Emma Molina Theissen is a tiny woman. When she speaks, her brown eyes sparkle behind her black-rimmed eyeglasses. Emma has lived for decades in exile with her family in Costa Rica. She left Guatemala in 1981, several weeks after she miraculously escaped from a secret military prison.

Emma was a militant in the Patriotic Worker Youth (JPT). At twenty-one, she had been politically active since her teenage years. She was returning to Quetzaltenango after attending a meeting in Guatemala City when her bus was stopped at a military checkpoint in Sololá. Such checkpoints were common at the time in Guatemala, which had been under continuous military rule since the 1954 coup d’état that ousted democratically elected president Jacobo Arbenz.Footnote 1

Soldiers searched the passengers, including Emma, and found documents she was charged with delivering to her comrades outlining a proposal to merge the JPT with the Guatemalan Workers’ Party (PGT), one of several Guatemalan resistance movements.Footnote 2 Eliminating the PGT was a top priority for the Guatemalan military, making Emma a potentially valuable source of information. She was brought to a military base in Quetzaltenango, Military Zone No. 17 (MZ17), where she was held incommunicado and interrogated about her comrades and their locations. She was savagely tortured and raped multiple times.

Emma’s eyes grow large when she talks about her audacious escape from MZ17. After about a week in captivity, military officials drove her around the city demanding that she identify her comrades and their safe houses. She refused. They brought her back to MZ17 and left her alone in her cell. She feared for her life.

Emma managed to slip out of her handcuffs. When she realized that the cell window was covered only with newspaper, she climbed out and made her way to the front gate of the military base. A guard asked her to identify herself. Pretending to be a prostitute whose services were no longer needed, she walked out of the base to freedom.

“I thought I had won. I had managed to escape!” Emma tells me. “I suffered greatly because of what they did to me, but I was alive!” She pauses, her voice lowering to a whisper. “But my moment of triumph became my greatest source of pain.”Footnote 3

For the military, Emma’s escape was a security debacle. The following day, three armed men raided her parents’ home in Guatemala City, intent on recapturing her. Emma’s mother, Emma Theissen Álvarez de Molina, and her fourteen-year-old brother, Marco Antonio, were there collecting some of their belongings. They had learned the night before of Emma’s detention and slept at a relative’s house for safety. That morning, they heard that Emma had escaped from MZ17. The intruders shackled Marco Antonio to a chair, and using Doña Emma as a shield, they searched the house. Not finding Emma, they untied Marco Antonio and placed a bag over his head. Doña Emma tried to intervene, but one of the men knocked her to the ground. They dragged Marco Antonio to a pickup truck and sped away.

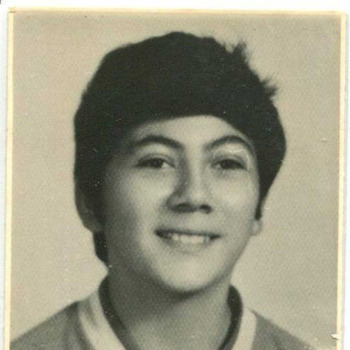

In the weeks and months that followed, the family searched for Marco Antonio in police stations, military barracks, hospitals, and morgues, to no avail. He is one of the forty-five thousand victims of forced disappearance during the thirty-six-year-long armed conflict (1960–1996), including an estimated five thousand children (CEH 1999; see Figure 1). For more than three decades, the crimes against Emma and Marco Antonio Molina Theissen went uninvestigated and unpunished.

Figure 1: Marco Antonio Molina Theissen was fourteen on October 6, 1981, when he was kidnapped and disappeared by the Guatemalan army. Photograph courtesy CEJIL.

On January 6, 2016, five senior military officials were arrested in the case.Footnote 4 A little over two years later, on May 23, 2018, four of those officials were convicted for planning and executing the crimes against Emma and Marco Antonio and sentenced to thirty-three to fifty-eight years in prison. Among those convicted were retired army generals long viewed as untouchable: former army chief Benedicto Lucas García, widely viewed as the architect of the Guatemalan army’s counterinsurgency strategy, and Manuel Callejas y Callejas, the powerful head of military intelligence and the alleged founder of the Brotherhood (Cofradía), an organized crime syndicate. Both of these men were at the heart of the counterinsurgency apparatus that unleashed indiscriminate violence on the Guatemalan population in the late 1970s and 1980s, including scorched-earth attacks on rural communities, massive systems of surveillance of suspected subversives, and the systematic use of terror to control rural and urban populations (CEH 1999). Despite peace accords signed in 1996, the military retained its power and privilege, and retired senior military officials like Lucas García and Callejas y Callejas reconfigured that power into new clandestine structures to preserve their privilege and protect their immunity (Reference Peacock and BeltránPeacock and Beltrán 2002; Reference SolanoSolano 2017).

In this article, I trace the history of the Molina Theissen family’s search for truth and justice to illustrate how survivors and families of victims have mobilized for justice, challenged entrenched structures of impunity, and successfully brought some of Guatemala’s most powerful military officials to justice. I emphasize the need to analyze the agency of survivors and families of victims and how they mobilize local and transnational networks of support in their pursuit of justice. Some scholars have emphasized international justice as a catalyst for justice in domestic jurisdictions (Reference Roht-ArriazaRoht-Arriaza 2008), while others focus on domestic mobilization as the primary impetus to local justice making (Reference CollinsCollins 2009). The Molina Theissen case illustrates the need to understand the complex, iterative, and nonlinear interplay between victims and civil society actors, domestic justice regimes, and international justice to better understand the factors contributing to domestic criminal prosecutions in contexts that may be in many other ways hostile to such endeavors.

A second thread of my analysis focuses on the evidentiary practices that led to the conviction in this case and that contribute to the production of truth and the rewriting of difficult pasts. In his study of the International Criminal Court, Richard Ashby Wilson calls on scholars to think about war crimes tribunals as complex social processes and urges the study not only of their outcomes but also the process by which they arise, the legal and evidentiary practices they adopt, and how legal judgments contribute to the historical record (Reference WilsonWilson 2011). In this article, I argue that domestic human rights prosecutions should similarly be examined in terms not only of outcome but also process. I show how the prosecution in this case mobilized victim testimony, fact and pattern witnesses, experts, and documentary evidence to build a command responsibility case against the intellectual authors of wartime atrocities. Human rights prosecutions may focus on specific episodes of violence, but they can also help us better understand broader patterns of state-sponsored violence, as well as resistance to it, thus contributing to the production of truth and creating new tools for the construction of new historical narratives about the past.

Building on this analysis, I show how these evidentiary practices created space for victims of human rights violations, including sexual violence, to testify and seek justice, generating confidence in a justice system that for too long had been unresponsive or even openly hostile to victims. This is particularly so in cases of wartime sexual violence, which scholars have long noted is rarely investigated or prosecuted (Reference MerryMerry 2006; Reference BoestenBoesten 2014). Victims maintain silence because of the societal shame and stigma imposed on women’s bodies, and because of the entrenched structures of impunity and sexism that deny women’s experiences (Reference Segato, Sonderéguer and CorreaSegato 2012; Reference Crosby and LykesCrosby and Lykes 2011; Reference JelinJelin 2012). When human rights prosecutions are victim-centered, they expand the possibilities for survivors like Emma Molina Theissen to see the courtroom as an institutional space in which they can finally break the silence and demand justice.

Ethnographic Research on Human Rights Trials

A month before the January 2016 arrests in the Molina Theissen case, the Open Society Justice Initiative (OSJI) invited me to monitor and report on the historic Sepur Zarco trial, the first ever in which Guatemalan courts were prosecuting wartime sexual violence, and the first time a domestic tribunal was hearing a case of sexual slavery (Reference BurtBurt 2019a). With the arrests in the Molina Theissen and other war crime cases, OSJI extended my research position. This allowed me to monitor the Molina Theissen trial in its entirety, from the pretrial and evidentiary phase hearings in 2016 and 2017 to the court trial in 2018. My direct observation of the proceedings, along with archival research and interviews with direct participants in the trial, are the basis for this ethnographic study of war crimes prosecutions in Guatemala.

The initial charges focused on the disappearance of Marco Antonio Molina Theissen and did not include the crimes of illegal detention, torture, and sexual violence committed against Emma Molina Theissen. Several months after the original charging documents were filed, the Attorney General’s Office amended the accusation to include crimes against humanity for the illegal detention, torture, and rape of Emma Molina Theissen (Reference BurtBurt 2016a). Prosecutors also included the charge of aggravated sexual assault, which would carry an additional sentence of up to eight years, the first time such a charge had been filed in a wartime case of sexual violence. I wondered why the crimes against Emma were not included in the initial indictment and why they were added later. As part of my research, I interviewed the parties to the trial at length, including several meetings with Emma, her sisters Ana Lucrecia and María Eugenia, and her mother Emma Theissen Álvarez de Molina.Footnote 5

In our first meeting, Ana Lucrecia told me that the prosecutors wanted to include the crimes against Emma when they first opened their investigation in 2011, but the family decided against this.Footnote 6 Emma’s recovery from the physical and emotional trauma was long and challenging, and they feared this would revictimize her. Emma told me that she testified before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which in 2004 found the State of Guatemala responsible for the forced disappearance of Marco Antonio. Her testimony, she said, was necessary to establish the sequence of events that led to her brother’s disappearance and identify those responsible.Footnote 7 Emma’s decision to focus on what happened to her in relation to her brother’s disappearance is consistent with research findings elsewhere that tell us that women who are survivors of sexual violence during war or authoritarian rule often remain silent about or underplay the abuses they endured, focusing instead on those who have been killed or disappeared (Reference Balardini and SobredoBalardini and Sobredo 2011; Reference JelinJelin 2012). Contributing to the silence of victims are social constructions of shame and stigma associated with being a victim of sexual assault, which Emma also expressed. Survivors of sexual assault also blame themselves for the abuses they suffered (Reference Segato, Sonderéguer and CorreaSegato 2012). Emma not only blamed herself for the sexual assault she endured; she also blamed herself for what happened to Marco Antonio. Because of this, she said, “I did not believe I deserved justice.”Footnote 8 Emma was also convinced that given the entrenched nature of impunity in Guatemala, justice was not possible.

What changed to make Emma believe that she deserved justice, and that justice was possible? In this study, I show how the work of justice making in Guatemala has transformed the way victims think about justice. Emma’s growing awareness of successful prosecutions for sexual violence crimes began to change the way she thought about her relationship to justice. Of particular importance was the Sepur Zarco trial, which began on February 1, 2016, just a few weeks after the arrests in the Molina Theissen case. The national and international community was riveted by the testimonies of fifteen Q’eqchi’ women, their faces covered by brilliantly colored shawls as they told harrowing stories about how the army arrived in their community, killed or disappeared their husbands, systematically raped the women, and then subjugated them to months of domestic and sexual servitude (Reference BurtBurt 2019a). On February 26, 2016, the court convicted the two defendants and sentenced them to 120 and 240 years in prison.

Emma learned that the Q’eqchi’ women did not have to testify in open court; rather, their pretrial testimony was recorded and broadcast into the courtroom. She learned that the women felt empowered after testifying, supported not only by the members of their community but by broad sectors of society and the international community. For Emma, the Sepur Zarco trial was transformative: “Learning about the Sepur Zarco case changed my heart, because they suffered the same thing I did. They suffered for much longer than I did, and they had the courage and the strength to testify in court…. I thought, if they could do it, so could I, and that changed me completely.”Footnote 9

Inspired by the women of Sepur Zarco, Emma came to believe that bearing witness to the horrendous crime against her brother was not enough. She wanted—and deserved—justice for herself as well. Emma came to see the courtroom as a legitimate space in which she could present her testimony and demand justice. Emma’s new belief in the transformative power of justice was evident in her closing remarks at the trial in May 2018. “The fact that our case has been heard in court has in itself been healing,” she told the panel of judges. “It has given us the opportunity to tell our truth and ask for the justice we deserve” (Reference Burt and EstradaBurt and Estrada 2018a).

It is doubtful I would have known to inquire about this change in the indictment and how it came about had I not been engaged in direct observation of the Molina Theissen trial from start to finish. This speaks to the value of grounded ethnographic research of human rights prosecutions, despite the challenges of this type of qualitative research. Proceedings are often long and drawn out: in this case, it was two years and five months from the arrests to the judgment.Footnote 10 My commitment to this research practice stems from my positionality as a researcher rooted in the tradition of activist scholarship that envisions the researcher not as someone who is “neutral” about the issues they are examining but rather one who rigorously and critically engages research questions and methods to interrogate structures of systemic inequality and injustice with the aim of contributing to social change (Reference HaleHale 2008). Accurate and sustained reporting on often contentious proceedings such as these contributes to the production of knowledge about the challenges facing those pursuing justice that can be of use to victims, activists, policymakers, government authorities, and other stakeholders. It also demonstrates how local justice efforts are informed by and help constitute the global justice and human rights regime.

¿Dónde está Marco Antonio? The Search for Truth and Justice

Emma Theissen Álvarez de Molina filed a missing person’s report to the National Police and a writ of habeas corpus before the courts the very day Marco Antonio was kidnapped.Footnote 11 From that moment on, she dedicated her life to searching for her son. She and her husband, Carlos Augusto Molina, quit their jobs. They searched for Marco Antonio in police stations, hospitals, prisons, and military bases. They filed more writs of habeas corpus. They petitioned the Human Rights Ombudsman, an autonomous governmental body constitutionally mandated to defend human rights, to initiate a special investigation. They met with senior army officials, including Colonel Francisco Gordillo Martinez, the commander of MZ17, where Emma had been held captive. Every official they consulted denied knowledge of Marco Antonio’s whereabouts. By 1984, growing repression and targeted attacks against members of the Molina Theissen family forced them to leave Guatemala. From exile, it was nearly impossible to continue the search for Marco Antonio.

In 1996, under the aegis of the United Nations, the Government of Guatemala signed peace accords with the National Revolutionary Unity of Guatemala (URNG), ending the armed conflict. The peace accords included provisions for the reintegration of guerrilla combatants into political life, the demilitarization of the Guatemalan state, and reforms to consolidate the rule of law, construct a more inclusive economy, and end systemic racism against the indigenous population (Reference JonasJonas 2000). The peace accords called for the creation of the Commission for Historical Clarification (CEH) to investigate wartime human rights violations. An earlier inquiry, the Interdiocesan Project for the Recovery of Historical Memory, was launched by the Catholic Church in 1995 (REHMI 1998). Congress passed the Law of National Reconciliation on December 27, 1996, overturning the 1986 self-amnesty law that shielded state agents implicated in human rights violations from criminal prosecution. This legislation allowed for amnesty for political crimes but prohibited amnesty for genocide, forced disappearance, torture, and other international crimes.Footnote 12

These developments inspired hope in the Molina Theissen family that they might at last learn the truth about what happened to Marco Antonio, recover his remains and give him a proper burial, and perhaps bring those responsible to justice. Ana Lucrecia and María Eugenia Molina Theissen traveled to Guatemala to present Marco Antonio’s case to REHMI and the CEH. They also petitioned the Human Rights Ombudsman to reopen the investigation into Marco Antonio’s disappearance.Footnote 13

But there was no progress in the case. Despite the 1996 legal exclusion of amnesty for international crimes, there was neither the capacity nor the political will to investigate wartime atrocities (Reference KempKemp 2004). International pressure led to trials in a handful of high-profile cases, such as the 1990 murder of anthropologist Myrna Mack and the 1998 murder of Bishop Juan Gerardi, as well as a few massacre cases (Myrna Mack Foundation 2004). But the defendants were mostly foot soldiers or low-level military officials, rarely the intellectual authors of the crimes, and each case was rife with procedural challenges and revealed the danger of pursuing justice in postwar Guatemala (Reference SanfordSanford 2003; Myrna Mack Foundation 2004; Reference DillDill 2005; Reference GoldmanGoldman 2008). In this context of institutionalized impunity, denial narratives claiming that the Guatemalan army fought a heroic battle against international communism flourished. Atrocities were flat-out denied or justified as a necessary means to that end.

Denied justice at home, victims of wartime atrocities began to look to regional and international courts. Victims of the Guatemalan armed conflict have filed dozens of cases before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), and since 1996, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights has handed down at least fourteen judgments condemning the State of Guatemala for wartime atrocities. These judgments, which are binding on state parties, include court orders to the State of Guatemala to investigate, prosecute, and punish the perpetrators (Reference QuintanaQuintana 2016). Victims have also filed charges in foreign courts. In 1999, Nobel Peace Laureate Rigoberta Menchú filed genocide charges against the Guatemalan high command before the Spanish National Court, invoking the principle of universal jurisdiction.Footnote 14 A Spanish judge’s effort to prosecute the generals was quashed when the Guatemalan Constitutional Court rejected his request to have them extradited to Spain (Reference Roht-ArriazaRoht-Arriaza 2008). These international justice efforts generated pressure on the Guatemalan legal system to respond to victims’ demands for legal redress, but it was not until a maverick new leader, Claudia Paz y Paz, was named Attorney General in 2010, and some key judicial reforms were put in place, that there was any real movement in the Guatemalan legal system. (I explore these changes this further below).

The Molina Theissen family pursued the first of these strategies. In September 1998, with the support of the Guatemalan victims’ association Mutual Support Group (GAM) and the Center for Justice and International Law (CEJIL), they filed a petition before the IACHR against the State of Guatemala for the forced disappearance of Marco Antonio. Guatemala signed a friendly settlement in April 2003, acknowledging state responsibility for Marco Antonio’s disappearance and promising to criminally prosecute those responsible and provide reparations to the family. It failed to do so, however, prompting the IACHR to refer the case to the Inter-American Court.

In April 2004, the Inter-American Court found the State of Guatemala responsible for the forced disappearance of Marco Antonio Molina Theissen and ordered it to investigate, prosecute, and punish the perpetrators and mandated reparations.Footnote 15 The Guatemalan government adopted what scholars refer to as an “a la carte” approach to fulfilling the court’s orders (Reference EngstromEngstrom 2019). It acknowledged the state’s responsibility, publicly apologized to the family, named a school after Marco Antonio, and paid financial reparations. But it failed to return his remains or create a national genetic database, and no state action was taken to hold perpetrators accountable.Footnote 16

Another decade would pass before the defining breakthrough in the case with the 2016 arrests. What made this possible? Scholarly enthusiasm about international justice aside, we see in this and other cases that international justice does not translate automatically into judicial action in domestic jurisdictions. It may generate pressure on local jurisdictions, but without independent local prosecutors and judges, human rights prosecutions are unlikely to advance (Reference Pion-BerlinPion-Berlin 2004; Reference BurtBurt 2009; Reference CollinsCollins 2009). In the next section, I explore the factors that strengthened prosecutorial and judicial autonomy and facilitated the rise of new leadership in the country’s legal system, two essential elements to understand the successful prosecution of wartime atrocities in Guatemala.

Transformations in Guatemala’s Justice System

Impunity for wartime and other crimes bred lawlessness, violence, and corruption. Organized crime networks, many of them connected to old guard military officers, flourished, creating parallel security structures, co-opting state institutions for personal gain, and targeting government officials and human rights defenders who dared challenge their power (Myrna Mack Foundation 2004). In response, local and international civil society groups began lobbying for the creation of an international body to help Guatemala combat growing lawlessness by strengthening legal institutions and the rule of law. After a series of high-profile killings, the Guatemalan government acceded to an unprecedented international intervention to promote the rule of law in a sovereign state, signing a treaty-level agreement with the UN in December 2006 to establish the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) (OSJI 2016).

An independent body, CICIG’s mandate was to support the Attorney General’s Office and other state institutions in their investigations of sensitive and complex criminal cases. CICIG could propose public policies as well as judicial and legislative reforms to further its mission of strengthening prosecutorial and judicial autonomy, combating corruption and organized crime, and strengthening the rule of law. In 2015, an investigation of a multimillion-dollar customs fraud ring spearheaded by CICIG and the Attorney General’s Office led to the arrest of some two hundred government officials and economic elites, including sitting president Otto Pérez Molina, catapulting CICIG to the international spotlight (Reference Ahmed and MalkinAhmed and Malkin 2015).

CICIG’s mandate did not include investigation of wartime atrocities, but by strengthening judicial and prosecutorial independence, it helped create the conditions to eventually do so (Reference Burt and EstradaBurt and Estrada 2017). It helped establish new procedures for the selection of the attorney general and Supreme Court magistrates, which facilitated the rise of a new generation of independent judges and prosecutors, including the first female attorney general in Guatemalan history, Claudia Paz y Paz (2010–2014), and her successor, Thelma Aldana (2014–2018). Both have been widely recognized for their independence and determination to combat institutionalized impunity for serious crimes, including wartime human rights violations (OSJI 2016). CICIG also supported a series of reforms that helped professionalize the Attorney General’s Office and provide it with new tools and capacity to conduct complex investigations that began to close in on key networks of corruption and impunity. As Paz y Paz told me: “CICIG provided a framework for independent prosecutors to do their job.”Footnote 17

Paz y Paz leveraged this framework to aggressively pursue wartime atrocity cases. She created a specialized Analysis Unit for conflict-era cases to assist prosecutors with complex criminal investigations, and established protocols to guide investigations of wartime human rights violations, including a specific protocol for investigating cases of sexual violence.Footnote 18 Prosecutors received special training in international human rights law and were encouraged to collaborate with civil society organizations, survivors, and families of victims to collect evidence and build their cases. A wave of indictments against perpetrators of large-scale massacres, forced disappearance, and sexual violence followed (Reference Burt and BermúdezBurt 2019b).

Working with the chief justice of the Criminal Chamber of the Supreme Court, César Barrientos, CICIG helped create a specialized high-risk court system to adjudicate complex criminal cases. The high-risk courts are centralized in Guatemala City, but they have jurisdiction over the entire country. This arrangement was designed to stem corruption, intimidation, and influence-peddling common in local jurisdictions. These courts enjoy heightened security measures to guarantee the safety of judges, prosecutors, and litigants. This strengthened judicial independence and allowed for the prosecution of cases involving drug trafficking, organized crime, official corruption, and gang violence, as well as wartime human rights violations (CIJ 2016).

Another key legal development facilitating human rights prosecutions in Guatemala came in 2009 and 2010, when Magistrate Barrientos issued rulings establishing that sentences of the Inter-American Court are “self-executing,” meaning that they are judicially enforceable in Guatemalan courts and that rulings issued by local courts cannot impede or obstruct their implementation.Footnote 19 This created a new framework for government prosecutors to pursue criminal investigations in conflict-era cases in which the Inter-American Court had issued judgments, including the Molina Theissen case, revealing the iterative nature of the relationship between local and international justice. The Attorney General’s Office developed a list of ten priority cases, the majority of which were cases with sentences from the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, including the Molina Theissen case.Footnote 20 In 2011, government prosecutors traveled to Costa Rica to take the testimony of Emma Molina Theissen, the first real action the Attorney General’s Office had taken in the case. But further progress would take several more years, as virtually all of the resources of the Attorney General’s Office focused on the first leadership case in Guatemalan legal history: the genocide trial of former de facto president Efraín Ríos Montt (1982–1983).Footnote 21

For years, Ríos Montt enjoyed congressional immunity and could not be prosecuted. When his congressional mandate ended on January 14, 2012, Attorney General Paz y Paz charged him with genocide and crimes against humanity. Ríos Montt’s defense lawyers filed over one hundred legal motions, delaying the trial for more than a year. After a tumultuous three-month public trial, on May 10, 2013, Ríos Montt was convicted and sentenced to eighty years in prison. The backlash was swift. Ríos Montt’s military backers convened street protests demanding his freedom, while the powerful conglomerate representing economic elites, the Coordinating Committee of Agricultural, Commercial, Industrial, and Financial Associations (CACIF), publicly called on the Constitutional Court to overturn the conviction. Ten days later, the Constitutional Court partially nullified the proceedings, vacating the Ríos Montt conviction. Emboldened, the right wing intensified its intimidation campaign. Pro-military groups filed frivolous lawsuits against judges, prosecutors, and expert witnesses in the case. Paz y Paz was forced out as attorney general six months early and left the country for fear she would be arrested. Cases under indictment moved forward, but no new charges were filed in conflict-era cases (Reference BurtBurt 2016c).

In mid-2015, mass anti-corruption protests erupted in Guatemala, altering the political landscape dramatically. The protests emerged in support of investigations by CICG and the Attorney General’s Office into official corruption and demanding the arrest of President Pérez Molina and others implicated in the scandal. After months of protests, on September 3, 2015, Pérez Molina stepped down and was arrested. A retired general implicated in war crimes who had managed to evade sanction but who now faced charges of corruption and abuse of authority, Pérez Molina embodied the connection between past violence and present-day corruption in Guatemala (Reference SanfordSanford 2013).

These developments sparked new life into the legal battle against impunity, not only for corruption, but also for wartime atrocities. A defining moment was the January 2016 arrest of eighteen senior military officials, several of whom were at the center of the counterinsurgency apparatus that operated in Guatemala in the late 1970s and early 1980s, in the Molina Theissen and CREOMPAZ mass disappearance cases (Reference BurtBurt 2016d). The Sepur Zarco sexual violence and sexual slavery trial commenced on February 1, 2016, and after four weeks of compelling public hearings, the court convicted two military officials and sentenced them to 140 and 240 years in prison. In June 2016, a pretrial judge ordered eight officials to trial in the CREOMPAZ case (Reference BurtBurt 2016b). In August 2016, a former special forces (Kaibil) soldier was arrested, charged, and later convicted for his role in the 1982 Dos Erres massacre, in which 200 civilians were killed (Reference Burt and EstradaBurt and Estrada 2018c). A pretrial judge ordered the men charged in the Molina Theissen case to trial in March 2017, though it took another year for the trial to commence, revealing the slow pace of Guatemala’s accountability efforts. Nevertheless, as I will show in the next section, the evidentiary practices deployed by the plaintiffs in the Molina Theissen trial illustrate the potentially transformative nature of human rights prosecutions.

The Molina Theissen Trial

The trial commenced on March 1, 2018, with Judge Pablo Xitumul of High Risk Court “C” presiding, alongside Judges Eva Recinos Vásquez and Elvis Hernández Domínguez. On the first day of the trial, the prosecution presented the accusation, then Judge Xitumul invited the defendants to address the court. Two of the defendants spoke briefly. Callejas y Callejas declined to speak. Benedicto Lucas García, on the other hand, addressed the court at length on the second day of the trial.

Deny and deflect

At eighty-five, Lucas García is spry and alert (see Figure 2). Silver wire-rimmed glasses frame his angular face. He is surprisingly short, but he has a commanding presence. His brother, General Romeo Lucas García, who was president between 1978 and 1982, appointed him chief of the General Staff of the Guatemalan Army in August 1981. Lucas García reoriented the army’s counterinsurgency strategy in an effort to eradicate the guerrilla movements and prevent a revolutionary takeover, which resulted in mass killings, forced displacement of entire communities, and systematic use of torture and sexual violence against noncombatant populations (CEH 1999). For the Guatemalan military, he is a war hero. The judicial guards regularly saluted him when he entered the courtroom, in handcuffs.

Figure 2: Retired general and former chief of the Guatemalan Army Benedicto Lucas García at the Molina Theissen trial. Photograph courtesy @VerdadJusticiaG.

Lucas García, who was charged with command responsibility for the crimes against Emma and Marco Antonio Molina Theissen, insisted on his innocence: “I am not a thief, I am not corrupt, I am not a rapist, nor am I a kidnapper. I am a person of integrity” (Reference Burt and EstradaBurt and Estrada 2018d). He recounted his military training at Saint Cyr in France, his service as an army officer, and the honors and awards he had received over the years to demonstrate his moral solvency. His presence on the battlefield during the height of the counterinsurgency war and his direct command over the troops proved his leadership and his service to the nation. He accused REHMI—which found that the vast majority of the two hundred thousand victims of the conflict were noncombatant civilians—of falsifying information “to make the army look bad.” “The army didn’t commit abuses;” therefore, he asserted, he “could not be held responsible.” He did not directly address Emma’s assertion that she had been detained by the army, but he dismissed it indirectly: “We fought the guerrilla in combat. In Guatemala there were no political prisoners” (Reference Burt and EstradaBurt and Estrada 2018d).

Lucas García then pivoted from outright denial to deflection. If there were abuses, he stated, they were the responsibility of the judicial police or right-wing death squads, not the army; so, again, he was not responsible. Despite his earlier emphasis on his military leadership and his leading role in defeating the guerrillas on the battlefield, he insisted that he did not emit orders—he only received them from the Minister of Defense—nor did he have command responsibility over troops.

Lucas García’s next tack was to challenge the legitimacy of the court itself. He called the case a “hoax” and said he was being persecuted by those he defeated on the battlefield. “My brother is no longer alive. So now I am the political objective,” he intoned (Reference Burt and EstradaBurt and Estrada 2018d). Lucas García’s statements were drawn from the same playbook as the denial narratives espoused by the Guatemalan military. Whereas the militaries in some Latin American countries, such as Chile and Argentina, have acknowledged their responsibility for grave human rights violations and have asked forgiveness, the Guatemalan military continues to deny its role in atrocities and remains unrepentant.

“His face is forever etched in my memory”

That same afternoon, the prosecution called its first witness, Emma Theissen Álvarez de Molina, to testify about the events of October 6, 1981. The night before, she and her husband had learned of Emma’s capture and slept at a relative’s house for safety. The next morning, she returned to the house with Marco Antonio to retrieve some items. Ana Lucrecia came by to tell them that Emma had escaped and urged them to leave the house quickly. Doña Emma told the court that shortly thereafter, two armed men forced their way into her home. She described how they shackled Marco Antonio to a chair and forced her to go with them as they searched the house for Emma. She described how one of the men struck her to prevent her from stopping them as they untied Marco Antonio and dragged him away, and how she struggled to stand and ran outside, only to see the men speed away in a truck. The courtroom was quiet, the air thick with the knowledge that Doña Emma still did not know what happened to her son (Reference Burt and EstradaBurt and Estrada 2018d).

Judge Xitumul asked Doña Emma if she recognized among the defendants any of the men who kidnapped Marco Antonio. She stood and walked toward the holding cell where they were sitting. She looked at them, then turned to face the judges (see Figure 3). She lifted her left arm and pointed to Hugo Zaldaña Rojas: “The man who is sitting on the far left, that is him. His face is forever etched in my memory” (Reference Burt and EstradaBurt and Estrada 2018d). Zaldaña is the same person Emma had identified as the intelligence officer in charge of her during her captivity at MZ17.

Figure 3: During her testimony in court, Emma Theissen Álvarez identifies the man who kidnapped her son in 1981. March 5, 2018. Photograph by the author.

Emma’s sisters, María Eugenia and Ana Lucrecia, testified next. María Eugenia recounted the family history of political activism that led the military to categorize them as “enemies of the state.” She described how their father, Carlos Molina, had been detained twice following the 1954 coup for his opposition to the military. She noted that Emma had been detained before, in 1976, when she was a student leader, along with her boyfriend, Julio César del Valle Cóbar. As minors, they were freed. In 1980, del Valle was extrajudicially executed, prompting Emma’s move to Quetzaltenango. Both sisters testified about Emma’s detention, torture, and rape, the forced disappearance of Marco Antonio, and the terrible impact it had on their family. They told the court that in 1984, the family left Guatemala, after María Eugenia’s husband, Héctor Alvarado, was also killed (Reference Burt and EstradaBurt and Estrada 2018j).

“They did this in retaliation for my escape”

The prosecution next focused on proving the crimes committed against Emma Molina Theissen. Emma’s direct testimony was central to the case, but she was not required to testify in person. Instead, her recorded testimony, which a pretrial judge admitted into evidence in 2011, was broadcast into the courtroom. This practice was adopted during the Sepur Zarco trial at the request of the plaintiffs in order to minimize the revictimization of sexual violence survivors by not requiring them to repeat their testimony and confront their alleged assailants in person.Footnote 22

Emma described her involvement in the Guatemalan resistance movement; her capture on September 27, 1981, and her escape a week later; and how she did not learn until months later about the kidnapping of her brother. She testified that the military officials interrogated her, seeking information about her comrades and their locations, and then tortured and raped her on multiple occasions. She recounted how her captors drove her around Quetzaltenango, pressuring her to identify her PGT comrades and how her refusal to cooperate infuriated them. She spoke about her escape, about a friend who aided her, and how she eventually left Guatemala for Mexico. Emma’s testimony established the chain of events that led to her brother’s disappearance and a motive: “My family and I are certain that they did this in retaliation for my escape, and for my refusal to give them the information they were looking for” (Reference Burt and EstradaBurt and Estrada 2018f).

After her testimony, Emma wrote on Twitter: “After the tenth hearing of this long delayed but profoundly healing justice, I reaffirm with all my strength: #IChooseToLive.”Footnote 23 The hashtag trended in Guatemala, symbolizing, much like the #MeToo movement, the decision by survivors of sexual violence to speak out and demand justice (Reference Page and ArcyPage and Arcy 2020). For years, Emma suffered in silence, in exile, while the government denied responsibility for what happened to her. By speaking out, Emma was breaking the silence, reclaiming her story, and exercising her right as a citizen to seek justice. Emma told me that she felt so empowered that she decided to give her final declaration to the court in person, even though it would mean confronting her tormentors in open court.Footnote 24 I discuss this further below.

Several fact witnesses corroborated Emma’s testimony. One protected witness testified about assisting Emma after her escape from MZ17. She described Emma’s delicate mental and physical state, noting that a physician diagnosed and treated her for psychosis resulting from being tortured and violently and repeatedly raped. The prosecutor read aloud the testimony of a second fact witness, Isidro Mérida, who was no longer living. Mérida, a PGT leader, stated that he was supposed to meet Emma in Quetzaltenango on September 27, 1981, but she never arrived. Several days later, he said, he observed Emma being driven around Quetzaltenango in a military vehicle. Another protected witness, also a former PGT leader, testified that he too saw Emma in a military vehicle in Quetzaltenango (Reference Burt and EstradaBurt and Estrada 2018k).

Building the case: Evidentiary practices

Richard Ashby Wilson (Reference Wilson2011) has argued that examination of legal and evidentiary practices can help us understand how prosecutors build cases, how courts weigh evidence and make their determinations, how this shapes ongoing legal practice, and how legal judgments contribute to the historical record. Here, I briefly examine the evidentiary practices at work in the Molina Theissen trial to better understand how a conviction was achieved. In addition to the testimonies of direct victims and fact witnesses, the plaintiffs brought together different types of evidence to demonstrate the facts of the case and that these types of crime—the forced disappearance and attacks against children of dissidents, in the case of Marco Antonio, and torture and sexual violence against detainees in the case of Emma—were not isolated incidents but official state practice.Footnote 25

The plaintiffs presented documentary evidence and called on pattern witnesses and experts to demonstrate that the military practice of targeting the children of suspected dissidents was state policy. First, they referred to the CEH report, which documented this practice and estimated that five thousand children were disappeared during the armed conflict. Two pattern witnesses illustrated that what happened to Marco Antonio was not an isolated incident. Adriana Portillo-Bartow testified that the army forcibly disappeared six members of her family, including her daughters Glenda and Rosaura Carrillo Portillo, ages nine and ten, and her infant stepsister, Alma Portillo, in 1981. Portillo-Bartow’s father, Adrian Portillo Alcántara, who was among those disappeared, was a political leader in the Revolutionary Organization of the People in Arms (ORPA), and three of her siblings were combatants.Footnote 26 “We joined ORPA to change the political and social situation in Guatemala,” she said. “We were aware of the risks we were taking. But we never imagined that the government would make our children targets in order to terrify, paralyze, and punish their parents” (Reference Burt and EstradaBurt and Estrada 2018g). She still does not know what happened to her daughters and other family members. A second pattern witness, whose identity was protected, said that he was captured in July 1981 and brought to MZ17, the same military base where Emma was detained, where he was tortured. The whereabouts of his son and nephew, who were with him when he was captured, remain unknown.

A former military intelligence official who served under the defendants in this case between 1981 and 1982 also testified. He recounted various forms of torture the army used against suspected subversives. “Everyone who was detained was tortured,” he stated. “Women captives were routinely raped” (Reference Burt and EstradaBurt and Estrada 2018e). Expert witnesses provided further documentary evidence and research on the army’s systematic use of torture and other human rights violations. The historian Marc Drouin, who has extensively studied Guatemalan military doctrine and practice, presented official documents to demonstrate that the army viewed the Molina Theissen family as a military objective. His research showed that torture, sexual violence, and enforced disappearance were not merely forms of punishment; they were methods derived from military doctrine that were systematically deployed against internal enemies “as weapons of war, just like a rifle or a bullet” (Reference Burt and EstradaBurt and Estrada 2018b).

Expert witness Fernando Cabrera Galindo testified about the military practice of using military zones as detention and torture centers, and the systematic nature of sexual violence and forced disappearance. Sonja Perkiç documented the army’s systematic practice of sexual violence against women detainees. Carlos Martin Beristain, a psychologist and expert on victims of human rights violations, testified that the forced disappearance of Marco Antonio was intended to produce harm to the Molina Theissen family in reprisal for Emma’s escape from military custody. The failure of the Guatemalan State to tell the family the truth about what happened to Marco Antonio and to return his remains constitutes a form of ongoing and permanent torture, he said.

Expert witnesses testified about key aspects of military doctrine, organization, and practice. This was critical to establishing the chain of command and the nature of military intelligence operations, which helped establish the link between the defendants and the crimes. Héctor Rosada Granados, a military sociologist who represented the Guatemalan government in the peace negotiations, testified about the functional responsibilities of the defendants based on their positions in the chain of command (Reference Burt and EstradaBurt and Estrada 2018h). Rosada testified that the chief of Military Intelligence, or G2, oversees the army’s intelligence-gathering operations and supervises and monitors all aspects of implementation. The G2 (Callejas) is a member of the Army General Staff, which is commanded by the chief of the General Staff (Lucas García). He has command over all members of the military intelligence system, meaning he gives orders, establishes tasks, and sets deadlines for completion of those tasks. Each military base has a chief intelligence official (Zaldaña Rojas, in the case of MZ17) who is under the command of the G2 (Callejas), as well as the chief of their local military base (Gordillo).

The testimony of retired Peruvian army general Rodolfo Robles corroborated Rosada’s testimony about the military chain of command and further explained how the communication channels between Military Intelligence and the High Command operated. He also explained the logic behind the crimes. After the 1954 coup, Robles said, the Guatemalan Constitution outlawed the PGT and sought its eradication: “Communism was not a political opponent to be combatted, but an enemy to be exterminated” (Reference Burt and EstradaBurt and Estrada 2018h). Military Intelligence developed specialized units to obtain intelligence about the PGT, which they were required to transfer to the G2 (Callejas). Robles explained that as soon as the MZ17 intelligence official Hugo Zaldaña learned that Emma Molina Theissen possessed PGT documents, he viewed her as a critical source of military intelligence. The High Command had to know about Emma’s capture, since military doctrine required Zaldaña to report intelligence about the PGT to Callejas, who in turn would have had to inform his superior officer, army chief Lucas García.

Robles also discussed Emma’s escape, which he said was not merely a security breach but a major embarrassment for the intelligence services. The response was the intelligence operation to recapture Emma that led to abduction of her brother. Robles testified that the order to carry out this operation had to come from Callejas and his superior, Lucas García. The prosecution introduced as corroborating evidence documents found in Gordillo’s home after his arrest demonstrating that he and the High Command were aware of Emma’s detention and escape, as well as the intelligence operation to recapture her. In one of these documents, Callejas ordered an inspection of MZ17 in response to Emma’s escape and recommended security improvements.

“Sepur Zarco changed my heart”

At the close of the proceedings, the parties were invited to address the court. Here I want to return to the words of Emma, whose prerecorded testimony was broadcast into the courtroom earlier in the proceedings, but who had not yet spoken directly to the tribunal. During the course of the trial, Emma decided she wanted to address the court. She told me she was terrified to do so, since she would have to face her tormentors, but she felt it was necessary for her healing process.Footnote 27 Unlike her 2011 testimony, she was speaking not just as a fact witness but as a claimant demanding justice (see Figure 4). In her in-person court appearance, on May 21, 2018, Emma told the court:

I want to tell you that they did not kill me, but what they did profoundly destroyed my life. For many years I was filled with terror and suffering. I did not consider myself worthy of living. I believed that my life was a life stolen from my brother. The fact that by escaping I had managed save my own life filled me with pride, but this became my worst mistake, the worst moment of my life … because it resulted in the kidnapping and the disappearance of my little brother…. I have lived crushed by guilt, shame, pain, and disgust…. They desecrated my body, they violated all my humanity. I will carry that for the rest of my life. (Reference Burt and EstradaBurt and Estrada 2018a)

Figure 4: The Molina Theissen family at the trial in Guatemala City. Photograph courtesy @VerdadJusticiaG.

But she also told the court that having her testimony heard in court, seeing a panel of judges listen to her and believing her words, was transformational: “The love of my family and all of those who accompanied me during this process of seeking justice has given me strength. The very fact that our case has been heard in court has in itself been healing. It has given us the opportunity to tell our truth and ask for the justice we deserve” (Reference Burt and EstradaBurt and Estrada 2018a).

Dori Laub, the Holocaust scholar, has remarked that memory is necessarily a dialogic process. Survivors of mass atrocities must be willing to narrate what they suffered, but there must also be an “other” willing to listen to and acknowledge those stories and the pain buried therein (Reference Laub, Felman and LaubLaub 1992). For decades, Emma did not believe she deserved justice, nor did she believe justice was possible. For years, Emma faced what Laub (Reference Laub, Felman and Laub1992) calls a “dialogic vacuum,” the result of institutionalized impunity and the refusal of the state to acknowledge the harm done to her. The shifts in the Guatemalan justice system, in which prosecutors began actively investigating wartime atrocities and judges began handing down convictions against the perpetrators of these crimes, created the possibility for dialogue for the first time. In her closing remarks, Emma affirms that speaking her truth and being heard by a court of law was “in itself” transformational. Emma’s realization illustrates Elizabeth Jelin’s notion of the multiple temporalities of victim testimonies. Victims may choose not to give their testimony in certain contexts but may do so in others, depending on who is asking the questions, in what context they are being asked, and who—if anyone—is listening (Reference JelinJelin 2014). Emma saw that prosecutors and judges believed what sexual violence survivors like her said happened to them. Justice-making changed Emma’s way of thinking. After years of believing she did not deserve justice and that justice was not accessible to her, she came to view the courtroom as a space in which she could speak about what happened to her and be heard. For Laub, this kind of dialogue is the foundation for the construction of historical memory.

In a public, high-profile case such as this, this dialogue naturally extends beyond the reach of the courtroom. Emma told me that she was deeply moved by the expressions of support and solidarity for her pursuit of justice from broad swaths of Guatemalan society, including human rights activists, social workers, journalists, artists, students, other sexual violence survivors, and ordinary citizens, as well as members of the international community (see Figure 5). On the day of the verdict, the small courtroom was packed with people demonstrating their support, including international dignitaries and school children carrying signs saying #WeAreAllMarcoAntonio.Footnote 28

Figure 5: María Eugena and Emma Molina Theissen at a concert in remembrance of their brother, Marco Antonio. Guatemala City, December 9, 2016. Photograph by the author.

The verdict: Guilty as charged

On May 23, 2018, the court unanimously found four of the five defendants—army chief Benedicto Lucas García; military intelligence chief Manuel Callejas y Callejas; Francisco Gordillo Martínez, head of MZ17; and intelligence official Hugo Zaldaña Rojas—guilty of crimes against humanity for the illegal capture and torture of Emma Molina Theissen and sentenced them to twenty-five years in prison. The court also convicted them of aggravated sexual assault, adding eight years to their sentence. Lucas García, Callejas y Callejas, and Zaldaña Rojas were convicted and sentenced to an additional twenty-five years for the forced disappearance of Marco Antonio Molina Theissen. Edilberto Letona Linares, deputy commander of MZ17, was acquitted of all charges. The court ordered the state to implement a series of reparations, including returning Marco Antonio’s remains to his family.Footnote 29

Justice Making: Expanding What Is Possible

The Molina Theissen case expands our notion of what is possible in terms of seeking justice for wartime atrocities. It demonstrates that it is possible to hold the intellectual authors of wartime atrocities accountable, even in extremely hostile contexts. It also demonstrates that it is possible to prosecute wartime sexual violence in domestic courts, a remarkable achievement given the challenges of prosecuting sexual violence in any context. Prosecutors pieced together fragments of evidence, including direct victim and witness testimony, official documents, and expert reports, to determine the chain of command responsibility of the army chief of staff and other senior military officials for these crimes. It marks the first time that the intellectual authors of sexual violence crimes have been convicted in Guatemala, and the first time senior military officials have been convicted for the forced disappearance of a child.

The Molina Theissen case illustrates that human rights prosecutions are not only about punishment. They also have the potential to contribute to the production of new knowledge, or truth, about the recent past, and to the rewriting of the historical narrative of that past, or historical memory. Much of the literature on transitional justice highlights the limits of trials, suggesting their inability to produce larger “truths” about the nature of political violence and repression, in part because of their focus on specific episodes of violence to determine criminal responsibility and in part because of their emphasis on attributing criminal responsibility to the perpetrators (Reference MinowMinow 1998; Reference Rotberg and ThompsonRotberg and Thompson 2000). The Molina Theissen trial not only produced new truths about a specific episode of violence; it also generated greater understanding of general patterns of state-sponsored violence, including the systematic use of torture against detainees and sexual violence against women detainees, the systematic practice of forced disappearance, and the abhorrent practice of targeting the children of dissidents to punish or instill fear. It also drew attention to the estimated five thousand children who were victims of forced disappearance during the armed conflict and the ongoing search of their families for their remains. The Molina Theissen judgment fundamentally challenges the denial narratives that continue to hold currency in contemporary Guatemala, providing tools for the elaboration of new understandings of state-sponsored violence and the rewriting of the historical narrative of Guatemala’s recent past.Footnote 30

Trials may also produce new knowledge about forms of resistance to military rule. Scholars have noted that the human rights language adopted in the context of state-sponsored terror often portrays victims as “innocents,” stripped of any active participation in resistance movements or armed groups, who are then counterposed to state (or other) actors who engage in abuses against them (Reference TheidonTheidon 2006; Reference JelinJelin 2014). This was often an imperative given the highly repressive contexts in Latin America. Trials therefore often center around this binary of innocent victim/guilty perpetrator, obfuscating more complex histories of participation in different forms of resistance or political activism. The Molina Theissen case, originally focused on the forced disappearance of a child who had committed no crime and was involved in no political activity, was constructed on the basis of such assumptions. By joining the case as a complainant, Emma asserted her right to justice, regardless of her political activism. In this sense, the Molina Theissen trial transforms the notion that only certain victims deserve to be heard and to access justice.

No transitional justice measure, trials included, can fully repair the effects of life-altering atrocities such as those recounted here. A trial, even one with a successful conviction, can never undo the trauma that Emma still experiences. She and her family can never fully recover from the irreparable loss of Marco Antonio, exacerbated by the refusal of the perpetrators or the Guatemalan state to return Marco Antonio’s remains. Still, as Emma herself told the court, testifying in court, being heard, demanding justice, has been profoundly reparative. Such is the paradoxical nature of postconflict justice: even a historic victory for accountability such as the Molina Theissen judgment cannot fully repair the harm done. By acknowledging that harm and holding those responsible accountable, however, it provides a remedy that, while incomplete, is wholly necessary.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on field research conducted in Guatemala as a trial monitor for International Justice Monitor, a project of the Open Society Justice Initiative (OSJI). Eric Witte and Taegin Reisman at OSJI provided critical support. I am indebted to Paulo Estrada, my research partner on the Guatemala trial monitoring project, and to the many colleagues and friends who have supported this project with their insights, feedback, and encouragement. I am especially grateful to the Molina Theissen family—Emma Theissen Álvarez de Molina, Emma Molina Theissen, María Eugenia Molina Theissen, and Ana Lucrecia Molina Theissen—whose tenacity, enduring family bond, and love for Marco Antonio are a source of inspiration. This article is dedicated to the memory of Marco Antonio.