1 Introduction

In this paper, we are interested in how many integers

![]() $\leq N$

are covered by the values taken by the quadratic forms

$\leq N$

are covered by the values taken by the quadratic forms

![]() $x^2 + dy^2$

,

$x^2 + dy^2$

,

![]() $d \leq \Delta $

. Our main result is the following, which gives a fairly complete answer to this question.

$d \leq \Delta $

. Our main result is the following, which gives a fairly complete answer to this question.

Theorem 1.1 (Main theorem)

Let N be large and write, for some real number

![]() $\alpha $

,

$\alpha $

,

Then

where

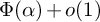

![]() $\Phi $

is the Gaussian distribution function

$\Phi $

is the Gaussian distribution function

![]() $\Phi (\alpha ) = \frac {1}{\sqrt {2\pi }} \int ^{\alpha }_{-\infty } e^{-x^2/2} dx$

.

$\Phi (\alpha ) = \frac {1}{\sqrt {2\pi }} \int ^{\alpha }_{-\infty } e^{-x^2/2} dx$

.

The problem of covering integers by this family of binary quadratic forms seems to have been first considered in the work of Hanson and Vaughan [Reference Hanson and Vaughan12]. Using the circle method, they established that almost all integers

![]() $n\leq N$

may be covered with

$n\leq N$

may be covered with

![]() $\Delta = \log N (\log \log N)^{3+\varepsilon }$

for any

$\Delta = \log N (\log \log N)^{3+\varepsilon }$

for any

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

and that a positive proportion of the integers below N may be covered using

$\varepsilon>0$

and that a positive proportion of the integers below N may be covered using

![]() $\Delta = \log N \log \log N$

. Diao [Reference Diao7] found a much shorter proof of the latter result, and in his argument d could be restricted to prime values so that a smaller set of forms is used.

$\Delta = \log N \log \log N$

. Diao [Reference Diao7] found a much shorter proof of the latter result, and in his argument d could be restricted to prime values so that a smaller set of forms is used.

Landau established that the number of integers below N that are sums of two squares is

![]() $\sim BN/(\log N)^{1/2}$

for a positive constant B. This was extended by Bernays to show that for any fixed primitive positive definite binary quadratic form f, the number of integers below N that are represented by f is

$\sim BN/(\log N)^{1/2}$

for a positive constant B. This was extended by Bernays to show that for any fixed primitive positive definite binary quadratic form f, the number of integers below N that are represented by f is

![]() $\sim B_f N (\log N)^{-1/2}$

, for a positive constant

$\sim B_f N (\log N)^{-1/2}$

, for a positive constant

![]() $B_f$

(which in fact depends only on the discriminant of f). More recently, Blomer [Reference Blomer1, Reference Blomer2] and Blomer and Granville [Reference Blomer and Granville3] consider in detail the number of integers up to N that are represented by f uniformly in the form f (thus allowing the discriminant to grow with N). These results, taken with the union bound, suggest that if

$B_f$

(which in fact depends only on the discriminant of f). More recently, Blomer [Reference Blomer1, Reference Blomer2] and Blomer and Granville [Reference Blomer and Granville3] consider in detail the number of integers up to N that are represented by f uniformly in the form f (thus allowing the discriminant to grow with N). These results, taken with the union bound, suggest that if

![]() $\Delta $

is smaller than

$\Delta $

is smaller than

![]() $(\log N)^{1/2-\varepsilon }$

, then almost all

$(\log N)^{1/2-\varepsilon }$

, then almost all

![]() $n\leq N$

cannot be covered by the forms

$n\leq N$

cannot be covered by the forms

![]() $x^2+dy^2$

with

$x^2+dy^2$

with

![]() $d\leq \Delta $

. However, as Theorem 1.1 reveals, the true threshold for

$d\leq \Delta $

. However, as Theorem 1.1 reveals, the true threshold for

![]() $\Delta $

is neither

$\Delta $

is neither

![]() $(\log N)^{1/2}$

nor

$(\log N)^{1/2}$

nor

![]() $\log N$

but instead

$\log N$

but instead

![]() $(\log N)^{\log 2}$

.

$(\log N)^{\log 2}$

.

We shall in fact prove a more precise version of Theorem 1.1, counting the number of integers below N with k prime factors that may be represented as

![]() $x^2+ dy^2$

with

$x^2+ dy^2$

with

![]() $d\leq \Delta $

. Throughout, let

$d\leq \Delta $

. Throughout, let

![]() $\Omega (n)$

denote the number of prime factors of n counted with multiplicity, and define

$\Omega (n)$

denote the number of prime factors of n counted with multiplicity, and define

Recall that most integers below N have about

![]() $\log \log N$

prime factors, a result first established by Hardy and Ramanujan. The well-known work of Erdős and Kac established that

$\log \log N$

prime factors, a result first established by Hardy and Ramanujan. The well-known work of Erdős and Kac established that

![]() $\Omega (n)$

has a normal distribution with mean

$\Omega (n)$

has a normal distribution with mean

![]() $\sim \log \log N$

and variance

$\sim \log \log N$

and variance

![]() $\sim \log \log N$

, while Selberg’s work [Reference Selberg16] gave still more precise results establishing an asymptotic formula for

$\sim \log \log N$

, while Selberg’s work [Reference Selberg16] gave still more precise results establishing an asymptotic formula for

![]() ${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

uniformly in a wide range of k. To reduce the visual complexity of expressions involving double logs later on, it is convenient to set (throughout the paper)

${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

uniformly in a wide range of k. To reduce the visual complexity of expressions involving double logs later on, it is convenient to set (throughout the paper)

The following simplified version of Selberg’s result is an immediate consequence of [Reference Tenenbaum17, Theorem II.6.5].

Lemma 1.2. Let N be large. Uniformly for integers k in the range

![]() $|k -k_0| \leq \tfrac 12 k_0$

, we have

$|k -k_0| \leq \tfrac 12 k_0$

, we have

$$\begin{align*}|{\mathcal A}(N,k)| = \frac{N}{\log N} \frac{k_0^k}{k!}\Big( 1+ O\Big( \frac{1+|k-k_0|}{k_0}\Big)\Big). \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}|{\mathcal A}(N,k)| = \frac{N}{\log N} \frac{k_0^k}{k!}\Big( 1+ O\Big( \frac{1+|k-k_0|}{k_0}\Big)\Big). \end{align*}$$

For a given k in a suitable interval around

![]() $\log \log N$

, we shall show (the ‘upper bound’, Theorem 1.3 below) that almost none of the integers in

$\log \log N$

, we shall show (the ‘upper bound’, Theorem 1.3 below) that almost none of the integers in

![]() ${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

are represented by

${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

are represented by

![]() $x^2+dy^2$

with

$x^2+dy^2$

with

![]() $d\leq \Delta $

if

$d\leq \Delta $

if

![]() $\Delta $

is a bit smaller than

$\Delta $

is a bit smaller than

![]() $2^k$

. This changes when

$2^k$

. This changes when

![]() $\Delta $

becomes a bit larger than

$\Delta $

becomes a bit larger than

![]() $2^k$

, when almost all the integers in

$2^k$

, when almost all the integers in

![]() ${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

may be so represented. This is the ‘lower bound’, Theorem 1.4 below. From these results, Theorem 1.1 will follow swiftly.

${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

may be so represented. This is the ‘lower bound’, Theorem 1.4 below. From these results, Theorem 1.1 will follow swiftly.

We turn now to the precise statements.

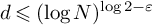

Theorem 1.3 (Upper bound)

Let N be large, and let k be an integer in the range

Suppose

![]() $\Delta \leq 2^k/k^4$

. The number of integers

$\Delta \leq 2^k/k^4$

. The number of integers

![]() $n \in {\mathcal A}(N,k)$

that may be written as

$n \in {\mathcal A}(N,k)$

that may be written as

![]() $x^2 + dy^2$

with

$x^2 + dy^2$

with

![]() $1\leq d\leq \Delta $

is

$1\leq d\leq \Delta $

is

![]() $\ll N/k_0$

.

$\ll N/k_0$

.

An application of Stirling’s formula (see (2.3) below) shows that for k in the range (1.1)

$$ \begin{align*}|{\mathcal A}(N,k)| = \frac{N}{\sqrt{2\pi k_0}} \exp\Big( -\frac{(k-k_0)^2}{2k_0}\Big) \Big( 1+ O\Big( k_0^{-1/5}\Big) \Big). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}|{\mathcal A}(N,k)| = \frac{N}{\sqrt{2\pi k_0}} \exp\Big( -\frac{(k-k_0)^2}{2k_0}\Big) \Big( 1+ O\Big( k_0^{-1/5}\Big) \Big). \end{align*} $$

Thus, Theorem 1.3 is really of interest only when

![]() $|k-k_0| \leq (k_0 \log k_0)^{1/2}$

. This range still includes most typical integers below N, and Theorem 1.3 may be used to establish the upper bound for the integers below N of the form

$|k-k_0| \leq (k_0 \log k_0)^{1/2}$

. This range still includes most typical integers below N, and Theorem 1.3 may be used to establish the upper bound for the integers below N of the form

![]() $x^2+dy^2$

with

$x^2+dy^2$

with

![]() $d\leq \Delta $

that is implicit in Theorem 1.1. The corresponding lower bound in Theorem 1.1 is implied by the following result.

$d\leq \Delta $

that is implicit in Theorem 1.1. The corresponding lower bound in Theorem 1.1 is implied by the following result.

Theorem 1.4 (Lower bound)

Let N be large, and let k be an integer in the range given in (1.1). Suppose

![]() $\Delta \geq k^3 2^k$

. Let

$\Delta \geq k^3 2^k$

. Let

![]() ${\mathcal E}(N,k)$

denote the set of integers in

${\mathcal E}(N,k)$

denote the set of integers in

![]() ${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

that cannot be represented as

${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

that cannot be represented as

![]() $x^2+dy^2$

with

$x^2+dy^2$

with

![]() $d\leq \Delta $

. Then

$d\leq \Delta $

. Then

Similarly to Theorem 1.3, Theorem 1.4 is really of interest only in the range

but this range includes most typical integers below N. In Section 2, we shall deduce our main result Theorem 1.1 from Theorems 1.3 and 1.4.

Since our main interest is in establishing Theorem 1.1, we have made no effort to optimize the error terms and ranges for k in Theorems 1.3 and 1.4. It would be of interest to establish analogues of these results uniformly in a wide range of k (although when k is large it may be better to work with

![]() $\omega (n)=k$

, where

$\omega (n)=k$

, where

![]() $\omega (n)$

counts the number of distinct prime factors of n). One case of particular interest may be

$\omega (n)$

counts the number of distinct prime factors of n). One case of particular interest may be

![]() $k=1$

: representing primes up to N using the quadratic forms

$k=1$

: representing primes up to N using the quadratic forms

![]() $x^2 +dy^2$

with

$x^2 +dy^2$

with

![]() $d\leq \Delta $

. Here, it would be possible to establish that a proportion

$d\leq \Delta $

. Here, it would be possible to establish that a proportion

![]() $\rho (\Delta )$

of the primes up to N may be so represented with

$\rho (\Delta )$

of the primes up to N may be so represented with

![]() $\rho (1)=1/2$

(by Fermat’s result on representing primes of the form

$\rho (1)=1/2$

(by Fermat’s result on representing primes of the form

![]() $1 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

as a sum of two squares),

$1 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

as a sum of two squares),

![]() $\rho (\Delta ) <1$

for all

$\rho (\Delta ) <1$

for all

![]() $\Delta $

, and

$\Delta $

, and

![]() $\rho (\Delta ) \to 1$

as

$\rho (\Delta ) \to 1$

as

![]() $\Delta \to \infty $

. Determining

$\Delta \to \infty $

. Determining

![]() $\rho (\Delta )$

precisely, or understanding its precise asymptotic behavior as

$\rho (\Delta )$

precisely, or understanding its precise asymptotic behavior as

![]() $\Delta $

gets large, seems like a challenging and delicate problem.

$\Delta $

gets large, seems like a challenging and delicate problem.

Let us indicate very briefly the ideas behind Theorems 1.3 and 1.4; here and in the rest of the introduction, we shall be a little informal and also assume that the reader is familiar with the classical theory of binary quadratic forms (which will be recalled in Section 3). Recall that a square-free integer n may be represented by some binary quadratic form of negative discriminant D if and only if

![]() $\chi _D(p)= 1$

for all primes p dividing n (assume that n is coprime to D). If n has k prime factors, then each condition

$\chi _D(p)= 1$

for all primes p dividing n (assume that n is coprime to D). If n has k prime factors, then each condition

![]() $\chi _D(p)=1$

has a

$\chi _D(p)=1$

has a

![]() $50\%$

chance of occurring so that n may be represented by some binary quadratic form of discriminant D with probability

$50\%$

chance of occurring so that n may be represented by some binary quadratic form of discriminant D with probability

![]() $2^{-k}$

. This suggests that

$2^{-k}$

. This suggests that

![]() $\Delta $

must be about size

$\Delta $

must be about size

![]() $2^k$

in order to have a chance of representing many integers with k prime factors. This is the idea behind Theorem 1.3, and it can be made precise without too much difficulty (see Section 4).

$2^k$

in order to have a chance of representing many integers with k prime factors. This is the idea behind Theorem 1.3, and it can be made precise without too much difficulty (see Section 4).

The more difficult part of our argument is Theorem 1.4, which constitutes the bulk of the paper. If

![]() $\Delta $

is substantially larger than

$\Delta $

is substantially larger than

![]() $2^k$

, then the heuristic that we just mentioned would suggest that for most integers

$2^k$

, then the heuristic that we just mentioned would suggest that for most integers

![]() $n\leq N$

with k prime factors there would be some negative discriminant D with

$n\leq N$

with k prime factors there would be some negative discriminant D with

![]() $|D|\leq \Delta $

such that n is representable by some binary quadratic form of discriminant D, and indeed, there would be a total of about

$|D|\leq \Delta $

such that n is representable by some binary quadratic form of discriminant D, and indeed, there would be a total of about

![]() $2^k$

such representations of n. The number of inequivalent classes of binary quadratic forms of discriminant D is the class number, which is of size

$2^k$

such representations of n. The number of inequivalent classes of binary quadratic forms of discriminant D is the class number, which is of size

![]() $|D|^{1/2+ o(1)}$

. It is therefore likely that some of the

$|D|^{1/2+ o(1)}$

. It is therefore likely that some of the

![]() $2^k$

(which is about

$2^k$

(which is about

![]() $\Delta $

) representations of n would come from the principal form

$\Delta $

) representations of n would come from the principal form

![]() $x^2+dy^2$

(corresponding to the discriminant

$x^2+dy^2$

(corresponding to the discriminant

![]() $D=-4d$

) and indeed that there should be about

$D=-4d$

) and indeed that there should be about

![]() $2^k/|D|^{1/2+o(1)}$

representations of n by

$2^k/|D|^{1/2+o(1)}$

representations of n by

![]() $x^2+dy^2$

. We make this heuristic precise by using class group characters and their associated L-functions, together with a second moment method. It would be relatively straightforward to obtain a version of Theorem 1.4 where a positive proportion of the elements in

$x^2+dy^2$

. We make this heuristic precise by using class group characters and their associated L-functions, together with a second moment method. It would be relatively straightforward to obtain a version of Theorem 1.4 where a positive proportion of the elements in

![]() ${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

are represented by the forms

${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

are represented by the forms

![]() $x^2+dy^2$

with

$x^2+dy^2$

with

![]() $d\leq \Delta $

. However, it is more delicate to obtain almost all integers in

$d\leq \Delta $

. However, it is more delicate to obtain almost all integers in

![]() ${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

, and to achieve this we impose congruence conditions on d for all primes p below a slowly growing parameter W. A key fact is that when discriminants d are restricted to such progressions, the value of

${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

, and to achieve this we impose congruence conditions on d for all primes p below a slowly growing parameter W. A key fact is that when discriminants d are restricted to such progressions, the value of

![]() $L(1,\chi _d)$

remains more or less constant. To simplify genus theory considerations, we further restrict attention to prime values of d, but this is merely a matter of convenience.

$L(1,\chi _d)$

remains more or less constant. To simplify genus theory considerations, we further restrict attention to prime values of d, but this is merely a matter of convenience.

For k sufficiently close to

![]() $k_0$

, Theorems 1.3 and 1.4 show that the number of represented elements in

$k_0$

, Theorems 1.3 and 1.4 show that the number of represented elements in

![]() ${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

undergoes a rapid phase transition as one goes from

${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

undergoes a rapid phase transition as one goes from

![]() $\Delta = 2^k/k^4$

(when

$\Delta = 2^k/k^4$

(when

![]() $0\%$

of

$0\%$

of

![]() ${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

is covered) to

${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

is covered) to

![]() $\Delta = 2^k k^3$

(when

$\Delta = 2^k k^3$

(when

![]() $100\%$

of

$100\%$

of

![]() ${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

is covered). While there is some scope to narrow the gap between

${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

is covered). While there is some scope to narrow the gap between

![]() $2^k/k^4$

and

$2^k/k^4$

and

![]() $2^k k^3$

, the restriction to prime values of d in our proof of Theorem 1.4 would prevent us from fully closing this gap. It seems likely that a more precise cutoff phenomenon occurs: When

$2^k k^3$

, the restriction to prime values of d in our proof of Theorem 1.4 would prevent us from fully closing this gap. It seems likely that a more precise cutoff phenomenon occurs: When

![]() $\Delta = \beta \sqrt {k} 2^k$

, there is a proportion

$\Delta = \beta \sqrt {k} 2^k$

, there is a proportion

![]() $p(\beta )$

of integers in

$p(\beta )$

of integers in

![]() ${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

that are represented, with

${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

that are represented, with

![]() $0< p(\beta ) <1$

for all

$0< p(\beta ) <1$

for all

![]() $0 < \beta < \infty $

, and with

$0 < \beta < \infty $

, and with

![]() $p(\beta ) \to 0$

as

$p(\beta ) \to 0$

as

![]() $\beta \to 0$

and

$\beta \to 0$

and

![]() $p(\beta ) \to 1$

as

$p(\beta ) \to 1$

as

![]() $\beta \to \infty $

. Possibly our arguments, together with additional ideas taking into account genus theory, could be used to establish part of this cutoff phenomenon, and we hope that an interested reader will take up the challenge.

$\beta \to \infty $

. Possibly our arguments, together with additional ideas taking into account genus theory, could be used to establish part of this cutoff phenomenon, and we hope that an interested reader will take up the challenge.

Our discussion so far has been confined to representing almost all integers below N using the forms

![]() $x^2+dy^2$

with

$x^2+dy^2$

with

![]() $d\leq \Delta $

. It is natural to ask what happens if all integers below N are to be represented. Taking

$d\leq \Delta $

. It is natural to ask what happens if all integers below N are to be represented. Taking

![]() $x= \lfloor \sqrt {n}\rfloor $

and

$x= \lfloor \sqrt {n}\rfloor $

and

![]() $y=1$

, we see that

$y=1$

, we see that

![]() $\Delta = 2\sqrt {N}$

suffices, and going beyond this trivial bound already seems an interesting problem. Since integers below N have

$\Delta = 2\sqrt {N}$

suffices, and going beyond this trivial bound already seems an interesting problem. Since integers below N have

![]() $\ll \log N/\log \log N$

distinct prime factors, extrapolating Theorem 1.4 we may expect that

$\ll \log N/\log \log N$

distinct prime factors, extrapolating Theorem 1.4 we may expect that

![]() $\Delta =\exp ( C \log N/\log \log N)$

is sufficient for some constant

$\Delta =\exp ( C \log N/\log \log N)$

is sufficient for some constant

![]() $C>0$

. As evidence towards this conjecture, we note that progress can be made in two weaker versions.

$C>0$

. As evidence towards this conjecture, we note that progress can be made in two weaker versions.

By a simple application of the pigeonhole principle, one can show that every positive integer below N may be represented by some nondegenerate binary quadratic form f with

![]() $|\text {disc}(f)| \leq \exp (C \log N/\log \log N)$

with C being any constant larger than

$|\text {disc}(f)| \leq \exp (C \log N/\log \log N)$

with C being any constant larger than

![]() $\log 4$

. Here, nondegenerate means that the quadratic form does not factor into linear forms or, equivalently, that the discriminant is not a square. In fact, all elements of

$\log 4$

. Here, nondegenerate means that the quadratic form does not factor into linear forms or, equivalently, that the discriminant is not a square. In fact, all elements of

![]() ${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

can be represented by some nondegenerate binary quadratic form with absolute discriminant

${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

can be represented by some nondegenerate binary quadratic form with absolute discriminant

![]() $\ll 4^k$

(for instance, all primes are of the form

$\ll 4^k$

(for instance, all primes are of the form

![]() $x^2+y^2$

,

$x^2+y^2$

,

![]() $x^2+ 2y^2$

or

$x^2+ 2y^2$

or

![]() $x^2-2y^2$

). The pigeonhole argument does not allow us to restrict attention to positive definite forms (although one can restrict attention to indefinite forms), let alone the smaller family of principal positive definite forms. Assuming GRH for quadratic Dirichlet L-functions it can be shown that all integers below N may be represented by some positive definite binary quadratic form with absolute discriminant below

$x^2-2y^2$

). The pigeonhole argument does not allow us to restrict attention to positive definite forms (although one can restrict attention to indefinite forms), let alone the smaller family of principal positive definite forms. Assuming GRH for quadratic Dirichlet L-functions it can be shown that all integers below N may be represented by some positive definite binary quadratic form with absolute discriminant below

![]() $\exp (C \log N/\log \log N)$

for any

$\exp (C \log N/\log \log N)$

for any

![]() $C> \log 4$

and indeed that all elements in

$C> \log 4$

and indeed that all elements in

![]() ${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

can be represented by such forms with absolute discriminant

${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

can be represented by such forms with absolute discriminant

![]() $\ll 4^k (\log N)^4$

.

$\ll 4^k (\log N)^4$

.

In the other direction, we may ask how large must

![]() $\Delta $

necessarily be if all integers

$\Delta $

necessarily be if all integers

![]() $n\leq N$

are represented as

$n\leq N$

are represented as

![]() $x^2 +dy^2$

with

$x^2 +dy^2$

with

![]() $d\leq \Delta $

. Complementing our discussion above, we can establish here that

$d\leq \Delta $

. Complementing our discussion above, we can establish here that

![]() $\Delta $

must be at least

$\Delta $

must be at least

![]() $\Delta _0= \exp (c \log N/\log \log N)$

for a positive constant c. In fact, we can establish the stronger result that there exists a square-free integer

$\Delta _0= \exp (c \log N/\log \log N)$

for a positive constant c. In fact, we can establish the stronger result that there exists a square-free integer

![]() $n\leq N$

such that for any fundamental discriminant d with

$n\leq N$

such that for any fundamental discriminant d with

![]() $1 < |d|\leq \Delta _0$

there exists a prime factor p of n with

$1 < |d|\leq \Delta _0$

there exists a prime factor p of n with

![]() $\chi _d(p)=-1$

. Such an integer n cannot be represented by any primitive nondegenerate binary quadratic form with absolute discriminant below

$\chi _d(p)=-1$

. Such an integer n cannot be represented by any primitive nondegenerate binary quadratic form with absolute discriminant below

![]() $\Delta _0$

. This result, which may be viewed as a variant of the least quadratic nonresidue problem, follows from an application of log-free zero density estimates; details will be supplied elsewhere.

$\Delta _0$

. This result, which may be viewed as a variant of the least quadratic nonresidue problem, follows from an application of log-free zero density estimates; details will be supplied elsewhere.

Lastly, we draw attention to three papers from the literature where related problems concerning the integers represented by a family of binary quadratic forms are considered: Blomer’s work on sums of two squareful numbers [Reference Blomer1], the work of Bourgain and Fuchs [Reference Bourgain and Fuchs4] on Apollonian circle packings and the work of Ghosh and Sarnak [Reference Ghosh and Sarnak10] on Markoff-type cubic surfaces.

Notation. For the most part notation will be introduced when it is needed. However, we remind the reader that

![]() $k_0$

will always denote

$k_0$

will always denote

![]() $\log \log N$

. From Section 5 onwards, W will denote a quantity which tends to infinity with N sufficiently slowly; we will take

$\log \log N$

. From Section 5 onwards, W will denote a quantity which tends to infinity with N sufficiently slowly; we will take

![]() $W := \log \log \log N$

for definiteness.

$W := \log \log \log N$

for definiteness.

Plan of the paper. Section 2 is devoted to the proof that the upper and lower bounds (Theorems 1.3 and 1.4, respectively) imply the main theorem, Theorem 1.1. Section 3 gives some standard background on binary quadratic forms which will be used throughout the rest of the paper. In Section 4, we prove the relatively straightforward upper bound, Theorem 1.3.

The remainder of the paper is devoted to the much more involved proof of the lower bound, Theorem 1.4. First, we formulate a more technical variant of this result, Theorem 5.1. This result allows us to restrict attention to representing integers not divisible by

![]() $4$

, using only quadratic forms

$4$

, using only quadratic forms

![]() $x^2 + dy^2$

with d ranging over primes in certain congruence classes. The deduction of Theorem 1.4 from Theorem 5.1 is short and is given immediately after the statement of the latter.

$x^2 + dy^2$

with d ranging over primes in certain congruence classes. The deduction of Theorem 1.4 from Theorem 5.1 is short and is given immediately after the statement of the latter.

The proof of Theorem 5.1 is via the second moment method. We divide the computations that arise into four separate technical propositions, Propositions 5.2, 5.3, 5.4 and 5.5. The synthesis of these propositions to give a proof of Theorem 5.1 is accomplished in Section 6.

The final sections of the main part of the paper are devoted to the proofs of these four technical propositions. Proposition 5.5 is a statement about averages of certain

![]() $L(1,\chi )$

, and we handle it first, in Section 7. The remaining three results all require some background on class group L-functions, and Section 8 provides an overview and references for the necessary material. Finally, the proofs of Propositions 5.2, 5.3 and 5.4 are given in Sections 9, 10 and 11, respectively.

$L(1,\chi )$

, and we handle it first, in Section 7. The remaining three results all require some background on class group L-functions, and Section 8 provides an overview and references for the necessary material. Finally, the proofs of Propositions 5.2, 5.3 and 5.4 are given in Sections 9, 10 and 11, respectively.

Sections 8, 9 and 10 use Selberg’s techniques [Reference Selberg16]. There is no particularly convenient reference for what we require, so we provide full details. The more standard parts of this may be found in Appendix A.

2 The upper and lower bounds imply the main theorem

In this section, we show how Theorem 1.1 follows from Theorems 1.3 and 1.4.

Suppose, as in the statement of Theorem 1.1, that

![]() $\Delta = (\log N)^{\log 2} 2^{\alpha \sqrt {\log \log N}}$

. It is enough to prove the result for

$\Delta = (\log N)^{\log 2} 2^{\alpha \sqrt {\log \log N}}$

. It is enough to prove the result for

the result for all

![]() $\alpha $

follows from this case and the fact that

$\alpha $

follows from this case and the fact that

Suppose henceforth that (2.1) holds.

Let

![]() $k^-$

be defined as the solution to

$k^-$

be defined as the solution to

![]() $\Delta = k^3 2^k$

and

$\Delta = k^3 2^k$

and

![]() $k^+$

as the solution to

$k^+$

as the solution to

![]() $\Delta = 2^k/k^4$

. Then, one may check that

$\Delta = 2^k/k^4$

. Then, one may check that

In particular, by the assumption (2.1), we see that

![]() $|k^{\pm } - k_0| \leq 2 k_0^{3/5}$

.

$|k^{\pm } - k_0| \leq 2 k_0^{3/5}$

.

For k in the range

![]() $k_0-2 k_0^{3/5} \leq k \leq k^-$

, Theorem 1.4 shows that the number of integers in

$k_0-2 k_0^{3/5} \leq k \leq k^-$

, Theorem 1.4 shows that the number of integers in

![]() ${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

that may be represented as

${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

that may be represented as

![]() $x^2+dy^2$

with

$x^2+dy^2$

with

![]() $d\leq \Delta $

is

$d\leq \Delta $

is

Stirling’s formula and the approximation

![]() $1 -x = \exp (-x -\frac {x^2}{2} + O(x^3))$

with

$1 -x = \exp (-x -\frac {x^2}{2} + O(x^3))$

with

![]() $x = 1 - \frac {k_0}{k}$

(

$x = 1 - \frac {k_0}{k}$

(

![]() $ = O(k_0^{-2/5})$

) show in this range of k that

$ = O(k_0^{-2/5})$

) show in this range of k that

$$ \begin{align} \frac{k_0^k}{k!} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi k_0}} \exp\Big( k_0 - \frac{(k_0-k)^2}{2k_0} + O\big( k_0^{-1/5}\big) \Big) \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{k_0^k}{k!} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi k_0}} \exp\Big( k_0 - \frac{(k_0-k)^2}{2k_0} + O\big( k_0^{-1/5}\big) \Big) \end{align} $$

so that using Lemma 1.2, we may see that the quantity in (2.2) is

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{N}{\sqrt{2\pi k_0} } \exp\Big( -\frac{(k-k_0)^2}{2k_0}\Big) \Big(1 + O\Big( \frac{1}{\log k_0} \Big) \Big) + O\big(N k_0^{-3/4}\big). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{N}{\sqrt{2\pi k_0} } \exp\Big( -\frac{(k-k_0)^2}{2k_0}\Big) \Big(1 + O\Big( \frac{1}{\log k_0} \Big) \Big) + O\big(N k_0^{-3/4}\big). \end{align*} $$

Summing over all k in this range, we conclude that the number of integers

![]() $n\leq N$

that may be written as

$n\leq N$

that may be written as

![]() $x^2+dy^2$

with

$x^2+dy^2$

with

![]() $d\leq \Delta $

is at least

$d\leq \Delta $

is at least

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{N}{\sqrt{2\pi k_0}} \sum_{k_0 - 2k_0^{3/5} \leq k \leq k^- } \exp\Big( - \frac{(k-k_0)^2}{2k_0}\Big) + O\Big(\frac{N}{\log k_0} \Big) = (\Phi(\alpha) +o(1)) N, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{N}{\sqrt{2\pi k_0}} \sum_{k_0 - 2k_0^{3/5} \leq k \leq k^- } \exp\Big( - \frac{(k-k_0)^2}{2k_0}\Big) + O\Big(\frac{N}{\log k_0} \Big) = (\Phi(\alpha) +o(1)) N, \end{align*} $$

upon approximating the sum by the corresponding integral. This shows the lower bound implicit in Theorem 1.1.

To obtain the corresponding upper bound, note that for k in the range

![]() $k^+ \leq k \leq k_0+2k_0^{3/5}$

, Theorem 1.3 shows that the number of integers in

$k^+ \leq k \leq k_0+2k_0^{3/5}$

, Theorem 1.3 shows that the number of integers in

![]() ${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

that cannot be represented as

${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

that cannot be represented as

![]() $x^2+dy^2$

with

$x^2+dy^2$

with

![]() $d\leq \Delta $

is

$d\leq \Delta $

is

![]() $|{\mathcal A}(N,k)| + O(N/k_0)$

. Using Lemma 1.2 and Stirling’s formula as above, this is

$|{\mathcal A}(N,k)| + O(N/k_0)$

. Using Lemma 1.2 and Stirling’s formula as above, this is

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{N}{\sqrt{2\pi k_0} } \exp\Big( -\frac{(k-k_0)^2}{2k_0}\Big) \Big(1 + O\big( k_0^{-1/5} \big) \Big) + O\big(Nk_0^{-1}\big). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{N}{\sqrt{2\pi k_0} } \exp\Big( -\frac{(k-k_0)^2}{2k_0}\Big) \Big(1 + O\big( k_0^{-1/5} \big) \Big) + O\big(Nk_0^{-1}\big). \end{align*} $$

Summing over all k in this range, we conclude the number of integers up to N that cannot be represented as

![]() $x^2+dy^2$

with

$x^2+dy^2$

with

![]() $d\leq \Delta $

is at least

$d\leq \Delta $

is at least

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{N}{\sqrt{2\pi k_0}} \sum_{k^+ \leq k \leq k_0 +2k_0^{3/5} } \exp\Big( - \frac{(k-k_0)^2}{2k_0}\Big) + O\big(N k_0^{-1/5} \big) = (1-\Phi(\alpha) +o(1)) N. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{N}{\sqrt{2\pi k_0}} \sum_{k^+ \leq k \leq k_0 +2k_0^{3/5} } \exp\Big( - \frac{(k-k_0)^2}{2k_0}\Big) + O\big(N k_0^{-1/5} \big) = (1-\Phi(\alpha) +o(1)) N. \end{align*} $$

This implies the upper bound implicit in Theorem 1.1 and completes the proof.

3 Background on quadratic forms

For the theory in the rest of this section, good resources are [Reference Cox5], [Reference Davenport6], [Reference Iwaniec and Kowalski13, Chapter 22] or [Reference Zagier19].

3.1 Fundamental discriminants and characters

A fundamental discriminant is an integer D of the following type: either (i)

![]() $D \equiv 1 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

and square-free or (ii)

$D \equiv 1 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

and square-free or (ii)

![]() $D = 4m$

with

$D = 4m$

with

![]() $m \equiv 2,3 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

and m square-free. Apart from

$m \equiv 2,3 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

and m square-free. Apart from

![]() $D = 1$

, these are precisely the discriminants of quadratic fields over

$D = 1$

, these are precisely the discriminants of quadratic fields over

![]() $\mathbf {Q}$

, and indeed the discriminant of

$\mathbf {Q}$

, and indeed the discriminant of

![]() $\mathbf {Q}(\sqrt {D})$

is D. Equivalently, if m is square-free, the quadratic field

$\mathbf {Q}(\sqrt {D})$

is D. Equivalently, if m is square-free, the quadratic field

![]() $\mathbf {Q}(\sqrt {m})$

has discriminant

$\mathbf {Q}(\sqrt {m})$

has discriminant

![]() $4m$

if

$4m$

if

![]() $m \equiv 2,3 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

and m if

$m \equiv 2,3 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

and m if

![]() $m \equiv 1\ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

.

$m \equiv 1\ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

.

Associated to the fundamental discriminant D is the primitive quadratic Dirichlet character

![]() $\chi _{D}(n) = (\frac {D}{n})$

, where the symbol here is the Kronecker symbol. This is defined to be completely multiplicative and specified on the primes by the following:

$\chi _{D}(n) = (\frac {D}{n})$

, where the symbol here is the Kronecker symbol. This is defined to be completely multiplicative and specified on the primes by the following:

-

• If p is an odd prime,

$\chi _{D}(p)= (\frac {D}{p})$

is the Legendre symbol;

$\chi _{D}(p)= (\frac {D}{p})$

is the Legendre symbol; -

•

$\chi _{D}(2) = 0$

if

$\chi _{D}(2) = 0$

if

$D \equiv 0 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

,

$D \equiv 0 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

,

$1$

if

$1$

if

$D \equiv 1 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 8)$

and

$D \equiv 1 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 8)$

and

$-1$

if

$-1$

if

$D \equiv 5\ (\operatorname {mod}\, 8)$

;

$D \equiv 5\ (\operatorname {mod}\, 8)$

; -

•

$\chi _{D}(-1) = \mbox {sgn}(D)$

.

$\chi _{D}(-1) = \mbox {sgn}(D)$

.

The Kronecker symbol

![]() $\chi _{D}$

is a primitive character of modulus

$\chi _{D}$

is a primitive character of modulus

![]() $|D|$

. It describes the splitting type of a prime p in the quadratic field

$|D|$

. It describes the splitting type of a prime p in the quadratic field

![]() $K=\mathbf {Q}(\sqrt {D})$

: A prime p splits in

$K=\mathbf {Q}(\sqrt {D})$

: A prime p splits in

![]() $\mathbf {Q}(\sqrt {D})$

if

$\mathbf {Q}(\sqrt {D})$

if

![]() $(\frac {D}{p})=1$

, remains inert if

$(\frac {D}{p})=1$

, remains inert if

![]() $(\frac {D}{p}) =-1$

and ramifies when

$(\frac {D}{p}) =-1$

and ramifies when

![]() $(\frac {D}{p})=0$

. Thus, the Dedekind zeta-function of the field K is given by

$(\frac {D}{p})=0$

. Thus, the Dedekind zeta-function of the field K is given by

and the number of ideals in

![]() $\mathcal {O}_K$

of norm n is

$\mathcal {O}_K$

of norm n is

$$ \begin{align*}(1 \ast \chi_{D})(n) = \sum_{\ell | n} \chi_{D}(\ell). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}(1 \ast \chi_{D})(n) = \sum_{\ell | n} \chi_{D}(\ell). \end{align*} $$

3.2 Positive definite forms and imaginary quadratic fields

Let

![]() $D < 0$

be a negative fundamental discriminant, and let

$D < 0$

be a negative fundamental discriminant, and let

![]() $K= \mathbf {Q}(\sqrt {D})$

denote the corresponding imaginary quadratic field.

$K= \mathbf {Q}(\sqrt {D})$

denote the corresponding imaginary quadratic field.

There is a well-known correspondence (going back to Gauss) between ideal classes in K and equivalence classes of positive definite binary quadratic forms of discriminant D. In particular, principal ideals in K are in correspondence with the principal binary quadratic form given by

![]() $x^2 + \frac {|D|}4 y^2$

(in the case

$x^2 + \frac {|D|}4 y^2$

(in the case

![]() $D\equiv 0 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

) and

$D\equiv 0 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

) and

![]() $x^2 + xy + \frac {1+|D|}{4} y^2$

(in the case

$x^2 + xy + \frac {1+|D|}{4} y^2$

(in the case

![]() $D \equiv 1 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

so that

$D \equiv 1 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

so that

![]() $|D|=-D \equiv 3 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

).

$|D|=-D \equiv 3 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

).

A key object of interest for us is

which counts the number of principal ideals in

![]() ${\mathcal O}_K$

of norm n. If

${\mathcal O}_K$

of norm n. If

![]() $D\equiv 0 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

, then a principal ideal

$D\equiv 0 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

, then a principal ideal

![]() ${\mathfrak a}$

of norm n may be written as

${\mathfrak a}$

of norm n may be written as

![]() $(a+b\sqrt {D/4})$

and corresponds to two representations of n by the principal form

$(a+b\sqrt {D/4})$

and corresponds to two representations of n by the principal form

![]() $x^2+ \frac {|D|}{4} y^2$

, namely

$x^2+ \frac {|D|}{4} y^2$

, namely

![]() $n= (\pm a)^2 + \frac {|D|}{4} (\pm b)^2$

(with the exception of

$n= (\pm a)^2 + \frac {|D|}{4} (\pm b)^2$

(with the exception of

![]() $D=-4$

, where it corresponds to

$D=-4$

, where it corresponds to

![]() $4$

representations by the principal form

$4$

representations by the principal form

![]() $x^2+y^2$

). Similarly, if

$x^2+y^2$

). Similarly, if

![]() $D\equiv 1\ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

, a principal ideal

$D\equiv 1\ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

, a principal ideal

![]() ${\mathfrak a}$

of norm n may be written as

${\mathfrak a}$

of norm n may be written as

![]() $(a + b \frac {1+\sqrt {D}}{2})$

and corresponds to two representations of n by the principal form

$(a + b \frac {1+\sqrt {D}}{2})$

and corresponds to two representations of n by the principal form

![]() $x^2 +xy + \frac {1+|D|}{4} y^2$

(with the exception of

$x^2 +xy + \frac {1+|D|}{4} y^2$

(with the exception of

![]() $D=-3$

, where it corresponds to

$D=-3$

, where it corresponds to

![]() $6$

representations by the principal form

$6$

representations by the principal form

![]() $x^2+xy+y^2$

).

$x^2+xy+y^2$

).

We remark that

since

![]() $(1*\chi _D)(n)$

counts all ideals with norm n, and that each ideal of norm n corresponds to two (or

$(1*\chi _D)(n)$

counts all ideals with norm n, and that each ideal of norm n corresponds to two (or

![]() $4$

when

$4$

when

![]() $D=-4$

, or

$D=-4$

, or

![]() $6$

when

$6$

when

![]() $D=-3$

) representations of n by some equivalence class of binary quadratic forms of discriminant D.

$D=-3$

) representations of n by some equivalence class of binary quadratic forms of discriminant D.

To isolate the principal ideals of norm n, we shall use class group characters. Let

![]() $C_K$

denote the ideal class group of K, and denote by

$C_K$

denote the ideal class group of K, and denote by

![]() $h_K$

its size which is the class number of K. A class group character is a homomorphism

$h_K$

its size which is the class number of K. A class group character is a homomorphism

![]() $\psi : C_K \to \mathbf {C}^{\times }$

. We may think of such class group characters as maps

$\psi : C_K \to \mathbf {C}^{\times }$

. We may think of such class group characters as maps

satisfying

![]() $\psi ({\mathfrak a }{\mathfrak b}) = \psi ({\mathfrak a}) \psi ({\mathfrak b})$

and

$\psi ({\mathfrak a }{\mathfrak b}) = \psi ({\mathfrak a}) \psi ({\mathfrak b})$

and

![]() $\psi ((\lambda )) = 1$

for every nonzero principal ideal

$\psi ((\lambda )) = 1$

for every nonzero principal ideal

![]() $(\lambda )$

. We denote the dual group of class group characters by

$(\lambda )$

. We denote the dual group of class group characters by

![]() ${\widehat C}_K$

.

${\widehat C}_K$

.

If

![]() $\psi \in {\widehat C}_K$

is a class group character, then we define

$\psi \in {\widehat C}_K$

is a class group character, then we define

$$ \begin{align} r(n,\psi) = r(n,\psi; D) = \sum_{N(\mathfrak a)=n} \psi({\mathfrak a}). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} r(n,\psi) = r(n,\psi; D) = \sum_{N(\mathfrak a)=n} \psi({\mathfrak a}). \end{align} $$

Notice that

![]() ${\widehat C}_K$

always includes the principal character

${\widehat C}_K$

always includes the principal character

![]() $\psi _0$

given by

$\psi _0$

given by

![]() $\psi _0(\mathfrak a) =1$

for all ideals

$\psi _0(\mathfrak a) =1$

for all ideals

![]() ${\mathfrak a}$

. In this case,

${\mathfrak a}$

. In this case,

$$ \begin{align} r(n,\psi_0) = \sum_{N(\mathfrak a)=n} 1 = (1*\chi_D)(n). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} r(n,\psi_0) = \sum_{N(\mathfrak a)=n} 1 = (1*\chi_D)(n). \end{align} $$

The orthogonality relations for characters now allow us to express

![]() $R_D(n)$

in terms of

$R_D(n)$

in terms of

![]() $r(n,\psi )$

: namely,

$r(n,\psi )$

: namely,

$$ \begin{align} R_D(n) = \frac{1}{h_K} \sum_{\psi \in {\widehat C}_K} r(n, \psi). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} R_D(n) = \frac{1}{h_K} \sum_{\psi \in {\widehat C}_K} r(n, \psi). \end{align} $$

With these preliminaries in place, we postpone a more detailed discussion of class group characters to Section 8.

3.3 Representation by

$x^2+dy^2$

$x^2+dy^2$

We now relate the concepts of the previous section to our specific problem of representing integers by the quadratic forms

![]() $x^2+dy^2$

. We will restrict attention to square-free integers d, which is sufficient for our purposes. The problem of representing integers by

$x^2+dy^2$

. We will restrict attention to square-free integers d, which is sufficient for our purposes. The problem of representing integers by

![]() $x^2+dy^2$

is naturally related to arithmetic in the field

$x^2+dy^2$

is naturally related to arithmetic in the field

![]() $K=\mathbf {Q}(\sqrt {-d}) = \mathbf {Q}(\sqrt {D})$

, where D denotes the fundamental discriminant

$K=\mathbf {Q}(\sqrt {-d}) = \mathbf {Q}(\sqrt {D})$

, where D denotes the fundamental discriminant

$$ \begin{align} D = \begin{cases} -4d &\text{ if } d \equiv 1,2 \ (\operatorname{mod}\, 4), \\ -d & \text{ if } d \equiv 3\ (\operatorname{mod}\, 4). \end{cases} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} D = \begin{cases} -4d &\text{ if } d \equiv 1,2 \ (\operatorname{mod}\, 4), \\ -d & \text{ if } d \equiv 3\ (\operatorname{mod}\, 4). \end{cases} \end{align} $$

Henceforth in the paper, we will adopt the following notational conventions. Unless explicitly stated otherwise, whenever we write d we have in mind a square-free integer, and corresponding to such d will be the fundamental discriminant D given in (3.5), and the imaginary quadratic field

![]() $K = \mathbf {Q}(\sqrt {-d}) = \mathbf {Q}(\sqrt {D})$

. Of course, K and D depend on d, but we will not indicate this explicitly. Sometimes, we will additionally have a second positive square-free number

$K = \mathbf {Q}(\sqrt {-d}) = \mathbf {Q}(\sqrt {D})$

. Of course, K and D depend on d, but we will not indicate this explicitly. Sometimes, we will additionally have a second positive square-free number

![]() $d'$

, and

$d'$

, and

![]() $K', D'$

will be associated to it in the same way.

$K', D'$

will be associated to it in the same way.

Lemma 3.1. Let

![]() $d \ge 1$

be square-free, and let

$d \ge 1$

be square-free, and let

![]() $D, K$

be associated to d as above.

$D, K$

be associated to d as above.

-

1. If

$d \equiv 1$

or

$d \equiv 1$

or

$2 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

, then the number of representations of n by the quadratic form

$2 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

, then the number of representations of n by the quadratic form

$x^2 + dy^2$

equals

$x^2 + dy^2$

equals

$2R_D(n)$

, with the exception of the special case

$2R_D(n)$

, with the exception of the special case

$d=1$

where it equals

$d=1$

where it equals

$4 R_{-4}(n)$

.

$4 R_{-4}(n)$

. -

2. If

$d\equiv 3\ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

, then the number of representations of n by the quadratic form

$d\equiv 3\ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

, then the number of representations of n by the quadratic form

$x^2+dy^2$

is at most

$x^2+dy^2$

is at most

$2 R_D(n)$

, with the exception of the special case

$2 R_D(n)$

, with the exception of the special case

$d=3$

where it is at most

$d=3$

where it is at most

$6R_{-3}(n)$

.

$6R_{-3}(n)$

. -

3. If

$d \equiv 7 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 8)$

and n is odd, then the number of representations of n by the quadratic form

$d \equiv 7 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 8)$

and n is odd, then the number of representations of n by the quadratic form

$x^2+dy^2$

equals

$x^2+dy^2$

equals

$2R_D(n)$

.

$2R_D(n)$

.

Proof. If

![]() $d\equiv 1, 2 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

, we have

$d\equiv 1, 2 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

, we have

![]() $D= -4d$

, and the quadratic form

$D= -4d$

, and the quadratic form

![]() $x^2 +dy^2$

is the principal form of discriminant D. The result (1) now follows from our discussion in Section 3.2.

$x^2 +dy^2$

is the principal form of discriminant D. The result (1) now follows from our discussion in Section 3.2.

If

![]() $d\equiv 3 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

, then

$d\equiv 3 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

, then

![]() $D=-d$

, and the principal form of discriminant D is

$D=-d$

, and the principal form of discriminant D is

![]() $x^2+xy + \frac {1+d}{4} y^2$

. The identity

$x^2+xy + \frac {1+d}{4} y^2$

. The identity

shows that the representations of n as

![]() $x^2+dy^2$

are in bijective correspondence with the representations of n as

$x^2+dy^2$

are in bijective correspondence with the representations of n as

![]() $X^2 + XY + \frac {1+d}{4} Y^2$

with Y even. Since the total number of representations of n as

$X^2 + XY + \frac {1+d}{4} Y^2$

with Y even. Since the total number of representations of n as

![]() $X^2+XY +\frac {1+d}{4} Y^2$

(ignoring whether Y is even or odd) equals

$X^2+XY +\frac {1+d}{4} Y^2$

(ignoring whether Y is even or odd) equals

![]() $2R_D(n)$

(or

$2R_D(n)$

(or

![]() $6R_{-3}(n)$

in the exceptional case

$6R_{-3}(n)$

in the exceptional case

![]() $d=-3$

), the upper bound stated in (2) follows.

$d=-3$

), the upper bound stated in (2) follows.

Finally, if

![]() $d\equiv 7 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 8)$

and n is odd, then

$d\equiv 7 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 8)$

and n is odd, then

![]() $\frac {1+d}{4}$

is even, and so any representation of n as

$\frac {1+d}{4}$

is even, and so any representation of n as

![]() $X^2+XY+ \frac {1+d}{4} Y^2$

must necessarily have Y being even. Thus, in this case the representations of n by

$X^2+XY+ \frac {1+d}{4} Y^2$

must necessarily have Y being even. Thus, in this case the representations of n by

![]() $X^2+XY + \frac {1+d}{4} Y^2$

equal the representations of n by

$X^2+XY + \frac {1+d}{4} Y^2$

equal the representations of n by

![]() $x^2+dy^2$

, and assertion (3) follows.

$x^2+dy^2$

, and assertion (3) follows.

4 Proof of the upper bound

In this section, we prove Theorem 1.3. It will follow from the following proposition.

Proposition 4.1. Let N be large and k an integer in the range (1.1). Let d be a square-free integer with

![]() $d\leq \log N$

. Then the number of integers

$d\leq \log N$

. Then the number of integers

![]() $n \in {\mathcal A}(N,k)$

that are represented by

$n \in {\mathcal A}(N,k)$

that are represented by

![]() $x^2+dy^2$

is

$x^2+dy^2$

is

![]() $\ll \frac {N}{2^k} (\log \log N)^3$

.

$\ll \frac {N}{2^k} (\log \log N)^3$

.

Before proving the proposition, let us deduce Theorem 1.3. Note that if

![]() $d=d_1 d_2^2$

with

$d=d_1 d_2^2$

with

![]() $d_1$

square-free, then an integer represented by

$d_1$

square-free, then an integer represented by

![]() $x^2 +dy^2$

is automatically represented by

$x^2 +dy^2$

is automatically represented by

![]() $x^2 +d_1 y^2$

.

$x^2 +d_1 y^2$

.

Using Proposition 4.1, it follows that the number of integers in

![]() ${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

that are represented by

${\mathcal A}(N,k)$

that are represented by

![]() $x^2+dy^2$

for some d,

$x^2+dy^2$

for some d,

![]() $1\leq d\leq \Delta $

is

$1\leq d\leq \Delta $

is

since

![]() $\Delta \leq 2^k/k^4$

. This establishes Theorem 1.3.

$\Delta \leq 2^k/k^4$

. This establishes Theorem 1.3.

To prove Proposition 4.1, we require the following simple lemma.

Lemma 4.2. Let D be any fundamental discriminant apart from

![]() $D=1$

. For all

$D=1$

. For all

![]() $x\geq 1$

, we have

$x\geq 1$

, we have

![]() $\sum _{n\leq x} (1*\chi _D)(n) \ll x\log |D|$

.

$\sum _{n\leq x} (1*\chi _D)(n) \ll x\log |D|$

.

Proof. Suppose first that

![]() $x\leq |D|^2$

. Since

$x\leq |D|^2$

. Since

![]() $(1*\chi _D)(n) \leq \tau (n)$

(the number of divisors of n), the sum in question is

$(1*\chi _D)(n) \leq \tau (n)$

(the number of divisors of n), the sum in question is

![]() $\leq \sum _{n\leq x} \tau (n) \ll x \log (x+1) \ll x\log |D|$

.

$\leq \sum _{n\leq x} \tau (n) \ll x \log (x+1) \ll x\log |D|$

.

Now, suppose that

![]() $x> |D|^2$

, and note that

$x> |D|^2$

, and note that

$$ \begin{align*}(1*\chi_D)(n) = \sum_{ab =n} \chi_D(b) = \sum_{\substack{ab =n \\ b \leq |D|}}\chi_D(b) + \sum_{\substack{ab=n \\ b>|D|}} \chi_D(b). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}(1*\chi_D)(n) = \sum_{ab =n} \chi_D(b) = \sum_{\substack{ab =n \\ b \leq |D|}}\chi_D(b) + \sum_{\substack{ab=n \\ b>|D|}} \chi_D(b). \end{align*} $$

Therefore,

$$ \begin{align} \sum_{n\leq x} (1*\chi_D)(n) = \sum_{b\leq |D|} \chi_D(b) \sum_{a\leq x/b} 1 + \sum_{a\leq x/|D|} \sum_{|D| < b\leq x/a} \chi_D(b). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \sum_{n\leq x} (1*\chi_D)(n) = \sum_{b\leq |D|} \chi_D(b) \sum_{a\leq x/b} 1 + \sum_{a\leq x/|D|} \sum_{|D| < b\leq x/a} \chi_D(b). \end{align} $$

The first term on the right side of (4.1) contributes

$$ \begin{align*}\sum_{b\leq |D|} \chi_D(b) \Big( \frac{x}{b}+O(1)\Big) \ll \sum_{b\leq |D|} \Big( \frac{x}{b}+1\Big) \ll x \log |D|. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\sum_{b\leq |D|} \chi_D(b) \Big( \frac{x}{b}+O(1)\Big) \ll \sum_{b\leq |D|} \Big( \frac{x}{b}+1\Big) \ll x \log |D|. \end{align*} $$

Since

![]() $\chi _D$

is a nonprincipal character to the modulus

$\chi _D$

is a nonprincipal character to the modulus

![]() $|D|$

, it sums to zero over any interval of length D, and therefore

$|D|$

, it sums to zero over any interval of length D, and therefore

![]() $|\sum _{|D| < b\leq x/a} \chi _D(b)| \leq |D|$

. It follows that the second term on the right side of (4.1) contributes

$|\sum _{|D| < b\leq x/a} \chi _D(b)| \leq |D|$

. It follows that the second term on the right side of (4.1) contributes

![]() $\ll |D| \sum _{a\leq x/|D|} 1 \ll x$

, and the lemma follows.

$\ll |D| \sum _{a\leq x/|D|} 1 \ll x$

, and the lemma follows.

Proof of Proposition 4.1

Let d be square-free with

![]() $d \leq \log N$

, and let D be the fundamental discriminant associated to it (as given in (3.5)). Write

$d \leq \log N$

, and let D be the fundamental discriminant associated to it (as given in (3.5)). Write

![]() $\mathcal {R} = \mathcal {R}(d)$

for the set of all r such that the primes dividing r either divide

$\mathcal {R} = \mathcal {R}(d)$

for the set of all r such that the primes dividing r either divide

![]() $|D|$

or appear to exponent at least

$|D|$

or appear to exponent at least

![]() $2$

in the prime factorization of r. Suppose

$2$

in the prime factorization of r. Suppose

![]() $n \in {\mathcal A}(N,k)$

is an integer that can be expressed as

$n \in {\mathcal A}(N,k)$

is an integer that can be expressed as

![]() $x^2+dy^2$

. Write n uniquely as

$x^2+dy^2$

. Write n uniquely as

![]() $rs$

, where

$rs$

, where

![]() $(r,s)=1$

, s is square-free and composed of primes not dividing

$(r,s)=1$

, s is square-free and composed of primes not dividing

![]() $|D|$

and

$|D|$

and

![]() $r \in \mathcal {R}$

. We have that

$r \in \mathcal {R}$

. We have that

![]() $\Omega (r) \leq k$

and note that

$\Omega (r) \leq k$

and note that

![]() $\Omega (s) = k-\Omega (r)$

.

$\Omega (s) = k-\Omega (r)$

.

By Lemma 3.1 and (3.1), we know that if n is representable by

![]() $x^2+dy^2$

, then

$x^2+dy^2$

, then

![]() $(1*\chi _D)(n) \geq R_D(n)>0$

. Since

$(1*\chi _D)(n) \geq R_D(n)>0$

. Since

![]() $(1*\chi _D)$

is a nonnegative multiplicative function, it follows that

$(1*\chi _D)$

is a nonnegative multiplicative function, it follows that

![]() $(1*\chi _D)(s)> 0$

or, equivalently, that every prime

$(1*\chi _D)(s)> 0$

or, equivalently, that every prime

![]() $p|s$

satisfies

$p|s$

satisfies

![]() $\chi _D(p)=1$

and therefore

$\chi _D(p)=1$

and therefore

![]() $(1*\chi _D)(s) = 2^{\Omega (s)}$

. Thus,

$(1*\chi _D)(s) = 2^{\Omega (s)}$

. Thus,

$$ \begin{align*} \sum_{\substack{ n \in {\mathcal A}(N,k) \\ n =x^2 +dy^2}} 1 \leq \sum_{\substack{ rs \in {\mathcal A}(N,k)}} 2^{-\Omega(s)} (1*\chi_D)(s) & = 2^{-k} \sum_{ rs \in {\mathcal A}(N,k)} 2^{\Omega(r)} (1*\chi_D)(s) \\ & \leq 2^{-k} \sum_{\substack{ r \in \mathcal{R} \\ \Omega(r) \leq k \\ r \leq N} } 2^{\Omega(r)} \sum_{s \leq N/r} (1*\chi_D)(s), \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \sum_{\substack{ n \in {\mathcal A}(N,k) \\ n =x^2 +dy^2}} 1 \leq \sum_{\substack{ rs \in {\mathcal A}(N,k)}} 2^{-\Omega(s)} (1*\chi_D)(s) & = 2^{-k} \sum_{ rs \in {\mathcal A}(N,k)} 2^{\Omega(r)} (1*\chi_D)(s) \\ & \leq 2^{-k} \sum_{\substack{ r \in \mathcal{R} \\ \Omega(r) \leq k \\ r \leq N} } 2^{\Omega(r)} \sum_{s \leq N/r} (1*\chi_D)(s), \end{align*} $$

where in the last step we used the nonnegativity of

![]() $1*\chi _D$

to take the sum over all

$1*\chi _D$

to take the sum over all

![]() $s \leq N/r$

. Applying Lemma 4.2 to the sum over s, we obtain

$s \leq N/r$

. Applying Lemma 4.2 to the sum over s, we obtain

$$ \begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{ n \in {\mathcal A}(N,k) \\ n =x^2 +dy^2}} 1 \ll \frac{N}{2^k} \log |D| \sum_{\substack{r \in \mathcal{R} \\ \Omega(r) \leq k} } \frac{2^{\Omega(r)}}{r}. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{ n \in {\mathcal A}(N,k) \\ n =x^2 +dy^2}} 1 \ll \frac{N}{2^k} \log |D| \sum_{\substack{r \in \mathcal{R} \\ \Omega(r) \leq k} } \frac{2^{\Omega(r)}}{r}. \end{align*} $$

Now,

$$\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{r \in \mathcal{R} \\ \Omega(r) \leq k}} \frac{2^{\Omega(r)}}{r} \leq \prod_{p| |D|} \Big( 1 + \sum_{j=1}^{k} \frac{2^j}{p^j} \Big) \prod_{p \nmid |D|} \Big(1 +\sum_{j=2}^{k} \frac{2^j}{p^j}\Big) \ll k \prod_{p| |D|} \Big(1 + \frac 2p\Big) \ll k (\log \log |D|)^2, \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{r \in \mathcal{R} \\ \Omega(r) \leq k}} \frac{2^{\Omega(r)}}{r} \leq \prod_{p| |D|} \Big( 1 + \sum_{j=1}^{k} \frac{2^j}{p^j} \Big) \prod_{p \nmid |D|} \Big(1 +\sum_{j=2}^{k} \frac{2^j}{p^j}\Big) \ll k \prod_{p| |D|} \Big(1 + \frac 2p\Big) \ll k (\log \log |D|)^2, \end{align*}$$

where the factor k above arises from the prime

![]() $p=2$

. Since

$p=2$

. Since

![]() $k\ll \log \log N$

and

$k\ll \log \log N$

and

![]() $|D|\leq \log N$

, the proposition follows.

$|D|\leq \log N$

, the proposition follows.

5 Plan of the proof of the lower bound

We now turn to the proof of Theorem 1.4, which constitutes the bulk of the paper. Let N be large, recall that k is an integer in the range (1.1), and suppose in all that follows that

We wish to bound the exceptional integers

![]() $n \in {\mathcal A}(N,k)$

that cannot be represented as

$n \in {\mathcal A}(N,k)$

that cannot be represented as

![]() $x^2+dy^2$

with d below

$x^2+dy^2$

with d below

![]() $\Delta $

. In fact, we shall consider only representations by such quadratic forms when d is a prime lying in a suitable residue class and show that most integers can be represented even with this further constraint.

$\Delta $

. In fact, we shall consider only representations by such quadratic forms when d is a prime lying in a suitable residue class and show that most integers can be represented even with this further constraint.

To state our results more precisely, we distinguish two cases according to whether the

![]() $2$

-adic valuation

$2$

-adic valuation

![]() $v_2(n)$

is

$v_2(n)$

is

![]() $0$

or

$0$

or

![]() $1$

(or in other words whether

$1$

(or in other words whether

![]() $n\equiv 1 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 2)$

or

$n\equiv 1 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 2)$

or

![]() $n \equiv 2 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

). Results for integers n that are multiples of

$n \equiv 2 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 4)$

). Results for integers n that are multiples of

![]() $4$

will be deduced easily from these cases. Thus, we define, for all

$4$

will be deduced easily from these cases. Thus, we define, for all

![]() $j =0$

,

$j =0$

,

![]() $1$

,

$1$

,

$$\begin{align*}{\mathcal A}_j(k) & = \{ v_2(n) = j, \ \ \Omega(n)=k\}, \\ {\mathcal A}_j(N,k) &= \{ n \leq N, \ \ n \in {\mathcal A}_j(k)\}. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}{\mathcal A}_j(k) & = \{ v_2(n) = j, \ \ \Omega(n)=k\}, \\ {\mathcal A}_j(N,k) &= \{ n \leq N, \ \ n \in {\mathcal A}_j(k)\}. \end{align*}$$

Observe that

and

Thus, from Lemma 1.2 we may deduce that for k satisfying

![]() $|k-k_0| \leq \frac 13 k_0$

we have

$|k-k_0| \leq \frac 13 k_0$

we have

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{A}_j(N,k) = 2^{-j-1}\frac{N}{\log N} \frac{k_0^{k}}{k!} \Big(1 + O\Big(\frac{1+|k-k_0|}{k_0}\Big)\Big). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{A}_j(N,k) = 2^{-j-1}\frac{N}{\log N} \frac{k_0^{k}}{k!} \Big(1 + O\Big(\frac{1+|k-k_0|}{k_0}\Big)\Big). \end{align} $$

Here, we recall that

![]() $k_0$

denotes

$k_0$

denotes

![]() $\log \log N$

.

$\log \log N$

.

To each case

![]() $j = 0,1$

we associate a set

$j = 0,1$

we associate a set

![]() $\mathcal {D}_j$

of primes. Below, we let W denote a parameter tending to infinity slowly with N; for definiteness, we set

$\mathcal {D}_j$

of primes. Below, we let W denote a parameter tending to infinity slowly with N; for definiteness, we set

![]() $W=\log \log \log N$

. With this choice of W, define

$W=\log \log \log N$

. With this choice of W, define

Here, as usual, D denotes the fundamental discriminant associated to d as given in (3.5). Thus,

![]() $D=-d$

for

$D=-d$

for

![]() $d\in {\mathcal D}_0$

and since

$d\in {\mathcal D}_0$

and since

![]() $D\equiv 1 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 8)$

, we have

$D\equiv 1 \ (\operatorname {mod}\, 8)$

, we have

![]() $\chi _D(2) =1$

automatically. If d is in

$\chi _D(2) =1$

automatically. If d is in

![]() ${\mathcal D}_1$

, then

${\mathcal D}_1$

, then

![]() $D= -4d$

, and here

$D= -4d$

, and here

![]() $\chi _D(2)=0$

. The primes in

$\chi _D(2)=0$

. The primes in

![]() ${\mathcal D}_0$

lie in

${\mathcal D}_0$

lie in

![]() $\prod _{3\leq p \leq W} \frac {p-1}{2}$

reduced residue classes

$\prod _{3\leq p \leq W} \frac {p-1}{2}$

reduced residue classes

![]() $(\operatorname {mod}\, 8\prod _{3\leq p\leq W} p)$

, while those in

$(\operatorname {mod}\, 8\prod _{3\leq p\leq W} p)$

, while those in

![]() ${\mathcal D}_1$

lie in

${\mathcal D}_1$

lie in

![]() $\prod _{3\leq p \leq W} \frac {p-1}{2}$

reduced residue classes

$\prod _{3\leq p \leq W} \frac {p-1}{2}$

reduced residue classes

![]() $(\operatorname {mod}\, 4\prod _{3\leq p\leq W} p)$

. Since W is suitably small, a simple application of the prime number theorem in arithmetic progressions gives

$(\operatorname {mod}\, 4\prod _{3\leq p\leq W} p)$

. Since W is suitably small, a simple application of the prime number theorem in arithmetic progressions gives

In particular, since

![]() $W = \log \log \log N$

, and since

$W = \log \log \log N$

, and since

we have the crude bounds

We are now ready to state our result on representing integers in

![]() ${\mathcal A}_j(N,k)$

using the binary quadratic forms

${\mathcal A}_j(N,k)$

using the binary quadratic forms

![]() $x^2 + dy^2$

with

$x^2 + dy^2$

with

![]() $d\in {\mathcal D}_j$

. From this result, we shall swiftly deduce Theorem 1.4.

$d\in {\mathcal D}_j$

. From this result, we shall swiftly deduce Theorem 1.4.

Theorem 5.1. Suppose that N is large, k is an integer in the range

where

![]() $k_0 := \log \log N$

, and that

$k_0 := \log \log N$

, and that

![]() $k^3 2^k \leq \Delta \leq \log N$

. For

$k^3 2^k \leq \Delta \leq \log N$

. For

![]() $j = 0,1$

, let

$j = 0,1$

, let

![]() ${\mathcal E}_j(N,k)$

denote the exceptional set of integers in

${\mathcal E}_j(N,k)$

denote the exceptional set of integers in

![]() ${\mathcal A}_j(N,k)$

that cannot be expressed as

${\mathcal A}_j(N,k)$

that cannot be expressed as

![]() $x^2+dy^2$

for some

$x^2+dy^2$

for some

![]() $d\in {\mathcal D}_j$

. Then we have

$d\in {\mathcal D}_j$

. Then we have

Deducing Theorem 1.4 from Theorem 5.1.

Extracting the largest power of

![]() $4$

, we see that every

$4$

, we see that every

![]() $n \in {\mathcal A}(N,k)$

may be written uniquely as

$n \in {\mathcal A}(N,k)$

may be written uniquely as

![]() $n= 4^m r$

, where r is either in

$n= 4^m r$

, where r is either in

![]() ${\mathcal A}_0(N/4^m, k-2m)$

or in

${\mathcal A}_0(N/4^m, k-2m)$

or in

![]() ${\mathcal A}_1(N/4^m, k-2m)$

. Further, if r can be represented as

${\mathcal A}_1(N/4^m, k-2m)$

. Further, if r can be represented as

![]() $x^2 +dy^2$

with

$x^2 +dy^2$

with

![]() $d\leq \Delta $

, then plainly so can

$d\leq \Delta $

, then plainly so can

![]() $n= 4^m r$

. Thus,

$n= 4^m r$

. Thus,

First, let us dispense with the terms

![]() $m \geq \log k_0$

. Bounding

$m \geq \log k_0$

. Bounding

![]() $|{\mathcal E}_0(N/4^m, k-2m)| + |{\mathcal E}_1(N/4^m, k-2m)|$

trivially by

$|{\mathcal E}_0(N/4^m, k-2m)| + |{\mathcal E}_1(N/4^m, k-2m)|$

trivially by

![]() $N/4^m$

, we see that these terms contribute

$N/4^m$

, we see that these terms contribute

![]() $\ll \sum _{m\geq \log k_0} N/4^m \ll N/k_0$

, which is better than we need.

$\ll \sum _{m\geq \log k_0} N/4^m \ll N/k_0$

, which is better than we need.

For the terms with

![]() $m\leq \log k_0$

, we wish to use Theorem 5.1 to bound the quantity

$m\leq \log k_0$

, we wish to use Theorem 5.1 to bound the quantity

![]() $|{\mathcal E}_j (N/4^m, k-2m)|$

(for

$|{\mathcal E}_j (N/4^m, k-2m)|$

(for

![]() $j=0,1$

). We must check that the required conditions there hold. The condition on

$j=0,1$

). We must check that the required conditions there hold. The condition on

![]() $\Delta $

is automatic: Since

$\Delta $

is automatic: Since

![]() $\Delta $

is assumed to be

$\Delta $

is assumed to be

![]() $\geq k^3 2^k$

it is clearly also

$\geq k^3 2^k$

it is clearly also

![]() $\geq (k-2m)^3 2^{k-2m}$

. The main condition to check is the analogue of (5.5) which here reads

$\geq (k-2m)^3 2^{k-2m}$

. The main condition to check is the analogue of (5.5) which here reads

![]() $|(k-2m) - \log \log (N/4^m) | \leq 2 (\log \log (N/4^m))^{2/3}$

. To verify this, note that for

$|(k-2m) - \log \log (N/4^m) | \leq 2 (\log \log (N/4^m))^{2/3}$

. To verify this, note that for

![]() $m\leq \log k_0$

, one has

$m\leq \log k_0$

, one has

![]() $\log \log (N/4^m) = k_0 +O(1)$

, and so the left side above is

$\log \log (N/4^m) = k_0 +O(1)$

, and so the left side above is

![]() $\leq |k_0 - k| + 2m + O(1) \leq k_0^{2/3} + 2\log k_0 + O(1)$

since k is in the range (1.1). Thus, we may apply Theorem 5.1, and conclude that

$\leq |k_0 - k| + 2m + O(1) \leq k_0^{2/3} + 2\log k_0 + O(1)$

since k is in the range (1.1). Thus, we may apply Theorem 5.1, and conclude that

Now, applying Lemma 1.2 we obtain

$$ \begin{align*} |{\mathcal A} (N/4^m, k-2m)| & \ll \frac{N}{4^m \log (N/4^m)} \frac{(\log \log (N/4^m))^{k-2m}}{(k-2m)!} \\ & \ll \frac{N}{4^m \log N} \frac{(\log \log N)^{k-2m}}{(k-2m)!} \ll \frac{N}{4^m \log N} \frac{k_0^{k}}{k!} \Big(\frac{k}{k_0}\Big)^{2m} \ll \frac{|{\mathcal A}(N,k)|}{4^m}, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} |{\mathcal A} (N/4^m, k-2m)| & \ll \frac{N}{4^m \log (N/4^m)} \frac{(\log \log (N/4^m))^{k-2m}}{(k-2m)!} \\ & \ll \frac{N}{4^m \log N} \frac{(\log \log N)^{k-2m}}{(k-2m)!} \ll \frac{N}{4^m \log N} \frac{k_0^{k}}{k!} \Big(\frac{k}{k_0}\Big)^{2m} \ll \frac{|{\mathcal A}(N,k)|}{4^m}, \end{align*} $$

where the final estimate holds since

![]() $k/k_0 = 1 +O(k_0^{-1/3})$

and

$k/k_0 = 1 +O(k_0^{-1/3})$

and

![]() $m\leq \log k_0$

so that

$m\leq \log k_0$

so that

![]() $(k/k_0)^{2m} \ll 1$

. We conclude that the contribution of the terms with

$(k/k_0)^{2m} \ll 1$

. We conclude that the contribution of the terms with

![]() $m \leq \log k_0$

may be bounded by

$m \leq \log k_0$

may be bounded by

$$ \begin{align*}\ll \sum_{m\leq \log k_0} 4^{-m} \Big( \frac{|{\mathcal A}(N,k)|}{\log k_0} + N k^{\varepsilon - 5/6}\Big) \ll \frac{|{\mathcal A}(N,k)|}{\log k_0} + N k_0^{-3/4}. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\ll \sum_{m\leq \log k_0} 4^{-m} \Big( \frac{|{\mathcal A}(N,k)|}{\log k_0} + N k^{\varepsilon - 5/6}\Big) \ll \frac{|{\mathcal A}(N,k)|}{\log k_0} + N k_0^{-3/4}. \end{align*} $$

Combining this estimate with our bound for the larger range of m, we complete the deduction of Theorem 1.4.

Theorem 5.1 will be deduced (in the next section) from the following four propositions which form the heart of our argument. Before stating these propositions, we introduce some notation that will be in place for the rest of our work. We shall factorize n as

![]() $n^{\flat } n^{\sharp }$

, where

$n^{\flat } n^{\sharp }$

, where

![]() $n^{\flat }$

is composed only of primes below W, and

$n^{\flat }$

is composed only of primes below W, and

![]() $n^{\sharp }$

is composed only of primes above W. Further, we define

$n^{\sharp }$

is composed only of primes above W. Further, we define

For each choice of

![]() $j=0$

or

$j=0$

or

![]() $1$

, we define

$1$

, we define

$$ \begin{align} F_j(n) = \frac{1}{|{\mathcal D}_j|} \sum_{d\in {\mathcal D}_j} \frac{|D|^{1/2}}{\pi \gamma_W} \frac{R_D(n)}{\tau(n^{\flat})}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} F_j(n) = \frac{1}{|{\mathcal D}_j|} \sum_{d\in {\mathcal D}_j} \frac{|D|^{1/2}}{\pi \gamma_W} \frac{R_D(n)}{\tau(n^{\flat})}. \end{align} $$

Note that if n cannot be represented as

![]() $x^2 +dy^2$

with

$x^2 +dy^2$

with

![]() $d\in {\mathcal D}_j$

, then

$d\in {\mathcal D}_j$

, then

![]() $R_D(n)=0$

for all

$R_D(n)=0$

for all

![]() $d\in {\mathcal D}_j$

and therefore

$d\in {\mathcal D}_j$

and therefore

![]() $F_j(n)=0$

. The proof is based on showing that for

$F_j(n)=0$

. The proof is based on showing that for

![]() $n\in {\mathcal A}_j(k)$

, the quantity

$n\in {\mathcal A}_j(k)$

, the quantity

![]() $F_j(n)$

is usually close to its expected value of

$F_j(n)$

is usually close to its expected value of

![]() $1$

, which is achieved by showing that

$1$

, which is achieved by showing that

![]() $(F_j(n)-1)^2$

is small on average over n. The four propositions below facilitate the calculation of this variance, which will be carried out in the next section.

$(F_j(n)-1)^2$

is small on average over n. The four propositions below facilitate the calculation of this variance, which will be carried out in the next section.

Proposition 5.2. Let N be large, and let k be an integer in the range (5.5). The following statements hold for either choice of

![]() $j=0$

or

$j=0$

or

![]() $1$

. Let d be an element in

$1$

. Let d be an element in

![]() ${\mathcal D}_j$

, and let D be the corresponding fundamental discriminant. Then

${\mathcal D}_j$

, and let D be the corresponding fundamental discriminant. Then

$$\begin{align*}\frac{|D|^{1/2}}{\pi \gamma_W} \sum_{n \in {\mathcal A}_j(k)} \frac{R_D(n)}{\tau(n^{\flat})} e^{-n/N} = \sum_{n\in {\mathcal A}_j(k)} e^{-n/N} + N O_{\varepsilon}\big( k_0^{\varepsilon - 5/6} + L(1,\chi_D)^{-1} k_0^{-2}\big), \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\frac{|D|^{1/2}}{\pi \gamma_W} \sum_{n \in {\mathcal A}_j(k)} \frac{R_D(n)}{\tau(n^{\flat})} e^{-n/N} = \sum_{n\in {\mathcal A}_j(k)} e^{-n/N} + N O_{\varepsilon}\big( k_0^{\varepsilon - 5/6} + L(1,\chi_D)^{-1} k_0^{-2}\big), \end{align*}$$

where

![]() $\gamma _W$

is as in (5.6).

$\gamma _W$

is as in (5.6).

Partial summation and (5.1) easily allow us to give an asymptotic for the sum

![]() $\sum _{n\in {\mathcal A}_j(k)} e^{-n/N}$

appearing above. Write

$\sum _{n\in {\mathcal A}_j(k)} e^{-n/N}$

appearing above. Write

$$\begin{align*}\sum_{n\in {\mathcal A}_j(k)} e^{-n/N} = \int^{\infty}_0 e^{-u} |\mathcal{A}_j(uN, k)| du = \int_{1/\log N}^{\log N} e^{-u} |{\mathcal A}_j(uN,k)| du + O\big(\frac{N}{\log N}\big), \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\sum_{n\in {\mathcal A}_j(k)} e^{-n/N} = \int^{\infty}_0 e^{-u} |\mathcal{A}_j(uN, k)| du = \int_{1/\log N}^{\log N} e^{-u} |{\mathcal A}_j(uN,k)| du + O\big(\frac{N}{\log N}\big), \end{align*}$$

where we truncated the integral above using the trivial bound

![]() $|{\mathcal A}_j(uN,k)| \leq uN$

in the range

$|{\mathcal A}_j(uN,k)| \leq uN$

in the range

![]() $u \not \in [1/\log N, \log N]$

. Now, using (5.1) for

$u \not \in [1/\log N, \log N]$

. Now, using (5.1) for

![]() $u \in [1/\log N, \log N]$

and the estimate

$u \in [1/\log N, \log N]$

and the estimate