No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

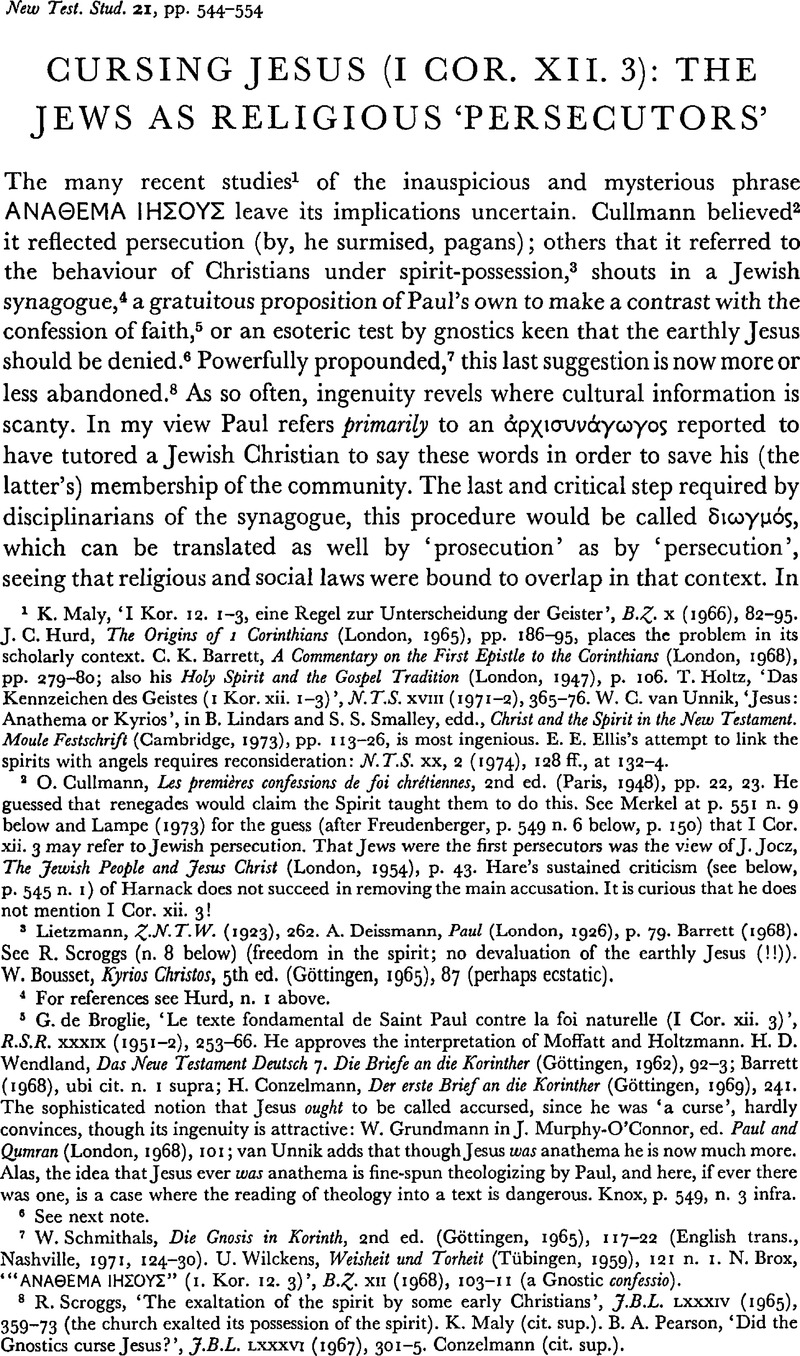

Cursing Jesus (I Cor. xii. 3): The Jews as Religious ‘Persecutors’

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Short studies

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1975

References

page 544 note 1 Maly, K., ‘I Kor. 12. 1–3, eine Regel zur Unterscheidung der Geister’, B.Z. X (1966), 82–95.Google ScholarHurd, J. C., The Origins of 1 Corinthians (London, 1965), pp. 186–95, places the problem in its scholarly context.Google ScholarBarrett, C. K., A Commentary on the First Epistle to the Corinthians (London, 1968), pp. 279–80; also his Holy Spirit and the Gospel Tradition (London, 1947), p. 106.Google ScholarHoltz, T., ‘Das Kennzeichen des Geistes (1 Kor. xii. 1–3)’, N.T.S. XVIII (1971–1972), 365–76.Google Scholarvan Unnik, W. C., ‘Jesus: Anathema or Kyrios’, in Lindars, B. and Smalley, S. S., edd., Christ and the Spirit in the New Testament. Moule Festschrift (Cambridge, 1973), pp. 113–26, is most ingenious.Google ScholarE. E. Ellis's attempt to link the spirits with angels requires reconsideration: N.T.S. XX, 02 (1974), 128 ff., at 132–4.Google Scholar

page 544 note 2 Cullmann, O., Les premières confessions de foi chrétiennes, 2nd ed. (Paris, 1948), pp. 22, 23. He guessed that renegades would claim the Spirit taught them to do this. See Merkel at p. 551 n. 9 below and Lampe (1973) for the guess (after Freudenberger, p. 549 n. 6 below, p. 150) that I Cor. xii. 3 may refer to Jewish persecution.Google Scholar That Jews were the first persecutors was the view of Jocz, J., The Jewish People and Jesus Christ (London, 1954), p. 43. Hare's sustained criticism (see below, p. 545 n. I) of Harnack does not succeed in removing the main accusation. It is curious that he does not mention I Cor. xii. 3!Google Scholar

page 544 note 3 Lietzmann, , Z.N.T.W. (1923), 262.Google ScholarDeissmann, A., Paul (London, 1926), p. 79.Google ScholarBarrett (1968). See R. Scroggs (n. 8 below) (freedom in the spirit; no devaluation of the earthly Jesus (!!)).Google ScholarBousset, W., Kyrios Christos, 5th ed. (Göttingen, 1965), 87 (perhaps ecstatic).Google Scholar

page 544 note 4 For references see Hurd, n. 1 above.

page 544 note 5 de Broglie, G., ‘Le texte fondamental de Saint Paul contre la foi naturelle (I Cor. xii. 3)’, R.S.R. XXXIX (1951–2), 253–66. He approves the interpretation of Moffatt and Holtzmann.Google ScholarWendland, H. D., Das Neue Testament Deutsch 7. Die Briefe an die Korinther (Göttingen, 1962), 92–3;Google ScholarBarrett, (1968), ubi cit. n. 1 supra;Google ScholarConzelmann, H., Der erste Brief an die Korinther (Göttingen, 1969), 241.Google ScholarThe sophisticated notion that Jesus ought to be called accursed, since he was ‘a curse’, hardly convinces, though its ingenuity is attractive: Grundmann, W. in J. Murphy-O’Connor, ed. Paul, and Qumran, (London, 1968), 101; van Unnik adds that though Jesus was anathema he is now much more. Alas, the idea that Jesus ever was anathema is fine-spun theologizing by Paul, and here, if ever there was one, is a case where the reading of theology into a text is dangerous. Knox, p. 549, n. 3 infra.Google Scholar

page 544 note 6 See next note.

page 544 note 7 Schmithals, W., Die Gnosis in Korinth, 2nd ed. (Göttingen, 1965), 117–22 (English trans., Nashville, 1971, 124–30).Google ScholarWilckens, U., Weisheit und Torheit (Tübingen, 1959), 121 n. 1.Google ScholarBrox, N., ‘“ΑΒΑϴΕΜΑ ΙΗΣΟΥΣ” (1. Kor. 12. 3)’, B.Z. XII (1968), 103–11 (a Gnostic confessio).Google Scholar

page 544 note 8 Scroggs, R., ‘The exaltation of the spirit by some early Christians’, J.B.L. LXXXIV (1965), 359–73 (the church exalted its possession of the spirit). K. Maly (cit. sup.).Google ScholarPearson, B. A., ‘Did the Gnostics curse Jesus?’, J.B.L. LXXXVI (1967), 301–5. Conzelmann (cit. sup.).Google Scholar

page 545 note 1 G. W. H. Lampe, ‘Church discipline and the interpretation of the Epistles to the Corinthians (I Cor. 5. 1–6)’, in Farmer, W. R. and others, edd., Christian History and Interpretation: Studies Presented to John Knox (Cambridge, 1967), pp. 337–61.Google ScholarHare, D. R. A., The Theme of Jewish Persecution of Christians in the Gospel according to St Matthew (Cambridge, 1967) strictly disciplines unauthentic claims about Jewish persecution.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

page 545 note 2 Lampe, G. W. H., ‘St Peter's denial’, B.J.R.L. LV, 2 (1973), 346–8.Google Scholar

page 545 note 3 διώκω: Gal. i. 13, 23; Phil. iii. 6 (διώκων); Acts ix. 1–5 (διώκεις), 13, xxii. 7–8, xxvi. II (πολλ⋯κιςτιμωρ⋯ν αὐτοὐς ⋯ ν ⋯γκαονβλααφημεῖν, περιαας τε ⋯μμαιν⋯μενος αὐιοῑς ⋯δτωκον ἔως κα⋯ ε⋯ς τ⋯ς ἔξω π⋯λεις,) 14–15. Oepke, T.W.N.T. 11, 229–30. L.S.J., Lex., s.v. IV, shows that διώκω also means to prosecute as a plaintiff. Hare would write the word down as (merely) ‘harass’, which is whitewashing.

page 545 note 4 διωγμ⋯ς (see also below, n. 6): Mark iv. 17/Matt. xiii. 21 (note Luke's comment: it is a trial, in both senses πειρασμ⋯ς); διωγμο⋯: Mark X. 30; Rom. viii. 35; II Cor. XII. 10; II Thess. i. 4; II Tim. iii. 11. Rom. xii. 14 is interesting as it brings persecution and cursing into juxtaposition.

page 545 note 5 δεδιωγμ⋯νοι Matt. v. 10; διώξοναιν … ἔνεκεν το⋯ (II); v. 44 (διωκ⋯ντων), x. 23. Mark iii 9; (ἔνεκεν ⋯μο⋯)/Luke xxi. 12 (διώψουσιν…ἔνεκεν το⋯ ⋯ν⋯ματι⋯ς μον) Matt, xxiii. 34/Luke xi. 49. John XV. 20, xvi. 2. The best corroboration comes from parallel ideas without the technical vocabulary: persecution begins in the home: Mark xiii. 12–13/Matt. X. 21–2/Luke xxi. 16–17.

page 545 note 6 διωγμ⋯ς: Acts viii. 1. The position is correctly stated at John ix. 22, xii. 42 (see below). In Acts xiii. 50 the word has both spiritual and secular connotations. So John v. 16?

page 545 note 7 As supplied by critical scholars referred to by Hare, op. cit. pp. 19, 85 ff.

page 545 note 8 ⋯δ⋯ωαν ιοὑς προϕ⋯τας τοὺς πρ⋯ ὑν⋯ν (!): Matt. v. 12. προϕ⋯ταις: Luke vi. 23. Matt, xxiii. 34/Luke xi. 49 (on which see Klein, G., ‘Die Verfolgung der Apostel, Luk. 11. 49’, Neues Testament und Geschichte … Oscar Cullmann zum 70. Geburtstag (ZürichTübingen, 1973), pp. 113–24). I Thess. ii. 15–16 is important and difficult: seeGoogle ScholarMichel, O. in Eckert, W. and others, edd., Antijudaismus im Neuen Testament? (Munich, 1967), pp. 50–9;Google ScholarBammel, E., ‘Judenverfolgung und Naherwartung’, Z.T.K. LVI (1959), 294–315 (it may not relate to specific past acts, but chiefly dwell on the signs of the End).Google Scholar

page 546 note 1 Juster, J., Les Juifs dans I’Empire Romain. Leurs Conditions juridique, économique et sociale I (Paris, 1914), 233–3.Google ScholarTcherikover, V., Hellenistic Civilization and the Jews (Philadelphia/Jerusalem, 1959) is of great value (see pt. 11, ch. 2).Google Scholar

page 546 note 2 Juster, 1, 354 ff. Tcherikover, pp. 306–8, 325, 332.

page 546 note 3 Juster, 1, 233 n. 1. Referring to Josephus, Ant. XIV. 10. 13–16 Juster explains the need for, and point in, excommunicating Christians. See the behaviour of Samaritans as explained by Josephus, Ant. xi. 8 (341). That the practice of excommunicating ‘idolaters’ existed long before Christ is proved by CD XIX. 34-XX. 13 (Lohse, Die Qumran Texte, 102–5). All the ‘Saints of the Most High’ have cursed (er6rûhû) them.

page 546 note 4 It is not known how many Jews in the diaspora lived in non-Jewish environments, but the orthodox will always have tended to congregate together. Tcherikover, pp. 304–5, 308.

page 546 note 5 Juster, 1, 414–15, 418, 422–4. Josephus’s particulars at Ant. xiv. 115–17 regarding the judicial powers of Jewish communities have been overlooked since Juster. The correct analogy is with the Millet system known in the Ottoman Empire. See Juster, II, 110–12. Gallio (Acts xviii. 15) understood the Jews to have exclusive domestic competence, or so Luke understood this would be believed without doubt.

page 546 note 6 Richardson, P., Israel in the Apostolic Church (Cambridge, 1969). Gal. vi. 16; Rom. ix. 6; Jas. i. I; 1 Pet. i. I, ii. 9; Heb. xiii. 22–4.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

page 547 note 1 Braude, W. G., Jewish Proselyting in the First Five Centuries of the Common Era (Providence, 1940).Google ScholarBamberger, B.J., Proselytism in the Talmudic Period (Cincinnati, 1939).Google Scholar

page 547 note 2 A recent decision of the Orissa High Court (India) holds, after lengthy examination of the Bible and ‘Vatican II’ that Christians have the right, under Art. 25 of the Constitution, to propagate their religion, provided they did not interfere with public order, morality or health, and a local statute, passed in order to prosecute/persecute Christians, was struck down as ultra vires. The modern Gallio is obliged to accept jurisdiction in the ‘secular state’.

page 547 note 3 Juster, 1, 233. Jos. Ant. XIX. 5. 2, 3 (190); Con. Ap. 11. 237. On the delicacy of Jewish-pagan relations see van Unnik, W. C., ‘Die Anklagen gegen die Apostel in Philippi’, Mullus. Fests. Th. Klauser (Jahrb. Ant. Christ., Ergänzungsbd. 1) (Münster/W., 1964), pp. 366–73.Google ScholarFrend, W. H. C., Martyrdom and Persecution in the Early Church (Oxford, 1965), ch. 3.Google Scholar

page 547 note 4 Juster, 1, 343. Philo, Leg. 45. Cullmann, ubi cit., 21.

page 547 note 5 See e.g. Deut. xvii. 11–13, xviii. 20.

page 548 note 1 Correctly Rom. i. 23, 25; Col. iii. 5; cf. Gal. v. 20; I Cor. v. 11, vi. 9. Davies, W. D., Paul and Rabbinic Judaism (London, 1948), pp. 29–30. ‘Idol’ means ‘false god’: I John v. 21.Google Scholar

page 548 note 2 Paul applied anathema himself: I Cor. v. 2, 4–5, 13. For CD xix. 34–xx. 13 see p. 546 n. 3 above. Simeon b. Sheạtaạh; (1st cent. B.C.) threatened ạHoni with niddwy (Mishnah, Taanit, III. 8).

page 548 note 3 ⋯ϕορ⋯αωαιν (Mark vi. 22), ⋯κβ⋯λωαιν (ibid.), John xii. 42 (οὐχὡμολ⋯γουν), xvi. 2. All instances of ⋯κβ⋯λλειν may be scrutinized to see whether they covertly allude to excommunication: Matt. viii. 12, xxi. 39, xxii. 13, xxv. 30? Hare would interpret the word as ‘social ostracism’, but could this be effected without an institutional act, seeing that to separate oneself from a ‘brother’ was socially and religiously objectionable?

page 548 note 4 makkat mardût. Matt. x. 17, xx. 19, xxiii. 34; Acts v. 40–1; II Cor. xi. 24. Hare's scepticism of this penalty is traceable to his reluctance to admit exclusive competence in the synagogue with reference to moral offences. The NT sources are here corroborated by later, but culturally continuous information. Epiphanius, Haer. xxx. 11 (PG 41. 423). Maimonides (p. 551 n. 9 inf.), VII. 1 (stripes are usually more appropriate than excommunication). Juster, 11, 161. Chajes, Z. H., Student's Guide (London, 1952), p. 35.Google Scholar

page 548 note 5 I Cor. i. 23, ii. 2. To preach Jesus as Lord was attributed to apostles in Palestine also: Acts ii. 36, x 36.

page 548 note 6 Justin, I. Apol. 31.6. Hare makes political aspects more significant than religious aspects here: true, but we are interested in the formula at I Cor. xii. 3.

page 548 note 7 Dial. 117 (see next note).

page 549 note 1 Dial. 17. 1, 108. 2. These may be taken as typical. There is no need to hesitate to date the practice back to Paul's time since Paul himself was sent as an envoy κα⋯ τοῑς ἔξω!

page 549 note 2 Derrett, , Law in the New Testament (London, 1970), pp. 424–5, 453–5. Hare avoids considering the effects of Jesus’s own utterance before the meeting.Google ScholarO’Neill, J. C., ‘The charge of blasphemy at Jesus's trial before the Sanhedrin’, in Bammel, E., ed., The Trial of Jesus (London, 1970), pp. 72–7 ignores Jesus's provocative words. What I Tim. i. 19–20 means is not clear, but their ‘blasphemy’ of something or someone (Paul himself?) made him curse or excommunicate them.Google Scholar

page 549 note 3 Gal. iii. 13.1 should unhesitatingly link Deut. xxi. 23 with Lev. xxiv. 16 since Josephus does so: Ant. iv. 202. See 4QpNah. 7 f. (Jeremias, G., Der Lehrer der Gerechtigkeit, Göttingen, 1963, pp. 134–5). The notion that the curse undergone by Jesus terminated the curse at Deut. xxvii. 26 and enabled believers to revert to the promise made to Abraham is explained byGoogle ScholarKnox, W. L., St Paul and the Church of Jerusalem (Cambridge, 1925), p. 230 n. 19.Google Scholar

page 549 note 4 For ⋯ναθεματ⋯ω see C.I.Att., App. (I.G. III. 2), pp. xiii f., Wünsch, R., Antike Fluchtafeln, Kl.T. XX (1912), no. 1 (p. 5 nn.).Google ScholarDeissmann, G. A., Light from the Ancient East (London, 1927), p. 95. Juster, ii, 159–60.Google ScholarMichel, Ch., ‘Anathème’, D.A.C. I, 1926–1940. Behm, T.W.N.T. I, 354–5. On its figuring (as in the Birkat-ha-Minim) as a liturgical factorGoogle Scholar (Bornkamm, G., Early Christian Experience, London, 1969, pp. 169–70) I feel bound to reserve doubts.Google Scholar

page 549 note 5 Jastrow, Diet., 1591–2.

page 549 note 6 Pliny, Epp. 10. 96 (maledicerent Christo, Christo maledixerunt). Ayerst, D. and Fisher, A. S. T., edd., Records of Christianity, I (Oxford, 1971) 14–16.Google ScholarSherwin-White, A. N., The Letters of Pliny (Oxford, 1966), pp. 691–710, esp. 700–1. The same, ‘Early persecutions and Roman law again’, J.T.S. in, 2 (1952), 199 ff. Mr Sherwin-White informs me (16 July 1973) that there was no Roman persecution of Christians anywhere (so far as we know) during the period when I Corinthians must have been written.Google Scholarde Ste-Croix, G. E. M., ‘Why were the Early Christians persecuted?’, Past & Present 26 (1963), 6.CrossRefGoogle ScholarFreudenberger, P., Das Verhalten der römischen Behörden gegen die Christen (Munich, 1967).Google Scholar

page 550 note 1 Does ⋯ποατοσατ⋯ʓω at Luke xi. 53 recall the process of putting to a suspect a formula which he must accept or reject? The verb normally means to teach to repeat by word of mouth: Plato, Ethyd. 276c, 277a, and therefore to correct mistakes in repetition, tutoring. ⋯ποατομ⋯ʓω means ‘know by heart’, ‘be word-perfect’: Or., sel. in Jes. (6. 26) (PG 12. 824B).

page 550 note 2 Lampe (1967), 355.

page 550 note 3 Mishnah, Avot n. 5(4).

page 550 note 4 And therefore valued (Acts viii. 20). There need be no doubt but that they believed that the Spirit was conferred in baptism (Matt. iii. 16, cf. Acts viii. 16–17): Wikenhauser, A., Pauline Mysticism (Freiburg/Edinburgh, 1956), p. 119, refers to I Cor. vi. 11, xii. 13.Google Scholar

page 550 note 5 See references at Vermes, G., Jesus the Jew (London, 1973), p. 91 n. 30. Hence the widespread concern about false prophets: citations at Lampe (1967), p. 361, also G. W. H. Lampe, ‘Grievous wolves’, Christ and the Spirit (above, p. 544 n. 1), pp. 253–68. On the significance of the coming of the Spirit as anticipation of the End seeGoogle ScholarCaird, G. B., The Apostolic Age (London, 1955/1966), p. 58. On blasphemy of the Spirit as suggesting ‘false prophet’/‘deceiver’/μ⋯γος see the rich material atGoogle ScholarBerger, K., ‘Die königlichen Messias-Traditionen des N.T.’, N.T.S. XX, 1 (1973), at p. 10 n. 38. I set store by Acts iii. 25: ὐμεῑς ⋯στε ο࿀ ν࿀ο⋯ τ⋯ν προϕητ⋯ν.Google Scholar

page 551 note 1 Mark xiii. 11–12/Matt. x. 17–20/Luke xii. 11–12, xxi. 14–15. Schulz, S., Q, (Zurich, 1972), pp. 442–4. See John xiv. 26. The procedure is actually illustrated at I Cor. ii. 3–5!Google Scholar

page 551 note 2 Lampe (cited p. 545 n. 5 above), p. 355.

page 551 note 3 Lev. x. 3; Ezek. xxviii. 22; Hag. i. 8; Isa. xlix. 3 (‘Thou art my servant, Israel, in whom I will be glorified’).

page 551 note 4 Matt. v. 16, xv. 31; Luke xxiii. 47; John xii. 28, xiv. 13, xv. 8, xvii. 1, 4; Rom. xv. 9; Gal. i. 24; II Thess. i. 12; I Pet. iv. 11.

page 551 note 5 Lampe (1967), p. 355. The technical words are ⋯μολογ⋯ω, μαρτυρ⋯ω or, on the contrary, ⋯ρνεῖσϴαι. See II Mace. vi. 6.Google Scholar

page 551 note 6 I Tim. vi. 13. The ‘confession’ = ‘not denying’ image is to be found passim in our texts, e.g. Johni. 20; Rom. x. 9. The Jews denied Christ before Pilate: Acts iii. 13 (Cullmann, ubi cit., pp. 20–1). On the theme see K. Berger, cit. sup., p. 550 n. 5, at pp. 18–20. See Rev. iii. 8–9 (trial at ν. 10!).

page 551 note 7 I Cor. xvi. 22; Gal. i. 8; Rom. ix. 3; I Cor. v. 11.

page 551 note 8 G. W. H. Lampe, ‘St Peter's denial’ (cit. sup.).

page 551 note 9 Presumably saying' ārûr: CD xx. 8; b. Shev. 36 a (Judg. v. 23). Maimonides, Mishneh Torah I, Study of Torah, 6, 4 (b. M. Q,. 17a, Soncino trans, p. 106; j. M. Q,. in. 81 a, b). The synagogue formula will have been ‘J. meharam’ (he has been accursed/excommunicated).Arm, M., Histoire de I’excommunication Juive (Nîmes, 1882). Jesus is alleged to have been put under a ban (b. Sanh. 107b), but this is irrelevant even if it reflects post-A.D. 135 practice.Google ScholarSchlatter, A., Paulus, 3rd ed. (Stuttgart, 1962), p. 333.Google ScholarLampe, (1967), p. 357. H. Merkel, ‘Peter's curse’, in E. Bammel, ed., The Trial of Jesus (cit. sup.), pp. 66–71 (rightly connecting οὐκ οιδα τ⋯ν ανθρωπον [cf. Matt. xxv. 12; Luke xiii. 25, 27!?] with ostracism, see b. M. Q. 16a).Google Scholar

page 552 note 1 Matt. xii. 31–2 conflates two versions of this promise. Lampe, , B.J.R.L. LV (1973), 357. The passage is not dealt with in detail by Hare. R. Schippers proposes to reconstruct an Aramaic original (a single sentence) rendered differently by Ur-Markus’s source and by Q,; he approves the Q, version, but finds the contrast between the Son of Man and the Holy Spirit intelligible only after Easter: ‘De Zoon des Mensen in Mt. 12, 32-Lk. 12, 10, vergeleken met Mk. 3, 38’ in Ex Auditu Verbi, Berkouwer Festschrift (Kampen, 1965), pp. 233–57, summarized at ‘The Son of Man in Matt, xii. 32 = Lk. xii. 10…’, inGoogle ScholarCross, F. L., ed., Studia Evangelica iv (Berlin, 1968), 231–5.Google Scholar

page 553 note 1 See L.S.J., Lex., ⋯π⋯γω 2: ‘to bring before a magistrate and accuse’. Dem. 22. 27. Matt. xxvi. 57; Luke xxi. 12; Acts xxiii. 17, xxiv. 7 (TR); Dan. iv. 22 (LXX).

page 553 note 2 ii. 18–20. For a most important close discussion of the Qumran text in comparison with the MT see Brownlee (below).

page 553 note 3 Hence the passive in ἤγεσϴε. Would John vi. 44 be relevant?

page 553 note 4 Brownlee, W. H., The Text of Habakkuk in the Ancient Commentary from Qumran (Philadelphia, Soc. Bibl. Lit., 1959), pp. 81–7 proves how little substantial deviation from the MT need be feared when reconstructing a midrash of Paul’s type.Google Scholar

page 553 note 5 For a translation see Dupont-Sommer, A., The Essene Writings from Qumran (Oxford, 1961), pp. 267–8.Google Scholar

page 553 note 6 I Cor. iii. 16–17, vi. 19; cf. II Cor. vi. 16 (….nothing to do with idols).

page 553 note 7 b. Sanh. 7 b, Soncino trans. 29.

page 553 note 8 The Jews themselves were a mere ethnos before Yahweh chose them, and they are an ethnos still in terms of the Roman privileges and their own self-image. The Corinthians included Jewish Christians (I Cor. vii. 18).

page 553 note 9 άφωνος means (if capable of uttering non-meaningful sounds, as at Sapph. 118; II Pet. ii. 16; Isa. liii. 7 LXX; Philo, Vita Mos. 1. 83) incapable of communicating (I Cor. xiv. 10). Thus the word is very appropriate in a discussion which will cover spirit-possession and glossolalia.

page 553 note 10 λαλεῑν is the technical word for prophetic speech! Jaschke, H., λαλεῑν bei Lukas’, B.Z. XV, 1 (1971), 109–14.Google Scholar

page 554 note 1 ‘Confession’ primarily, and only secondarily ‘invocation’ (Hahn, F., Christologische Hoheitstitel, Göttingen, 1963, p. 119) orGoogle Scholar‘acclamation’ Kramer, W., Christos Kyrios Gottessohn, Zurich, 1963, pp. 61, 165.Google ScholarOn the importance of κ⋯ριος ᾽׀ησο⋯ς see also Moule, C. F. D. at J. T. S. X (1959), 261–2, andGoogle ScholarSchweizer, E., Ev. Theol. XVII (1957), 12.Google ScholarLongenecker, R. N., The Christology of Early Jewish Christianity (London, 1970), pp. 125, 127.Google Scholar