Introduction

The synthetic biology revolution

Synthetic biology is the application of engineering principles to design and construct new biologic entities.[Reference Cheng and Lu1] Drawing from disciplines including molecular and systems biology, synthetic biology is set to revolutionize how we utilize biology, just as chemical synthesis transformed chemistry, and the integrated circuit transformed computing. Specifically, synthetic biology allows biologic systems to be engineered for manufacturing chemicals, foods, or fabricating materials, producing healthcare products, processing information, and producing energy.[Reference Maynard2–Reference Currin, Swainston, Day and Kell6]

One of the most prominent examples of synthetic biology is the production of the anti-malaria drug artemisinin through an engineered yeast host.[Reference Ro, Paradise, Quellet, Fisher, Newman, Ndungu, Ho, Eachus, Ham, Kirby, Chang, Withers, Shiba, Sarpong and Keasling7] Other healthcare examples include the accelerated production of vaccines,[Reference Dormitzer, Oldstone and Compans8] or mining biosynthetic gene clusters for novel antibiotic production.[Reference Smanski, Zhou, Claesen, Shen, Fischbach and Voigt5] Synthetic biology has also catalyzed exciting developments for the production of sustainable food alternatives, including the production of grapefruit flavoring nootkatone,[Reference Fraatz, Berger and Zorn9] yeast-produced milk or egg substitutes, and laboratory-grown meat.[Reference Kadim, Mahgoub, Baqir, Faye and Purchas10,Reference Check Hayden11] The production of many commodity chemicals has also been demonstrated,[Reference Cameron, Bashor and Collins3,Reference Li and Borodina12] some of which are entering commercial scale production, moving us away from reliance on petrochemical sources.[Reference Jullesson, David, Pfleger and Nielsen13,Reference Carothers, Goler and Keasling14] Recently, significant funding has also been raised by a number of synthetic biology companies seeking to produce novel materials at commercial scale.[Reference Service15,Reference Flores Bueso and Tangney16]

The rapidly falling costs for both DNA sequencing and DNA synthesis, a trend often referred to as the Carlson curve,[Reference Carlson17] have stimulated progress in synthetic biology.[Reference Hughes and Ellington4] This has led to phenomenal growth in available DNA sequence data,[Reference Yin, Lan, Tan, Lu, Vasilakos and Liu18] providing inspiration for “biobricks” which can be cheaply synthesized for recombinant expression. Furthermore, developments in DNA assembly techniques, the characterization and standardization of DNA parts, and the implementation of engineering design–build–test cycles into automated work flows is revolutionizing our ability to engineer biology for our own ends.[Reference Maynard2–Reference Currin, Swainston, Day and Kell6]

Synthetic biology for the fabrication of novel materials

In essence, nature is a molecular assembler. It is a nanotechnology which we are able to control through synthetic biology techniques, allowing us to access nature's hard-won advanced materials, and to even engineer them toward our own needs and applications.

In the context of material fabrication, it is helpful to categorize materials derived through synthetic biology into two classes: direct and indirect materials. Direct synthetic biologic materials include structural proteins and carbohydrates, such as spider silk, cellulose, and collagen. These are structural materials produced by cells. Indirect synthetic biologic materials, on the other hand, include the production of material precursors (such as monomeric small molecules for polymer or adhesive production) through engineered enzymes. Prominent examples of each are presented in this review.

Biologic systems achieve impressive feats of materials engineering through near-flawless control over the synthesis and assembly of the constituent parts, primarily proteins. From a materials science perspective, proteins can be considered highly multifunctional polyamide hetero-polymers with unparalleled complexity compared with synthetic analogs. Moreover, proteins can offer perfect mono-dispersity and can self-assemble through protein folding to attain complete control over microstructure, which in turn governs macroscopic mechanical properties. Custom-designed, recombinant proteins can now be produced relatively easily in biological host organisms (as well as cell-free systems) through the tools of synthetic biology.

The direct biomanufacturing of monomers and other compounds from engineered organisms is another way in which synthetic biology could contribute to the next generation of materials. Within cells, cascades of enzyme-catalyzed chemical reactions occur to produce all manner of biologically derived molecules.[Reference Smanski, Zhou, Claesen, Shen, Fischbach and Voigt5] By engineering cells to express a multitude of bespoke enzymes, tailored molecules––including the monomers to advanced polymeric materials––can be produced. Furthermore, synthetic biology offers us the potential to reach a novel chemical space, inaccessible through traditional methods.[Reference Smanski, Zhou, Claesen, Shen, Fischbach and Voigt5,Reference Friedman and Ellington19,Reference Cheallaigh, Mansell, Toogood, Tait, Lygidakis, Scrutton and Gardiner20]

Finally, whilst the synthetic chemist is highly dependent on petroleum-derived feedstocks, solvents, and relatively harsh, energy-intensive processing conditions, the synthetic biologist by definition employs benign conditions (conditions that are compatible with life) and renewable, naturally-occurring feedstocks and nutrients as precursors. The natural world has produced an array of materials with outstanding strength, toughness, resilience, and optical properties, despite being hugely constrained by processing conditions (ambient temperature and pressure, and minimal pH swings), limited access to raw materials and comparatively few building blocks (20 amino acids and 32 glycans, compared to the vast number of possible building blocks of synthetic chemistry).[Reference Dimarco and Heilshorn21,Reference Demirel, Cetinkaya, Pena-Francesch and Jung22]

The synthetic biology toolkit

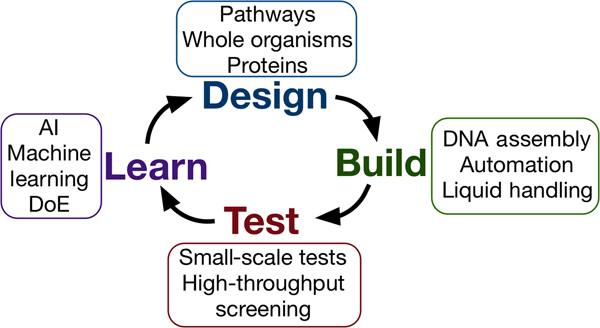

Synthetic biologists have a growing repertoire of tools and methods at their disposal for the direct and indirect production of synthetic biological materials.[Reference Maynard2–Reference Smanski, Zhou, Claesen, Shen, Fischbach and Voigt5] The decrease in DNA sequencing costs provides biologists with a rapidly expanding set of natural templates for the production of a diverse range of biomaterials. For example, reading the genome of a spider allows the genes which code for spider silk proteins to be identified, copied, and engineered to be expressed in organisms that are much easier to propagate, such as bacteria, as shown in Fig. 1(a).

Figure 1. (a) A schematic representation detailing the steps in taking a material in nature, such as spider silk, and producing it in a heterologous host. Sequences coding for genes of interest (e.g., a spider silk protein), can be sequenced (DNA reading) and chemically synthesized (DNA writing). The synthesized DNA (red) is then typically incorporated into an expression vector (depicted by the circles) which is transformed into a host organism (e.g., Escherichia coli), for protein expression. In the example shown, spider silk proteins are then spun into fibers, and collected on a roller (material fabrication). (b) Assembly of DNA parts (A to E) allows the construction of protein chimeras, or the construction of metabolic pathways combining enzymes from multiple sources for monomer production.

However, and very importantly, the decreasing cost and enhanced power of DNA synthesis, editing and assembly methods, mean that synthetic biologists are not limited to molecular building blocks that are found in nature. They can synthesize new DNA sequences, allowing them to design novel proteins, specified precisely down to the amino acid level.[Reference Butterfoss and Kuhlman23] A key advantage of this bioengineering approach is the fact that rapid optimization of functional proteins and biopolymers can be achieved through several rounds of random DNA mutagenesis, informed by sequence–activity relationships, followed by rapid screening and selection of desirable properties.[Reference Currin, Swainston, Day and Kell6] Furthermore, protein domains, or enzymes in metabolic pathways, can be assembled in innovative combinations, for the production of protein chimeras or unique pathways toward desired metabolic products, as shown in Fig. 1(b). Increasingly predictive computational tools ensure that the initial designs are reliably translated into engineered organisms.[Reference Cheng and Lu1] The scale and ambition of these biologic engineering projects have increased by several orders of magnitude in the last years, with the refactoring and de novo synthesis of entire microbial genomes now realistically within reach.[Reference Hutchison, Chuang, Noskov, Assad-Garcia, Deerinck, Ellisman, Gill, Kannan, Karas, Ma, Pelletier, Qi, Richter, Strychalski, Sun, Suzuki, Tsvetanova, Wise, Smith, Glass, Merryman, Gibson and Venter24] A number of reviews offer a more detailed overview of synthetic biology techniques and recent developments.[Reference Maynard2–Reference Currin, Swainston, Day and Kell6]

Challenges for applying synthetic biology in the production of materials

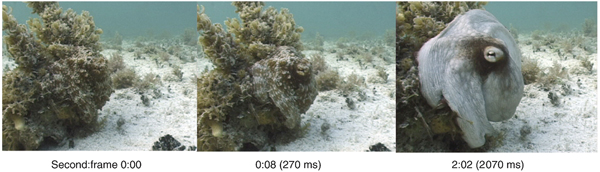

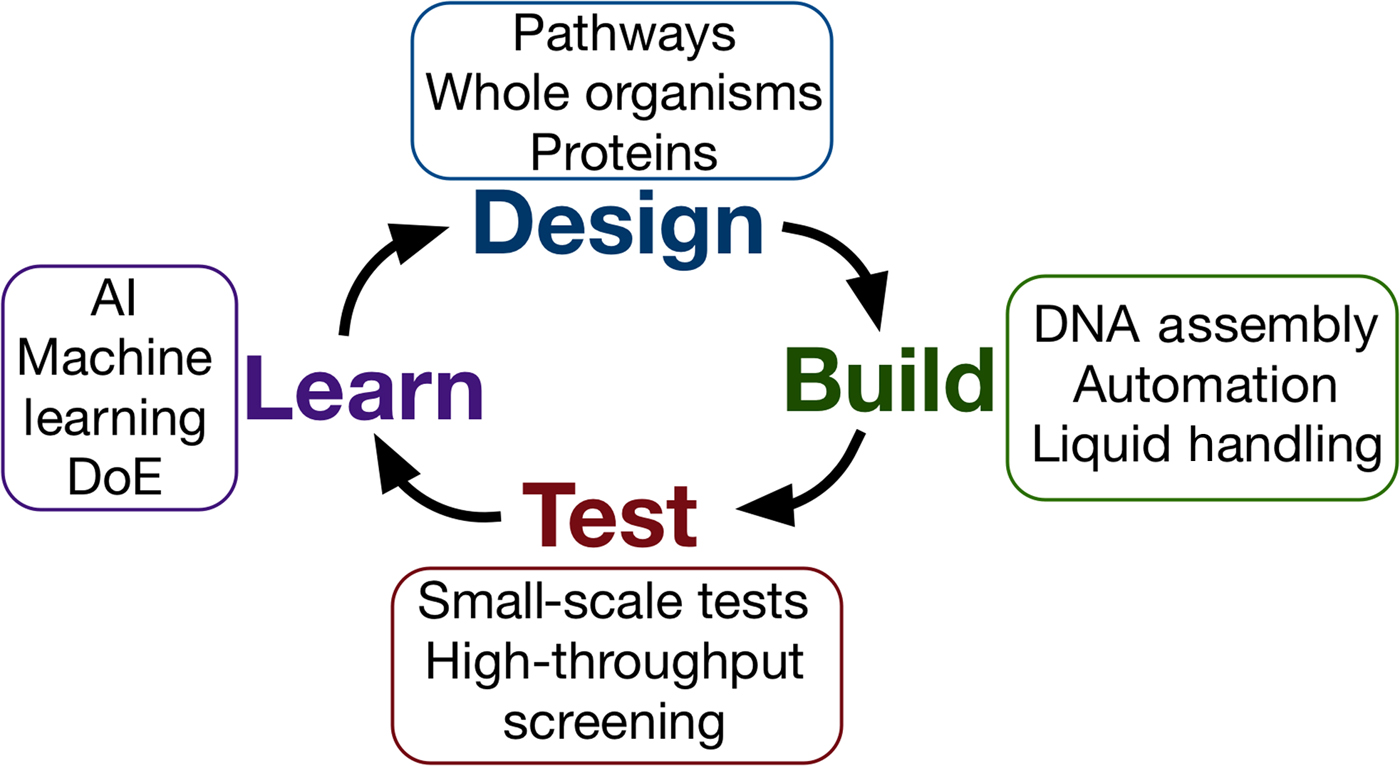

Synthetic biology seeks to apply the engineering design–build–test cycle to biology, testing many samples in parallel and iterating over a number of cycles to find an optimum solution (Fig. 2). Automation, liquid handling robots, and high-throughput screening are currently being employed in established synthetic biology areas, to allow large numbers of designs to be built and tested quickly and efficiently.[Reference Currin, Swainston, Day and Kell6] Crucially, this approach requires the “test” to be executed on a small scale, for example, in a 96- or 384-well plate format, somewhat at odds with traditional material testing approaches.[Reference Dowling, Siva Prasad and Narayanasamy25] The large data-sets this approach provides can be used to feed machine learning algorithms or empirical models, which can in turn be used to inform the next round of designs. One route toward applying this methodology may be the use of “surrogate” factors, which correlate with a desired property but are more easily measured in a high-throughput setting.[Reference Le Feuvre and Scrutton26] A small number of promising leads might then be selected from a pool of hundreds of thousands, for more traditional, larger-scale material tests.

Figure 2. The design–build–test–learn cycle for engineering biology. Iterating around the design–build–test cycle, testing large numbers of samples parallel, allows the synthetic biologist to efficiently find an optimum solution to their biology engineering problem.

Synthetic biology for advanced materials in protection and aerospace

Whilst the focus of research into synthetic biological materials has primarily been on biomedical materials (materials designed to interact with biologic tissue) for applications such as regenerative medicine, the delivery of therapeutic agents, and other “soft” material applications,[Reference Dimarco and Heilshorn21,Reference Bryksin, Brown, Baksh, Finn and Barker27–Reference Banta, Wheeldon and Blenner29] there exists great potential for synthetic biology to deliver the next generation of advanced materials for everyday use, such as (bio)polymers, fibers, optical materials, and adhesives.[Reference Le Feuvre and Scrutton26]

Although the long-term target for many novel technologies is the mass market, high initial costs often limit the first wave of novel materials to premium products and sectors with large spending budgets. For this reason, the scope of this review focuses on applications within the protection and aerospace sectors, as these sectors are more likely to take up novel technologies for advanced applications before economies of scale reduce costs and open up other markets.

In this review, an overview of the application of synthetic biology in some key areas applicable to protective materials and aerospace is given, discussing fibers, adhesives, and active camouflage materials. The most prominent examples of each are highlighted, along with their underlying bio-physical/bio-chemical mechanisms, followed by a discussion of recent studies on the application of synthetic biology to reproduce such materials.

Finally, the challenges and opportunities for the application of synthetic biology for the next generation of advanced materials are highlighted, as well as a prospective outlook for the future direction of research in this emerging and dynamic landscape.

Synthetic biology for fibers, adhesives, and active camouflage materials

Advanced materials such as high-performance fibers, adhesives, and dynamic camouflage coatings are actively being pursued for application in next-generation hardware in the protection and aerospace sectors. Materials produced through synthetic biology have great promise in this regard, as well as offering a route to sustainable and distributed production. Although there are numerous examples of such materials that are actively being researched, such as high-toughness and self-healing squid ring teeth proteins,[Reference Pena-Francesch, Akgun, Miserez, Zhu, Gao and Demirel30] and highly resilient insect resilin,[Reference Elvin, Carr, Huson, Maxwell, Pearson, Vuocolo, Liyou, Wong, Merritt and Dixon31] here we focus only on selected illustrative examples, which have been studied most extensively.

Synthetic spider silk for protective clothing and apparel

Silk is most commonly associated with textiles produced from fibers unraveled from cocoons spun by the silkworm Bombyx mori.[Reference Vollrath and Porter32,Reference Sutherland, Young, Weisman, Hayashi and Merritt33] This luxury fabric has been used by humans for thousands of years due to its attractive properties including soft touch, appearance, and durability.[Reference Koeppel and Holland34] Silks have also been used in armors throughout history. For example, the Mongolian heavy cavalry would wear silk shirts under their armor to act as a cushion for arrows that punctured the skin. The silk shirt would not be punctured, but instead the silk fibers get twisted around the arrowhead as it entered the skin, allowing it to be removed more safely.[Reference Turnbull and Reynolds35] Silk was also used to make bullet proof vests around the beginning of the 20th century, with one gifted to the Archduke Ferdinand.[Reference Łotysz36] Finally, silk was recently identified as a useful material for fragment protection via heavy-silk underwear by the US and UK military.[Reference Lewis, Pigott, Randall and Hepper37]

Silkworms are not the only organisms to produce silks; they are also produced by thousands of arthropod species, with every silk evolved for a specific task.[Reference Vollrath and Porter32,Reference Sutherland, Young, Weisman, Hayashi and Merritt33] Orb web weaving spiders for instance can produce up to seven different types of silks, each with a specialized function and some with attractive mechanical properties.[Reference Craig38,Reference Brunetta and Craig39] These silks are defined by the gland in which they are produced: major ampullate, minor ampullate, tubiliform, flagelliform, aggregate, pyriform, and aciniform.[Reference Rising and Johansson40] Major ampullate (dragline) silk has evolved to act as a safety line for spiders, requiring it to be both strong (tensile strength of 1150 MPa) and tough (214.5 MJ/m3),[Reference Vollrath, Madsen and Shao41] outperforming many industrial fibers.[Reference De Araújo42,Reference Gosline, Guerette, Ortlepp and Savage43] For this reason, spider dragline silk has received much attention as a potential material for apparel and armor applications.[Reference Service15] In comparison, silkworm silk possesses a strength of only ~360 MPa and a toughness of ~50.5 MJ/m3.[Reference Mortimer, Guan, Holland, Porter and Vollrath44] Given the use of silkworm silk in modern infantry armor already,[Reference Lewis, Pigott, Randall and Hepper37] the use of stronger and tougher spider silk could allow a reduction in weight and more comprehensive use.

Spider silk proteins

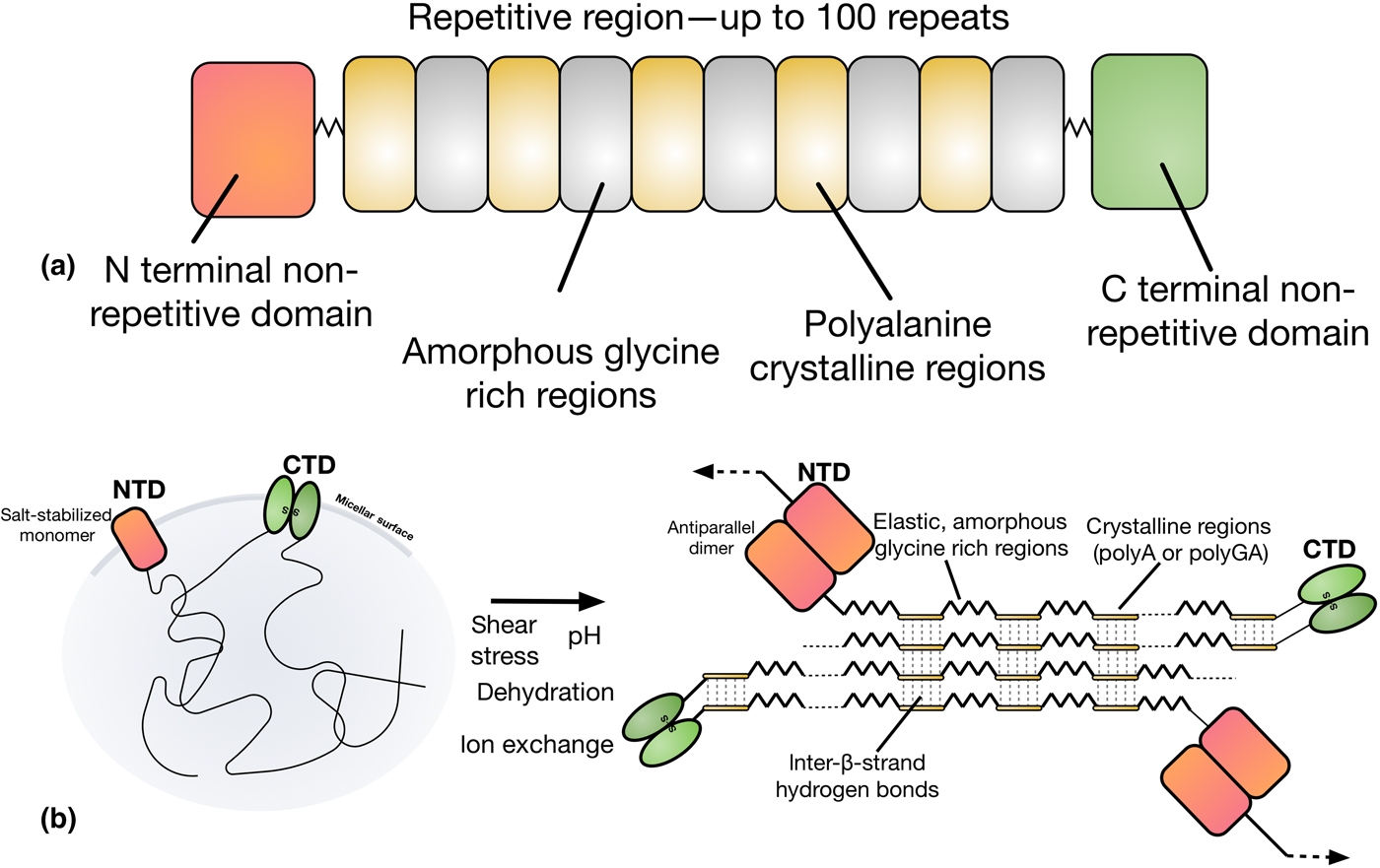

Natural dragline spider silk proteins (spidroins) are typically 200–350 kDa in size, and consist of three distinct regions, as depicted in Fig. 3.[Reference Rising and Johansson40,Reference Hagn, Thamm, Scheibel and Kessler45] The bulk of the spidroins are highly repetitive, with a block copolymer-like arrangement of polyalanine regions and glycerine-rich regions.[Reference Tokareva, Jacobsen, Buehler, Wong and Kaplan46] The strength of spider silk is thought to be the product of these polyalanine regions, which stack into β-sheet nanocrystals in the silk fiber.[Reference Keten, Xu, Ihle and Buehler47] These nanocrystals are embedded in an amorphous matrix made up of the glycine-rich regions, which grants spider silk its elasticity and flexibility.[Reference Keten, Xu, Ihle and Buehler47] The N and C terminals of the spidroins are highly conserved, non-repetitive globular domains which each form five-helix bundles.[Reference Andersson, Chen, Otikovs, Landreh, Nordling, Kronqvist, Westermark, Jörnvall, Knight, Ridderstråle, Holm, Meng, Jaudzems, Chesler, Johansson and Rising48] The terminal domains have been shown to play a crucial role in allowing spidroins to be stored at high concentrations (30–50% w/v) in the ampulla, and in initiating fiber assembly.[Reference Heidebrecht, Eisoldt, Diehl, Schmidt, Geffers, Lang and Scheibel49]

Figure 3. (a) The domain structure of spider silk proteins, consisting of non-repetitive N- and C-terminal domains, flanking a much larger repetitive section which alternates between glycine-rich regions and polyalanines. (b) A model for the conversion of soluble spidroins, stored as protein micelles, into insoluble silk fibers through the assembly triggers of sheer stress, changing pH, dehydration, and changing salts in the silk gland of a spider. Adapted from Ref. [Reference Hagn, Thamm, Scheibel and Kessler45].

Spiders employ a number of assembly triggers for spinning

Upon spinning, spidroins proceed through a long and narrowing S-shaped spinning duct. This duct is hypothesized to act like a hollow fiber dialysis membrane for the dehydration of the spinning dope, with the narrowing generating shear stress.[Reference Rising and Johansson40] This is simultaneously accompanied by the replacement of chaotropic sodium and chloride ions with potassium and kosmotropic phosphate ions, inducing salting out of the spidroins.[Reference Humenik, Smith, Arndt and Scheibel50,Reference Eisoldt, Hardy, Heim and Scheibel51] The pH in the ampullate gland drops from 7.6 in the tail, to at least 5.7 by halfway through the spinning duct, as a result of the action of carbonic anhydrase.[Reference Andersson, Chen, Otikovs, Landreh, Nordling, Kronqvist, Westermark, Jörnvall, Knight, Ridderstråle, Holm, Meng, Jaudzems, Chesler, Johansson and Rising48] This drop in pH has two important effects on the N and C terminal domains which act as regulatory elements that control spidroin solubility and assembly,[Reference Rising and Johansson40] referred to as the lock and the trigger and depicted in Fig. 3(b).[Reference Andersson, Jia, Abella, Lee, Landreh, Purhonen, Hebert, Tenje, Robinson, Meng, Plaza, Johansson and Rising52] The N-terminal domain (the lock), dimerizes as pH decreases.[Reference Hagn, Thamm, Scheibel and Kessler45,Reference Jaudzems, Askarieh, Landreh, Nordling, Hedhammar, Jörnvall, Rising, Knight and Johansson53] Because the C-terminal domain forms a constitutive disulphide-linked homodimer,[Reference Gauthier, Leclerc, Lefèvre, Gagné and Auger54] this dimerization by the N-terminal domain locks the spidroins into an infinite network. In contrast, the C-terminal domain (the trigger) partially unfolds in response to decreasing pH, becoming less stable.[Reference Hagn, Eisoldt, Hardy, Vendrely, Coles, Scheibel and Kessler55] The C-terminal domain contains a sequence prone to hydrophobic β-aggregation, and the unfolding mediated by decreasing pH in combination with changes in salts and sheer stress causes the C-terminal domain to form β-sheet amyloid-like fibrils. This structural conversion is thought to act as a seed for the transition of the repetitive region into a β-sheet conformation, analogous to the nucleation phenomenon seen in amyloid fibril formation.[Reference Gauthier, Leclerc, Lefèvre, Gagné and Auger54]

In the ampulla, the highly concentrated spinning dope has been suggested to have lyotropic crystal behavior.[Reference Heim, Keerl and Scheibel56] The coordinated action of acidification, ion exchange, dehydration, and shear stress generated by a narrowing of the duct is proposed to cause assembly into a nematic phase, allowing the correct alignment of β-sheet nanocrystals as the fibers are formed.[Reference Heidebrecht, Eisoldt, Diehl, Schmidt, Geffers, Lang and Scheibel49,Reference Braun and Viney57] In the production of some man-made fibers such as Kevlar®, alignment of crystalline regions is also important in achieving high-strength fibers.[Reference Chatzi and Koenig58]

Industrial spider silk production through synthetic biology

While spider silks have attractive mechanical properties, spiders cannot be efficiently farmed for their silks.[Reference Koeppel and Holland34] Unlike silkworms, which produce all of their silk during one moment in life (pupation), spiders produce lower quantities of silk throughout their entire lives. Furthermore, spiders are usually aggressive and cannibalistic, making the gathering of many spiders in a single location challenging.[Reference Omenetto and Kaplan59] Despite these difficulties, limited attempts have been made to produce spider silk textiles from spiders.[Reference Lewis60] Recently a full-sized spider silk textile was produced as an artistic endeavor, at a cost of one million reeled spiders and approximately 280 person years of work, as recently reviewed.[Reference Koeppel and Holland34] Clearly, in order to harness this material, an alternative, more efficient production method is necessary.

The production of recombinant spidroins using synthetic biology offers a route to spider silk without spiders. Furthermore, synthetic biology allows amino acid control over the spidroins that are produced, with the potential to tune the primary sequence of the spidroin toward desirable mechanical properties. A range of production methods has been investigated,[Reference Tokareva, Michalczechen-Lacerda, Rech and Kaplan61] including from the milk of transgenic goats or mice,[Reference Hinman, Jones and Lewis62,Reference Xu, Fan, Yu, Huang, Zhao, Lian, Dai, Wang, Liu, Fei and Li63] production in bacteria or yeast,[Reference Widmaier, Tullman-Ercek, Mirsky, Hill, Govindarajan, Minshull and Voigt64,Reference Vendrely and Scheibel65] plants,[Reference Hauptmann, Weichert, Menzel, Knoch, Paege, Scheller, Spohn, Conrad and Gils66,Reference Scheller and Conrad67] and transgenic silk worms.[Reference Wen, Lan, Zhang, Zhao, Wang, Kajiura and Nakagaki68–Reference Ji, Niu, Yu, Huang, Dong, Li, Chen, Xu and Tan70]

Recombinant spidroin production is only the first step, however. Spidroins must be purified, processed to a suitable concentration, and spun into fibers using one of many possible spinning techniques. Various spinning methodologies have been investigated including wet spinning, dry spinning, electrospinning, straining flow spinning, and the use of microfluidics, as detailed in a recent, comprehensive review.[Reference Koeppel and Holland34] Both the spidroin that is produced and the method employed to spin it influence the mechanical properties of the resulting fiber. Furthermore, many fibers see large improvements in mechanical properties through the use of post-spin drawing, resulting in thinner fibers with a more aligned microstructure.[Reference Koeppel and Holland34] For these reasons, synthetic spider silk production is both a synthetic biology and materials science challenge, requiring input from both disciplines.

In addition to numerous academic efforts to produce synthetic spider silk, in recent years, a number of commercial entities have received large amounts of funding with the aim of producing synthetic spider silk for a variety of applications. These include Bolt Threads, Spiber Inc, Spiber Technologies AB, AMSilk and Kraig Biolabs.[Reference Service15]

Typically, the recombinant spidroins produced have been smaller “mini-spidroins”, with a repetitive region smaller than that is found in native spidroins. As the size of the repetitive region expressed increases, spidroin yields have been shown to decrease,[Reference Xia, Qian, Ki, Park, Kaplan and Lee71] making larger recombinant spidroins difficult to work with. The repetitive region consists predominantly of alanine and glycine residues, the codons for which are GGX and GCX, respectively.[Reference Tokareva, Michalczechen-Lacerda, Rech and Kaplan61] This results in DNA sequences which have a high GC content. In addition to this, the repetitive nature of these sequences risks the formation of translation inhibiting secondary structures in the mRNA.[Reference Xia, Qian, Ki, Park, Kaplan and Lee71] Finally, given the extensive use of alanine and glycine in spidroins, it is possible that the availability of these amino acids is limiting in spidroin expression. Indeed the epithelial cells of the spidroin-producing glands have been shown to possess large alanyl- and -glycyl-tRNA pools.[Reference Candelas, Arroyo, Carrasco and Dompenciel72] Efforts to elevate the Escherichia coli glycyl-tRNA pool to improve the expression of larger mini-spidroins granted some success, although with yields still lower than the smaller counterparts.[Reference Xia, Qian, Ki, Park, Kaplan and Lee71]

Matching the mechanical properties of natural spider silk

Unfortunately, many of the efforts to produce synthetic spider silk have resulted in fibers which do not match the mechanical properties of natural spider silk. A number of arguments have been put forward as to why this may be.

Firstly, “mini-spidroins” that are considerably smaller than the native spidroins have usually been produced. Additionally, the terminal domains are often omitted, argued to result in spinning dopes unlike those found in spiders.[Reference Rising and Johansson40,Reference Andersson, Jia, Abella, Lee, Landreh, Purhonen, Hebert, Tenje, Robinson, Meng, Plaza, Johansson and Rising52] Increasing the size of mini-spidroins featuring only the repetitive region has been shown to result in stronger and tougher fibers, although this increase is not linear.[Reference Rising and Johansson40,Reference Xia, Qian, Ki, Park, Kaplan and Lee71] The toughness of structurally-similar squid ring teeth proteins has also been shown to increase with a greater number of tandem repeats in the repetitive region, being attributed to network tie-chain density.[Reference Jung, Pena-Francesch, Saadat, Sebastian, Kim, Hamilton, Albert, Allen and Demirel73,Reference Pena-Francesch, Jung, Segad, Colby, Allen and Demirel74] However, a study employing a spider silk protein with terminal domains showed no increase in strength or toughness when the repetitive region was doubled in size from 48 to 95 kDa, confusing this issue.[Reference Heidebrecht, Eisoldt, Diehl, Schmidt, Geffers, Lang and Scheibel49]

Secondly, that the spinning techniques employed are not truly biomimetic, so do not assemble spidroins in the same way that spiders do, resulting in inferior fibers.[Reference Rising and Johansson40] Recent work showed biomimetic spinning of a small mini-spidroin featuring both terminal domains using a coagulation bath at pH 5.0, triggering conformational changes in the terminal domains and fiber formation. The fibers produced showed to date the best as-spun mechanical properties of any synthetic spider silk, although still inferior to natural spider silk.[Reference Andersson, Jia, Abella, Lee, Landreh, Purhonen, Hebert, Tenje, Robinson, Meng, Plaza, Johansson and Rising52] However, post-stretching did not appear to improve the fibers to the extent seen in other cases.[Reference Heidebrecht, Eisoldt, Diehl, Schmidt, Geffers, Lang and Scheibel49,Reference Rising, Johansson and Andersson75] Importantly, the small size of the mini-spidroins used in this work allowed its concentration using centrifugal concentrators rather than through the use of denaturing conditions, allowing the terminal domains to remain correctly folded and functional throughout the purification process.[Reference Andersson, Jia, Abella, Lee, Landreh, Purhonen, Hebert, Tenje, Robinson, Meng, Plaza, Johansson and Rising52] Recent advances in biomimetic spinning methods may lead to further improvements in biosynthetic silk properties.[Reference Magaz, Roberts, Faraji, Nascimento, Medeiros, Zhang, Greenhalgh, Mautner, Li and Blaker76]

A third important observation is that a small fiber diameter is important for the production of strong fibers, with strength correlating strongly with √(modulus/diameter).[Reference Porter, Guan and Vollrath77] The majority of synthetic spider silk fibers have much larger diameters than natural spider silk, likely contributing to their poorer mechanical properties.[Reference Koeppel and Holland34] However, synthetic silk fibers follow a lower-sloped trend line for generic energy release compared with natural fibers, indicating the presence of more disordered regions.[Reference Koeppel and Holland34] This further emphasizes a need for improved spinning techniques and/or recombinant spidroins which more closely resemble native spidroins.

Recently, a large spidroin featuring only a repetitive region of 557 kDa was produced as a recombinant protein in E. coli.[Reference Bowen, Dai, Sargent, Bai, Ladiwala, Feng, Huang, Kaplan, Galazka and Zhang78] The initial production of two smaller spidroins, subsequently joined together through the use of inteins, was necessary to produce this exceptionally large spidroin. The resulting fiber matched the mechanical properties of natural spider dragline silk for the first time. Crucially, post-spin drawing by 600% of the original fiber length was necessary, resulting in thin (5.7–6.3 µm), highly aligned fibers similar to native spider silk fibers.[Reference Bowen, Dai, Sargent, Bai, Ladiwala, Feng, Huang, Kaplan, Galazka and Zhang78]

Matching the mechanical properties of natural spider silk is an important first step; however, this must be followed by improvements in yield for the industrial production of fibers matching natural spider silk to become a reality.[Reference Bowen, Dai, Sargent, Bai, Ladiwala, Feng, Huang, Kaplan, Galazka and Zhang78] Spiders utilize spidroin terminal domains to effectively polymerize their spidroins upon spinning.[Reference Andersson, Jia, Abella, Lee, Landreh, Purhonen, Hebert, Tenje, Robinson, Meng, Plaza, Johansson and Rising52] Possibly medium-sized mini-spidroins incorporating correctly folded terminal domains which are spun via biomimetic spinning may offer a middle ground between the very large, low-yield spidroins and smaller, higher production-yield, yet mechanically poorer spidroins.

The production of synthetic spider silk is a popular example of the potential for using synthetic biology for the production of new materials. However, synthetic biology must be combined with expertise in mechanical and polymer sciences in order to achieve the goal of sustainable, low-cost production of spider silk with desired mechanical properties. Finally, synthetic biology also offers us the power to produce spidroins not seen in nature, optimized, or evolved toward our needs and applications, rather than to those of spiders.

Synthetic biologic adhesives

Naturally occurring biological materials such as collagen, albumin, and starch were commonly used as glues prior to the development of synthetic adhesives.[Reference Fay79] These glues, which were extracted from various animal and plant products, were used due to their wide availability, facile processability, and versatility.

Many organisms produce their own specialized adhesives for a variety of purposes, such as surface colonization; egg, larval, or pupal attachment; prey capture; locomotion; and defense against predation.[Reference Smith80] Many of these specialized biological adhesives have remarkable properties that are difficult to replicate through synthetic chemical means, such as strong underwater adhesion, exceptional resilience, biocompatibility, adhesion to both polar and non-polar surfaces, as well as intrinsic surface-cleaning mechanisms.[Reference Smith80] Extraction and utilization of such biological adhesives from their natural source are not considered viable however, due to the relatively small quantities produced by individual organisms, as well and difficulties in extraction and purification of the complex, often irreversibly crosslinked, adhesive mixtures.[Reference Hwang, Yoo, Jun, Moon and Cha81]

These issues can now be overcome, however, using the toolkit of the synthetic biologist. As was discussed in section ‘The synthetic biology toolkit’ and depicted in Fig. 1(a), relatively simple (and low cost) tools can be used to directly extract mRNA from organisms corresponding to the adhesive protein(s) of interest, reverse-translate it, and insert the resulting cDNA into a viable plasmid and host organism for recombinant production. This process means that even minute quantities of the rarest adhesive protein can be produced and investigated on gram scales at the laboratory level, as well as countless variants thereafter modified through gene editing for instance.

To date, the primary focus of recombinantly produced biologic adhesives has been for biomedical applications, where biocompatible and water-tolerant adhesives could revolutionize wound treatment, tissue regeneration, and therapeutic compound delivery.[Reference Strausberg and Link82,Reference Lee, Messersmith, Israelachvili and Waite83] Many other uses outside of biomedical science can also be envisioned; however, the ability of many biological adhesives to strongly adhere to both non-polar organic and polar inorganic surfaces, even in the presence of water, solvated ions, oils, and biofilms, could make them ideal for “dirty” environments such as battlefields, disaster zones, or at sea. Durable adhesives with exceptional strength and toughness are also being sought in the aerospace and defense sectors, to join diverse and dissimilar materials such as metals, polymer composites, glasses, and ceramics.[Reference Molitor, Barron and Young84] Ballistic glass, for instance, is a lamellar glass–polymer–ceramic composite which would benefit from stronger, tougher transparent interlayer adhesives to prevent delamination and distribute force upon ballistic impact.[Reference Klement, Rolc, Mikulikova and Krestan85]

Although the physical, chemical, and biological mechanisms of adhesion of a variety of organisms have been investigated, the most well-characterized mechanism to date is that of mussel adhesive proteins (MAPs).[Reference Smith80] Since the utilization of synthetic biology to produce biological adhesives depends on a detailed understanding of the underlying mechanisms involved, MAPs currently provide the best guidance for the synthetic biologists and materials scientists.[Reference Smith80,Reference Lee, Messersmith, Israelachvili and Waite83,Reference Waite, Andersen, Jewhurst and Sun86,Reference Kord Forooshani and Lee87]

Interfacial adhesion mechanisms of MAPs

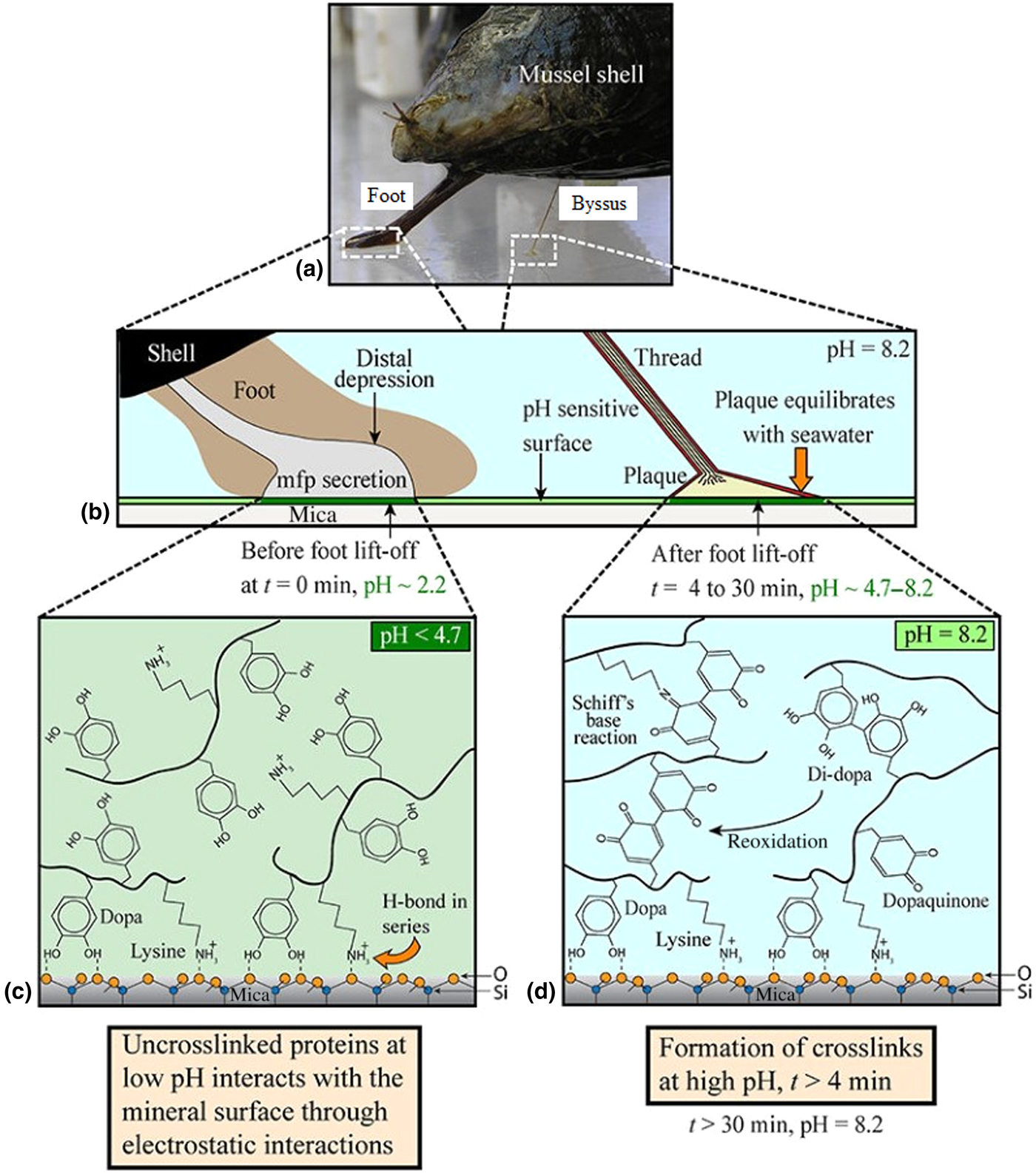

The common marine mussel Mytilus edulis forms strong adhesive bonds to a diverse range of surfaces, allowing colonization of rough, wave-swept intertidal zones. This attachment is achieved through a proteinaceous byssus—a series of threads extending from the foot which terminate in outstretched plaques which form the adhesive interface with the substrata, as shown in Figs. 4(a) and 4(b).[Reference Waite, Andersen, Jewhurst and Sun86,Reference Rodriguez, Das, Kaufman, Israelachvili and Waite88] These plaques are enriched with a variety of MAPs which have been further subdivided into proteins termed Mytilus foot proteins (Mfps), of which there are up to over ten different kinds, five of which are unique to the plaque (Mfps 2–6).[Reference Waite, Andersen, Jewhurst and Sun86]

Figure 4. Mechanism through which mussels adhere to surfaces in seawater. (a) Camera image showing mussel shell, foot, and byssus. (b) Macroscopic changes occurring during adhesive plaque deposition, (c) chemical changes that occur during plaque deposition before, and (d) after equilibration of pH with that of seawater. Reproduced with permission from Rodriguez et al..[Reference Rodriguez, Das, Kaufman, Israelachvili and Waite88]

A common feature of plaque Mfps is a high concentration of the post-translationally modified tyrosine residue 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA), as well as a high proportion of basic amino acids such as lysine. Mfp-3 and Mfp-5 are especially rich in DOPA (20–30 mol%) and are predominantly accumulated at the plaque–substrate interface—indicating the significance of DOPA-rich proteins in the surface bonding mechanism.[Reference Sone and Smith89]

Indeed, various investigations have shown that these DOPA-rich Mfps will not only form extensive hydrogen bonds with polar surfaces, but interactions such as π–π, π–cation, and hydrophobic interactions also allow strong adhesion to non-polar surfaces such as polystyrene and even Teflon®.[Reference Sone and Smith89] At mildly basic pH values, DOPA undergoes a spontaneous redox reaction to form the reactive species dopaquinone, which forms strong complexes with metal ions (e.g., Fe3+, Ca2+, Cu2+, Ti3+, Ti4+, Mn2+, Mn3+, Zn2+) and metal oxide surfaces (e.g., Al2O3, Fe3O4, SiO2, TiO2, and ZnO), respectively, hardening the adhesive and forming strong, yet reversible, bonds to inorganic substrates.[Reference Rodriguez, Das, Kaufman, Israelachvili and Waite88] These metal ion–DOPA chelation complexes have remarkably strong bonds, at approximately 40% the strength of a covalent bond (0.8 versus 2 nN), yet their reversible nature allows for the accommodation of stresses giving exceptional toughness and resilience.[Reference Lee, Scherer and Messersmith90] Removal of metal ions from Mfp-1 resulted in a 50% reduction in hardness, highlighting the importance of metal complexation to the cohesive strength.[Reference Holten-Andersen, Mates, Toprak, Stucky, Zok and Waite91] Dopaquinone also reacts with various nucleophilic functional groups such as −NH2 and −SH, as well as with other DOPA moieties, to form covalently crosslinked networks, further contributing to the hardening of the adhesive and enhancing cohesion.[Reference Liu, Meng, Messersmith, Lee, Dalsin and Smith92]

The oxidation of DOPA to dopaquinone is evidently an important step in the formation and hardening of a strong adhesive bond.[Reference Rodriguez, Das, Kaufman, Israelachvili and Waite88] Since the pH of seawater is slightly basic at 8.2, this oxidation—if not controlled—would occur spontaneously causing the adhesive to cure and harden prematurely. The mussel therefore deposits the MAPs at a significantly lower pH than seawater (<pH 4.7), to prevent premature oxidation of DOPA and allow it and positively charged lysine residues to interact with surface species through H-bonding and electrostatic interactions, as shown in Fig. 4(c).[Reference Rodriguez, Das, Kaufman, Israelachvili and Waite88] Gradual equilibration of the pH with that of seawater then allows spontaneous redox reactions between DOPA and metal oxide surfaces, forming the strong complexation bonds described above and depicted in Fig. 4(d).[Reference Rodriguez, Das, Kaufman, Israelachvili and Waite88] Mfp-6 is understood to facilitate this controlled oxidation; being rich in cystine residues (~11%) in their reduced form, Mfp-6 has been shown to act as an anti-oxidant, recycling dopaquinone back to DOPA to facilitate greater surface complexation.[Reference Kord Forooshani and Lee87,Reference Yu93] The cystine residues in Mfp-6 also crosslink directly with dopaquinone, forming covalent bonds within the adhesive and enhancing cohesion.[Reference Zhao and Waite94]

Other interactions, such as the shielding of DOPA with hydrophobic residues, phosphorene binding to calcareous minerals, displacement of surface-bound water, hydrated ions and oils from substrate surfaces, and other subtle mechanisms such as protein folding dynamics are also understood to play a role in surface adhesion mechanism, but are not as clearly understood as the mechanisms directly involving DOPA.[Reference Waite, Andersen, Jewhurst and Sun86,Reference Kord Forooshani and Lee87,Reference Sone and Smith89,Reference Petrone, Kumar, Sutanto, Patil, Kannan, Palaniappan, Amini, Zappone, Verma and Miserez95] Further elucidation of the complex interactions occurring at the MAP–substrate interface, as well as elucidating other bioadhesive mechanisms, will facilitate the development of both bioinspired and synthetic biologic adhesives for a variety of uses,[Reference Hwang, Zeng, Srivastava, Krogstad, Tirrell, Israelachvili and Waite96] including aerospace and defense. The self-assembled, hierarchically porous microstructure of the plaque likely also plays a critical role in adhesion.[Reference Waite, Andersen, Jewhurst and Sun86]

MAP adhesives through synthetic biology

MAP-inspired synthetic polymers with DOPA or DOPA-like moieties have been produced by chemists and have replicated many properties of biologic adhesives.[Reference Kord Forooshani and Lee87,Reference Ahn, Das, Linstadt, Kaufman, Martinez-Rodriguez, Mirshafian, Kesselman, Talmon, Lipshutz, Israelachvili and Waite97,Reference Westwood, Horton and Wilker98] Naturally occurring MAPs however, having precise control over the local primary peptide sequence surrounding DOPA residues, are still superior adhesives and the synthetic chemist may struggle to attain a similar level of monomer-by-monomer control. Similarly, overcoming the strong dielectric and solvation properties of water at polar interfaces—which frustrates adhesion in wet or high-humidity environments—is a challenging problem for synthetic adhesives, yet biologic systems such as MAPs achieve this with ease. The ability of biological systems to regulate and direct the activity of DOPA, through hydrophobic residue shielding and redox regeneration with protein Mfp-6,[Reference Kord Forooshani and Lee87] is another area where recombinantly produced MAPs could have an advantage over synthetic, biomimetic polymer adhesives.

The use of recombinantly produced MAPs as adhesives was pioneered by Genex Corporation in the late 1980s, who prepared cDNA libraries from M. edulis mRNA and produced MAPs through a yeast expression host.[Reference Maugh, Anderson, Strausberg, Strausberg, McCandliss, Wei and Filpula99,Reference Strausberg, Link, Filpula, Orndorff, Strausberg, McCandliss, Finkelman, Wei, Anderson, Hemingway, Conner and Branham100] Since then, advancements in the techniques and tools of synthetic biology mean MAPs and other biologic adhesives (including mutant variants and chimera proteins) can be produced economically at a large scale and arguably compete with synthetic chemical adhesives in some instances.[Reference Hwang, Yoo, Jun, Moon and Cha81,Reference Hwang, Gim and Cha101–Reference Zhong, Gurry, Cheng, Downey, Deng, Stultz and Lu104]

In 2004, Cha and co-workers isolated the cDNA corresponding to Mytilus galloprovincialis foot protein type 5 (Mgfp-5) and produced significant quantities (40 mg/L of culture) of the recombinant protein in an E. coil host.[Reference Hwang, Yoo, Jun, Moon and Cha81] After tyrosinase treatment to convert tyrosine residues to DOPA, the adhesive properties of the proteins were evaluated on a variety of surfaces, including glass, polystyrene, aluminum, and a commercial silicone-based anti-fouling material. The adhesion, measured through a modified atomic force microscopy (AFM) cantilever-based technique, found a correlation between DOPA content and adhesive performance, but reliable quantification of adhesive strength could not be obtained due to limitations of the measurement technique (probing area could not be accurately determined). Macroscale adhesion tests, which would have allowed direct comparison with commercial adhesives, were not performed, likely due to insufficient quantities of material for such tests. The same group later produced a recombinant type 3 equivalent (Mgfp-3), noting superior production yield and aqueous solubility in comparison to Mgfp-5, however adhesive performance (using the same AFM-based technique) was poorer.[Reference Hwang, Gim and Cha101]

Another interesting study, using both natural and recombinant Mfp-1, was conducted by Zeng et al. who noted the importance of DOPA–Fe3+ bridging complexes in the formation of reversible intramolecular crosslinks.[Reference Zeng, Hwang, Israelachvili and Waite105] Triggered adhesive curing through the addition of multivalent cations, which can be reversed through the addition of the cation-chelating compounds such as EDTA, could pave the way for recombinant biologic “smart” adhesives which could be hardened or softened on requirement.

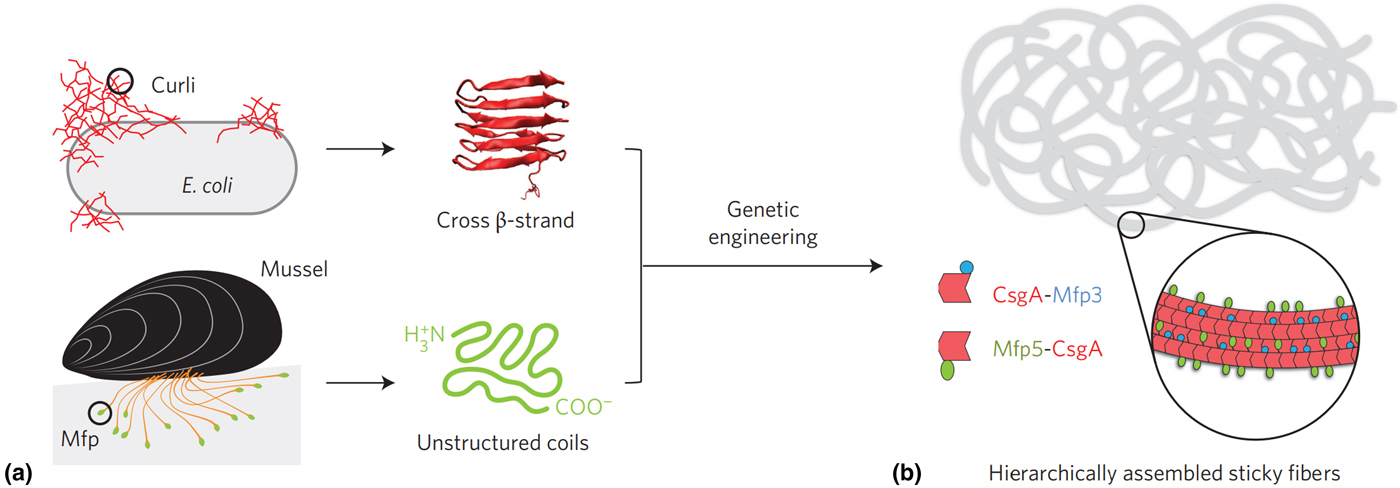

Recently, a recombinantly produced hybrid protein based on Mfp-3 and Mfp-5 with the E. coli amyloid curli protein CsgA was produced by Lu and co-workers and is shown in Fig. 5.[Reference Zhong, Gurry, Cheng, Downey, Deng, Stultz and Lu104] This chimera displayed strong underwater adhesion at 20.9 mJ/m2—which is 1.5 times greater than similar bio-derived protein-based adhesives reported to date, outperforming Mfps and CsgA fibers individually and displaying high tolerance to auto-oxidation under neutral and mildly basic conditions. The authors attributed this performance to the CsgA fibers providing a large surface area for interaction with Mfp domains, in addition to a combination of ionic, cation–π and hydrophobic π–π interactions, depending on the nature of the substrate. Similar chimera proteins assembled could introduce other functionalities, such as RGB sequences to promote cell adhesion,[Reference Hwang, Sim and Cha106] or combining with other mechanically advanced proteins such as spider silk or insect resilin.

Figure 5. (a) Hybrid Mfp-CsgA chimera proteins produced by Yu and co-workers and (b) their self-assembly into adhesive nanofibers. Reprinted with permission from Zhong et al..[Reference Zhong, Gurry, Cheng, Downey, Deng, Stultz and Lu104]

Although adhesives produced through the recombinant synthesis of MAPs, MAP mutants, or MAP chimeras have significant potential for producing a new generation of adhesives with properties unobtainable through synthetic chemical means, there are several challenges and obstacles that still need to be overcome. Current recombinant protein production techniques struggle to produce full-length sequences due to the high M w and repetitive nature of MAP sequences, a problem also seen in the production of recombinant spider silk.[Reference Rising and Johansson40] The high level of post-translational modification of MAP proteins, particularly the conversion of tyrosine to DOPA cannot be achieved in many common hosts such as E. coli, unless a tyrosine oxidizing enzyme such as tyrosinase is produced concurrently, which has yet to be realized.[Reference Strausberg, Link, Filpula, Orndorff, Strausberg, McCandliss, Finkelman, Wei, Anderson, Hemingway, Conner and Branham100]

Although significant research and development is still needed, biologic adhesives have the potential to displace synthetic chemical alternatives as the world gravitates to the post-petroleum era. As technologies such as automation, robotics, high-throughput screening, and machine learning continue to accelerate advances in synthetic biology, similar advances in the characterization and performance evaluation of adhesives will be required for the rapid discovery and optimization of synthetic biologic adhesives with advanced, bespoke properties.

Coatings for signature reduction and active camouflage

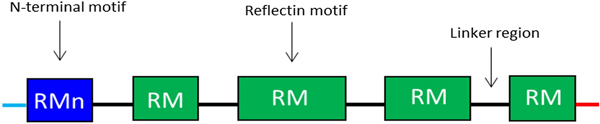

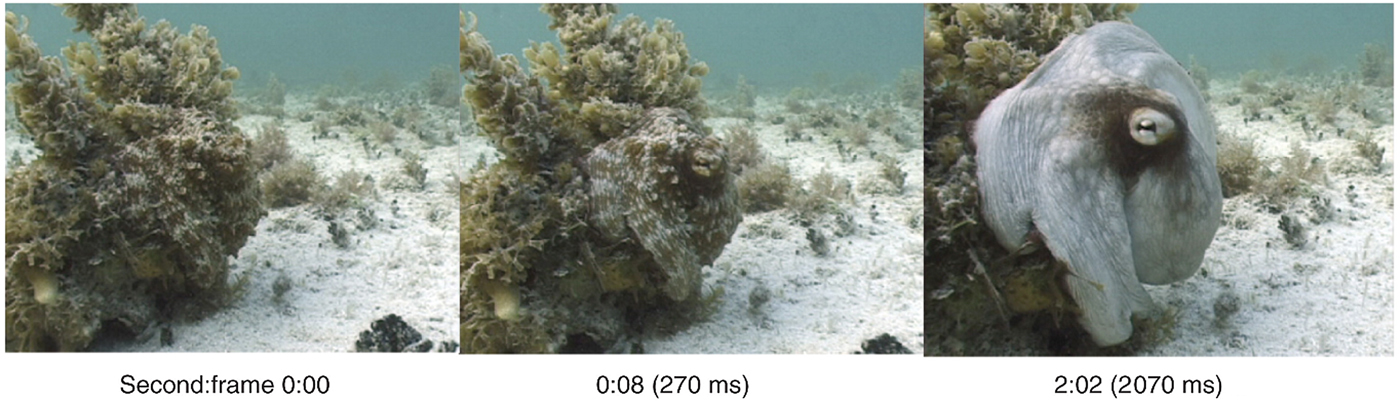

Effective concealment from threats is of paramount importance in the defense and aerospace sectors. The recently deployed F-35 joint-strike fighter reportedly cost over US$40 billion to develop, a large proportion of which went into maintaining a low electromagnetic (EM) signature through carefully angled surfaces and radar-absorbent materials. The next generation of EM signature reduction and management may include active camouflage (which changes and adapts on requirement), a technique already mastered by certain cephalopod species as shown in Fig. 6. This section reviews the mechanisms behind cephalopod dynamic camouflage and reviews recent efforts to replicate these phenomena through synthetic biology.

Figure 6. Adaptive camouflage of the octopus vulgaris: switching from camouflaged to conspicuous in 2 s. Reprinted with permission from Hanlon.[Reference Hanlon112]

Cephalopod coloration

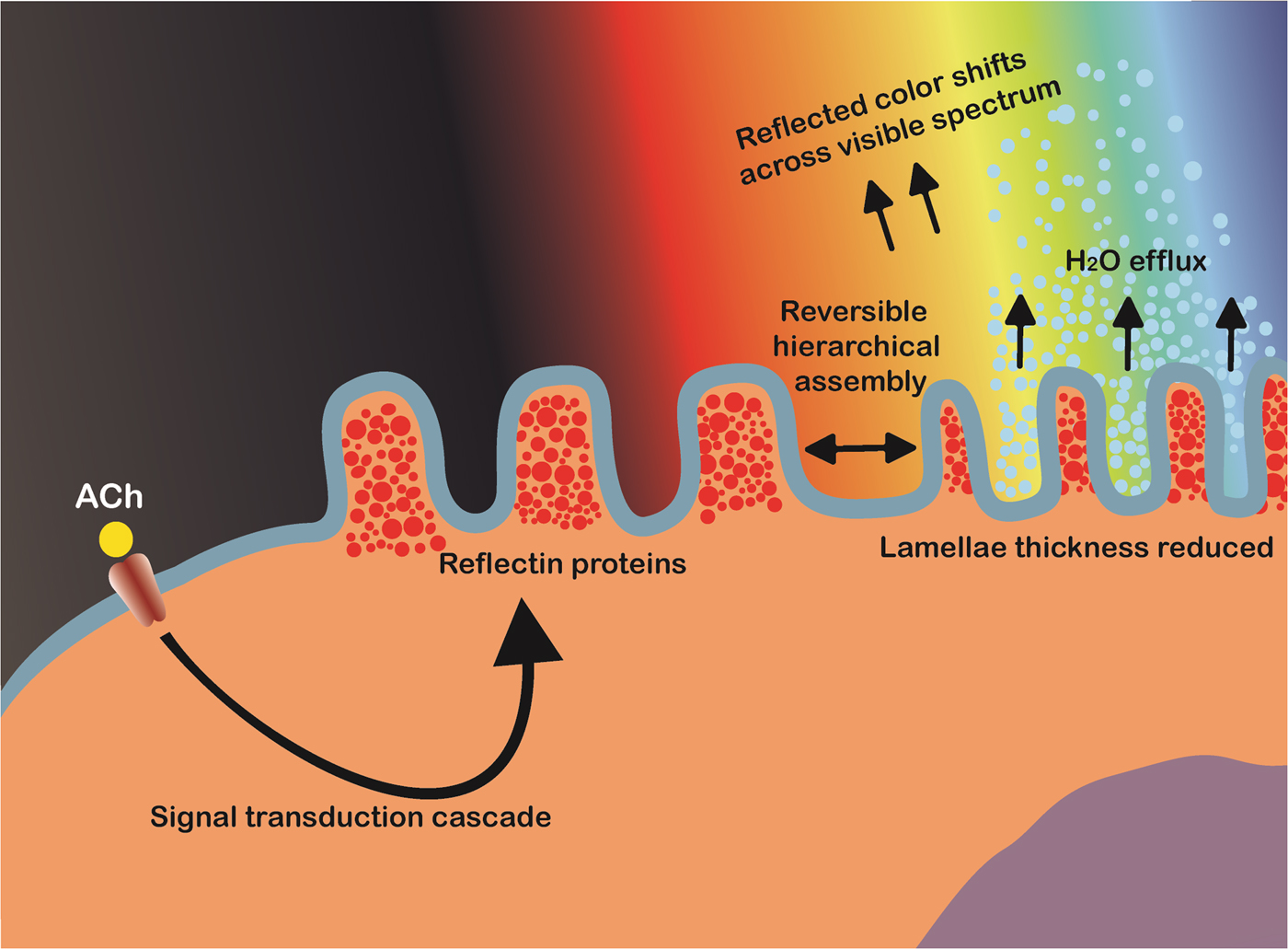

Cephalopods have long been renowned for their ability to rapidly modulate their body coloration to closely resemble their environment, also known as adaptive camouflage and shown in Fig. 6.[Reference Cloney and Brocco107–Reference Hanlon112] These remarkably advanced camouflage traits in species such as the common squid, Lolliguncula brevis, and common cuttlefish, Sepia officinalis, emerge through a combination of layered dermal cells which control the transmission (chromatophores) and reflectance (iridocytes and leucophores) of incident light.[Reference Cooper and Hanlon109,Reference Barbosa, Mathger, Chubb, Florio, Chiao and Hanlon113] Chromatophores, generally found at the outermost layer, are nanostructured pigment-filled cells which act as spectral filters—absorbing, reflecting, and transmitting incident light. Attached to radial muscle fibers which modulate the shape of the cell, cephalopods control the optical properties of chromatophores by contracting/relaxing these fibers, increasing pigment surface area and therefore interaction with light.[Reference Mirow110,Reference Hanlon114,Reference Deravi, Magyar, Sheehy, Bell, Mäthger, Senft, Wardill, Lane, Kuzirian, Hanlon, Hu and Parker115] Leucophores, at the bottom of the layer, are highly reflective broadband light scatterers. Composed of non-absorbing, non-periodic, polydisperse intracellular microparticles, leucophores scatter incident light in all directions (Mei scattering), giving them a diffuse white color and therefore bestowing a convenient white base for overlaying patterns.[Reference Cloney and Brocco107,Reference DeMartini, Ghoshal, Pandolfi, Weaver, Baum and Morse116] Iridophores, often found in between chromatophores and leucophores, are multilayer Bragg reflectors which produce spectral iridescence following their interaction with incident light. Alternating lamellae of high refractive index protein (reflectins) and low refractive index extracellular space are spatially separated by the bilayer membrane, with iridescence defined by coherent Bragg reflection from successive layers and the color defined by the layer thickness and angle of incidence.[Reference Tao, DeMartini, Izumi, Sweeney, Holt and Morse117] This mechanism is modulated by an Acetylcholine (ACh) signal transduction cascade and is depicted schematically in Fig. 7.

Figure 7. Schematic illustration of the proposed bio-mechanical mechanism of iridophore iridescence activation in cephalopods. Acetylcholine (ACh) triggers a signal cascade which leads to the release of protein kinases (tyrosine kinase). The site-specific phosphorylation of tyrosine residues on reflectins triggers reversible hierarchical assembly into a condensed aggregate, accompanied by the efflux of water. This reduces the inter-lamellae thickness of the multilayer Bragg reflectors, changing the wavelengths of light subject to constructive/destructive interference and hence the observed color.

Some cephalopods, such as squid in the Loligidae family, can tightly control the wavelength of light reflected across the entire visible spectrum by rapidly controlling the dimensions of these iridophore Bragg reflectors. Using the neurotransmitter ACh, the reversible site-specific phosphorylation of reflectin tyrosine residues triggers its hierarchical assembly, reducing the occupied volume and hence lamellae thickness. Hierarchical assembly of reflectin results in reduced ion exposure, and is therefore accompanied by platelet dehydration (maintaining electro-osmotic equilibrium and Gibbs–Donnan equilibrium).[Reference Izumi, Sweeney, DeMartini, Weaver, Powers, Tao, Silvas, Kramer, Crookes-Goodson, Mäthger, Naik, Hanlon and Morse118–Reference DeMartini, Krogstad and Morse121] Working in concert, these three mechanisms give cephalopods an extraordinary level of control over their body coloration and patterning, which are believed to be used for both camouflage and communication.[Reference Mirow110,Reference Hanlon, Maxwell, Shashar, Loew and Boyle122] Due to these unique characteristics, cephalopods have become a source of inspiration for the development of novel, dynamic, and optically active biomimetic camouflage, with iridophores in particular, and their primary constituent reflectins, garnering considerable interest in this regard.

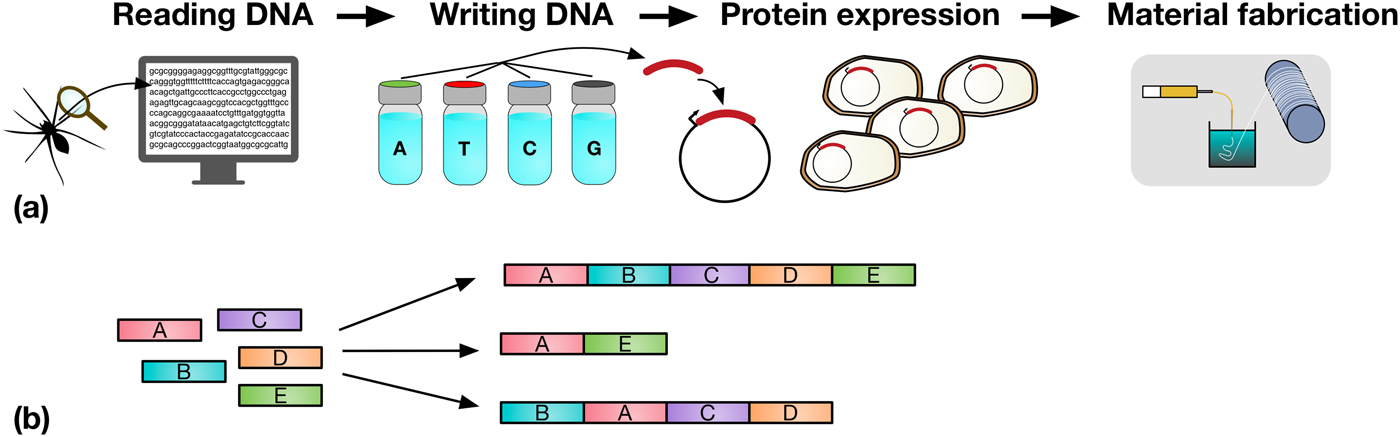

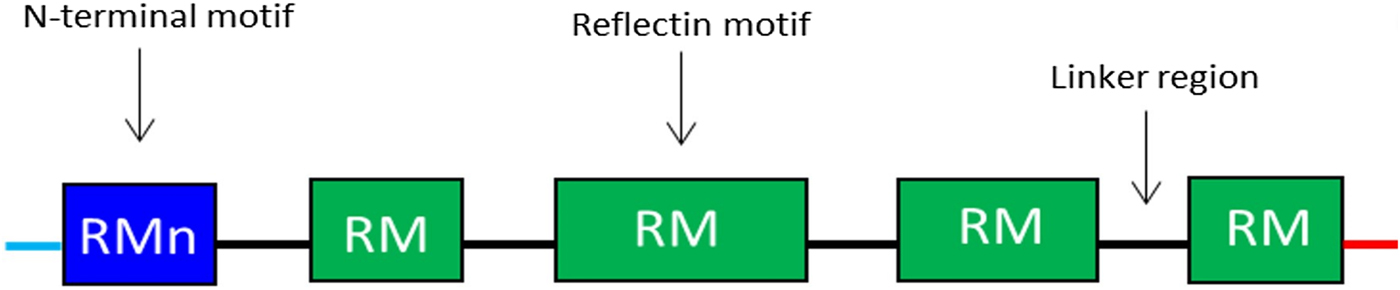

Reflectin structure and function

Reflectins possess a block co-polymeric structure consisting of highly conserved methionine-rich repeating motifs, separated by positively charged polyelectrolyte linker regions, giving reflectins a net positive charge. These repeat motifs, defined as (M/FD(X)5)(MD(X)5)n(MD(X)3/4) and depicted in Fig. 8, exist in two forms—one occurring near the N terminus (the N-terminal motif, RMn) which is highly conserved and found in most reflectin proteins, and another which is distributed throughout the rest of the protein depending on the type of reflectin (the reflectin motif, or RM). Reflectin protein's skewed amino acid sequences underpin their unique assembly properties.[Reference Levenson, DeMartini and Morse119] Upon charge neutralization (in vivo phosphorylation/in vitro pH) the repulsive electrostatic interactions (mainly within linker regions) are overcome by the attractive π–π, sulfur–π, and cation–π interactions, driving hierarchical assembly into condensed secondary structures. Computational structural analysis has revealed differences in the entropic drive to form secondary structures between linkers and motifs. By comparing hydrophobic moment plots, it was found that, when isolated, motifs possessed a high entropic drive to form α-helix and β-sheet secondary structures, with linkers possessing none.[Reference Levenson, DeMartini and Morse119] Introducing linker regions to motifs then decreased the entropic drive for secondary structure formation, suggesting an inhibitory/regulatory role.[Reference Levenson, DeMartini and Morse119] Moreover, the aggregation properties, particularly the homogeneity of particle size upon charge-neutralization driven condensation and hierarchical assembly appear to differ between reflectin isoforms, with those containing fewer reflectin motifs appearing to be less tightly regulated.

Figure 8. Schematic illustration of the general structure of reflectin proteins. Blue region = N-terminal reflectin motif (RMn), green regions = reflectin motif (RM). Flanking linker regions, N and C terminus, colored blue and red, respectively. Conserved region: (M/FD(X)5)(MD(X)5)n(MD(X)3/4).

Understanding the precise roles of reflectin components is crucial to fully explore the limits of reflectin-based camouflage systems. Facilitated by advancements in high-throughput techniques, synthetic biology allows us to dissect the roles of protein constituents down to single amino acids. To investigate the role of the frequency of repeat motifs/linkers, one could envision cloning reflectin isoforms which contain progressively fewer of these regions and comparing, amongst other properties, secondary structure formation, refractive index, and solubility, etc. A similar investigatory method could also be used to examine the role of the size/distribution of motifs and linkers, by cloning isoforms with the desired sequence and comparing their properties. A more thorough appreciation of the role that these regions have on the intrinsic properties of both reflectin proteins and reflectin-based materials could lead to a model with predictive power. This would allow the properties of reflectins, and therefore reflectin-based materials, to be predicted based on the primary sequence, facilitating the design of novel sequences with enhanced properties.

Dynamic and optically active reflectin-based materials inspired by cephalopod iridophores

Since their isolation in 2004,[Reference Crookes, Ding, Huang, Kimbell, Horwitz and HcFall-Ngai123] on the basis that the exogenous application of ACh and calcium ionophores shift the reflectance of mantle iridophores of L. brevis from long wave (red) to short wave (blue),[Reference Cooper and Hanlon109,Reference Mathger124] the material science community began to view reflectins as a structurally adaptive biopolymer that could be exploited. Since then, processing reflectins into optically active materials has been achieved through a variety of techniques and are summarized in Table I. In a seminal paper published in 2007, Naik and co-workers employed a flow-coating technique to deposit a thin layer of recombinant reflectin 1a (Euprymna scolopes) onto highly-reflective silicon substrates, demonstrating, for the first time, the capacity to process these proteins into optically active thin films.[Reference Kramer, Crookes-Goodson and Naik125] After creating gradient films by adjusting the blade tilt (in flow-coating), they noted that the film thickness correlated positively with the wavelength of light reflected, which is expected for structural coloration produced via thin-film interference. They also showed that vapor-induced swelling using water, methanol, or ethanol reversibly shifted reflectance across the visible spectrum (from 400 to 800 nm), causing a red-shift when applied and shifting back when the stimulus was removed. This work ignited interest in reflectin-based dynamic optical materials, and in 2013, Gorodetsky and co-workers expanded on this by exposing reflectin A1 [Loligo (Doryteuthis) pealeii] thin films on graphene-oxide-coated substrates to acetic acid vapors, triggering an increase in thickness due to a combination of vapor-induced swelling and increased interprotein electrostatic repulsion.[Reference Phan, Walkup, Ordinario, Karshalev, Jocson, Burke and Gorodetsky126] Here, the change in thickness (and hence, wavelength shift) was more pronounced than observed with vapor-induced swelling alone, spanning the entire visible spectrum and into the near-infrared (IR); shifting from 600 to 1200 nm. The greater accessible wavelength range, between 400 and 1200 nm (by varying concentration), and an ability to tune reflectivity in situ from the visible to the near-IR region (by 600 nm), coupled with the inexpensive and robust fabrication strategy, made this a decisive step toward reconfigurable biomimetic camouflage technologies for stealth applications. In 2015, the same group demonstrated another method of modulating the thickness (and therefore optical reflectivity) of reflectin thin films on graphene-oxide-coated tape.[Reference Phan, Ordinario, Karshalev, Walkup, Shenk and Gorodetsky127] Using mechanical stretching, the application of uniaxial strain reduced the film thickness by ~25% via the Poisson effect, causing a blue-shift from 980 to 705 nm. The films were then “healed” by annealing with a heat gun, returning to their original proportions and wavelength. The soft, conformable adhesive substrate could be applied to surfaces or objects with a variety of shapes and sizes, meaning it can be suitably applied to an assorted array of defense hardware. One issue with structural coloration as a basis for camouflage technologies is angle-dependent color. In a military setting, there is little benefit to being invisible to your enemy at a precise angle while being visible at most others. The researchers in this case claim to have overcome this concern by producing a material with a broad reflectance peak, seemingly reducing the dependence of viewing angle on color, and therefore on visualization in the IR region.[Reference Phan, Ordinario, Karshalev, Walkup, Shenk and Gorodetsky127]

Table I. Summary of the techniques employed to prepare optically active reflectin-based materials

Due to their unusual, skewed amino acid sequence, the recombinant production and purification of reflectins are somewhat complicated by their sequestration in inclusion bodies, requiring lengthy preparations to isolate prior to purification. To facilitate ease of production, in 2012, Kaplan and co-workers cloned a small portion of reflectin 1a (E. scolopes) containing one reflectin motif and part of a linker region, termed refCBA.[Reference Qin, Dennis, Zhang, Hu, Bressner, Sun, Crookes-Goodson, Naik, Omenetto and Kaplan128] Notably, they found that not only was this small portion of the sequence expressed as a water-soluble protein, thereby streamlining the purification process, it was also found to be sufficient enough to confer full-length reflectin properties such as high-refractive index, unique self-assembly, and thickness-dependent optical properties.[Reference Qin, Dennis, Zhang, Hu, Bressner, Sun, Crookes-Goodson, Naik, Omenetto and Kaplan128] Similarly, in 2017, Crookes-Goodson and co-workers discovered that reflectin thin films could be induced to scatter light following multiple, brief pulses of water vapor.[Reference Dennis, Singh, Vasudev, Naik and Crookes-Goodson129] Then, by creating truncated versions containing staggered dimers of the repeating reflectin motifs (1–2, 2–3, 3–4, and 4–5), thereby dissecting the roles of various regions of the protein, they were able to identify a small 23-amino acid region which retained the vapor-induced light-scattering properties of the full-length version.

These examples highlight one aspect of applying synthetic biology techniques to biomaterials engineering; by identifying small amino acid regions which maintain or enhance the desirable properties of their full-length counterparts, we can better understand the role of different regions of the protein. Understanding the structure–function properties of reflectins is fundamental to engineering reflectin-based biomaterials with desirable properties. With this knowledge, rational mutagenesis in order to enhance the intrinsic properties becomes the obvious next stage. For example, the introduction of a greater number of positively charged amino acids may lead to an increase in the attainable thickness of the fabricated films, due to an increase in electrostatic repulsion.

Any exploitation of reflectins for active camouflage would of course in all probability require an equally sophisticated biomimetic implementation of the neuromuscular control machinery that allows cephalopods to adapt their skin patterns to their local environment.[Reference Reiter, Hülsdunk, Woo, Lauterbach, Eberle, Akay, Longo, Meier-Credo, Kretschmer, Langer, Kaschube and Laurent130]

Indirect routes to synthetic biologic materials

As well as the direct production of proteinaceous materials from engineered host organisms as described in the above sections, there are also indirect routes to the production of materials using the tools of synthetic biology. This is typically achieved by engineering cells to express a multitude of bespoke enzymes—which, acting as catalysts, transform low-value starting materials (or even cell metabolites) into high-value products such as monomers for high-performance polymer fibers or adhesives. Replacing multi-step chemical synthesis steps with a single fermentation of engineered organisms could be an efficient and low-cost route to manufacture feedstocks of advanced materials that are already in use today. This approach of the “drop-in” replacement of existing monomers with bio-manufactured alternatives has the advantage of being low risk from a commercialization perspective—since demand for such feedstocks already exists.[Reference Adkins, Pugh, McKenna and Nielsen131] In future however, advances in synthetic biology and enzyme design could allow far more complex monomers to be produced using such a bio-manufacturing route—including large, chirally pure terpenoid-based molecules, for which the groundwork is already being laid.[Reference Friedman and Ellington19,Reference Cheallaigh, Mansell, Toogood, Tait, Lygidakis, Scrutton and Gardiner20] This section provides an overview of such methods and highlights the most significant examples reported in the literature.

Bio-derived monomeric precursors

Starting from simple sugars or polyols, engineered microbes can produce a diverse array of chemical building blocks, many of which are useful in polymer synthesis. Glycerol, for example, is easily derived from chemical or biologic trans-esterification of plant triglycerides (as a by-product of bio-diesel production), and has been used widely as a carbon source for growth in engineered strains but also as a precursor to propane-diol, glycerol carbonate, acrolein, and a host of other useful compounds.[Reference Mitrea, Trif, Cătoi and Vodnar132–Reference Sheldon134] In just one example of a bio-derivative of glycerol, an engineered strain of the bacterium E. coli was developed to allow the production of propane-diol at titers up to 130 g/L.[Reference Mitrea, Trif, Cătoi and Vodnar132,Reference Cervin, Soucaille and Valle135]

Unlocking chemical building blocks from lignocellulosic biomass has been the focus of intense research, giving rise to hundreds of useful compounds as reviewed in detail elsewhere.[Reference Isikgor and Becer133] Synthetic biology adds value to these bio-derived building blocks by diversifying the structures using designed pathways in engineered organisms. Furans are one class of compounds that can be produced through microbial fermentation of C5 and C6 sugars (derived from lignocellulosic or other renewable feedstocks). Furans are useful as monomers in their own right or as substrates for further modification. The production of p-xylene, for example, can be accomplished via cycloaddition of bio-derived dimethylfuran and ethylene (or from isobutanol or ethylene using other methods).[Reference Sheldon134] From p-xylene, bacterial strains have recently been developed to allow the efficient production of terephthalic acid,[Reference Luo and Lee136] and hence opening up routes to bio-based polyethylene terephthalate, polytrimethylene terephthalate, or polyaramid fibers such as Kevlar®. Besides providing drop-in replacements for conventional polymer precursors, synthetic biology routes can be designed to produce novel monomers. Recently, a computational approach to retrosynthetic enzyme pathway design identified routes to over 570,000 enumerated isomers from a core set of 17 monomers, illustrating the potential of synthetic biology for biochemical diversification of building blocks.[Reference Koch, Duigou, Carbonell and Faulon137]

Bio-derived organic acids

Organic acids are among the most common cellular metabolites that can be used in polymer synthesis. Itaconic acid is naturally produced in several organisms, notably the fungal species Aspergillus terreus, which gives around 80 g/L during sugar fermentation.[Reference Okabe, Lies, Kanamasa and Park138,Reference Ray, Smith, Simon and Saito139] The carboxylate and carbon–carbon double bond moieties of itaconic acid make it useful for modification or co-polymerization with a range of different monomers. 3-hydroxypropionic acid (3-HPA) is another useful acid, also possessing a β-hydroxy functionality.[Reference Ray, Smith, Simon and Saito139] 3-HPA is produced from a number of different feedstocks, including CO2 by certain photosynthetic organisms and in 96% yield (g/g) from 1,3-propanediol using an Acetobacter strain.[Reference Li, Zong, Zhuge, Lu, Fang and Sun140] The production of levulinic acid from lignocellulosic biomass is well established at a commercial scale.[Reference Bozell, Moens, Elliott, Wang, Neuenscwander, Fitzpatrick, Bilski and Jarnefeld141] Synthetic biology adds value through modification, such as the production of hydroxyacids 3- and 4-hydroxyvalerate, useful for the production of polyesters and (bio)degradable plastics, from levulinic acid using a modified strain of Pseudomonas putida.[Reference Martin and Prather142] Poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) is perhaps the best known degradable polymer, and L-lactic acid can be produced at scale from renewable sources such as corn starch or sugar cane.[Reference Pang, Zhuang, Tang and Chen143,Reference Tsuge, Kawaguchi, Sasaki and Kondo144] L-lactic acid is naturally produced in cells from pyruvate in the absence of oxygen and, under such conditions, the microorganism Corynebacterium glutamicum produces high levels of organic acids including L-lactic acid.[Reference Okino, Suda, Fujikura, Inui and Yukawa145] Furthermore, engineering of C. glutamicum offers a route to D-lactic acid in titers up to 195 g/L[Reference Okino, Suda, Fujikura, Inui and Yukawa145] and having both L- and D-lactic acid allows for the production of stereocomplex polylactides with improved melting and glass transition temperatures compared with traditional PLLA.[Reference Tsuge, Kawaguchi, Sasaki and Kondo144,Reference Tsuji and Ikada146] Succinic acid and adipic acid are relevant to the production of nylons, in combination with diamines (see below). As a central metabolite, succinic acid can easily be accessed from a number of organisms and is produced commercially in E. coli by the company Bioamber.[147] A large proportion (65%) of adipic acid derived from petrochemicals currently goes into nylon production, and hence an affordable bio-based replacement would be highly desirable.[Reference Tsuge, Kawaguchi, Sasaki and Kondo144,Reference Polen, Spelberg and Bott148] A number of engineered strains have been used to make adipic acid, the best of which currently is Thermobifida fusca B6, which naturally produces the compound at titers up to 2.23 g/L.[Reference Tsuge, Kawaguchi, Sasaki and Kondo144,Reference Deng and Mao149]

Bio-derived amines

Amines represent another major class of monomers that can be accessed biologically and include polyamines from diamines through to hexa-amines.[Reference Schneider and Wendisch150] Attention has centered on the polyamines putrescine and cadaverine, which can be derived from biodegradation of amino acids ornithine (or arginine) and lysine, respectively.[Reference Adkins, Pugh, McKenna and Nielsen131,Reference Schneider and Wendisch150] Putrescine derived from castor oil finds applications in polyamide production and is used to make the DSM products Stanyl™ and EcoPaXX™.[Reference Adkins, Pugh, McKenna and Nielsen131] Toward a biological source of putrescine, E. coli has been engineered to over-produce ornithine, with subsequent decarboxylation to yield the final product with titers of up to 24.2 g/L.[Reference Adkins, Pugh, McKenna and Nielsen131,Reference Qian, Xia and Lee151] The five-carbon diamine cadaverine is also useful for polyamide production and in a novel approach cadaverine has been produced up to 28.5 g/L by a co-culture of engineered E. coli strains—one strain to produce L-lysine and the other to decarboxylate it to the final product.[Reference Wang, Lu, Ying, Ma, Xu, Wang, Chen and Ouyang152]

Bio-derived terpenes

Terpenes are among the most diverse molecules produced in the biological world, with over 55,000 structures described,[Reference Kempinski, Jiang, Bell and Chappell153,Reference Leferink, Jervis, Zebec, Toogood, Hay, Takano and Scrutton154] and are a rich source of potential monomers for polymer production. The monoterpenes limonene and pinene have been functionalized via thiol-ene additions, thus permitting polycondensation reactions.[Reference Firdaus, Montero De Espinosa and Meier155] These terpenes and a diverse array of related structures can be renewably derived from plant biomass or by production in engineered microbial strains.[Reference Leferink, Jervis, Zebec, Toogood, Hay, Takano and Scrutton154,Reference Firdaus, Montero De Espinosa and Meier155] Further biological modification of terpenes facilitates access to novel polymers, as exemplified by the production of lactone monomers from the ketone-containing terpenes menthone and dihydrocarvone using Baeyer–Villiger monooxygenases.[Reference Messiha, Ahmed, Karuppiah, Suardíaz, Ascue Avalos, Fey, Yeates, Toogood, Mulholland and Scrutton156]

Inorganic composites and other bio-polymers

As well as engineering organisms to express proteins that are inherently structural, or protein-based enzymes that catalyze the production of material precursors (direct and indirect synthetic biologic materials, respectively), there also exist a plethora of other biological materials which could potentially be produced through the tools of synthetic biology. These include non-proteinaceous bio-polymers and materials, which are typically saccharide-based, and inorganic composite materials such a bone, horn, enamel, and nacre. A brief overview of such materials is given in this section, but such materials are generally more challenging to produce through synthetic biology at present and largely beyond the scope of this review.

Bio-polymers

Biological systems are adept at producing polymers, often as structural materials that confer rigidity, and protection. Polysaccharides are a good example of this and include cellulose, alginate, chitin, chitosan, and hyaluronan, which are biocompatible, biodegradable materials that find uses in medicine, foods, agriculture, and cosmetics.[Reference Anderson, Islam and Prather157] Synthetic biology provides an alternative source for these materials that does not rely on harvesting them from natural organisms. Chitin and chitosan are typically derived from shellfish, but recombinant production in microbes offers a more sustainable source, with better control over the degree of polymerization and acetylation for a well-defined end product.[Reference Anderson, Islam and Prather157,Reference Naqvi and Moerschbacher158] This was demonstrated in the gram-scale production of chitooligosaccharides in E. coli using genes from chitin-producing fungi.[Reference Samain, Drouillard, Heyraud, Driguez and Geremia159]

Many microbial species accumulate polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) inside the cell, where they function as storage molecules but are also useful as natural bioplastics. These (bio)degradable polyesters are comprised of short- (C3–C5) or medium-chain (C6–C14) monomers, with more than 150 different monomer structures described, and can be blended with other natural polymers such as polysaccharides to produce new materials.[Reference Li, Yang and Loh160] Synthetic biology is improving the production levels and costs for PHAs in engineered strains, as recently demonstrated for the non-conventional production host Halomonas species TD01, which grows under high-salt conditions that prevent the growth of contaminating organisms, thus obviating the need for costly sterilization procedures and equipment.[Reference Tao, Lv and Chen161]

Bacterial cellulose is another structural biological material that has attracted interest for a range of applications.[Reference Fuller162] Being produced from the bacterium Acetobacter xylinum (among others) as an extracellular, structural matrix of hierarchical, semi-crystalline microfibrils, the potential exists for gene editing to modify the properties of the material for useful purposes. A recently published UK Department of Defence project sought to employ the principles of synthetic biology (modification of key genes and pathways) to increase the production and purity of bacterial cellulose,[Reference Fuller162] and similar techniques could be employed to modify the mechanical properties for stand-alone materials or composites.

Bio-composites

Some of the most mechanically impressive and well-known examples of biological materials are hierarchical, inorganic-biopolymer composites—such as bone, enamel, and horn. Such materials often have exceptionally high strength, toughness, and durability considering their composition and the benign conditions under which they were fabricated. Nacre, for instance, is a protein–ceramic composite being comprised of over 95% calcium carbonate in the form of the mineral aragonite, yet its fracture toughness is over 3000 times higher than the pure mineral alone.[Reference Vincent163–Reference Currey165] This enhancement is attributed to a hierarchical “brick-and-mortar” type structure, where biomineralized aragonite platelet “bricks” are cemented together by a protein-based “mortar”.[Reference Wegst, Bai, Saiz, Tomsia and Ritchie164] Using synthetic biology, it should be feasible for similar performance improvements to be replicated for contemporary, high-performance ceramics (e.g., boron carbide)—if the brick-and-mortar structure could be replicated using engineered biomineralization and/or synthetic protein mortars. Recent advances in the fabrication of protein composites with 2D nanomaterials (e.g., graphene oxide, molybdenum disulphide, and hexagonal boron nitride) were recently reviewed by Demirel et al.,[Reference Demirel, Vural and Terrones166] who highlighted the potential for synthetic biology to tailor desired interactions and hierarchical assembly of the composites. Early examples include the use of a synthetic “diblock” protein for the creation of a graphene, cellulose composite,[Reference Laaksonen, Walther, Malho, Kainlauri, Ikkala and Linder167] or the use of squid ring teeth proteins with graphene oxide or 2D titanium carbides for biomorph actuators and stimuli-responsive electrodes, respectively.[Reference Vural, Lei, Pena-Francesch, Jung, Allen, Terrones and Demirel168,Reference Vural, Pena-Francesch, Bars-Pomes, Jung, Gudapati, Hatter, Allen, Anasori, Ozbolat, Gogotsi and Demirel169] Research into bio-composites produced or enhanced using the techniques of synthetic biology is still nascent, but there is a significant potential for “laboratory-grown” bio-composites to be an active area of research as the field of synthetic biology for materials matures.

Conclusions and outlook