1. Introduction

Vertical convection, in which a layer of fluid is confined between two vertical plates maintained at different temperatures, is relevant for industrial applications, including the control of insulation properties of double-glazed windows. Vertical convection also serves as a model system in the geophysical context to describe convectively driven flows in the Earth, the ocean and the atmosphere. Moreover, vertical convection is a fundamental hydrodynamics problem in its own right, as a prototype for studying pattern formation mechanisms within spatially extended driven dissipative nonlinear out-of-equilibrium systems. In our companion paper Zheng, Tuckerman & Schneider (Reference Zheng, Tuckerman and Schneider2024), we studied a domain in which the transverse (or spanwise) direction was taken to be of the same length as the distance between the plates (the wall-normal direction), with the vertical dimension (parallel to gravity) chosen large compared with both. Consequently, flow patterns are primarily two-dimensional (2-D), with variations predominantly in the vertical and wall-normal direction. Here, we will consider an extended three-dimensional (3-D) geometry, in which the transverse and vertical dimensions are both large compared with the inter-plate spacing and, thus, flow patterns vary in two extended directions.

We begin by briefly surveying 3-D numerical investigations of vertical convection. Chait & Korpela (Reference Chait and Korpela1989), Henry & Buffat (Reference Henry and Buffat1998) and Xin & Le Quéré (Reference Xin and Le Quéré2002) analysed the instability of 2-D nonlinear flow (transverse rolls) to 3-D perturbations in order to determine when and whether the flow could be assumed to be 2-D. In Rayleigh–Bénard convection, the stability thresholds in Rayleigh number (![]() $Ra$), Prandtl number (

$Ra$), Prandtl number (![]() $Pr$) and 2-D roll wavelength delimit a volume that is called the Busse balloon (Busse Reference Busse1978), named after the researcher who has been at the forefront of pattern formation research in Rayleigh–Bénard convection. Busse later also transferred his analysis to vertical convection. Using the approximation (corresponding to infinite thermal diffusivity) that the temperature retains its linear conductive profile, Nagata & Busse (Reference Nagata and Busse1983) computed a fully nonlinear 3-D solution which is probably the diamond roll state (FP2) to be described in § 3. Such 3-D solutions have sometimes been termed tertiary solutions, whereas the laminar and 2-D transverse roll solutions are called primary and secondary, respectively. Clever & Busse (Reference Clever and Busse1995) extended the computation of 3-D solutions to

$Pr$) and 2-D roll wavelength delimit a volume that is called the Busse balloon (Busse Reference Busse1978), named after the researcher who has been at the forefront of pattern formation research in Rayleigh–Bénard convection. Busse later also transferred his analysis to vertical convection. Using the approximation (corresponding to infinite thermal diffusivity) that the temperature retains its linear conductive profile, Nagata & Busse (Reference Nagata and Busse1983) computed a fully nonlinear 3-D solution which is probably the diamond roll state (FP2) to be described in § 3. Such 3-D solutions have sometimes been termed tertiary solutions, whereas the laminar and 2-D transverse roll solutions are called primary and secondary, respectively. Clever & Busse (Reference Clever and Busse1995) extended the computation of 3-D solutions to ![]() $Pr=0.71$, corresponding to convection in air, the case we study in this paper.

$Pr=0.71$, corresponding to convection in air, the case we study in this paper.

Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Sergent, Podvin, Xin, Le Quéré and Tuckerman2013, Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent and Xin2015, Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018) combined linear and weakly nonlinear theory as well as direct numerical simulations (DNS) to study the 3-D flow. Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Sergent, Podvin, Xin, Le Quéré and Tuckerman2013, Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent and Xin2015) studied the equilibria and periodic orbits in a computational domain of size ![]() $[L_x, L_y, L_z] = [1, 1, 10]$, the same domain we consider in our companion paper Zheng et al. (Reference Zheng, Tuckerman and Schneider2024). In order to study secondary instabilities in the transverse direction of the 2-D steady rolls, Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018) computed their linear stability. Their analysis showed two types of instabilities, with spanwise wavelengths of about four and eight. They consequently extended the spanwise length of the domain from unity to

$[L_x, L_y, L_z] = [1, 1, 10]$, the same domain we consider in our companion paper Zheng et al. (Reference Zheng, Tuckerman and Schneider2024). In order to study secondary instabilities in the transverse direction of the 2-D steady rolls, Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018) computed their linear stability. Their analysis showed two types of instabilities, with spanwise wavelengths of about four and eight. They consequently extended the spanwise length of the domain from unity to ![]() $L_y=8$ to capture both instabilities. In addition, when

$L_y=8$ to capture both instabilities. In addition, when ![]() $L_z=9$ the Rayleigh number thresholds of both types of 3-D instabilities are close, motivating them to decrease

$L_z=9$ the Rayleigh number thresholds of both types of 3-D instabilities are close, motivating them to decrease ![]() $L_z$ from

$L_z$ from ![]() $10$ to

$10$ to ![]() $9$ in order to study the competition between both instabilities destabilising 2-D rolls. Like a spanwise domain size of

$9$ in order to study the competition between both instabilities destabilising 2-D rolls. Like a spanwise domain size of ![]() $L_z=10$, a domain with

$L_z=10$, a domain with ![]() $L_z = 9$ also accommodates four co-rotating rolls in the primary instability of the base state and is large enough to allow interactions between rolls. Cimarelli & Angeli (Reference Cimarelli and Angeli2017) and Cingi, Cimarelli & Angeli (Reference Cingi, Cimarelli and Angeli2021) unsuccessfully attempted to explain the results of Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Sergent, Podvin, Xin, Le Quéré and Tuckerman2013, Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018) from a bifurcation-theoretic point of view.

$L_z = 9$ also accommodates four co-rotating rolls in the primary instability of the base state and is large enough to allow interactions between rolls. Cimarelli & Angeli (Reference Cimarelli and Angeli2017) and Cingi, Cimarelli & Angeli (Reference Cingi, Cimarelli and Angeli2021) unsuccessfully attempted to explain the results of Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Sergent, Podvin, Xin, Le Quéré and Tuckerman2013, Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018) from a bifurcation-theoretic point of view.

In this paper, we study vertical convection in air (![]() $Pr=0.71$) in the configuration

$Pr=0.71$) in the configuration ![]() $[L_x,L_y,L_z]=[1,8,9]$. Similarly to the approach described in Zheng et al. (Reference Zheng, Tuckerman and Schneider2024), we extend previous studies by Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018) that were based primarily on time-stepping by using numerical continuation and stability analysis. This unravels the bifurcation-theoretic origins of complex flows and the connections between them. This approach of explaining patterns and their dynamics in terms of equilibria and periodic orbits has been applied successfully to inclined layer convection where fascinating convection patterns were previously observed in DNS and experimentally by Daniels, Plapp & Bodenschatz (Reference Daniels, Plapp and Bodenschatz2000). Through a numerical bifurcation analysis, Reetz & Schneider (Reference Reetz and Schneider2020) and Reetz, Subramanian & Schneider (Reference Reetz, Subramanian and Schneider2020) identified the invariant solutions underlying most of the patterns and constructed bifurcation diagrams connecting them. These invariant solutions capture key features and dynamics of the observed patterns and the bifurcation diagrams reveal their origin. Here, we follow the same strategy to explain flow patterns in vertical convection in a somewhat larger domain.

$[L_x,L_y,L_z]=[1,8,9]$. Similarly to the approach described in Zheng et al. (Reference Zheng, Tuckerman and Schneider2024), we extend previous studies by Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018) that were based primarily on time-stepping by using numerical continuation and stability analysis. This unravels the bifurcation-theoretic origins of complex flows and the connections between them. This approach of explaining patterns and their dynamics in terms of equilibria and periodic orbits has been applied successfully to inclined layer convection where fascinating convection patterns were previously observed in DNS and experimentally by Daniels, Plapp & Bodenschatz (Reference Daniels, Plapp and Bodenschatz2000). Through a numerical bifurcation analysis, Reetz & Schneider (Reference Reetz and Schneider2020) and Reetz, Subramanian & Schneider (Reference Reetz, Subramanian and Schneider2020) identified the invariant solutions underlying most of the patterns and constructed bifurcation diagrams connecting them. These invariant solutions capture key features and dynamics of the observed patterns and the bifurcation diagrams reveal their origin. Here, we follow the same strategy to explain flow patterns in vertical convection in a somewhat larger domain.

Using parametric continuation techniques that can follow states irrespective of their stability, we describe the discovery of three new branches of steady states, which, together with those observed by Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018) via time integration, brings the number of branches observed thus far to six. Several of these new states bifurcate simultaneously, at the same value of the control parameter, despite not being related by symmetry. We have shown that this otherwise non-generic phenomenon is explained by the fact that the parent branches have ![]() $D_4$ symmetry; see Swift (Reference Swift1985), Knobloch (Reference Knobloch1986), Chossat & Iooss (Reference Chossat and Iooss1994), Bergeon, Henry & Knobloch (Reference Bergeon, Henry and Knobloch2001) and Reetz et al. (Reference Reetz, Subramanian and Schneider2020). In our geometry,

$D_4$ symmetry; see Swift (Reference Swift1985), Knobloch (Reference Knobloch1986), Chossat & Iooss (Reference Chossat and Iooss1994), Bergeon, Henry & Knobloch (Reference Bergeon, Henry and Knobloch2001) and Reetz et al. (Reference Reetz, Subramanian and Schneider2020). In our geometry, ![]() $D_4$ symmetry leads to simultaneous bifurcations to states that are aligned with respect to the transverse and vertical directions, and others which are diagonal with respect to them. Competition between aligned and diagonal states is also seen in two periodic orbits (observed by Gao et al. Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018), that consist of diagonal excursions from states which are more aligned. We have also discovered two new periodic orbits.

$D_4$ symmetry leads to simultaneous bifurcations to states that are aligned with respect to the transverse and vertical directions, and others which are diagonal with respect to them. Competition between aligned and diagonal states is also seen in two periodic orbits (observed by Gao et al. Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018), that consist of diagonal excursions from states which are more aligned. We have also discovered two new periodic orbits.

Most of the steady states and periodic orbits that we have identified are unstable. While these are not directly observed in time-dependent simulations, following unstable branches is essential for understanding the origin of stable states and for constructing a bifurcation diagram unifying the solutions to a problem. Moreover, unstable states play the role of way-stations, near which chaotic or turbulent trajectories spend much of their time. These are believed to form the core structures supporting weakly turbulent dynamics. Among the unstable periodic orbits that may influence trajectories of a fluid-dynamical system, we have discovered some whose branches terminate in global bifurcations, leading to their disappearance. Although there have been a number of computations of global bifurcations in hydrodynamic systems (Tuckerman & Barkley Reference Tuckerman and Barkley1988; Prat, Mercader & Knobloch Reference Prat, Mercader and Knobloch2002; Millour, Labrosse & Tric Reference Millour, Labrosse and Tric2003; Nore et al. Reference Nore, Tuckerman, Daube and Xin2003; Abshagen et al. Reference Abshagen, Lopez, Marques and Pfister2005; Bordja et al. Reference Bordja, Tuckerman, Witkowski, Navarro, Dwight and Bessaih2010; Bengana & Tuckerman Reference Bengana and Tuckerman2019; Reetz et al. Reference Reetz, Subramanian and Schneider2020), we are not aware of previous calculations of heteroclinic or homoclinic cycles in vertical convection.

The remainder of this article is organised as follows. In § 2 we summarise the key numerical methods used in our research which are already presented in detail in Zheng et al. (Reference Zheng, Tuckerman and Schneider2024). The results from the bifurcation analysis are presented in § 3 for fixed points and in § 4 for periodic orbits. Concluding remarks and future research directions are outlined in § 5.

2. System and methods

We refer the reader to Reetz (Reference Reetz2019), Reetz & Schneider (Reference Reetz and Schneider2020), Reetz et al. (Reference Reetz, Subramanian and Schneider2020), and Zheng et al. (Reference Zheng, Tuckerman and Schneider2024) for detailed descriptions of the numerical methods used in the research. Here, we only summarise the key points.

2.1. The DNS of vertical convection

The vertical convection system is studied numerically by performing DNS with the ILC extension module of the Channelflow 2.0 code (Gibson et al. Reference Gibson, Reetz, Azmi, Ferraro, Kreilos, Schrobsdorff, Farano, Yesil, Schütz and Culpo2021), to solve the non-dimensionalised Oberbeck–Boussinesq equations

$$\begin{gather} \dfrac{\partial \boldsymbol{u}}{\partial t} + (\boldsymbol{u}\boldsymbol{\cdot}\boldsymbol{\nabla})\boldsymbol{u} ={-}\boldsymbol{\nabla} p + \left(\frac{Pr}{Ra}\right)^{1/2} \nabla^2 \boldsymbol{u} + \mathcal{T}\boldsymbol e_z, \end{gather}$$

$$\begin{gather} \dfrac{\partial \boldsymbol{u}}{\partial t} + (\boldsymbol{u}\boldsymbol{\cdot}\boldsymbol{\nabla})\boldsymbol{u} ={-}\boldsymbol{\nabla} p + \left(\frac{Pr}{Ra}\right)^{1/2} \nabla^2 \boldsymbol{u} + \mathcal{T}\boldsymbol e_z, \end{gather}$$ $$\begin{gather}\dfrac{\partial \mathcal{T}}{\partial t} + (\boldsymbol{u} \boldsymbol{\cdot}\boldsymbol{\nabla})\mathcal{T} = \left(\frac{1}{Pr\,Ra}\right)^{1/2}\nabla^2 \mathcal{T}, \end{gather}$$

$$\begin{gather}\dfrac{\partial \mathcal{T}}{\partial t} + (\boldsymbol{u} \boldsymbol{\cdot}\boldsymbol{\nabla})\mathcal{T} = \left(\frac{1}{Pr\,Ra}\right)^{1/2}\nabla^2 \mathcal{T}, \end{gather}$$

in a vertical channel, with periodic boundary conditions in ![]() $y$ and

$y$ and ![]() $z$, shown in figure 1. The boundary conditions in

$z$, shown in figure 1. The boundary conditions in ![]() $x$ at the two walls are of Dirichlet type:

$x$ at the two walls are of Dirichlet type:

Supplementary integral constraints are necessary in the periodic directions; we set the mean pressure gradient to zero in both ![]() $y$ and

$y$ and ![]() $z$. The laminar solution, illustrated in figure 1, is

$z$. The laminar solution, illustrated in figure 1, is

with arbitrary pressure constant ![]() $\varPi$.

$\varPi$.

Figure 1. Schematic of the vertical convection configuration approximating ![]() $[L_x, L_y, L_z] = [1, 8, 9]$. The flow is bounded between two walls in

$[L_x, L_y, L_z] = [1, 8, 9]$. The flow is bounded between two walls in ![]() $x$ direction at

$x$ direction at ![]() $x=0.5$ where the flow is heated and at

$x=0.5$ where the flow is heated and at ![]() $x=-0.5$ where the flow is cooled. The domain is periodic in

$x=-0.5$ where the flow is cooled. The domain is periodic in ![]() $y$ and

$y$ and ![]() $z$ directions. Most of the visualisations that we present are taken on the

$z$ directions. Most of the visualisations that we present are taken on the ![]() $y$–

$y$–![]() $z$ midplane at

$z$ midplane at ![]() $x=0$ outlined by the dotted lines, and they are visualised in the direction of negative to positive

$x=0$ outlined by the dotted lines, and they are visualised in the direction of negative to positive ![]() $x$, as indicated by the eye and arrow. The laminar velocity and temperature are shown as the orange and green curves, respectively.

$x$, as indicated by the eye and arrow. The laminar velocity and temperature are shown as the orange and green curves, respectively.

The governing equations and boundary conditions are discussed in our companion paper Zheng et al. (Reference Zheng, Tuckerman and Schneider2024). The only aspect which differs here is the domain size: instead of the narrow domain ![]() $[L_x, L_y, L_z] = [1, 1, 10]$ with one extended direction studied in Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Sergent, Podvin, Xin, Le Quéré and Tuckerman2013), here we study the 3-D computational domain

$[L_x, L_y, L_z] = [1, 1, 10]$ with one extended direction studied in Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Sergent, Podvin, Xin, Le Quéré and Tuckerman2013), here we study the 3-D computational domain ![]() $[L_x, L_y, L_z] = [1, 8, 9]$ of Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018). This domain has two extended directions and is illustrated in figure 1. This domain is spatially discretised by

$[L_x, L_y, L_z] = [1, 8, 9]$ of Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018). This domain has two extended directions and is illustrated in figure 1. This domain is spatially discretised by ![]() $[N_x, N_y, N_z] = [31, 96, 96]$ Chebychev–Fourier–Fourier modes.

$[N_x, N_y, N_z] = [31, 96, 96]$ Chebychev–Fourier–Fourier modes.

2.2. Symmetries and computation of invariant solutions

We often refer to the symmetries of our system, the group ![]() $S_{VC}$, which is generated by reflection in

$S_{VC}$, which is generated by reflection in ![]() $y$, combined reflection of

$y$, combined reflection of ![]() $x$,

$x$, ![]() $z$ and temperature

$z$ and temperature ![]() $\mathcal {T}$, and translation in

$\mathcal {T}$, and translation in ![]() $y$ and

$y$ and ![]() $z$:

$z$:

stated more compactly as ![]() $S_{VC} \equiv \langle {{\rm \pi} _y, {\rm \pi}_{xz}, \tau (\Delta y, \Delta z)} \rangle \sim [O(2)]_y \times [O(2)]_{x,z}$. The groups we use are

$S_{VC} \equiv \langle {{\rm \pi} _y, {\rm \pi}_{xz}, \tau (\Delta y, \Delta z)} \rangle \sim [O(2)]_y \times [O(2)]_{x,z}$. The groups we use are ![]() $Z_n$, the cyclic group of

$Z_n$, the cyclic group of ![]() $n$ elements,

$n$ elements, ![]() $D_n$, the cyclic group of

$D_n$, the cyclic group of ![]() $n$ elements together with a non-commuting reflection, and

$n$ elements together with a non-commuting reflection, and ![]() $O(2)$, the group of all rotations together with a non-commuting reflection. Here

$O(2)$, the group of all rotations together with a non-commuting reflection. Here ![]() $[O(2)]_y$ refers to reflections and translations in

$[O(2)]_y$ refers to reflections and translations in ![]() $y$, as in (2.4a) and (2.4c), respectively, whereas

$y$, as in (2.4a) and (2.4c), respectively, whereas ![]() $[O(2)]_{xz}$ refers to reflections in

$[O(2)]_{xz}$ refers to reflections in ![]() $(\mathcal {T},x,z)$ as in (2.4b) and translations in

$(\mathcal {T},x,z)$ as in (2.4b) and translations in ![]() $z$ as in (2.4c), a convention that we use in the rest of the paper where possible. Note that the generators of a group are non-unique, as is the decomposition into direct products (indicated by

$z$ as in (2.4c), a convention that we use in the rest of the paper where possible. Note that the generators of a group are non-unique, as is the decomposition into direct products (indicated by ![]() $\times$).

$\times$).

We adopt the shooting-based matrix-free Newton method implemented in Channelflow 2.0 to compute invariant solutions. The only difference with respect to our description in Zheng et al. (Reference Zheng, Tuckerman and Schneider2024) arises from the presence here of homoclinic and heteroclinic orbits. Although the Newton method can converge with one shot in most of the cases (provided that the initial guess is sufficiently close to the solution), the multi-shooting method (Sánchez & Net Reference Sánchez and Net2010; van Veen, Kawahara & Atsushi Reference van Veen, Kawahara and Atsushi2011) is required in order to converge orbits with long periods (typically ![]() $T > 300$ in our case) that are close to a global bifurcation point and very unstable orbits. For these periodic orbits, we employ the multi-shooting method with at most six shots.

$T > 300$ in our case) that are close to a global bifurcation point and very unstable orbits. For these periodic orbits, we employ the multi-shooting method with at most six shots.

To characterise the stability of a solution, its leading eigenvalues and eigenvectors for fixed points, or Floquet exponents and Floquet modes for periodic orbits, are determined by Arnoldi iterations. When solutions have symmetries, the resulting linear stability problem has the same symmetries, leading to multiple eigenvectors sharing the same eigenvalues. In such cases, we choose the eigenvectors appropriate to our analysis either by subtracting two nonlinear flow fields along a trajectory or branch, or by imposing symmetries.

2.3. Order parameter and flow visualisation

Once an equilibrium or time-periodic solution is converged, parametric continuation in Rayleigh number is performed to construct bifurcation diagrams. Solutions are represented via the ![]() $L_2$-norm of their temperature deviation

$L_2$-norm of their temperature deviation ![]() $\theta \equiv \mathcal {T} - \mathcal {T}_0$. Branches of fixed points are represented by curves showing

$\theta \equiv \mathcal {T} - \mathcal {T}_0$. Branches of fixed points are represented by curves showing ![]() $\lvert \lvert \theta \lvert \lvert _2$ as a function of

$\lvert \lvert \theta \lvert \lvert _2$ as a function of ![]() $Ra$; for periodic orbits, the maximum and minimum of

$Ra$; for periodic orbits, the maximum and minimum of ![]() $\lvert \lvert \theta \lvert \lvert _2$ along an orbit are plotted. The flows are visualized via their temperature deviation fields

$\lvert \lvert \theta \lvert \lvert _2$ along an orbit are plotted. The flows are visualized via their temperature deviation fields ![]() $\theta$ on the y–z plane at

$\theta$ on the y–z plane at ![]() $x=0$ and on the x–z plane at

$x=0$ and on the x–z plane at ![]() $y=4$. The thermal energy input

$y=4$. The thermal energy input ![]() $I$ due to buoyancy and the dissipation

$I$ due to buoyancy and the dissipation ![]() $D$ due to viscosity are used to plot phase portraits.

$D$ due to viscosity are used to plot phase portraits.

3. Fixed points

We begin by noting that the numbering used for fixed points and for periodic orbits applies only to this paper; except for FP1, the fixed points and periodic orbits here are not the same as those in Zheng et al. (Reference Zheng, Tuckerman and Schneider2024).

3.1. Three known fixed points: FP1–FP3

Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018) observed three fixed points in the domain ![]() $[L_x, L_y, L_z] = [1, 8, 9]$ and presented visualisations and Fourier decompositions of them. These states have been recomputed here and their flow structures are shown in figures 2(b)–2(d). In this work, we identify the bifurcations that create and destroy these states and construct a bifurcation diagram that includes stable and unstable branches. As presented in the bifurcation diagram in figure 2(a), the laminar base flow is stable until

$[L_x, L_y, L_z] = [1, 8, 9]$ and presented visualisations and Fourier decompositions of them. These states have been recomputed here and their flow structures are shown in figures 2(b)–2(d). In this work, we identify the bifurcations that create and destroy these states and construct a bifurcation diagram that includes stable and unstable branches. As presented in the bifurcation diagram in figure 2(a), the laminar base flow is stable until ![]() $Ra=5707$, where the first fixed point, FP1, bifurcates. As in Zheng et al. (Reference Zheng, Tuckerman and Schneider2024), FP1 is called 2-D or transverse rolls. This state contains four spanwise (

$Ra=5707$, where the first fixed point, FP1, bifurcates. As in Zheng et al. (Reference Zheng, Tuckerman and Schneider2024), FP1 is called 2-D or transverse rolls. This state contains four spanwise (![]() $y$)-independent co-rotating convection rolls, and is shown in figures 2(b) and 3(a). Cingi et al. (Reference Cingi, Cimarelli and Angeli2021) have reported bistability between the base flow and 2-D rolls in several Rayleigh-number ranges, but their interpretation contradicts the results obtained here and also those reported by Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018). In particular, Cingi et al. (Reference Cingi, Cimarelli and Angeli2021) find the laminar flow to be bistable with 2-D rolls (FP1) over the Rayleigh number range of

$y$)-independent co-rotating convection rolls, and is shown in figures 2(b) and 3(a). Cingi et al. (Reference Cingi, Cimarelli and Angeli2021) have reported bistability between the base flow and 2-D rolls in several Rayleigh-number ranges, but their interpretation contradicts the results obtained here and also those reported by Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018). In particular, Cingi et al. (Reference Cingi, Cimarelli and Angeli2021) find the laminar flow to be bistable with 2-D rolls (FP1) over the Rayleigh number range of ![]() $[5708, 7000]$. We believe this reported bistability to be spurious, and to almost certainly result from the use by Cingi et al. (Reference Cingi, Cimarelli and Angeli2021) of a time-stepping code to simulate a weakly unstable state without monitoring the growth or decay of perturbations nor a complementary linear stability analysis.

$[5708, 7000]$. We believe this reported bistability to be spurious, and to almost certainly result from the use by Cingi et al. (Reference Cingi, Cimarelli and Angeli2021) of a time-stepping code to simulate a weakly unstable state without monitoring the growth or decay of perturbations nor a complementary linear stability analysis.

Figure 2. Bifurcation diagram (a) and flow structures visualised via the temperature field on the ![]() $y$–

$y$–![]() $z$ plane at

$z$ plane at ![]() $x=0$ (b–g) of six equilibria in domain

$x=0$ (b–g) of six equilibria in domain ![]() $[L_x, L_y, L_z] = [1, 8, 9]$. The diagram shows two supercritical pitchfork bifurcations, one from the base state to FP1 (b) and another one from FP1 to FP2 (c). Fixed point FP3 (d) bifurcates from FP2 in a subcritical pitchfork bifurcation. The unstable FP4 (e) bifurcates supercritically from FP1. The unstable FP5 branch (f) bifurcates at one end subcritically from FP2, and at the another end supercritically from FP1. FP3 and FP5 bifurcate together from FP2, whereas FP4 and FP5 bifurcate together from FP1. Two small grey rectangles surround these two simultaneous bifurcations, which are also shown in the enlarged diagrams on the right. On the lower enlarged diagram, the dashed red and brown lines are distinct, but too close to one another to be distinguished. FP6 bifurcates from FP5 in two supercritical pitchfork bifurcations and it connects FP5 at two Rayleigh numbers. In (a), solid and dashed curves signify stable and unstable states, respectively. The ranges over which FP1, FP2, FP3 and FP6 are stable are

$[L_x, L_y, L_z] = [1, 8, 9]$. The diagram shows two supercritical pitchfork bifurcations, one from the base state to FP1 (b) and another one from FP1 to FP2 (c). Fixed point FP3 (d) bifurcates from FP2 in a subcritical pitchfork bifurcation. The unstable FP4 (e) bifurcates supercritically from FP1. The unstable FP5 branch (f) bifurcates at one end subcritically from FP2, and at the another end supercritically from FP1. FP3 and FP5 bifurcate together from FP2, whereas FP4 and FP5 bifurcate together from FP1. Two small grey rectangles surround these two simultaneous bifurcations, which are also shown in the enlarged diagrams on the right. On the lower enlarged diagram, the dashed red and brown lines are distinct, but too close to one another to be distinguished. FP6 bifurcates from FP5 in two supercritical pitchfork bifurcations and it connects FP5 at two Rayleigh numbers. In (a), solid and dashed curves signify stable and unstable states, respectively. The ranges over which FP1, FP2, FP3 and FP6 are stable are ![]() $[5707, 6056]$,

$[5707, 6056]$, ![]() $[6056, 6058.5]$,

$[6056, 6058.5]$, ![]() $[6008.5, 6140]$ and

$[6008.5, 6140]$ and ![]() $[6251.4, 6257.6]$, respectively. The stars in (a) indicate the locations of the visualisations of (b–g). Fixed points FP1–FP3 are discussed in Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018) whereas FP4–FP6 are newly identified in this work. Other branches of equilibria exist, which we have not followed nor shown on this diagram. Flow visualisations on the

$[6251.4, 6257.6]$, respectively. The stars in (a) indicate the locations of the visualisations of (b–g). Fixed points FP1–FP3 are discussed in Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018) whereas FP4–FP6 are newly identified in this work. Other branches of equilibria exist, which we have not followed nor shown on this diagram. Flow visualisations on the ![]() $x$–

$x$–![]() $z$ plane are shown in figure 3.

$z$ plane are shown in figure 3.

Fixed point FP1 loses stability at ![]() $Ra = 6056$ via a circle pitchfork bifurcation that breaks the

$Ra = 6056$ via a circle pitchfork bifurcation that breaks the ![]() $y$ translation symmetry

$y$ translation symmetry ![]() $\tau (\Delta y,0)$ and creates FP2, shown in figures 2(c) and 3(b). We refer to these as diamond rolls, whereas Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018) called them wavy rolls. Fixed point FP2 results from the subharmonic varicose instability of FP1, which was discussed in Subramanian et al. (Reference Subramanian, Brausch, Daniels, Bodenschatz, Schneider and Pesch2016) and Reetz et al. (Reference Reetz, Subramanian and Schneider2020). FP2 undergoes subcritical pitchfork bifurcations at

$\tau (\Delta y,0)$ and creates FP2, shown in figures 2(c) and 3(b). We refer to these as diamond rolls, whereas Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018) called them wavy rolls. Fixed point FP2 results from the subharmonic varicose instability of FP1, which was discussed in Subramanian et al. (Reference Subramanian, Brausch, Daniels, Bodenschatz, Schneider and Pesch2016) and Reetz et al. (Reference Reetz, Subramanian and Schneider2020). FP2 undergoes subcritical pitchfork bifurcations at ![]() $Ra = 6058.5$, so that its stability range is only

$Ra = 6058.5$, so that its stability range is only ![]() $[6056,6058.5]$. The time-dependent simulations of Cingi et al. (Reference Cingi, Cimarelli and Angeli2021) did not detect FP2. In contrast, Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018) observed FP2 as a transient at

$[6056,6058.5]$. The time-dependent simulations of Cingi et al. (Reference Cingi, Cimarelli and Angeli2021) did not detect FP2. In contrast, Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018) observed FP2 as a transient at ![]() $Ra=6100$ and computed its threshold via a linear stability analysis. Clever & Busse (Reference Clever and Busse1995) computed a state resembling FP2 by means of a steady-state calculation. (Their threshold of about

$Ra=6100$ and computed its threshold via a linear stability analysis. Clever & Busse (Reference Clever and Busse1995) computed a state resembling FP2 by means of a steady-state calculation. (Their threshold of about ![]() $Ra\approx 6295$ can perhaps be attributed to a lack of spatial resolution available in 1995.)

$Ra\approx 6295$ can perhaps be attributed to a lack of spatial resolution available in 1995.)

The bifurcation from FP2 creates FP3, which Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018) call thinning rolls. Initially unstable, FP3 is stabilised by a saddle-node bifurcation at ![]() $Ra = 6008.5$. At higher Rayleigh number, FP3 undergoes two additional saddle-node bifurcations at

$Ra = 6008.5$. At higher Rayleigh number, FP3 undergoes two additional saddle-node bifurcations at ![]() $Ra=6265.8$ and

$Ra=6265.8$ and ![]() $Ra=6209.56$. As pointed out by Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018), FP3 can have either of two possible diagonal orientations. Figure 2(d) shows one of the two cases: the slightly wider red portions are located along a diagonal joining the top left with the bottom right.

$Ra=6209.56$. As pointed out by Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Podvin, Sergent, Xin and Chergui2018), FP3 can have either of two possible diagonal orientations. Figure 2(d) shows one of the two cases: the slightly wider red portions are located along a diagonal joining the top left with the bottom right.

The symmetry (isotropy) groups of FP1–FP3 are

\begin{equation}

\left.\begin{gathered}

\text{FP1:} \ \langle{{\rm \pi}_y, \tau(\Delta y,0),{\rm \pi}_{xz},\tau(0,L_z/4)} \rangle \sim [O(2)]_y \times [D_4]_{xz};\\

\text{FP2:} \ \langle{{\rm \pi}_y, \tau(L_y/2,0), {\rm \pi}_{xz}, \tau(0, L_z/2), \tau(L_y/4, -L_z/4)} \rangle \sim D_2 \times D_4; \\

\text{FP3:} \ \langle{{\rm \pi}_y{\rm \pi}_{xz}, \tau(L_y/4,-L_z/4)} \rangle \sim D_4. \end{gathered}\right\}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\left.\begin{gathered}

\text{FP1:} \ \langle{{\rm \pi}_y, \tau(\Delta y,0),{\rm \pi}_{xz},\tau(0,L_z/4)} \rangle \sim [O(2)]_y \times [D_4]_{xz};\\

\text{FP2:} \ \langle{{\rm \pi}_y, \tau(L_y/2,0), {\rm \pi}_{xz}, \tau(0, L_z/2), \tau(L_y/4, -L_z/4)} \rangle \sim D_2 \times D_4; \\

\text{FP3:} \ \langle{{\rm \pi}_y{\rm \pi}_{xz}, \tau(L_y/4,-L_z/4)} \rangle \sim D_4. \end{gathered}\right\}

\end{equation}

Note that ![]() $\tau (L_y/4,-L_z/4)=\tau (L_y/4,3L_z/4)$, and that the symmetry groups for FP2 and FP3 cannot be divided into those related to

$\tau (L_y/4,-L_z/4)=\tau (L_y/4,3L_z/4)$, and that the symmetry groups for FP2 and FP3 cannot be divided into those related to ![]() $y$ and those related to

$y$ and those related to ![]() $x,z$. The bifurcation from

$x,z$. The bifurcation from ![]() $\textrm {FP}2\rightarrow \textrm {FP}3$ breaks the

$\textrm {FP}2\rightarrow \textrm {FP}3$ breaks the ![]() $D_4$ symmetry of FP2.

$D_4$ symmetry of FP2.

3.2. Three new fixed points: FP4–FP6

We have also found three new branches of fixed points, FP4–FP6. Figure 2(a) shows that there is a supercritical pitchfork bifurcation at ![]() $Ra=6131$, at which FP4 and FP5 bifurcate simultaneously from FP1. Both FP4 and FP5 are unstable along their entire branches. (The enlarged diagram on the bottom right of figure 2(a) contains two distinct dashed red and brown lines which are too close to be distinguished.) Since FP1 is

$Ra=6131$, at which FP4 and FP5 bifurcate simultaneously from FP1. Both FP4 and FP5 are unstable along their entire branches. (The enlarged diagram on the bottom right of figure 2(a) contains two distinct dashed red and brown lines which are too close to be distinguished.) Since FP1 is ![]() $y$-independent and FP4 and FP5 are not, these are circle pitchfork bifurcations, yielding FP4 and FP5 states of any phase in

$y$-independent and FP4 and FP5 are not, these are circle pitchfork bifurcations, yielding FP4 and FP5 states of any phase in ![]() $y$. Fixed point FP4, shown in figures 2(e) and 3(d), shares with FP3 a diagonal orientation. Fixed point FP4 also consists of rolls with a slight wavy modulation along the

$y$. Fixed point FP4, shown in figures 2(e) and 3(d), shares with FP3 a diagonal orientation. Fixed point FP4 also consists of rolls with a slight wavy modulation along the ![]() $y$ direction, but this modulation is weaker than that of FP3. FP4 plays an essential role in one of the global bifurcations that we discuss in § 4.1.2.

$y$ direction, but this modulation is weaker than that of FP3. FP4 plays an essential role in one of the global bifurcations that we discuss in § 4.1.2.

The FP5 branch (which we refer to occasionally as the moustache branch) is shown in figures 2(f) and 3(e). After bifurcating from FP1, the FP5 branch undergoes saddle-node bifurcations at ![]() $Ra=6317.5$ and

$Ra=6317.5$ and ![]() $Ra= 6034$, towards decreasing and increasing Rayleigh number, respectively, and finally terminates at

$Ra= 6034$, towards decreasing and increasing Rayleigh number, respectively, and finally terminates at ![]() $Ra=6058.5$ by meeting FP2 in a subcritical pitchfork bifurcation. This is not a circle pitchfork bifurcation, since the diamond branch FP2 is also

$Ra=6058.5$ by meeting FP2 in a subcritical pitchfork bifurcation. This is not a circle pitchfork bifurcation, since the diamond branch FP2 is also ![]() $y$-dependent; four possible FP5 branches emanate from FP2, related to one another by translations in

$y$-dependent; four possible FP5 branches emanate from FP2, related to one another by translations in ![]() $y$ and in

$y$ and in ![]() $z$. (Fixed point FP3 is also created at

$z$. (Fixed point FP3 is also created at ![]() $Ra=6058.5$, in another simultaneous bifurcation that is discussed in § 3.3.) Thus, two routes connect FP1 to FP5: one route is a single circle pitchfork bifurcation and a second route is a circle pitchfork bifurcation from FP1 to FP2 followed by an ordinary pitchfork bifurcation from FP2 to FP5. The bifurcation from FP1 to FP2 breaks

$Ra=6058.5$, in another simultaneous bifurcation that is discussed in § 3.3.) Thus, two routes connect FP1 to FP5: one route is a single circle pitchfork bifurcation and a second route is a circle pitchfork bifurcation from FP1 to FP2 followed by an ordinary pitchfork bifurcation from FP2 to FP5. The bifurcation from FP1 to FP2 breaks ![]() $y$ invariance whereas that from FP2 to FP5 breaks the fourfold translation symmetry

$y$ invariance whereas that from FP2 to FP5 breaks the fourfold translation symmetry ![]() $\tau (L_y/4,-L_z/4)$.

$\tau (L_y/4,-L_z/4)$.

The last new equilibrium, FP6, shown in figures 2(g) and 3(f), is created from FP5 at ![]() $Ra=6164.3$ in a supercritical pitchfork bifurcation, inheriting the instability of FP5 at the bifurcation point. Fixed point FP6 becomes stable, but only over a very short range

$Ra=6164.3$ in a supercritical pitchfork bifurcation, inheriting the instability of FP5 at the bifurcation point. Fixed point FP6 becomes stable, but only over a very short range ![]() $Ra \in [6251.4,6257.6]$, indicated by the slight thickening of the branch in figure 2(a). (We do not discuss or show in figure 2(a) the new branches that necessarily emanate from the stabilising bifurcation at

$Ra \in [6251.4,6257.6]$, indicated by the slight thickening of the branch in figure 2(a). (We do not discuss or show in figure 2(a) the new branches that necessarily emanate from the stabilising bifurcation at ![]() $Ra=6251.4$, nor the numerous other branches created at points at which the real part of an eigenvalue crosses zero. The bifurcation at

$Ra=6251.4$, nor the numerous other branches created at points at which the real part of an eigenvalue crosses zero. The bifurcation at ![]() $Ra=6257.6$ is discussed in § 4.4.) FP6 then undergoes a saddle-node bifurcation at

$Ra=6257.6$ is discussed in § 4.4.) FP6 then undergoes a saddle-node bifurcation at ![]() $Ra=6329$ before terminating at the FP5 branch at

$Ra=6329$ before terminating at the FP5 branch at ![]() $Ra=6305.8$ in another supercritical pitchfork bifurcation.

$Ra=6305.8$ in another supercritical pitchfork bifurcation.

The symmetry groups of these states are

\begin{equation}

\left.\begin{gathered}

\text{FP4:} \ \langle{{\rm \pi}_y{\rm \pi}_{xz}, \tau(L_y/4,-L_z/4)} \rangle \sim D_4; \\

\text{FP5:} \ \langle{{\rm \pi}_y,{\rm \pi}_{xz}, \tau(L_y/2, L_z/2)} \rangle \sim [Z_2]_y \times [Z_2]_{xz} \times Z_2; \\

\text{FP6:} \ \langle{{\rm \pi}_y,{\rm \pi}_{xz}\tau(L_y/2,0)} \rangle \sim [Z_2]_y\times Z_2. \end{gathered}\right\}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\left.\begin{gathered}

\text{FP4:} \ \langle{{\rm \pi}_y{\rm \pi}_{xz}, \tau(L_y/4,-L_z/4)} \rangle \sim D_4; \\

\text{FP5:} \ \langle{{\rm \pi}_y,{\rm \pi}_{xz}, \tau(L_y/2, L_z/2)} \rangle \sim [Z_2]_y \times [Z_2]_{xz} \times Z_2; \\

\text{FP6:} \ \langle{{\rm \pi}_y,{\rm \pi}_{xz}\tau(L_y/2,0)} \rangle \sim [Z_2]_y\times Z_2. \end{gathered}\right\}

\end{equation}

Fixed point FP1 is homogeneous in ![]() $y$ and the states which branch from it, directly or indirectly, are FP2 with a

$y$ and the states which branch from it, directly or indirectly, are FP2 with a ![]() $y$ periodicity of

$y$ periodicity of ![]() $L_y/2=4$, and FP3, FP4, FP5 and FP6 with

$L_y/2=4$, and FP3, FP4, FP5 and FP6 with ![]() $y$-periodicity

$y$-periodicity ![]() $L_y=8$. This sets the stage for 1:2 mode interaction, as analysed in detail by Armbruster, Guckenheimer & Holmes (Reference Armbruster, Guckenheimer and Holmes1988), one of whose consequences is a robust heteroclinic cycle to be discussed in § 4.2.3.

$L_y=8$. This sets the stage for 1:2 mode interaction, as analysed in detail by Armbruster, Guckenheimer & Holmes (Reference Armbruster, Guckenheimer and Holmes1988), one of whose consequences is a robust heteroclinic cycle to be discussed in § 4.2.3.

3.3. Two simultaneous bifurcations

The two enlarged bifurcation diagrams on the right of figure 2(a) depict bifurcations at which two qualitatively different branches with different symmetries are created simultaneously. Fixed points FP3 and FP5 bifurcate simultaneously from FP2 at ![]() $Ra=6058.5$, and FP4 and FP5 bifurcate simultaneously from FP1 at

$Ra=6058.5$, and FP4 and FP5 bifurcate simultaneously from FP1 at ![]() $Ra= 6131$. These simultaneous bifurcations can be explained by the same

$Ra= 6131$. These simultaneous bifurcations can be explained by the same ![]() $D_4$ scenario that is discussed in detail in Zheng et al. (Reference Zheng, Tuckerman and Schneider2024). We repeat here the normal form corresponding to bifurcation in the presence of

$D_4$ scenario that is discussed in detail in Zheng et al. (Reference Zheng, Tuckerman and Schneider2024). We repeat here the normal form corresponding to bifurcation in the presence of ![]() $D_4$ symmetry:

$D_4$ symmetry:

The dynamical system (3.3) has the non-trivial solutions

i.e. two classes of solutions, (3.4a)–(3.4b), which we call here the diagonal solutions, and (3.4c)–(3.4d), which we call here the rectangular solutions, for reasons which figure 4 makes clear. The diagonal solutions are related to one another by symmetry, as are the rectangular ones, but the diagonal solutions are not related by symmetry to the rectangular solutions.

Figure 4. (a) Eigenvector ![]() $e_1$ responsible for

$e_1$ responsible for ![]() $\textrm {FP}2\rightarrow \textrm {FP}3$ bifurcation (obtained by subtracting FP2 at

$\textrm {FP}2\rightarrow \textrm {FP}3$ bifurcation (obtained by subtracting FP2 at ![]() $Ra=6058.5$ from FP3 at

$Ra=6058.5$ from FP3 at ![]() $Ra=6056$) and (b) its

$Ra=6056$) and (b) its ![]() $y$-reflected version

$y$-reflected version ![]() ${\rm \pi} _y e_1$. (c,d) Superpositions

${\rm \pi} _y e_1$. (c,d) Superpositions ![]() $(e_1 \pm {\rm \pi}_y e_1)/\sqrt {2}$. (e) Eigenvector

$(e_1 \pm {\rm \pi}_y e_1)/\sqrt {2}$. (e) Eigenvector ![]() $e_2$ responsible for

$e_2$ responsible for ![]() $\textrm {FP}2\rightarrow \textrm {FP}5$ bifurcation (obtained by subtracting FP2 at

$\textrm {FP}2\rightarrow \textrm {FP}5$ bifurcation (obtained by subtracting FP2 at ![]() $Ra=6058.5$ from FP5 at

$Ra=6058.5$ from FP5 at ![]() $Ra=6056$) and (f) its quarter-diagonal translation

$Ra=6056$) and (f) its quarter-diagonal translation ![]() $\tau (L_y/4,-L_z/4) e_2$. (g,h) Superpositions

$\tau (L_y/4,-L_z/4) e_2$. (g,h) Superpositions ![]() $(e_2 \pm \tau (L_y/4,-L_z/4) e_2)/\sqrt {2}$. All eigenvectors are visualised via the temperature field on the

$(e_2 \pm \tau (L_y/4,-L_z/4) e_2)/\sqrt {2}$. All eigenvectors are visualised via the temperature field on the ![]() $y$–

$y$–![]() $z$ plane at

$z$ plane at ![]() $x=0$. The same colour bar is used in all plots.

$x=0$. The same colour bar is used in all plots.

We begin by explaining the simultaneous bifurcation from FP2. The symmetry group ![]() $D_4$ of FP2 is generated by the translation operator

$D_4$ of FP2 is generated by the translation operator ![]() $\tau (L_y/4, -L_z/4)$ together with either of the reflection operators,

$\tau (L_y/4, -L_z/4)$ together with either of the reflection operators, ![]() ${\rm \pi} _y$ or

${\rm \pi} _y$ or ![]() ${\rm \pi} _{xz}$. Fixed point FP2 is invariant under any product of these operations. In the model (3.3), FP2 corresponds to the trivial solution

${\rm \pi} _{xz}$. Fixed point FP2 is invariant under any product of these operations. In the model (3.3), FP2 corresponds to the trivial solution ![]() $p=q=0$ from which the other solutions bifurcate.

$p=q=0$ from which the other solutions bifurcate.

When FP2 loses stability at ![]() $Ra=6058.5$, a real eigenvalue

$Ra=6058.5$, a real eigenvalue ![]() $\lambda _{1,2}$ crosses the imaginary axis. This double eigenvalue has a 2-D eigenspace, spanned by any two of its linearly independent eigenvectors. Figure 4(a) shows the eigenvector

$\lambda _{1,2}$ crosses the imaginary axis. This double eigenvalue has a 2-D eigenspace, spanned by any two of its linearly independent eigenvectors. Figure 4(a) shows the eigenvector ![]() $e_1$ of FP2 giving rise to state FP3 shown in figure 2(d), whereas figure 4(b) shows its

$e_1$ of FP2 giving rise to state FP3 shown in figure 2(d), whereas figure 4(b) shows its ![]() $y$-reflection,

$y$-reflection, ![]() ${\rm \pi} _y e_1$. Since

${\rm \pi} _y e_1$. Since ![]() ${\rm \pi} _y$ belongs to the symmetry group of FP2,

${\rm \pi} _y$ belongs to the symmetry group of FP2, ![]() ${\rm \pi} _y e_1$ is also an eigenvector of FP2, as is any superposition of

${\rm \pi} _y e_1$ is also an eigenvector of FP2, as is any superposition of ![]() $e_1$ and

$e_1$ and ![]() ${\rm \pi} _y e_1$. The diagonal solution (3.4a) represents FP3 which arises from eigenvector

${\rm \pi} _y e_1$. The diagonal solution (3.4a) represents FP3 which arises from eigenvector ![]() $e_1$. Solution (3.4b) represents FP3

$e_1$. Solution (3.4b) represents FP3![]() $^\prime \equiv {\rm \pi}_y$FP3, whose diagonal is reversed and which arises from eigenvector

$^\prime \equiv {\rm \pi}_y$FP3, whose diagonal is reversed and which arises from eigenvector ![]() ${\rm \pi} _y e_1$. The amplitudes of

${\rm \pi} _y e_1$. The amplitudes of ![]() $e_1$ and

$e_1$ and ![]() ${\rm \pi} _y e_1$ are represented in the model (3.3) by variables

${\rm \pi} _y e_1$ are represented in the model (3.3) by variables ![]() $p$ and

$p$ and ![]() $q$:

$q$:

The eigenvector ![]() $e_2$ of FP2 leading to state FP5 is shown in figure 4(e). Eigenvector

$e_2$ of FP2 leading to state FP5 is shown in figure 4(e). Eigenvector ![]() $e_2$ turns out to be identical to the equal superposition of

$e_2$ turns out to be identical to the equal superposition of ![]() $e_1$ and

$e_1$ and ![]() ${\rm \pi} _y e_1$, as shown in figure 4(c). This is a manifestation of the fact that, in the model (3.3), the rectangular solutions (3.4c) and (3.4d) contain equal amplitudes of

${\rm \pi} _y e_1$, as shown in figure 4(c). This is a manifestation of the fact that, in the model (3.3), the rectangular solutions (3.4c) and (3.4d) contain equal amplitudes of ![]() $p$ and

$p$ and ![]() $q$. The shifted eigenvector

$q$. The shifted eigenvector ![]() $\tau (L_y/4,-L_z/4)e_2$ leads to

$\tau (L_y/4,-L_z/4)e_2$ leads to ![]() $\textrm {FP}5^{\prime } \equiv \tau (L_y/4,-L_z/4)\textrm {FP}5$; its superposition with

$\textrm {FP}5^{\prime } \equiv \tau (L_y/4,-L_z/4)\textrm {FP}5$; its superposition with ![]() $e_2$ produces

$e_2$ produces ![]() $e_1$. Indeed, in the model (3.3), equal superpositions of rectangular solutions of types (3.4c) and (3.4d) produce the diagonal solutions of types (3.4a) and (3.4b). (Figures 4(d) and 4(h) are also eigenvectors of FP2, identical to figures 4(f) and 4(b), respectively.) In figure 4, the eigenvectors have been approximated by subtracting FP2 from FP3 and from FP5 just beyond the bifurcation point (

$e_1$. Indeed, in the model (3.3), equal superpositions of rectangular solutions of types (3.4c) and (3.4d) produce the diagonal solutions of types (3.4a) and (3.4b). (Figures 4(d) and 4(h) are also eigenvectors of FP2, identical to figures 4(f) and 4(b), respectively.) In figure 4, the eigenvectors have been approximated by subtracting FP2 from FP3 and from FP5 just beyond the bifurcation point (![]() $Ra=6058.5$ for FP2 and

$Ra=6058.5$ for FP2 and ![]() $Ra=6056$ for FP3 and FP5). This selects the appropriate choices out of the multitude of eigenvectors of the highly symmetric FP2.

$Ra=6056$ for FP3 and FP5). This selects the appropriate choices out of the multitude of eigenvectors of the highly symmetric FP2.

Just as solutions (3.4c) and (3.4d) are not related to solutions (3.4a) or (3.4b) by any symmetry operation, FP5 cannot be produced by a symmetry transformation from FP3. In addition, figure 2(a) makes it clear that branches FP3 and FP5 behave differently, with a different global temperature norm and different saddle-node bifurcations.

We turn now to the simultaneous bifurcations of FP4 and FP5 from FP1 at ![]() $Ra = 6131$. The symmetries of FP1 are generated by reflection and translation in

$Ra = 6131$. The symmetries of FP1 are generated by reflection and translation in ![]() $y$ together with reflection in

$y$ together with reflection in ![]() $(x,z)$ and fourfold translation in

$(x,z)$ and fourfold translation in ![]() $z$, i.e.

$z$, i.e. ![]() $[O(2)]_y \times [D_4]_{xz}$. We again compute the eigenvectors of FP1 responsible for these two bifurcations. Taking symmetry transformations and superpositions, we obtain the eigenvector responsible for FP5 (FP4) as the equal superposition of the eigenvector responsible for FP4 (FP5) with a symmetry-transformed version of it. Interestingly, the eigenvectors responsible for the simultaneous bifurcation from

$[O(2)]_y \times [D_4]_{xz}$. We again compute the eigenvectors of FP1 responsible for these two bifurcations. Taking symmetry transformations and superpositions, we obtain the eigenvector responsible for FP5 (FP4) as the equal superposition of the eigenvector responsible for FP4 (FP5) with a symmetry-transformed version of it. Interestingly, the eigenvectors responsible for the simultaneous bifurcation from ![]() $\textrm {FP}1\rightarrow (\textrm {FP}4, \textrm {FP}5)$ at

$\textrm {FP}1\rightarrow (\textrm {FP}4, \textrm {FP}5)$ at ![]() $Ra=6131$ are very similar to those responsible for the simultaneous bifurcation from

$Ra=6131$ are very similar to those responsible for the simultaneous bifurcation from ![]() $\textrm {FP}2\rightarrow (\textrm {FP}3, \textrm {FP}5)$ at

$\textrm {FP}2\rightarrow (\textrm {FP}3, \textrm {FP}5)$ at ![]() $Ra=6058.5$. This can be explained as follows. The two simultaneous bifurcations occur at Rayleigh numbers which are close to each other and to

$Ra=6058.5$. This can be explained as follows. The two simultaneous bifurcations occur at Rayleigh numbers which are close to each other and to ![]() $Ra=6056$, at which FP2 is formed via a supercritical circle pitchfork bifurcation from FP1. Fixed point FP2 inherits the spectrum of FP1, with the exception of the double eigenvalue responsible for the circle pitchfork. (Just above

$Ra=6056$, at which FP2 is formed via a supercritical circle pitchfork bifurcation from FP1. Fixed point FP2 inherits the spectrum of FP1, with the exception of the double eigenvalue responsible for the circle pitchfork. (Just above ![]() $Ra=6056$, this double eigenvalue becomes positive for FP1, whereas it splits into a zero and negative eigenvalue for FP2.) The other eigenvectors and eigenvalues of FP2 at

$Ra=6056$, this double eigenvalue becomes positive for FP1, whereas it splits into a zero and negative eigenvalue for FP2.) The other eigenvectors and eigenvalues of FP2 at ![]() $Ra=6058.5$ are close to those of FP1 at

$Ra=6058.5$ are close to those of FP1 at ![]() $Ra=6131$, including those shown in figure 4 which cause the simultaneous bifurcations. We do not show the eigenvectors of FP1 to avoid repetition.

$Ra=6131$, including those shown in figure 4 which cause the simultaneous bifurcations. We do not show the eigenvectors of FP1 to avoid repetition.

It has been known since the mid-1980s (Swift Reference Swift1985) that ![]() $D_4$ symmetry leads to the simultaneous creation of non-symmetry-related branches. This has been applied to a number of situations, such as the simultaneous creation of standing and traveling waves (Knobloch Reference Knobloch1986; Borońska & Tuckerman Reference Borońska and Tuckerman2006; Reetz et al. Reference Reetz, Subramanian and Schneider2020). The application most relevant here is that of counter-rotating Taylor–Couette flow, in which spirals were first described in the classic paper by Taylor (Reference Taylor1923). The superposition of spirals of opposite helicity leads to a state called ribbons, much as the superposition of diagonal states produces the rectangular states in the current study. Exceptionally, ribbons were first predicted mathematically (Demay & Iooss Reference Demay and Iooss1984; Chossat & Iooss Reference Chossat and Iooss1994), setting off a quest to observe them experimentally, which was finally achieved by Tagg et al. (Reference Tagg, Edwards, Swinney and Marcus1989).

$D_4$ symmetry leads to the simultaneous creation of non-symmetry-related branches. This has been applied to a number of situations, such as the simultaneous creation of standing and traveling waves (Knobloch Reference Knobloch1986; Borońska & Tuckerman Reference Borońska and Tuckerman2006; Reetz et al. Reference Reetz, Subramanian and Schneider2020). The application most relevant here is that of counter-rotating Taylor–Couette flow, in which spirals were first described in the classic paper by Taylor (Reference Taylor1923). The superposition of spirals of opposite helicity leads to a state called ribbons, much as the superposition of diagonal states produces the rectangular states in the current study. Exceptionally, ribbons were first predicted mathematically (Demay & Iooss Reference Demay and Iooss1984; Chossat & Iooss Reference Chossat and Iooss1994), setting off a quest to observe them experimentally, which was finally achieved by Tagg et al. (Reference Tagg, Edwards, Swinney and Marcus1989).

4. Periodic orbits

In this section, we explore four periodic orbits, PO1–PO4. Periodic orbits PO1–PO3 are created by a sequence of local bifurcations (i.e. bifurcations associated with a change in the real part of one or more eigenvalues/Floquet exponents): ![]() $\textrm {FP}3\rightarrow \textrm {PO}1\rightarrow \textrm {PO}2\rightarrow \textrm {PO}3$. PO1 and PO2 disappear in a global homoclinic and heteroclinic bifurcation, respectively, whereas the termination of PO3 is not discussed in this work. Periodic orbit PO4 bifurcates from and terminates on FP6 via Hopf bifurcations. The bifurcation diagram of figure 5(a) shows the six equilibria discussed in § 3 and the four periodic orbits to be discussed, whereas the periods of the limit cycles are shown in figure 5(b).

$\textrm {FP}3\rightarrow \textrm {PO}1\rightarrow \textrm {PO}2\rightarrow \textrm {PO}3$. PO1 and PO2 disappear in a global homoclinic and heteroclinic bifurcation, respectively, whereas the termination of PO3 is not discussed in this work. Periodic orbit PO4 bifurcates from and terminates on FP6 via Hopf bifurcations. The bifurcation diagram of figure 5(a) shows the six equilibria discussed in § 3 and the four periodic orbits to be discussed, whereas the periods of the limit cycles are shown in figure 5(b).

Figure 5. (a) Bifurcation diagram of fixed points (FPs) and periodic orbits (POs) and (b) periods of four periodic orbits in domain ![]() $[L_x, L_y, L_z] = [1, 8, 9]$. In (a), for each periodic orbit, we show two curves, the maximum and minimum of

$[L_x, L_y, L_z] = [1, 8, 9]$. In (a), for each periodic orbit, we show two curves, the maximum and minimum of ![]() $\lvert \lvert \theta \lvert \lvert _2$ along an orbit. Periodic orbit PO1 appears via a Hopf bifurcation from FP3 at

$\lvert \lvert \theta \lvert \lvert _2$ along an orbit. Periodic orbit PO1 appears via a Hopf bifurcation from FP3 at ![]() $Ra=6140$ (marked by a cyan cross) and undergoes a period-doubling bifurcation at

$Ra=6140$ (marked by a cyan cross) and undergoes a period-doubling bifurcation at ![]() $Ra=6154.7$ giving rise to PO2. Periodic orbit PO1 then undergoes a saddle-node bifurcation at

$Ra=6154.7$ giving rise to PO2. Periodic orbit PO1 then undergoes a saddle-node bifurcation at ![]() $Ra=6157.97$ and disappears by meeting FP4 in a homoclinic bifurcation at

$Ra=6157.97$ and disappears by meeting FP4 in a homoclinic bifurcation at ![]() $Ra_{hom}=6151.97$ at which its period diverges; see (b). Periodic orbit PO2 loses stability at

$Ra_{hom}=6151.97$ at which its period diverges; see (b). Periodic orbit PO2 loses stability at ![]() $Ra = 6173.8$ where PO3 is created via a supercritical pitchfork bifurcation. The stability of PO2 changes multiple times along the branch for

$Ra = 6173.8$ where PO3 is created via a supercritical pitchfork bifurcation. The stability of PO2 changes multiple times along the branch for ![]() $6235< Ra<6255$, see details in figure 12. Periodic orbit PO2 then undergoes two closely spaced saddle-node bifurcations (at

$6235< Ra<6255$, see details in figure 12. Periodic orbit PO2 then undergoes two closely spaced saddle-node bifurcations (at ![]() $Ra=6276$ and

$Ra=6276$ and ![]() $6273.6$; see panel b) before terminating by meeting two symmetrically related versions of FP2 in a heteroclinic bifurcation at

$6273.6$; see panel b) before terminating by meeting two symmetrically related versions of FP2 in a heteroclinic bifurcation at ![]() $Ra_{het}=6277.95$, at which its period diverges. Periodic orbit PO3 is continued until

$Ra_{het}=6277.95$, at which its period diverges. Periodic orbit PO3 is continued until ![]() $Ra=6407.3$ (the range

$Ra=6407.3$ (the range ![]() $6340< Ra<6407.3$ is not shown) and its period remains approximately constant. The apparent lack of smoothness in the curves representing PO2 and PO3 (in panel a around

$6340< Ra<6407.3$ is not shown) and its period remains approximately constant. The apparent lack of smoothness in the curves representing PO2 and PO3 (in panel a around ![]() $Ra=6250$) corresponds to the overtaking of one temporal maximum or minimum of

$Ra=6250$) corresponds to the overtaking of one temporal maximum or minimum of ![]() $\lvert \lvert \theta \lvert \lvert _2$ by another as

$\lvert \lvert \theta \lvert \lvert _2$ by another as ![]() $Ra$ is varied. Periodic orbit PO4 bifurcates from and terminates on FP6 at

$Ra$ is varied. Periodic orbit PO4 bifurcates from and terminates on FP6 at ![]() $Ra=6257.6$ and

$Ra=6257.6$ and ![]() $Ra=6328.8$, and it is stable within

$Ra=6328.8$, and it is stable within ![]() $6257.6< Ra<6278$. In (a), solid and dashed curves signify stable and unstable states respectively, and the curves representing periodic orbits are slightly thicker than those of fixed points. The same colour code is used in (a,b). A schematic bifurcation diagram is shown in figure 15. Many other branches of equilibria and periodic orbits exist, which we have not followed nor shown on this diagram.

$6257.6< Ra<6278$. In (a), solid and dashed curves signify stable and unstable states respectively, and the curves representing periodic orbits are slightly thicker than those of fixed points. The same colour code is used in (a,b). A schematic bifurcation diagram is shown in figure 15. Many other branches of equilibria and periodic orbits exist, which we have not followed nor shown on this diagram.

4.1. First periodic orbit (PO1)

4.1.1. Creation of PO1: Hopf bifurcation

Produced by a subcritical pitchfork bifurcation from FP2, FP3 is unstable at onset, but is stabilised by a saddle-node bifurcation at ![]() $Ra = 6008.5$ and then loses stability again at

$Ra = 6008.5$ and then loses stability again at ![]() $Ra = 6140$ via a supercritical Hopf bifurcation that produces a periodic orbit PO1. PO1 inherits all of the spatial symmetries of FP3:

$Ra = 6140$ via a supercritical Hopf bifurcation that produces a periodic orbit PO1. PO1 inherits all of the spatial symmetries of FP3: ![]() $\langle {{\rm \pi} _y{\rm \pi} _{xz}, \tau (L_y/4,-L_z/4)} \rangle \sim D_4$ and, hence, no additional spatiotemporal symmetries are present. The S-shaped green curve in figure 5(a) contains the maximum (PO1

$\langle {{\rm \pi} _y{\rm \pi} _{xz}, \tau (L_y/4,-L_z/4)} \rangle \sim D_4$ and, hence, no additional spatiotemporal symmetries are present. The S-shaped green curve in figure 5(a) contains the maximum (PO1![]() $_{max}$, above the cyan curve of FP3) and minimum (PO1

$_{max}$, above the cyan curve of FP3) and minimum (PO1![]() $_{min}$, below the cyan curve) values of

$_{min}$, below the cyan curve) values of ![]() $\lvert \lvert \theta \lvert \lvert _2$ over the period of each PO1 state. The period (

$\lvert \lvert \theta \lvert \lvert _2$ over the period of each PO1 state. The period (![]() $T$) of PO1 increases smoothly before the saddle-node bifurcation at

$T$) of PO1 increases smoothly before the saddle-node bifurcation at ![]() $Ra = 6157.97$. Prior to this, PO1 loses stability by undergoing a period-doubling bifurcation at

$Ra = 6157.97$. Prior to this, PO1 loses stability by undergoing a period-doubling bifurcation at ![]() $Ra=6154.7$ to PO2, which is discussed in § 4.2.1. The saddle-node bifurcation can be seen in both the maximum and minimum dashed green curves of figure 5(a) and leads to what we call the lower branch (because of its lower value of

$Ra=6154.7$ to PO2, which is discussed in § 4.2.1. The saddle-node bifurcation can be seen in both the maximum and minimum dashed green curves of figure 5(a) and leads to what we call the lower branch (because of its lower value of ![]() $\lvert \lvert \theta \lvert \lvert _2$).

$\lvert \lvert \theta \lvert \lvert _2$).

By using the multi-shooting method with two to five shots, we have been able to continue the lower PO1 branch down in Rayleigh number to ![]() $Ra=6152.2041$, where the period of PO1 is very long:

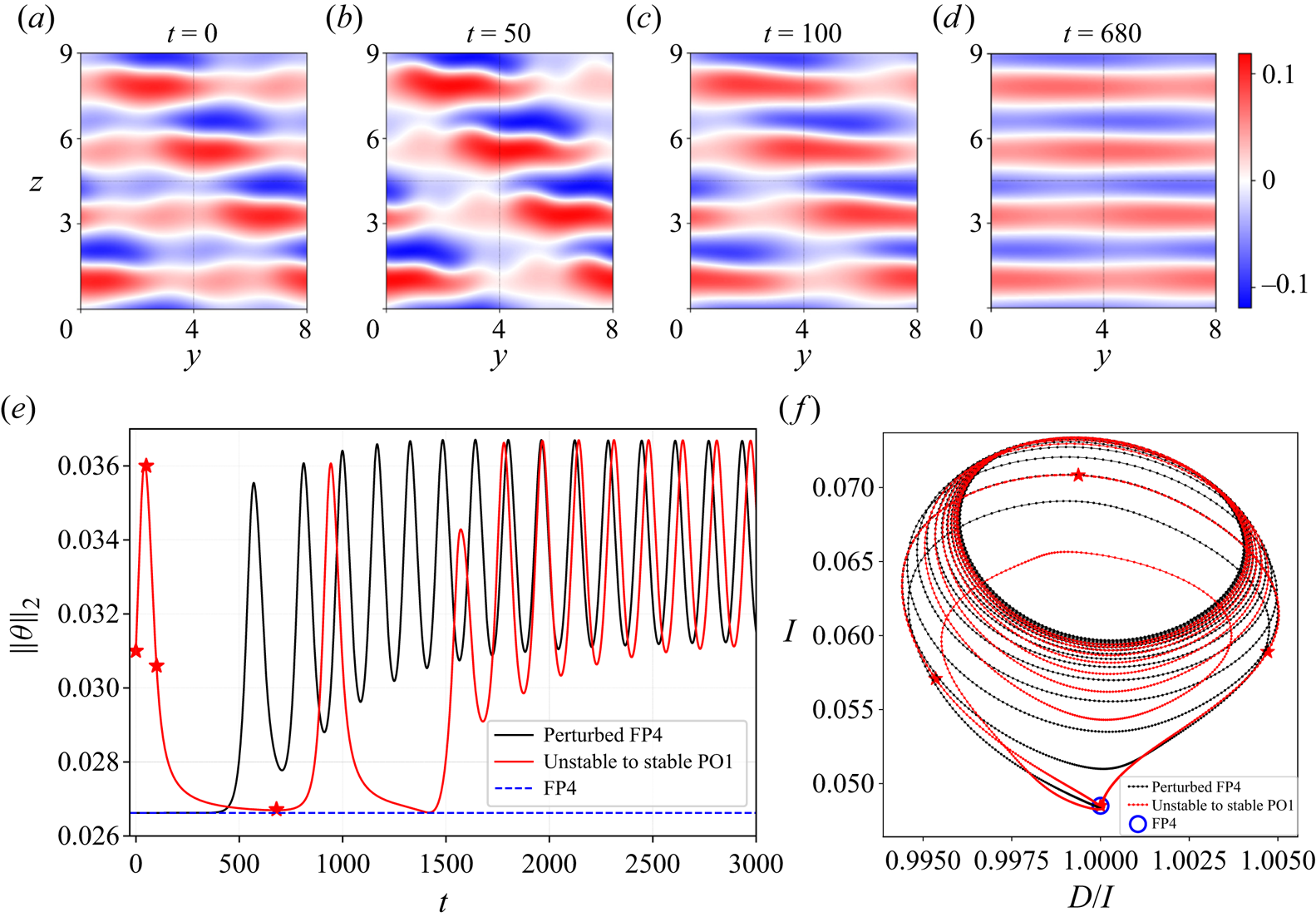

$Ra=6152.2041$, where the period of PO1 is very long: ![]() $T=955.4$ time units. We will show in § 4.1.2 that PO1 disappears via a homoclinic bifurcation, at which its period is infinite. Figures 6(a)–6(d) show snapshots of PO1 at

$T=955.4$ time units. We will show in § 4.1.2 that PO1 disappears via a homoclinic bifurcation, at which its period is infinite. Figures 6(a)–6(d) show snapshots of PO1 at ![]() $Ra = 6152.249$, on the lower branch. Among these snapshots, figures 6(a) and 6(b) capture the thinning and thickening of the rolls along the diagonal, with local waviness along the edge of the rolls. The waviness becomes weaker in figure 6(c) and finally, in figure 6(d) the edges are smoother and the roll widths almost uniform. All of the states in the cycle have a definite diagonal orientation. This implies that there exists another version of PO1 with the opposite diagonal orientation. The times at which these snapshots are taken are marked by stars in figures 6(e) and 6(f).

$Ra = 6152.249$, on the lower branch. Among these snapshots, figures 6(a) and 6(b) capture the thinning and thickening of the rolls along the diagonal, with local waviness along the edge of the rolls. The waviness becomes weaker in figure 6(c) and finally, in figure 6(d) the edges are smoother and the roll widths almost uniform. All of the states in the cycle have a definite diagonal orientation. This implies that there exists another version of PO1 with the opposite diagonal orientation. The times at which these snapshots are taken are marked by stars in figures 6(e) and 6(f).

Figure 6. (a–d) The dynamics of PO1 (visualised via the temperature field on the ![]() $y$–

$y$–![]() $z$ plane at

$z$ plane at ![]() $x=0$) on the unstable lower branch at

$x=0$) on the unstable lower branch at ![]() $Ra = 6152.249$ (

$Ra = 6152.249$ (![]() $Ra_{hom} = 6151.97$). Snapshot (d) converges to FP4 when used as an initial estimate for Newton solving. (e) Time series from DNS at

$Ra_{hom} = 6151.97$). Snapshot (d) converges to FP4 when used as an initial estimate for Newton solving. (e) Time series from DNS at ![]() $Ra =6152.249$ (

$Ra =6152.249$ (![]() $T=900$), initialised by the unstable PO1 shown in (a) (red curve) and by FP4 with a small perturbation (black). The trajectory initialised by the unstable PO1 spends a long time near FP4 (

$T=900$), initialised by the unstable PO1 shown in (a) (red curve) and by FP4 with a small perturbation (black). The trajectory initialised by the unstable PO1 spends a long time near FP4 (![]() $250< t<800$). Both simulations converge to the stable PO1 branch (

$250< t<800$). Both simulations converge to the stable PO1 branch (![]() $t>2500$) at this Rayleigh number. (f) Phase portrait illustrating the same data set as in (e). The plot shows the thermal energy input (

$t>2500$) at this Rayleigh number. (f) Phase portrait illustrating the same data set as in (e). The plot shows the thermal energy input (![]() $I$) vs the viscous dissipation over energy input (

$I$) vs the viscous dissipation over energy input (![]() $D/I$). Fixed point FP4 (hollow blue circle) is located on the vertical line

$D/I$). Fixed point FP4 (hollow blue circle) is located on the vertical line ![]() $D/I=1$, where energy dissipation and input are equal. The four red stars in (e,f) indicate the moments at which the snapshots (a–d) are taken. The same colour code is used in (e,f).

$D/I=1$, where energy dissipation and input are equal. The four red stars in (e,f) indicate the moments at which the snapshots (a–d) are taken. The same colour code is used in (e,f).

Figure 6(e) shows time series initialised with this unstable PO1 and also with a slightly perturbed FP4, at ![]() $Ra=6152.249$. Both of these runs eventually converge to another state: the stable upper branch of PO1, whose period

$Ra=6152.249$. Both of these runs eventually converge to another state: the stable upper branch of PO1, whose period ![]() $T = 161$ is much shorter than the period

$T = 161$ is much shorter than the period ![]() $T=900$ of the lower branch PO1. For

$T=900$ of the lower branch PO1. For ![]() $t< 1000$, the red curve remains close to FP4 during a large portion of the period. Figure 6(d) corresponds to the fourth star of 6(e), indicating via this projection that 6(d) is long-lived and very close to FP4. Indeed, we used figure 6(d) as the initial estimate for Newton's method to converge to FP4 at

$t< 1000$, the red curve remains close to FP4 during a large portion of the period. Figure 6(d) corresponds to the fourth star of 6(e), indicating via this projection that 6(d) is long-lived and very close to FP4. Indeed, we used figure 6(d) as the initial estimate for Newton's method to converge to FP4 at ![]() $Ra=6152.249$. However, figure 6(c), which only shows a transient at

$Ra=6152.249$. However, figure 6(c), which only shows a transient at ![]() $Ra=6152.249$, resembles figure 2(e), which shows the converged FP4 at

$Ra=6152.249$, resembles figure 2(e), which shows the converged FP4 at ![]() $Ra=6281$. We see from this that the diagonal orientation of FP4 becomes more prominent at higher Rayleigh numbers. Figure 6(f) shows a phase portrait from the same simulation as 6(e), using the thermal energy input

$Ra=6281$. We see from this that the diagonal orientation of FP4 becomes more prominent at higher Rayleigh numbers. Figure 6(f) shows a phase portrait from the same simulation as 6(e), using the thermal energy input ![]() $I$ and viscous dissipation

$I$ and viscous dissipation ![]() $D$. There, FP4 is indicated as the hollow blue circle with

$D$. There, FP4 is indicated as the hollow blue circle with ![]() $D/I=1$, showing that energy dissipation and input are equal. Near FP4, the dotted red curve looks continuous; this is due to the clustering of points near FP4.

$D/I=1$, showing that energy dissipation and input are equal. Near FP4, the dotted red curve looks continuous; this is due to the clustering of points near FP4.

4.1.2. Termination of PO1: homoclinic bifurcation

The close approach to FP4 implies that PO1 is close to a homoclinic cycle. We have verified that this closest approach is always to the same version of FP4 and not to another symmetry-related version. Thus, PO1 approaches a homoclinic, and not a heteroclinic cycle. A homoclinic cycle approaches a fixed point along one of its stable directions and escapes from it along one of its unstable directions. For this reason, we compute the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of FP4. Figure 7(a) shows the leading eigenvalues that we have computed at ![]() $Ra = 6152.249$, close to the global bifurcation point. The seven leading eigenvalues, all real, are

$Ra = 6152.249$, close to the global bifurcation point. The seven leading eigenvalues, all real, are ![]() $[\lambda _1, \lambda _2, \lambda _3, \lambda _4, \lambda _5, \lambda _6, \lambda _7] = [0.0212, 0.0208, 0.0026, 0, 0, -0.00017, -0.0034]$. We have set any eigenvalue whose absolute value is less than

$[\lambda _1, \lambda _2, \lambda _3, \lambda _4, \lambda _5, \lambda _6, \lambda _7] = [0.0212, 0.0208, 0.0026, 0, 0, -0.00017, -0.0034]$. We have set any eigenvalue whose absolute value is less than ![]() $10^{-7}$ to zero. Figure 7(a) shows other eigenvalues with smaller real parts as well and some of the eigenvalues are too close together to be distinguished. Certain eigenvalues of special significance are highlighted by coloured circles and their corresponding eigenvectors are shown in figures 7(c)–7(f).

$10^{-7}$ to zero. Figure 7(a) shows other eigenvalues with smaller real parts as well and some of the eigenvalues are too close together to be distinguished. Certain eigenvalues of special significance are highlighted by coloured circles and their corresponding eigenvectors are shown in figures 7(c)–7(f).

Figure 7. (a) Leading eigenvalues at ![]() $Ra=6152.249$ of FP4:

$Ra=6152.249$ of FP4: ![]() $[\lambda _1, \lambda _2, \lambda _3, \lambda _4, \lambda _5, \lambda _6, \lambda _7] = [0.0212, 0.0208, 0.0026, 0, 0, -0.00017, -0.0034]$. Eigenvalues

$[\lambda _1, \lambda _2, \lambda _3, \lambda _4, \lambda _5, \lambda _6, \lambda _7] = [0.0212, 0.0208, 0.0026, 0, 0, -0.00017, -0.0034]$. Eigenvalues ![]() $\lambda _2$ (escaping, red),

$\lambda _2$ (escaping, red), ![]() $\lambda _{4,5}$ (neutral, green) and

$\lambda _{4,5}$ (neutral, green) and ![]() $\lambda _7$ (approaching, blue) are marked in colour. (b) The

$\lambda _7$ (approaching, blue) are marked in colour. (b) The ![]() $L_2$-distance between each instantaneous flow field of PO1 and FP4 at

$L_2$-distance between each instantaneous flow field of PO1 and FP4 at ![]() $Ra=6152.249$, close to

$Ra=6152.249$, close to ![]() $Ra_{hom}=6151.97$. The evolution of PO1 (black curve) is exponential most of the time, with the escape from (red line) and approach to (blue line) FP4 governed by

$Ra_{hom}=6151.97$. The evolution of PO1 (black curve) is exponential most of the time, with the escape from (red line) and approach to (blue line) FP4 governed by ![]() $\lambda _2$ and

$\lambda _2$ and ![]() $\lambda _7$. (c–f) Four leading eigenmodes of FP4 at

$\lambda _7$. (c–f) Four leading eigenmodes of FP4 at ![]() $Ra = 6152.249$, visualised via the temperature field on the

$Ra = 6152.249$, visualised via the temperature field on the ![]() $y$–

$y$–![]() $z$ plane at

$z$ plane at ![]() $x=0$:

$x=0$: ![]() $e_2$,

$e_2$, ![]() $e_{4}$,

$e_{4}$, ![]() $e_{5}$ and

$e_{5}$ and ![]() $e_7$. The same colour bar is used in all plots.

$e_7$. The same colour bar is used in all plots.

The eigenvectors can be interpreted by considering FP4 and PO1, as depicted in figures 6(a)–6(d). There are two neutral directions, due to the continuous translation symmetry in the periodic directions. Eigenvalue ![]() $\lambda _4$ is zero and the corresponding eigenvector

$\lambda _4$ is zero and the corresponding eigenvector ![]() $e_4$, depicted in figure 7(d), is the neutral mode associated with

$e_4$, depicted in figure 7(d), is the neutral mode associated with ![]() $z$-translation (i.e. the

$z$-translation (i.e. the ![]() $z$ derivative) of the roll-like FP4, very close to a z-translated version of figure 6(d). There must also be a marginal eigenvector corresponding to

$z$ derivative) of the roll-like FP4, very close to a z-translated version of figure 6(d). There must also be a marginal eigenvector corresponding to ![]() $y$-translation and indeed,

$y$-translation and indeed, ![]() $\lambda _5=0$ and we have verified numerically that

$\lambda _5=0$ and we have verified numerically that ![]() $e_5$, depicted in figure 7(e), is the

$e_5$, depicted in figure 7(e), is the ![]() $y$ derivative of FP4. This is not immediately obvious, but note that for

$y$ derivative of FP4. This is not immediately obvious, but note that for ![]() $z$ constant, the

$z$ constant, the ![]() $y$ derivative of FP4 oscillates in sign and its maxima and minima are located along a diagonal. The green circle in figure 7(a) contains

$y$ derivative of FP4 oscillates in sign and its maxima and minima are located along a diagonal. The green circle in figure 7(a) contains ![]() $\lambda _4$ and

$\lambda _4$ and ![]() $\lambda _5$ (but also

$\lambda _5$ (but also ![]() $\lambda _6$, whose decay rate is very small).

$\lambda _6$, whose decay rate is very small).

The other two eigenvectors shown in figures 7(c) and 7(f) are responsible for the approach to and escape from FP4. We have determined which eigenvalues are associated with approach and escape by comparing them with the observed approach and escape rates, and also by subtracting FP4 from the instantaneous flow fields and comparing the result to the eigenvectors. For the escaping dynamics of PO1 from FP4, the quantity (![]() $||\boldsymbol {x}(t) - \textrm {FP4}||_2$) increases exponentially at rate

$||\boldsymbol {x}(t) - \textrm {FP4}||_2$) increases exponentially at rate ![]() $\lambda _2=0.0208$. The corresponding eigenvector

$\lambda _2=0.0208$. The corresponding eigenvector ![]() $e_2$ is shown in figure 7(c) and can be viewed as corresponding to widening and narrowing of the rolls. The approaching dynamics is characterised by

$e_2$ is shown in figure 7(c) and can be viewed as corresponding to widening and narrowing of the rolls. The approaching dynamics is characterised by ![]() $\lambda _7=-0.0034$. The corresponding eigenvector

$\lambda _7=-0.0034$. The corresponding eigenvector ![]() $e_7$, shown in figure 7(f), can be viewed as corresponding to translation in

$e_7$, shown in figure 7(f), can be viewed as corresponding to translation in ![]() $y$. The portion of PO1 escaping FP4 along

$y$. The portion of PO1 escaping FP4 along ![]() $e_2$ has been fit to the red line in figure 7(b). Although the rate of escape matches

$e_2$ has been fit to the red line in figure 7(b). Although the rate of escape matches ![]() $\lambda _2$ closely, the approach rate only fits

$\lambda _2$ closely, the approach rate only fits ![]() $\lambda _7$ over a short range of time (blue line). In figure 7(a), the red circle contains

$\lambda _7$ over a short range of time (blue line). In figure 7(a), the red circle contains ![]() $\lambda _2$ (but also

$\lambda _2$ (but also ![]() $\lambda _1$, which is very close to

$\lambda _1$, which is very close to ![]() $\lambda _2$), and the blue circle encloses

$\lambda _2$), and the blue circle encloses ![]() $\lambda _7$.

$\lambda _7$.

The eigendirection ![]() $e_7$ along which PO1 approaches FP4 is not the leading stable (least negative) one, as would be usual for a homoclinic orbit. This is because PO1 exists in the invariant symmetry-restricted subspace

$e_7$ along which PO1 approaches FP4 is not the leading stable (least negative) one, as would be usual for a homoclinic orbit. This is because PO1 exists in the invariant symmetry-restricted subspace ![]() $\langle {\tau (L_y/4,-L_z/4)} \rangle$, to which

$\langle {\tau (L_y/4,-L_z/4)} \rangle$, to which ![]() $e_7$ also belongs. In contrast,

$e_7$ also belongs. In contrast, ![]() $e_6$ (not shown), whose eigenvalue

$e_6$ (not shown), whose eigenvalue ![]() $\lambda_6$ is slightly less negative, has the opposite symmetry

$\lambda_6$ is slightly less negative, has the opposite symmetry ![]() $\langle {\tau (L_y/4,L_z/4)} \rangle$. Note also that near-homoclinic orbits for which the rate of escape exceeds the rate of approach (i.e. here