1. Introduction

The aim of the article is to review an increasingly popular research domain in publications: teaching and learning a foreign language (FL; L2) in pre-primary schools. The state of the art is very similar to the field of teaching and learning a FL in primary schools: parental intuition and enthusiasm have been driving the growth of interest in such programs despite convincing evidence that early primary programs guarantee no benefits unless certain key conditions are fulfilled. Therefore, in this overview, we examine the evidence publications provide for such FL programs and offer insights into the strengths and conditions of success as well as gaps in the studies indicating weaknesses.

The introduction of the overview states its aims and defines the key terms used in the article (section 1.1), as the terminology and acronyms tend to be confusing. Section 1.2 presents the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and how the database was compiled. The main body of the article comprises five main sections. Section 2 presents theories on how children learn languages and aims to identify the main findings to guide further discussions of empirical studies. Section 3 reviews language policies reflecting typical attitudes (3.1) towards different types of early start L2 programs (3.2), and issues related to the transition to the primary level (3.3). Section 4 analyzes empirical studies on preschool FL programs focusing on children, their parents, and teachers. In section 4.1, we focus on very young learners’ characteristics and the role their individual differences (IDs) play in their L2 development. In section 4.2, we discuss studies on how children's awareness of languages, sounds, and pragmatics are shaped. Section 4.3 examines young FL learners’ morphological and morphosyntactic development, whereas section 4.4 overviews studies inquiring into vocabulary, the most popular research area. Section 4.5 explores empirical research into teachers’ perceptions, beliefs, and professional development (4.5.1) and parents’ roles in the teaching and learning of a new language (4.5.2). Section 4.6 offers insights into preschool classrooms to reveal what goes on in them: 4.6.1 zooms in on classroom discourse; how teachers, other care takers, and children use their first language (L1) and L2 to manage and engage with tasks and negotiate meaning. Studies using ICT are also included (4.6.2). Section 5 discusses how children and other stakeholders have been researched, what methods have been used, how assessment has been applied, how data have been collected and analyzed. The concluding remarks (section 6) synthetize the key findings. We summarize what evidence the studies offer to underpin arguments for the existence of pre-primary FL programs, what the key conditions include, the main outcomes and challenges, and where further research is needed. The list of questions arising from the overview offers guidance for future studies.

This text is complemented by Supplementary Appendix Table S1. In this table, the most important characteristics of all empirical studies mentioned are presented following the same criteria: authors’ names, and year of publication, purpose of study or research questions, research design, contexts in which the project was implemented, participants, data collection instruments, and main findings. We hope the two documents give readers as full a picture as possible.

1.1 Clarification of terminology

The terms used in this article need to be clarified. The terminology in some publications is misleading; therefore, we need to state how we distinguish programs, what is included and what is not. As a starting point, we use the terms preschool, pre-primary, early start, and very young learners as synonyms. As for the children's age, we analyzed publications on FL programs for children between the ages of two to six in kindergartens and preschools in early childhood education and care (ECEC) as part of an organized program in public and private sectors. We included L2 programs implemented in contexts where the target language is not an official language and the time allocated to the additional language is less than 30% in the curriculum (Johnstone, Reference Johnstone and Johnstone2010; Nikolov & Timpe-Laughlin, Reference Nikolov and Timpe-Laughlin2021, p. 2). We use the terms foreign, additional, and second language (L2) interchangeably within these boundaries. Studies on programs defined as content and language integrated learning (CLIL, Cenoz, Reference Cenoz2015) or bilingual or heritage languages were considered carefully to decide whether they can be characterized as a FL or a partial or a full immersion program (Turnbull, Reference Turnbull2018). Full immersion, bilingual or L2 programs, and home schooling are not included.

1.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The database comprises language policy documents (section 3), books, chapters in edited volumes, and articles in refereed journals. It includes publications from around the globe (unevenly distributed, though), written in English, not only on the teaching and learning of English, the most popular focus, but also on other additional languages. The empirical studies were published between 2000 and 2022. Unpublished theses, research reports, and studies not sharing enough information to make them replicable (e.g., what specific tasks or tests were used and how) or credible (by using thick description, member checking, and triangulation, of multiple independent methods of collecting data to arrive at the same results) (Creswell, Reference Creswell2012, pp. 259–260; Mackey & Gass, Reference Mackey and Gass2016, p. 233) were not included.

The dataset was compiled by searching the internet iteratively, using the following key words in various (and/or) combinations in the Core Collection of Web of Science, EBSCO, and Google Scholar: very young language learner, early childhood, foreign language teaching, learning in early years, kindergarten, preschool, pre-primary, daycare, bilingual program, early foreign language education program, and policy. The languages included in the search were Chinese, English, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Russian, and Spanish. Additionally, we contacted the Goethe Institute and the Confucius Institute, and colleagues researching early language programs for information, and checked references in the publications. All studies in the database chosen for the review were published in refereed journals and in books. In the first round in 2021, we found thousands of entries; we narrowed down the dataset by reading the abstracts first, and deleted publications not meeting the inclusion criteria. This search resulted in 70 studies that we read closely and included in our first draft. Additional searches in January, August, and October 2022 and recommendations from reviewers of the first draft resulted in an additional 15 publications. After reading all complete texts again, we included 74 empirical studies (see Supplementary Appendix Table S1). We found one replication study (Ferjan Ramírez et al., Reference Ferjan Ramírez, Sheth and Kuhl2021), no evaluation study of a complete program (e.g., Dobson et al., Reference Dobson, Pérez Murillo and Johnstone2010), but one baseline study (British Council/Nile, 2017) that explored the feasibility of introducing English at the pre-primary level in Peru.

Out of the 74 studies shown in Figure 1, five were published between 2001–2010, nine between 2011–2013, and the peak in publications – 24 studies – was between 2014 and 2016. Similar numbers are shown in the periods between 2017–2019 and 2020–2022: 19 and 18, respectively. These numbers in the graph indicate a dynamic increase in published research on pre-primary FL learning in recent years.

Figure 1. The distribution of 74 publications between 2001 and 2022

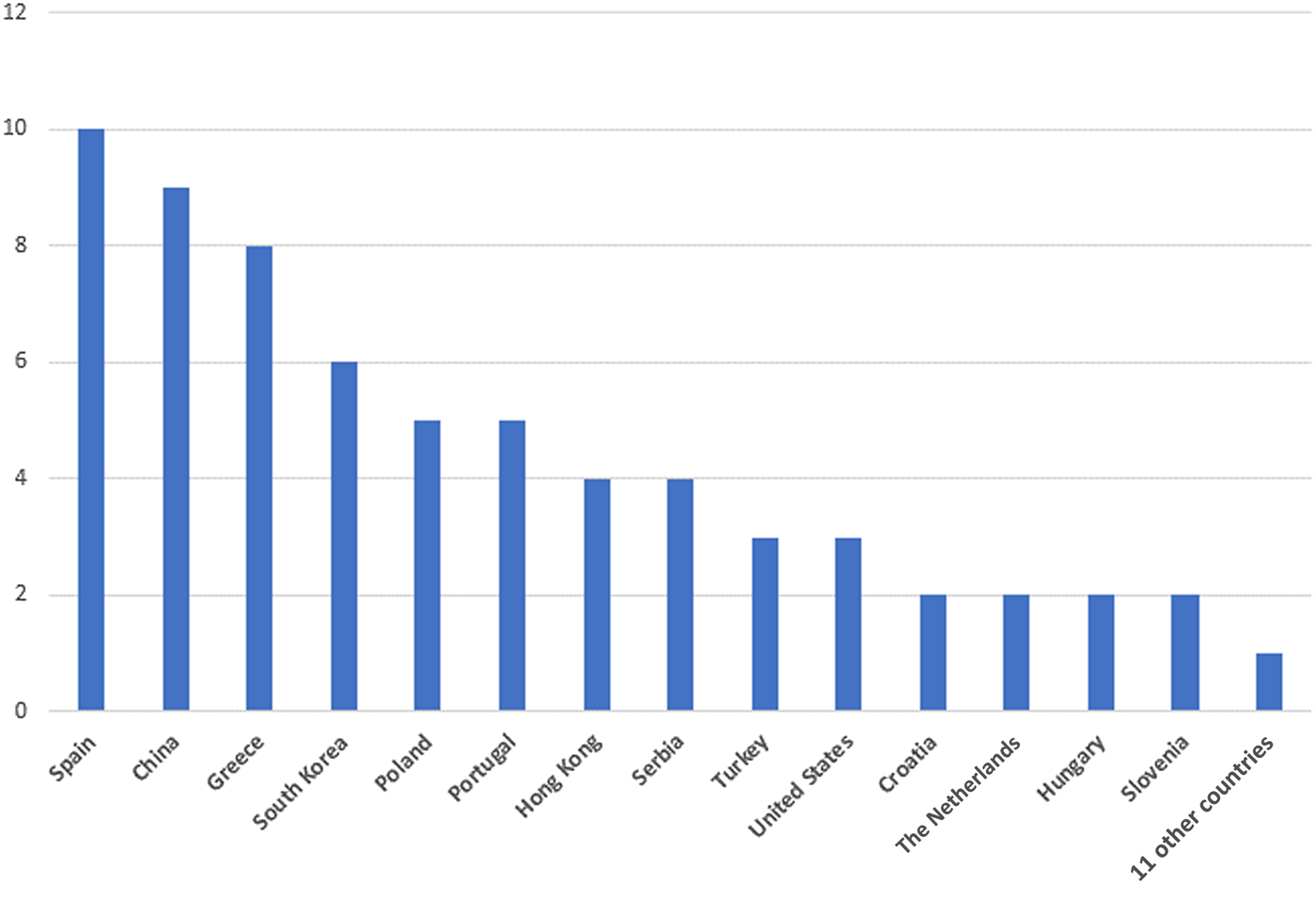

Figure 2 shows the geographic distribution of 25 countries where researchers collected data. The distribution of papers shows that pre-primary FL programs are more popular among researchers in some countries than in others. These findings, however, do not indicate how widely spread pre-primary programs are in these countries. Ten papers were found on contexts in Spain, nine on China, eight on Greece, six on South Korea, five on Poland and Portugal, four on Hong Kong and Serbia, three on Turkey and the United States, two on Croatia, Hungary, Netherlands, and Slovenia, and one on Argentina, Cyprus, Egypt, England, France, Germany, Honduras, Macau, Norway, Slovakia, and Sweden.

Figure 2. The distribution of 74 publications conducted in contexts in 25 countries

2. Theories on how children learn languages in bilingual and FL contexts

A short summary of theories we found in the literature on how children learn languages in L1, FL, and L2 contexts is necessary so that we can use the main findings authors claim are conducive for children to be successful in learning a new language in pre-primary programs. Three approaches are typical in theories on how children learn additional languages: they focus on similarities and differences between: (1) first and additional language learning, (2) young children, adolescents, and adults, and (3) contextual variables (including input, opportunities for interaction in L2 and L1, time, teachers’ proficiency, etc. which vary in contexts), and how these impact children's development. Although it may be challenging to see the common denominators across contexts in which children learn languages, a range of recent publications have synthetized key findings. Many authors focus on common characteristics (e.g., Bialystok, Reference Bialystok2018; Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Zhao, Shin, Wu, Su, Burgess-Brigham, Gezer and Snow2012; Johnstone, Reference Johnstone, Enever, Moon and Raman2009; Murphy, Reference Murphy2014; Nikolov, Reference Nikolov and Nikolov2009; Schwartz, Reference Schwartz2018; Turnbull, Reference Turnbull2018), whereas others emphasize variability (Birdsong, Reference Birdsong2018; Bylund et al., Reference Bylund, Hyltenstam and Abrahamsson2021; Nikolov & Mihaljević Djigunović, Reference Nikolov and Mihaljević Djigunović2006, Reference Nikolov and Mihaljević Djigunović2011, Reference Nikolov, Mihaljević Djigunović and Gao2019) depending on how they frame discussions.

As for the age-related similarities between L1 and L2 learning, authors tend to agree that the younger children are, the more they rely on implicit learning characterizing L1 acquisition. Children can memorize words, unanalyzed chunks, and, gradually, first comprehend and later produce them in specific contexts relying on their procedural knowledge. Explicit analytical learning becomes available over the years, but not typically before puberty. It contributes to declarative knowledge characterizing adolescents’ and adults’ learning, but rarely children between the ages of two and six developing in their languages. There are important IDs even at a young age in the extent to which children are aware of rules, strategies, and their own learning.

As far as the rate of learning is concerned, the younger learners are, the slower they develop in their additional language. Oliver and Nguyen (Reference Oliver, Nguyen, Oliver and Nguyen2018) used metaphors of the tortoise and the hare to characterize child and adult learners: although children are slower at the beginning, in the long run they may be more successful than adults. For this to happen, children need optimal amount and quality of input they can comprehend, and opportunities to experience meaning making and output, and to interact in the target language over a long period of time.

Discussions about a critical or sensitive period for language learning have concluded that maturational constraints tend to be limited to accent and do not impact other language domains. As most teachers in early years FL programs are English as lingua franca users, few can serve as authentic models. Their accent will impact what children can do over time. It is unrealistic to expect native-like proficiency beyond that of the teachers in contexts where children rely on input offered overwhelmingly by their teachers and peers.

Contexts in which children learn vary in the source, amount, and quality of input and learning opportunities. In contexts where the studies included in this article were conducted, children were exposed to a limited amount of L2 input (in 5–10% of the time in the curriculum, which can range between a few minutes per day, to one or two hours a week; see Johnstone, Reference Johnstone and Johnstone2010; Nikolov & Timpe-Laughlin, Reference Nikolov and Timpe-Laughlin2021, p. 2). An additional point concerns the quality of the input: the source of L2 is overwhelmingly the teacher, who may be insecure about their own L2 and age-appropriate pedagogical competences. Therefore, realistic expectations need to be defined carefully, as the results of empirical studies presented in sections 4.2–4.4, 4.6, and 5.2 will show.

These points have important implications for language pedagogy. Children learn languages best when they participate in intrinsically motivating, age-appropriate, meaning-focused activities in relaxed child-friendly contexts in interaction with their peers and teachers. In highly context-embedded and familiar tasks when input is tuned to what they can comprehend, children can figure out meaning by relying on their background knowledge of the world and scaffolding offered by teachers and other children. They need and tend to enjoy a lot of varied and playful practice. Classroom routine, storytelling, songs and rhymes, and playful engaging tasks involving movement can all offer learning opportunities without inducing anxiety.

Thus, there are important lessons learnt from how children develop in their L1 (e.g., Rowe & Snow, Reference Rowe and Snow2020) and English as L2 (e.g., Buysse et al., Reference Buysse, Peisner-Feinberg, Páez, Hammer and Knowles2014; Washington-Nortey et al., Reference Washington-Nortey, Zhang and Xu2020), as well as from recent reviews on early preschool FL programs (e.g., Garton & Copland, Reference Garton and Copland2019; Nikolov & Lugossy, Reference Nikolov, Lugossy and Schwartz2022; Thieme et al., Reference Thieme, Hanekamp, Andringa, Verhagen and Kuiken2021) and how children are assessed (Nikolov & Timpe-Laughlin, Reference Nikolov and Timpe-Laughlin2021; Prošić-Santovac & Rixon, Reference Prošić-Santovac and Rixon2019). Publications for teachers on how to implement good practice in pre-primary classrooms are also widely available (Curtain & Dahlberg, Reference Curtain and Dahlberg2016; Bland, Reference Bland2015; Ghosn, Reference Ghosn, Coombe and Khan2015; Mourão, Reference Mourão and Bland2015a; Mourão & Ellis, Reference Mourão and Ellis2020; Mourão & Lourenço, Reference Mourāo and Lourenço2015; Murphy, Reference Murphy2014; Murphy & Evangelou, Reference Murphy and Evangelou2016; Pinter, Reference Pinter2006, Reference Pinter2011; Rokita-Jaśkow & Ellis, Reference Rokita-Jaśkow and Ellis2019; Schwartz, Reference Schwartz2018, Reference Schwartz and Schwartz2022; Widlok et al., Reference Widlok, Petravić, Org and Romcea2011).

3. Language policy documents on preschool FL teaching and learning

By the late 1990s, when primary FL programs took center stage (Johnstone, Reference Johnstone, Garton and Copland2019), European language policy documents included pre-primary school children among the target groups before such programs were widely available. The first overview (Blondin et al., Reference Blondin, Candelier, Edelenbos, Johnstone, Kubanek-German and Taeschner1998) offered insights into research on foreign language education in primary and preschools in the European Union. In 2006, the European Commission published a report (Edelenbos et al., Reference Edelenbos, Johnstone and Kubanek2006) synthetizing the most important research-based pedagogical principles of teaching languages to very young learners. A policy handbook published also by the European Commission (2011) outlined how language learning at the pre-primary school level can be made efficient and sustainable and promoted FL programs in pre-primary institutions. In the United States, the American Councils for International Education (2017) reported findings of a K-12 foreign language enrollment survey. In most contexts, early FL learning, overwhelmingly English, was offered following parental interest and pressure (e.g., in 16 European countries and Australia, Hong Kong, Canada, and USA: Nikolov & Curtain, Reference Nikolov and Curtain2000; in Portugal: Mourão, Reference Mourão, Garton and Copland2019). This trend energized “English fever” (in Indonesia: Kiaer et al., Reference Kiaer, Morgan-Brown and Choi2021) and “Englishization” (in the Netherlands: Keydeniers et al., Reference Keydeniers, Aalberse, Andringa and Kuiken2021). In South America, and on other continents, early English learning is seen as a means of “opening doors” (Sayer, Reference Sayer2018). A key issue in languages policies concerns the dominance of English and the lack of emphasis on other modern languages - apart from those learned in English-speaking countries.

Other areas policy makers need to bear in mind, according to Johnstone (Reference Johnstone, Garton and Copland2019), include long-term planning of provision, including teacher development, continuity and transfer between pre-primary and primary, how small-scale innovative projects can be generalized to the larger population, and international collaboration in cross-disciplinary projects.

Realistic aims for pre-primary FL curricula include developing children's interest in and favorable attitudes towards the target language, uses of prefabricated chunks, and some language awareness (Johnstone, Reference Johnstone, Garton and Copland2019). All these are to be aligned to the curricular aims of pre-primary institutions in specific contexts. What policies and curricula aim for, however, may be different in practice: teachers may distort or enhance policies (Hamilton, 1990, cited by Johnstone, Reference Johnstone, Garton and Copland2019, p. 17), as they implement what experts designed. Although, for example, the European Commission (2011, p. 17) states that children “should be exposed to the target language in meaningful and, if possible, authentic settings, in such a way that the language is spontaneously acquired rather than consciously learnt”, this idea can be interpreted in many ways, as some empirical studies show.

Language policies and studies on pre-primary FL projects frame their ideas enthusiastically (e.g., Alexiou, Reference Alexiou, Zoghbor and Alexiou2020); few sources discuss backlashes. For example, in Indonesia, English was “abolished” from its primary curriculum owing to lack of trained teachers and policy makers’ worrying “about the English culture that might be imparted and engaged to the learners” (Azmy, Reference Azmy2020, p. 53). In Germany, starting English may be postponed from Year 1 to 3 also owing to shortage of teachers as well as to discouraging test results (Wilden & Porsch, Reference Wilden and Porsch2020). In sum, language policy documents are highly supportive and optimistic about pre-primary FL learning; however, they tend to lack details as to how and in what conditions such programs should be implemented.

3.1 Public attitudes towards an early start of FL learning

Overall, most publications on pre-primary FL programs document enthusiasm (Ioannou-Georgio, Reference Ioannou-Georgiou, Mourāo and Lourenço2015), especially on the part of parents (e.g., Mourão, Reference Mourão, Garton and Copland2019). Their favorable attitudes towards early start programs are responsible for the mushrooming of pre-primary English programs in Europe, Asia, South America, and other places. Parents tend to believe that early stimulation is conducive to learning English and the earlier their offspring starts, the better they will be over time. Parental pressure can, therefore, oblige preschools to offer such courses to meet these expectations. Decision makers tend to accede to these demands although teacher shortage is often an issue. The dynamics play out in specific contexts in different ways. In South Korea, for example, Kiaer et al. (Reference Kiaer, Morgan-Brown and Choi2021) found positive relationships between how much English was used in two types of kindergarten programs and the children's level of anxiety. Parents with higher ambitions placed their children in more intensive (immersion-like) programs. The children tended to be more anxious than their peers in programs with less exposure to and insistence on “English only”. In Poland, Rokita-Jaśkow (Reference Rokita-Jaśkow2013, Reference Rokita-Jaśkow2015) also revealed a complex picture resulting from interactions across parents’ aspirations, their choice of public or private preschools, English teachers’ beliefs and competences, and differences in children's learning opportunities. Parents’ previous language learning experiences impacted their decisions as to how early they wanted their offspring to start English and in what program: the less successful as L2 learners the parents themselves were, the more they believed in earlier and more intensive programs (Rokita-Jaśkow, Reference Rokita-Jaśkow2015).

3.2 Pre-primary programs

Despite the large number of publications on early FL teaching and learning, little is known about preschool programs. As the headings in this review on the emerging themes in studies indicate, authors offered many insights into narrow aspects, but we found no program evaluation or studies offering a clear picture of what the curricular aims were, how and to what extent they were achieved based on criteria. Owing to these reasons, few studies are replicable or offer details of programs for adoption. Some examples of good practice were found. For example, valuable documents are shared by the Goethe Institut on early German as a FL: detailed recommendations as to how programs should be organized (Widlok et al., Reference Widlok, Petravić, Org and Romcea2011) and freely available age-appropriate teaching materials can be downloaded from their websites (https://www.goethe.de/ins/au/en/spr/unt/kum/dfk/fuf.html; https://www.goethe.de/ins/pl/de/spr/unt/kum/dfk/dms.html). No empirical study was, however, found on how early German or other L2 programs work over time.

A few publications compare children's development in immersion and FL programs (e.g., Kiaer et al., Reference Kiaer, Morgan-Brown and Choi2021). Others offer insights into projects aiming to raise children's awareness of additional languages (e.g., Lourenço & Andrade, Reference Lourenço and Andrade2013), and examine how children's attitudes to English and their grades were impacted by preschool programs (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhao, de Ruiter, Zhou and Huang2020). Such studies are discussed under the specific focal points below, but first we present problems related to transition from pre-primary to primary school.

3.3. Transition issues

Preschool education has created a new transition in children's lives. The need to investigate transitional processes is often stressed (e.g., Nikolov, Reference Nikolov and Nikolov2009), but such studies are still rare. This early transition occurs at different learner ages and raises issues at different levels, which are solved in different ways in different contexts (OECD, 2017). General educational projects (e.g., Carida, Reference Carida2011; O'Kane, Reference O'Kane2016) call for national transition policies, cooperation between preschools and primary schools, introduction of children's portfolios with information on their transition experiences, and suggest that widespread problems of inconsistency and discontinuity can be solved only by involving all stakeholders.

In the FL education field, problems in the preschool to primary school transition emerge in domains of FL policies, school and curriculum, classroom, teacher, parents, and young learners themselves (Mihaljević Djigunović & Letica Krevelj, Reference Mihaljević Djigunović, Letica Krevelj and Schwartz2022). European documents (e.g., European Commission, 2011) emphasize the key importance of continuity and coherence. However, there are many challenges regarding these. In some contexts (e.g., parts of Germany, Estonia), securing continuity may be difficult because the FL learnt in preschool may not be offered in a particular primary school, or it may not be offered from primary grade one (European Commission, 2017).

Coherence, too, often emerges as a problem where teaching approaches at the two levels are not consistent and logical to children. Suggested ways of ensuring coherence are structural integration (with preschool and primary school as part of the same educational unit), conceptual integration (basing the two curricula on consistent knowledge and values) and parent–teacher partnership integration.

McElwee (Reference McElwee, Mourão and Lourenço2015) found that preschool learners of French in England, who were exposed to the Narrative Format teaching approach using a series of stories focusing on children's common experiences, developed language learning strategies that led to higher metalinguistic awareness in grade three of primary school; such level of awareness was very rare in FL beginners at that age. He concluded that introducing FL at preprimary could secure continuity and progression during transitioning to primary school. A Chinese study (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhao, de Ruiter, Zhou and Huang2020) into effects of preschool English as a foreign language (EFL) on achievement and attitudes to EFL and L1 Chinese in primary grades one and three found a positive relationship between the included variables. In their comparative study of Croatian primary EFL learners who had learned EFL at preschool and joined classmates who were total beginners, Letica Krevelj and Mihaljević Djigunović (Reference Letica Krevelj and Mihaljević Djigunović2021) found that their attitudes and motivation differed. While the EFL teacher was the main motivator in the case of total beginners, this was not the case for non-beginners: in their case the teacher's motivating role was less prominent and they were more motivated by a sense of progress. However, some non-beginners reported being demotivated by the mismatch of their self-perceived EFL proficiency and the input they were exposed to in the primary classroom.

Understanding the complexity of the pre-primary to primary transition in FL learning requires both extensive and in-depth study. A recently proposed research framework (Mihaljević Djigunović & Letica Krevelj, Reference Mihaljević Djigunović, Letica Krevelj and Schwartz2022, p. 632) involves all participating actors and their interactions, includes both macro and micro aspects, and is nested in the social context where transition is taking place. The framework implies that transition begins before children leave preschool and ends when they have settled in their new environment, which means that its duration may be different for different children.

4. Empirical studies on preschool FL programs

4.1. Children's individual differences

Research suggests that preschoolers differ in many characteristics impacting FL learning behavior and achievements. Some IDs play a more crucial role in preschool FL learning than in the case of older learners. One such ID is temperament (mood, adaptability, level of responsiveness). Positive mood, higher levels of adaptation, activity, and initial reactions were found to correlate with a greater number of verbal and non-verbal reactions of Chinese EFL preschool learners; negative mood coupled with lower number of initial reactions was observed to cause teachers’ misinterpretation of children's needs, which then negatively affected learner motivation and incidental learning (Sun et al., Reference Sun, de Bot and Steinkrauss2015a, Reference Sun, Steinkrauss, Tendeiro and de Bot2015b).

Aptitude emerged as an important ID in vocabulary and grammar acquisition. Greek young learners’ scores on vocabulary tests varied significantly depending on their cognitive (analytic reasoning ability, short term memory) and phonological skills (phonetic repetition, distinction of non-words) (Alexiou, Reference Alexiou and Nikolov2009). Chinese preschool learners’ phonological short-term working memory was found to be a significant predictor of their vocabulary scores (Unsworth et al., Reference Unsworth, Persson, Prins and de Bot2014). Analytical reasoning correlated with receptive grammar, while short-term memory correlated with productive vocabulary learning (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Steinkrauss, van der Steen, Cox and de Bot2016).

Motivation is a key factor in FL learning. Preschoolers’ motivation is based on their positive attitudes to FL (Griva & Sivropoulou, Reference Griva and Sivropoulou2009), their FL teacher (Ahn & West, Reference Ahn and West2018), and they are influenced by their parents and peers (Jin et al., Reference Jin, Zhou, Hu, Yang, Sun and Zhao2016). Children are intrinsically motivated for FL learning. Maintaining their intrinsic motivation calls for a predictable learning environment, moderately challenging tasks, instructional support, assessment focusing on self-improvement, and learner autonomy in deciding on FL content and outcomes (Wu, Reference Wu2003). Pre-primary FL learners can develop self-motivation if their teacher fosters their self-esteem, self-confidence, co-operation with other learners, and praises their efforts (Brumen, Reference Brumen2011).

Vičević Ivanović et al. (Reference Vićević Ivanović, Košuta and Patekar2021) studied FL learning strategies of Croatian very young learners of French, German, and Italian. They used the projection technique to elicit information on children's strategies: children were asked how they would help their plush toy to say particular words and structures in the L2 (e.g., How would you help the elephant to learn to say ‘der Apfel’?). The findings pointed to high frequency of memory (e.g., model repetition, listening to the interlocutor) and informal strategies (e.g., showing and naming the object, exposure to media). Frequency of some of the identified strategies varied with the intensity of the participants’ FL exposure; thus, children with a more intensive L2 exposure tended to use informal strategies (learning through songs and rhymes) and social strategies (contact with a native speaker). Some formal strategies (e.g., learning by drawing or writing words) were not connected with intensity of L2 exposure.

When the importance of positive learner attitudes and motivation is ignored, children may develop FL anxiety. Insistence on rote memorization or native speaker pronunciation are some of the sources of preschool EFL learners’ anxiety found in the Korean context (Kiaer et al., Reference Kiaer, Morgan-Brown and Choi2021). Using age-appropriate teaching practices and developing FL enjoyment are suggested as ways of creating anxiety-free classrooms. In another example on low anxiety, kindergarten children were assessed with a puppet theatre twice a year in Serbia (Prošić-Santovac & Navratil, Reference Prošić-Santovac, Navratil, Prošić-Santovac and Rixon2019). Analyzing videotaped observations and interviews, the authors found that children happily engaged in the tasks administered in English and Serbian, they were not anxious, and were willing to interact. How the children performed the tasks in English was not analyzed; thus, it is unclear how detailed, valid, and reliable the assessments were.

Findings on family socio-economic status (SES) indicate that SES is both a mediating cognitive factor (securing access to FL learning resources) and a mediating affective factor (through parental involvement and encouragement) (Rokita-Jaśkow, Reference Rokita-Jaśkow2013). SES emerged as a good predictor of productive vocabulary development (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Steinkrauss, van der Steen, Cox and de Bot2016); however, SES did not play a key role in studies on the youngest age group (Ferjan Ramírez et al., Reference Ferjan Ramírez, Sheth and Kuhl2021).

4.2. Children developing awareness about language, sounds, and pragmatics

Studies on preschool FL learners’ perception of the new language they are learning focused on phonological, phonemic, and pragmatic awareness. Kearney and Ahn (Reference Kearney and Ahn2013) studied children engaging with multiple languages (Chinese, Korean, and Spanish) in minimal input preschool classrooms in the United States. They observed how children's language awareness developed in teacher-led lexically focused activities. Kearney and Barbour (Reference Kearney and Barbour2015) used a socialization approach: they observed how children became aware of languages different from their own, how they related to and joined activities, and how they saw themselves as children who knew a few words in multiple languages. In other words, they documented how children started on the journey of becoming language learners by participating in, thereby socializing into, language-related activities. The authors analyzed how children's language awareness developed through engagement with the three languages, and they documented their non-linear process of developing awareness and acceptance of differences and diversity in languages.

In their experimental study, Lourenço and Andrade (Reference Lourenço and Andrade2013) used the ‘awakening to languages approach’ (exposing children to a variety of languages to discover and explore new sounds and writing systems) with Portuguese children (age three–six) and found that the approach helped increase preschoolers’ phonological awareness in their L1: the children developed interest in observing and reflecting about sounds and language. Being able to think about and analyze units of speech in L1 is considered a steppingstone for successful development of vocabulary, reading, and writing in a FL, too.

Phonemic awareness was the focus of a study by Martinez et al. (Reference Martinez, Coyle, De Larios, Murphy and Evangelou2015), in which they tested effects of explicit instruction of English sibilant phonemes on Spanish preschoolers. Their findings showed a positive effect of explicit phonics teaching. Interestingly, using actions accompanying pronunciation of included words in the experimental group did not lead to higher acquisition of the sibilants. The authors suggest that actions need to be linked to the sounds in an explicit and unambiguous way to be a good enough support. Immigrant children for whom English was a third language were more successful than Spanish L1 children: their larger experience of L2 learning raised their phonemic awareness.

Portóles Falomir (Reference Portóles Falomir2015) investigated pragmatic awareness of preschool and primary school children in Spain who were learning Catalan, Spanish, and EFL. She found that by the age of four these multilingual preschoolers had already developed a certain level of pragmatic awareness (though lower than primary school learners). Their pragmatic awareness was not connected to language proficiency in any particular language, but to their multilingual proficiency (comprising interaction of the three language systems, cross-linguistic interaction, and the specific linguistic and cognitive skills exclusive to multilingual learning).

4.3. The acquisition of L2 morphological and morphosyntactic elements

Morphological and morphosyntactic studies focusing on preprimary FL learners are rather rare; only two publications examined these areas. Hillyard (Reference Hillyard, Murphy and Evangelou2015) carried out an action research project with four-year-old EFL learners in Argentina. Her aim was to see if using rhythmic patterns in stories would help her learners acquire and use correctly word order of adjective + noun constructions, which cause interference with Spanish word order. The four stories used in the project involved both rhythmic patterns and pictures, or only one of them, or none. The findings showed that the higher number of correct word order was related to stories which did not include rhythmic patterns. The author attributed this finding to the stronger impact of substituting vocabulary, personalizing the story and using language creatively.

McElwee (Reference McElwee, Mourão and Lourenço2015) investigated effects of using short narratives in teaching French to preschoolers in England. His findings showed that after listening to and watching stories, the participants were generally able to produce very short sentences and phrases, and that everyone produced more complete than incomplete utterances. Overall, the young learners’ morphosyntactic knowledge and skill became more sophisticated with increasing learner age as a result of working with stories in French.

4.4 Studies on vocabulary development

In very early FL learning, vocabulary is often considered as the foundation of children's FL competence in line with theories (see section 2). In this section, we overview what aspects of vocabulary studies have been inquired into. Focusing on lexical development of preschool EFL learners (age range 1; four–five years), Rokita (Reference Rokita2007) carried out two extensive studies, a longitudinal one and a cross-sectional one. Her longitudinal findings showed that Polish preschoolers could learn not more than 200 words in English during a two-year period, their vocabulary reflected the input they had been exposed to, and what they knew was unstable and prone to fast forgetting. Based on the cross-sectional data, the author suggested there might be a threshold of FL lexical knowledge that facilitates acquisition of further items. Four-year-olds progressed significantly faster than younger learners, and Rokita attributed this to their larger short-term memory capacity. The production level of all preschoolers was characterized by mechanical use of items learned in class, with children who had learned longer incorporating EFL words in L1 utterances. Spontaneous or creative use of single words or formulaic expressions was extremely rare. Best performances were related to high and persistent parental involvement in children's preschool FL learning in the form of, for example, practicing words and reading at home.

A study on Spanish children focused on which activities contribute to vocabulary knowledge. Albaladejo Albaladejo et al. (Reference Albaladejo Albaladejo, Coyle and de Larios2018) inquired into the benefits of stories, songs, and a combination of the two for vocabulary learning by preschool EFL learners (aged two–three). They found that stories were the most and songs the least conducive to vocabulary development and that the children who behaved in a ‘quietly attentive’ manner during the activities performed best.

Drawing attention to a methodological concern in studies claiming that songs contribute to vocabulary acquisition, Davis and Fan (Reference Davis and Fan2016) remarked that such studies do not include true control groups against which to compare results. Thus, their study involved three EFL classes of Chinese preschoolers aged four–five years. They were exposed to 15 selected vocabulary items with five out of the 15 items in each of the three conditions: song, choral repetition, or neither of the two as a control condition. The authors concluded that both songs and choral repetition have important pedagogical value in preschool children's FL vocabulary acquisition.

Authentic cartoons were used in two projects in Greece. Greek children's implicit vocabulary uptake of 21 nouns, including cognates, was assessed after watching four episodes of the popular British cartoon series Peppa Pig multiple times over a month followed by discussions in their mother tongue (Alexiou, Reference Alexiou, Gitsaki and Alexiou2015). Peppa Pig used slow, clear, child-directed speech and was easy to follow. Children could recall about half of the words, indicating that implicit learning worked well in highly contextualized age-appropriate activities in which meaning-making was supported both visually and in L1.

Explicit versus implicit teaching effects were the focus of Kokla's (Reference Kokla and Alexiou2021) experimental study with Greek preschool EFL learners. All children watched episodes of the Peppa Pig cartoon. The control group was tested after viewing, while the experimental group received instruction after viewing and was then tested on formulaic language used in the cartoon. The findings indicated that mere viewing was beneficial and raised the control group preschoolers’ test results. The even higher scores in the experimental group proved that explicit teaching of formulaic expressions reinforced their learning.

Yeung et al. (Reference Yeung, Ng and Qiao2020) compared effects of implicit and explicit teaching of EFL vocabulary and phonemic awareness on Chinese children between the ages of four and six in Hong Kong. The findings of their experimental study showed that explicit vocabulary teaching was more effective than implicit instruction in acquiring both productive and receptive vocabulary, with a stronger effect on productive vocabulary. They attributed the impact of explicit vocabulary teaching to learners’ increased attention and engagement with the target words. Applying a CLIL-inspired pedagogic approach to teaching EFL to Portuguese preschoolers aged three–five years, Lucas et al. (Reference Lucas, Hood and Coyle2020) found the approach extremely useful for acquiring both receptive and productive vocabulary. The project children were consistently successful at contextualized word production and were very motivated to learn how to write the words learned.

Looking into the potential of task-related physical activity and gestures for promoting vocabulary learning in preschool children, Toumpaniari et al. (Reference Toumpaniari, Loyens, Myrto-Foteini Mavilidi and Paas2015) carried out an experimental study with four-year-old Greek learners of EFL. Three learning conditions were examined: learning vocabulary without physical activity or gestures, learning with gestures only, and learning with both gestures and physical activity. The results of the study showed that a combination of task-related physical activity and gestures during vocabulary learning was related to the highest learning outcomes.

An important emerging topic awaiting systematic research concerns measuring the process and results of preschoolers’ FL vocabulary learning over time. In most of the above studies, the amount of vocabulary the children were able to comprehend or produce was very small. The reason that so many studies in the dataset want to quantify outcomes indicates that researchers think in terms of models characterizing older learners: they want to measure how many words children can comprehend and use actively, but the outcomes are very modest, indicating the slow progress children make (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Steinkrauss, Wieling and de Bot2018; Yeung et al, Reference Yeung, Ng and King2016).

4.5. Research on FL teachers and parents

A range of studies have examined perceptions and beliefs of pre-service trainee teachers of FLs as well as practicing preschool FL teachers about teaching very young learners (YLs) and how children define the good language teacher. Who would be best equipped to teach FLs to very YLs, FL specialist teachers or pre-primary practitioners, native speaker teachers or non-native speaker teachers, are also recurring topics. The section ends by considering FL teachers’ interactions with learners and parents as well as key challenges in teacher education.

4.5.1 Studies on teachers

Studies on FL teachers to preschool learners focus on their profiles, the competences they should have, on programs that lead to the desired competences, and ways of filling the gap between the demand and supply of qualified teachers for this age group. Studies involved pre-service and in-service teachers.

Portiková (Reference Portiková, Mourão and Lourenço2015) investigated FL teaching in Slovakian preschools (state, private, and church-funded). She collected data using questionnaires, classroom observation, and interviews. Her findings pointed to problems of shortage of qualified FL teachers and a generally non-systematic approach to provision as well as assessment of teaching conditions. As in many other contexts, preschool FL teaching in Slovakia is often organized under parents’ pressure and with key stakeholders not knowing about basic principles of FL teaching and learning at the preschool age.

Dikilitaş and Mumford (Reference Dikilitaş and Mumford2020) carried out a longitudinal qualitative study involving three EFL teachers working as bilingual education teachers in a private kindergarten in Turkey. The authors investigated the changes in practice emerging after a nine-month in-service training course and as a result of their bilingual teaching experience. Analysis of data collected by teacher logs, written interviews, and observation notes indicated that they developed bilingual education teacher competences by taking on the pedagogue, interactive communicator, and translanguaging facilitator roles. The study points out that those teaching preschool learners need to be able to take on roles other than those of FL teachers.

Dagarin Fojkar and Skubić (Reference Dagarin Fojkar and Skubic2017) inquired into pre-service preschool teachers’ beliefs about teaching FLs to very YLs. Their questionnaire-based study of Slovenian preschool teachers revealed that they held positive beliefs about FL learning. They believed that FL teaching to preschoolers should be done using game-like activities, stories, and songs and that knowledge of FL teaching methodology was the most important competence that preschool FL teachers should have. Additionally, younger trainees in the study believed more strongly that high FL proficiency was very important, while older trainees held stronger beliefs about the importance of knowing more than one language.

Sixty pre-service female teachers participated in a study conducted in Macau (Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Liu, Ha, Zhang and Ding2021). Their reflective papers written over a semester documented changes in their beliefs as a result of what they learnt and experienced in microteachings and observations. They developed new beliefs about teaching preschool children and their beliefs became more concrete and concerned age-specific criteria related to designing activities and materials and assessments.

Waddington (Reference Waddington2021) analyzed the impact of a FL teacher training program embedded as an innovation in the early childhood degree program at a Spanish university. Based on analysis of data collected by questionnaires and focus group discussions administered before and after the course, she found that participants’ initial preferences for FL native speakers and FL specialists as ideal FL teachers to preschoolers changed by the end of the program. Participants became aware of certain discriminatory and deficit beliefs implied in their initial stereotypical views and realized that they could develop linguistically over time.

Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Li and Yeung2022) analyzed datasets collected in videotaped classroom observations and stimulated recalls from two novice teachers at private kindergartens in China to explore how their language awareness and pedagogical content knowledge impacted their practice. They found that both teachers used a product-oriented, teacher-dominated “no Chinese” approach, and drilled language items extensively, clearly not in line with good practice.

Prošić-Santovac and Radović (Reference Prošić-Santovac and Radović2018a) focused on three stakeholders: they investigated how preschoolers, their teachers, and parents exercised their agencies in the case of a teaching model that was based on strict separation of L1 and L2. Their findings indicate that the model restricted both the teachers’ and parents’ autonomy, while the preschoolers regularly initiated communication with their L2 teacher in L1 and resorted to translation. Teachers and parents focused on exercising their agency through influencing the children's motivation to be successful in their L2 learning.

Finally, how teachers collaborate was explored in two studies with different outcomes. Experiences of pre-service EFL teachers who taught two sessions in a Turkish kindergarten were analyzed by Bekleyen (Reference Bekleyen2011). Data from interviews with the teachers and their written reflections on the experience showed that this short teaching practice enabled them to learn how to prepare lesson plans and use them in a real classroom context, how to teach in collaboration with co-teachers, and how to self-reflect critically on their teaching. Collaboration between a native speaker teacher and three non-native speaker teachers of English was the focus of a case study carried out in a kindergarten in Hong Kong (Ng, Reference Ng2015). Many obstacles to effective collaboration emerged at the levels of pedagogy and logistics as well as at the personal level preventing the non-native teachers from benefiting from the project. This publication is exceptional in that it reports how a well-designed developmental project was not feasible and why it failed. The author suggested ways in which more effective collaboration would be possible.

In sum, these mostly small-scale studies explored how teachers’ beliefs and practices changed during very short to semester-long courses. Most researchers analyzed multiple types of data for triangulation and found both encouraging results documenting increasing expertise as well as offered thought-provoking insights into why teachers failed to collaborate and implement rules (child-centered activities, “English only”) promoted by their programs.

4.5.2 Studies on parents

The impact of very YLs’ parents on preschool FL learning is an emerging research topic contributing to deeper understanding of complexities of learning an additional language at preschool age. Comprehensive research on Polish EFL preschoolers (Rokita, Reference Rokita2007; Rokita-Jaśkow, Reference Rokita-Jaśkow2013, Reference Rokita-Jaśkow2015) showed that most parents were aware of the value of education, thought FL learning was easy for young children and believed that starting early would secure success in their children's FL learning. They attached an instrumental value to knowledge of English, while knowledge of a second FL (mostly French in the Polish context) was associated with cultural value. Parents living in villages had less realistic expectations of kindergarten L2 learning than parents living in cities. Higher SES parents wanted their children to learn a FL in order to one day become a part of an international community. They enrolled their children in private kindergartens, believed one FL was not enough, had higher expectations and aspirations for their children and more actively supported their children's FL learning. In contrast, lower SES parents considered their children's FL knowledge mainly as a means of getting a better job in the future, mostly enrolled them in public kindergartens and spent less time supporting their FL learning. Parental involvement generally included rote repetition of class material and watching foreign TV programs together. Parents who used the FL actively in their daily life supported their children's FL learning more actively. Although all parents entertained similar expectations for sons and daughters, they had higher aspirations for daughters and invested more in their daughters’ FL learning. Parents living in cities had slightly higher expectations than those from villages, who also entertained less realistic expectations of kindergarten FL learning. A comparison of parents’ attitudes who were themselves successful at FL learning with those who were not, indicated that parents in the former group were focused on instrumental goals (getting a good job or education), while the latter aimed at development of plurilingualism as well as cognitive and emotional development through learning a new language.

Jin et al. (Reference Jin, Zhou, Hu, Yang, Sun and Zhao2016) studied attitudes of Chinese parents towards their children learning EFL in kindergarten. Parents’ attitudes were overall very positive, but some differences were found between attitudes of parents in urban versus rural places, and between a metropolitan city versus smaller cities: attitudes were more positive in larger communities.

In a study conducted in the Netherlands, Keydeniers et al. (Reference Keydeniers, Aalberse, Andringa and Kuiken2021) analyzed language policy documents and questionnaire data collected from parents and teachers. They identified two underlying ideologies in the datasets: language policies aimed to involve Dutch children in English, German, or French programs to offer them an additional language. The pilot program, however, was conducted in English only and children came from overwhelmingly highly qualified multilingual international families representing the “educated elite” (p. 16).

As the above studies show, parents play a decisive role in pre-primary FL programs for their children. They tend to choose English, although in the most intensively examined Polish context, cultural values associated with other FLs also emerged. As far as the larger picture is concerned, parents’ status in society (urban vs. rural; level of education and L2 proficiency) interacts with how much money and effort they invest into their children's FL learning. These findings explain why children's SES is a good predictor of success at an early age, as was discussed in section 4.1.

4.6 Inside the preschool FL classroom

Research studies on how teaching processes and uses of languages impact children's engagement and L2 learning are highly valuable contributions to the field. As they zoom in on what happens in various activities in specific contexts, they offer insights into participants’ emic perspectives and the tiny steps in children's development. Findings show how children spontaneously draw on all their languages, including body language, in their repertoire.

4.6.1 Studies on classroom discourse and uses of languages in meaning making

Studies on storytelling and “picturebook” sharing in preschool English classrooms offer evidence on how such meaning-focused activities contribute to children's engagement and language awareness (e.g., Kearney & Barbour, Reference Kearney and Barbour2015) as well as how they increase context-embedded input and enrich interactions. The way Portuguese children responded to and benefited from repeated readings of picturebooks in English was analyzed by Mourão (Reference Mourão, Mourão and Lourenço2015b). Their responses in body language, Portuguese, and English were overwhelmingly analytical on the illustrations and the meaning of stories, documenting what they noticed and how they figured out meaning in context using their multiple resources.

Multiple projects explored how repetition contributes to FL learning. Roh and Lee (Reference Roh and Lee2018) examined its role in classroom discourse. They analyzed how a teacher's discourse strategies made children produce collective responses, notice and practice particular items in English, and how she adjusted her questions to the children's level of comprehension at two South Korean kindergartens. The study revealed how the teaching techniques scaffolded learning.

Physical movements and space associated with L2 learning were the focus of some insightful studies. Padial-Ruz et al. (Reference Padial-Ruz, García-Molina and Puga-González2019) documented how combining gestures and other physical activities to teach English vocabulary contributed to disadvantaged children's learning and motivation in Honduras. In a cooking-related task, Kiaer et al. (Reference Kiaer, Morgan-Brown and Choi2021) found that children manipulating real objects learnt more vocabulary than when they worked with pictures of the objects.

Four publications analyzed how English learning areas were utilized in various preprimary contexts. In a comparative study implemented in Portugal and South Korea, Robinson et al. (Reference Robinson, Mourão and Kang2015) and Mourão (Reference Mourão and Schwartz2018) observed children's spontaneous behavior in such designated areas and documented how they replicated teacher-led activities and used English chunks in their free play. A study conducted in Portugal (Mourão & Robinson, Reference Mourão, Robinson, Murphy and Evangelou2016) explored how a pre-primary and an English teacher collaborated on establishing English learning areas. Results of these enquiries were corroborated by Waddington et al. (Reference Waddington, Coto Bernal and Siqués Jofré2018) in their study carried out in the Spanish context. They also analyzed individual learners’ behavior in the learning area. They found that some children became more confident and participative than they were during regular classes, some preferred playing by themselves or just silently observing their classmates play, while others enjoyed playing in pairs or groups. In these studies, both L1 and L2 were used during play and peer correction was also observed. When choosing from the materials displayed in the learning area, the preschoolers often opted for those that could easily be used for games. All children reported highly positive attitudes to learning areas.

How the rule of “English only” guided teachers and impacted children was the focus of multiple studies. Song and Lee (Reference Song and Lee2018) compared how use of the target language only and code-switching in teacher talk contributed to meaning making and vocabulary learning in story telling activities in four kindergarten groups in South Korea. They concluded that some use of L1 was more conducive to scaffolding comprehension and it was also more popular with the children than the use of English only. In Poland, Scheffler and Domińska (Reference Scheffler and Domińska2018) interviewed teachers of English at private and state institutions about their, the children's and parents’ uses of Polish and English. In the more prestigious private school context, teachers tended to insist on English, whereas a more flexible approach was typical at the preschool where children's wellbeing seemed to be more of priority than using only English. Discipline and management emerged as issues, especially in the private school context where both teachers and parents tried to focus children's attention on activities in Polish. At a private kindergarten in Serbia, Prošić-Santovac and Radović (Reference Prošić-Santovac, Radović and Schwartz2018b) collected multiple data on teachers’ and children's uses of English and Serbian. They also found that although the school's policy included English only, children used Serbian overwhelmingly in their interactions.

Lessons learnt about what can cause trouble in a truly multilingual group of preschool children speaking a range of languages in Sweden were discussed by Björk-Willén (Reference Björk-Willén2008). This study documented how children rely on their knowledge of predictability in routines to figure out meaning in context, and how teachers can or fail to utilize such opportunities.

Finally, politeness was analyzed in two teachers’ audio-recorded English talk by Martí and Portolés (Reference Martí and Portolés2022) in two classes of Catalan and Spanish speakers. Although the teachers’ proficiency was different (B1 vs. C1), they both used simple directives and managed to bear in mind children's needs and not hurt their feelings or discourage them, to varying degrees.

These classroom-based studies examined multiple important points mentioned in theories (section 2) on how children learn languages. They focused on highly relevant but narrow aspects; therefore, the whole picture must be pieced together. They used observation, an appropriate but time-consuming data collection method, and emphasized the relevance of physical space, manipulation of real objects, movements, gestures, predictable routines, and spontaneous play in children's lives. They analyzed how teachers and children used L1, L2, and here and now references for meaning making, while using picturebooks, stories, games, or played spontaneously. However, longer transcribed data on interactions between adults and children, as well as among children using their languages are hardly included (but see Mourão, Reference Mourão and Schwartz2018 for short exchanges). It would be helpful to see examples of how repetition keeps children engaged but not bored. In our view, the most challenging aspect of working with children concerns tuning L2 input in age-appropriate tasks to their level, making sure they comprehend the input and document how they use the L2 over time. At the same time, children's short attention span or boring FL activities may lead to less engagement and misbehavior. Such issues emerged in only two studies, indicating that researchers focus on positive outcomes rather than difficulties.

4.6.2 ICT in preschool FL learning

The role information and communications technologies (ICT) can play in pre-primary FL learning is an emerging area. Alexiou and Vitoulis (Reference Alexiou, Vitoulis, Enever, Lindgren and Ivanov2014) conducted a small-scale experimental study to reveal how using an interactive website contributed to the learning of 15 words. They found encouraging results in favor of the experimental group. In another experimental study, an interactive e-book (Gohar, Reference Gohar2017) was used to improve kindergarteners’ print and phonological awareness, listening, and meaning making abilities in Egypt. Results supported uses of songs, interactive games, and audio files in the treatment group.

Very young Spanish children (nine to 33 months), the youngest ones in the database, participated in a replication of an experimental project (Ferjan Ramírez et al., Reference Ferjan Ramírez, Sheth and Kuhl2021) to measure how rapidly they developed in English, over 18 weeks, in one-hour weekly interactions with multiple native speakers in small groups. Teachers were trained in an online program called SparkLing™ to implement six principles: (1) they used a lot of input (2) in parentese (higher pitch, slower tempo, exaggerated intonation) (3) in playful interactions, (4) encouraging children to talk and interact by using prompts. Additionally, (5) input was offered by multiple native speakers, and (6) they scaffolded playful activities. All children wore a vest with a digital recorder to tape their vocalizations in English, and took a computerized test conducted on a touch screen to assess their word comprehension both in Spanish and English before and after the intervention. The authors found “rapid gains from social language exposure” (p. 13) in children's vocalizations in English irrespective of their socioeconomic background, with older children learning faster. They claimed that the amount of input in playful activities was conducive to both receptive and productive vocabulary learning, although how they came to this conclusion is not clear.

These few studies do not reflect the potential ICT may offer. Most probably, many young children use technology for entertainment; examples of how they benefit from exposure to age-appropriate authentic programs (e.g., cartoons, games, visuals) in pre-primary FL classes is missing. ICT could be used more widely for collecting data, a point examined in only one paper.

5. Approaches to research into preschool FL programs

Multiple authors have addressed how young children can and should be studied. This section is devoted to presenting the key ideas from two focal points: how stakeholders have been researched and how children have been assessed.

5.1 How preschool children, their teachers, and parents are researched: Approaches to research design

Several authors discussed how very young learners of FLs, their parents, and teachers were studied. Mourão (Reference Mourão, Garton and Copland2019) stressed that preschool FL learning and teaching is a largely under-researched area to the extent that systematic research of all its aspects is needed. She calls for compiling robust enough data so that FL learning policies can be based on valid and reliable research evidence. This kind of evidence, in our view, is missing at this point for three reasons: (1) lack of model and clear curricular aims, (2) research design issues, and (3) the research questions researchers aim to answer. These points are interrelated, but we discuss them one by one.

There is no widely accepted model of pre-primary FL learning integrating how children's IDs and their L1 and L2 development interact with aspects such as their teachers’ competences in L1 and L2, togerther with age-appropriate classroom methodology, classroom-related variables, and extra-curricular learning opportunities (Nikolov & Lugossy, Reference Nikolov, Lugossy and Schwartz2022, pp. 27–28). FL programs which fail to specifiy aims (discussed in 5.2) pose an additional challenge. A model would allow researchers to test how variables work in specific contexts by using a quantitative approach: (quasi)-experimental or correlational or survey studies (Creswell, Reference Creswell2012, p. 12). Such a model could be proposed based on exploratory studies working towards a unified theory.

The 74 publications included 24 quantitative, 28 qualitative, and 22 mixed methods inquiries, showing that all three approaches to research design are present. The studies using a quantitative approach tested relationships between variables on constructs assumed to be known. A complex example is Unsworth et al. (Reference Unsworth, Persson, Prins and de Bot2014): this longitudinal experimental study involving 168 Dutch children learning English in 17 groups measured the children's aptitude and L2 progress, their teachers’ English proficiency, and the amount of input received. They found that children already had measurable receptive vocabulary at initial data-gathering (measured with a validated test for L1 English learners), the control group also improved, and increase in vocabulary in all groups was minimal. No information was available on what happened in the 17 classes during the two years. Thus, applying a reasonable model and instruments validated for older FL learners or native speakers offers less valid and reliable results with very young children without analyzing classroom data through a small lens.

As for the research design used with different stakeholders, teachers and parents were either surveyed or researchers elicited qualitative data on teachers’ views, beliefs, and practices using a range of open-ended techniques: e.g., reflections, focus groups, interviews, and video-taped observations. Such data are often collected from adults with validated instruments, and they tend to allow researchers to return with valid and reliable, or credible and trustworthy findings. The most challenging issue is how the interaction between teachers and children is studied in age-appropriate ways, for example, in teacher-led activities and in free play as children interact (Mourão, Reference Mourão and Schwartz2018; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Mourão and Kang2015). As pre-primary FL learning is still unchartered territory in terms of research, exploratory qualitative inquiries are conducted. These are valuable and necessary for building models to allow researchers to work towards the larger picture of what variables contribute to success in pre-primary FL programs. How success is defined, however, is a recurring issue. We argue that curricular aims should include attitudinal, emotional, cognitive, social, and L2 targets (Johnstone, Reference Johnstone, Garton and Copland2019) in line with what children in this age group are expected to be able to do in their L1(s) (see 5.2). This latter aspect is typically only implied rather than explicitly stated in research.

The research questions posed have important implications for how narrowly focused studies are, what they add to current knowledge, how many participants are involved, how datasets can be triangulated, and whether the findings can or cannot be generalized to other populations or replicated. As Nikolov and Lugossy (Reference Nikolov, Lugossy and Schwartz2022) pointed out, research on preschool FL programs tend to focus on either one or a few variables (e.g., vocabulary, explicit learning, repetition, motivation, learning area, teachers’ competences in L2 and teaching methodology). Few studies are longitudinal over years, and they fail to add to the formulation of realistic aims, optimal teaching conditions, patterns in implicit learning, or address how children with learning difficulties cope with challenges in FL learning. An additional problem, as Alstad and Mourão (Reference Alstad and Mourão2021) pointed out, is a lack of interdisciplinary research.

Although varied research methods were used in the studies in our database, as Nikolov and Lugossy (Reference Nikolov, Lugossy and Schwartz2022) observed, most are small-scale and some of the instruments applied are poorly designed. For example, Yeung et al. (Reference Yeung, Siegel and Chan2013) administered an explicit language-enriched phonological awareness program over 12 weeks, measured the outcomes on 12 tests unrelated to the treatment, and found that the results were not valid. Coyle and Gómez Gracia (Reference Coyle and Gómez Gracia2014) taught five nouns in 3 × 30 minutes in a song; as for how many words children could recall, the mean score was 1 after treatment. Jin et al. (Reference Jin, Zhou, Hu, Yang, Sun and Zhao2016) elicited metaphors from Chinese children on what learning English was like. They did not realize that metaphors were beyond the children's cognitive abilities and the visuals they used misled them. Furthermore, many studies involved privileged preschool learners of English of educated elite families (e.g., Keydeniers et al., Reference Keydeniers, Aalberse, Andringa and Kuiken2021), whose parents could afford to pay for tuition in private programs. No study involved children with learning difficulties or behavioral problems or low SES.

Teachers’ roles are of paramount importance, but studies have mostly focused on formal aspects of their education, general attitudes to very early FL learning, and collaboration with homeroom and other FL teachers and parents. There has been hardly any in-depth research on teacher strategies, cognition and beliefs, their attitudes to and motivation for very early FL teaching, self-perception of efficacy, and professional and personal development with increasing teaching experience. Teacher studies have mostly relied on questionnaires, interviews, observations, and teacher logs. Qualitative research and longitudinal studies could offer a deeper understanding of FL teachers’ roles in preschool FL learning (Nikolov & Lugossy, Reference Nikolov, Lugossy and Schwartz2022; Thieme et al., Reference Thieme, Hanekamp, Andringa, Verhagen and Kuiken2021).

Studies on parents focused on their beliefs about FL learning, expectations, and aspirations concerning their child's L2 development, involvement in the child's learning at home, and the impact of family SES on these factors. Some attention has also been paid to parental pressure on preschool institutions to introduce FL learning and to insist on an English-only approach. Questionnaires and interviews have been the main instruments used in these studies. For a deeper understanding of parents’ roles, we need more in-depth longitudinal research on parental influence on child FL learners’ attitudes, involvement in their L2 learning, collaboration with teachers as well as other parents, on their awareness about FL teaching and learning processes, and ways they can help their child with emerging FL learning problems (e.g., anxiety, feeling of failure) (Nikolov & Lugossy, Reference Nikolov, Lugossy and Schwartz2022).

5.2 Assessment of preschool FL learners: Is it all about learning words?

None of the language policy documents and curricula specified how pre-primary children's attitudes and openness to languages are expected to develop, what very young learners are expected to be able to do in their new language at different stages in pre-primary FL programs, how those are aligned with their cognitive and L1 development, and how teachers should diagnose to what extent children have achieved those targets. Therefore, it is unclear what the constructs are and how they can be operationalized (Nikolov & Timpe-Laughlin, Reference Nikolov and Timpe-Laughlin2021). However, many projects assessed how children progressed in their FL learning and what they could do in a FL over a relatively short time (typically weeks). These are problematic points in the studies on pre-primary FL learners for multiple reasons. As their development is very slow (see section 2), realistically, only minimal development is to be expected, and this is what studies on vocabulary have found. At what points and to what extent it is possible and ethical to measure this slow development are worth considering. What happens with the results, who uses them and for what purposes, apart from publishing them, are also in need of discussion. We found hardly any data on how assessment may impact the children themselves (for a positive example, see Prošić-Santovac & Navratil, Reference Prošić-Santovac, Navratil, Prošić-Santovac and Rixon2019, for a negative example where testing caused sickness see Jin et al., Reference Jin, Zhou, Hu, Yang, Sun and Zhao2016). Concerns remain over what can realistically be concluded or generalized from such assessments using validated tests for L1 learners and researcher-designed tests. Nikolov and Timpe-Laughlin (Reference Nikolov and Timpe-Laughlin2021) argued for redefining the aims of early FL assessment and replacing language tests with longitudinal observation that goes beyond linguistic results and includes the child's general cognitive, social, intercultural, and other development, together with their awareness of languages and other important values in life.

In our dataset, researchers collected assessment data on pre-primary FL learners’ progress and achievement along the lines they defined. Out of the 74 empirical studies, 32 used one or more tests, including 28 publications reporting L2 vocabulary test results. The number of items in receptive vocabulary tests, the most widely used test type, ranged between 5 and 35. Two studies included tests of L1 (Polish and Chinese); all other projects assessed children only in their L2 and some in other domains also (e.g., aptitude). This sharp focus on vocabulary (Alexiou et al., Reference Alexiou, Roghani, Milton, Prošić-Santovac and Rixon2019) would be in line with theories on how children learn languages (section 2) if all researchers took into consideration what task types were familiar enough to make sure that the tests were valid and reliable (Butler, Reference Butler2019) and they measured what this age group is good at (i.e, implicit rather than explicit learning). For example, Davis and Fan (Reference Davis and Fan2016) taught 64 Chinese children 15 short sentences in songs or in choral repetition in 15 lessons of 40 minutes over seven weeks and tested their productive vocabulary by asking them to say what they could see in 15 visual prompts. They reported results in mean length of utterance, as they expected multiword answers. Results were similar in both conditions: most children said either nothing or a single word. Neither the teaching approach nor the assessment were appropriate, although implicit chunk learning would have been a legitimate focus, missing from the dataset. In another quasi-experimental study, Albaladejo Albaladejo et al. (Reference Albaladejo Albaladejo, Coyle and de Larios2018) tested how 17 Spanish learners of English learnt five nouns in three types of activities: by listening to stories or songs or both. Test results showed that the story was most conducive to learning; however, three of the five words in the story were cognates and none in the other conditions.

An additional point concerns the content and cognitive validity of vocabulary tests used with very young learners. As was mentioned earlier, Unsworth et al. (Reference Unsworth, Persson, Prins and de Bot2014 and other studies) used a vocabulary test validated for English native speakers to compare how much progress Dutch children made over two years. Winke et al. (Reference Winke, Jieun, Ahn, Choi, Cui and Yoon2018) analyzed the cognitive validity of English tests for young learners by comparing results of L1 and L2 English test takers; they raised the question not only of how children using the L2 as their L1 would perform on these tests, but also how the children taking the L2 tests would manage to do such tests in their own L1, and if they ever do so.

The recurring theme of comparing implicit vs. explicit learning, and not conceptualizing them along a continuum, prevents researchers from understanding how children develop in these programs. No study looked at both dimensions of receptive and productive vocabulary and formulaic language or chunks as continua. The very short time devoted to (quasi)experimental projects indicates that researchers tend to bear in mind either children with high aptitude who can learn fast and their results can be measured in short treatment studies, or they think in terms of what assumptions are reasonable with older learners.

Furthermore, as discussed in section 4, empirical studies on children's IDs, language awareness, and learning of various aspects of communicative competence, used certain tests to tap into either explicit or implicit learning or both, although they were not all framed as assessment. The issues related to these publications concern why and how children are assessed, how familiar they are with the tasks used for testing, how valid and reliable the tests are, how they are aligned with curricula and how children learn new languages, and in what ways tests are conducive to learning (Nikolov & Timpe-Laughlin, Reference Nikolov and Timpe-Laughlin2021) and contribute to children's wellbeing in more general terms.