INTRODUCTION: “OF DINNERLESS FAME”

In late August of 1913, Joseph McGrane stood before a magistrate and packed courtroom charged with beating his wife. Denying the accusation, McGrane implored those assembled to understand the difficulty of his situation: “I have reached the point where I can stand it no longer. No militant suffragette has anything on my wife. She has made the last few years of my life unbearable. Why, your Honor, I am cook, housekeeper, and man-of-all-work about our place.”Footnote 1 McGrane expressed fraternity with other husbands of suffragist wives, specifically urging reporters to provide him with the address of Lawrence Rupp. Earlier that month Lawrence made headlines from California to Montreal after publicly protesting his wife's activism. On August 7, 1913, as Maria Rupp took the podium at a public meeting on behalf of women's right to vote, Lawrence interjected. By one newspaper account, Lawrence yelled across the crowded meeting: “Maria, come home. That's where your place is, getting me my supper, and not out here on a street corner making speeches about woman's suffrage.”Footnote 2 Another newspaper reported that Lawrence incited young boys to heckle Maria with chants of “go home to your husband and kids. This man hasn't had supper in six months!”Footnote 3 Unable to calm her husband, Maria had him arrested for disorderly conduct. Public reactions ranged from amusement to alarm, with a Cincinnati newspaper reporting that both suffragists and antisuffragists condemned Maria: suffragists maintained that “no good suffragist should permit the cause to interfere with her home duties [and] Mrs. Rupp should have prepared her husband's supper before going out to speak,” while antisuffragists declared that she had stepped beyond her sphere and that “cooking is more useful than soap box oratory.”Footnote 4 While Lawrence “of dinnerless fame” spent the night in prison, newspapers throughout the country remarked on this “politico-domestic precedent” and fed a national discussion about suffragists and their relationship to their husbands, household duties, and domestic harmony.Footnote 5

More than a missed meal, the Rupp marital dispute represented genuine anxieties about the social and cultural changes posed by women who sought formal political rights during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Gender norms of this era idealized men and women as complementary but binary opposites: men had a natural, God-given duty to work in the public sphere while women had similar obligations to the private realm of home and children.Footnote 6 The “true woman” remained apart from the public realm of politics, economics, and business. Significant changes in the nineteenth century, however, expanded the public roles open to women. Americans increasingly accepted women who engaged in politics through non-electoral channels by serving on education committees, entering into dialogue about public concerns, and taking a hand in municipal affairs.Footnote 7 Many Americans believed that women possessed domestic expertise that enabled them to protect the home from the public sphere. Thus, they valued women as moral guides for their husbands and children but could not always reconcile the idea of female domesticity with formal, electoral political participation. Antisuffragists capitalized on these fears by portraying suffragists as unwomanly, unsexed, abnormal, non-mothers who would leave the home and family en masse, levying “war against the very foundation of society.”Footnote 8

Food was a key component of these gendered antisuffrage arguments. Antisuffragists argued that women involved in the campaign for the vote lacked culinary skills, failed to cook for their husbands, and did not care that their children went hungry in their absence. With these claims, antisuffragists insinuated much more than inattention to food preparation: suffragists failing to fulfill their culinary obligations showed disregard for their homes, families, and duties as women. Thus, antisuffragists condemned Maria Rupp for failing to prepare her husband's nightly meal because her disregard of his needs signaled a dangerous disruption of gender roles.

Antisuffragist criticism of Maria Rupp tapped into broader anxieties about changes in gender, but the suffragist concurrence hints at how women's rights advocates embraced gender norms to prove their cause was nonthreatening. Like their opponents, suffragists recognized that when Lawrence Rupp did not get his dinner there was much more at stake than a satisfying meal. The historian Elna Green observes that women on both sides of the suffrage debate knew they needed to appeal to hearts and minds. Both sides, consequently, “crafted rhetoric and imagery with purposefully emotional cores.” In doing so, they created “useful stereotypical images” meant to “influence popular perceptions.”Footnote 9 Just as antisuffragists appealed to popular sentiments about gender and food, so did suffragists. This article argues that suffragists challenged claims that they abandoned the kitchen by embracing the culinary arts to demonstrate that they accepted many dominant gender expectations. In responding to antisuffrage claims, suffragists used the practice and language of cookery to build a feminine persona for their movement and to demonstrate that enfranchising women would not threaten the vital institutions of home and family. By compiling cookbooks, publishing recipes, and hosting bazaars, suffragists from around the nation engaged in a public dialogue about the compatibility of politics and womanhood. By writing about food and displaying cooking skills, suffragists demonstrated their ongoing commitment to dominant gender expectations even as they demanded the right to vote.

Despite the pervasiveness of suffrage cookery rhetoric between 1880 and 1920, historians have not recognized the role it played in suffragists’ expediency tactics in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. With her 1965 seminal work, the historian Aileen Kraditor described a shift within the suffrage movement from rights-based activism to arguments based on expediency: while the early movement lobbied for the ballot in the name of justice and natural rights, suffragists in the twentieth century insisted that woman suffrage was practical and beneficial to society.Footnote 10 In contrast to more egalitarian right-based arguments, suffragists’ expediency arguments typically reinforced race and class hierarchies by arguing that only morally superior middle- and upper-class white women could effectively wield the ballot alongside white men.Footnote 11 Although “rights based” and “expediency” remain useful categories of pro-suffrage arguments, historians have overturned Kraditor's chronological shift from one tactic to another beginning in the 1890s. Scholars instead acknowledge that both arguments coexisted and that white leaders often bolstered class and race hierarchies throughout the course of the movement.Footnote 12 Although the historiography has moved away from a declension model where racist and classist expediency arguments displaced the egalitarian approach of the early suffrage movement, many scholars continue to describe gendered expediency arguments as corrupting “more pure” feminist roots.Footnote 13 One historian, for example, argues that “hard-core feminism” was “gradually displaced by social feminism,” which moved away from “a premise of equality between the sexes” to emphasize a unique female essence that would improve politics. This shift both “helped detach the vote from a larger feminist program” and contributed to the “depoliticization” of the “movement's original challenge to female subordination.”Footnote 14

This article argues against this declension narrative. I demonstrate how suffragists’ deployed cookery as one of several expediency arguments to revitalize their movement in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Suffragists’ emphasis on domesticity coincided with the merger of the National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association that resulted in the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). With this consolidation of the most prominent and national forces in the suffrage movement, NAWSA began excluding radical or unseemly elements of the movement.Footnote 15 The organization's decision to avoid divisiveness largely came from leaders who believed that the radical tactics of the past had proved ineffective and that a new course of conservative rhetoric would be more effective in educating the public.Footnote 16 Suffragists’ focus on women as “the nurturers of society” offered a means to assure a hesitant public that the franchise would help women solve social ills, a tactic that posed less of a threat to the status quo than rights-based arguments.Footnote 17 These expediency arguments—including cookery rhetoric—reinforced race, class, and gender hierarchies. Acknowledging that this strategy did not represent a break from an “egalitarian” or “more feminist” suffrage movement, however, allows this article to chart how and why suffragists embraced and manipulated dominant gender expectations through cookery rhetoric.

By considering food as a tactical element of the movement, this article forces a reinterpretation of the so-called suffrage doldrums—the years between 1885 and 1910 that historians typically describe as an era of inactivity marked by little success.Footnote 18 The suffrage movement's politicization of food culture, however, emerged in the 1880s and proliferated in the 1910s. In line with the scholarship of historian Sara Hunter Graham, this study of cookery shows that this period was actually a “suffrage renaissance” marked by active reorganization, reevaluation of tactics, and changes in political strategy.Footnote 19 Expediency arguments about food and domesticity did not represent an ideological or organizational declension; rather they indicate one way in which suffragists revitalized their movement by politicizing municipal housekeeping rhetoric and the emergent home economics movement.

Finally, examining cookery rhetoric in the woman suffrage movement means reevaluating the role of gender expectations, realizing that they did more than constrict and limit the fight for women's rights. While scholars acknowledge the existence of suffrage cookbooks and bazaars, they generally relegate these political tools to a colorful side note.Footnote 20 One historian's deeper analysis of suffrage bazaars characterizes domestic ephemera as unintentionally upholding traditional gender expectations.Footnote 21 At the same time, another scholar similarly argues that when NAWSA adopted socially acceptable tactics it “played directly into the hands of patriarchy.”Footnote 22 These scholars, among countless others, rightly observe the restrictive nature of domesticity, which reinforced not only gender but also race and class. This “kitchen culture”—encompassing everything from cooking utensils to recipes to food advertisements—has long constructed gender roles and outlined ways to perform womanhood.Footnote 23 Racial, religious, and evolutionary theories of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries added further weight to these gender prescriptions by arguing that dichotomous gender roles marked the supposed civility and superiority of the white race.Footnote 24 Food thus functioned as a marker of race and class status; euthenics, for instance, brought together women from the eugenics and home economics movements to cultivate a superior (white) race through better breeding and nutrition science.Footnote 25 While reaffirming the ability of kitchen culture to define gender boundaries, this article primarily focuses on how women used cookery rhetoric to resist gender restrictions. When suffragists discussed diet and food production they did not simply parrot the tropes of domesticity; rather, they capitalized on widespread public concerns and conversations—about health and safety, science and modernization, and the consequences of urbanization—to promote the cause of female enfranchisement. Suffragists hosted bazaars and sold cookbooks as purposeful political tactics that directly responded to charges of masculinity and unwomanly behavior by softening the image of the movement. This article thus calls for historians to reevaluate the myriad ways that suffragists co-opted the dominant discourse on womanhood. Far from corrupting the ideology and objectives of the suffrage movement, cookery proved a politically savvy tactic to combat the perennial image of suffragists as unwomanly women and gain the movement greater public support.

HOME ECONOMICS AND A BETTER TYPE OF COOKING

The late nineteenth-century United States experienced profound changes in the production, consumption, and politics of food as the national food system underwent industrial modernization.Footnote 26 With the rise of corporate agriculture and food processing, Americans increasingly ate grains grown hundreds of miles from where they lived, cooked meats transported in refrigerated railcars, and purchased packaged foods at the local grocer.Footnote 27 The technological changes that assisted the rise of commercial food production also appeared in private homes: iron stoves and ranges made it possible for middle-class Americans to create more elaborate dishes, feeding a demand for cookbooks and domestic manuals.Footnote 28 Although poor and rural Americans did not have immediate access to these technologies, new kitchen tools and domestic conveniences spread quickly in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.Footnote 29 As early as the 1880s, urban reformers realized that this industrialization generated significant sanitary, dietary, and food safety problems, and they sought to improve the nation by changing the eating habits of all Americans.Footnote 30

In the late nineteenth century, the nascent home economics movement developed alongside broader middle-class and progressive reform efforts focused on improving food safety and eating habits. That century also witnessed a virtual cookbook revolution as American women turned away from European culinary instructions to pen their own cookbooks and domestic manuals on food preparation, frugality, temperance, and practical home management. Emerging from this wave of female culinary writers, Catharine Beecher emphasized the importance of studying the role of women in the home and insisted that women apply business principles to domestic labor.Footnote 31 This cooking culture combined with the falling price of exotic ingredients, the availability of processed foods, and the sale of new kitchen gadgets to make it easier for middle-class women to imitate the dining habits of the upper class (although they often did so with far less domestic help).Footnote 32 This cooking revolution prepared an educated middle class, “more awed by modern scientific wisdom,” to accept the purported “science and professionalism” of food reformers and home economists by the turn of the twentieth century.Footnote 33

Even before the first organized meeting of home economists in 1899, suffragists capitalized on this particular moment when cooking and food instruction became increasingly important to the middle class by publicly espousing the value and importance of scientific cookery. Reviews of cookbooks in major suffrage newspapers, for example, demonstrated an interest in cookery and a commitment to healthful food, nutrition, and sanitation.Footnote 34 Articles on household tips ranged from childcare to laundry instructions, sanitizing fruit cans, and how to reduce waste.Footnote 35 Many of these articles emphasized the weighting and measuring of ingredients, included timetables for managing the kitchen, and offered “simple, sensible” recipes with “practical and minute instructions.”Footnote 36 This suffrage domestic advice aligned with early home economists who hoped to adjust American attitudes toward food, making their behaviors in the kitchen more rational, scientific, and healthy.Footnote 37

Early suffrage cookbooks drew on ideals of scientific home management, making subtle connections between their cause and the budding home economics movement (which, again, did not formally organize until 1899). The Woman Suffrage Cookbook (1886 and 1890), for example, often called for specific kitchen tools, precise temperatures, exact cooking methods, and careful measurements.Footnote 38 Suffragists’ scientific and rational approach to food extended to many of the recipes, which instructed readers to control and manage food, creating casseroles with neat layers or forming ingredients into tidy spheres.Footnote 39 Several recipes, provided by suffragists active in the home economics movement, such as May Wright Sewall, promised that the resulting dish would provide an odor appealing enough to trigger appetite—a physiological concern for home economists.Footnote 40 Mary J. Safford also submitted Frances Willard's “Protest Against Pepper” to the cookbook (both women supported home economics). Warning against pepper as the “abomination to the sense of every normal stomach,” Willard stood for “stomachic rights,” “plain living and high thinking.”Footnote 41 First published in the 1880s, suffrage cookbooks, recipes, and domestic advice articles grew out of connections between women's rights advocates, food reformers, and the emergent home economics movement; these connections strengthened by the 1910s as suffrage cookbooks and recipes became an integral part of the movement and explicitly drew from an organized and established home economics movement.

The Progressive Era, with its emphasis on scientific explanations and social reform, created the space for a national movement that would transform American eating habits.Footnote 42 This domestic reform movement—varyingly known as scientific housekeeping, home science, progressive housekeeping, scientific cooking, and domestic science—ultimately called itself home economics.Footnote 43 Intent on professionalizing domestic labor, the home economics movement sought to bring science, rationality, and modernity to the work of running a household.Footnote 44 Home economists studied nutrition, crafted balanced recipes, observed the physical and chemical processes of eating, sought the most rational ways to organize the kitchen, and pushed for a nation of women trained to run efficient households. Making the home a “more businesslike place,” they argued, would improve the home, elevate the work of women, and strengthen the nation.Footnote 45 Home economics “required a significant cultural shift” as physical labor within the home veered away from associations with servitude, gaining prestige that called for the modern housewife to embrace domestic labor as the embodiment of her intelligence and familial love.Footnote 46 Far removed from the political radicalism of early food reform and steeped in the scientific rationality of the Progressive Era, leaders within universities, public schools, the food industry, and women's clubs began to propagate home economics.Footnote 47 By the 1910s, middle-class Americans were well versed in the ideals, rationale, and practices of the movement, by then a core component of many cookbooks.Footnote 48 And like other progressive reformers, many suffragists supported home economics.Footnote 49 Suffragists, however, did not just join the home economics movement—they capitalized on its popularity to promote votes for women.

Building on awareness of home economics and drastic changes to American foodways, antisuffragists at the turn of the twentieth century argued that suffragists encouraged women to leave their kitchens and abandon the American home when the family and nation most needed them. Although diverse groups and individuals opposed the suffrage movement for more than seventy years, antisuffrage arguments often implicitly and explicitly tapped into conventional gender ideologies: in doing so they came back to foundational ideas about womanhood, the natural role of women, and the potential consequences of violating these norms.Footnote 50 Antisuffragists thus frequently described suffragists as working against the best interests of the home and family. One antisuffragist in 1905, for example, argued: “The word ‘housewife,’ is a mockery to those suffragists [who] want to be out all the time.”Footnote 51 Another author urged suffragists to stop “influencing your weaker sister to neglect her housework and get out and clamor for suffrage.” Instead, suffragists needed to realize that “the home is the real thing in this world” and women must “rule over it like a queen [for] its duties are endless.”Footnote 52 Suffragists abandoned their home duties in favor of politics, obviously not caring about the food challenges that faced the modern home.

Suffragists drew from the popularity of the home economics movement in responding to antisuffragists, explicitly linking female enfranchisement to improved, scientific cookery. By printing recipes for “suffrage savories” or “spaghetti a la suffragette” suffragists linked the ballot with cooking and declared, “We are all hungry for something new in the way of eatables, as well as for votes.”Footnote 53 Suffragists brought together the ideal foods and the latest cooking methods and promised to “secure the maximum nourishment with the minimum expense.”Footnote 54 Newspapers noticed, and sometimes applauded, suffragists’ use of home economics principles. In direct contrast to antisuffrage predictions, the Friend's Intelligencer argued in 1909 that suffrage was more likely to improve than destroy the home: “[Female suffrage] will, in all probability, change the home very materially. It will make it better, something more consonant with the present stage of the world's development. It will bring the home up to date, make it a twentieth-century home.”Footnote 55 By the 1910s, suffragists worked to demonstrate that as educated, thoughtful, and conscientious citizens, women's rights advocates and enfranchised women could improve modern home life. New York suffragists blended scientific cookery and enfranchisement in a 1916 cookbook that argued, “‘Preparedness in the Home’ and ‘Vote for Women’ stand together.” Their ideal home was simplified, efficient, and based on practical equipment. By designing their cookbook around electrical appliances—coffee percolators, oblong grills, electric freezers, portable ovens, waffle irons, and chafing dishes—these middle-class suffragists embraced home economics and modern technology so that “woman's usefulness to the community and the home [will] be widened.” They also explicitly connected enfranchisement to scientific cooking, arguing that the vote would empower women to use their knowledge of the home to improve the public and private realms: “With learning, wit, and strength and heat/ The hour is not remote/ When women from their drudgery freed/ Will all the nation wisely feed/ And scour with the vote.”Footnote 56

Although suffragists worked in the home economics movement and drew from its approach to rational home management, their discussion of scientific cookery differed because of their focus on politics, gender inequality, and voting rights. As suffrage cookery texts first emerged, the two movements subtly diverged in how they discussed food. Emblematic of this is how suffragists and home economists described drudgery. Home economists argued that the constant exhaustive labor of women that pitted them against malnutrition, poison, disease, and waste turned them into drudges who perpetually fought the miseries of the home.Footnote 57 Home economists gladly embraced the private sphere as the location of true womanhood, but they argued that women needed scientific cookery to “both lift and clarify the status of the woman in charge of the kitchen.”Footnote 58 Battling drudgery would thus improve the quality of women's work, forcing society to recognize the importance of her labor and elevate her status.Footnote 59 Suffragists similarly acknowledged that the joys of running a household and caring for a family could become irksome and devolve into drudgery.Footnote 60 The first four volumes of The History of Woman Suffrage (published between 1881 and 1902), for example, frequently referenced “domestic drudgery” and the relegation of women to the role of “household drudge.”Footnote 61 Unlike home economists, The History linked domestic drudgery to sex inequality. Quoted in the first volume, Ann Preston argued: “To be an ornament in the parlor or a mere drudge in the kitchen, to live as an appendage to any human being, does not fill up nor satisfy the capacities of a soul awakened to a sense of its true wants, and the far-reaching and mighty interests which cluster around its existence.”Footnote 62 Although many likely believed in the merits of scientific cookery as earnestly as any home economist, suffragists identified the home as a site of sex and gender oppression. Whereas home economists generally avoided discussing women's rights or politics, suffragists linked scientific cookery and food with the public role of women and formal political rights.Footnote 63 Like historians who dismiss suffragists’ gendered expediency arguments as harmful to the movement, some scholars criticize the home economics movement for choosing “domesticity as a way of getting out of the house.”Footnote 64 As this article illustrates, however, women wielded cookery, domesticity, and food as powerful tools against gendered social and political restrictions.

THE POLITICAL UTILITY OF FOOD

In the twentieth century, suffragists capitalized on changing understandings and valuations of domesticity that increasingly saw work within the home (from cooking to childcare) as a significant sphere of daily life.Footnote 65 Like clubwomen around the nation, suffragists identified a range of social problems—from poor housing, to child labor, and inadequate education—that women could help men remedy.Footnote 66 Through the rhetoric of municipal housekeeping, these women emphasized the similarities between the home and city, arguing that women's unique skills made them ideally suited to lead civic betterment projects.Footnote 67 In particular, municipal housekeeping advocates pointed to air quality, food purity, and city sanitation as domestic concerns. Much like the home economics movement, municipal housekeeping germinated in shifting understandings about the meaning and value of women's domestic labor. And municipal housekeeping, in part, became incredibly popular with women's clubs because it was a nonpolitical term that justified women's entry into public spaces and encouraged women to undertake a variety of reform work in their communities.Footnote 68 Municipal housekeeping, however, took on new political meanings in the context of the suffrage movement. As they did with home economics, suffragists politicized municipal housekeeping. By embracing municipal housekeeping—and capitalizing on its emphasis on femininity and domesticity—suffragists justified the expansion of the franchise in language consonant with popular ideas about gender. Viewed in this way, scholars will struggle to dismiss the political utility of domesticity and to characterize the years between 1885 and 1910 as a suffrage doldrums.

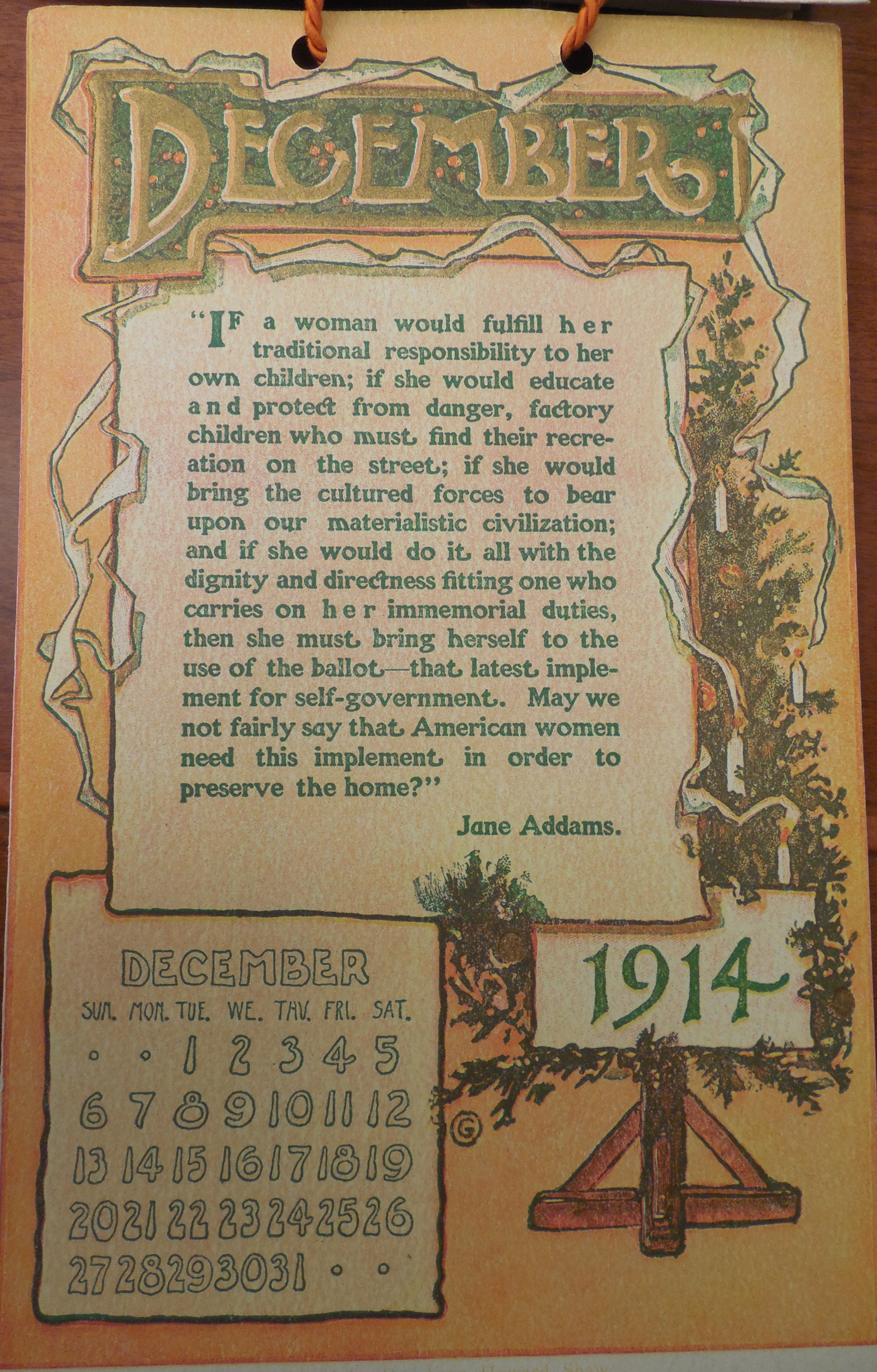

By the early twentieth century, suffragists frequently and consistently argued that private and public concerns were both deeply intertwined and highly political. Writing in the suffrage newspaper The Yellow Ribbon in 1907, for example, recent NAWSA president Carrie Chapman Catt observed: “It is sometimes thought that politics deals with matters difficult to understand, and quite apart from affairs of the home.” Catt assured women, however, that politics permeated their homes and domestic concerns—from the food on their family table to the vaccinations mandated for their children. She argued that the only solution was to “seat the ‘Queen of the Home’ upon the throne of government beside the ‘King of Business,’ and let them rule together.”Footnote 69 While reinforcing women's responsibility for clean homes, safe food, and healthy children, suffrage pamphlets argued that many factors influencing the physical condition of the home remained beyond a woman's control and suffragists wanted the vote precisely because of their dedication to the private sphere: one suffragist insisted, “I am a housekeeper. Even the antis will allow that that is a perfectly proper thing for me to be” (see Figure 1).Footnote 70 Drawing on the rhetoric of municipal housekeeping, suffragists insisted that the only way for society to improve conditions that bridged public and private life was to allow women to use their unique talents: “Women are, by nature and training, housekeepers. Let them have a hand in the city's housekeeping, even if they introduce an occasional house-cleaning.”Footnote 71

Figure 1. Anna Howard Shaw, “Votes for Women Ryte-Me Postcard Calendar: Containing Twelve Reasons Why Women Should Have the Right to Vote and Twelve Ryte-Me Post Cards” (Stewart Publishing Company, 1914), Susan B. Anthony Ephemera Collection, box 11, Huntington Library. This calendar reproduced suffrage articles and pamphlets that drew explicit connections between food, the home, and female enfranchisement.

Such municipal housekeeping arguments drew significant numbers of women and men into the suffrage movement and were a key factor in state victories. Cities in Illinois and California, for instance, experienced a surge in women's municipal activism before the development of a strong suffrage movement. These women often worked together with men for the sake of urban reform and development, seeing their work as a civil rather than political effort. Through this activism many women came to see themselves as political actors and the ballot as a tool for civic betterment; and these broad movements for good government evolved into suffrage coalitions that crossed gender, racial, ethnic, and class lines.Footnote 72 Historians argue that suffragists’ emphasis on the ballot as a practical tool for women to extend their domestic skills and morality to the public sphere brought the suffrage movement both the endorsement of many clubwomen and much wider public support.Footnote 73 In fact, some scholars list municipal housekeeping arguments as a crucial factor in states granting women the right to vote years or even decades before the federal amendment.Footnote 74 More so than in any other region, western suffragists actively changed their arguments to emphasize that enfranchised women would remedy dangerous social conditions (from drinking and gambling to prostitution). And these expediency arguments helped them win the vote because they resonated with widespread gender norms.Footnote 75 Suffragists were cognizant of the broad appeal of these arguments—which fostered alliances with municipal reformers and clubwomen and spurred success in the West—and included them in their regional and national arsenal of political tactics.

Although suffragists employed many municipal housekeeping arguments, historians generally overlook their acuity in capitalizing on widespread fears about industrial food production and food safety. For many Americans, food fundamentally changed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as big businesses increasingly transported, transformed, and marketed processed foods.Footnote 76 Technological developments did not just allow companies to package food, but also to chemically preserve it, mask signs of decomposition, alter colors and flavors, and add fillers; profit-driven, “unscrupulous food producers” used these adulterations as manufacturing shortcuts.Footnote 77 Food safety then entered the national spotlight at the turn of the twentieth century through the work of journalists, food reformers, home economists, and clubwomen.Footnote 78 Whereas home economists avoided explicitly connecting impure food and politics, suffragists utilized widespread fears about unreliable food manufacturing to argue for their cause.Footnote 79 For instance, the title page of the 1916 Choice Recipes Compiled for the Busy Housewife, sponsored by the Clinton Political Equality Club, quoted well-known food chemist Dr. Harvey Wiley on female enfranchisement as the solution to impure food: “If the members of the women's clubs of the nation could vote, it would not be to [sic] difficult to secure pure food and drug legislation.”Footnote 80 Throughout the first decades of the twentieth century, suffragists highlighted the connections between their movement and pure food; suffrage bazaars included “pure food talks” and “pure food exhibits” that encouraged onlookers to witness that suffragist “home-makers” wanted to take their rightful place as “civic housekeepers.”Footnote 81

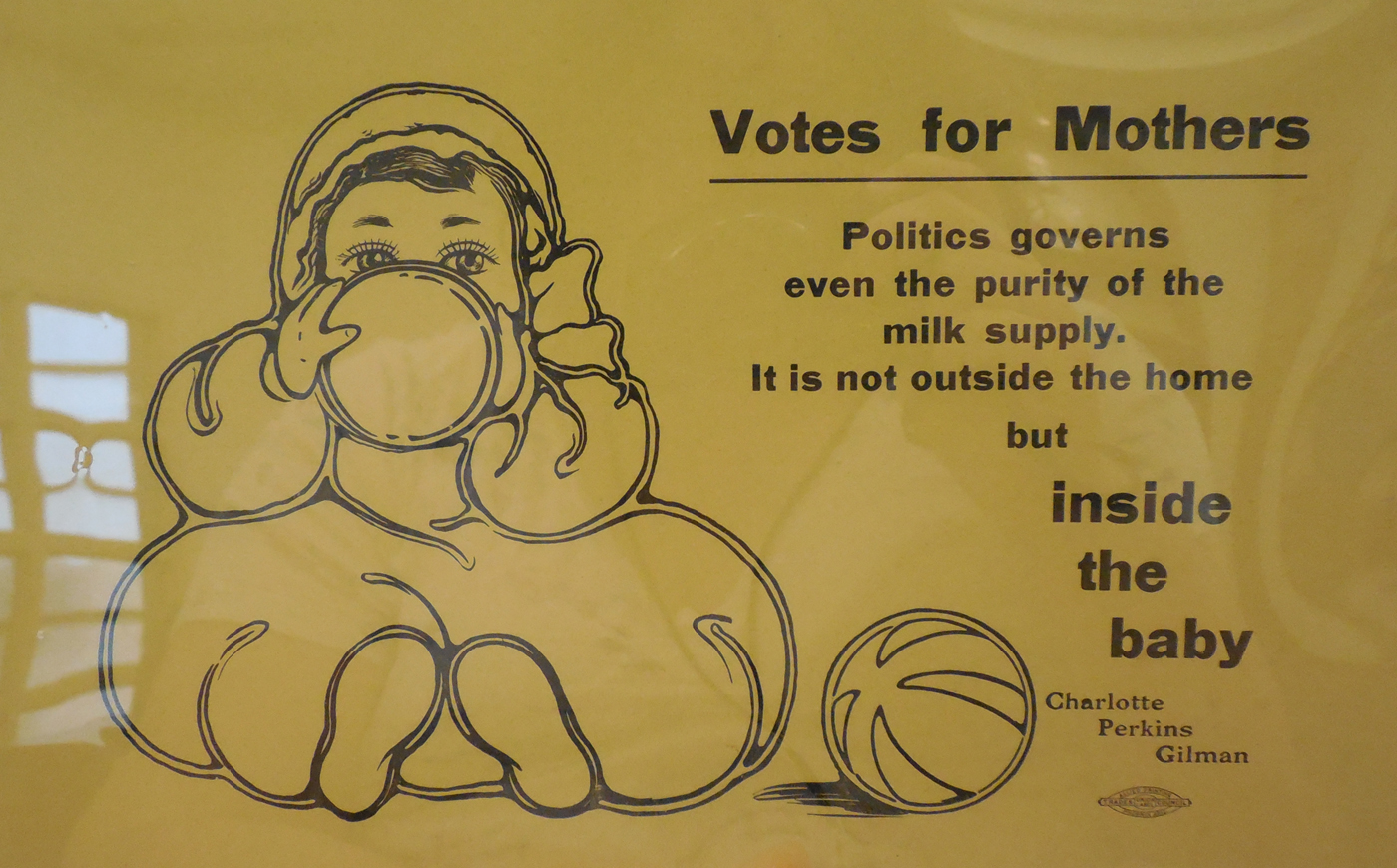

The epitome of the suffrage politicization of food safety came with the campaign for pure milk in the 1910s. An icon within this campaign, the illustration of a chubby, doe-eyed baby graced suffrage postcards in 1912. Below a proclamation of “Votes for Mothers,” a quote from Charlotte Perkins Gillman read: “Politics governs even the purity of the milk supply. It is not outside the home but inside the baby” (see Figure 2).Footnote 82 In a private letter, California suffragist Alice Park explained the success of this slogan and encouraged other suffragists to reproduce it: “This picture and quotation were used on a poster in our campaign. I make up the plan, and my daughter Harriet drew the original baby. But I always wanted a window card—and wanted to place it in barber shops—because men—a procession of men go there—and have to wait—and can talk.”Footnote 83 Emphasizing their inability to directly influence pure food legislation, suffragists argued women could only safeguard vulnerable children with the vote.Footnote 84 Mrs. Donald R. Hooker, for example, urged readers to consider “the infant in arms”: “Men and not women legislate as to the quality of milk the babies may drink, and the result is that in Baltimore every summer between 700 and 800 infants die as a result of impure milk.” If society allowed women to do their “natural business,” she argued, then they would oversee the quality of the milk supply with the support of the ballot.Footnote 85 Newspapers were receptive to these expediency arguments that did not focus on equal rights rhetoric. A 1913 article complimented the suffrage pure milk campaign, calling it a “mildly argumentative device” with a “pacific tenor of appeal.” The impressed author applauded suffrage parade banners addressing babies and pure milk because they resulted in a “friendly reception” with “little jeering” or “disorder.”Footnote 86

Figure 2. Votes for Mothers (October 1912), Susan B. Anthony Ephemera Collection, box 13, Huntington Library.

Along with grounding these arguments in dominant gender expectations surrounding femininity, domesticity, and motherhood, suffragists intentionally capitalized on popular discussions about nutrition and food safety to promote their movement. In a 1907 article in the suffrage newspaper The Yellow Ribbon, suffragist Molly Warren outlined all of the cities and states around the nation considering laws related to the milk supply. Warren maintained that the political debates about milk safety effectively proved the need for women to carry their housekeeping skills “into public dealings, making officials feel that she is watching how they handle food supplies.” The ballot was absolutely necessary, she argued, because “moral suasion, accompanied by a vote in the husband's name only, avails little.”Footnote 87 Whereas home economists and municipal housekeepers avoided contentious politics, suffragists directly stated that women needed more than female moral influence. Women must have the vote. Suffragists reinforced this argument by highlighting how enfranchised women in the western states found their “united influence” for measures related to pure food and sanitation “more powerful because it has votes behind it.”Footnote 88 Although disenfranchised women throughout the nation worked to improve the milk supply, they did so “under far greater difficulties.”Footnote 89

REPAIRING THE SUFFRAGE IMAGE

At the turn of the twentieth century, suffragists confronted a feverish public debate about whether the ballot would not only change women in fundamental and irreversible ways, but also whether voting would destabilize the home. An editorial in The Washington Herald in 1910 conceded the necessity of women's enfranchisement if it came down to “justice between man and woman.” Admitting that the movement “may be brave and idealistic,” the authors nonetheless concluded that suffrage and womanhood were incompatible. In fact, women could best “make the world a happier and sweeter place” by focusing on homemaking, on “being a companion to her husband, a tender and loving mother to her children, a good housewife.”Footnote 90 And in a 1908 survey of “leading men,” Representative Cordell Hull of Tennessee declared suffrage a “wicked imposition” because the “destiny of this Republic” depends on “typical American homes, presided over by womanly women.”Footnote 91 For opponents, suffragists threatened this model of the home and nation when they demanded electoral rights because extending the ballot challenged the social hierarchy of the sexes in which men politically represented women. Thus many warned that if women no longer depended on men for political representation, then marriage, children, and the home would be jeopardized as well. Although criticisms of the suffrage movement began in the previous century, they increased in the twentieth century with what one historian calls a “multimedia barrage of criticism unknown to their predecessors.”Footnote 92 Suffragists capitalized on the popularity of scientific cooking, home economics, and municipal housekeeping to repair their image; their cookbooks and recipes demonstrated their personal and sincere commitment to domesticity, nutritious and safe foods, and an inviting home life.

Suffrage cookbooks served multiple purposes—they raised funds to cover the costs of campaigns, advertised the movement, and refuted antisuffrage claims that women's rights advocates abandoned their kitchens, homes, and families. Local suffrage organizations often printed and sold cookbooks to supplement the cost of running state and national campaigns; some of these fundraising efforts were unsuccessful, despite suffragists insisting that the success of their movement depended upon selling memorabilia.Footnote 93 Suffragists also created cookbooks to capitalize on skills they already possessed. A pamphlet on fundraising from the National Woman Suffrage Publishing Company, for instance, urged local suffrage organizations to consider the skills of their active members and turn their “specialty into money” by baking, pickling, and sewing.Footnote 94 Suffrage cookbooks, in particular, arose from a wave of community cookbooks that women's organizations compiled in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as one of the most profitable forms of female charity work.Footnote 95 Suffrage cookbooks followed patterns seen in community cookbooks as they expressed the dual purpose of supporting their cause and sharing delicious recipes, attested to the reliability of their instructions, and incorporated household tips. Suffrage cookbooks also followed two of the key plots that English scholar Annie Bower found in community cookbooks: with the integration plot, suffragists emphasized “social acceptance and achievement,” telling a “story of the authors achieving assimilation through their acceptance of the larger society's conventions and standards”; simultaneously, suffragists used the differentiation plot wherein “the communal authors define themselves in some way different from other women,” but they “never position themselves as rejected by the larger society.”Footnote 96 With these integration and differentiation plots, women both reinscribed and resisted domestic gender ideology through the gendered medium of cookbooks.Footnote 97 Thus, although community cookbooks celebrated the private sphere, they could also “rebuke a social order that devalues women's work.”Footnote 98 Furthermore, as folklore scholar Janet Theophano argues, cookbooks often disguised “social disruption” with “unassuming rhetorical strategies.”Footnote 99 Suffragists therefore created cookbooks to share recipes, raise money, and advance their political arguments; readers who followed the recipes could personally experience the success of suffrage cookery, the truth of suffragists’ domesticity, and, perhaps, a conversion to the cause. After all, as a Florida newspaper exclaimed in 1917, those who “eat one or more of the dishes cooked according to these directions” will remember “good cooks not only want, but need and deserve good votes.”Footnote 100 And by attacking the “age-old channel of the stomach,” a California paper declared, these cookbooks proved to men that “a woman need not lose interest in cookery because she is a suffragist.”Footnote 101 Suffrage cookbooks also strove to reach new audiences by adopting a literary form familiar to many women. The Woman's Journal praised suffrage cookery texts for placing suffrage propaganda in the hands of “those women who think they have ‘all the rights they want,’” the women who “will read a cook-book when she will not read anything else.”Footnote 102

Cookbooks offered suffragists a feminine and nonthreatening way to promote their beliefs. In evaluating the 1912 election in Kansas, Ida Husted Harper, a prolific suffrage writer, promised the New York Times that the “clean and honest” suffrage campaign used “methods dignified and womanly, [with] no ‘militancy,’ and no lawbreaking.” They used the right methods, Harper argued, by “talking things over” with “their men,” canvassing house to house, hosting fairs and suppers, and publishing a cookbook.Footnote 103 The foreword of the New York pamphlet on Votes for Preparedness in the Home similarly promised, in the form of a poem, that “we don't inveigh with noisy din/ Nor loudly gerrymander;/ We only say, while cooking goose—/ ‘This is the proper gander.’”Footnote 104 Some politicians and newspapers recognized suffrage cookery texts as a form of political maneuvering: opponents labeled the Washington cookbook a “political trick.”Footnote 105 Emma Smith DeVoe, a leading activist in the Northwest, argued that these men misjudged suffragists’ motives: “It's a very good cook book. We made it all ourselves. It embodies the best efforts of some of the best cooks in the State of Washington.”Footnote 106

As earnestly as suffragists claimed that cookbooks embodied their dedication to the home and their sincere interest in cookery, they also designed cookbooks as subtle political texts. DeVoe, for instance, avoided any radical techniques and embraced femininity because she believed it the best way to win allies in the West. DeVoe described the Washington cookbook as nonpolitical; however, she also acknowledged it was a “vindication of the slur” that suffragists lacked domestic traits.Footnote 107 Although seemingly contradictory, this approach allowed activists to advertise their cause and counter negative stereotypes while avoiding the taint of radicalism. While some newspapers criticized this “trickery,” others praised DeVoe as “motherly looking” and “nonmilitant” and complimented the cookbook as evidence of the “subtileness [sic] of the campaign” that appealed to man's stomach.Footnote 108 As a refutation of “that favorite argument of the ‘antis’ that suffrage is likely to masculinize women,” the cookbook promised to revive the image of activists as domestic loving creatures by providing “recipes equally good for attracting the mind and the appetite.”Footnote 109 As one creative tool suffragists used to raise money and promote their movement, cookbooks created positive stereotypes through womanly, “nonpolitical,” nonradical means.

Newspapers eagerly and favorably reported on the publication of suffrage cookbooks, and they even recognized their ability to dispel gendered antisuffrage claims. In an article reprinted in the Woman's Journal, the staff of the Record complimented those “wise sisters” for giving the suffrage cause a “mighty impetus” by waging a “skilful [sic] assault” on the “unyielding will of legislators or ordinary voters” through a “conquest by cook-book.” Weeks away from its final publication, these writers expressed confidence that the suffrage cookbook could “turn more than one vote.” With humor and apparent sincerity, the Record imagined politicians converted with a celery salad, lawmakers seized with a “persuasive dish,” and antisuffragists overtaken by “vote-compelling refreshments.”Footnote 110 This suffrage cooking manual, The Woman Suffrage Cook Book, compiled in Boston by Hattie A. Burr, first published in 1886 and reprinted in 1890, aimed to fulfill an “important mission.” In addition to serving as a “practical, reliable authority on cookery, housekeeping, and care of the sick,” Burr intended the text be “an advocate for the elevation and enfranchisement of woman.”Footnote 111 The Record, now with cookbook in hand, declared it a “potent missionary” sure to “convict and convert.”Footnote 112

Newspapers praised The Woman Suffrage Cook Book, in part, because it included the names and recipes of actual suffragists from around the nation. The Record testified that “alarmists of both sexes” declared suffrage and domesticity utterly incompatible. The cookbook, however, would be “a confession book, a proof that, even if they wish to vote, the suffragists cherish a feminine interest in culinary matters.”Footnote 113 With over one hundred and fifty names, the list of contributors attested to a nationwide base of suffrage supporters capable of crafting a meal: many lived within the Northeast but a significant number sent savory instructions from as far away as Iowa, Nebraska, Oregon, Illinois, Kansas, Texas, Montana, and London. Burr removed the abstraction of suffragists as cooks by attributing each recipe to its creator: readers could now associate Alice Stone Blackwell with scalloped onions, Matilda Josyln Gage with baked tomatoes, Clara Berwick Colby with grape jelly, and Lucy Stone with homemade yeast.Footnote 114

Suffrage cookbook editors around the country linked specific activists to domesticity by attributing recipes to individual women, thereby garnering favorable press coverage. Although it took on different forms, suffragists frequently identified contributors in suffrage cookery texts: both the full-length work from Detroit and a New York pamphlet provided attribution; the cookbooks from the Clinton Political Equality Club and Wimodaughsis linked each recipe with its contributor; a small book created for a 1915 NAWSA convention contained recipes from female voters in California who continued to cook; and a baking pamphlet from New York titled each recipe after a famous activist (from “Aunt Susan Marble Cake” to “Lucy Stone Boston Brown Bread”).Footnote 115 Author attribution in suffrage cookbooks mirrored community cookbooks; an editor penned an introduction on behalf of the organization, outlined the goals of the cookbook, and then attributed individual recipes to the specific members of the community who supplied them. So while the editor introduced the text and its purpose, by attributing the recipes to their creators, she reminded the “reader that individual women have used, adjusted, and served these dishes.”Footnote 116 Similar to Burr, The Suffrage Cookbook, edited by L. O. Kleber, included a list of national contributors from Alabama to Wyoming, California, Virginia, Kentucky, and Arizona.Footnote 117 Endorsed by the Woman's Journal as “in itself an argument for the cause,” the cookbook attracted praise because it highlighted prominent contributors. In fact, the Woman's Journal argued that Kleber's cookbook “ought to silence forever the slander that women who want to vote do not know how to cook.”Footnote 118 The popular press also took notice of specific dishes signed by their suffragist creators. The New York Tribune, for instance, observed, “There is scarcely a suffragist of note in the country who isn't represented in this pretty blue bound book.” The article pointed to the “fine breads” that were the “proudest achievement” of Medill McCormick and the “pain d'oeufs” that Carrie Chapman Catt made, “her friends say, with all the skill with which she delivers a suffrage speech.”Footnote 119 The Milwaukee Leader also published a collection of suffrage recipes in 1912 under the headline: “Will Suffragists Neglect Home? Try These Recipes, Then Judge.”Footnote 120 Suffragists meant these recipes to demonstrate their commitment to domesticity and love for and skill with a particular dish. Any reader who doubted that “womanly” suffragists possessed “feminine virtues” simply needed to turn to their recipes and “see your error.”Footnote 121

Suffrage cookbooks also used the formula of a recipe to introduce humor, address political issues, and critique opponents. “Anti's Favorite Hash,” in The Suffrage Cookbook (1915), for example, called for “1 lb. truth thoroughly mangled/ 1 generous handful of injustice/ (Sprinkle over everything in the pan)/ 1 tumbler acetic acid (well shaken).” The recipe suggested, “a little vitriol will add a delightful tang and a string of nonsense should be dropped in at the last as if by accident.”Footnote 122 Along with criticizing antisuffragists, the cookbook provided a recipe on how to convert the hesitant by baking the perfect “Pie for a Suffragist's Doubting Husband.” The primary ingredients included civic and social issues women could improve with the vote: “1 qt. human kindness/ 8 reasons:/ War/ White Slavery/ Child Labor/ 8,000,000 Working Women/ Bad Roads/ Poisonous Water/ Impure Food.” Most importantly, “mix the crust with tact and velvet gloves, using no sarcasm, especially with the upper crust [which must be] handled with extreme care for they sour quickly if manipulated roughly.”Footnote 123 Like countless suffrage pamphlets, books, articles, and speeches, these recipes addressed issues central to the debate over woman's suffrage but did so in a fanciful and humorous way. Suffragists’ recipes imbedded deeply political issues in a form and context that used domesticity and cookery as metaphors for political engagement. Thus, even if equality seemed a “queer subject for a cook-book,” activists hybridized cookery instructions with political tracts to appeal to a wider audience.Footnote 124

Suffragists most directly and literally displayed their commitment to food, domestic science, and the home through practical demonstrations that fed their audiences. From the early nineteenth through the turn of the twentieth centuries, women's organizations around the country hosted fundraising fairs to benefit a variety of causes. These women's fairs simultaneously reinforced and undercut expectations of domesticity by combining the sale of food and home goods with the business, marketing, publicity, and bookkeeping skills necessary for running such large events.Footnote 125 The political purpose of suffrage bazaars, women's studies scholar Beverly Gordon argues, “was certainly evident” as banners and booths advertised that the fairs raised funds for suffrage organizations.Footnote 126 Journalists noted this décor, focusing on how “tastefully decorated” bazaars offered consumers a variety of “fancy articles.”Footnote 127 This type of positive press coverage played into suffrage tactics by promoting the domesticity and visibility of the movement without stressing divisive elements of the suffrage debate. A NAWSA handbook on “Organizing to Win,” published in the 1910s, emphasized the need for such events to appeal to those skeptical of the movement: “All our technical, political and legislative work will profit us little unless we are at the same time preparing the minds of the people for this great reform.” Workers and committees must “devise a thousand ways of appealing locally and generally to the heart and mind of the unconvinced, and of getting the message of equal suffrage to those who would never come to us in a regular suffrage meeting.” Along with booths at pure food and domestic science exhibits, the instructional pamphlet recommended setting up suffrage lunch wagons (see Figure 3). Such “unusual demonstrations,” as long as they were “dignified, gracious, tactful and earnest,” would bring the “truth of democracy” to new audiences.Footnote 128 With this advice listed under the “propaganda” section of the handbook, suffragists were well aware that food was a channel for converting Americans to their cause.

Figure 3. “Suffragettes Furnish Homemade Food to Hungry Wall Street Brokers,” San Jose Mercury Herald, 1915, Susan B. Anthony Ephemera Collection, clippings, volume 16, Huntington Library. Suffragists in 1915 made headlines for furnishing “Homemade Food to Hungry Wall Street Brokers.” Operating out of a restaurant and multiple lunch wagons, “suffrage sundaes, cooling beverages made principally of peaches, were handed right and left” and “the suffrage dainties vanished almost immediately.” The food “caused such a stir among the brokers that Wall street was alive from 11 o'clock till 5 with animated capitalists.” Men not only followed their stomachs to the lunch wagons, they also crowded the tables and spilled into the street listening to suffrage speakers.

Thus, in venues throughout the country, suffragists delivered “suffrage food for minds that need coaxing” at bake sales, food markets, and Saturday fairs.Footnote 129 Newspapers described suffrage bake sales and food carts, laden with cakes and gingerbread “daintily iced and decorated,” as evidence of “what good housewives they are.”Footnote 130 When breads, doughnuts, pies, and cakes sold out within an hour, the Oneonta Star reported, “the suffragists can cook.”Footnote 131 By successfully hosting dinners, Minnesota suffrage associations bore “witness to the fact that no cooking can excel suffrage cooking.”Footnote 132 While the Indianapolis News predicted, “Husbands will soon be admonishing their wives to make bread like the suffragists make.”Footnote 133 Activists in Atlanta, Georgia, impressed local diners when they opened a suffrage café to host a Shriner convention. For the café they promised “suffrage-made soup and suffrage-made salads, sandwiches, ice cream and cakes,” “dainty morsels and substantial meals that will rival even the meals that ‘mother used to make.’” By dividing up the menu and competing to create better dishes, the women of the Atlanta Equal Suffrage Association refuted “the argument of the antis that women who seek the ballot are remiss as housekeepers and as cooks.”Footnote 134 Suffragists emphasized dainty dishes, suffrage savories, and mothers cooking and intentionally played into gender expectations that said women possessed an inherent interest and skill in crafting comforting meals. Suffragists’ embrace of domesticity, however, was not accidental or ruinous to their cause. By entering public spaces with practical demonstrations of their cooking in hand, suffragists proved their compliance with gender expectations and, at the same time, insisted on their right to the franchise.

CONCLUSION: “THIS WOMAN CAN COOK”

In November 1912, The Woman's Journal printed a “pretty story” from Michigan that had “the advantage of being true.” The president of the local Equal Suffrage Association unexpectedly took charge of the woman suffrage booth at the local fair. Although unprepared for this responsibility, she stood “equal to the emergency, she baked her bread, took all the children with her, decorated the booth, looked after the children, entered her bread as ‘Suffrage Bread,’ and took first prize for it.” As the perfect example of the ideal suffragist, The Woman's Journal announced, “This Woman Can Cook, Tend Children and Work for [the] Ballot, All at Once.”Footnote 135 More than a bakery submission at a local fair, this anecdote represents a larger dialogue about the compatibility of women, political rights, and domesticity.

Large-scale social and cultural changes in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries drove the American public into a debate about the role of the sexes: as women increasingly entered colleges and the professions, the woman suffrage movement further propelled arguments about the capacities of women. Antisuffragists capitalized on anxieties about the role of women by claiming that masculine, unsexed suffragists wished to abandon the home and family. Scholars note that with such claims “anti-suffrage women articulated cultural values that were perfectly in keeping with this nation's traditions.” By claiming the importance of the home and denouncing women who stepped beyond the private realm, “antis put into words what society had believed for a long time and had practiced for generations.”Footnote 136 The dichotomy between suffragist and antisuffragist becomes less clear, in this regard, when scrutinizing how female suffragists responded to gendered charges. In adopting cookery rhetoric between the 1880s and the 1910s, suffragists began to speak the same cultural language as antisuffragists: they connected women with domesticity and socially acceptable forms of womanhood.

Over four decades, suffragists utilized food in a number of ways, capitalizing on trends in popular culture, science, and national politics to promote votes for women. During the era that historians categorize as the doldrums, suffragists began to connect their cause to scientific cooking. The home economics emphasis on modernization, rationality, and the elevation of women's work dovetailed with suffragists’ concerns about the public and private status of women. Unlike many food reformers at the turn of the century, however, suffragists intentionally politicized food. They did so, specifically, by using municipal housekeeping arguments to insist that women needed to use their domestic skills and expertise to improve both private and public conditions—from garbage removal and sanitation, to clean air and safe parks, to the quality and safety of food. More than informed citizens, suffragists argued women needed the franchise as wives and mothers to care for their families. By the turn of the century, suffragists around the country strategically countered antisuffrage claims with cookery rhetoric. By hosting bake sales, opening lunch carts, and organizing bazaars, suffragists put their domesticity and culinary capabilities on display for the hungry public. Although recipes for “spaghetti a la suffragette” and lunch wagons with “suffrage sundaes” used humor and whimsy to garner attention, suffragists remained focused on their goal—votes for women. By hosting bake sales, printing cookbooks, and sharing recipes, suffragists did not mistakenly embrace the trappings of domesticity. Rather, they recognized an argument consistently used against their cause and responded by constructing a new, and more socially acceptable, image of their movement.