No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

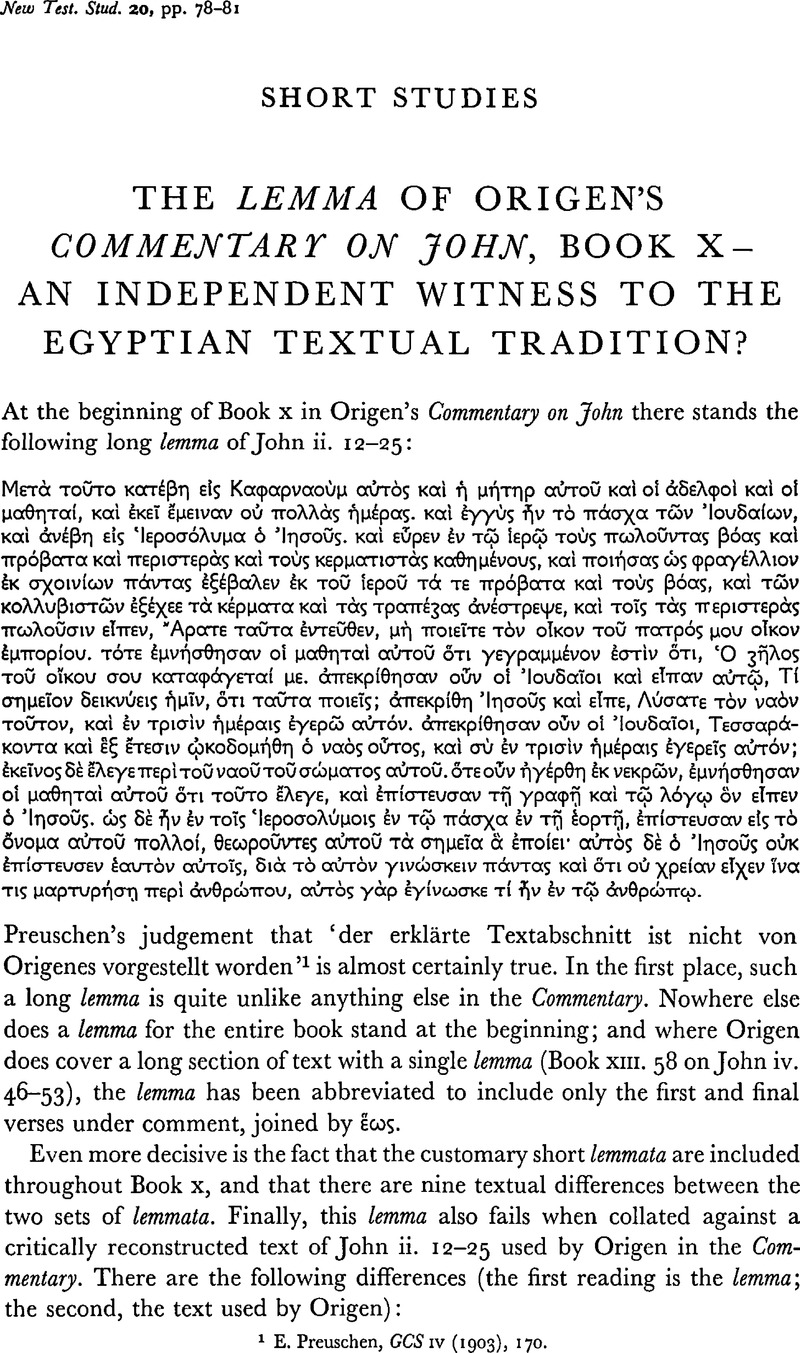

page 78 note 1 Preuschen, E., GCS IV (1903), 170.Google Scholar

page 79 note 1 Although άνέστρεψε occurs in two citations of this passage (the lemma in Book x. 20 and a long citation of vv. 14–16 in Book XIII. 56), it seems quite clear that these reflect scribal errors. For in five adaptations of this verse, four of which occur in the commentary ad loc., the verb appears in inflected forms and always as a form of άναγρέπω (Jo. x. 23 άνατρέπεσθαι; idem άνατρέπει; Jo. x. 25 άνατρεπομένας; Jo. x 45 άνατετραϕέναι; Jo. XIII. 56 άνάτετράϕθαι).

page 79 note 2 Op. cit. p. 170.

page 79 note 3 Biblica, LII (1971), 357–94.Google Scholar

page 81 note 1 It should perhaps be noted further that the existence of such a text in Caesarea may be related to the coming of Origen to that city in 231. But the question remains problematic.

page 81 note 2 First, the MSS of this tradition exhibit no tendencies to group into a text type, either with a high percentage of agrcement over large blocks of text or with a large number of variants peculiar to these MSS against the rest. See conclusions about John xi in Colwell, E. C. and Tune, E. W., ‘The Quantitative Relationships between Ms test-types’, Biblical and Patristic Studies in Memory of Robert Pierce Casey (Freiburg, 1963), pp. 28–9Google Scholar; and about John iv in my study in Biblica (the folding chart, facing p. 366).

Second, the key Church Fathers, who have been shown to support such MSS in Mark or Matthew (Origen and Eusebius), show no such proclivities in the Gospel of John. For Origen see my study in Biblica; for Eusebius see Suggs, M. J., ‘Eusebius’ Text of John in the “Writings Against Marcellus”’, J.B.L. LXXV (1956), 137–42.Google Scholar