No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

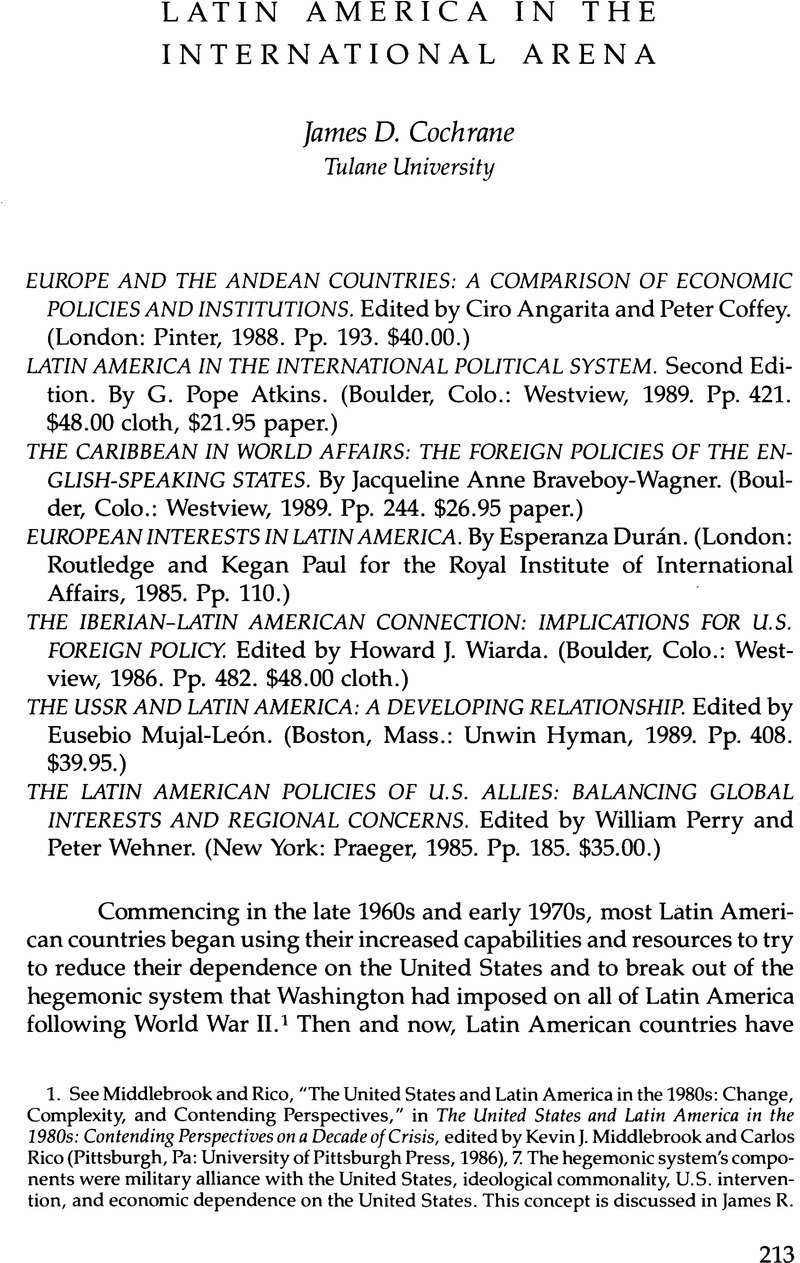

Latin America in the International Arena

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1991 by the University of Texas Press

References

Notes

1. See Middlebrook and Rico, “The United States and Latin America in the 1980s: Change, Complexity, and Contending Perspectives,” in The United States and Latin America in the 1980s: Contending Perspectives on a Decade of Crisis, edited by Kevin J. Middlebrook and Carlos Rico (Pittsburgh, Pa: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1986), 7. The hegemonic system's components were military alliance with the United States, ideological commonality, U.S. intervention, and economic dependence on the United States. This concept is discussed in James R. Kurth, “The United States, Latin America, and the World: The Changing International Context of U.S.-Latin American Relations,” in ibid., 61–86.

2. See Lincoln, “Introduction to Latin American Foreign Policy: Global and Regional Dimensions,” in Latin American Foreign Policies: Global and Regional Dimensions, edited by Elizabeth G. Ferris and Jennie K. Lincoln (Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 1981), 6.

3. John T. Rourke defines an international regime as “a complex of norms, treaties, international organizations, and transnational activity that orders an area of activity such as the environment or oceans.” See Rourke, International Relations on the World Stage, 2d ed. (Guilford, Conn.: Duskin, 1989), 541.

4. Lincoln, Latin American Foreign Policies, 14.

5. Carlos A. Astiz, “Mexico's Foreign Policy: Disguised Dependency,” Current History 66, no. 393 (May 1974):220–23, 225.

6. Establishing diplomatic relations with another country entails no cost, beyond a verbal statement recognizing the other country. Establishing diplomatic missions abroad does entail some costs, but they can be limited. An envoy can be accredited to more than one capital and the number of personnel assigned to a mission can be kept small.

7. Some of the restrictions are detailed by Atkins (pp.286–88). Others are identified in Luigi Einaudi, Hans Heymann, Jr., David Ronfeldt, and Cesar Sereseres, Arms Transfers to Latin America: Toward a Policy of Mutual Respect (Santa Monica, Calif.: Rand, 1973), 49–50; also in James D. Cochrane, “Latin America and Arms, 1966–1975: Notes on Acquisitions and Sources of Supply,” Revista/Review Interamericana 10, no. 2 (Summer 1980):156–72.

8. See U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, World Military Expenditures and Arms Transfers, 1988 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1989), 113.

9. Apart from the French dependencies and the former British colonies in the Commonwealth Caribbean, about the only Latin American and Caribbean countries to meet the criteria for development assistance are Haiti and Honduras.

10. See Bishare Bahbah, Israel and Latin America: The Military Connection (New York: St. Martin's, 1986).

11. Cole Blasier, The Giant's Rival: The USSR and Latin America, rev. ed. (Pittsburgh, Pa.: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1987).

12. See Vladimir Tismaneanu, “Castroism and Marxist-Leninist Orthodoxy in Latin America,” in Cuban Communism, edited by Irving Louis Horowitz, 7th ed. (New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction, 1989), 756–79.

13. Blasier, The Giant's Rival, 175.

14. See James D. Cochrane, “Contending Perspectives on the Soviet Union in Latin America,” LARR 24, no. 3 (1989):211–23.

15. Laurence Whitehead, “Debt, Diversification, and Dependency: Latin America's International Political Relations,” in Middlebrook and Rico, The United States and Latin America in the 1980s, 102.

16. Howard J. Wiarda, “United States Policy in Latin America,” Current History 89, no. 543 (Jan. 1990):31.

17. John McQuaid, “Latins Leaning Hard on U.S. for Aid,” The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, La.), 11 Mar. 1990, p. A-2.