Introduction

The advent of the new General Medical Services (GMS) contract in 2004, whereby a proportion of general practitioners’ (GPs’) pay became linked to a set of performance indicators, represented a ‘major experiment’ in United Kingdom health policy (Roland, Reference Roland2004).

General practices currently receive four forms of funding. These comprise: a global sum based upon the number of registered patients; a correction factor which tops up funding to guarantee a minimum income; performance-related funding; and funding for providing enhanced services based upon national or local agreements (The Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2010). Performance-related funding is based upon the quality and outcomes framework (QOF) and through which practices can each earn up to 1000 points (each worth around £128) for achieving targets across a range of clinical and organisational indicators; this can account for up to 40% of a practice’s funding. The average income before tax for self-employed GPs who hold contracts with primary care trusts was £106 072 over 2007–2008. Income can vary considerably within the United Kingdom, with the average being around £20 000 lower in Scotland. Income can also vary considerably between GPs on different contracts; for salaried GPs, employed by a practice or a primary care trust and who account for a growing proportion of the workforce, the average income was £55 790 over the same period.

In an era of growing scrutiny into the pay and probity of public servants, (Anonymous, 2009) GPs’ and their leaders should be aware of how their pay and conditions are represented by the media, especially given reports of ‘moral outrage over doctors’ pay’ (Mannion and Davies, Reference Mannion and Davies2008) and the possibility that it may start to influence patient opinions and trust in the profession. We analysed trends in newspaper reporting of GPs’ salaries to examine whether reporting had become more or less favourable since the introduction of the new GMS contract.

Methods

We analysed a sample of articles published online by five UK national daily newspapers between January 2001 and December 2008. We had set out to sample newspapers representing a range of reader demographics and selected The Daily Mail, The Daily Mirror, The Daily Telegraph, The Guardian, The Sun and The Times (National Readership Survey, 2009; Ipsos Mori, 2001). However, we later had to exclude The Daily Mirror as its website could not accommodate our search strategy. Although predominantly ‘right-leaning’ and generally read by older, middle class people, these five newspapers accounted for 69% of all national daily newspapers read over 2007–2008 (National Readership Survey, 2009). We searched online newspaper archives to identify article texts discussing GPs’ salaries using search terms ‘doctor pay’ and ‘GP pay’. Article relevance was further assessed by checking detailed content. We randomly sampled the included articles to achieve a quota of five articles per newspaper per year over 2001–2008.

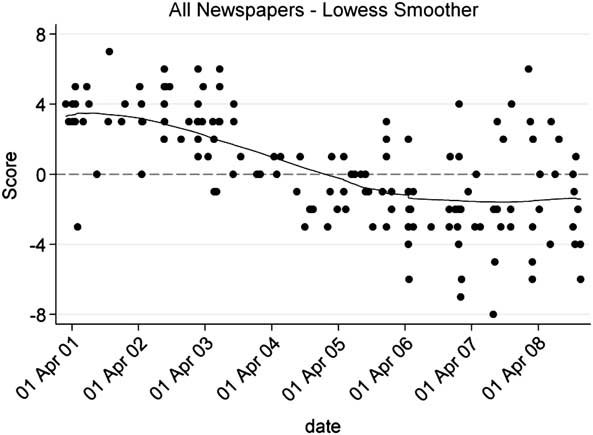

Two authors (F.T. and R.F.) independently reviewed 10% of the sampled articles so that any positive or negative mentions of GPs were assigned scores of +1 and −1, respectively. One author (F.T.) then applied a refined scoring system to the whole sample. Different arguments made within paragraphs generated separate points. We recognised that longer articles would tend to generate more points. We attempted to account for any bias caused by this. Therefore, the same line of argument raised in multiple paragraphs received a point for every third consecutive paragraph where it was mentioned. A new point was allocated if a previously discussed argument was revisited following discussion of a different argument. The number of points was summed for each article. We plotted date of publication against summary score for each article and used locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOWESS) to analyse trends in reporting (Cleveland and Devlin, Reference Cleveland and Devlin1988). We also analysed whether articles written by doctors resulted in more positive coverage. We used an independent samples t-test to compare the mean overall scores between articles written by doctors and those written by non-medically qualified journalists.

We used a grounded approach to identify and code themes that emerged from the articles (Pope et al., Reference Pope, Ziebland and Mays2000). Two authors (F.T. and R.F.) independently assigned and agreed initial codes based on the 10% sample. We jointly refined the coding as the analysis progressed and reapplied revised codes to all articles to increase consistency. One author (F.T.) undertook all the coding while regularly referring any ambiguous extracts to R.F. for discussion and resolution. We sought to reduce observation bias by masking newspaper identity and article date during data extraction. We charted annual frequencies of how many times each theme appeared in our sample. Ethics approval was not required.

Findings

We identified a total of 391 articles related to GPs’ salaries over 2001–2008 and a sharp rise in the annual publication rate after 2004 (Figure 1). As some newspapers (particularly The Sun) published fewer than five relevant articles in certain years and we sampled a quota of up to five articles per newspaper per year, a total of 151 articles were available for further analysis. Figure 2 shows that coverage became less favourable over the time period examined, falling from a score of 3.30 at the start of the curve to −1.41 at the end. The mean overall score for the 13 articles written by doctors was 2.5 compared with 0.1 for those written by non-medically qualified journalists, giving a difference in means of 2.4 (95% CI 0.6 to 4.2; P = 0.01).

Figure 1 Trends in the number of articles reporting GPs’ salaries over 2001–2008.

Figure 2 Trends in how favourably newspaper articles reported GPs’ salaries over 2001–2008 (with negative scores depicting negative coverage and positive scores positive coverage).

Four key themes emerged: working conditions; probity; quality of care; whether GPs were paid a fair salary (Box 1). Initially, most of the media coverage focused on GPs’ working conditions, often highlighting how they needed improvement (Figure 3). Following the introduction of the new contract, interest in salary levels escalated, with several articles particularly focusing on high earners. This was accompanied by a rise in questions about the probity of the scheme, including depictions of GPs as ‘lazy’ and claims that GPs were responsible for NHS deficits. There was relatively less interest in quality of care, excepting concerns about poorer out-of-hours access.

Box 1 Examples of positive and negative coverage for themes

Figure 3 Coverage of themes over 2001–2008.

Discussion

Press coverage of GPs’ salaries became unfavourable following the introduction of the new contract. Initial support for reform of general practice, recognising GPs’ demanding working conditions and relatively poor rewards for their public service transformed into concerns about unfairly excessive income and poor use of public money. These concerns were fuelled by sporadic stories of exceptional ‘greedy’ cases. As well as addressing GP morale and recruitment, the new contract aimed to produce tangible improvements in the quality of patient care. However, this latter theme seems to have been marginalised by the press or skewed towards concerns about reduced out-of-hours access to GPs.

There were three main limitations to our study. First, we only sampled five national newspapers and did not assess other media or regional newspapers. We also acknowledge that our sample was predominantly ‘right-leaning’ and may therefore have been more critical of public sector initiatives implemented by a Labour Government. However, our final sample still covered newspapers read by the majority of British people who read daily newspapers. Second, the interpretation of newspaper articles was inevitably subjective. We attempted to reduce the risk of observation bias by standardising data collection and masking date of publication and source. Third, factors other than the new contract, such as changing public expectations or public scandals about the poor quality of care across all health sectors, may have influenced press coverage of GPs. However, we did focus specifically on articles relating to pay.

While the bad press coverage of GPs and pay has been broadly recognised (Mannion and Davies, Reference Mannion and Davies2008) to the best of our knowledge this is the first systematic analysis of trends and content. Public scandals and bad news are traditionally seen as helping newspaper sales and hence the observed negative trends in press coverage are unsurprising. However, the fairness and emphasis of press coverage has previously been questioned (Hargreaves et al., Reference Hargreaves, Lewis and Speers2003). For example, press reports highlighting exceptional high earners of over £250 000 may have contributed towards impressions that these represented the norm. Around 0.5% of GPs earned this in 2006 (The Information Centre, 2007) and the majority of job vacancies advertised during 2008 were for lower earning salaried GP positions (Iacobucci, Reference Iacobucci2009). Press coverage has also largely sidelined one of the major issues that has received more intensive scrutiny in medical peer-reviewed journals, namely the impact upon the quality and equity of primary care (Doran et al., Reference Doran, Fullwood, Kontopantelis and Reeves2008; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Reeves, Kontopantelis, Sibbald and Roland2009).

Overall, public trust in GPs has remained fairly robust to media criticism (Richards and Coulter, Reference Richards and Coulter2007) but cannot be taken for granted, especially in an era of intensified public scrutiny of public servants perceived to be high earners against a backdrop of tightening public spending. Doctors need to be aware of wider consequences of changes to their pay and conditions. Public perceptions of how GPs are paid may damage patient trust if the drive to meet performance targets is perceived as undermining the duty of doctors to provide patient-centred care, an issue meriting further research.

The subgroup of stories we examined that were written by doctors mitigated the unfavourable trend. This highlights the impact of doctors actively engaging with the media and signals a potential channel to broaden media debate to quality and equity as opposed to costs alone.

Acknowledgement

This work was carried out as part of an intercalated BSc in Primary Care. We are grateful to the Course Director, Kristan Toft, for her support.

Funding

None.

Competing interests

R.F. works as a salaried GP.