The Intestinal Failure Service at St. Mark's Hospital acts as a national referral centre for complex intestinal failure (IF) patients, some of whom require Home Parenteral Nutrition (HPN; including home parenteral nutrition, home intravenous fluid and/or electrolyte support). Funding for the homecare element of the HPN must be provided by the patient's Primary Care Trust (PCT; or Health Board in Ireland) by seeking price quotations from the minimum two specialist homecare companies (HCC; companies A and B) for provision of HPN and forwarding to the PCT with a letter requesting written authorization.

Prospective data for a 1-year period to June 2007 was collected on referrals to the St. Mark's IF service for consideration of HPN. A period of initial assessment maximizing oral/enteral feeding determined those who may require HPN.

Eighty-three referrals were initially assessed as possibly requiring HPN. Three patients (3.6%) died as in-patients, twenty eight (33.7%) were discharged with other therapies including subcutaneous fluids with electrolytes (six patients), gastrostomy (three patient), jejunostomy (one patient) or nasogastric (four patients) feeding or oral diet (fourteen patients) alone. One patient had restorative surgery and one patient is continuing with assessment.

Fifty patients (thirty-one female, 19 male, mean age 53 years (range 22–77 years)) were discharged on HPN. The forty-five patients were referred from thirty-three different PCT (mean 1.4 patients per PCT, range 1–3, median 1). Median distance by road from home to St. Mark's for forty-two of the forty-five patients (two lived in Ireland, one in the Isle of Wight) was 49 miles (range 2.7–398 miles).

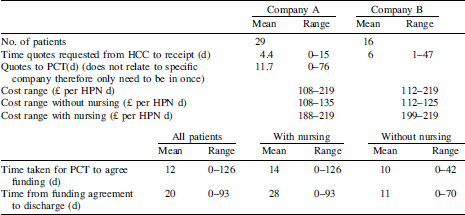

Forty-five of the fifty patients had funding for their HPN arranged by St. Mark's Hospital (one PCT arranged HPN via local hospital with aseptic unit); the other four patients had their funding arranged by other Trusts (two in Ireland, one in England, one in Scotland). Funding for Specialist Nursing to support procedures at home was requested for twenty-two (48%) patients and agreed by the PCT for twenty. Time and costs involved in this process are outlined in the Table.

At one year, forty-two patients continue with their HPN, four have stopped HPN (one by another hospital, three after restorative surgery) and four died post-discharge.

Sixty percent of patients referred for assessment for HPN were discharged with HPN. For those undergoing HPN therapy, the funding process is prolonged. While there may be small differences between the two HCC used, these do not affect length of stay. The greatest influence on length of stay is the patient's clinical condition and recovery, particularly if specialist nursing is required at home. These data may be important for centres planning to develop services for HPN.