The worldwide prevalence of individuals defined as overweight and obese has risen by over 25 % since 1980(Reference Ng, Fleming and Robinson1). Whilst the development of overweight and obesity likely involves a combination of genetic, environmental and psycho-social factors, in its simplest form it can be attributed to an imbalance between energy intake (i.e. diet) and energy expenditure (i.e. physical and metabolic activity)(Reference Wright and Aronne2). Diet is a modifiable risk factor for overweight and obesity, and due to the strong associations between total body fatness and risk of metabolic diseases such as type-2 diabetes (T2DM) and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), the increase in the number of individuals defined as overweight and obese represents a major global health challenge(Reference Grundy3). Here we review evidence regarding the influence of dietary fats on liver fat content.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an overview

NAFLD, which has been termed the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome, encompasses a spectrum of liver disease ranging from steatosis to hepatocellular carcinoma, the causes of which are not attributable to alcohol or substance abuse(Reference Dyson, Anstee and McPherson4). NAFLD is currently recognised as the most prevalent form of liver disease worldwide, estimated to affect about 25 % of the global population(Reference Younossi, Anstee and Marietti5), although due to the limited availability of valid and reliable, non-invasive diagnostic tests, it has been suggested that the true figure may be even greater(Reference Araujo, Rosso and Bedogni6). Hepatic steatosis (which is often referred to as NAFLD, and is the first stage in the NAFLD spectrum) is the net retention of intracellular TAG, and is defined histologically as the presence of intracellular TAG in >5 % of hepatocytes, or when the proton density fat fraction is >5·6 % when measured by MRI/spectroscopy(7).

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease risk factors

A number of modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors have been identified for NAFLD. Non-modifiable risk factors include (1) sex, with Caucasian males being more susceptible to NAFLD than Caucasian females(Reference Browning, Szczepaniak and Dobbins8,Reference Schneider, Lazo and Selvin9) ; (2) ethnicity, Asian and Hispanic populations have a greater prevalence of NAFLD compared with Caucasian and Black populations(Reference Younossi, Anstee and Marietti5,Reference Schneider, Lazo and Selvin9,Reference Pan and Fallon10) and (3) carrying specific genetic variants of patatin-like phospholipase domain containing protein three, or transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2 amongst others(Reference Anstee and Day11).

The major modifiable risk factors include: (1) increased body fatness(Reference Fabbrini, Sullivan and Klein12); (2) a sedentary lifestyle or low physical activity levels(Reference Hallsworth, Thoma and Moore13) and (3) dietary intake(Reference Parry and Hodson14). However, it is challenging to define the contribution that specific dietary components may play in the aetiology of NAFLD from those of total macronutrient intake, as total body fatness (which is typically a product of excess energy consumption) is strongly associated with increased liver fat(Reference Angulo15). This inability to disentangle the effects of total energy (TE) and macronutrient intakes likely explains, in part, the observation that both high-fat diets enriched in SFA, and high-carbohydrate diets enriched with free sugars are both associated with increased liver fat(Reference Volynets, Kuper and Strahl16,Reference Cheng, Zhang and Chen17) . In addition to total macronutrient intakes a further area of interest relates to how consumption of SFA, MUFA and PUFA may differentially affect liver fat content independently of energy intake. However, at this point in time, only a few studies have been undertaken comparing the influence of isoenergetic diets with different fat compositions on liver fat content in vivo in human subjects, making it challenging to draw robust conclusions. Thus, the precise role of specific dietary fats in liver fat content, and the mechanisms through which they have their effects, is yet to be fully clarified. In this review we summarise the available evidence from human studies regarding dietary fat consumption (and where available composition) and the effect on liver fat content, and highlight areas for potential future investigation.

Overview of hepatic dietary fatty acid metabolism

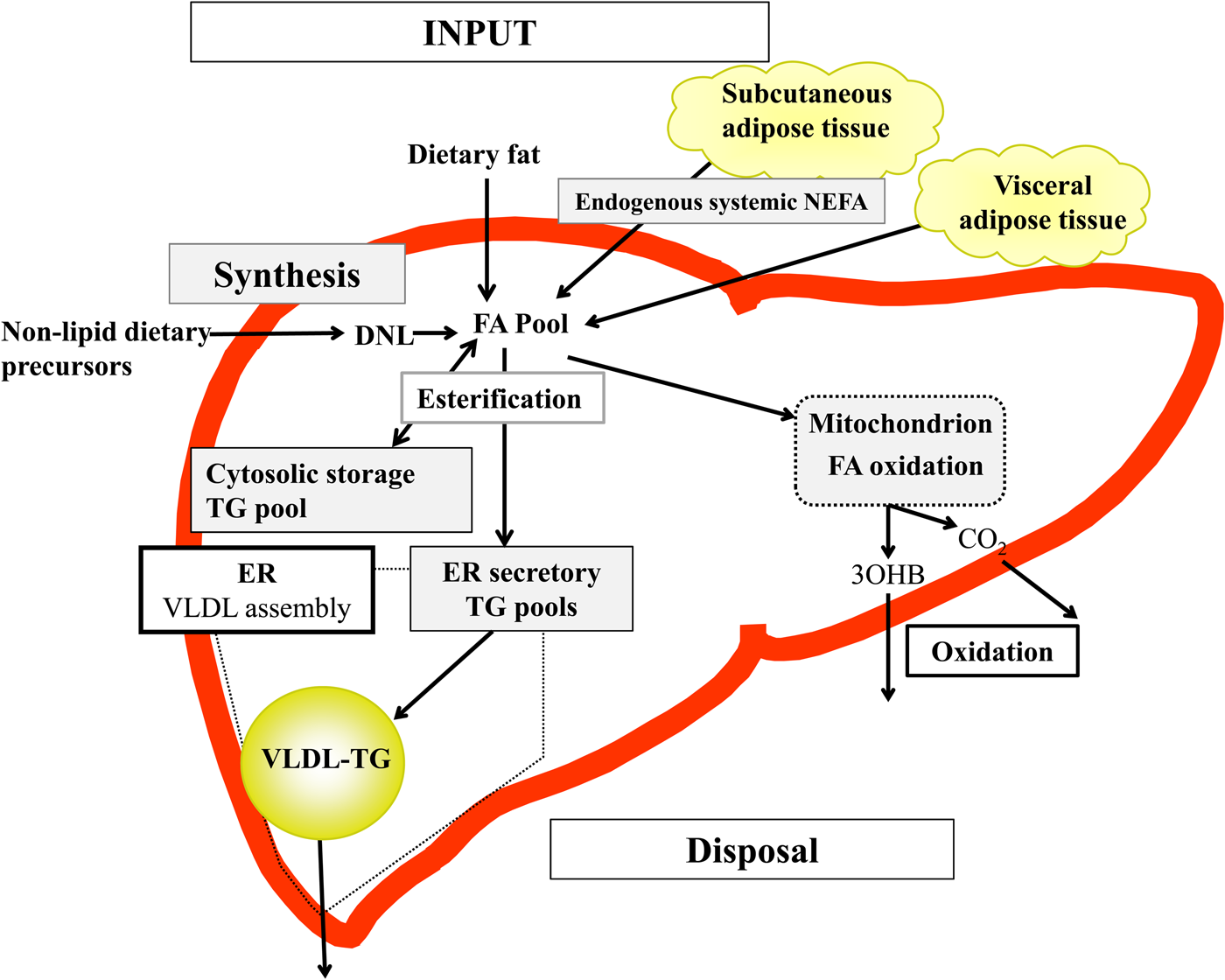

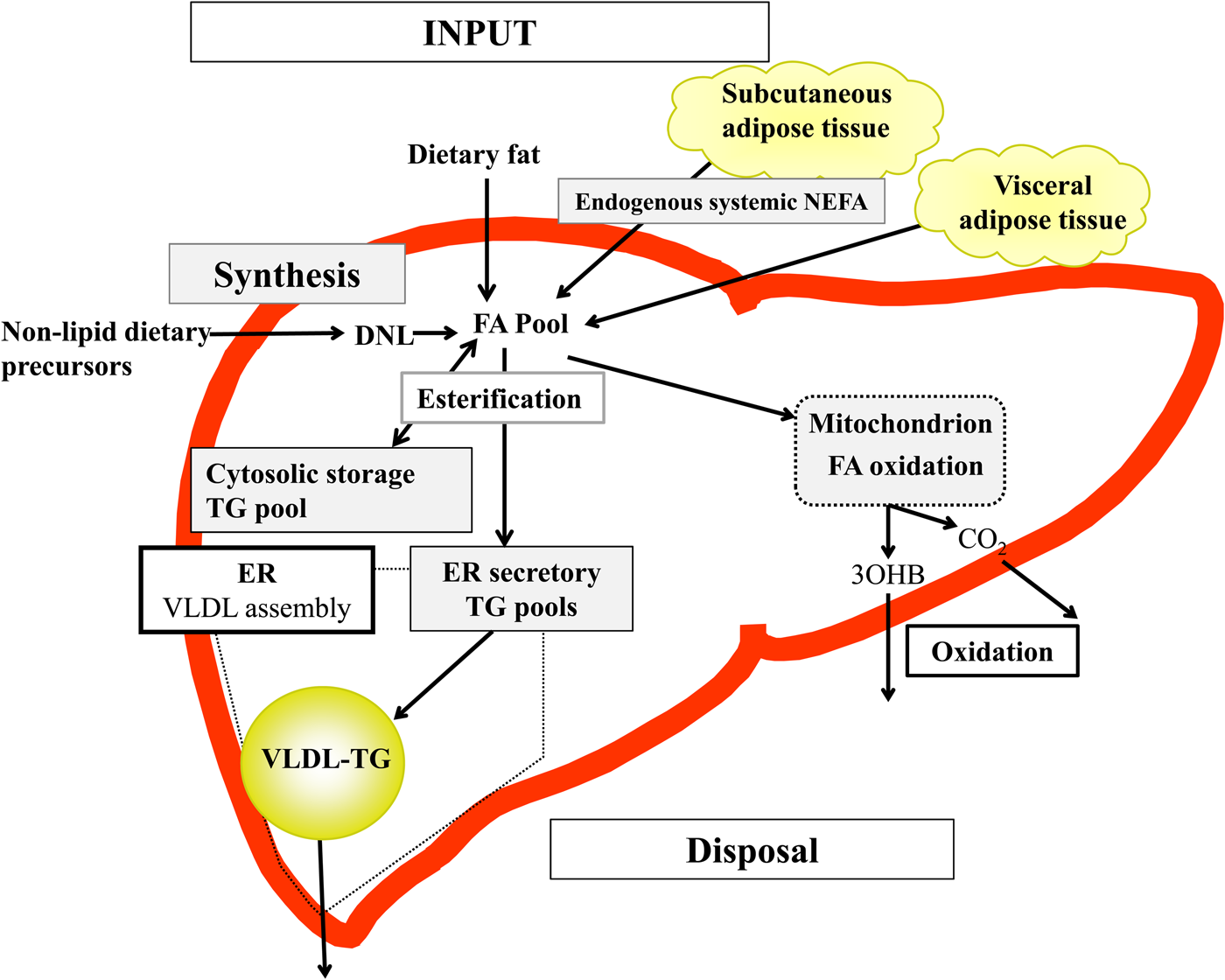

The accumulation of fat within the liver represents an imbalance between the amount of fatty acids entering the liver (input), fatty acid synthesis within the liver and fatty acid disposal from the liver (output)(Reference Hodson and Frayn18). Investigation of these pathways will provide an understanding of the effect of diet and dietary components on the pathogenesis, and potentially progression, of NAFLD; we have recently reviewed methodologies for investigating hepatic fatty acid metabolism in human subjects(Reference Green, Parry and Gunn19).

Briefly, in the fasted state the input of fatty acids to the liver are derived predominantly from adipose tissue lipolysis (known as systemic NEFA)(Reference Donnelly, Smith and Schwarzenberg20–Reference Hodson, McQuaid and Humphreys23), and in the postprandial period dietary fatty acids enter, as chylomicron-derived spillover fatty acids(Reference Hodson, Bickerton and McQuaid22,Reference Miles, Park and Walewicz24,Reference Piche, Parry and Karpe25) and chylomicron remnants(Reference Hodson, Bickerton and McQuaid22,Reference Heath, Karpe and Milne26) (Fig. 1). Fatty acids synthesised within the liver from non-lipid precursors (e.g. dietary sugars), via the process of de novo lipogenesis (DNL)(Reference Hellerstein, Schwarz and Neese27,Reference Diraison, Moulin and Beylot28) also contribute to the intrahepatic fatty acid pool (Fig. 1). Within the liver, fatty acids are broadly partitioned into either esterification pathways to form predominantly TAG which may then be incorporated into VLDL and secreted into systemic circulation or stored in the cytosolic TAG (as lipid droplets) or, an alternative fat for intrahepatic fatty acids is that they may be partitioned into oxidation pathways (either the tricarboxylic acid/Krebs cycle or ketogenesis)(Reference Hodson and Frayn18).

Fig. 1. (Colour online) Overview of hepatic fatty acid (FA) input, synthesis and disposal in the postprandial state. FA input to the liver derives from (1) the lipolysis of adipose (subcutaneous and visceral) tissue TAG (TG), and (2) dietary fat, which enter the liver as either chylomicron remnants or chylomicron-derived spillover FA. FA synthesis occurs within the liver, via de novo lipogenesis (DNL) which involves the synthesis of FA from acetyl-CoA derived from non-lipid precursors, such as glucose. These FA enter a common pool and can then be broadly partitioning between two pathways for disposal. One is the esterification pathway, where predominantly TG is produced which can then be either stored in the cytosol (as a lipid droplet) or can lipidate VLDL in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to form VLDL-TG and then secreted into the systemic circulation. The other possible fate for FA disposal is oxidation either via the tricarboxylic acid cycle to form CO2, or the ketogenic pathway where β-hydroxybutyrate (3OHB) is produced and enters the systemic circulation.

To elucidate the contribution of dietary fatty acids to intrahepatic TAG (IHTAG) content ideally, the contribution of dietary fatty acids to liver TAG would be measured directly. To date, only one study has assessed the contribution of different fatty acid sources to IHTAG in subjects with NAFLD. By using stable-isotope tracer methodology, they found after 5 d labelling that the relative contribution of systemic NEFA, DNL fatty acids and dietary fatty acids to IHTAG was 59, 26 and 15 %, respectively(Reference Donnelly, Smith and Schwarzenberg20). The authors reported that the contribution from the respective fatty acid sources was similar in VLDL-TAG(Reference Donnelly, Smith and Schwarzenberg20), suggesting that VLDL-TAG could be used as a proxy marker of IHTAG. Further support for the notion that VLDL-TAG may be a proxy for IHTAG comes from Peter et al.(Reference Peter, Cegan and Wagner29) who, when comparing the fatty acid composition of liver tissue with various blood lipid fractions, found that the 16:1/16:0 ratio in IHTAG strongly correlated with the 16:1/16:0 ratio in VLDL-TAG. Studies that have used stable-isotope methodology and measured the contribution of different fatty acid sources to VLDL-TAG have found that 75–84 % of fatty acids are derived from the circulating NEFA pool, whereas DNL fatty acids are estimated to contribute 10–22 %; although both these pathways may be influenced by obesity and insulin resistance(Reference Hodson30). The data for the contribution of dietary fatty acids are somewhat variable, ranging between 12 and 39 %(Reference Donnelly, Smith and Schwarzenberg20–Reference Hodson, McQuaid and Humphreys23,Reference Vedala, Wang and Neese31) , as this will be influenced by meal composition (i.e. the amount of fat consumed), size of the meal and timing of when samples are collected after the meal(s). Studies utilising 13C/31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy have reported that IHTAG content is rapidly increased (within 360 min) in response to a single high-fat load in healthy lean individuals, and remains elevated for up to 5 h(Reference Lindeboom, Nabuurs and Hesselink32,Reference Hernandez, Kahl and Seelig33) . Ravikumar et al.(Reference Ravikumar, Carey and Snaar34) reported a significantly higher increment in IHTAG content in individuals with T2DM after consumption of a mixed test meal, compared with lean controls; baseline IHTAG content was also significantly higher in T2DM compared with controls. Thus, it is plausible that consumption of high-fat foods at regular intervals over the course of a day long-term, would lead to an increased delivery of dietary fatty acids to the liver that exceeds the livers disposal capacity, leading to an accumulation of IHTAG.

The limited availability of liver tissue also makes it challenging to investigate intrahepatic fatty acid composition. It has been reported that when compared with age and BMI matched non-NAFLD controls, NAFLD patients have lower levels of intrahepatic PUFA(Reference Kotronen, Seppanen-Laakso and Westerbacka35), although it is unclear whether this is attributable to differences in specific lipid fractions. By analysing the fatty acid composition of erythrocytes and liver phospholipids from individuals with and without NAFLD, Elizondo et al.(Reference Elizondo, Araya and Rodrigo36) demonstrated that liver phospholipids from obese patients with NAFLD had a lower abundance of 20:4n-6, 22:5n-3 and 22:6n-3 when compared with controls. They also found that levels of DHA within the liver were positively correlated with those in erythrocytes(Reference Elizondo, Araya and Rodrigo36), suggesting that erythrocyte fatty acid composition could be a useful indicator of liver phospholipid fatty acid composition in obese, NAFLD patients. Petit et al.(Reference Petit, Guiu and Duvillard37) measured erythrocyte fatty acid composition in T2DM patients with and without NAFLD, and found higher proportions of total SFA, and lower proportions of PUFA in erythrocytes in those who had NAFLD (n 109) compared with those without (n 53).

Measuring the fatty acid composition of blood lipid fractions is an objective and useful marker of dietary fatty acid intake(Reference Hodson, Skeaff and Fielding38). To date a limited number of studies have measured plasma fatty acid composition and liver fat content and investigated associations. For example, Rosqvist et al.(Reference Rosqvist, Bjermo and Kullberg39) observed that the abundance of linoleate in plasma phospholipids and cholesterol esters were inversely associated with IHTAG content in a population-based sample of seventy-eight elderly men and women. Although observational, these data suggest that individuals that have a higher abundance of plasma lineolate, presumably due to a higher dietary intake, have a lower IHTAG than individuals with a lower intake.

Dietary fatty acids and liver fat

The findings from cross-sectional/observational studies investigating the associations between dietary fat intake and IHTAG content are variable and inconsistent in demonstrating whether the total amount and the type of fat consumed is associated with IHTAG content(Reference Cheng, Zhang and Chen17,Reference Musso, Gambino and De Michieli40–Reference Baratta, Pastori and Polimeni44) . The variability and discrepancies in results between studies is likely to be in part explained by how and when liver fat content was assessed, in combination of how dietary intake was assessed and over what time period. To fully understand the impact (and potentially causal nature) of dietary fat on IHTAG accumulation evidence from intervention studies provides some insight.

Dietary fatty acids and liver fat content: evidence from intervention studies

Total fat

Whether the proportions of dietary carbohydrate and fat play a key role in IHTAG accumulation is highly debated. During isoenergetic conditions, in interventions lasting ≤4 weeks diets higher in carbohydrate (about 60 % TE carbohydrate, about 20 % TE fat) appear to reduce IHTAG to a greater extent when compared with diets that are higher in fat (about 50 % TE fat, about 30 % TE carbohydrate)(Reference Westerbacka, Lammi and Hakkinen45–Reference Marina, von Frankenberg and Suvag48). In contrast, in interventions lasting 6–12 weeks diets higher in fat (about 45 % TE fat, about 35 % TE carbohydrate) have been reported to decrease IHTAG to a greater extent than diets higher in carbohydrate (about 50 % TE carbohydrate, about 25 % TE fat)(Reference Bozzetto, Prinster and Annuzzi49–Reference Errazuriz, Dube and Slama51). Notably, the higher-fat diets in the latter interventions (6–12 weeks) were primarily enriched in unsaturated fats, in contrast to the shorter term studies where the higher-fat diets were primarily enriched in SFA(Reference Westerbacka, Lammi and Hakkinen45–Reference Marina, von Frankenberg and Suvag48). Furthermore, subjects in the longer-term studies had prediabetes, T2DM and/or NAFLD, whilst subjects in the shorter-term studies were considered metabolically healthy, which may have contributed to the divergence in findings between high- (about 40 to 56 % TE as fat) and low-fat diets (about 16 to 30 % TE as fat). A recent meta-analysis reported that due to the large heterogeneity between studies, there is no difference in IHTAG reductions between low-carbohydrate (about 24 % TE as carbohydrate) and low-fat diets (about 20 % TE as fat)(Reference Ahn, Jun and Lee52).

In a recent short-term (2 weeks) study without a control group, Mardinoglu et al.(Reference Mardinoglu, Wu and Bjornson53) investigated the effects of an extreme low-carbohydrate (4 % TE), high-fat (72 % TE, fat quality not specified) diet in ten subjects with NAFLD (IHTAG content about 12 %) and demonstrated large reductions (>40 %) in IHTAG content. The large decrease in IHTAG is likely to be due to a combination of factors including: (i) modest (2 kg) weight loss, (ii) decreased hepatic DNL, which is likely to be explained by a lack of non-lipid precursors and (iii) increased fatty acid oxidation. Although results are impressive, the longer term effects (including compliance) to such an extreme low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet remains to be determined. Considering the large effect of energy restriction (i.e. weight loss) on IHTAG content, it is unsurprising that dietary composition appears to not be a key mediator of IHTAG content during hypoenergetic conditions(Reference Kirk, Reeds and Finck54,Reference Haufe, Engeli and Kast55) . Although it has been suggested that extreme carbohydrate restriction (8 % TE) may aid in decreasing IHTAG content further than fat restriction, despite hypoenergetic conditions(Reference Browning, Baker and Rogers56), further well-controlled investigations are required to clearly demonstrate this.

In a long term (18-month) randomised trial in 278 subjects (89 % male), Gepner et al.(Reference Gepner, Shelef and Schwarzfuchs57) compared a hypoenergetic low-fat diet with a hypoenergetic Mediterranean diet and found that although overall weight loss (about 3 kg) was not different between diets, the Mediterranean compared with the low-fat diet resulted in a greater loss of IHTAG after statistical adjustment. However, although the macronutrient compositions of the diets are unclear, when calculated, it appears that the dietary intakes of carbohydrate and fat were quite similar between the two interventions (the low-fat diet containing about 45 % TE carbohydrate, and about 34 % TE fat, and the Mediterranean diet about 39 % TE carbohydrate, and about 41 % TE fat) suggesting other dietary factors may underpin the observed reductions in IHTAG content.

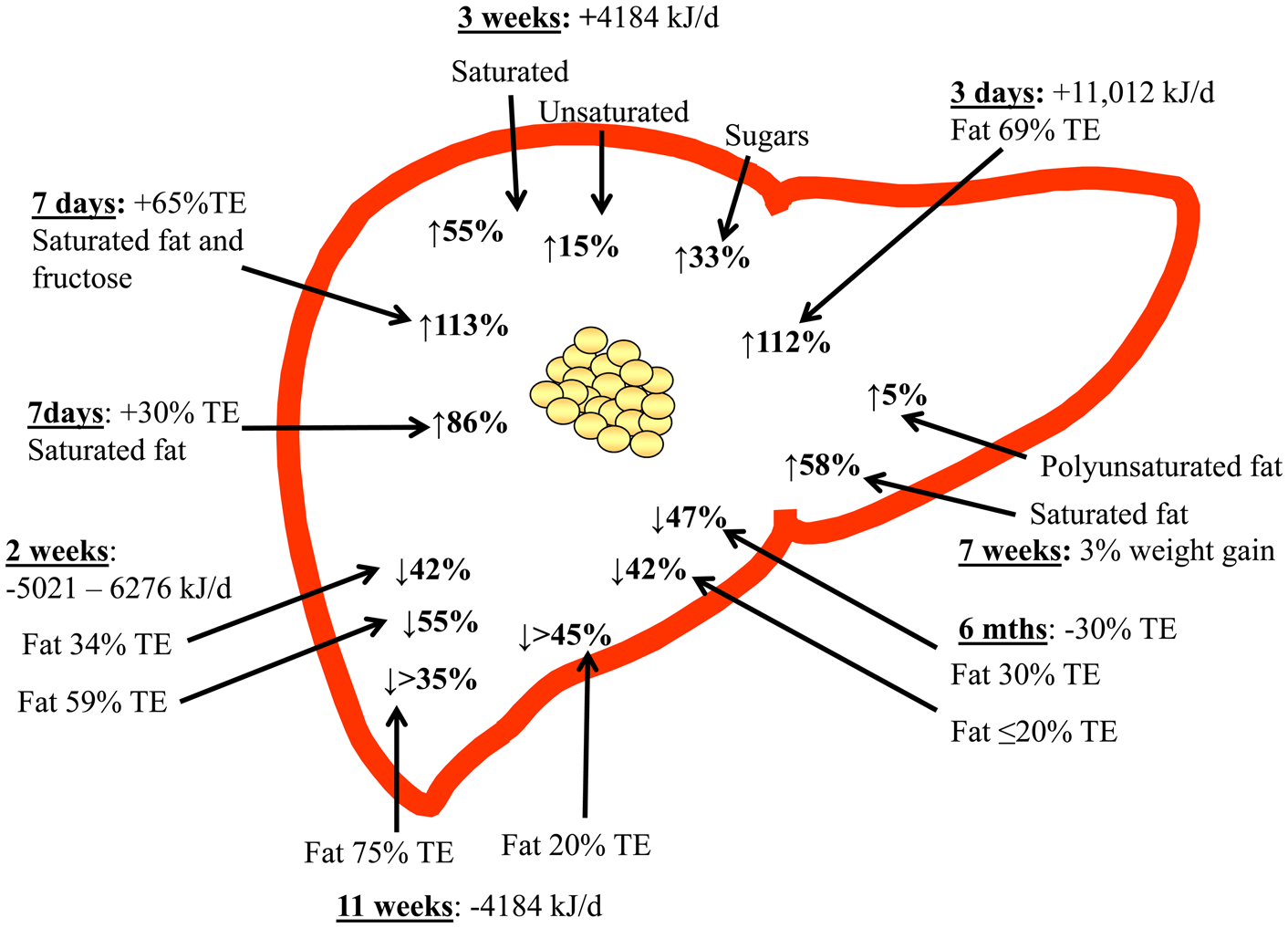

Few studies have compared the proportions of fat and carbohydrate during hyperenergetic conditions(Reference Sobrecases, Le and Bortolotti58,Reference Lecoultre, Egli and Carrel59) . Sobrecases et al. observed a 16 % increase in IHTAG after 7 d fructose overfeeding (+35 % TE) and a 86 % increase after 4 d SFA overfeeding (+30 % TE) in young, lean and healthy men, suggesting SFA increases IHTAG to a greater extent than fructose during hyperenergetic conditions(Reference Sobrecases, Le and Bortolotti58). The combination of fructose and SFA overfeeding for 4 d resulted in a 133 % increase in IHTAG content however as surplus energy intake also increased (+65 % TE) it is unclear how much is due to nutrient synergy compared with energy excess. As weight gain is likely a key driver of increased IHTAG it is difficult to disentangle nutrient-specific effects during concurrent weight gain. In agreement with these findings, Lecoultre et al.(Reference Lecoultre, Egli and Carrel59) reported a greater relative increase (about 90 % increase) in IHTAG after a SFA (30 % energy excess) enriched diet for 6–7 d compared with overfeeding 3·0 g/kg bodyweight glucose (about 60 % increase in IHTAG), although they found no significant difference in IHTAG after feeding 1·5, 3·0, or 4·0 g/kg bodyweight fructose in young, healthy, males. The differences in energy intake and durations of overfeeding between diets within and between studies make it difficult to compare and interpret the findings. For example, the increased IHTAG content after carbohydrate/sugar overfeeding may in part be explained due to increased hepatic DNL, although as this is an energy inefficient method of accumulating IHTAG compared with storing pre-formed fat, it is plausible that the increase in IHTAG is smaller when overfeeding carbohydrate/sugar compared with isoenergetic fat overfeeding(Reference Solinas, Boren and Dulloo60).

SFA

Marina et al.(Reference Marina, von Frankenberg and Suvag48) reported that increasing SFA intake from about 12 % TE to about 24 % TE (total fat from 35 % TE to 55 % TE) over a 4 week period failed to increase IHTAG during isoenergetic conditions in ten healthy subjects with elevated IHTAG (8–9 %), whereas a slight decrease in SFA intake (from about 12 % TE to about 8 % TE) within a low-fat/high-carbohydrate diet (20 % TE fat, 62 % TE carbohydrate) decreased IHTAG in a within-group analysis however, diets were not significantly different in a between-group comparison. In a larger study (n 61), Bjermo et al.(Reference Bjermo, Iggman and Kullberg61) found that an isoenergetic increase in SFA (from about 15 % TE to about 20 % TE) over 10 weeks increased IHTAG compared with a diet enriched in n-6 PUFA in obese, middle-aged subjects. In line with this, Rosqvist et al.(Reference Rosqvist, Iggman and Kullberg62) demonstrated that overfeeding SFA for 7 weeks increased IHTAG to a greater extent compared with similar overfeeding of n-6 PUFA in young and lean subjects. Luukkonen et al.(Reference Luukkonen, Sadevirta and Zhou63) also recently reported a 55 % increase in IHTAG after 3 weeks SFA overfeeding (+4184 kJ/d) compared with a 33 % increase and a 15 % increase in IHTAG after 3 weeks simple sugar or unsaturated fat (mixture of MUFA and PUFA) overfeeding (+4184 kJ/d) in obese, middle-aged men and women. By using stable-isotope tracer methodology, Luukkonen et al.(Reference Luukkonen, Sadevirta and Zhou63) demonstrated that the SFA diet was associated with an increase in adipose tissue lipolysis which would lead to a greater fatty acid flux (adipose tissue and dietary) to the liver, whilst the simple sugar diet was associated with an increase hepatic DNL. Although the unsaturated fat diet was associated with a decrease in lipolysis and no change in DNL, it is likely that the excess energy from the fat resulted in an increased flux of dietary fatty acids to the liver. What remains unclear from these studies is how the specific fatty acids alter intrahepatic fatty acid partitioning.

Overall, it appears that increased consumption of a SFA-enriched diet increases IHTAG, although it remains unclear if different sources of SFA (e.g. dairy v. meat) may potentially have different effects on liver fat content. For example, Kratz et al.(Reference Kratz, Marcovina and Nelson64) observed that circulating biomarkers of dairy fat intake (the fatty acids 15:0, 17:0 and trans-16:1) were inversely associated with liver fat content in seventeen subjects with NAFLD (assessed by computer tomography-derived liver–spleen ratio) and fifteen age and BMI-matched subjects without NAFLD. Although based on a small sample size, this finding is in-line with the general finding of reduced risk of T2DM with higher circulating abundance of dairy fat biomarkers(Reference Imamura, Fretts and Marklund65). Different dairy products have distinctly different effects on cholesterolaemia, even when total intake of SFA from these food items is matched(Reference Hjerpsted, Leedo and Tholstrup66,Reference Rosqvist, Smedman and Lindmark-Mansson67) , highlighting the importance of other food components. A differential effect of various SFA sources on IHTAG has yet to be demonstrated in human subjects but would be a logical and interesting direction for future studies.

MUFA

Bozzetto et al.(Reference Bozzetto, Prinster and Annuzzi49) reported that consumption of an isoenergetic high-MUFA diet (27 % TE) for 8 weeks decreased IHTAG (about 30 % relative reduction) compared with a normal-MUFA diet (16 % TE). Similarly, Errazuriz et al.(Reference Errazuriz, Dube and Slama51) reported IHTAG to decrease during 12 weeks of a high- (22 % TE) compared with a low- (7 % TE) MUFA diet, during isoenergetic conditions. In a randomised cross-over study where the majority of foods were provided, Ryan et al.(Reference Ryan, Itsiopoulos and Thodis50) compared a high-MUFA Mediterranean diet (44 % TE fat, 23 % TE MUFA) with a low-fat diet (21 % TE fat, 8 % TE MUFA) over 6 weeks and found reductions in IHTAG tended to occur to a greater extent after the high- compared with low-MUFA diet. In contrast, Properzi et al.(Reference Properzi, O'Sullivan and Sherriff68) showed similar reductions in IHTAG when a high-MUFA Mediterranean diet (45 % TE fat, 24 % TE MUFA, 37 % TE carbohydrate) was compared with a lower-fat diet (31 % TE fat, 12 % TE MUFA, 48 % TE carbohydrate) consumed ad libitum for 12 weeks. A similar decrease in IHTAG may, in part, be due to the slightly hypoenergetic nature of the diet as there were reductions in body weight of between 1·6 and 2·1 kg; there was no difference in SFA intake between groups. As a Mediterranean diet consists of a relatively high intake of nutrient dense foods such as fruit and vegetables(Reference Drewnowski69), it is challenging to isolate the effects of MUFA as it is plausible that other components of a Mediterranean diet are beneficial for reductions in IHTAG(Reference Anania, Perla and Olivero70); elucidating the influence of specific components on IHTAG, although interesting would be an extremely challenging endeavour. Moreover, this would not be specific to the Mediterranean diet but to all diets/dietary patterns based on minimally processed food items. For example, Otten et al.(Reference Otten, Mellberg and Ryberg71) demonstrated superior reductions in IHTAG by a higher-fat (43 % TE fat, 30 % TE carbohydrate) paleolithic-type diet (based on lean meat, fish, eggs, vegetables, fruit, berries and nuts) compared with a lower-fat (32 % TE fat, 44 % TE carbohydrate) conventional diet. However, as both diets were hypoenergetic and also differed in fat quality it is difficult to disentangle which component(s) may contribute the greatest to the change in IHTAG.

The potential importance of phytochemicals (e.g. β-carotene, vitamin E, folate and flavonoids), which are high in the Mediterranean diet(Reference Anania, Perla and Olivero70), in the prevention and management of NAFLD is gaining interest, with studies in different animal models showing beneficial effects on both steatosis and various biomarkers (e.g. liver enzymes)(Reference Salomone, Godos and Zelber-Sagi72,Reference Basu, Basu and Lyons73) . Studies in human subjects are thus far limited but of those available, results generally show beneficial effects on liver enzymes(Reference Salomone, Godos and Zelber-Sagi72,Reference Basu, Basu and Lyons73) , despite having very reductionist designs unlikely to represent a complex diet. Taken together, the reductions in IHTAG when a plant-based diet rich in minimally processed food items (e.g. the Mediterranean diet) is consumed is likely to be explained by both changes in the classical components such as fat and carbohydrate quality but also by the content of micro- and non-nutrient compounds. More studies in human subjects investigating this concept are needed, given that lifestyle modifications are still the first and most effective line of treatment of NAFLD.

n-6 and n-3 PUFA

The specific effects of dietary n-3 and n-6 PUFA intakes are of interest due to their potential influence on metabolic health(Reference Forouhi, Imamura and Sharp74,Reference Calder75) .

n-3 fatty acids

The two most recognised n-3 PUFA are EPA and DHA, which are predominantly found in fatty fish and fish oils. Another n-3 PUFA, α-linolenic acid is present in certain seed- and plant-based foods (e.g. flaxseed oil, walnuts, soyabeans and soyabean oil, pumpkin seeds, rapeseed oil and olive oil(Reference Gebauer, Psota and Harris76)). Mammalian cells have the capacity to further metabolise α-linolenic acid to EPA and DHA through elongation and desaturation pathways(Reference Calder75).

Animal models have suggested that increasing n-3 PUFA intakes leads to a reduction in IHTAG(Reference Pachikian, Neyrinck and Cani77,Reference Marsman, Heger and Kloek78) and evidence from observational studies suggests that when compared NAFLD with non-NAFLD patients consume less n-3 PUFA(Reference Zelber-Sagi, Nitzan-Kaluski and Goldsmith79). Evidence from human intervention studies demonstrates that, when compared with placebo, supplementation with n-3 PUFA decreased IHTAG across a spectrum of phenotypes, including patients with T2DM(Reference Dasarathy, Dasarathy and Khiyami80), NAFLD(Reference Capanni, Calella and Biagini81–Reference Scorletti, Bhatia and McCormick84) and polycystic ovarian syndrome(Reference Cussons, Watts and Mori85), with the response appearing to occur independent of changes in body weight; although not all studies have observed a reduction in IHTAG with n-3 PUFA supplementation(Reference Oscarsson, Onnerhag and Riserus86). Moreover there is some suggestion that n-3 PUFA supplementation may ameliorate the clinical symptoms of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis(Reference Tanaka, Sano and Horiuchi87,Reference Li, Yang and Sha88) , although this is not observed by all(Reference Sanyal, Abdelmalek and Suzuki89).

The majority of studies investigating the effect of n-3 PUFA on IHTAG have been supplementation studies with EPA and/or DHA in combination or alone with concentrations ranging from 250 mg up to 4 g/d; the upper intake exceeds both the WHO recommendations for EPA/DHA intakes (250–2000 mg/d(Reference Sioen, van Lieshout and Eilander90)), and the estimated intakes of all n-3 PUFA for UK adults (about 2·2 g/d(Reference Pot, Prynne and Roberts91)), although the recommended clinical dose for lowering TAG levels is 2–4 g/d of EPA and DHA(Reference McKenney and Sica92). To put this in context, a typical portion of salmon contains about 500 mg EPA and 1·3 g DHA per 100 g consumed(Reference Calder75), thus supplementation, rather than diet, is the only plausible way to achieve the intakes reported to lower IHTAG. As the duration of the studies investigating n-3 PUFA supplementation and IHTAG ranges from 8 weeks to 24 months, in combination with the wide range of n-3 PUFA doses used, it is challenging to determine what (if any) optimal n-3 PUFA intakes could be for reducing IHTAG and whether they could be achieved by diet alone. Furthermore, it is unclear if the ratio between EPA and DHA is a significant mediator of IHTAG, as studies comparing EPA v. DHA are yet to be undertaken.

To date, the majority of the focus has been on EPA and DHA and their effects on IHTAG, with relatively little attention being given to α-linolenic acid. Of the limited work undertaken, Nogueira et al.(Reference Nogueira, Oliveira and Ferreira Alves93) investigated differences in histopathological features in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis patients before and after supplementation with 945 mg/d of a α-linolenic acid, EPA and DHA mix (about 64, 16 and 21 % of total fatty acids, respectively) for 6 months. The authors reported that n-3 PUFA supplementation did not influence hepatocellular ballooning, steatosis or fibrosis when compared with a mineral oil control(Reference Nogueira, Oliveira and Ferreira Alves93), although a substantial confounder to the study results was the fact that plasma n-3 PUFA levels also increased in the control group, suggesting an increased n-3 PUFA intake (by fish or supplements)(Reference Nogueira, Oliveira and Ferreira Alves93) making it difficult to draw conclusions. By comparing the whole cohort, the authors observed a significant positive correlation between the rate of increase in plasma α-linolenic acid and EPA levels and improvements in steatosis, lobular inflammation and ballooning, suggesting a beneficial role for n-3 supplementation in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis patients(Reference Nogueira, Oliveira and Ferreira Alves93).

n-6 fatty acids

Whilst the evidence would suggest that n-3 PUFA intake, specifically EPA and DHA, may play a role in modulating liver fat content, n-6 PUFA consumption is notably higher than n-3 PUFA consumption in a typical Western style diet, with the majority of dietary PUFA being from linoleic acid. Despite linoleic acid being the major PUFA consumed, only a few studies have investigated the effects of this fatty acid on IHTAG. Bjermo et al.(Reference Bjermo, Iggman and Kullberg61) demonstrated that a high intake of n-6 PUFA (10–15 % TE from linoleic acid) in abdominally-obese men and women for 10 weeks reduced IHTAG compared with a higher intakes of SFA, in the context of an isoenergetic diet. In a double-blind follow-up study, Rosqvist et al.(Reference Rosqvist, Iggman and Kullberg62) observed that a similarly high intake of n-6 PUFA (10–15 % TE) during hyperenergetic conditions for 7 weeks did not lead to accumulation of IHTAG, which was in contrast to the group consuming SFA. As the subjects in the study by Rosqvist et al.(Reference Rosqvist, Iggman and Kullberg62) were healthy, young, lean adults, with very low levels of IHTAG, it would be of interest to undertake a similar study in other populations. To date, no study has directly compared the effects of n-3 and n-6 PUFA on IHTAG, which would be interesting, although challenging to do due to the imbalanced dietary intake of n-3 v. n-6 PUFA.

Potential mechanisms of fatty acids: specific effects on liver fat metabolism

Although it appears that different fatty acids may have differential effects on IHTAG accumulation, the mechanistic basis remains to be elucidated, although a number of proposed mechanisms have been suggested, work is required to provide a clear demonstration.

There have been a number of mechanisms proposed for the effect of SFA on IHTAG accumulation and these include: increased inflammation in adipose tissue leading to increased lipolysis(Reference Luukkonen, Sadevirta and Zhou63), thereby increasing the fatty acid flux to the liver, and increased ceramides(Reference Luukkonen, Sadevirta and Zhou63); the fatty acid 16:0 is a precursor for ceramide synthesis and ceramides have been suggested to cause insulin resistance (which may lead to IHTAG accumulation). The latter hypothesis is supported by animal work which has demonstrated a role for ceramides in IHTAG accumulation(Reference Raichur, Wang and Chan94,Reference Xia, Holland and Kusminski95) . Moreover, evidence from animal and cellular studies has suggested that increased intracellular accumulation of SFA caused cell dysfunction and up-regulate pro-inflammatory pathways(Reference Field, Ryan and Thomson96–Reference Leamy, Egnatchik and Shiota98) which may, eventually lead to IHTAG accumulation.

There is a commonly held, but largely unsubstantiated view that dietary PUFA are more prone to enter oxidation pathways compared with both MUFA and SFA, and hence the latter (SFA) are more likely to be to be stored promoting IHTAG accumulation. Although, human evidence is limited, this view is generally supported by animal work. From the available evidence in human subjects, Jones et al.(Reference Jones, Pencharz and Clandinin99) fed, in random order, meals labelled with either 13C-labelled stearic, oleic and linoleic acid to six young (mean age 27·3 years) and lean (mean BMI 20·9 kg/m2) males and analysed the recovery of 13C in breath CO2 as a measure of whole-body dietary fatty acid oxidation. They found significantly greater recovery of 13C from oleate, compared with 13C from linoleate in breath (15·1 % v. 10·2 % cumulative recovery after 9 h, respectively), and this occurred to a greater extent than the appearance of 13C from stearate (2·9 % cumulative recovery after 9 h)(Reference Jones, Pencharz and Clandinin99). In a cross-over study, Schmidt et al.(Reference Schmidt, Allred and Kien100) fed 13C-labelled oleate and palmitate in frequent (every 20 min) small meals over 7 h to ten young (mean age 24·7 years) and lean (mean BMI 22·9 kg/m2) men and women and found a 21 % (95% CI 10,32 %) higher oxidation of oleate compared with palmitate. Finally, DeLany et al.(Reference DeLany, Windhauser and Champagne101) fed 13C-labelled laurate, palmitate, stearate, oleate, elaidate, linoleate and linolenate in random order as part of a single meal to four normal-weight men. It was found that oxidation of SFA decreased with increasing carbon number and oxidation of C18 fatty acids was positively correlated with the number of double-bonds; the overall order of oxidation was laurate > linolenate > elaidate > oleate > linoleate > palmitate > stearate(Reference DeLany, Windhauser and Champagne101). However, palmitate, stearate, oleate and linoleate were not statistically different from each other, with cumulative recoveries of 13C in breath CO2 ranging between 11 and 17 % 9 h after the meal(Reference DeLany, Windhauser and Champagne101). On the basis of the limited, available evidence it appears that there may be differential oxidation of unsaturated and SFA however it would be important to determine if these responses diverge between males and females, as we have previously reported sexual dimorphism in dietary fatty acid oxidation(Reference Pramfalk, Pavlides and Banerjee102). Regardless, if different fatty acids are differentially oxidised or not, some (unsaturated) fatty acids may potentially stimulate general fat oxidation by activating transcription factors such as PPARα(Reference Forman, Chen and Evans103). Whether this translates to meaningful effects in vivo in human subjects has, to our knowledge, not yet been demonstrated and evidence would in fact suggest a contrasting response as, somewhat counterintuitively, a synthetic PPARα agonist was recently observed to increase IHTAG content in subjects with NAFLD(Reference Oscarsson, Onnerhag and Riserus86).

The results from studies using indirect calorimetry to assess fasting and postprandial energy expenditure and fat oxidation are conflicting and challenging to interpret. For instance there are reports of increased postprandial fat oxidation after meals enriched in unsaturated fatty acids when compared with meals enriched in SFA(Reference Piers, Walker and Stoney104–Reference Yajima, Iwayama and Ogata106), and there is some evidence to suggest that consuming diets enriched in oleic acid results in a greater postprandial fat oxidation compared with diets enriched in SFA. However, not all studies are in agreement with these findings, as they have found no difference in postprandial fat oxidation following meals that are high in SFA or unsaturated fatty acids(Reference Jones and Schoeller107–Reference Clevenger, Stevenson and Cooper110), or following diets enriched in fatty acids of different saturation status(Reference Piers, Walker and Stoney111,Reference Gillingham, Robinson and Jones112) . Indeed, it was found that consuming a diet enriched in MUFA for 28 d, resulted in a reduced postprandial fat oxidation compared with diets enriched in SFA or trans-fatty acids(Reference Lovejoy, Smith and Champagne113). Plausible explanations for the discrepancies in findings between studies include differences in study design (e.g. single meal crossover v. interventions lasting several weeks), study populations (e.g. sex and BMI) and different methodology used (e.g. metabolic chamber v. ventilated hood) and the total macronutrient composition and content of test meals given to participants.

With regards to the effects of n-3 PUFA on IHTAG, work from animal and cellular models have demonstrated that EPA and DHA affect the metabolic nuclear receptors, liver X receptor, hepatocyte nuclear factor-4α , farnesol X receptor and PPAR; all of which play a role in modulating plasma TAG concentrations(Reference Davidson114) and presumably IHTAG content. Therefore, a proposed model for the effects of n-3 PUFA (EPA and DHA) on IHTAG accumulation is at the level of gene transcription by co-ordinately suppressing hepatic lipogenesis through sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factor 1c inhibition and up-regulating hepatic fatty acid oxidation through PPAR activation(Reference Davidson114). Taken together the coordination of these effects would have the net result of an intrahepatic effect of repartitioning fatty acids away from esterification and towards oxidation pathways. In support of this, in a pilot study we observed that in individuals who achieved a change in erythrocyte DHA enrichment ≥2 %, after 15–18 months supplementation with EPA + DHA (4 g/d) there was a significant reduction in fasting hepatic DNL, along with a more notable (although non-significant) decrease in IHTAG content compared with individuals who had a <2 % change in DHA abundance (placebo group)(Reference Hodson, Bhatia and Scorletti115). As this was only a pilot study, further work is required to confirm these observations.

The findings that n-6 PUFA could decrease IHTAG and/or prevent IHTAG accumulation (compared with SFA) is generally supported by animal studies, but the primary mechanism remains unclear. Animal studies have suggested differential effects on hepatic DNL but this is not supported by findings in human subjects. Konrad et al. fed isoenergetic diets high or low in palmitate and linoleate for 21 d to healthy males and females and found no difference in isotopically assessed hepatic DNL(Reference Konrad, Cook and Goh116). Similarly, Luukkonen et al. found no difference in isotopically assessed hepatic DNL after overweight/obese adults consumed hyperenergetic diets rich in SFA or unsaturated fats for 3 weeks(Reference Luukkonen, Sadevirta and Zhou63) despite IHTAG increasing to a notably greater extent on the SFA diet. Together these data imply that hepatic DNL is not the primary mechanism behind the differential effects of SFA and n-6 PUFA on IHTAG content in human subjects.

In addition to oxidation and storage pathways, palmitate derived from both hepatic DNL and dietary sources may be further metabolised within the liver, e.g. desaturated by stearoyl-CoA desaturase to generate palmitoleate and/or elongated to generate stearate, vaccinate and oleate. Whether partitioning through these pathways is an important mediator for IHTAG accumulation in response to dietary SFA (or PUFA) and although animal studies suggest a potential role for stearoyl-CoA desaturase(Reference Hodson and Fielding117), this has not been investigated in human subjects. The overall intracellular partitioning of DNL-derived lipids is likely to be of importance and may, in part, explain inter-individual outcomes in response to fatty acid overload(Reference Lodhi, Wei and Semenkovich118). It could be speculated that linoleate may modify IHTAG accumulation by affecting the efficiency of partitioning through these pathways as linoleate is known to repress stearoyl-CoA desaturase(Reference Hodson and Fielding117). More studies are needed on the potential role of fatty acid desaturation and elongation and the effects on IHTAG in response to different diets. However, disentangling what is causally-related compared with what is an adaptive mechanism to reduce further harm, or responses that just parallel phenomena is challenging to decipher in human studies.

Conclusion

Taking all the available evidence to date, clearly demonstrated that TE intake is a key mediator of IHTAG accumulation, with hyperenergetic diets increasing, and hypoenergetic diet decreasing IHTAG content, irrespective of dietary composition (Fig. 2). In addition to this, there is now emerging evidence to suggest that dietary fatty acid composition may also play a role in regulating of IHTAG, with diets enriched in SFA being associated with greater IHTAG accumulation than diets enriched in unsaturated fatty acids; further work is needed to understand the mechanistic basis for this divergence in the effect on IHTAG accumulation. Supplementation with n-3 PUFA (EPA and DHA) appears to decrease IHTAG, although more studies are required to clearly demonstrate this and whether the same effect can be achieved through dietary intake (rather than supplements) alone, remains to be elucidated. Finally, more work is required to determine the mechanisms by which specific fatty acids elucidate their effects on IHTAG content, and although challenging, taking time to develop in vitro models that better replicate the physiological conditions (i.e. mixture of fatty acids and sugars) and the human subjects of disease of interest (i.e. NAFLD) would aid in bridging this knowledge gap.

Fig. 2. (Colour online) Overview of dietary hyper- and hypo-energy dietary intervention studies and the observed relative change in intrahepatic TAG content. The time of the intervention, along with the energetic (or body weight) increase or decrease is shown, along with the type of fat (where known) that was increased. TE, total energy.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank their colleagues and peers for useful and informative discussions whilst putting this review together.

Financial Support

L. H. is a British Heart Foundation Senior Research Fellow in Basic Science. F. R. is supported by Henning and Johan Throne-Holsts Foundation, Swedish Society for Medical Research, Swedish Society of Medicine and The Foundation Blanceflor.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Authorship

The authors had joint responsibility for all aspects of preparation of this paper.