No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

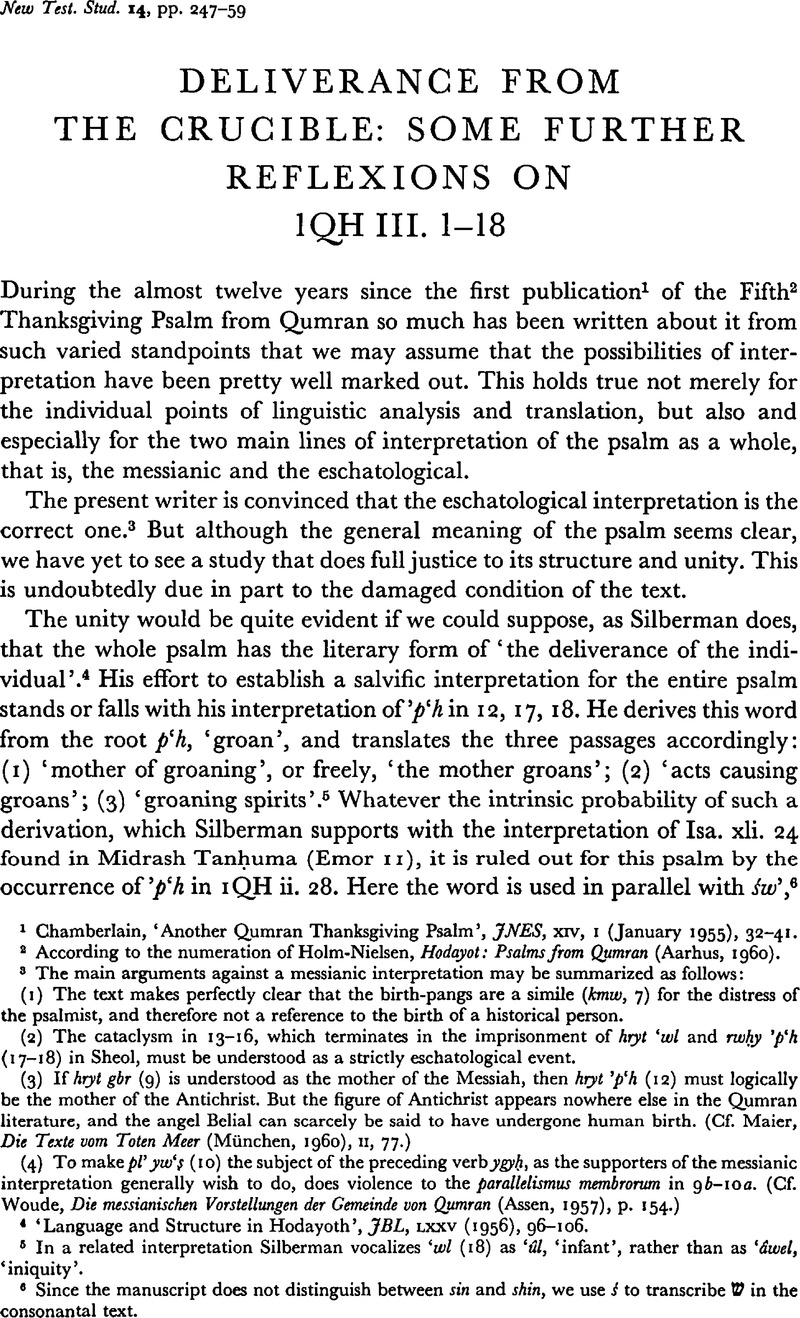

page 247 note 1 Chamberlain, , ‘Another Qumran Thanksgiving Psalm’, JJVES, XIV, 1 (January 1955), 32–41.Google Scholar

page 247 note 2 According to the numeration of Holm-Nielsen, Hodayot: Psalms from Qumran (Aarhus, 1960).

page 247 note 3 The main arguments against a messianic interpretation may be summarized as follows:

(1) The text makes perfectly clear that the birth-pangs are a simile (kmw, 7) for the distress of the psalmist, and therefore not a reference to the birth of a historical person.

(2) The cataclysm in 13–16, which terminates in the imprisonment of hryt ‘wl and rwḥy ’p‘h (17–18) in Sheol, must be understood as a strictly eschatological event.

(3) If hryt gbr (9) is understood as the mother of the Messiah, then hryt ’p‘h (12) must logically be the mother of the Antichrist. But the figure of Antichrist appears nowhere else in the Qumran literature, and the angel Belial can scarcely be said to have undergone human birth. (Cf. Maier, Die Texte vom Toten Meer (München, 1960), 11, 77.)

(4) To make pl’ yw‘ ⊡ (10) the subject of the preceding verb ygyḥ, as the supporters of the messianic interpretation generally wish to do, does violence to the parallelismus membrorum in 9b–10a. (Cf. Woude, Die messianischen Vorstellungen der Gemeinde von Qumran (Assen, 1957), p. 154.)

page 247 note 4 ‘Language and Structure in Hodayoth’, JBL, LXXV (1956), 96–106.Google Scholar

page 247 note 5 In a related interpretation Silberman vocalizes ‘wl (18) as ‘ûl, ‘infant’, rather than as ‘âwel, ‘iniquity’.

page 247 note 6 Since the manuscript does not distinguish between sin and shin, we use ś to transcribe ש in the consonantal text.

page 248 note 1 Cf Glanzman, , ‘Sectarian Psalms from the Dead Sea’, TS, xiii (1952), 508, 523.Google Scholar

page 248 note 2 Art. cit. p. 103 n.

page 248 note 3 Cf. Maier, op. cit. 11, 73: ‘es geht um das Gelingen oder Scheitern der eschatologischen Hoffnung, um die Situation der Krise.’ We believe, however, that this ‘situation of crisis’, involving both communities, requires closer consideration than Maier grants to it. We do not believe that through the pregnancy simile ‘lediglich die gefährliche Lage (emphasis ours) des Beters illustriert wird’. The simile of a woman in labour is, to be sure, in a certain sense co-ordinated with the previous similes of a ship at sea and a besieged city, but it is nevertheless distinctive. We recognize the importance of Delcor's observation (even though we do not draw from it the same conclusion): ‘II (the psalmist) developpe cette dernière image de façon inhabituelle avec un luxe de détails que nous n'avions pas dans l'A.T.’ (Les Hymnes de Qumran (Paris, 1962), pp. 121–2).

page 248 note 4 Only in the single word wt⊡ylny (5) does the psalmist mention the real act of divine deliverance signified by the simile in 10. Nowhere does he tell us how God rescues his faithful from the distress.

page 248 note 5 The second hryh is still present in 18, but she is no longer part of a simile; she has become an allegorical designation for the hostile community. Therefore, she is no longer said to be hryt ’p‘h, ‘the woman pregnant with nought’, i.e. the woman who is unable to bring the child to term (cf. Maier, op. cit. 11, 77: ‘So ist es also eine Art Fehl-bzw. Totgeburt’), or, perhaps, the victim of a false pregnancy, but hryt ‘wl, ‘the woman pregnant with iniquity’. In other words, the second hryh is no longer a generalized figure whose tragic disappointment symbolizes the frustration of the eschatological hope of the enemy; she has become a particularized evil figure, designating the rival group. We therefore believe that Maier is mistaken when he goes on to say: ‘(Totgeburt), bei der auch die Gebärende (die gegnerische Gemeinde) zugrundegeht.’ This is reading the fate of the allegorical hryt ‘wl back into the simile, which, in itself, expresses merely frustration and disappointment, following upon pain and crisis. At the same time, the parallelism in the final verse between hryt ‘wl and rwḥy ’p‘h provides a link in the transition from simile to allegory without which confusion for the reader would result. Nevertheless, this coupling of two compound expressions, the one allegorical and the other literal, does not constitute a direct parallelism between ‘wl and ’p‘h. We therefore find no justification for Delcor's conclusion: ‘Cette expression parallèle qui désigne la même réalité constitue un argument contre la traduction de certains auteurs: “Celle qui a conçu le néant”’ (op. cit. p. 114). The two expressions do not designate the same reality: hryt ‘wl designates the hostile community, and rwhy 'p‘h the evil angels.

page 249 note 1 Cf. Maier, op. cit. 11, 73: ‘So ist vielleicht geraten, auch hier das “Ich” nicht streng individuell, sondern als “typisches Ich”, für die Geraeinde zu verstehen.’

page 249 note 2 The solidarity between the psalmist and the community would be especially clear if he is actually the Teacher of Righteousness, the founder of the Qumran sect.

page 249 note 3 Delcor, op. cit. p. 109.

page 249 note 4 Kautzsch, and Cowley, , Gesenius' Hebrew Grammar (Oxford, 1956), p. 484 n.Google Scholar

page 250 note 1 m⊡‘ dm and yśmy‘w qwlm (17). Possibly they are also alluded to in ḥkmyhm Imw (14), which would then refer to the theological leaders of the opposing sect. Chamberlain identifies ‘our mysterious “they”’ with ‘angelic (or demonic) powers whose function it is to open and close the gates of Sheol’ (art. cit. p. 39). If this is correct, then we would have yet another correspondence between simile and reality in the psalm: Yahweh delivers the child from the womb, and the spirits lock up the sect's enemies in Sheol. However, it seems from 18 that the evil spirits are themselves locked up in Sheol, and yptḥw (16) can be vocalized as Niph. as well as Qal. Moreover, nothing prevented the psalmist from naming the ‘angelic (or demonic) powers’, if he had really had them in mind. It seems better, therefore, to understand all the occurrences in the psalm of the anonymous ‘they’ as having the same reference, i.e. to the enemies of the Qumran sect.

page 250 note 2 Kuhn, Konkordanz zu den Qumrantexten (Gottingen, 1960), p. 133 n.: ‘Wahrscheinlich ist wḥbly mr⊡ Fehler der Hs. für wḥbl nmr⊡.’Google Scholar

page 250 note 3 By the ‘realistic’ portion of the psalm, we mean the part where events, of whose reality the psalmist was convinced, are depicted directly and not by means of a simile.

page 250 note 4 So Silberman, art. cit. p. 98.

page 250 note 5 Gleen Hinson has maintained (RQ, VI (1960), 201) that the three themes of the foundering ship (6), the besieged city (7), and the woman in labour (7) which are mentioned in the ‘introduction’ are successively developed, but in inverted order, in the ‘body’ of the psalm. 13–16 return to the similes of the besieged city and the ship on the high seas. But this interpretation fails to note that in 13–16 we do not have two separate pictures but one unified picture of a deluge, which has abolished the distinction between sea and land.

page 250 note 6 In the parallel in 1 QH iii. 29 ff. (cf. Luke xvii. 29) where the cosmic confusion is caused by fire instead of water. Delcor asserts: ‘L’ enfantement de l'Aspic est accompagné d'un grand cataclysme, avec des inondations et du tonnerre' (op. cit. p. 114). But the clear transition after pl⊡wt (12) on the one hand and the unity of 13–18 on the other shows us that the cataclysm is to be associated not with the simile but with the reality, i.e. not with the birth of 'p‘h (which is nowhere described) but with the imprisonment of hryt ‘wl and kwl rwḥy ’p‘h.

page 251 note 1 In view of the virtual equation of ś'wl (16) and thwm (17) in this passage (cf. 'bdwn and thwm in iii. 32), the question arises whether the fate which the psalmist describes in 18 as eternal imprisonment in Sheol may not concretely mean drowning in the deluge.

page 251 note 2 We hesitate to use a word like ‘historical’, which has no foundation whatever in the thinking of the Qumran community. The sect conceived itself to be already living in ‘the last days’. And yet some word is necessary to distinguish the actual situation of the psalmist and the anticipated future activity of the sect from that moment when, it was believed, God would personally intervene. In 1QM, for example, the faithful win three victories in the eschatological war and then suffer three defeats, but the final decision comes only in the seventh lsquo;lot’, in which God alone brings the victory. Similarly, we speak of the whole of Mark xiii as ‘the eschatological discourse’, and yet there is a clear caesura in Mark xiii. 24 ff. with the description of the cosmic events which precede the coming of the Son of Man and put an end to all human activity. One could express this distinction with the terms ‘eschatological in the broad sense’ and ‘eschatological in the strict sense’, but these terms are evidently too cumbersome and have no surer foundation in Qumran than ‘historical’.

page 251 note 3 Cf. Chamberlain, art. cit. p. 33: ‘At the time 1QH 6 (= 1QH iii. 1–18) was written, all Judaism, including the sect, was apparently under heavy persecution from without.’

page 251 note 4 Cf. Maier, op. cit. II, 74: ‘analog dem kritischen Punkt im Vorgang der Geburt.’

page 251 note 5 Mansoor, , The Thanksgiving Hymns (Leiden, 1961), pp. 112 n.–13 n.Google Scholar

page 252 note 1 Delcor, op. cit. pp. 110–11.

page 252 note 2 Mansoor, op. cit. p. 112.

page 252 note 3 Delcor, op. cit. p. no. 110.

page 252 note 4 The plural number mśbryh is against its being understood as ‘womb’, which is otherwise always singular, and the meaning ‘with’, i.e. ‘in addition to’, for the preposition ‘l is difficult.

page 252 note 5 Cf Thomas, , ‘A Consideration of Some Unusual Ways of Expressing the Superlative in Hebrew’, VT, III (1953), 209–24. This study is limited, to be sure, to showing that the use mwt and ś’wl can have a superlative sense. However, it seems reasonable to suppose that śḥt can also be used in this way.Google Scholar

page 252 note 6 Delcor, op. cit. p. 114.

page 252 note 7 Koehler-Baumgartner, , Lexicon in Veteris Testamenti Libros (Leiden, 1953), pp. 271–2.Google Scholar

page 252 note 8 Bardtke translates the word in 8 and 9 ‘Leibesfrucht’. (‘Die Loblieder von Qumran’, ThLz, LXXXI (1956), col. 592.)

page 252 note 9 Holm-Nielsen, op. cit. p. 54. However, since the pregnancy simile represents the situation of distress which is common to both communities, ḥbl nmr⊡ should be translated the same way in all three occurrences.

page 252 note 10 See note 5 above.

page 252 note 11 However, since ḥbl is common to both communities, this connotation of (condemnatory) judgment is not the predominant one.

page 253 note 1 Maier, op. cit. n, 74: ‘Beiden (d. h. Krampfwellen und Wasserwellen) gemeinsam ist die Verwendung für die Beschreibung von höchster Todesgefahr.’ This is also the ‘tertium comparationis’ in the similes of the foundering ship and the besieged city in 6–7.

page 253 note 2 The finding that the psalmist seems to have seen a connexion between the convulsions of the cosmos and the convulsions of a woman in labour raises the question whether the repeated use of the verb hmh (13, 15) and the cognate noun hmwn (13, 14, 16) can be explained in the same way. Did the psalmist see a similarity between the roaring of the clouds and the water, and the groaning of a woman in labour?

page 253 note 3 So Chamberlain, art. cit. p. 35.

page 254 note 1 Dictionary, s.v.

page 254 note 2 Delcor, op. cit. p. 112: ‘II faut croire que nous avons là (i.e. 8), et surtout ligne 12, un jeu de mot intraduisible entre bkwr, “premier-né”, et bkwr, “dans la fournaise”.’

page 254 note 3 Op. cit. II, 74.

page 254 note 4 NTS, III (1956), 25.Google Scholar

page 255 note 1 We hope that we have already shown enough instances where the vocabulary of the figurative section of the poem looks ahead to the realistic section for our statement that the usage of kwr in 8, 10, 12 can only be appreciated by relating it to the upheavals in 13 ff. to be granted a certain antecedent probability.

page 255 note 2 We grant that the aptness of this metaphor is more evident when the cosmic upheaval is described as a gigantic conflagration, as in iii. 29 ff., than here, where it is conceived as a deluge.

page 255 note 3 The Massoretic vocalization is intended merely to show the basis for our translation and represents no taking of a position with regard to the question of whether this vocalization actually corresponds to the historical pronunciation of Hebrew at the time that our psalm was composed. Since the Hebrew word-play throughout the psalm is untranslatable, we have given in each case the meaning most directly suggested by the context.

page 255 note 4 As Holm-Neilsen remarks, ‘Verbal sentences which use the perfect and the imperfect without any clear logic are thrown together with participle constructions and nominal sentences without any clear structural connection’ (op. cit. p. 61). The translations are divided in rendering the tense of the verb forms, some using the present and some the past. Since the simile in 7 begins with a clear imperfect (’hyh), and since the psalm, at least in its main emphasis, is concerned with future deliverance (according to the interpretation given above), we have consistently used in our translation the present tense (which can be understood in a future sense) and have vocalized waw with the imperfect as simple waw and not as waw conversivum.

page 255 note 5 Kuhn, op. cit. p. 32 n.: ‘mbkryh ist wahrscheinlich Schreibfehler für mbkyrh.’

page 255 note 6 Although mśbry mwt seems to be the same expression as in 8, the context seems to require a derivation from mśbry mwt, whereas in 8 a derivation from mśbr seemed preferable.

page 256 note 1 See p. 278, note 2.

page 256 note 2 Delcor, op. cit. p. 112: ‘surviennent à la fournaise.’

page 257 note 1 ‘“The Hour of Trial” (Rev. iii. 10)’, JBL, LXXXV (1966), 308–14. The expression ‘the hour of trial’ (ή ⋯ρα τ⋯⋯ πειρασμ⋯) itself has a much closer parallel in Qumran than the Old Testament parallels which we cited in this article (p. 311). In 4Q.pPs 37b4 and 4QFI ii. 1 we find ‘t hm⋅rp.Google Scholar

page 257 note 2 God's intervention on behalf of the woman in labour, which has as its consequence the successful delivery of the child, represents God's intervention in the eschatological distress and the rescue of the believing community. Cf. Maier, op. cit. n, 75–6.

page 258 note 1 Cf. υ⋯πομονς in Apoc. iii. 10 and b⊡wqh in 1H iii. 7.

page 258 note 2 Cf. Apoc. iii. 11, ἔρχομαι ταχ, and 1QH iii. 10, hyḥyśw (cf. Isa. lx. 22): ‘das eilende Kommen der eschatologischen Taten Gottes’ (Maier, op. cit. II, 74).

page 258 note 3 Prov. xvii. 3 (cf. 1QM xvi. 15); Prov. xxvii. 21. The texts cited here and below may, of course, contain more than one nuance of the complex ‘crucible-metaphor’. We merely indicate what seems to be the predominant significance. In some texts the basic meaning is not clear. For example, we understand Prov. xxvii. 21 to mean that praise tests a man in the sense that it shows whether he will allow other people's good opinion of him to ‘go to his head’. But this is not the only possible interpretation.

page 258 note 4 I Pet. iv. 12; 1QS i. I7f., reading with Kuhn (op. cit. p. 143) wm⊡rp nswym; viii. 4.

page 258 note 5 Mal. iii. 2 (cf. I Cor. iii. 13).

page 258 note 6 Isa. i. 25; Jer. vi. 27–30; Zach. xiii. 9; CD xx. 25–7; Luke. xii. 49, 51.

page 258 note 7 Jer. vi. 27–30 LXX; Mai. iii. 3; Sir. ii. 5; Sap. iii. 6; 1QH v. 16; f 18, 4; 1QM xvii. 1, 9.

page 258 note 8 Of the bondage of Egypt: Deut. iv. 20; I Kings viii. 51; Jer. xi. 4.

page 258 note 9 Of the exile: Isa. xlviii. 10.

page 258 note 10 Ezekiel xxii. 18, 20, 22; CD xx. 3.

page 258 note 11 Matt. xiii. 42, 50.

page 258 note 12 1QH i. 22.

page 258 note 13 Brown, art. cit. pp. 311–2.

page 258 note 14 Ibid. p. 314: ‘For Christians this tribulation, besides being a threat to their physical safety, will also be a further test of their faith…’