 ). Jagger et al.( Reference Jagger, Arthur and Spiers 69 ), on the other hand, found that women had higher risk of disability in bathing and toileting relative to men, but the order of activity restriction was bathing, mobility, toileting, dressing, transfers from bed and chair, and feeding. They suggested that lower-extremity disability (bathing, mobility, toileting) precedes upper-extremity disability (feeding), with difficulty for dressing being either upper-extremity or lower-extremity disability( Reference Jagger, Arthur and Spiers 69 ). Dunlop et al.( Reference Dunlop, Hughes and Manheim 70 ), on the contrary, argued that dressing may require only upper-extremity flexibility/dexterity, in addition to cognitive functioning. In our point of view, dressing requires upper-limb strength, fine motor coordination, flexibility, lower-limb strength and balance( Reference Alexandre, Corona and Nunes 68 ), and these conditions can be strongly affected by abdominal obesity( Reference Moretto, Alves and Neri 54 , Reference Delmonico, Harris and Visser 71 , Reference Carneiro, Santos-Pontelli and Vilaça 72 ).

In our study, the incidence was more than two times higher in abdominally obese older adults for the activities of both dressing and toileting. Guallar-Castillón et al.( Reference Guallar-Castillón, Sagardui-Villamor and Banegas 47 ) also found that the highest quintile of WC was associated with bathing or dressing difficulties in women, but not in men. So, it is plausible to understand that dressing could be affected by a ‘physical barrier’ such as a higher WC to cope with all those skills. The same explanation can be hypothesized for toileting in our study: the physical barrier can impact skills that can be necessary to perform this activity without help, such as flexibility, strength and mobility, and balance.

Our results should be interpreted taking some points into consideration. Disability was measured using self-reported information; nevertheless, methodological studies have demonstrated that self-reported data on functional disability have adequate validity and are consistent with medical diagnoses and/or physical tests( Reference Reuben, Siu and Kimpau 73 ). Another limitation is the high proportion of losses, which may influence our results.

The study also has some strong points. First, it was conducted in a large representative sample of community-living older adults in the biggest city in Brazil. Second, it is a prospective cohort that analysed only independent older adults at baseline, so it shows a possible role of abdominal obesity in the disability pathway. To our knowledge, the present study is the first one in Brazil with a large representative sample and with longitudinal follow-up.

Conclusion

Our study shows that abdominal obesity is a risk factor for disability in older adults, independently from BMI, and we consider that WC is a simple, cost-effective and easily interpreted measurement, and therefore can be used in several settings, from hospitals to primary care facilities, to identify individuals with higher risk of disability. Thus, abdominal obesity should be a target for intervention to avoid or postpone disability, cardiovascular events and mortality.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This work was supported by São Paulo Research Foundation (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, FAPESP) (grant number 2009/53778-3). FAPESP had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: L.P.C. was responsible for study design and formulated the research question. Y.A.O.D. and M.L.L. were responsible for data collection and are Principal Investigators of the main study. The statistical analyses, results and discussion were performed by L.P.C. and T.S.A. All authors participated in the drafting of the manuscript and approved its final version. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the University of São Paulo. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients.