Introduction

Pregnancy and lactation represent crucial periods that require attention to nutritional requirements for the wellbeing of both mothers and infants. Prioritising the nutritional needs of the mothers is crucial to ensure proper fetal development, mitigate the risk of complications during pregnancy and foster the growth and development of infants during lactation(Reference Marshall, Abrams and Barbour1).

Recognising the fundamental role of nutrition, countries worldwide have established food-based dietary guidelines (FBDG) as a tool to guide individuals in making informed dietary choices. Despite the availability of these guidelines, their promotion lacks consistent implementations and evaluations in many countries(2,Reference Brown, Timotijevic and Barnett3) . Further, little is known about the awareness and implementation of FBDG in the specific context of pregnancy and lactation.

While existing reviews have explored the content of FBDG, they often concentrate on specific regions, such as the Mediterranean or Europe(Reference Montagnese, Santarpia and Iavarone4,Reference Montagnese, Santarpia and Buonifacio5) or specific food categories, such as dairy(Reference Comerford, Miller and Boileau6). Leme’s 2021 study is one of the few reviews that identified varying levels of adherence to different dietary components; however, it did not extend its analysis to the unique dietary needs of pregnant and lactating mothers(Reference Leme, Hou and Fisberg7). Notably, a gap exists in the literature regarding the comparison of dietary guidelines for populations during pregnancy and lactation and the corresponding adherence levels to these guidelines.

Of the existing literature reporting adherence to FBDG, the outcomes in relation to adherence most often reported are cardiometabolic risk factors. A review in 2022, incorporating data from nine randomised controlled trials (RCT), demonstrated improvements in certain risk factors with adherence, including reduced body mass index (BMI), reduced body fat percentage and enhanced lipid profiles. However, specific impacts of adherence on plasma glucose, insulin and insulin sensitivity remain inconclusive(Reference Deli, Pinto and Hall8). There are no reviews examining the outcomes of adherence to FBDG in pregnant and lactating populations.

This review aims to (1) bridge the existing gaps in the literature by offering a comprehensive overview of dietary guidelines tailored for pregnancy and lactation across different countries and (2) explore studies reporting adherence levels to dietary guidelines, identify factors influencing adherence and investigate the outcomes associated with adherence.

Methodology

This review consists of two different approaches: (1) a review of dietary guidelines across various countries using official dietary guideline documents and (2) a review of articles analysing adherence to dietary guidelines by systematic search strategy.

An examination of FBDG across countries was conducted to identify recommendations that specifically target pregnant and lactating women. A list of the FBDG was obtained from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) official website(2). Complete national FBDG documents were obtained by following the links provided by FAO with manual searches on government websites if the documents were unavailable. The description and summary from the FAO website were used when the English version was unavailable. The recommendations relevant to pregnancy and lactation were compiled from all obtained guidelines and categorised into specific topics. This categorisation included recommendations for extra meals/food, specific food(s) to eat, food(s) to limit, water intake, caffeine consumption, supplementation and precaution on other substances.

A scoping review on pregnant and lactating women’s adherence to the dietary guidelines was conducted following the methodological guidelines recommended by the Joanna Briggs Institute(Reference Aromataris and Munn9). The search strategy employed specific terms within the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases via Ovid, incorporating terms such as (1) adhere* or comply or compli*; and (2) (diet* or food*) adj2 (guideline* or recommendation*); and (3) pregnan* or gestation* or breastfeed* or nursing or lactation or lactating. The search was limited to original journal articles published in English, observational study, focusing on human subjects, adults and females, published up to the search date 8 October 2023. Articles were deemed eligible if they were original research articles that specifically addressed populations of pregnant or lactating women and measured adherence to national dietary guidelines(Reference Page, Mckenzie and Bossuyt10). Data extracted in pre-tested form included general adherence level, adherence to specific food groups and recommendations, factors associated with adherence, and outcomes related to adherence in mothers or infants. The systematic presentation of findings aligns with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses checklist for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) and is detailed in Supplementary Table 1 (Reference Page, Mckenzie and Bossuyt10).

Results

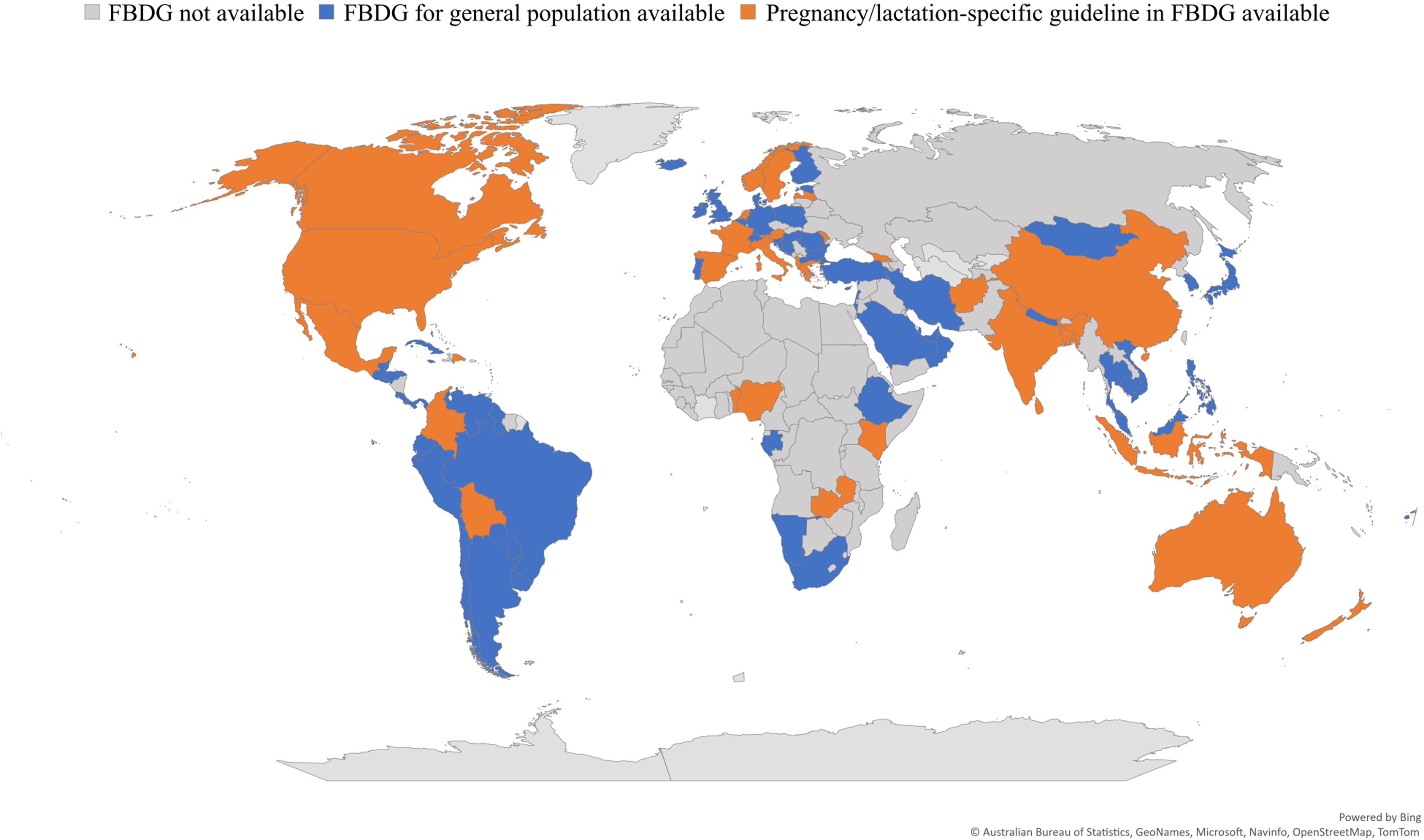

A review of dietary guidelines from 194 countries showed that 98 of them had FBDG. Of these FBDG, thirty included specific guidelines for pregnant and lactating women, with sixteen available in English. An illustrative representation, Fig. 1 (map), visually captures the global distribution of countries with FBDG, including those specifically tailored for pregnant and lactating women.

Figure 1. Countries with food-based dietary guidelines (FBDG) available for the general population and countries with specific guidelines for pregnant and/or lactating women included within their national FBDG.

A systematic search initially identified 281 relevant articles. After a thorough screening process, including the removal of references and duplicates, 199 abstracts were examined. Based on predetermined criteria, 128 studies were excluded. Full-text assessments were then conducted on seventy-one articles to determine their eligibility, resulting in the exclusion of twenty-four studies that did not align with the study’s scope. Finally, forty-seven articles were included in the final review. Details of the screening process are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2. PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the study selection process for the review of dietary guidelines adherence among pregnant and lactating women.

Included articles covering sixteen countries: one low-middle-income country (LMIC), two upper-middle-income countries (UMIC) and thirteen high-income countries (HIC). The LMIC (Sri Lanka) focused on adherence to iron and folic acid supplementation rather than overall recommendations. It is essential to highlight that no comprehensive adherence studies in LMIC or low-income countries (LIC) were identified. Among the forty-seven articles, forty reported adherence during pregnancy, three addressed adherence in both pregnancy and lactation, one specifically explored lactation and three investigated adherence during the periconceptional period.

FBDG for pregnant and lactating women across countries

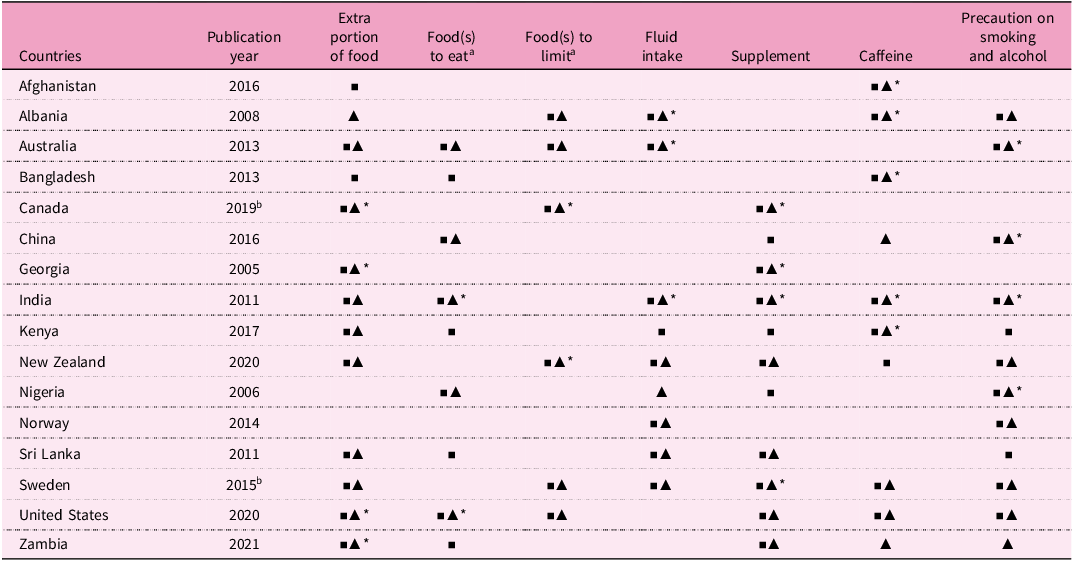

Only half of all countries (51%) have established FBDG. Among countries with FBDG, 81% are from HIC–UMIC, while 19% are from LMIC–LIC. Specifically tailored recommendations for pregnancy and lactation are included in only 31% of all FBDG, with 22% of FBDG from HIC–UMIC and 9% from LMIC–LIC. The publication years of FBDG that incorporate recommendations for pregnancy and lactation range from 2005 to 2021. The number of specific recommendations also varies, ranging from countries like New Zealand, which encompasses a broader spectrum of recommendations, to Georgia, which predominantly focuses on supplementation(11,12) . Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of the advice offered via FBDG to pregnant and lactating women within the national dietary guidelines. It encompasses a diverse range of recommendations, reflecting variations in emphasis and focus across different countries.

Table 1. Overview of recommendation via FBDG for pregnant and lactating women in national dietary guideline

a Other than recommendations for the general population;

b recommendations for pregnancy and lactation is gathered from 2007 version of Canada food guide and 2008 version of Sweden. (▪) pregnancy (P), (▲) lactation (L), (*) recommendation for pregnancy and lactation is the same

Variations in FBDG recommendations

The specific and diverse range of FBDG for pregnant and lactating women from different countries is described in Supplementary Table 2. The following highlights the variations in recommendations.

Food(s) to eat: Adding one to three servings for pregnant and/or lactating women is a typical recommendation across most countries. However, New Zealand and Albania emphasise not needing to ‘eat for two’(11,13) .Countries that provide guidelines on specific food groups during pregnancy and lactation consistently emphasise including animal-source foods. Examples of specific foods mentioned include liver, fish and beef (Nigeria)(14), fish and insects (Zambia)(15), beef, mutton or poultry (Bangladesh)(16), eggs and meat (India)(17), milk, fish and lean meat (China)(18), additional milk (Sri Lanka and Kenya)(19,20) and seafood (United States)(21). Recommendations covering additional consumption of all food groups are found in Australia, Canada, Nigeria, New Zealand, Sri Lanka, the United States and Zambia(11,14,15,19,21–23) .

Food(s) to limit: Most guidelines do not specify particular food items to limit for pregnant and/or lactating women. Sweden recommends avoiding ginseng during pregnancy and lactation declaring it unsuitable for pregnancy. Because high levels of vitamin A can harm the foetus, liver meat is also advised to be limited during pregnancy in Sweden(24,25) . Albania recommends avoiding foods that may alter the taste and flavour of breast milk, such as garlic, onion, cabbage and hazelnuts, as well as foods that may cause potential intolerance, such as fermented cheese, seafood, mussels, cacao, chocolates, strawberries, cherries, peaches and plums(13). In contrast, Australia, New Zealand and the United States do not recommend avoiding foods associated with allergies or intolerances and refer to studies suggesting that avoiding such foods during pregnancy or breastfeeding does not prevent allergies in infants(11,21,22) . However, New Zealand recommends avoiding unpasteurised juices or fermented drinks owing to their potential low alcohol content. Additionally, sugary beverages are discouraged to maintain oral health(11). Precaution to prevent foodborne illness during pregnancy from Listeria monocytogenes, Toxoplasma gondii and some strains of Salmonella during pregnancy was described in Australia, New Zealand, Sweden and the United States to avoid raw meat and eggs, raw or unpasteurised milk and dairy products, and cold food(11,21,22,24) . Precautions related to heavy metal exposure are also mentioned in those countries and Canada to only consume fish low in mercury(11,21–24) .

Fluid intake: In Nigeria, Australia and Albania, increased fluid intake during pregnancy and lactation is recommended without a specific volume stated(13,14,22) . Kenya, India, New Zealand, Sri Lanka, Norway and Sweden also recommend good fluid intake with volumes ranging from eight to twelve glasses daily, including water and other fluids(11,17,19,20,26,27) . Sweden and Norway mention that pregnancy and lactation require additional fluids compared with non-pregnant women, such as 300 ml during pregnancy and 600–1000 ml during lactation(24–26). Nigeria and Sweden suggest that drinking fluids with meals and when thirsty is sufficient to meet daily fluid requirements(14,27) .

Supplementation: There is a diverse range of supplementation strategies recommended. For instance, Kenya, Nigeria and Zambia emphasise recommendations for iron and folic acid(14,15,20) , while Georgia places sole emphasis on iron supplementation.(12) In the United States and China, the focus is primarily on folic acid supplementation(18,21) . New Zealand, on the other hand, recommends both folic acid and iodine supplementation(11).

Caffeine: Zambia, China, India and Albania recommend limiting caffeine intake in pregnancy and lactation without specifying a limit(13,15,17,18) . New Zealand recommends consuming less than 200 mg/d of caffeine during pregnancy(11). Sweden suggests a limit of 300 mg/d of caffeine during pregnancy but does not impose a limitation during lactation, as they stated that the amount of caffeine transferred to breast milk is minimal and does not harm the child(24,25) . The United States recommends consulting healthcare providers to confirm caffeine intake(21).

Precautions on smoking and alcohol: Some countries address the risks of smoking and non-prescribed, addictive or harmful drugs. Most countries also advise caution regarding alcohol consumption during pregnancy. However, some guidelines, such as those from Albania, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden and the United States, allow lactating women a moderate amount of alcohol(11,13,21,25,26) .

Overall adherence of pregnant and lactating women to dietary guidelines

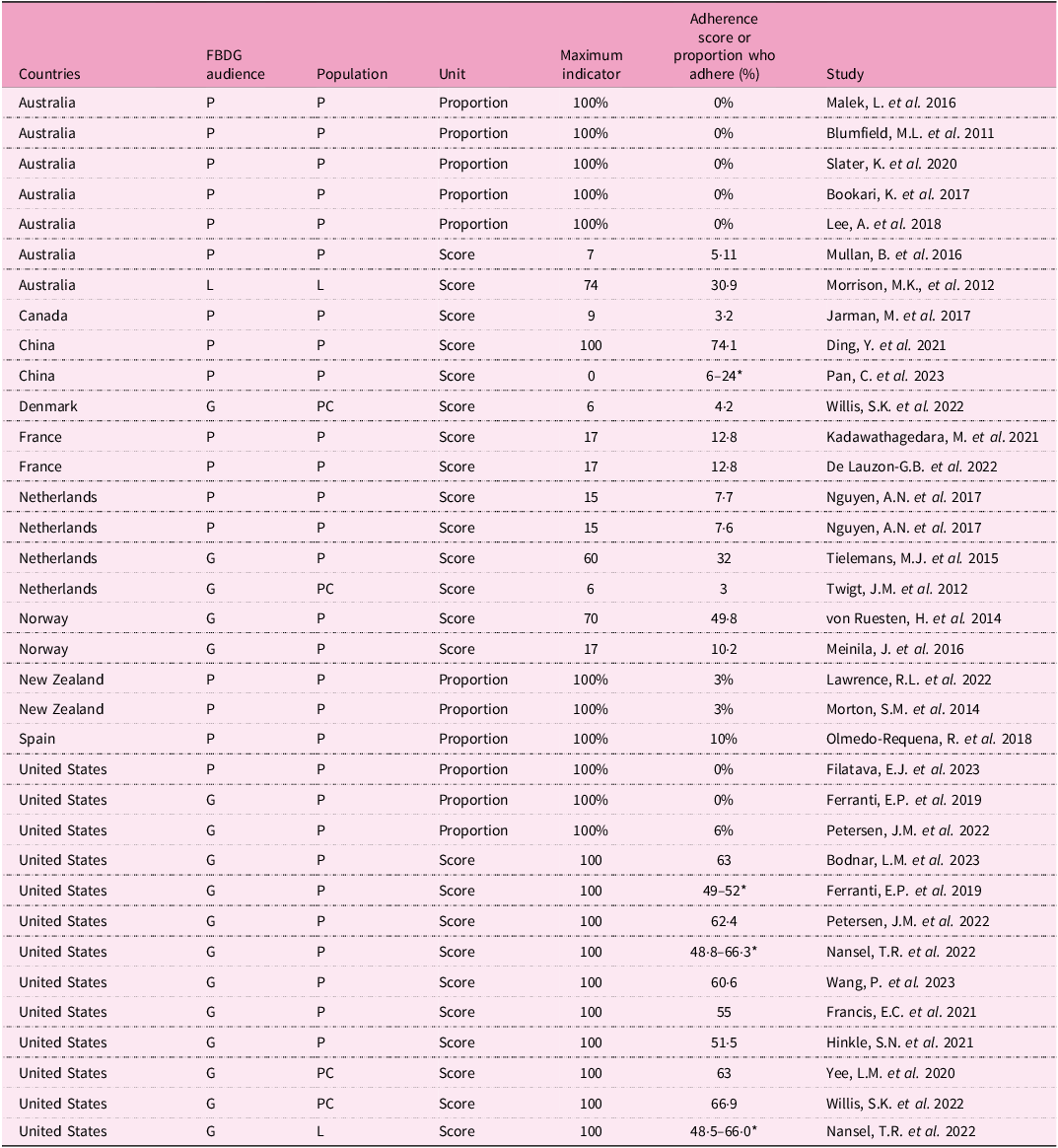

Adherence studies during pregnancy are limited, involving only ten countries with only two reporting adherence studies during lactation (Table 2)(Reference Morrison, Koh and Lowe28,Reference Nansel, Cummings and Burger29) . Nine studies were predominantly from HIC, with one from UMIC (China). There is a notable absence of representation from LMIC or LIC in overall adherence studies for pregnancy and lactation, with a single study in Sri Lanka (LMIC) assessing adherence to iron and folic acid supplementation only(Reference Pathirathna, Wimalasiri and Sekijima30).

Table 2. Overall adherence of pregnant and lactating women across countries

P, pregnancy, L, lactation, PC, preconception, G, general population; *average from different categories (e.g. race/ethnicity). Certain studies solely document adherence at either the overall level or the level of specific food groups.

Some studies do not reference FBDG specifically tailored for pregnancy and lactation; instead, they refer to general population guidelines. Among the studies reporting adherence, the majority indicate very low adherence, ranging from 0% to 10%, to all FBDG.

Several studies were conducted to assess overall adherence scores, focusing on eighteen studies related to pregnancy, two on lactation and four on periconception. Pregnancy adherence was examined in seven countries. In the United States, a standardised measurement was implemented using the Healthy Eating Index (HEI), with scores ranging from 51 to 63 out of a maximum of 100(Reference Nansel, Cummings and Burger29,Reference Ferranti, Hartman and Elliott31–Reference Hinkle, Zhang and Grantz36) . Low adherence was observed in a Canadian study, with one-third of the maximum score(Reference Jarman, Bell and Nerenberg37). In the Netherlands, two studies reported comparable adherence scores at the mid-point of the maximum score(Reference Nguyen, Elbert and Pasmans38,Reference Tielemans, Erler and Leermakers39) . Higher adherence, approximately three-quarters of the maximum score, was reported in Australia (5 out of 7), China (74 out of 100) and France (13 out of 17)(Reference Mullan, Henderson and Kothe40–Reference De Lauzon-Guillain, Marques and Kadawathagedara43).

The two studies assessing adherence during lactation were conducted in Australia and the United States. The Australian study reported adherence scores around the mid-point (31 out of a maximum of 74), while the US study reported adherence scores slightly higher than the mid-point range (49–66 out of a maximum of 100)(Reference Morrison, Koh and Lowe28,Reference Nansel, Cummings and Burger29) . Of note is that the Australian study used specific references for lactating women which were higher serving recommendations.

Evaluations of adherence to guidelines during periconception were conducted in the Netherlands, Denmark and the United States, and each of these studies compared dietary behaviour with the FBDG for the general population. The Netherlands reported an adherence score at the mid-point of the maximum (three out of six)(Reference Twigt, Bolhuis and Steegers44). In the United States, two studies reported comparable results (scores of 63 and 66 out of 100)(Reference Yee, Silver and Haas45,Reference Willis, Hatch and Laursen46) , and Denmark achieved an adherence score of 4·2 out of 6, slightly closer to the maximum score compared with other countries(Reference Willis, Hatch and Laursen46).

Studies reporting adherence to specific food groups

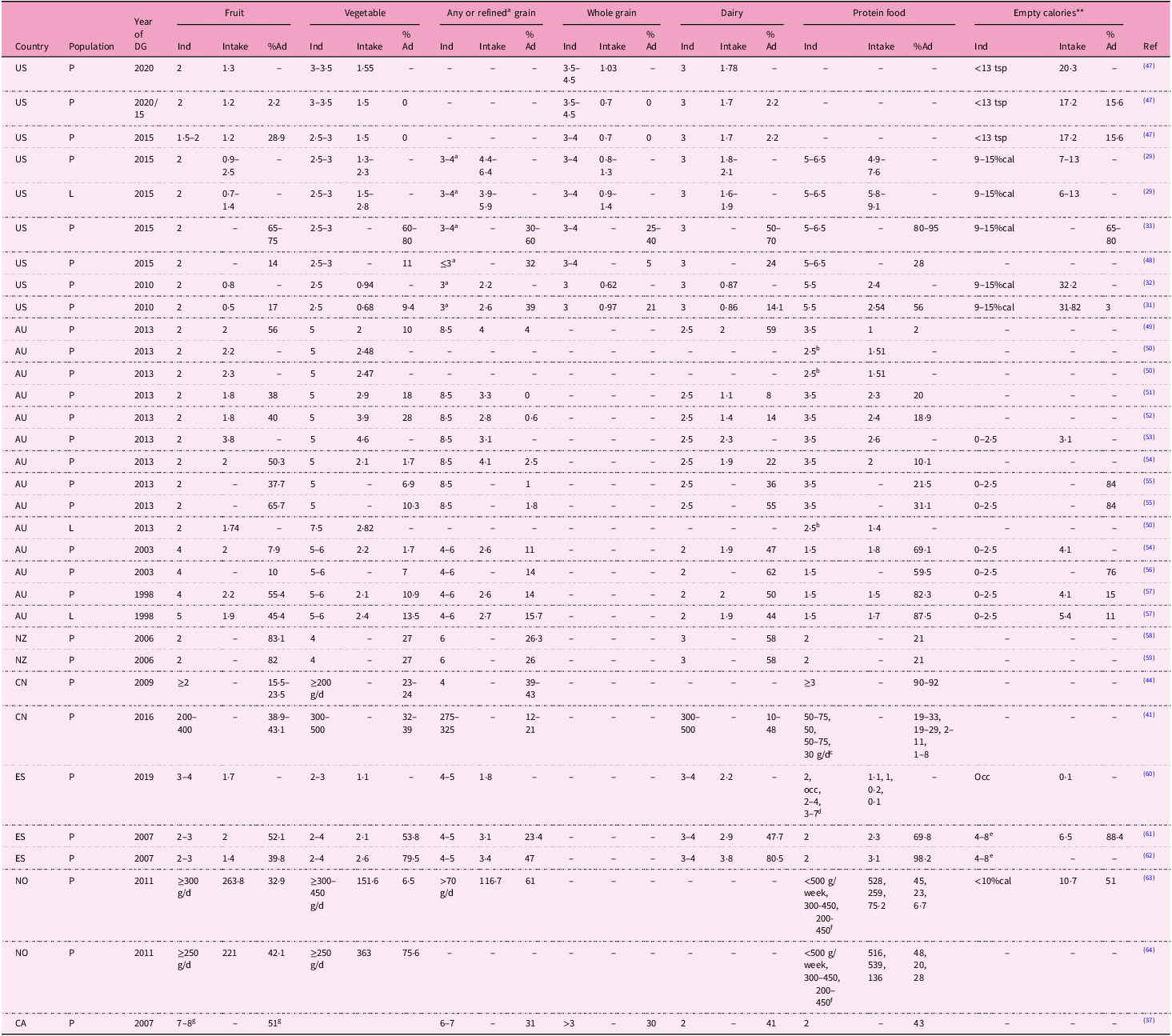

A number of studies report adherence to individual food groups or food categories spanning from 2011 to 2023. These have been outlined in Table 3, with small variations from country to country. This variation may stem from the 12-year gap in study periods, potentially influenced by any updates in FBDG during that timeframe. The columns in Table 3 describe the food group and indicators together with levels of adherence. It is important to note that the recommended ranges used as indicators (e.g. number of grain servings/d) often depend on the calorie intake of the study population, which can be narrower than the ranges specified in the guidelines. Intake is reported as mean/median, while adherence is presented as a proportion (%).

Table 3. Adherence of pregnant and lactating women to specific food group recommendations

US, United States; AU, Australia; NZ, New Zealand; CN, China; ES, Spain; NO, Norway; CA, Canada. P, pregnancy; L, lactation; Ind, indicators; %Ad, proportion of adherence; Occ, occasionally. –, no value reported. All units were serving/d except for the United States and otherwise stated. Column ‘Empty calories’ represents added sugar in the United States, discretionary choice in Australia, sweets and sweetened beverages in Norway and Spain; arefined grain, bfish only, cmeat and poultry, egg, fish, bean and nut, dpoultry, fish, eggs, red and processed meat, legume, nut; enon-alcoholic low-sugar drink; fred meat, fish, fatty fish; gfruit and vegetable.

Only eight countries have reported adherence for each food group, including the United States, Australia, New Zealand, the Netherlands, China, Spain, Norway and Canada. Therefore, these results may not relate to LMIC. Of all the reports, only three reported adherence during lactation. Currently, only one study reflects adherence of pregnant women to the 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) in the United States during pregnancy, cautioning against generalisations.

Observed adherence to fruit recommendations: Indicators that have been used across countries are relatively uniform, mostly around 2 servings/d. Fruit intake ranges from 0·5 to 2 servings, with adherence rate ranging from 2% to 75% in the United States(Reference Nansel, Cummings and Burger29,Reference Ferranti, Hartman and Elliott31–Reference Bodnar, Odoms-Young and Kirkpatrick33,Reference Filatava, Overton and El Habbal47,Reference Dolin, Gross and Deierlein48) , 10% to 65% in Australia(Reference Harper, Smythe and Wong51,Reference Slater, Rollo and Szewczyk52,Reference Mishra, Schoenaker and Mihrshahi54–Reference Blumfield, Hure and Macdonald-Wicks57) , 40% to 52% in Spain(Reference Jardi, Aparicio and Bedmar60–Reference Olmedo-Requena, Gomez-Fernandez and Mozas-Moreno62), 30% to 40% in Norway(Reference von Ruesten, Brantsaeter and Haugen63,Reference Saunders, Rehbinder and Lodrup Carlsen64) and up to 83% in New Zealand(Reference Lawrence, Wall and Bloomfield58,Reference Morton, Grant and Wall59) .

Observed adherence to vegetable recommendations: For vegetable consumption, the intake indicators used were varied, ranging from 2–3 to 5–6 servings/d. However, despite these higher indicators, the average intake of vegetables is only slightly higher than fruits. In Australia, where the indicator is higher (five to six servings), adherence rates range from 2% to 28%(Reference Harper, Smythe and Wong51,Reference Slater, Rollo and Szewczyk52,Reference Mishra, Schoenaker and Mihrshahi54–Reference Blumfield, Hure and Macdonald-Wicks57) . Specifically for lactation, the recommended serving is 7·5 servings/d, yet the adherence rate is only 3%(Reference Nathanson, Hill and Skouteris50). In Spain, where the serving recommendations are lower and have a wider range (2–4 servings/d), adherence rates range between 54% and 80%(Reference Rodriguez-Bernal, Ramon and Quiles61,Reference Olmedo-Requena, Gomez-Fernandez and Mozas-Moreno62) .

Observed adherence to grains recommendations: In Australia, indicators used to measure adherence to grain consumption recommendations rose from 4–6 servings in the 2003 guidelines to 8·5–9 servings in 2013(22). However, smaller serving sizes were specified for some grain types. Nevertheless, actual grain intake in Australia was approximately 2.6 servings in 2003 and 3–4 servings in 2013, significantly below the recommended levels(Reference Harper, Smythe and Wong51–Reference Blumfield, Hure and Macdonald-Wicks57). As a result, the adherence rate was only approximately 11–16% for the 2003 guidelines(Reference Mishra, Schoenaker and Mihrshahi54,Reference Bookari, Yeatman and Williamson56,Reference Blumfield, Hure and Macdonald-Wicks57) and less than 5% when using the 2013 guidelines as a reference(Reference Malek, Umberger and Makrides49,Reference Harper, Smythe and Wong51,Reference Slater, Rollo and Szewczyk52,Reference Mishra, Schoenaker and Mihrshahi54,Reference Lee, Muggli and Halliday55) . Norway recommends a minimum grain consumption of 70 g/d, with a reasonably high adherence rate of 61%(Reference von Ruesten, Brantsaeter and Haugen63). Refined grain consumption adherence was only reported by some studies in the United States, with an adherence rate of approximately 30–60% due to overconsumption (>3 servings/d)(Reference Dolin, Gross and Deierlein48). Specific amounts of recommended whole grain intake are provided only by the United States and Canada, with reported consumption as low as 1 serving/d (0–25% adherence), despite recommendations ranging from 3 to 4·5 servings/d(Reference Nansel, Cummings and Burger29,Reference Ferranti, Hartman and Elliott31–Reference Bodnar, Odoms-Young and Kirkpatrick33,Reference Jarman, Bell and Nerenberg37,Reference Filatava, Overton and El Habbal47,Reference Dolin, Gross and Deierlein48) .

Observed adherence to dairy recommendations: Indicators for dairy intake in the United States were 3 cups/d, while in Australia it was 2–2·5 servings/d(Reference Filatava, Overton and El Habbal47,Reference Dolin, Gross and Deierlein48,Reference Harper, Smythe and Wong51,Reference Slater, Rollo and Szewczyk52,Reference Mishra, Schoenaker and Mihrshahi54–Reference Blumfield, Hure and Macdonald-Wicks57) . Adherence falls to approximately 50% or less, as the mean/median intake is less than two servings. In Spain, the recommendation for dairy consumption is higher (3–4 servings/d), followed by actual intake ranging from 2·2 to 3·8 servings (adherence 50–80%)(Reference Jardi, Aparicio and Bedmar60–Reference Olmedo-Requena, Gomez-Fernandez and Mozas-Moreno62).

Observed adherence to protein foods recommendations: Indicators for protein food vary, with some studies referring to guidelines that specify sources such as seafood and/or plant protein. Adherence for 5–6·5 oz/d in the United States is generally higher, ranging from 2·5 to 9 oz/d (adherence 30–80%)(Reference Ferranti, Hartman and Elliott31–Reference Bodnar, Odoms-Young and Kirkpatrick33,Reference Dolin, Gross and Deierlein48) , compared with Australia with indicators 1·5–3·5 servings/d, intake ranging from 1 to 2·6 servings/d (adherence 10–30%)(Reference Malek, Umberger and Makrides49,Reference Harper, Smythe and Wong51,Reference Slater, Rollo and Szewczyk52,Reference Mishra, Schoenaker and Mihrshahi54,Reference Lee, Muggli and Halliday55) . Adherence to fish intake recommendations is generally lower compared with meat or poultry. Australia and China provide specific serving recommendations for fish, namely 2·5 servings/d and 50–75 g/d, respectively. However, actual intake is lower, with Australia consuming approximately 1·5 servings/d and China exhibiting adherence rates of 2–11%(Reference Ding, Xu and Zhong41,Reference Nathanson, Hill and Skouteris50) . Norway distinguishes its fish intake recommendations between fatty fish (200–450 g/week) and other fish (300–450 g/week), with fatty fish intake ranging from 75 to 136 g and other fish intake from 260 to 540 g(Reference von Ruesten, Brantsaeter and Haugen63,Reference Saunders, Rehbinder and Lodrup Carlsen64) . Spain combines serving recommendations with other protein foods, specifying 2 servings/d for poultry, fish, and eggs, with actual intake averaging approximately 1 serving/d(Reference Jardi, Aparicio and Bedmar60).

Observed adherence to ‘empty’ calorie recommendations: This category encompasses what is termed ‘discretionary choices’ in Australia, ‘added sugar’ in the latest US guidelines and ‘sweets and sweetened beverages’ in Spain and Norway. The recommended limit used for added sugar, set at less than thirteen teaspoons in the United States, faces low adherence (15%) as the mean intake reaches seventeen teaspoons(Reference Filatava, Overton and El Habbal47). Meanwhile, adherence to recommendations for discretionary choices, set at less than 2·5 servings, presents mixed reports, ranging from 10% to 84% in Australia(Reference Lee, Muggli and Halliday55–Reference Blumfield, Hure and Macdonald-Wicks57). The intake in this category ranges from seventeen to twenty teaspoons or, when defined in percentage of calories, is between 6% and 30%, or 3–5 servings/d.

Adherence to other recommendations

Several other recommendations were scrutinised, including the consumption of an extra serving from any food group, water intake, alcohol consumption, diet variety, coffee consumption and supplementation. It is important to acknowledge that only five studies from five countries documented the analysis of these recommendations: China examined drinking water, alcohol consumption and diet variety(Reference Ding, Xu and Zhong41,Reference Pan, Karatela and Lu65) ; Norway investigated adherence to coffee and alcohol consumption(Reference Saunders, Rehbinder and Lodrup Carlsen64); Spain scrutinised alcohol consumption(Reference Jardi, Aparicio and Bedmar60); Canada assessed whether women consume extra servings during pregnancy(Reference Jarman, Bell and Nerenberg37); and Sri Lanka observed adherence to iron and folic acid supplementation(Reference Pathirathna, Wimalasiri and Sekijima30). All studies exclusively focus on pregnancy, lacking any analysis of other recommendations during lactation.

Canada suggests two to three additional servings of food, yet <1% of women reported following this pregnancy-specific guidance across food groups(Reference Jarman, Bell and Nerenberg37). Only one study in China analysed water consumption, revealing an intake of approximately 1000 ml from the recommended intake of ≥1700 ml(Reference Pan, Karatela and Lu65). Studies in China and Spain show high adherence to zero alcohol consumption during pregnancy(Reference Jardi, Aparicio and Bedmar60,Reference Pan, Karatela and Lu65) . The study in Norway found an adherence proportion of 56.5%, but the mean alcohol intake was only 0·1 g/d(Reference Saunders, Rehbinder and Lodrup Carlsen64). Diet variety, as measured in the study in China using twelve categories of food groups, had a mean score of −2·79, with the best value of zero, indicating that two to three food groups were not eaten in amounts of at least 25 g daily(Reference Pan, Karatela and Lu65). Coffee consumption, measured in the study in Norway with an ideal range of 170 to a maximum of 340 g/d, had a population adherence of 59%(Reference Saunders, Rehbinder and Lodrup Carlsen64). Iron and folic acid supplementation, analysed in the study in Sri Lanka, showed high adherence at 80·1%(Reference Pathirathna, Wimalasiri and Sekijima30).

Factors related to adherence

Among the forty-seven published articles that measure adherence to dietary guidelines, a detailed exploration of factors influencing adherence was conducted in thirty studies only. Twenty-five studies exclusively focused on pregnancy; two studies encompassed both pregnancy and lactation, one focused on lactation and two focused on preconception. Geographically, these analyses were predominantly conducted in HIC and UMIC, except for Sri Lanka (LMIC), where the focus was solely on supplementation(Reference Pathirathna, Wimalasiri and Sekijima30).

Positive factors: The factors consistently demonstrating a positive correlation with adherence include advanced maternal age(Reference Ferranti, Hartman and Elliott31,Reference Wang, Yim and Lindsay34,Reference Kadawathagedara, Ahluwalia and Dufourg42,Reference Yee, Silver and Haas45,Reference Morton, Grant and Wall59–Reference von Ruesten, Brantsaeter and Haugen63,Reference Nguyen, de Barse and Tiemeier66,Reference Wei, Li and Lei67) , higher levels of education(Reference Morrison, Koh and Lowe28,Reference Francis, Dabelea and Shankar35,Reference Jarman, Bell and Nerenberg37,Reference Willis, Hatch and Laursen46,Reference Lee, Muggli and Halliday55,Reference Jardi, Aparicio and Bedmar60,Reference Rodriguez-Bernal, Ramon and Quiles61,Reference Saunders, Rehbinder and Lodrup Carlsen64,Reference Wei, Li and Lei67,Reference Laursen, Johannesen and Willis68) , employment status(Reference Pathirathna, Wimalasiri and Sekijima30,Reference Kadawathagedara, Ahluwalia and Dufourg42,Reference Roman-Galvez, Martin-Pelaez and Hernandez-Martinez69) , elevated social class(Reference Jardi, Aparicio and Bedmar60,Reference Olmedo-Requena, Gomez-Fernandez and Mozas-Moreno62,Reference von Ruesten, Brantsaeter and Haugen63) , women actively supplementing with multivitamins during pregnancy(Reference Willis, Hatch and Laursen46,Reference Wei, Li and Lei67,Reference Malek, Umberger and Makrides70) and a history of certain medical conditions such as eating disorders, anaemia or having delivered a low-birth-weight (LBW) infant in a prior birth(Reference Pathirathna, Wimalasiri and Sekijima30,Reference Nguyen, de Barse and Tiemeier66) .

Further exploration into these studies unveils additional factors that positively correlate with adherence. These include English-speaking women(Reference Morrison, Koh and Lowe28), higher energy and caffeine intake(Reference Laursen, Johannesen and Willis68), full-term birth(Reference Wei, Li and Lei67), prolonged breastfeeding duration(Reference von Ruesten, Brantsaeter and Haugen63), familiarity with dietary recommendations(Reference Bookari, Yeatman and Williamson56), self-identification as a healthy eater(Reference Malek, Umberger and Makrides70), holding a healthy eating intention(Reference Malek, Umberger and Makrides70), receiving risk reduction advice (specifically for gestational diabetes) from a healthcare professional(Reference Morrison, Koh and Lowe28), and the presence of specific medical conditions that influence dietary choices, such as diabetes resulting in reduced added sugar consumption, and pre-eclampsia prompting increased whole-grain intake(Reference Filatava, Overton and El Habbal47).

Negative factors: Inversely, factors such as smoking(Reference Francis, Dabelea and Shankar35,Reference Yee, Silver and Haas45,Reference Willis, Hatch and Laursen46,Reference Malek, Umberger and Makrides49,Reference James-McAlpine, Vincze and Vanderlelie53,Reference Jardi, Aparicio and Bedmar60,Reference Olmedo-Requena, Gomez-Fernandez and Mozas-Moreno62,Reference von Ruesten, Brantsaeter and Haugen63,Reference Laursen, Johannesen and Willis68,Reference Roman-Galvez, Martin-Pelaez and Hernandez-Martinez69,Reference Koivuniemi, Hart and Mazanowska71) , alcohol consumption(Reference Jardi, Aparicio and Bedmar60,Reference Saunders, Rehbinder and Lodrup Carlsen64) , residence in metropolitan areas(Reference Malek, Umberger and Makrides49,Reference Malek, Umberger and Makrides70) and elevated BMI or obesity, including a high waist circumference(Reference Francis, Dabelea and Shankar35–Reference Jarman, Bell and Nerenberg37,Reference Willis, Hatch and Laursen46,Reference Filatava, Overton and El Habbal47,Reference Malek, Umberger and Makrides49,Reference Lee, Muggli and Halliday55,Reference von Ruesten, Brantsaeter and Haugen63,Reference Laursen, Johannesen and Willis68) , were consistently associated with lower adherence.

Furthermore, limited studies suggest that factors such as increased hours spent watching TV(Reference Olmedo-Requena, Gomez-Fernandez and Mozas-Moreno62), higher consumption of ultra-processed foods(Reference Nansel, Cummings and Burger29), elevated intake of sugar-sweetened beverages(Reference Willis, Hatch and Laursen46), twin pregnancies(Reference Filatava, Overton and El Habbal47), the use of hormonal contraception(Reference Willis, Hatch and Laursen46), reliance on public insurance(Reference Yee, Silver and Haas45), and single motherhood(Reference Kadawathagedara, Ahluwalia and Dufourg42) are inversely correlated with adherence.

Examining mixed findings brings factors such as income and country of origin to light. While five studies reported a positive correlation between income and adherence(Reference Jarman, Bell and Nerenberg37,Reference Yee, Silver and Haas45,Reference Willis, Hatch and Laursen46,Reference Malek, Umberger and Makrides49,Reference Wei, Li and Lei67) , one study found low income associated with adherence, particularly in bread/cereal, meat and egg intake(Reference Morton, Grant and Wall59). Similarly, the correlation with country of origin exhibited mixed results, with two studies from Australia indicating a positive correlation between being born in Australia and higher adherence, particularly in fruit, vegetables and milk. However, no correlation was found in grain or lean meat, poultry, fish and beans(Reference Malek, Umberger and Makrides49,Reference Malek, Umberger and Makrides70) . A study in Spain found Spanish women to be less adherent than foreign-born women(Reference Rodriguez-Bernal, Ramon and Quiles61). Another dimension of mixed findings relates to physical activity. Seven studies reported a positive correlation with adherence(Reference Morrison, Koh and Lowe28,Reference Malek, Umberger and Makrides49,Reference Olmedo-Requena, Gomez-Fernandez and Mozas-Moreno62,Reference von Ruesten, Brantsaeter and Haugen63,Reference Wei, Li and Lei67–Reference Roman-Galvez, Martin-Pelaez and Hernandez-Martinez69) , whereas one study in the United States found the opposite(Reference Francis, Dabelea and Shankar35). However, these studies employed varying indicators for physical activity, such as a binary variable below or above 150 min/week, adherence to physical activity guidelines pre-pregnancy (≥30 min of exercise on ≥5 d each week), or numeric total metabolic equivalent (MET) of physical activity (h/week), and exercise frequency assessed in a week. Lastly, factors such as parity or the presence of older children also presented mixed findings, with three studies reporting a positive correlation(Reference Morton, Grant and Wall59,Reference Laursen, Johannesen and Willis68,Reference Koivuniemi, Hart and Mazanowska71) and three studies indicating a negative correlation(Reference Kadawathagedara, Ahluwalia and Dufourg42,Reference Willis, Hatch and Laursen46,Reference Wei, Li and Lei67) .

Outcomes associated with adherence

From forty-seven full-text articles, seventeen studies analysed adherence and outcomes exclusively during pregnancy and three studies preconception period (three studies). Interestingly, none of the discussed outcomes was associated with dietary adherence during lactation. Notably, this subset of studies was exclusively conducted in HIC and UMIC.

Several studies have explored the relationship between dietary patterns and pregnancy-related health outcomes in different countries. In China and the United States, adherence to dietary guidelines was associated with a reduced risk of gestational hypertension(Reference Ding, Xu and Zhong41,Reference Yee, Silver and Haas45) . In Australia, a higher consumption of vegetables was linked to a lower incidence of hypertensive disorders(Reference James-McAlpine, Vincze and Vanderlelie53). Denmark’s adherence to the Nordic dietary pattern showed a significant association with lower rates of spontaneous abortion(Reference Laursen, Johannesen and Willis68). Additionally, following US guidelines was correlated with fewer prenatal depressive symptoms(Reference Wang, Yim and Lindsay34).

In the United States, a diet rich in vegetables was associated with a lower incidence of preeclampsia, while in Iceland, a higher intake of whole grains was linked to a decreased risk of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)(Reference Petersen, Naimi and Kirkpatrick32,Reference Tryggvadottir, Halldorsson and Landberg72) . Conversely, a study in China found that participants with GDM had a higher adherence score for animal food intake than those without GDM(Reference Pan, Karatela and Lu65). Lastly, adherence to US guidelines was associated with a lower frequency of postpartum haemorrhage requiring transfusion but a higher frequency of major perineal laceration and a greater risk of caesarean delivery(Reference Yee, Silver and Haas45).

Regarding child outcomes, adherence to the French diet positively correlated with neurodevelopment in children aged 1–3·5 years(Reference De Lauzon-Guillain, Marques and Kadawathagedara43). Inversely, a study in Norway found an inverse association between the diet and all child functions, but the estimated strength of each association was low(Reference Borge, Brantsaeter and Caspersen73). Adherence to US guidelines was associated with healthier metabolic conditions, such as lower levels of glucose, insulin, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) and adiponectin among boys only(Reference Francis, Dabelea and Shankar35). Adherence to seafood consumption in China was linked to higher birth weight(Reference Wei, Li and Lei67).

Discussion

This review highlights the disparities in the availability of dietary guidelines and supporting research for guideline evaluation in LMIC and LIC. It also highlights the shortage of research examining dietary practices related to guidelines during lactation. Approximately half of the countries lack FBDG, with only 15% offering specific guidelines for pregnant and lactating women. The availability of guidelines varies based on the country’s income level, and recommendations for pregnant and lactating women exhibit significant variability. Limited studies report adherence in LMIC and LIC, with a specific dearth of research focusing on lactation. There is a need for globally standardised guidelines tailored for pregnant and lactating women, addressing the absence of guidelines in half of the countries. It is crucial to prioritise and allocate funds for research in LMIC and LIC to comprehend dietary patterns, adherence barriers and health outcomes.

The reported low overall adherence indicates a widespread challenge in meeting dietary recommendations, suggesting a need for targeted interventions to enhance dietary practices on a global scale. The low adherence to consuming fruits and vegetables raises concerns. Despite the promotion of increased fruit and vegetable intake in dietary guidelines, national surveys indicate suboptimal dietary habits that are not improving over time. Various obstacles, such as economic, physical and behavioural barriers, need to be considered when exploring potential strategies to enhance fruit and vegetable consumption. It is essential to consider the feasibility of different approaches to encourage an increase in the intake of fruits and vegetables(Reference Woodside, Nugent and Moore74). The mixed adherence to grains, with particularly low adherence to whole grains, emphasises variations in dietary choices and preferences, presenting an opportunity for improvement in promoting the nutritional benefits of whole grains. Furthermore, Meynier et al. propose various suggestions to boost the intake of whole grains for general population. These recommendations encompass enhancing the accessibility and diversity of food options containing whole grains, improving their sensory appeal, reducing purchase costs, and enhancing communication and labelling to facilitate consumers in easily identifying products containing whole grains(Reference Meynier, Chanson-Rolle and Riou75). Moderate adherence to dairy, meat and added sugar reflects the diversity of dietary patterns and cultural influences across countries, indicating room for improvement in balancing the consumption of these food groups. Notably, the low adherence to fish consumption is significant, considering the nutritional benefits of fish(Reference Chen, Jayachandran and Bai76). Addressing barriers and promoting the advantages of fish consumption could be crucial for enhancing adherence to this food group. Research conducted in the UK and Singapore indicates that factors positively linked to increased fish consumption in the general population include younger age, affordability, recognition of the health benefits of fish, health-related concerns about meat, and religious considerations. Conversely, concerns about sustainability are negatively associated with fish consumption(Reference Supartini, Oishi and Yagi77).

The analysis of demographics and associated factors with adherence to dietary guidelines reveals recognisable patterns in social determinants of health. Older individuals exhibit better adherence, potentially reflecting an increased awareness of health-related issues and a stronger commitment to a healthy lifestyle as people age. Moreover, higher educational levels correlate with improved adherence, suggesting that a greater understanding of nutrition among those with more education influences dietary choices. Employment status positively influences adherence, possibly due to stable routines, access to resources and a heightened awareness of the importance of a balanced diet for productivity. The use of supplements is also linked to better adherence, indicating a conscious effort to supplement nutritional intake for overall health. Conversely, negative correlations show that individuals who smoke or consume alcohol are less likely to adhere to dietary guidelines, potentially due to an overall unhealthy lifestyle associated with these habits. A high BMI is negatively correlated with adherence, implying that individuals with higher BMI values may struggle with adherence due to dietary habits contributing to weight-related issues. Additionally, public insurance correlates negatively with adherence, suggesting that individuals with public insurance exhibit lower adherence, possibly influenced by socioeconomic factors and limited access to nutritional resources.

The relationship between adhering to dietary guidelines and health outcomes remains unclear, with varying research findings. This review suggests that following specific dietary patterns plays a role in meeting daily nutritional needs, regulating metabolic and hormonal functions, and minimising abnormalities during pregnancy and lactation. The exact mechanisms linking dietary patterns to health outcomes remain uncertain due to the complexity and differences in substances present in each pattern of adherence to different guidelines. The review compiles the positive associations between adherence and a reduced risk of gestational hypertension, spontaneous abortion, preterm birth and low birth weight. Despite these analyses, it is crucial to note the limited exploration of intermediate nutritional outcomes such as anaemia and micronutrient deficiency in mothers and children. Additionally, the growth of children during the initial two years of life and beyond remains an understudied area within the current knowledge. The recommendation is to encourage and support longitudinal studies that delve into long-term outcomes, child growth and micronutrient deficiencies for deeper insights.

To our knowledge, this comprehensive review is the first of its kind, systematically compiling and comparing dietary guidelines for pregnant and lactating women across different countries. By undertaking such a holistic approach, the study provides valuable insights into the variations and commonalities in recommendations, offering a global perspective on nutritional advice for this specific population. Another notable strength lies in the examination of both overall and specific food adherence over an extended period. This temporal analysis allows the observation of adherence dynamics, particularly in response to changes in dietary guidelines in certain countries. However, it is essential to acknowledge certain limitations in this study. Our focus is on examining how national dietary guidelines, which specifically target pregnant and lactating women, might not capture all pertinent advice for pregnancy and lactation that can often be provided in separate documents or leaflets. This limitation highlights the necessity for a more streamlined approach to ensure that all the guidelines for pregnant and lactating women are clearly communicated via a central platform. Moreover, the lack of standardised methods for measuring adherence across studies introduces variability, posing a challenge in making direct comparisons and potentially impacting the accuracy of reported adherence rates. Future research could benefit from further addressing these limitations to enhance the findings’ reliability and applicability.

Conclusion

This comprehensive review reveals significant disparities in the availability of dietary guidelines for pregnant and lactating women across LMIC. The observed variations in recommendations, coupled with a dearth of research on adherence, particularly during lactation, highlight the critical need for standardised guidelines that can be implemented in LMIC in particular, where specific FBDG for women of childbearing age may not exist. Additionally, it is important to support LMIC and LIC in developing their own FBDG tailored to their populations based on nutritional needs, food availability, affordability and dietary habits. The low overall adherence to dietary recommendations highlights a global challenge, necessitating targeted interventions, especially in promoting fruit, vegetable, whole grain and fish consumption. Factors influencing adherence reveal familiar patterns, emphasising the role of age, education, employment status and lifestyle habits. While positive associations between adherence and reduced risks of gestational complications are noted, the review calls for further exploration of intermediate nutritional outcomes. This study serves as a crucial foundation, urging prioritised research and the development of universally applicable strategies to enhance dietary practices for pregnant and lactating women worldwide.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954422424000283.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to UWA Library Support Staff for their valuable input during the review process.

Financial support

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding and scholarship provided by the Australian Government Research Training Program and the University of Western Australia for supporting this research.

Competing interests

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist.

Authorship

Conceptualisation: S.R., K.M., G.A. and S.H.; methodology: S.R., K.M., G.A. and S.H.; investigation: S.R.; visualisation: S.R. and K.M.; writing – original draft: S.R.; writing – review and editing: K.M., G.A. and S.H.