Are media effects ephemeral and fleeting, subject to rapid decay and counter-frames (Druckman Reference Druckman2004; Druckman and Nelson Reference Druckman and Nelson2003)? Or are media effects deeply felt and enduring (Lecheler and de Vreese Reference Lecheler and de Vreese2012; Mendelberg Reference Mendelberg2001)? On one hand, extensive laboratory research has shown that the opinion formation and decision-making processes are susceptible to framing effects (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007a; Reference Chong and Druckman2013; Druckman Reference Druckman2004; Shen and Edwards Reference Shen and Hatfield Edwards2005). By focusing on different elements of a problem, these studies suggest that the media can prioritize different considerations and alter individual assessments of issues or candidates.

On the other hand, scholars have raised important concerns about existing studies. Are framing effects only signaling short-term changes to top-of-the-head responses (Zaller Reference Zaller1992)? Are the effects limited to questions that ask about views that are neither well thought out nor stable? Existing laboratory experiments are high on internal validity and an important part of the process of determining causal effects (McDermott Reference McDermott, Druckman, Green, Kuklinski and Lupia2011), but some have expressed doubts about the external validity of these laboratory experiments. Although they may disregard it in their considerations (Druckman and Leeper Reference Druckman and Leeper2012), respondents in the laboratory cannot tune out or ignore frames (Druckman Reference Druckman2001). Nor are they exposed to a volume and range of environmental interference that could drown out the framing (Druckman and Nelson Reference Druckman and Nelson2003). Most importantly, respondents in these experiments are generally not subject to counter framing (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007a; Reference Chong and Druckman2013). Perhaps not surprisingly, when studies of framing shift to the real world, effects are more limited or even negligible (Druckman and Nelson Reference Druckman and Nelson2003; Gerber et al. Reference Gerber, Gimpel, Green and Shaw2011; but see Kellstedt Reference Kellstedt2003; Mendelberg Reference Mendelberg2001). In addition, while the effect of framing on issue positions is still debated, to our knowledge, no study of framing effects has demonstrated meaningful shifts in core political identities and predispositions at the aggregate level.

This paper has two goals. First, we seek to help explain the divergent findings between framing effects in the laboratory and in the real world. Second, we want to highlight the potential of framing to induce meaningful shifts in core political identities and predispositions—shifts that could alter the partisan balance of power in American politics. To do this, we focus on media coverage of immigration and assess the effects of that coverage on aggregate white partisanship.

Immigration is an issue that we believe has unique attributes and thus is particularly well suited to induce large-scale change in partisanship. For most issues, there are vocal champions on both sides of the debate. But on immigration, there is growing evidence that media coverage and partisan debates present a largely negative image of immigration (Chavez Reference Chavez2008; Dunaway, Branton, and Abrajano Reference Dunaway, Branton and Abrajano2010; Merolla, Ramakrishnan, and Haynes Reference Merolla, Ramakrishnan and Haynes2013). If the preponderance of coverage presents only one side of the story, then framing might have more profound aggregate effects.

To assess the influence of media frames on immigration, we measure and gauge the impact of all immigration coverage in the New York Times (NYT) between 1980 and 2011 on quarterly white macropartisanship compiled over the same period from CBS/NYT polling. We find that immigration frames have a substantial impact on partisanship. Negative frames of immigration lead to greater white ties to the Republican Party and a reduced likelihood of identifying as Democrats. Overall these findings suggest powerful, wide-ranging effects of framing.

THE MEDIA AND FRAMING EFFECTS

Many contend that how issues are framed and presented in the news can influence voters' evaluations of those issues as well as evaluations of political actors associated with those issues (Iyengar Reference Iyengar1987). Chong and Druckman (Reference Chong and Druckman2007b) define framing as “the process by which people develop a particular conceptualization of an issue or reorient their thinking about an issue.” Because of cognitive limitations, individuals organize concepts thematically and can only retain a finite number of important considerations in the forefront of their minds. The media or other actors influence opinions by privileging some considerations over others (Zaller Reference Zaller1992).

Scholars have marshaled impressive evidence in favor of this framing effects hypothesis. We highlight two different types of documented framing effects here.Footnote 1 First and perhaps most basically, framing can alter the way we see an issue by privileging one aspect of a problem over another or altering the group imagery associated with an issue (Nelson and Kinder Reference Nelson and Kinder1996). This occurs when media coverage causes individuals to focus considerations on a subset of relevant considerations when formulating opinions (Druckman Reference Druckman2004). For example, experimental studies show that support for welfare changes depending on whether coverage highlights work requirements or need (Shen and Edwards Reference Shen and Hatfield Edwards2005). Likewise, variations in media coverage of race relations change the public's racial policy preferences over time (Kellstedt Reference Kellstedt2003). Critically, Merolla, Ramakrishnan, and Haynes (Reference Merolla, Ramakrishnan and Haynes2013) show that issue framing can affect attitudes on immigration. Given that most Americans think the majority of immigrants lack legal status, the crime frame may be especially powerful at priming a subset of considerations used in the formation of opinions (Enos Reference Enos2012).

Similarly, by focusing repeatedly on a particular group, news coverage can lead to evaluations of issues based on attitudes towards the group in question rather than the issue at hand (Gilens Reference Gilens1999; Nelson and Kinder Reference Nelson and Kinder1996). If the group highlighted is associated with negative stereotypes or perceived as a threat to the respondent's social group—as is often the case with racial and ethnic minorities—news coverage can lead to more limited public support for certain policies (Gilliam and Iyengar Reference Gilliam and Iyengar2000; Gilliam et al. Reference Gilliam, Iyengar, Simon and Wright1996; Outten et al. Reference Outten, Schmitt, Miller and Garcia2012).

The other category of framing is more direct. The media affects our evaluation of issues simply by altering the tone of coverage (Hester and Gibson Reference Hester and Gibson2003). Tone evokes feelings that directly influence one's evaluation of an issue (Lodge and Taber Reference Lodge and Taber2013), or biases the set of considerations stored in or retrieved from memory (Zaller Reference Zaller1992). Coverage that is more negative in tone and that highlights undesirable features of a phenomenon rather than positive attributes can limit support for that phenomenon.

THE MINIMAL EFFECTS VIEW

There are, however, those who question the extent of framing's impact (Druckman Reference Druckman2004). Most of our understanding about the influence of framing has emanated from experimental research conducted in settings where individuals receive only a single frame in a single exposure. These laboratory studies are critical because of their high internal validity and their ability to demonstrate causal connections (McDermott Reference McDermott, Druckman, Green, Kuklinski and Lupia2011), but critics have highlighted limitations of this format and raised concerns about external validity.

One concern is that the effects of framing tend to be ephemeral or fleeting. When tested immediately after being exposed to a particular frame, subjects display distinct views. But the effects of framing erode quickly over time. When the subjects are queried a day, a week, or a month later, few significant results emerge (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007b).

Other issues relate to the unrealistic nature of laboratory settings where most framing experiments are run. When studies of framing switch to natural settings, evidence of framing becomes more limited in its impact and scope (Druckman Reference Druckman2004; Druckman and Nelson Reference Druckman and Nelson2003; Gerber et al. Reference Gerber, Gimpel, Green and Shaw2011; but see Rose and Baumgartner Reference Rose and Baumgartner2013; Dardis et al. Reference Dardis, Baumgartner, Boydstun, De Boef and Shen2008; Kellstedt Reference Kellstedt2003). In the laboratory, subjects generally receive limited stimuli, all of the “noise” of daily life is blocked out, and there is little to focus on other than the frame. Studies indicate, however, that more information reduces the effect of any one frame (Druckman and Nelson Reference Druckman and Nelson2003). Relatedly, subjects in these experiments do not control the frames or media outlets to which they are exposed. Framing effects in the real world may be more limited because citizens selectively screen out frames (Druckman Reference Druckman2001) and ignore frames or sources they do not trust (Lupia and McCubbins Reference Lupia and McCubbins1998). Finally, and we believe most importantly, subjects typically do not receive counter-frames as they would in most political debates. If only one side speaks, it is likely to be powerful and effective. In contrast, recent experimental studies that present counter-frames show little to no overall effects (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2013; Druckman Reference Druckman2004). As a result, it is uncertain just how much framing matters in the real world.

One final limitation of existing research is that studies about framing have focused almost exclusively on the opinions individuals have about specific policy issues. However, as many scholars have demonstrated, individual positions on most issues are not well thought out and are often highly volatile (Converse Reference Converse and Apter1964). If issue positions are not deeply held and change regularly over time, it may be easy to find effects of framing. Simply, issue positions represent an easy case for media and framing effects.

IMMIGRATION AND PARTY IDENTIFICATION

We seek to offer a better understanding of the nature and efficacy of framing effects in the real world. We do so by focusing on the connection between framing on immigration and aggregate partisanship in the United States. Immigration has a range of unique attributes that provide a telling test of real-world framing effects. Compared with other issues, media portrayals of immigration are more one-sided and negative (Chavez Reference Chavez2008). If one key to framing effects in the real world is the relative balance of messages, then a study of immigration could prove to be revealing.

Many studies of immigration coverage are anecdotal but there is growing evidence that media overwhelming focus on an “immigrant threat” narrative that links immigration to economic costs, social dysfunction, illegality, and cultural decline (Dunaway, Branton, and Abrajano Reference Dunaway, Branton and Abrajano2010; Merolla, Ramakrishnan, and Haynes Reference Merolla, Ramakrishnan and Haynes2013). The perception of threat can have a significant effect on an individual's policy preferences. In the aftermath of terrorist attacks, or in situations where mortality is made salient, individuals are more likely to endorse conservative policies and support conservative leaders (Nail et al. Reference Nail, McGregor, Drinkwater, Steele and Thompson2009; Ulrich and Cohrs Reference Ulrich and Cohrs2007). These effects, however, are not limited to physical threats (Cotrell and Neurberg Reference Cotrell and Neurberg2005). Indeed, new research demonstrates that the salience of racial demographic shifts influences partisanship (Craig and Richeson Reference Craig and Richeson2014a) and concern about immigration is now a primary driver of changes in individual partisanship (Hajnal and Rivera Reference Hajnal and Rivera2014).

There are also a number of other features of immigration that suggest it could be especially powerful in shaping partisan attachments on the macro level. Like other issues that have led to realignment or substantial partisan change, immigration is simple, symbolic, and salient (Carmines and Stimson Reference Carmines and Stimson1989; Layman and Carmines Reference Layman and Carmines1997). Equally importantly, the two major parties have staked out increasingly divergent positions on immigration over the last two decades (Jeong et al. Reference Jeong, Miller, Schofield and Sened2011; Wong Reference Wong2013). All of this means that there is real potential for framing to impact attitudes on immigration and for immigration to shape white partisanship.

With that in mind, we offer a relatively straightforward test of real-world immigration framing on partisanship. We guage the impact of framing in all NYT stories on immigration on aggregate party identification measured quarterly over the roughly 30 year period for which immigration has been on the nation's agenda in modern times. The basic test is to see if more negative framing of immigration leads to shifts toward the Republican Party—the Party associated with more restrictionist immigration policies.

This test adds to our understanding of framing effects in three important ways. First, we hope to offer a more discerning test of framing by assessing the impact of the media, not in quiet confines of the laboratory, but in the real world, where multiple frames and multiple voices are possible and where individual Americans can choose to listen to or tune out. Second, by focusing on an emerging issue that is subject to disproportionate amounts of negative framing, we hope to better understand the factors that explain when framing matters and when it does not. Third, we hope to demonstrate how powerful framing can be in shaping core elements of the political process and the balance of power within a polity. By focusing on party identification rather than issue positions, we put forward a particularly tough test of media effects. Issue positions, which have been the subject of most of the previous framing effects literature, tend to be relatively unstable and malleable at the individual level (Converse Reference Converse and Apter1964; Feldman Reference Feldman1988, but see Ansolabehere, Rodden, and Synder Reference Ansolabehere, Rodden and Synder2008). In contrast to opinions, party identification is viewed as one of the most immovable objects in American politics (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960; Goren Reference Goren2005; Green et al. Reference Green, Palmquist, Schickler and Bruno2002). Moreover, party identification is not only durable, it is impressively potent—the “unmoved mover” that drives almost everything in American politics.Footnote 2 If we find media effects here, we will have greatly expanded our understanding of how media influences politics. Likewise, by focusing on aggregate partisanship rather than on individual partisan decisions, we can see how framing affects the overall balance of power in American politics. It is one thing to shift the political orientations of a small number of individuals. It is quite another to sway a nation in one direction or the other. In short, we hope to not only learn more about when framing matters, but also about how broadly and deeply framing can matter.

DATA

To assess the effects of news media coverage on immigration, we analyzed the volume and content of all articles from the NYT between 1980 and 2011 that mentioned immigration—almost 7,000 in total. Using the LexisNexis database of newspapers, we searched the following terms: immigration, immigrant, immigrants, migration, etc.Footnote 3

We selected the NYT for two reasons. First, we were interested in an outlet that provides national coverage and readership. The NYT has the second largest circulation in the United States, at approximately 1.86 million and reaches a nationwide audience. Second, as a more liberal news outlet, the NYT is an especially difficult test of our hypothesis that media focuses on an “immigrant threat” narrative. The NYT is a new outlet that would be much less likely to propagate the immigrant threat narrative. If a mainstream, liberal news outlet has fallen prey to using the immigrant threat narrative, then it is likely that other media outlets, especially those with a conservative bent, would see a much larger share of their immigration news stories adopting this narrative.

Our choice to focus on newspaper articles, as opposed to television news programs, was motivated by the amount of information that can be gained from newspapers as opposed to televisions news. A typical television segment about immigration is, at best, 20–30 s in length. As our theory and hypotheses focus specifically on the media frames, newspapers offer much more content to assess these frames than does broadcast news. It is, however, worth noting that our results are unlikely to differ from analysis of television news coverage. The volume and content of national political news coverage on television is remarkably similar to coverage in the NYT (Durr, Gilmour, and Wolbrecht Reference Durr, Gilmour and Wolbrecht1997; Hassell Reference Hassell2014). We focus on the time frame from 1980 to 2011 since this is roughly the period where immigration has been on the nation's agenda.

Based on the existing framing literature as well as studies specifically focused on the immigrant threat narrative, we coded the NYT stories across three dimensions of framing: tone, issue content, and immigrant group mentioned. The most subjective of these frames is the tone of the news story. We grouped stories by whether the story provided a positive, negative, or neutral account of immigration. Our coders judged an article to be negative if the primary focus of the article was problems associated with immigration; for example, an article about an arrested immigrant was coded as negative. Likewise, articles focusing on the benefits of labor migrants to the national economy were coded as positive. Negative and positive tone was also derived from the overall conclusions presented in the article. If, for example, the article appeared to be critical of politicians or organizations that supported immigrants' rights, it was coded as negative. The coders identified neutral tone when the article gave no preference for either side of a policy.

Issue content coding was more straightforward. Coders examined whether the newspaper article focused on crime, economic issues, homeland security, and/or immigration policy. We expect stories focused on crime, the economy, and security to frame immigration negatively. In contrast, we expect stories about policy solutions to immigration to frame immigration in a neutral or positive light. Many stories also highlighted positive externalities associated with immigration and the proposed policy solutions. For this particular area of coding, a news story could be coded as containing up to three issues.

Finally, we coded for the particular immigrant group featured in the article. We noted stories that mentioned Latinos, Hispanics, or immigrants from Latin America, those stories that referred to Asian Americans or Asia, and those that highlighted immigration from Europe or other regions. More than one immigrant group could be mentioned in the article. We must also note that these three types of frames (tone, issue content, and immigrant group) are not mutually exclusive; that is, an article featuring a Latino immigrant could discuss crime and the economy, and also adopt a negative tone. We aggregate these frames by quarter. Thus, an example, we would assess the proportion of articles over a given time period that mention Latinos. For tone, we take the proportion of articles that are negative versus those that are positive in nature.

Due to concerns about the subjective nature of some of this coding, we performed the coding using two distinct methods. Newspaper articles were coded using research assistants and machine coding. The automated content analysis used machine-learning techniques and the text classification package, Rtexttools (Jurka et al. Reference Jurka, Collingwood, Boydstun, Grossman and van Atteveldt2012), and incorporated information from the hand-coded articles before 2000. Tests of intercoder reliability between the automated dataset and the hand-coded dataset reveal a high degree of agreement. Moreover, the results of the following analysis are consistent across the two different coding methods. How we code the articles makes little difference. We include details on each method and a comparison of the two in the online Appendix.

HOW IS IMMIGRATION FRAMED?

In order to assess the media's role in framing immigration and its effects on white partisanship, we first have to determine what the media reports on immigration. Are the frames that are used to discuss immigration disproportionately negative? Are they overwhelmingly centered on Latinos? And are they focused more on problematic policy issues such as crime and terrorism than on positive topics such as families and assimilation?

There are strong assertions, as well as a growing body of evidence that media portrayals of immigration are, in fact, negative (on metaphors and message see Chavez Reference Chavez2008; Brader, Valentino, and Suhay Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008; for a more systematic approach see Merolla, Ramakrishnan, and Haynes Reference Merolla, Ramakrishnan and Haynes2013; Valentino, Brader, and Jardina Reference Valentino, Brader and Jardina2013). Our data collection effort significantly improves upon existing studies by offering more detailed information on the content of framing and by assessing news stories over an extended period.

Before distinguishing between the different frames employed in immigration news coverage, it is worth briefly assessing the total amount of coverage on immigration. Altogether, we identified 6,778 articles on immigration between 1980 and 2011. That is roughly 227 articles per year—arguably enough coverage to make the issue salient and to potentially sway opinions.Footnote 4 There is considerable variation in the volume of immigration coverage across this timespan, but the most obvious pattern is the increasing attention to immigration over time. We see a clear spike in coverage in 2006 likely related to the introduction of the Sensenbrenner Bill (HR 4437), which increased penalties for undocumented immigrants and sparked protests from immigrants' rights supporters across more than 140 cities and 39 states.

As we expect, we find that that news coverage generally follows the immigrant threat narrative. Most of the frames used to describe immigrants are negative ones. By the overall tone of stories, there are four times as many negative news stories on immigration as there are positive news stories. All told, 48.9% of immigration news articles adopt a negative tone. By contrast, only 12.1% of immigration news stories frame immigrants in a positive manner. The remaining news stories, 39%, take on a neutral tone.Footnote 5

The immigrant group depicted in news coverage of immigration is equally lopsided. Fully 65.5% of all immigration articles mention Latinos immigrants. By contrast, only 26.3% of stories reference immigrants from Asian countries and fewer still focus on immigrants hailing from Europe, Russia and Eastern Europe, or the Middle East. All of this is consistent with the composition of immigrants in the United States but it, nevertheless, highlights how prevalent the Latino immigrant frame is in news stories (see also Valentino, Brader, and Jardina Reference Valentino, Brader and Jardina2013). Because images of Latinos spur negative associations among white Americans (Outten et al. Reference Outten, Schmitt, Miller and Garcia2012; Valentino, Brader, and Jardina Reference Valentino, Brader and Jardina2013) this coverage could have consequences for partisan ties.

We now move on to examine the issue content of these immigration articles. Among all of the different issues that could be associated with immigration, the NYT most frequently framed immigration with the economy. Approximately 25% of immigration news articles adopted this frame. The next most commonly used frame discussed immigration in the context of some aspect of immigration policy. About 20% of the news stories featured these frames. Crime was associated with only 9% of all immigration news stories, perhaps less than the immigrant threat narrative would suggest. Finally, national security frames were used very rarely, only about 1.8% of the time.Footnote 6 Given the predominantly negative view of immigrants' contributions to the economy, crime, and national security, we expect these frames to have negative consequences, while policy solutions frames might be neutral or even have positive effects.

All told, when the public consumes media dealing with immigration, a scant few find news that portrays immigrants in a positive light. The immigrant threat narrative, as previous accounts have argued, is prevalent (Chavez Reference Chavez2008; Valentino, Brader, and Jardina Reference Valentino, Brader and Jardina2013). Given that we will be analyzing changes over time, it is important to note that each of these different immigration frames varies over time. Figures A1–A3 in the Online Appendix illustrate wide temporal variation in the total amount of coverage devoted to immigration as well as the extent that it focuses on Latinos and the tone it employs. However, consistent with the immigrant threat hypothesis, although it does vary over time, coverage generally highlights negative aspects of immigration. This skewed coverage makes it difficult for Americans to consider the full spectrum of immigrants' contributions to society. This predominantly negative coverage has the potential to fuel fears—fears that could shift white Americans toward the Republican Party.

IMMIGRATION FRAMES AND WHITE MACROPARTISANSHIP

The patterns presented so far highlight the prevalence of the immigrant threat narrative and hint at the role that media coverage could have played in driving white Americans to the Republican Party. In this next section, we directly assess the link between media coverage of immigration and white macropartisanship. We focus on the partisanship of white Americans because they are more concerned about and more opposed to immigration than either Latinos or Asian Americans (Polling Report 2013). As such we suspect that white Americans tend to respond differently to the issue of immigration and framing on immigration than other racial and ethnic groups. In contrast, members of primarily immigrant-based groups Latinos and Asian Americans may feel personally attacked at media frames that highlight negative aspects of immigration (Perez Reference Perez2015).Footnote 7

Such an analysis requires us to collect data on partisan preferences from the same period of time as our media data (1980–2011). To gather our party identification data, we turn to the CBS/NYT poll series.Footnote 8 This poll series is unique in that it contains a considerable amount of data over regular intervals of time. Importantly, the CBS/NYT series asks the standard party identification question: “Generally speaking do you usually consider yourself a Democrat, Republican, or what?” Altogether, 488 surveys include a question on party identification during our period of interest.Footnote 9 As our focus is on white Americans, we exclude respondents who self-identify as non-whites. On average, there are 934 non-Hispanic white respondents in each survey.Footnote 10 The average number of surveys per year is 18.Footnote 11 These data allow us to assess white partisanship accurately and examine the effects of immigration coverage on partisanship. Mirroring Mackuen and Erikson (Reference MacKuen and Erikson1989) and their work on macropartisanship, we calculate the mean responses from each survey and aggregate by quarter.

Figure 1 plots the percentage of Democratic Party identifiers spanning from 1980 to 2011. The graph reveals two important patterns in aggregate white partisanship. First, over time there is a decrease in Democratic identifiers. White attachment to the Democratic Party falls from a high of 43% in 1980 all the way down to about 28% in 2010.Footnote 12 As attention to immigration has grown, support for the Democratic Party has declined.Footnote 13 Subsequent analysis will show that these gains accrue both to Independents and the Republican Party. Second, despite the widespread view that party identification is stable, there is quite a bit of variation over time. Overall, our examination of white macropartisanship squares well with the existing evidence presented by MacKuen and Erikson (Reference MacKuen and Erikson1989) and others (Erikson et al. Reference Erikson, MacKuen and Stimson2002).

Figure 1. Percentage of Democratic identifiers, 1980–2011

Can the “immigrant threat” narrative help explain some of this movement in white partisanship? We turn to an analysis of the connection between immigration news framing and macropartisanship. The dependent variables of our models of macropartisanship are the percentage of those who identify as Democrats, the percentage who identify as Independents in response to the first party identification question, and the percentage who identify as weak Republicans.Footnote 14 Our primary explanatory variables of interest are those capturing the different framing dimensions used in immigrations news coverage. Specifically in terms of framing we evaluate the tone of the coverage (as measured by the ratio of negative to positive news), the use of the group centric frame (as measured by news stories focusing on Latino immigrants), and the proportion of stories that use the crime and economy issue frame.

Immigration frames are not, of course, the only factors that could drive aggregate partisanship. The two main documented sources of change in macropartisanship are experiences with the party in power and current national economic conditions (Erikson et al. Reference Erikson, MacKuen and Stimson1998; Fiorina Reference Fiorina1981; MacKuen and Erikson Reference MacKuen and Erikson1989). The former is conventionally measured with presidential approval and the latter with the national unemployment rateFootnote 15 (Erikson et al. Reference Erikson, MacKuen and Stimson1998; MacKuen and Erikson Reference MacKuen and Erikson1989). To help ensure that these other factors are not driving our immigration framing results, we include both aggregate presidential approval and national unemployment in our model.Footnote 16 Finally, we also include the total number of stories on immigration to account for the possibility that agenda-setting could also influence the partisan attachments of white Americans.Footnote 17

We performed a series of diagnostic tests to assess the properties of our time series. First, we performed the Phillips–Perron test where the null hypothesis is that the series has a unit root with a change in its level.Footnote 18 The alternative hypothesis is that the series is stationary with a structural break. We tested this using an additive outlier (AO) model, which is appropriate for a sudden change in the series. The model utilizes an endogenous selection procedure wherein the break date is selected when the t-statistic for testing unit roots is minimized. To assess the robustness of the results, we also implemented the test using an innovational outlier (IO) model (which is appropriate for a gradual change).Footnote 19 The result from this test indicates that the presence of a gradual change should be rejected at the p < .01 level. Finally, we checked for the possibility of multiple breaks using the Clemente, Montañes, Reyes unit root test (Clemente, Montañés, and Reyes Reference Clemente, Montañés and Reyes1998). The results indicate that the presence of multiple breaks should be also rejected at the p < .01 level.Footnote 20

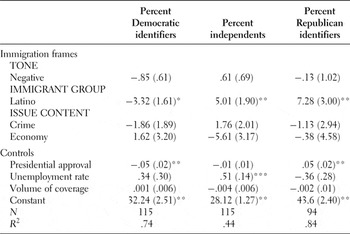

As with most time-series data, we were unable to reject the null of no serial correlation, using the calculated the Durbin–Watson test statistic. Thus, we initially estimate our time-series data using Prais–Winsten AR(1) regressions, which assumes that the errors follow a first-order autoregressive process.Footnote 21 Table 1 looks to see if immigration coverage predicts changes in aggregate partisanship.

Table 1. The effect of immigration frames on white partisanship

**p < .01,*p < .05.

Coefficients are Prais–Winsten AR(1) regression estimates. Standard errors in parentheses.

As expected, the immigrant threat narrative is strongly linked to white macropartisanship. The more stories that focus on Latino immigrants, the more likely whites are to subsequently shift away from the Democratic Party and the more likely they are to identify as independents or Republicans. The model predicts a 0.7 percentage point increase in white Republican identifiers when NYT coverage of immigration focusing on Latinos increases by ten percent. A similar increase in Latino frames reduces the proportion of white Democratic identifiers by about 0.3%. As hypothesized, the immigrant threat narrative, as construed via frames that focus on Latino immigrants, activates the fears that many in the public have over immigration, making them less likely to affiliate with the party traditionally more sympathetic to immigrants.

We also considered the possibility that group-centric frames, which focus on the second largest immigrant group in the United States, Asians, may provoke the same reaction among white Americans. As such, we also performed an analysis that includes Asian-immigrant frames. It does not have the same effect on macropartisanship as Latinos immigrant frames does. That is, the coefficient capturing Asian-immigrant frames fails to achieve statistical significance at conventional levels.Footnote 22 As existing research suggests, Asian immigrants do not elicit the same the kinds of anxiety and fears that Latino immigrants generate, either due to the way Latinos are covered by the media (Chavez Reference Chavez2008) or the differential stereotypes that are associated with each group or both (Chavez Reference Chavez2008; Kim Reference Kim1999).

These findings suggest two conclusions. First, framing effects may be more powerful than previously suggested. Real shifts in party identification—the unmoved mover of American politics—appear to be linked to how the media covers immigration. If the framing of news stories can affect the national balance of power between Democrats and Republicans, it is a formidable shaper of political behavior. Second, the immigrant threat narrative is a potent frame. Stories that highlight Latino immigrants activate the fears of large segments of the public and generate enough anxiety to sway partisan attachments.

However, the remaining estimates presented in Table 1 also indicate that not everything that the media puts forward resonates with the public enough to alter partisan identities in a measurable way. Existing research on the media framing of African-Americans suggests that crime frames can be an effective tool in shaping white views (Gilliam and Iyengar Reference Gilliam and Iyengar2000; Gilliam et al. Reference Gilliam, Iyengar, Simon and Wright1996). This coefficient is, not, however, statistically significant in our model. The proportion of immigration-related stories that focused on crime is unrelated to subsequent white partisanship. Moreover, when we controlled for other immigration issue frames in the model, the main results remain largely unchanged.Footnote 23 More coverage featuring border security or terrorism frames also had no appreciable effect on aggregate white partisanship. Likewise, greater media attention to the impact of immigration on the economy did not push white partisanship one way or the other. There were signs, albeit weak ones, that when the NYT focused specifically on immigration policy frames, white Democratic identity increased. But we could find no link between immigration policy coverage and changes in identity as an Independent or Republican. All told, issue-specific frames seem to matter little in explaining white partisanship.

There was also no evidence that agenda setting is appreciably associated with aggregate partisanship. An increase in the number of immigration-related news stories may increase the perceived salience of this issue to the public but, as Table 1 reveals, there is no indication that it leads to systematic shifts to one party or another. In many circumstances, agenda setting is one of the most powerful tools in a democracy, but it appears to be relatively unimportant for this study of partisanship. It is the content of the coverage, not the volume of coverage that matters here.

ROBUSTNESS CHECKS

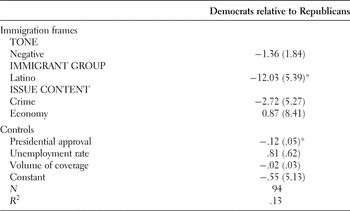

To increase confidence in our conclusions, we conducted a series of robustness checks altering the analysis in various, hopefully informative ways.Footnote 24 First, rather than focusing separately on the number of Democrats, Independents, and Republicans in the population, we created a series of measures of overall partisanship that either measured the ratio of Democratic identifiers and leaners to Republican identifiers and leaners or focused on the absolute difference in the proportion of Democratic and Republican identifiers. The pattern of results was the same. As Table 2 shows, regardless of how we measure macropartisanship, news coverage of Latinos is associated with significant and substantial shifts to the partisan right.

Table 2. The effect of immigration frames on white macropartisanship dependent variable: democrats relative to republicans

**p < .01,*p < .05.

Coefficients are Prais–Winsten AR(1) regression estimates. Standard errors in parentheses.

We also looked to see if altering how we measure key independent variables makes any difference. Specifically, in alternate tests rather than measure the percentage of stories that focus on each immigration frame, we focused on the total number of stories that employed each frame. Once again, our story was unchanged. Group centric images continued to be central, while tone and issue context were not relevant to white partisan choices.

We do, however, arrive at some more interesting and novel findings if we interact the tone of coverage with the total amount of immigration coverage. Essentially, we find that tone matters more when immigration gets lots of coverage. In other words, the more overall coverage, the more negative coverage leads to declines in Democratic Party identity. This suggests that when the immigration issue is particularly salient the tone of the coverage can matter. This is, however, a very tentative finding as the interaction between tone and total coverage is only marginally significant when added to one of the models in Table 1 (the proportion Democratic) and is insignificant in the other two cases.Footnote 25

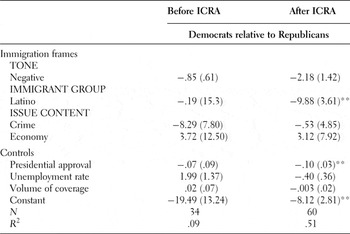

One might also wonder whether the partisan effects of immigration framing have increased in recent decades when the Republican and Democratic Parties have been more polarized on immigration policy. It is hard to pinpoint an exact date for the divide since partisan divisions on immigration appear to evolve differently at different levels. One could argue that there was not a significant partisan gap on immigration at the presidential level until the 2012 election, but also note that partisan divisions on immigration were well entrenched in California in the early 1990s (e.g. Proposition 187). We choose to separate out our analysis into periods pre- and post the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA). IRCA, which was signed into law by President Reagan, is a seminal moment not only in that it generated the nation's largest scale legalization effort but also represents that last bi-partisan effort to pass major immigration legislation. We look to see if immigration framing has more partisan consequences when the parties diverge after 1986. As Table 3 illustrates, we find no effect of framing prior to IRCA.

Table 3. The effect of immigration frames on white macropartisanship. before and after ICRA

**p < .01,*p < .05.

Coefficients are Prais–Winsten AR(1) regression estimates. Standard errors in parentheses.

In more recent years, however, the Latino immigrant frame in the media exerts a statistically significant and substantial effect on partisanship. This is further evidence that the real-world political effects of framing depend on context.

The test in Table 3 is important for a second reason. The fact that white Republican identity and media attention to immigration both increase substantially from 1980 to 1986 raises the possibility of spurious correlation. However, since most of the shift in white partisanship occurs by 1986, we can assuage concerns about spurious correlation by dropping this time period and re-running our analysis, as we do in Table 3. This analysis strengthens confidence in the relationships since it shows that frames matter even after the large-scale shift to the Republican Party occurred.

OTHER POLICY ISSUES

Perhaps a deeper concern is that by restricting over attention to immigration and ignoring media coverage of other salient issues, we are unfairly biasing our results in favor of significant findings. To address this concern, we collected and incorporated data on NYT coverage of welfare, terrorism, and war—three issues that received widespread coverage over this period of time and three issues that many might view as being primarily responsible for Republican gains over the same period. Our coding scheme was similar but due to time constraints we used machine coding for all articles about these three other issues.Footnote 26 As before, we looked at both the tone of the articles (the average balance of negative versus positive words) and the total amount of coverage devoted to each issue each quarter.

The results of the analysis, which can be found in the online Appendix, demonstrate that the incorporation of other salient issues does not alter our main findings. Immigration coverage continues to help explain shifts in aggregate partisanship. There are also some weak signs that more positive coverage of terrorism increases the percentage of white Americans who identify with the President's Party, but the effects are not at all robust across the different dependent variables.

OTHER TIME-SERIES MODELS

In line with DeBoef and Keele (Reference DeBoef and Keele2008), we sought to reanalyze our data with a different time-series model to confirm the basic pattern of findings. Specifically, we repeated the analysis with an error correction model (ECM). The ECM analysis which is also displayed in the online Appendix again confirms our core conclusion. A greater focus on Latinos is related to a rightward shift in partisanship. The ECM is also helpful in that it can help us to say something about the short- and long-run effects of immigration coverage. The ECM indicates that immigration media coverage has both a significant temporary effect and a significant long-run impact. Specifically, the ECM estimates that a ten percent increase in NYT coverage of Latinos is associated with an immediate 1.6 point shift in the balance of Democrats and Republicans in the nation and a 1.4 point long-term shift in the partisan balance.Footnote 27 Calculating the long run multiplier, the ECM estimates that a ten percent increase in NYT coverage of Latinos is associated with a 3.6 point shift in the partisan balance over all future periods.

UNDERSTANDING THE MECHANISM

To this point, we have tied attitudes on immigration to changes in partisanship, but we have yet to demonstrate how that connection is made. We believe that negative media portrayals of immigration get Americans to think differently about immigration. Specifically, the immigrant threat narrative put forward in the media should increase anxiety about immigration and lead to lower levels of support for immigration. Once Americans feel more concerned about immigration and view immigrants more negatively, they should begin to be more attracted to the Republican Party and its anti-immigration policies.

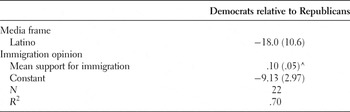

We attempt to test this pathway by incorporating aggregate attitudes about immigration into our empirical model. If we are right, by adding immigrant attitudes to our model, we should account for and eliminate the effects of media framing and we should see a clear connection between immigrant attitudes and macropartisanship.

In theory, the test is straightforward. In reality it is difficult to find any measure of immigration views that is asked repeatedly over our time period. Our admittedly imperfect solution is to use every question in the Roper Center Archives that ask whether “immigration” should be “increased,” “decreased,” or “kept at its present level.” To get aggregate opinion, we subtract the portion that favors an increase from the portion that favors a decrease in each quarter. Even combining responses from different survey firms, the number of quarters for which we have useable data drops from 94 to 22. Since we have a small N problem, we are forced to limit the analysis to two key independent variables—the one immigration frame that we found to be tied to macropartisanship in our earlier tests and mean immigration opinion. As well, we have to be extremely cautious about how forcefully we interpret our results.

Nevertheless, our findings do match our theory and expectations. When we add mean immigration opinion to our model, the direct link between media frames and macropartisanship fades away. More importantly, we find a relationship between mean immigrant opinion and macropartisanship.Footnote 28 The more negatively white Americans feel about immigration, the more likely whites are to subsequently shift away from the Democratic Party toward the Republican Party. The size of the effect is far from massive, but it is meaningful. The model predicts a four-point shift in aggregate white partisanship when there is a one standard deviation (SD) shift in immigration views. Again, given the small N, these results should be interpreted with a healthy dose of skepticism, but they do appear to add to our understanding of how media frames are linked to party identification (Table 4).

Table 4. Immigration frames and white macropartisanship the mediating role of aggregate immigration opinion

**p < .01,*p < .05 ^p < .10.

Coefficients are Prais–Winsten AR(1) regression estimates. Standard errors in parentheses.

In addition, it is also important to add that we are not the first to find an empirical link between immigration attitudes and partisanship. Hajnal and Rivera (Reference Hajnal and Rivera2014), Bowler, Nicholson, and Segura (Reference Bowler, Nicholson and Segura2006), and Nicholson and Segura (Reference Nicholson, Segura, Segura and Bowler2005) all show in different ways that concerns about immigration have at times led to shifts in partisanship. One might even point to Donald Trump's surge in the Republican primary polls from near last place to first place in the summer of 2015 as evidence of the power of immigration. Trump's massive gain in popularity occurred immediately after his negative comments on Mexican immigrants, crime, and rape. Those comments were widely reported in the media and indeed almost three quarters of Trump coverage during that period focused on immigration (Parker Reference Parker2015). More broadly, outside of the immigration case, there is ample evidence that issue positions can and often do drive changes in partisanship (Carsey and Layman Reference Carsey and Layman2006; Dancey and Goren Reference Dancey and Goren2010; Highton and Kam Reference Highton and Kam2011).Footnote 29 It therefore seems more than plausible that immigration could re-shape American politics.

IS IT REALLY THE NYT?

One legitimate concern that skeptics might raise is whether immigration coverage by the NYT can in and of itself really have this sort of impact on partisanship. After all, newspaper readership has been increasingly on the decline in the time period we examine. We, in fact, have no doubt that the NYT cannot do all of this alone. We believe that the immigrant threat narrative is being driven by a wide array of media outlets and that the NYT is a simple stand-in for those other outlets. Indeed, robustness checks indicate that immigration coverage in the NYT over this period mirrors that of other news outlets. Specifically, when we analyzed TIME magazine and US News and World Report magazine immigration coverage and used the same coding scheme as the one used to analyze the content of the NYT, we find a similar trend in terms of the volume and tone of coverage. In both alternative outlets, most of these news stories adopt a negative tone. For instance, 72% of all immigration articles from US News and World Report are negatively framed, and for TIME magazine, this percentage is even greater at 88.7%.Footnote 30 As we mentioned before, there is also existing evidence that NYT coverage on other issues closely matches other print coverage and television coverage (Durr, Gilmour, and Wolbrecht Reference Durr, Gilmour and Wolbrecht1997; Hassell Reference Hassell2014). Thus, we believe that the effects on macropartisanship that are evident here are the cumulated effects of the entire range of media coverage at different points in time. The NYT may not be powerful enough to influence the partisan balance of power on its own but the media as a whole is capable of doing just that.

ONE LAST CONCERN

One could also question a different aspect of the causal story. Cynics about media framing might argue that the media is simply reporting real-world events and it is the events rather than the media itself that is driving changes in white partisanship. To a certain extent we believe that is probably true. Events like the immigrants' rights protests around the country are certainly shaping the nature and extent of immigration coverage.

But we also offer two important rejoinders to the notion that real-world events are driving all of the results that we see here. First, we know that all media outlets have a bias in the news-making process (Graber Reference Graber1996), and no coverage of news is ever purely objective. Second, the media coverage of immigration is overwhelmingly negative yet academic studies of immigration show that immigrants today are assimilating just as rapidly as immigrants in the past and that the economic consequences of immigration are either positive or inconsequential for the vast majority of Americans (Alba and Nee Reference Alba and Nee2005; Bean and Stevens Reference Bean and Stevens2003).

The media has the choice of covering a complex, multi-faceted issue like immigration in any number of different ways. If the underlying story is a relatively positive one, why is the coverage negative? We suspect that because the news media outlets are primarily driven by profit (Hamilton Reference Hamilton2004), they are apt to favor negative stories because they garner attention; such stories drive up readership and in turn increase profit. Thus, even though the vast majority of Americans do not see or experience these events first-hand, the media plays a critical role in deciding what the public is exposed to. By choosing what to cover or not cover and how to cover it, the media can influences not only opinions, but also partisan identities in ways that are consequential to political outcomes.

Moreover, the balance of immigration coverage has focused more and more on Latinos over time. Figure 2 shows the average number of Latino frames in news coverage of immigration in the NYT over the course of the time period. The focus on Latino immigrants in has especially increased since 2007. Yet, in the same time period, immigration has shifted from Latin America to Asia, Mexican migration to the United States has plummeted, and the number of unauthorized immigrants has plateaued (Passell and Cohn Reference Passell and Cohn2016). Thus, we can be more confident that the effects we find are not the result of real immigration changes that affect attitudes, but rather are the result of changes in media coverage.

Figure 2. Proportion of Latino Immigrant Frames, by Year and Quarter

CONCLUSION

Our three decades long content analysis of a prominent national newspaper reveals that much of the news coverage of immigration promulgates a Latino threat narrative. Even within the liberal confines of the NYT, coverage is lopsided, emphasizes the negative consequences of immigration and focuses on Latino images. All of this fuels fears about immigration and shifts the core partisan attachments of white America to the right. After reading about the negative impact of Latino immigration, white America responds by identifying more with the Republican Party.

These patterns have important implications both for our understanding of framing and media effects and for our understanding of the place of immigration and race in American politics. First, for media framing, our results suggest that the media and framing may be more powerful than recent minimalist critics have argued (Druckman Reference Druckman2004). In our analysis, we have abandoned the isolated world of the laboratory in order to examine media and framing effects in the real world where individuals are exposed to a plethora of different messages across various formats—messages that they can miss in the dense media environment. We assess the effect of news coverage at one point in time on subsequent changes in white partisanship over a 30-year time span, while controlling for other factors that influence partisanship. Our findings indicate that the connection between news coverage and party identification is both clear and pronounced.

Our analysis differs from existing studies of framing effects in two other important ways. First, unlike previous studies that look for relatively short-term individual level shifts on specific issue positions, we focus on party identification, one of the most stable, deep-seated psychological attachments in the realm of politics. Partisan attachments are not fleeting, oft-altered top-of-the-head responses. Party identification is, for many Americans, something that arrives in early adulthood and rarely if ever changes. The fact that the group frames presented by the media predict changes in white partisanship indicates the powerful, wide-ranging effects that framing can have. Moreover, that these framing effects work at the aggregate level lead to real shifts in the balance of national partisan power only serves to reinforce the notion that media framing can change politics at its core.

We also garner some insight into the question of when framing matters. Why do we see such powerful media effects here when any number of recent studies has shown that framing has relatively little, long-term impact in the real world. We think the answer is that immigration may be a unique issue in American politics (Tichenor Reference Tichenor2002). For most issues there are vocal champions in the media on both sides. But as we have seen here, positive stories on immigration are relatively rare. Even in the liberal bastion of the NYT, negative stories on immigration outnumber positive stories four to one.Footnote 31 More than likely that ratio of negative to positive is more severe elsewhere. If the public is only exposed to one frame and no counter-frame, this frame can be powerful. Immigration coverage may have widespread effects because it is one-sided. Immigration may shift white Americans to the right because that one-sided coverage is predominately negative. At the same time, much more work needs to be done before we can answer this question with certainty. Immigration differs from other issues on several other dimensions. The highly salient and symbolic nature of immigration, the ambivalence that many white Americans feel about immigration could also help to shape the pronounced framing effects we see here.

The findings in this article hint at the growing role that immigration and race may be playing in American politics. What is striking about the patterns we present is not that immigration or race is relevant to American politics. We know that many white Americans have felt threatened by minorities and different immigrant groups across American history (Craig and Richeson Reference Craig and Richeson2014b; Tichenor Reference Tichenor2002). What is impressive is just how deep the effects still are today. In a political era, in which many claim that the significance of race has faded, Latino frames on immigration are linked to a macro shift in the political orientation of white Americans. Party identification—the most influential variable in American politics—responds, at least in part, to the way individual white Americans see immigration in the news. In short, who we are politically seems to be shaped substantially by concerns about immigration and racial change.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2016.25.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful for the comments and insights of Todd Knopp, Rene Rocha, Stella Rouse, Tom Wong, and the attendees at a 2013 PRIEC Conference at UC-Riverside. We are also thankful to Francisco Cantú, Michael Davidson, and Lydia Lundgren for their help in collecting the data. As always seems to be the case, all errors remain our own.